Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

One Hundred Years of Swissness

A renovation of a 1912 chalet so beautiful it spawns an interior design company

In 2012, Virginie Confino, a photo editor, and her science journalist husband Bastien fall in love with a 100-year-old chalet in Val-d’Illiez, near the Portes du Soleil ski resort in the Swiss Alps. Without any prior knowledge in building or renovation, the couple abolishes their resolution not to entrap themselves in any kind of serious remodeling project and deconstructs the faded chalet. The result was so beautiful, it propelled Virginie into the new adventure of launching her own interior design business, Gris Souris.

The story in her own words...

We were looking for a holiday home for our family of four. We visited some chalets, but none of them felt right for us. Until we found this one. We fell in love with the balcony at first sight; its whimsical railing looks like lace.

Inside, the chalet was old and untouched since the 1960s. The walls lacked any sort of insulation, the house had no heat and a ladder in the living room was the only way to reach the upstairs, no stairs.

Intention out the window

Right away, we had a vision for how we would transform this chalet. Although, when we first began searching for a property, we had no intention to throw ourselves head-first into a renovation project. Our limited budget meant that we had to do almost all of the work ourselves. What’s more, neither of us had any experience even close to remodeling or construction — me a freelance photo editor for the press and my husband a science journalist. But Bastien has always believed, “Anything is possible.” And we did it!

My husband learned a lot from books, the Internet and YouTube videos, and I joined him at the chalet two days a week for a year and a half. We required professional help with the masonry in the entrance, because the rain was coming in, with the terrace outside, and with the heating and plumbing.

We virtually gutted the inside of the house. We just wanted to keep some of the old elements, such as the old wood floors, stairs and doors. Once we finished insulating the house from the bottom to the roof, we put the old wood back on the walls. We used a lot of wood on the inside, old wood, and slate for the bathroom floors.

1912 on the outside, Swiss modern on the inside

The chalet is a mix of old and modern. Because we have a big entrance, I wanted to do something special there. We chose a transparent door that gives view to the log wall, which is a decoy we created by cutting about 4000 logs of wood into five-centimeter pieces, 15 centimeters at the top. We dried the logs and fixed them together. The wall alone took ten days of work.

We remodeled the kitchen simply by changing the cabinet doors and painting the walls. Almost all of the furniture is from IKEA. We didn’t want to furnish the chalet with special pieces because we are renting it out when we are not using it.

Bastien built the dining room table himself, because we couldn’t find one that was three meters long and not too expensive. We painted the table top with chalkboard paint so we can write on it when we play games.

The dining chairs are old Tolix chairs that sat outside for a long time, which gave them the perfect rust-like patina for the chalet. Two Butterfly chairs and Tolomeo Artemide lights on the walls, not much else. We incorporated old sleds we found in the cellar into the decor.

Outside, we have a nice terrace with amazing mountain views of the Dents du Midi. We enjoy looking at this mountain range while we take a Swedish bath outside, even when it’s snowing.

Gris Souris

Chalet Le 1912 became my “business card.” Once the renovation was finished, friends started asking me for interior design advice and even wanted me to renovate their chalet. Soon, my new adventure began, and I created Gris Souris, my interior design company in Lausanne. △

Photos by Myriam Ramel Baechler / Lumière du jour

Quietly Technical

A conversation with Aether Apparel founders Palmer West and Jonah Smith about fashion, functionality and travel

Springboarding off a career in coproducing independent films (Requiem for a Dream, Religulous), world travelers and urban explorers Palmer West and Jonah Smith founded the clothing label Aether Apparel on their shared adventure spirit and passion for functional, modern design.

AM What inspired you to embark on this new endeavor of starting your own clothing brand?

JS Palmer and I had been working together in the film industry and had produced ten movies together over a ten-year period. We were growing tired of film and knew we wanted to do something else. Also, we were in our mid-thirties and were re-evaluating our priorities.

PW We liked working together, and we started looking for another business to start. We wanted a business that would interest us, and we set up parameters that fit our creative desires and supported a lifestyle we wanted to live.

JS As “weekend warriors,” we were tired of the clothing options we found available, and the idea of developing a clothing line resonated with us. There was nothing sophisticated enough that we could wear both out of town on the weekend and back at home in the city. We started looking around and we found a void in the marketplace—there was a big distinction between fashion and what you could find at REI.

“We found a void in the marketplace—there was a big distinction between fashion and what you could find at REI.”

PW When Jonah and I made movies, we said we strived to only make movies we would want to see on opening night. We’ve always wanted to be fans of what we do, and we’ve kept the same mantra—we build things that we will use. It helps us stay true to a singular vision. We build what we believe in.

“We’ve always wanted to be fans of what we do. We build things that we will use. It helps us stay true to a singular vision. We build what we believe in.”

AM What’s your idea of a great adventure?

PW We struggle with what most people think of as adventure. For us, adventure and travel also evoke city, not just the backcountry. Adventure in the city can also be awesome.

Adventure is stuck in a box. One destination. Being a citizen of the world requires flexibility. You’re not just one person, nor are we asking you to be one.

AM What’s your vision for the brand?

JS We are building something—an aspirational brand with imagery and travel. We’re not hippy crunchy and we’re not high fashion—we’re in between. Design and functionality is important to us, and we are trying to make a brand that’s authentic and real. We are in the space between those.

“For us, adventure and travel also evoke city, not just the backcountry.”

AM Who are you, and for whom do you design?

PW We represent the traveled individual—someone who is young at heart, with an adventurous spirit.

We use imagery to connect with people. We want people to see these images and think, “Where was that?” We want to reach out to people and have them experience the places we love.

AM Talk about your passion for exploration and discovery...

JS We want to go to new places, experience new things, and we support the adventurous spirit in others. We share our stories and images to inspire this spirit of adventure. We often talk to customers who ask for input or suggestions on trips they are planning or tell us we’ve inspired them to visit a location. This is our passion.

PW Functional design inspires us. We make clothing that is built for adventure but still looks good at home. You don’t have to have a separate wardrobe. Clothing can be beautiful but doesn’t reek of utilitarianism. It’s quietly technical.

“Clothing can be beautiful but doesn’t reek of utilitarianism. It’s quietly technical.”

AM How did your background in film prepare you for starting a clothing company?

JS We came into this business being consumers. We came with opinions and with personal needs for our wardrobe.

Being a film producer, you’re the contractor. You hire people, resolve problems and then produce and execute.

“We came into this business being consumers. We came with opinions and with personal needs for our wardrobe.”

PW Producing movies and making clothing is the same thing: There are hundreds of balls in the air. You have to come in on budget and on time. You have to come together and on point. The “production hat” is very similar. You need a clear vision and then deliver it.

“Producing movies and making clothing is the same thing—there are hundreds of balls in the air.”

The film industry is visually driven, and it was easy for us to tell our story. In fact, we want to tell the story... without making us the central character. Our goal is to be true to who we are and speak to this. We tell our story through imagery.

AM What makes a great design partnership? Describe your collaboration. What does each of you bring to the table?

PW We get this question a lot. We’ve worked together for twenty years, and what makes a great partnership is a similar vision and knowing that we are going to the same place.

JS We look at things completely differently, but we compliment each other. There’s a freshness in looking at someone else’s perspective. If you have enough faith and trust in each other’s viewpoint, you can get to the next level.

AM The architecture of the Aether Apparel locations is truly distinctive. What role does the design of your stores play in telling your story?

JS Our film background is two- or three-dimensional, and we wanted to build an interactive environment to display our product. We trusted that if we built our stores in a way that embraces industrial and modern, and if you like our stores, you will like our clothes.

