Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Art Photography in the Shoemaker's Farmhouse

From the Photo Archives...

The shoemaker’s farmhouse in Alt-Riem near Munich was built in the 18th century. Stefan Höglmaier, founder of the Euroboden Group, bought the historical structure in 2013 and converted it into a a two-family house in collaboration with architect Peter Haimerl.

The architectural concept of the Stockerweg project is based on the premise of preserving the historical structure while innovating the space. The defining element is a concrete cube, rotated 45 degrees, that was inserted into the attic and extends along the entire length of the building. The design created surprising angles of light and shadow, old and new, concrete and wood...

Read our full story on architect Peter Haimerl—"The Soul Catcher."

As part of the Stockerweg project, Haimerl's wife, photographer Jutta Görlich, together with Edward Beierle captured the transformation during construction through artistic photography. At the time, the result was showcased in the photo exhibition „Verweile doch!“ (stay a while!) in the Architekturgalerie München. Here, some phenomenal images from our photo archives...

"Verweile Doch!"

Hillside Holidays

Near the Austrian border in Germany’s Allgäu, Haus P by Yonder boldly reinterprets the region’s traditional mountain architecture

Nestled into the hilly landscape of Southern Germany’s Allgäu, Haus P by Studio Yonder für Architektur und Design is a holiday home for a family of seven from Hamburg. The irregular shaped structure with a traditional 16-degree roof pitch embodies a thoroughgoing reinterpretation of the region’s farmhouse vernacular.

The supporting base of the 249-square-meter (2680-square-foot) home is made of core-insulated, exposed concrete. Above, black charred timber siding offsets the concrete and the gentle landscape. Clean lines and distinct angles are the dominant features of the home’s geometric design. The home comprises two separate buildings—the living area and a storage shed—united by a sheltered central courtyard, where the entrance is located. The orientation of the buildings lends privacy for the family while spending time outdoors.

Spaces

Open and bright, the interior has a harmonious flow of natural light wood and a wall of picture windows extending from floor to ceiling. These windows allow for majestic views of the mountain landscape.

The main level flows from room to room with no interruption except a wrap-around fireplace marking the beginning of the living and dining area off of the kitchen. The fireplace gives a feeling of warmth from every area on the main level.

An open staircase, which juts out of the side of the building to covers the exterior stairway beneath, ascends to the loft—simple in design, yet functional—above the kitchen. This is an area made to relax, unwind, and take in more of the surroundings, with deep-set ceiling windows letting in light and starry night views.

Set in the concrete base, the spacious lower level has two private bedrooms, a bathroom, and a sauna. △

Recipe: Germknödel with Plum Filling

An Austrian ski hut favorite by Austrian top chef Martin Reiter of Hotel Kitzhof in Kitzbühl, Tyrol

Germknödel are a classic lunch favorite at ski huts in the Austrian alps. The fluffy, steamed yeast dumplings are so filling, this comfort food can be a main dish all on their own. The traditional filling is Powidl (a thick spiced plum mousse), which can easily be substituted with plum jam. Germknödel are topped with melted butter and a generous heaping of a mixture of ground poppy seeds and powdered sugar. Recipe by Austrian top chef Martin Reiter, Hotel Kitzhof, Kitzbühl,Tyrol

INGREDIENTS

Makes 6 Germknödel

250 gr flour, divide 15 gr fresh yeast 25 gr butter, softened 1/8 liter warm milk 25 gr powdered sugar 2 egg yolks 1 tsp vanilla sugar (if you can’t get the little sachets, substitute with 1 tsp sugar mixed with 1/4 tsp vanilla extract) lemon zest a dash of salt 6 tbsp plum jam for filling

Topping

90 gr melted butter 90 gr ground poppy 50 gr powdered sugar

STEPS

Dissolve yeast in warm milk, stir in 50 gr of the flour, then sprinkle some flour on top, cover, and let rest in a warm place. This is called the Dampfl.

Heat water in double boiler pot set.

Add softened butter, powdered sugar, vanilla sugar, egg yolk, lemon zest, and salt into double boiler and beat until foamy and warm.

Knead Dampfl with the remaining flour and butter mixture into a smooth dough.

Divide dough into 6 parts, form balls, cover with cloth, and let rest for 30 minutes.

Once the dough has risen, flatten each ball and set 1 tbsp plum jam in the middle. Fold edges up and pinch together so dough closes around the plum filling. Set on floured surface with pinched closure facing down, cover with cloth, and let rest once more until dumplings have risen by half of their volume.

Meanwhile, bring water to a simmer in large pot.

Carefully drop dumplings in the water and simmer for 15 minutes with the pot lid half on, flipping the dumplings over half way through.

