Bavarian Rebel

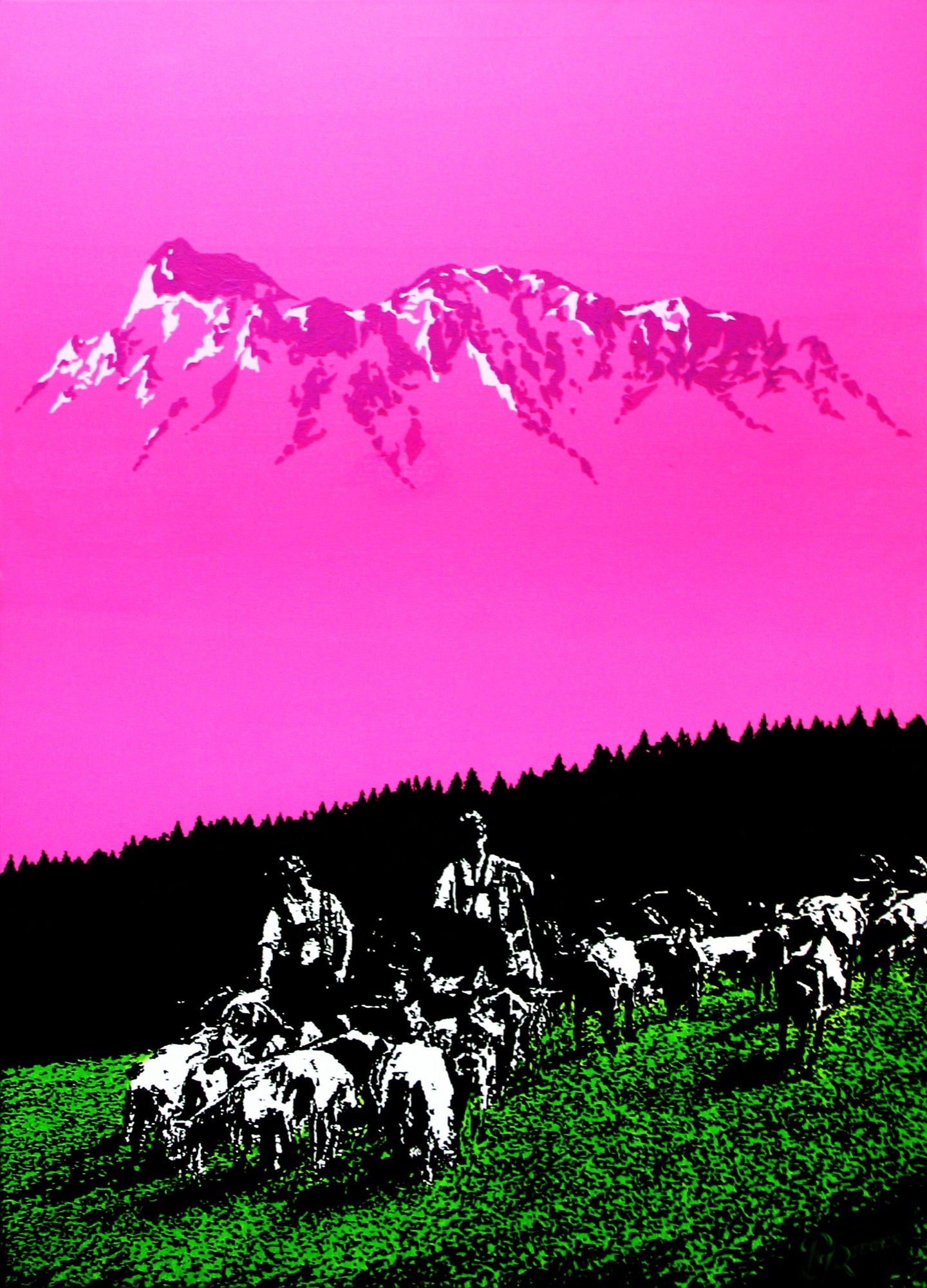

A master of Lüftlmalerei, the traditional fresco technique characteristic of the Bavarian Alps, avant-garde artist Bernhard Rieger now revivifies authenticity with his invention of alpine pop art.

"Schau, wie die Sonn' aufgeht. Vom Berg ins Tal. Und von der Alm in die Stadt."

(Watch the sun rise. From the mountain to the valley. And from the pasture to the city.)

The artistic wunderkind

The funky music and the visuals on Bernhard Rieger’s website, alpenterieur.com [editor's note: for the best experience, open the link and listen to that intro beat and indigenous vernacular as you continue reading...], unmistakably manifest the Garmisch-Partenkirchen-based artist’s unusual style, which interweaves ancient tradition with modern design and sound to create something altogether original. The alpine electro beat he composed himself is just one example of the eccentric mountain rebel’s eclectic work. From his traditional Lüftlmalerei to alpine pop art to his modern designs with reclaimed wood, Rieger chooses a bold new approach to traditional art forms and materials. The man himself is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a walking paradigm of the young, wild generation of the European Alps.