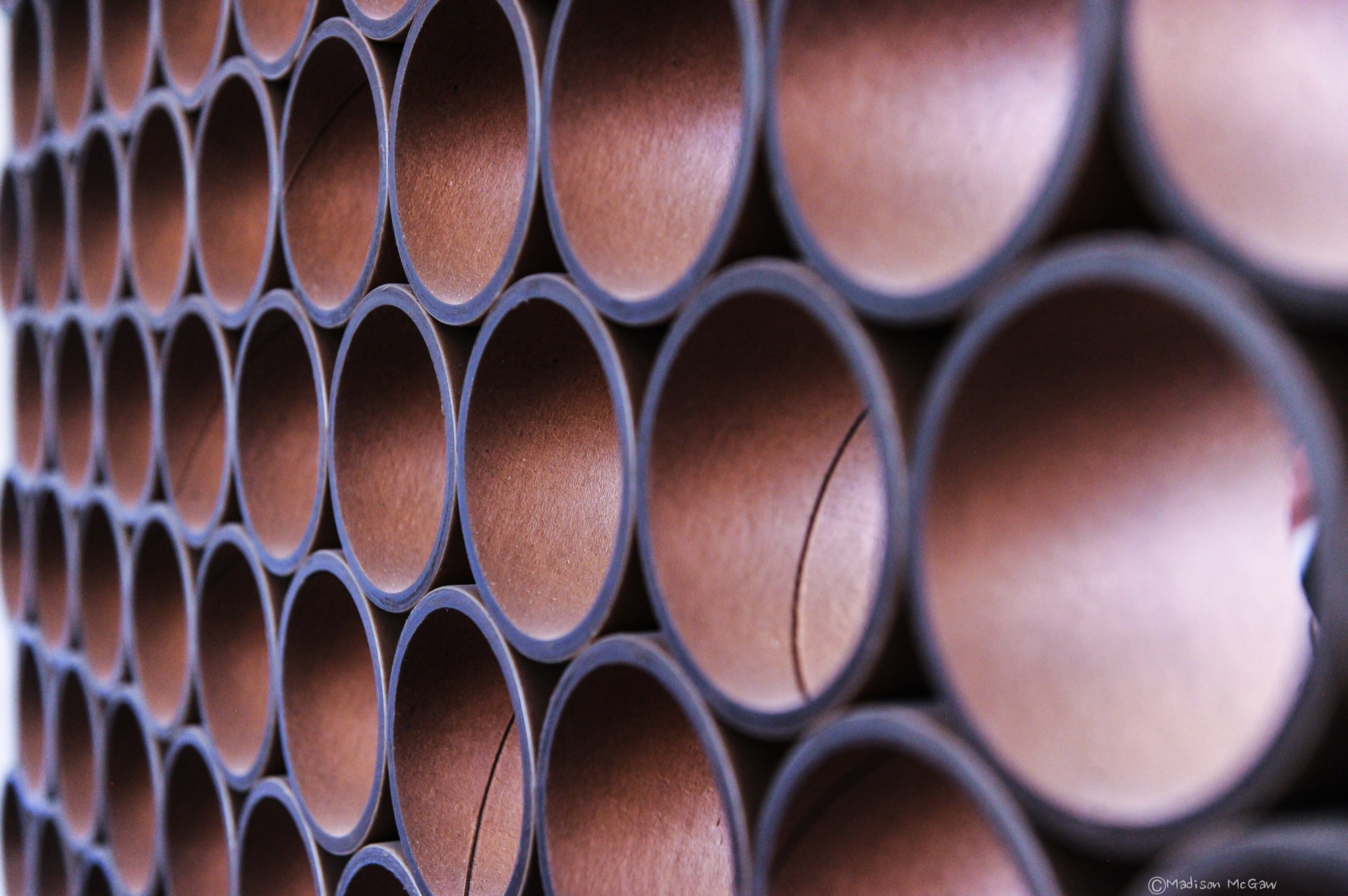

Our San Francisco location is made from three shipping containers stacked on top of one another and has a custom-designed dry cleaner’s conveyor belt running the height of the store to get clothes from storage on the third level.

Our other locations—New York, Los Angeles, and Aspen—have elements of the San Francisco location. However, the big component in these stores is large wood containers displaying product lit from within.

PW These large containers are modular boxes that are flexible, fluid spaces. Nothing is built into the brick and mortar of the location.

We were inspired by the idea of a nomadic life, when you would pack all your stuff and move. We like the flexibility to move things around, and besides, it hints at our spirit of adventure.

It’s about curation and presentation. You need to interact with our staff. It’s important that it feels authentic. △

“We were inspired by the idea of a nomadic life, when you would pack all your stuff and move.”

Aether Apparel lookbook Winter 2015/16 & Summer 2016

Photography by Ian Allen

Haus Z2 in Bayrischzell

The modern vacation home by Beer Bembé Dellinger reinterprets traditional Bavarian-alpine forms and materials

The large glass façade in the front and glass oriels on both sides of the house ensure a scenic view from the foot of the Wendelstein down to the valley from almost every room. The house's oblongness is inspired by the Alps and represents a reinterpretation of the characteristic traditional Bavarian barn. At the same time, the design concept addresses the site's narrow proportions.

The house's materials are also influenced by Bavarian-alpine traditions — mainly larchwood in form of tongue-and-groove boards for the façade and as shingles on the roof.

Lead architects were Felix Bembé (conception) and Michael Wondre (project leader and construction supervisor). △

Hideaway Cabin

Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta in Norway

Seemingly growing from the mountain, the impossibly small Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta shelters up to 21 people. The Norwegian firm Snøhetta creates architecture, landscapes, interiors and brand design. And in this case, incredibly small architecture with a big task.

Family shelter

The project was commissioned on family farmland by Osvald Bjelland, who is chairman and CEO of the global business advisory Xyntéo and founder of The Performance Theatre, a leadership think tank.

The challenge in designing the Åkrafjorden hunting lodge on a fjord, high in the mountains above the village of Etne in Hordaland, Norway, was indeed its small size in the face of its intended use: The mountain hut was to be maximum 35 square meters (ca. 377 square feet), with the capacity to shelter up to 21 people (the same number of beds as at the family's farmhouse down in the village). Plus, the off-grid structure with no running water needed to look like it had always been there.

Only accessible by foot or on horseback, the remote lodge’s setting is beautiful, isolated, beside a lake in the untouched Nordic wilderness of West Norway.

One important part of the design concept was to integrate the hut into the landscape. Thus, the small hut’s shape, orientation and materials are influenced by the terrain’s characteristic composition of grass, heather and glacial rocks. In winter, the cabin becomes another brown fleck — like the rocks — in mounds of snow.

Modern expression of ancient traditions

The structure consists of two curved steel beams, covered with a continuous layer of hand-cut logs of timber — a fusion of modern architectural expression and the style of traditional Norwegian mountain cabins. The roof, with its organic form, “grows” out of the landscape and is overgrown with grass. The materials of the facades are local stone, tar treated wood and glass.

To make room for a surprisingly large number of guests in such a tiny space, the architects found inspiration in ancient lodging traditions: The space in the center serves as gathering place, and the beds along the walls provide a spot to sit comfortably around the middle of the room in the evening — one piece of furniture for socializing, eating and sleeping. A narrow nook by the entrance accommodates cooking equipment and storage. △

The Beauty of Use

Hidden in the Japan Alps, a Czech-born artist makes woodstoves that match the simplicity ofJapanese interiors.

Secluded in the Japanese Alps, a Czech oven-maker and his Japanese artist wife find creativity in daily life as she weaves rugs from goat hair and he smiths minimalist woodstoves that are as much modern steel sculptures as they are functioning furnaces.

“In November, the mountain puts on her autumn kimono, and it is lovely around a burning stove...”

The first time I saw one of Jirka Wein’s stoves, I was visiting friends in Matsumoto, a city in the valley that stretches along the eastern flank of the Japan Alps a few hours west of Tokyo. It was March, and I had arrived from California braced for the icy floors and bone-chilling drafts typical of Japanese houses built in the traditional style, which is to say without insulation or central heating. Instead, I stepped into a deliciously warm and cozy enclave. There in the entryway sat a fat black stove unlike any I had seen before. Woodstoves are not unusual in heavily forested rural Japan—I had owned one myself when I lived there, as had a number of my more rustic friends—but this one was glossy and sleek, stripped of any frill that might obstruct its absolute simplicity. It looked as much like a sculpture as a functioning furnace. A lively fire flickered against the round glass door, and above that, behind a second door, a pan of pasta baked in a brick-lined oven.

"It looked as much like a sculpture as a functioning furnace."

My friends were quite taken with their stove. It was like a pet, they told me, or a fifth family member with a knack for bringing together visitors and residents alike in toasty communion. Its origin was equally interesting: It came from a remote valley in the mountains south of Matsumoto where Jirka Wein, a seventy-three-year-old Prague-born artist, shaped steel while his wife, Etsuko Seki, wove rugs from goat hair. My friends had driven out to pick up their new acquisition and ended up staying to talk about poetry and pottery and wine—all, of course, while gathered around the inviting flames of a woodstove.

Visiting the oven-maker

I was so intrigued by this story that on returning home I called Wein to ask if I could visit the next time I was in Japan. He agreed, and six months later I found myself sitting beside him as he drove east toward his house from the small train station where I’d arrived. By then it was early November. It had rained the previous night, and as we climbed into the hills, the damp tree trunks stood out like black fault lines against the brilliant foliage. Wein, a grandfatherly man in suspenders and a plaid shirt, seemed as overwhelmed by the beauty of the landscape as I was. “We see the color descending from the top of the mountain, and one day it swallows the place where we are,” he said. His parents had been avid mountaineers, he told me, and the family spent summers in the mountains of Bohemia, instilling in him a lifelong love for alpine wilderness.