Meanwhile, mix ground poppy seeds and powdered sugar for topping.

Place each hot dumpling on a plate and top with melted butter and poppy seed/powdered sugar mixture (the locals heap it on).

For a less traditional yet heavenly delicious variation, top Germknödel with warm vanilla sauce instead of the melted butter, sprinkle with poppy seeds and sugar.

An Guadn!

Alpine Modern Holidays

Alpine Modern editor in chief Sandra Henderson shares her guide to a Bavarian-Coloradan Holiday

This holiday season, Dwell is handing over the mic to some of their publishers on the new Dwell.com. We are tremendously thrilled that our editor in chief, Sandra Henderson, got to share her favorite picks for the season with the Dwell community—and now we are sharing them with you.

This holiday season, Dwell is handing over the mic to some of their publishers on the new Dwell.com. We are tremendously thrilled that our editor in chief, Sandra Henderson, got to share her favorite picks for the season with the Dwell community—and now we are sharing them with you.

Our editor's Guide to a Bavarian-Coloradan Season

I grew up in Bavaria, hiking, skiing, and loving the Alps. With masters degree in political science and sociology in my pocket, I began my journalistic career at a German women’s magazine. On a trip to Washington, DC, I fell in love with my now-husband and eventually moved to the US. I began dreaming about starting a magazine that combines my two passions: modern architecture and the mountains. Meanwhile, living in Colorado, I serendipitously connected with Lon McGowan, an entrepreneur who at the time already owned an impeccably curated design shop in Boulder and shared my vision for a similar publication. Three short months later, we launched Alpine Modern magazine. We printed six beautiful issues before taking our content entirely online.

"Being a minimalist, I love to give beautiful things that are also useful and wearable—or are a treat to eat or drink."

Give

Three Peak Mountain Pillow for $75 from Alpine Modern—Hug a mountain! The handcrafted cushions—inspired by the maker’s yearly summer trips to Bend, Oregon and Three Sisters Wilderness—add a whimsical touch, whether you live in a mountain cabin or an urban condo.

Glerups felt ankle boots for $125—Because you can’t get cozy when your feet are cold. These warm felt house shoes are made of 100 percent pure natural wool and come in all sizes—from baby to grandpa.

Santal Woods Candle for $30 from Alpine Modern—Handmade in the USA, this soy candle fills my house with a wonderful smell of the woods. At the same time, the aroma is elevated and lovely for a festive dinner party.

Keep Cups for $24—For the busy body. Everyone already has a travel mug for on-the-go, but these cute and practical glass cups with lids are made for running up and down the stairs at home without spilling your morning coffee.

Drink

My favorite bubbly and bourbon to share with friends...

Meinklang Pinot Noir Frizzante Rosé from Austria for $18.99—You can pick this up from Whole Foods or order online.

Breckenridge Distillery Whiskey for $45.99—Make your mountainman happy with a bottle of Breckenridge Blend of Straight Bourbon Whiskeys. It’s made with Rocky Mountain snowmelt.

Listen

If on a Winter’s Night by Sting from Amazon for $11.23—The album is a stirring collection of earthy winter songs, with a couple originals composed by Sting. The others include folk songs, lullabies, and hymns from decades and centuries past that were recorded with friends and guest musicians. The haunting sounds transport you deep into a snowy forest. My favorite tune on the album is “Soul Cake,” a traditional English beggar’s song.

Want

On my own wish list this year...

Transcendent Mitts by Outdoor Research for $59—I trust nature’s wisdom, so I usually choose wool or down to keep me warm. These puffy mittens are blissfully light and pack down perfectly in a bag.

Gold Ear Conch Cuff by Loren Stewart from Goop for $285—The idea of wearing an ear cuff is so ‘80s—I know—but this minimalist luxe version, designed by Loren Stewart, is definitely happening now. Beautiful and sophisticated. No piercing required.

Go

Home for the Holidays! What’s a more magical place to be for the Holidays than Bavaria? Lela Rose, my 10-year-old daughter, has never seen my native Germany in winter. I am beyond excited she finally gets to experience the Christmas market in my romantic home town of Dinkelsbühl in December.

And finally—our tree? Always real, with a vintage hand-blown glass top.

Do you have any suggestions on what else you'd need to create a cozy alpine-inspired holiday? Let us know in the comments!