Rieger’s website intro mixes original digital music—house, electro, lounge, and dump beats his musician friends composed—with acoustics like the cowbells he recorded in a pasture. The instrumentals are overlaid with his father’s voice speaking in the indigenous dialect of the Upper Isar Valley. The music, says Rieger, is his interpretation of the tightrope walk between cultural roots, modernity, and urbanization. He passionately philosophizes about society’s rekindled longing for regional culture and tradition. Rieger himself has never turned his back on the ancestral lifestyle. Growing up in the mountains surrounding the legendary tourist town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Upper Bavaria, he was deeply rooted to his native soil. He has never lost that authentic sense of life people now long for again.

Alpine minimalism

The idiosyncratic artist hails from a 400-year-old farmstead his parents lovingly restored and renovated in his childhood. Rieger’s father, a carpenter and sculptor who learned the trade at the Garmischer Schnitzschule (woodworking school of Garmisch), passed down his passion for South Tyrolean culture and style and for working with natural materials, wood in particular. Like his father, Bernhard Rieger is fascinated with the alpine farmers’ minimalist way of life, which continues to inspire him. Rieger grew up among folks who live by nature’s rules and rhythms. And even little Bernhard was blessed with a talent for painting.

“I painted gigantic murals with wooden pencils when I was only four years old,” Rieger remembers. Not to say that his affinity with local traditions has always been unshakable. As a youngster, he wore the baggiest jeans he could find and was more interested in his skateboard and punk rock than lederhosen and cowbell music. Nevertheless, he continued to express himself creatively throughout adolescence, whether it was through drawing tattoos and band logos for his classmates or designing skateboards and snowboards for himself and his buddies.

Flunking fine arts

He secured his first commissioned work at age fourteen. “I earned my first money designing certificates and painting wall murals,” Rieger recalls. What’s more, an odd job at a junkyard exposed him to old materials he took home to build lamps and other objects. After he graduated and completed his military service, Rieger was not accepted by the Akademie der Bildenden Künst München, where he wanted to study interior architecture. Instead, he trained as an interior designer and started his own business. “My unconventional style and my maverick projects were a thorn in the academy’s side,” Rieger reckons.

Lüftlmalerei

His original style fully flourished during that time. He practiced traditional Lüftlmalerei alongside his work as an interior designer. The large-format murals rooted in the Italian Renaissance first found their way to Bavaria via wealthy merchants in Augsburg who wanted their city houses adorned, and later they spread to the villages and the countryside. “Until 1850, this style, inspired by the fresco technique, was tremendously popular in the foothills of the Alps, from Arlberg to Salzburg,” Rieger says about the profane art style with its sacral motifs.

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.” Rieger also paints maypoles with traditional patterns and pictures, one example being the famous maypole at the Munich Viktualienmarkt. “You can’t reinvent the wheel with Lüftlmalerei, though. It’s practiced the way it always has been, drawing inspiration from historic buildings.”

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.”

The beginning of alpine pop art

In recent years, Rieger needed to break away from the rigid images and patterns. And he did. Since then, he has been successful with his own distinctive interpretation of alpine art. One of his works was a large hotel facade in Garmisch. The sixty-square-meter (646-square-foot) fresco depicts a mountain-climbing scene—very modern, very abstract, very bright red. “It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist,” Rieger proclaims. “Then you don’t understand your calling.” His alpine pop art was born from this mindset. It’s a modern interpretation of the nostalgic, schmaltzy scenes from his parents’ and grandparents’ era, in jarring colors. The small-town conservatives declared him crazy for it. That didn’t bother him. No doubt Rieger remains a colorful character in the region, not least due to his appearance, distinctly reminiscent of a young King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

“It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist. Then you don’t understand your calling.”

Alpenterieur

When it comes to Europe's modern alpine art, there is no way around Rieger. This is also true of his interior designs. Since 2007, the artist has been uniquely reinterpreting alpine living under the label Alpenterieur. While his lines are modern, his rugged reclaimed surfaces tell legends of the past, like the lines on an old mountain farmer’s face.

He knows not everyone can afford the elaborate artisanal designs he creates from natural materials. That’s why he added affordable Alpen Kult Quadrate, made from reclaimed wood and felt, to his collection. “You can find them hanging in the quaint living rooms of old Garmisch ladies and the fanciest homes in Kitzbühel,” Rieger says. He’s already made thousands of the squares, not mass-produced but handmade—and he’s making more. He believes everyone should have a piece of his creativity. And his artistry is blossoming. Right now, he says, he senses a rush of emotions again like he did during puberty, a sign something new is on the horizon for him. What exactly it will be, he doesn’t know yet. But he imagines it will have something to do with ancient custom and tradition. The trend of modern design inspired by the simple mountain style of the past is growing. “Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated,” Rieger says. “Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”

This lifestyle trend is Rieger’s livelihood. But even more so, the Bavarian rebel walks the talk. His bohemian persona and alpine pop art certainly do marry the mountains and the valley, the pasture and the city. △

“Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated. Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”