A life journey from Bohemia to the Japan Alps

His path from those mountains to these was far from direct. Wein grew up in the suburbs of Prague and studied stage design there before moving to southern France to pursue a master’s degree in art history and archaeology. By the time he graduated in 1973, the political situation in Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia had made returning home impossible. He spent the subsequent decade as a wandering scholar, artist, and spiritual seeker. At a Gandhian ashram in India he learned to spin, and in Santa Cruz, California, he taught weaving. By the early 1980s, he was living at a commune in New Mexico. It was there that he met the itinerant poet and environmentalist Nanao Sakaki, who eventually led him to Japan.

“Nanao was living up in the mountains in an abandoned bear den, writing a play,” Wein recounted as he turned onto a narrower branch of the winding road. “He would come down to the commune to restock. We’d spend all night drinking and singing, and then he would go back up the mountain.” The two became friends and eventually traveled the western United States together, staying with the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. When Sakaki returned to Japan, he wrote to Wein, inviting him to follow. “So I came. It was winter. Then spring came and the mountain was so beautiful I couldn’t believe it,” he said. Thirty years later, he hadn’t left.

At home with Seki

Wein rounded a final curve and pulled up in front of a large old-fashioned house hemmed in by wooded slopes. It was a perfect mild morning, the sky clear, the smell of smoke mixing with the sunlight. From somewhere far below, I could hear an invisible creek rushing past. Wein led me inside a cavernous entryway. The 140-year-old house had belonged to a powerful landowning family, he explained, but by the time he and Seki arrived with their daughter in the mid-1990s, it had been abandoned for decades. A flood had washed away all of the other homes in the hamlet, leaving only monkeys, deer, and wild boar for neighbors. Now, restored, the house was spare and majestic, composed of age-darkened wood and dusty plaster pierced by shafts of light. Gazing out at the wall of trees that pressed in from every window, I asked him if he ever tired of the mountain. “No, never,” he replied, deep smile lines radiating from the corners of his eyes. “I hope it doesn’t get tired of me.”

In the kitchen, Seki, a small, reserved woman in indigo farmer’s pantaloons and a blocky top, was arranging slices of cheese and tomato on top of pizza dough for our lunch. She nodded hello, then carried the pan over to the large stove in the center of the room, opened a side door, and slid it in. Wein donned a pair of black-rimmed glasses and joined her beside the stove.

“You see these two holes on the top?” he asked, pointing to pipes embedded on either side of the chimney. “These suck in warm air from above so that it creates turbulence.” He struck a wooden match and held it above one of the holes; the flame was instantly pulled straight down by the draft. He walked around to the front and told me to look in through the glass window. Behind the crackling flames, I could just glimpse rows of yellow firebricks similar to those used in ceramic kilns. “Wood flames at 600 degrees Celsius. Firebricks accumulate heat, and after they reach 600 it’s hard for things not to burn,” Wein explained. Together with the air system, the brick lining ensures that his striking stoves burn well, which is why they are as popular with his elderly neighbors as they are with design-conscious urban architects.

Wein has been refining this design nearly as long as he has been in Japan. Not long after he accepted Sakaki’s invitation to cross the Pacific, he met Seki, who at the time was weaving rugs in Tokyo (she has exhibited them nationwide). The pair soon moved to a small village not far from their current home. They grew most of their own food and made what they could by hand, learning from their self-sufficient neighbors. “We wove rugs and grew wheat and rye, and when we wanted to make bread, I thought about making a stove,” Wein said.

“We wove rugs and grew wheat and rye, and when we wanted to make bread, I thought about making a stove.”

He found himself fascinated by both the engineering challenges and the aesthetic ones. Older stoves were made of cast-iron parts assembled with screws. Newer ones had heat-resistant sealing materials between the parts and other additions such as catalytic converters that needed periodic maintenance. Wein imagined something completely different. “I wanted to make one without many technical tricks, that was simple, efficient—and for me this is very important—it had to be beautiful and fit well with the simplicity of Japanese interiors,” he said.

“It had to be beautiful and fit well with the simplicity of Japanese interiors.”

His solution was to weld rolled steel into simple forms assembled with the absolute minimum of fixtures (rolled-steel stoves are now available from many companies in Europe and the United States). The steel sheets are made by compressing hot metal between rollers and cooling it in an oil bath, which produces a rust-resistant surface that does not require paint. Since there are no small passages to become blocked by soot, his stoves can burn soft woods such as cedar that are plentiful in Japan. They are also durable and easy to maintain. He patterns their forms on the asymmetries of the natural world, because “if they were perfect circles or rectangles, you would get tired of them.” Each model is named after a plant or animal: peach, wolf, acorn, Japanese plum.

At first Wein did nearly all of the manufacturing himself while continuing to weave alongside Seki. By the early 2000s, however, he was making stoves full time in order to meet demand. Today he splits production between his home and several small family-owned factories in the prefecture: One laser-cuts the steel based on his designs, another rolls it, and a third handles the welding, with his help. The wooden handles come from a craftsman in the Tohoku region of northern Honshu. Wein cuts the firebricks and finishes the stoves himself, at the rate of about one per week, in an open workspace tucked against a lush hillside behind his house. He told me he likes this division of labor.

“When I’m here, I’m like a wild monkey. When I go there [to the welding factory], a bell rings at 10:00 and it’s teatime,” he said, settling into a bench beside the large slab of wood that serves as a kitchen table. Seki opened the door on the side of the stove and pulled out the pizza, releasing a gust of garlic and seared dough into the warm kitchen. She set the pan on the table next to a large bowl of salad greens and sat down across from Wein. As we ate, she talked about her work as a weaver, and I realized that although she is the quieter of the two, her clarity and strength of vision easily match his.

“We make functional things. When people use them, they create the beauty. In Japanese we say yo-no-bi,” she told me. Wein nodded: The expression, which literally means “the beauty of use,” is essential to him as well. It describes the tracks of rust that bloom from scratches on his stoves, the resonance of her earth-toned rugs against the wooden floors, the way their handmade dishes come to life when piled with food.

“We make functional things. When people use them, they create the beauty.”

“Daily life is quite a creative thing,” Seki continued. “Beauty is very important for our heart and spirit, so how we live is important. When I was thirty-nine, I came to live in the mountains. At first I was so shocked. It was too different, and Jirka was quite strict.” He interrupted: “In the beginning I didn’t want to have a fridge, because when you have one you don’t eat fresh things.” Seki continued. “Those ten years made me very strong, and they changed me. After ten years, nature became very close. Lately, Jirka goes to sleep early, and I’m up late. I hear deer crying, and I feel like we belong to the same community of living things in nature. I feel deep joy.”

Lunch had ended, and our conversation was winding down. “Jirka, should we make coffee?” Seki asked. “I’ll grind some,” he replied. They moved together to the kitchen counter, where Wein pulled out a hand grinder. Seki filled a pot with water and placed it on top of the woodstove. Imperceptibly, the beauty of use settled another layer onto its smooth black surface. △

Trollstigen Visitor Center Norway

Designed by Reiulf Ramstad Architekter, the visitor center and viewing platform dramatically enhance the experience of Norway's wild nature and landscape.

Oslo-based Reiulf Ramstad Architekter (RRA) has a reputation for bold, beautifully simple Scandinavian architecture — from groundbreaking civil buildings to private Nordic holiday lodges — all bold and unhesitating in form yet free of pretense in their assertion in the landscape.

Alpine Modern has previously covered one of Ramstad's residential designs, the V-Lodge.

Now, German photographer Lars Schneider of Outdoor Visions shot one of RRA's public works for us, the Trollstigen Road Visitor Center. Opened in 1936, the Trollstigen National Tourist Route stretches 106 kilometers (66 miles) through West Norway's mighty nature. Ramstad's firm designed the visitor center to enhance the experience of rugged mountains, waterfalls and deep fjords.

Lars Schneider's report from the road

"I was on assignment in Norway, shooting for an outdoor clothing brand. The night I captured these images, after the client and the models had left for the hotel at one o'clock in the morning, my assistant and I decided to spend the rest of the night in the mountains. The sky looked promising, and the sun rose at 3:30 am that time of year.

"We lingered around the visitor center for a very long time. Besides taking in the spectacular views and the sensational light, we quite enjoyed the fact that we had all this to ourselves. During the day, droves of tourists swarm Trollstigen, eager to take tight hairpin turns winding up and down the steep mountainsides and to take in the untamed Nordic vistas. Not having to share all this with anyone was immensely gratifying.