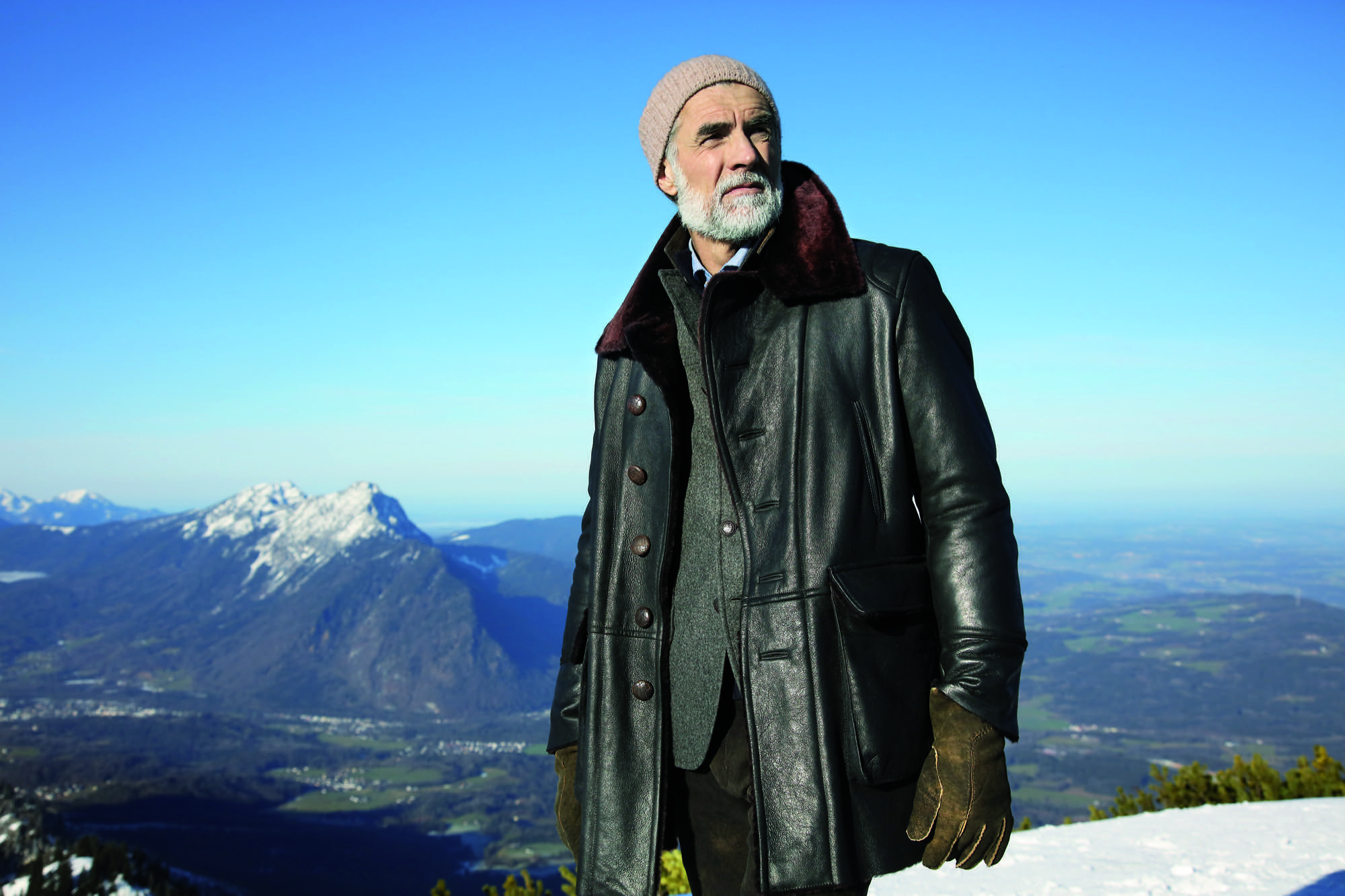

Traditionally Modern

At home with Markus Meindl, the modern mountain man behind Bavaria's traditional maker of lederhosen for the new alpine lifestyle between the forest and the city.

The luxury label Meindl—known for fine, handmade lederhosen—and its CEO, Markus Meindl, deftly move between alpine costumes and fashion, between city and country, between tradition and modernity.

When he was only eight years old, Markus Meindl stitched himself a leather satchel for school. In all likelihood, the result was extraordinary and made the young lad stand out among his classmates. Today, in his mid-forties, the head of Meindl Fashions continues to stand for new ideas, for modernism, for innovation, although or perhaps because he works—and lives—for one of Germany’s best-known companies of tradition.

The urban country home Meindl built for his family near the Austrian border reflects his desire to blend modern and traditional. The minimalist house primarily makes use of natural materials, such as wood and leather, but also a lot of glass and concrete, contrasting with the row of picturesque houses across the River Salzach, on the Austrian side.

The man’s fervent passion for craftsmanship and natural materials is also at the core of the Meindl brand. Along with its traditional lederhosen, the Bavarian family enterprise has long built a multifaceted portfolio of well-crafted leather garments.