"The architecture is grandiose. Everything very sophisticated, rectilinear, pure, considered... yet beautifully assimilated into the scenery." △

Context and Contrast in the Alps

An Austrian vacation home’s design references its mountainside setting and expansive views across the valley

The 106-square-meter (1141 square-foot) home’s design is based on a flow of rooms that follows the terrain’s slope and an open floor plan organized on three levels. Covered loggias extend the living levels upslope and downslope, creating interfaces with the alpine surrounding. The black wood structure confidently makes its mark in a heterogenous setting.

The client’s program for this vacation home near Zell am See in the Austrian state of Salzburg was simple: a great room with integrated kitchen and dining, sleeping quarters with an en-suite bathroom for each bedroom, a guest suite, and a covered outdoor space that offers mountain views from morning until evening. A carport and practical storage spaces were to round out the project.

Design trilogy

The design by architect Thomas Lechner, principal and founder of LP Architektur, is organized in three areas: arrival, function and living. Positioning the house in the context of building on a mountainside with majestic views as “counterpart” was of the essence.

The first area — arrival — is situated directly down by the street, with a carport plus storage room as prelude. Ascending to the vacation domicile, long stairs coil near the top and reorient the visitor toward the valley and the surrounding mountains.

The entrance to the house creates the interface to the second area — function — with functional spaces on one level. One has arrived, may want to hang up his or her coat and perhaps use the powder room.

Passing through the space dedicated to the arrival, the interior opens to the third area, the great room, which is arranged and organized in three levels that follow the slope of the mountainside. Single flights of stairs connect the living levels. Kitchen and dining are in the center, a fireplace area below and a space to read above. The grading creates each area’s back, providing a sense of security. Despite the spaces’ connectedness, each level is differentiated by its distinct formulation. The center area is dominated by the view out the window dominates, with the mountains as theme, like in a painting on the wall. The levels above and below, however, can be interpreted as interfaces to the outside, with covered loggias extended each respective room to the outside and opening it up into nature. The open-sided rooms offer a protected space for being outdoors during its assigned time of day. The level with the fireplace thematizes the relationship to the surrounding mountains and the panoramic views, while the reading level signifies retreating to a confined space in reference to the immediate surroundings.

The main living area leads to the north-east-facing bedrooms, each with its en-suite bathroom, which then also belongs to the house’s function part.

Compress and release

The house’s overall concept comprises a variety of spaces and rooms, each offering distinct individual qualities. Depending on needs and mood, one can retreat, disappear, feel snug. Yet the home also offers opportunity to experience the expanse and freedom of the alpine landscape unfolding outside.

This contrast, the polarity, is also reflected in the choice of materials. Painted black on the exterior, the timber structure confidently claims its space within its surroundings. By contrast, the light, warm interior affords a comfortable environment where one can relax and recharge. △

Narrow Escape

Falling in love with an impossibly narrow lot on a mountain village's main street, A Denver architects builds a 15-foot-wide weekend home for his adventurous family

Incited by a seemingly impossible building site in an old railroad town above Vail Valley, Colorado, a Denver architect designs a 15-foot-wide sustainable mountain getaway as a speculative investment for sale. Then his adventurous family falls in love with the home. It was an eyesore. Passersby merely saw a ramshackle trailer overstuffing the 25-by-100-foot (7.5-by-30-m) lot on Main Street in Minturn, Colorado. Yet, André Vite spotted an opportunity.

The campus architect at the University of Colorado Denver and his wife, Ginger Borges, an oncologist at the University’s medical school, have a weakness for obscure properties. That evening three winters ago, however, they maintain they were not scoping out a new venture at all. The couple and their preteen sons, René and Niko, were headed to the old railroad town up Eagle River for dinner after a day of skiing in Vail. “We drove through Main Street Minturn, which is a town we go to all the time, and there was a mobile home for sale that was just totally wedged in and awkward looking,” Vite remembers.

Even though he didn’t know what to do with it at the time, the architect wanted that piece of land. And he got it without difficulty because the city planners had been eager to get that blot off Main Street.

The draftsman went home and started sketching.

S(e)izing the Opportunity

The lot’s appeal was twofold: It was located right on the town’s main stretch and it was zoned for mixed use. “From a planning and zoning standpoint, it was a fantastic opportunity,” says the architect and urban designer, who also heads his own practice, the Vite Collaborative. (Or, as he describes it, “A bunch of friends working on unique projects together.”) If for nothing else, Vite purchased the property at a propitious time. The shops along Main Street had been expanding in that southern direction in recent years. Thus, Vite had originally designed the project as a residential spec home with the option for retail or commercial space on the ground floor.

While the sliver of land overlooks the principal artery of town life on the Main Street side, the opposing end couldn’t have more different surroundings — a quiet residential street with community gardens across the way. “From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building,” Vite recalls. “Both facades relate to the context of the side they are on.”

“From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building.”

Yet another challenge the building site posed was the 10-foot grade change between the two frontages — an entire story difference, front to back. That was not all. The town’s zoning laws required a 5-foot setback from the property line. The house could be only 15 feet wide.

Fortunately, the neighbor’s garden to the south and a driveway next door to the north give the narrow site extra breathing room. “It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light,” Vite says.

"It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light."

Unconstrained creativity on 15 feet across

The building constraints — the narrowness, the contrasting major facades, the steep slope — only spurred Vite’s imagination and inspired innovative solutions. How did he create a modern living space — an entire three-story house — with 15 feet (4.6 m) across to work with? The architect’s answer was a structural steel frame, an element adopted from commercial construction, which gave him the structural freedom to engineer large open spaces on the inside. “It’s a steel moment frame structure with three beams that go all the way down the building. Then there is a steel beam across the top.”

The steel beams manifested what would become part of the narrow house’s legacy, and with it, a close relationship between Vite and the local builder, Brian Beckett. “When he was erecting the moment frames, Brian called me and said we can’t put the roof on tomorrow,” Vite says. One of the moment frames had been a quarter-inch off plum, which was still well within building tolerances. As might be expected from the sanguine architect, the holdup was anything but a point of contention; on the contrary. “To have a guy who takes this that seriously was just really important to me. I knew I was going to get a great building from him,” says Vite. “The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

“The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

Actually, there was one moment during construction that did stop the architect in his tracks. After Beckett put the roof on the now-perfect steel frame, he took a picture and sent it to his client in Denver. “It looked like a tube; like you wouldn’t ever want to live in anything like it,” Vite remembers his initial reaction. “It wasn’t until we started finishing it out that it turned into what we’ve got. But that was a scary point, because it was so narrow.”

Family first

By the time construction was completed, the next ski season was approaching. Vite and his family had frequently driven up from Denver to ski in the Vail Valley during previous winters. “We decided we would use the house for that ski season,” Vite says about the investment property he had just finished. “We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

“We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

The unique house itself wasn’t the only reason the family never wanted to move out. “We absolutely fell in love with Minturn. It’s the real authentic mountain community between Beaver Creek and Vail, where you have all these people who are transient and vacationing. The people in Minturn are really the ones who keep that valley going,” says Vite about the mountain town’s thousand or so residents.

What’s more, Borges not once considered her husband crazy for building this improbable house. “We’ve been married for twenty years,” Vite laughs. “She is used to that.” And attuned to narrow dwellings she was. The first home the couple restored and lived in together was a townhouse in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood that was only 14 feet wide. “She’s getting an extra foot,” Vite exclaims, insisting his wife was thrilled about the idea to keep the Minturn house. Now the four escape up here nearly every weekend, year-round, to fish, drive their go-kart, hike — or ski in winter.

Open space to monkey around

Since completion, the house has evolved into a fun destination in its own right for the adventurous family. “The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open,” Vite says. Scarcely any interior walls partition intimate bedrooms and private bathrooms from the open, free-flowing floor plan. At the bottom, the concrete foundation encases a below-grade guest bedroom and bathroom on the dwelling’s Boulder Street side. Because of the steep slope, the opposite end is above ground, where the garage faces Main and can be extended out to the street for a future retail space.

“The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open.”

The ceiling of the modern living room on the second floor rises two stories with an overlooking loft, the parents’ open bedroom. The boys’ west-facing bedroom is tucked behind the “master” (or in front of it, depending on which frontage you interpret as the face of the house).

The family spends most of their time together in the open living space with the curved white couch. “We take this big picture off the wall and project movies onto the wall.” The cork-floored main living area flows outside through a folding glass and steel wall that opens up to the deck. A minimal dining area in the middle transitions into the kitchen, Vite’s favorite spot in the house.

“But what the kids love is this 26-foot space here,” says Vite, pointing at the high living room ceiling, where he mounted a climbing rope. “They get to climb up this wall that’s all blocked with wood, ready to put in finger holes for a climbing wall.” Climbing is indeed the boys’ favorite indoor pastime. “They climb everything they can get to,” their father reveals, pointing to a trolley that runs down the steel beam under the roof above the master loft. “You can strap yourself onto here and then push off.”

In addition to providing a place for the family to escape the city on weekends and holidays, Vite wanted to set the stage in the house for a few cherished vintage pieces he inherited from his late parents. “The interior design was all about finding a home for my father’s old furniture he had bought in the early sixties in New York. It’s all authentic midcentury-modern furniture, and I designed the interior around it.”

Sustainability as style

The LEED-accredited architect is reluctant to categorize the architectural style of his idiosyncratic house. “What they call it up here is a contemporary mountain home, because it very much has the feel of a timber frame, although it is done in steel,” he says. “But rather than talking about a style, the sustainability feature is more important to me.”

From the construction standpoint, the house is based on a standard wood module to limit material waste, which actually got Vite in trouble with one particular Minturn resident. “There is a guy up here who goes around the construction sites, picking up wood waste for his wood-burning stove at home. He would complain that we didn’t have enough wood waste and gave us a hard time.”

The carefully calculated use of exterior wood is to protect the building from driving rain in support of the actual weather barrier behind the wood. “All these gaps are open,” Vite shows. “It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.” Air exchange is critical for a highly insulated house at this altitude, where the air is extremely dry. “You are living and cooking and doing all these things that increase the humidity inside the house,” he explains. Instead of trapping the warm, very moist air inside, the house can breathe it out. Vite also installed a heat recovery air exchanger that pushes warm, inside-air to heat colder air coming in to ventilate the house, without using the heating system.

“It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.”

Vite received the 2013 Award of Citation from the American Institute of Architects for this project.

Tight house, tight Community

Being awarded such a significant professional accolade from AIA is nice, sure, but what truly warms the architect’s heart is how the locals perceive the standout structure they’ve come to call the “skinny house.” “We get compliments on it all the time. People are stopping by, saying they’ve watched it go up and want to look at the inside,” he says. “I love that the town loves the house.” △

“I love that the town loves the house.”

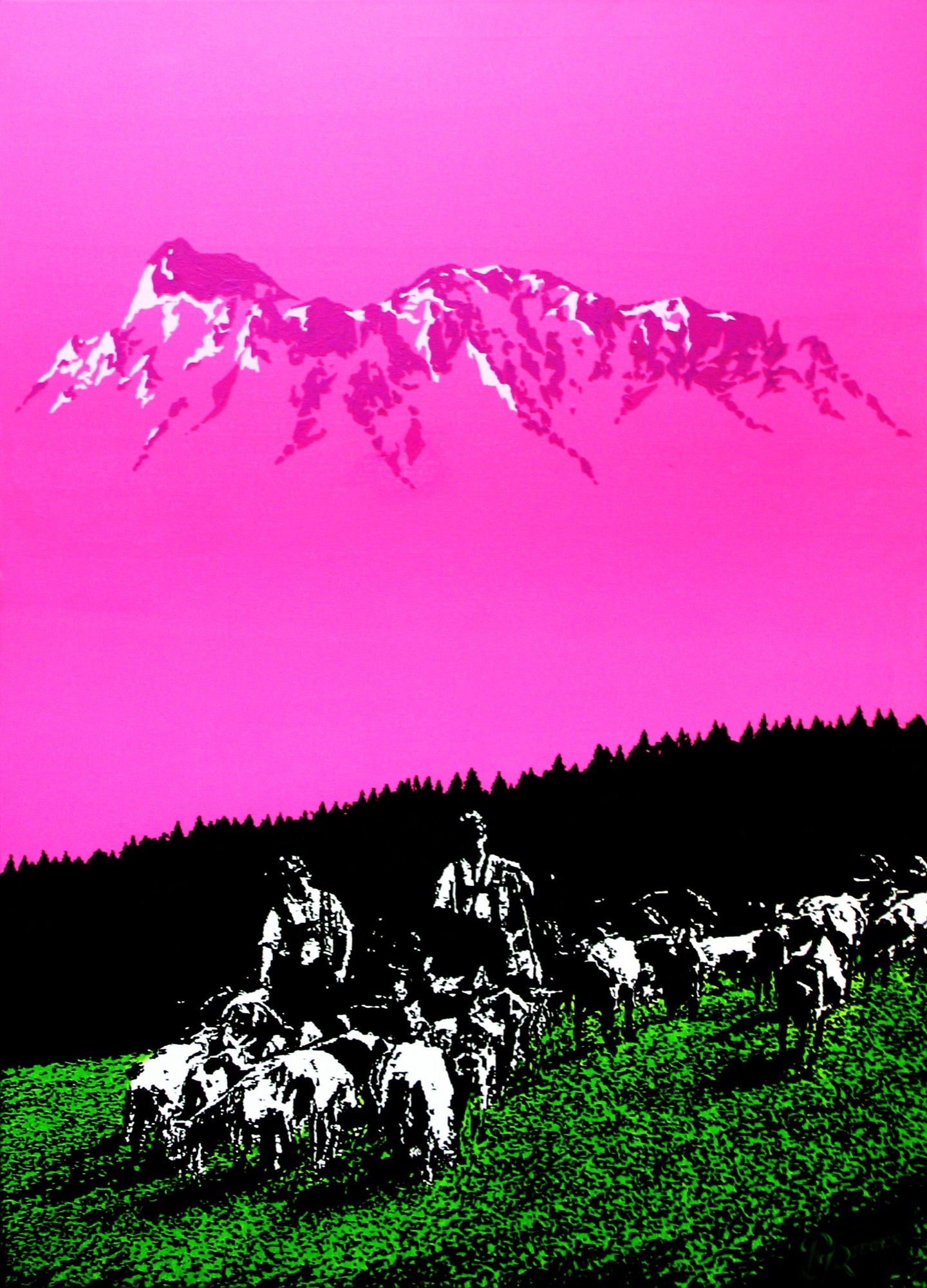

Bavarian Rebel

Avant-garde artist Bernhard Rieger — master of Lüftlmalerei, inventor of alpine pop art

A master of Lüftlmalerei, the traditional fresco technique characteristic of the Bavarian Alps, avant-garde artist Bernhard Rieger now revivifies authenticity with his invention of alpine pop art.

"Schau, wie die Sonn' aufgeht. Vom Berg ins Tal. Und von der Alm in die Stadt."

(Watch the sun rise. From the mountain to the valley. And from the pasture to the city.)

The artistic wunderkind

The funky music and the visuals on Bernhard Rieger’s website, alpenterieur.com [editor's note: for the best experience, open the link and listen to that intro beat and indigenous vernacular as you continue reading...], unmistakably manifest the Garmisch-Partenkirchen-based artist’s unusual style, which interweaves ancient tradition with modern design and sound to create something altogether original. The alpine electro beat he composed himself is just one example of the eccentric mountain rebel’s eclectic work. From his traditional Lüftlmalerei to alpine pop art to his modern designs with reclaimed wood, Rieger chooses a bold new approach to traditional art forms and materials. The man himself is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a walking paradigm of the young, wild generation of the European Alps.

Rieger’s website intro mixes original digital music—house, electro, lounge, and dump beats his musician friends composed—with acoustics like the cowbells he recorded in a pasture. The instrumentals are overlaid with his father’s voice speaking in the indigenous dialect of the Upper Isar Valley. The music, says Rieger, is his interpretation of the tightrope walk between cultural roots, modernity, and urbanization. He passionately philosophizes about society’s rekindled longing for regional culture and tradition. Rieger himself has never turned his back on the ancestral lifestyle. Growing up in the mountains surrounding the legendary tourist town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Upper Bavaria, he was deeply rooted to his native soil. He has never lost that authentic sense of life people now long for again.

Alpine minimalism

The idiosyncratic artist hails from a 400-year-old farmstead his parents lovingly restored and renovated in his childhood. Rieger’s father, a carpenter and sculptor who learned the trade at the Garmischer Schnitzschule (woodworking school of Garmisch), passed down his passion for South Tyrolean culture and style and for working with natural materials, wood in particular. Like his father, Bernhard Rieger is fascinated with the alpine farmers’ minimalist way of life, which continues to inspire him. Rieger grew up among folks who live by nature’s rules and rhythms. And even little Bernhard was blessed with a talent for painting.

“I painted gigantic murals with wooden pencils when I was only four years old,” Rieger remembers. Not to say that his affinity with local traditions has always been unshakable. As a youngster, he wore the baggiest jeans he could find and was more interested in his skateboard and punk rock than lederhosen and cowbell music. Nevertheless, he continued to express himself creatively throughout adolescence, whether it was through drawing tattoos and band logos for his classmates or designing skateboards and snowboards for himself and his buddies.

Flunking fine arts

He secured his first commissioned work at age fourteen. “I earned my first money designing certificates and painting wall murals,” Rieger recalls. What’s more, an odd job at a junkyard exposed him to old materials he took home to build lamps and other objects. After he graduated and completed his military service, Rieger was not accepted by the Akademie der Bildenden Künst München, where he wanted to study interior architecture. Instead, he trained as an interior designer and started his own business. “My unconventional style and my maverick projects were a thorn in the academy’s side,” Rieger reckons.

Lüftlmalerei

His original style fully flourished during that time. He practiced traditional Lüftlmalerei alongside his work as an interior designer. The large-format murals rooted in the Italian Renaissance first found their way to Bavaria via wealthy merchants in Augsburg who wanted their city houses adorned, and later they spread to the villages and the countryside. “Until 1850, this style, inspired by the fresco technique, was tremendously popular in the foothills of the Alps, from Arlberg to Salzburg,” Rieger says about the profane art style with its sacral motifs.

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.” Rieger also paints maypoles with traditional patterns and pictures, one example being the famous maypole at the Munich Viktualienmarkt. “You can’t reinvent the wheel with Lüftlmalerei, though. It’s practiced the way it always has been, drawing inspiration from historic buildings.”

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.”

The beginning of alpine pop art

In recent years, Rieger needed to break away from the rigid images and patterns. And he did. Since then, he has been successful with his own distinctive interpretation of alpine art. One of his works was a large hotel facade in Garmisch. The sixty-square-meter (646-square-foot) fresco depicts a mountain-climbing scene—very modern, very abstract, very bright red. “It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist,” Rieger proclaims. “Then you don’t understand your calling.” His alpine pop art was born from this mindset. It’s a modern interpretation of the nostalgic, schmaltzy scenes from his parents’ and grandparents’ era, in jarring colors. The small-town conservatives declared him crazy for it. That didn’t bother him. No doubt Rieger remains a colorful character in the region, not least due to his appearance, distinctly reminiscent of a young King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

“It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist. Then you don’t understand your calling.”

Alpenterieur

When it comes to Europe's modern alpine art, there is no way around Rieger. This is also true of his interior designs. Since 2007, the artist has been uniquely reinterpreting alpine living under the label Alpenterieur. While his lines are modern, his rugged reclaimed surfaces tell legends of the past, like the lines on an old mountain farmer’s face.

He knows not everyone can afford the elaborate artisanal designs he creates from natural materials. That’s why he added affordable Alpen Kult Quadrate, made from reclaimed wood and felt, to his collection. “You can find them hanging in the quaint living rooms of old Garmisch ladies and the fanciest homes in Kitzbühel,” Rieger says. He’s already made thousands of the squares, not mass-produced but handmade—and he’s making more. He believes everyone should have a piece of his creativity. And his artistry is blossoming. Right now, he says, he senses a rush of emotions again like he did during puberty, a sign something new is on the horizon for him. What exactly it will be, he doesn’t know yet. But he imagines it will have something to do with ancient custom and tradition. The trend of modern design inspired by the simple mountain style of the past is growing. “Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated,” Rieger says. “Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”

This lifestyle trend is Rieger’s livelihood. But even more so, the Bavarian rebel walks the talk. His bohemian persona and alpine pop art certainly do marry the mountains and the valley, the pasture and the city. △

“Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated. Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”

Sense of Place: Designed for legacy in Aspen

Mountain homes in Aspen, Colorado, are built to stay in the family for generations

Aspen is steeped in tradition. Generation after generation, families vacation at the posh resort to ski in winter and to celebrate the town's famous festivals in summer. Slope-side chalets and opulent second homes alike are built for legacy, as venues for extended family to gather and carry on traditions, season to season. A continuity that translates into architecture and decors of great depth and layering.

Nevertheless, even mountain folks for a fortnight must have functionality alongside style, beginning at the entry. “There is that sense of arrival at a mountain home,” says Sarah Broughton, co-owner of Rowland and Broughton (R+B), an architecture and interior design firm in Aspen and Denver. Aspen homes are planned with the understanding that one comes in from the elements. “People need to be able to knock snow off their boots.”

"Aspen homes are planned with the understanding that one comes in from the elements."

Style without borders

Many of R+B’s clients have primary homes on the beach or in big cities, all over the world. “One thing that is important to them is that they really feel they are in Aspen,” says Broughton, a modernist at heart. To achieve this sense of place, she relies on natural materials such as wood, grasscloth, and natural stone — “things you see when you look out the window.” What’s more, treating woods in surprising ways, such as planking or wire-brushing, brings out something special in a natural material.

Broughton complements mountain settings and modern, clean lines with cashmeres and wools in the furniture and textiles. She loves to add ample pillows and throws on beds and couches. “Hemp, wool, and cashmere textures and patterns can speak to a natural environment without being literal,” the award-winning architect says. The beauty of sunlight falling through an aspen forest’s canopies, for instance, can translate into a pattern. Twinkling lights become reminiscent of a starry winter night in the Rocky Mountains.

“Hemp, wool, and cashmere textures and patterns can speak to a natural environment without being literal.”

Black Birch Modern

With its clean-lined, minimal design, Black Birch Modern in Aspen is an example of a mountain retreat that not only boasts stunning alpine-modern architecture, but is warm and welcoming to boot. R+B achieved this balancing act by bringing outdoor materials inside. That, Broughton believes, is something anyone can do at home. “Carrying a material found around the outside of the house into the flooring, for example, is an effective way to blur that indoor-outdoor line, which is such a quintessential element of Aspen style.”

Bringing Aspen home

Give your home a touch of Aspen flair and make room for your own legacy. Create spaces where friends and family can gather to share food, drinks, and stories, while they sink deeper and deeper into your cashmere pillows and pull up their feet under a wool blanket.

Art from an Aspen gallery adds a fine finishing touch. “Bringing in local talent is a nice way to tie it to the place and a great way to modernize a home,” Broughton says. “Make it feel collected and not staged,” are her parting words of style wisdom. “Modern design has a lot of depth and layering to it. It’s not a one-hit wonder.” △

“Make it feel collected and not staged. Modern design has a lot of depth and layering to it. It’s not a one-hit wonder.”

A Whistler A-Frame

Scott & Scott Architects design an outdoorsy Vancouver family’s dream cabin

If the multiple languages and accents overheard in lift lines and on gondolas tell any kind of a story, it’s that everyone from everywhere with a serious interest in skiing or snowboarding is making a beeline for Whistler Blackcomb. More and more of those visitors are putting down roots with a second home in this outdoor wonderland north of Vancouver, Canada. Some buy condos in the heart of Whistler Village or townhomes with ski-in/ski-out access to the slopes. Others build luxurious heavy timber colossi in swank residential areas that have grown up around the resort’s edges.

No matter their size, most of these mountain retreats share the following design elements: wilderness building materials, either structural or decorative, and floor plans and amenities that mimic those found in city interiors.

While there is nothing wrong with having a second home in the mountains that works much like a primary one in the city, some younger ski and snowboard families have begun to question why they would want to occupy such a space when a more indigenous—and much radder—alternative is available: an iconic A-frame cabin.

Return of a classic-modern icon

Ah the A-frame, that staple of mid-twentieth-century vacation home vernacular that was massively popular across the North American outback from the 1950s through the 1970s. There is no way this odd-looking triangle-shaped structure, which got its start in ancient days as a roof hut in Japan and a storage shed in Europe, could be mistaken for anything urban. Attempts in the sixties and seventies to make it a city building resulted in churches, fast-food joints, suburban houses and motels that were novelties even then.

The classic post-Second World War A-frame cabin was a purpose-built backcountry bolthole. Its simple construction, minimal building materials and absence of fancy finishes made it a preferred DIY project for Mad Men-era handy men, and in the 1960s, A-frame cabin kits sold briskly. Most of these ready-to-assemble weekend homes shot up in snowy locales.

One reason for this is the A-frame’s radical roofline that extends down to the ground on two sides, which helps shed any snowpack. Another is its ability to capture natural light. The A-frame’s roof supports all of the building’s weight, freeing up the gable ends to be filled with wall-to-wall glass.

A third reason for its easy fit in alpine terrain is one you might not have imagined given the A-frame’s modern, inorganic appearance. In this landscape, it can be a chameleon, a slender, weathered wooden form indistinguishable from evergreen trees.

For all of its baked-in virtues and utter lack of pretense, the A-frame is enjoying a renaissance. Outdoor types who value authenticity are enthusiastically rescuing original 1960s and 1970s models, hand-building replicas (check out the Urban Outfitters online journal for directions on "How to Build an A-Frame Cabin") or commissioning fresh versions that honor the building's honest materials and original intent, which is what Vancouverites Melanie and Brenton Brown did when they gave the go-ahead for the elegant update pictured here.

A family’s dream

For years, the outdoorsy couple and their energetic offspring, Daisy and Finn, now eight and 13 years old respectively, bunked off and on with close friends in their 1980s A-frame in Whistler’s Emerald Estates neighborhood. In 2014, the family decided to build their own variation on a property up the street from their friends. “We wanted a new cabin that would not look out of place with the older ones in this area,” says Brenton, CFO for the Vancouver-based digital commerce platform Elastic Path Software. “An A-frame felt like the perfect fit for us,” says Melanie, who is an interior designer. “It has a retro feel we love and, obviously, we knew what we were getting into with this type of building.”

Idiosyncratic Emerald Estates

If you wanted to build a new A-frame in Whistler, idiosyncratic Emerald Estates would be the right place to do it. It is one of Whistler’s early neighborhoods, dating to the 1960s when the community mainly consisted of diehard Vancouverites willing to drive 75 miles of nasty road on weekends to ski its pristine powder, full-time construction and seasonal workers, plus assorted ski bunnies and bums.

A-frames are at home in this neck of the woods where a lot of the housing stock still has a throwback vibe. Among its early Whistler building types, Emerald boasts classic 1960s, 1970s and 1980s A-frames and Gothic-arches cabins (their bulbous bow-sided brothers), Heidi-style chalets and quirky hand-built dwellings such as Whistler’s famous “Mushroom House,” where, if Emerald Estates were a fictional fantasy world, Bilbo Baggins would want to live.

Although it is only a 10-minute drive from Whistler Village, Emerald feels off the beaten path. It is still a neighborhood more associated with local families than visitors. Most of the residents are old-timers and full-timers, “not weekend warriors,” says Melanie, laughing to think that this label could be applied to her little tribe.

Emerald’s topography is steep and wooded, with winding roadways that dip to reveal the teepee peaks of A-frames poking out above treetops and that rise to expose wide-roofed chalets juxtaposed with glacial rock formations.

The Browns’ property is open, steeply sloped and pie-shaped: wide at the front and narrow at the back where a four-story-high granite outcrop dominates. The site is high enough up the hillside that the evergreen trees, so plentiful downslope, have no effect on the view. “It’s panoramic, an unobstructed 180 degrees,” says Brenton, pointing north to Weart and Wedge mountains with Armchair Glacier sandwiched between them, then south to Whistler and Blackcomb. The family’s new cabin, designed by David and Susan Scott of Vancouver’s Scott & Scott Architects, capitalizes on all of this scenery.

The Scotts and the Browns

The Scotts are a husband-and-wife team who worked independently for years for prominent Canadian architects before forming an architecture practice together three years ago. Their office/home, which they share with two young daughters, is a converted butcher shop in the Mount Pleasant/Main Street area, currently the coolest neighborhood in Vancouver for young families to live.

Every project the Scotts have completed together has received public praise and attention either in a peer review journal, a lifestyle magazine or on a discerning design website—and sometimes all three at once. This past winter, the Scotts were recipients of the 2016 Young Architect Award from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. It is the first time the society has given this award to a couple.

The Browns were introduced to the Scotts through architect friends who admired their work. After seeing images of the Scotts’ own off-the-grid cabin at the north end of Vancouver Island (it appeared in the inaugural print issue of Alpine Modern magazine), the Browns were smitten with the Scotts’ understated, minimalist design and use of traditional and off-the-shelf materials in interesting and diverse ways.

Elemental, accessible design is what the Scotts are known for. “No one ever actually says this to us, but I think part of our appeal is that what we do is not outlandishly opulent,” says David, “so we end up with young families who want a holiday place in Whistler or Tofino [the surfing capital of Canada] but aren’t into building grand statements.”

“What we do is not outlandishly opulent, so we end up with young families who want a holiday place in Whistler or Tofino but aren’t into building grand statements.”

Working all angles

The Browns’ new A-frame may not be a grand statement, but it is an eye-popper, and when you begin to look closely at the design, you can see that it is an extremely intelligent and refined evolution of a basic building type.

Take the roofline, the A-frame’s defining feature. On a flat site, the roof would sit directly on top of the ground with identical triangular gables at either end. The challenge for the Scotts was how to incorporate these archetypical elements in an innovative way on a steep site.

Their response was a three-story building, narrow at the back and wide at the front just like the shape of the lot, with different-size gables at either end and roof planes that follow the grade.

As with A-frames of old, the Scotts’ roof design is a declaration—but with a difference. Level at the top, the ridge has been pushed out beyond the front façade of the building, then the gables have been pulled back at an angle so that the bottom edge of the roof is now parallel to the slope not the ridgeline. Laying the shingles at this same gradient gives the roof its rakish appearance.

From the rear, the Brown’s cabin appears to be a single story defined by a slender gable tied, in classic A-frame fashion, directly to the landscape, in this case volcanic rock. What you are really looking at is the back end of the third floor, and the space inside is a den, which opens onto the generous patio the Scott’s fashioned from a flat space in the outcrop.

This rock face, which erupts out of the ground at the entry level and slopes up an additional 20 feet behind the patio, has proven to be a huge hit with Daisy, Finn and friends. Says Melanie: “Last weekend we had 10 kids scrambling up from the patio and all over it, along with our enormous silver lab, Rosie. I would be in the kitchen [on the main level], looking out the window and see kids with big smiles on their faces coming down the rock on this side.”

From the front of the Browns’ cabin, each of the stories is clearly visible. The ground level, a rectangular box set into the rock, beautifully rendered in concrete clad in cedar at the front, provides a strong and stable platform for the soaring roof that defines the stories above it.

Design features on the front façade include extra-deep eaves and a large balcony that runs across the front with a guardrail made from aluminum bars used for snowmobile trailers “so it’s easy to sweep the snow through,” says David Scott.

Building inside out

Judicious in their choice of materials, the Scotts prefer their wood locally harvested, their stone quarried nearby and anything ready-made to be plain and pragmatic. The roof is clad in standard red cedar shakes that will weather to the tone of the surrounding rock. Solid structural decking was applied directly on top of the joists “so it works as both floor and ceiling, the way it did in old ski cabins,” says David.

In a classic A-frame, the architectural bones are an interior design feature. The same is true here: the internally exposed frame is made of locally sourced Douglas fir, rough sawn in conventional sizes: 2 by 12 inches (ca. 5 by 30 centimeters) for the joists, 2 by 10 inches (ca. 5 by 25 centimeters) for the rafters. The lumber elements are fastened together using simple lapped joints at the floor and roof connections. “Our preference is to always keep everything consistent and the same, and to highlight the craftsmanship, not conceal it behind finishes,” says Susan.

The cabinetry was built on-site of construction-grade rotary-cut plywood; this wood also encloses stairs that are capped with the same stock aluminum used for the balcony guardrail. The only obvious built-in eye-catcher anywhere inside is the honed marble from Vancouver Island used in the kitchen and living area on the second floor.

The first level is all business: “washroom, laundry, storage for bikes, skis, snowboards, surfboards leftover from our time spent in Laguna, and probably snowmobiles at some point,” says Melanie. The middle level is for communing; the top, for turning in.

One frustration with A-frame design is that it does not allow for much useable space inside; all slope, no sidewall is the common complaint. One original way the Scotts dealt with this dilemma was to put the stairs in a light-filled dormer, freeing up floor space on the third floor for a proper hallway tucked partially under the slope.

The hardy foursome and pooch moved into their cabin a few days after Christmas 2015 and have been using it nonstop ever since, often sharing their holiday home with friends.

Over the winter, Melanie skies with Daisy while Brenton snowboards with Finn. “In the summer, we like hiking with Rosie, as well as mountain biking and swimming in the various lakes. There are several hiking and mountain biking trails in Emerald, and Green Lake is right around the corner and so is the Valley Trail. We enjoy riding our bikes along it into the village,” says Melanie. “If you love being outdoors, there’s just so much to do around Whistler.” △

Simplicity on the Rocks

Built into the mountainside, a Quebec country house cantilevers over the treetops for magnificent views

A rugged mountainside plot in Quebec’s countryside impels a Montreal architect to design a cantilevered minimalist jewel that elevates the main living space above the trees for splendid views of Mount Orford and the valley below.

Imagine you are an architect given a limited budget to build a modest weekend home on an impossibly steep site whose topography mercifully plateaus atop a big rock. If you are brilliant, you figure out how to build the house right on top of that rock, for the best views. At least, that’s what Stéphane Rasselet of the Montreal-based architecture firm has done with the Bolton Residence.

Voilà. “A unique, timeless jewel landed on a concrete base” in the client’s own words. Alain Bernard, who works in film production, dreamed of a small, modern country house for a weekend escape and for extended breaks between intense projects. He had two directives for the designer: respect a curbed budget and maximize the spectacular mountain and valley views the plot of land offers.

These two essentials, plus the rugged wooded site on a precipitous slope above the tiny municipality of East Bolton (Bolton-Est) in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, impelled the architect to design a sculptural structure that addresses the site challenges while presenting prime panoramas of the surrounding nature. “The way Stéphane positioned the house is probably what makes it so unique: anchored in the rock on one side and completely floating at treetop height on the other side,” Bernard says.

The owner of Bolton Residence is usually alone with his two cats at the 1,540-square-foot (143-square meter) house in the country. He also has a studio in the city, where he stays while working umpteen hours during the week. But when he has two to three months off between contracts, he comes to East Bolton to enjoy the peace and take time to contemplate. “Although the house is so comfortable, soothing, and stimulating, it also brings poetic visions and enchantment,” he muses. “Every day, every season, the landscape changes. The light is different, and the colors are renewed. The house was built with the idea of glorifying nature and ultimately becoming part of that nature.”

"The house was built with the idea of glorifying nature and ultimately becoming part of that nature.”

The holistic architect

When Bernard began his search for an architect, he was already familiar with _naturehumaine and loved their work. “They were my first choice, but I was convinced they’re too busy to accept such a small, limited-budget contract.” But an intrigued Rasselet wanted to meet the prospective client. The two men at once understood where each was coming from. “We talked about architecture and design,” Bernard remembers, adding that he sent his architect online to see features of cabins in nature. “I told him to capture the spirit of those cabins in a contemporary house.”

Rasselet’s answer was a strikingly simple design. Nevertheless, it was his masterly attention to the many complex details during design and construction that in the end harmonized this ode to minimalism.

Stéphane Rasselet graduated from McGill University’s School of Architecture in Canada and then worked on major projects in Paris before returning to Montreal to gain experience at local firms. He joined forces with Marc-André Plasse to found _naturehumaine architects in 2004. In 2013, Rasselet became the principal partner at the design-oriented atelier specializing in private residences.

When I ask him to describe the nuances of his design style beyond the obvious “modern,” the architect pauses. “That’s a difficult question. Often, we are absorbed in our own way of doing things, and the comments and opinions people have from the outside become the definition of what we do.”

Overall, the firm’s body of work is characterized by a clarity achieved through minimal choices in materials and colors. Never flamboyant. “We limit things that are expensive, but we push things structurally.”

“We limit things that are expensive, but we push things structurally.”

Environment in view

The Bolton house’s two exalting structural elements are cantilevers and corner windows—both employed to maximize the view.

Good comprehension of the challenging building site was essential to designing the Bolton Residence. Having skied Mount Orford many times, Rasselet was already familiar with that area east of Montreal. And although his client’s plot of land was large, the topography was extremely irregular, leaving the architect but one place to build without racking up prohibitive excavation costs: the large rock at the property’s highest point. Standing on top of that big rock on his first site visit, Rasselet took in the majestic sight of Mount Orford to the north and an expansive eastern view down a wide valley that rises up on the other side to a profile of mountains and the horizon. “It was obvious the house had to be oriented parallel to this line of mountains to the east, with the gable facing Mount Orford.” The scenic views set the structure’s two main axes in stone.

The _naturehumaine architect framed the horizontal view of the valley and distant mountain range with a linear band of glazing along the main living space and floor-to-ceiling vertical glass to maximize the views of Mount Orford on the north side of the house. “We wanted to give the illusion that the ceiling was going through the glass and out onto the terrace,” says the architect. The roof cantilevers out about six feet (1.8 meters) over the terrace.

Geometry in the treetop

Rasselet wants all his clients to think of the interior and the exterior of a house as one. The building itself and what’s inside must be in dialogue. With the Bolton Residence, the architect achieves this holistic approach—as his firm typically does—by designing both the structure as well as the interior architecture: the kitchen, the conspicuous replace at the center of the house, any built-in furniture, and all the metalwork. Steering clear of a look too slick for a country house, he chose materials with a patina and roughness: rugged gray slate tiles from Vermont for the entire main floor, a custom blackened-steel fireplace that shows the weldings, and a ceiling clad in inexpensive, rough construction plywood. A calm, monochromatic color palette without flashy design accents allows the view to become the main protagonist in a dramatically simple architectural play.

The two stacked volumes—long rectangles—hooded with a gable roof are a modern interpretation of the vernacular architecture of the region’s gabled barns. The gable roof is covered in panels of charcoal gray steel that continue down over the sides like a protective blanket. Protruding three feet (ca. 90 centimeters) over the base, the living spaces and master suite on the cantilevered top floor elevate the dweller up and out, giving a sensation of peaceful symbiosis with his natural surroundings. No surprise, this open space with the kitchen, dining room, and replace is Bernard’s favorite spot in the house. He treasures the big mountain views from the kitchen island and the 180-degree surround view that follows the landscape. “You are standing above the treetops like in a treehouse out of a child’s dream.”

“You are standing above the treetops like in a treehouse out of a child’s dream.”

The garden-level bottom volume has a smaller footprint and is a concrete plinth anchored into the mountainside and partially clad in a cedarwood skin. Tucked under the terrace at the gable and protected from rain and snow are the carport and the main entrance, which leads visitors into a small vestibule, from where a corridor leads to the downstairs guest bedroom and a bathroom, and stairs lead up to the main living space.

Big-city expectations meet country reality

When asked about the project’s biggest challenge, Rasselet and Bernard both bring up collaborating with local contractors on its execution. “I was on site every day during construction to make sure the contractors built exactly what was designed,” the homeowner says. “Every piece and part and detail of the house was designed by Stéphane. They had to redo a lot of things twice, even three times, to achieve it.” And his architect quickly agrees that the distance from the city posed a challenge. “Once you get two hours out from Montreal, trying to find people who do contemporary architecture and who do contemporary details gets quite tough,” Rasselet says. He often asked for workshop drawings before letting a craftsman build, bend, or weld what he had designed. For instance, the steps leading from the vestibule up to the living room are covered in bent steel plates that had to match up precisely. As is often the case in modern design, it takes more to achieve a simple, clean look than today’s standard—sometimes more ornamented—style does.

In the end, Rasselet says, “All the ingredients have come together to create a nice little project. It’s one of our best projects.” △

Modern Architecture Ascends in Aspen

Architect Shigeru Ban's dramatic design of the Aspen Art Museum

Inspired by the up-and-down movements of the skiers on Aspen Mountain, the Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate Shigeru Ban takes modern building design to dramatic heights with the new Aspen Art Museum.

The new Aspen Art Museum, which opened in August 2014, became an instant, if controversial, landmark in the precious Colorado mountain town and beyond. Architect Shigeru Ban’s building is like no other in Aspen — or anywhere else. Think of it as a box within a box. The blocky three-story glass interior box is wrapped within an outer box made of wide strips of resin-impregnated paper woven into a grid, permitting light and air to filter in and people to look out. In daylight, the strips have a wood tone. The texture relates to old bricks, the dominant building material in downtown Aspen. The strong vertical and horizontal lines play off the glass in an ever-changing succession of light and dark, bright and shadow.

Up and down — like the skiers

Ban’s concept was to echo Aspen Mountain, the commanding presence just south of downtown. At the ski area, skiers ride lifts to the top and then make their way down. So it is at the museum. Visitors first ascend the stairs or ride a room-sized glass elevator to the only public rooftop space in Aspen, with its open sculpture garden, grand view of Aspen Mountain’s lower slope, and an indoor/outdoor café where visitors linger over a cup of coffee, a light bite, or lunch. The menu changes frequently, appropriate for a museum whose exhibitions change every few months. Then visitors work their way down. Six galleries, three above ground and three on the basement level, have already showcased the works by painters, sculptors, installationists, and multimedia artists. A show in Aspen has a way of increasing an artist’s visibility and renown.

Curating the new