The first Meindl lederhosen

It all began when Lukas Meindl, a local cobbler in the idyllic village of Kirchanschöring in Upper Bavaria, tailored his first pair of lederhosen in 1935. Even then, uncompromising quality and the highest form of handcraft were paramount, an art form. The name Meindl dates back even farther, to the year 1683, when Petrus Meindl was officially documented as shoemaker. Markus Meindl is particularly proud of the long family tradition. After he graduated from high school, trained as garment engineer, and apprenticed as couturier, young Meindl didn’t have to be asked twice to join the family company. On the contrary. “That has always been the matter of course for me,” Meindl says. “I practically grew up in the company and have developed a passion for leather material and leather garments at a young age.”

His zeal for creating something new comes from deep within. He has always wanted to develop products he loved himself. Father Hannes Meindl gave Markus the creative freedom and the space to let his youthful zest flourish. “If I’ve learned one thing from him, it’s his free-spiritedness. His honesty in working with the product. But also his honesty in leading his employees,” Meindl says of his father.

At age seventy-four, Hannes is still actively involved in the company wherever an extra hand is needed, whether that’s in sales, in production, or in design. The traditional embroidery, however, is Hannes’s favorite component. Meindl Fashions is famous for its chamois-tanned buckskin lederhosen with lavish hand-embroidered motifs, especially in the Alps, in Austria and southern Germany with their large festivals, such as the Oktoberfest in Munich. Up to sixty hours of manual labor go into handcrafting a pair of Meindl lederhosen. The work is partially done onsite by Meindl’s 120 employees and partially at production sites in nearby European countries, such as Hungary or Croatia. “Every product is designed by us; the know-how all resides in-house,” Markus Meindl says. “We have the most talented team here, the most expensive equipment, and, most importantly, the shortest distances.”

The advantages of in-house, local production are particularly valuable in the development of new products. The Meindl company has long expanded from singularly specializing in lederhosen—albeit traditional alpine costumes are currently experiencing a revival among all ages. “Lederhosen are not a trendy piece of fashion. They span the seasons and are not merely worn to folk festivals and special occasions,” Meindl says. “Lederhosen afford reliability and a sense of security. They rise above time and represent a symbol against calamitous mass production and the consumer society.”

The new alpine lifestyle

Meindl Fashions, with Meindl Jr. at the helm, embodies that pinpoint propensity for this sensibility, the longing for tradition, and for significance. Markus has helped establish the term “alpine lifestyle” in the European Alps; at the very least he has fueled it with products that can be worn on the mountain and in the city: high-quality leather jackets, blazers, sports coats, knickers. Twenty-four years old at the time, Meindl got his breakthrough in 1994 with the creation of a collection for the rebel folk singer-songwriter Hubert von Goisern. It charged the label, the entire fashion industry. A new, modern style conquered the world of traditional alpine garments and found a home at fashion shows like Bread & Butter in Berlin.

Meindl calls his style “authentic luxury”—his own language of design that derives from the combination of craftsmanship and tradition with modern fits and cuts. “Our products are authentic yet also luxurious, because they can never be mass-produced,” says Meindl. “Out of season” is Meindl’s motto. Transcending the seasons, Meindl garments can be worn in winter or on a cool summer night, adding value to each piece.

His message rings true in a fashion world that increasingly appreciates value, sustainability, and timelessness.

Nevertheless, few people really know how multifaceted Markus Meindl truly is. For instance, he designs and produces functional and innovative motorsports clothing in very limited editions for BMW. His leather jodhpurs are worn at the Spanish Riding School as well as by mounted police in Germany. His cousins run the local shoe manufactory, which makes quality mountain footwear and traditional costume shoes. A diverse product portfolio has always been the brand’s strength.

Country refuge for an urban mountain man

Quality stands above all. Timelessness, longevity—and Meindl sought to embody these values in the design and construction of his private home. “I’ve thought long and hard about how I want to design the house,” he says. “It was supposed to withstand time and still be as attractive twenty years from now as it is today.”

His friend Robert Blaschke of Raumbau Architekten in Salzburg, Austria, realized the project. Wood wherever you look, heated Swedish oak floors. Ceilings and walls are covered in 300-year-old oak wood reclaimed from Bavarian barns. The 3.9-meter-high (almost 13 feet) ceiling in the living room and the ceiling in the spa are lined in wooden cubes. The same element serves as armoire and shelving units in the living room and along the facade. The length of the pool—16.83 meters (55 feet)—reflects the year the Meindl company was born; a whimsical reference to tradition interrupted by modern elements. Tradition, lived modernly—that is Meindl’s philosophy. “I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things,” Meindl says. “But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time.”

“I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things. But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time."

Markus Meindl regards himself an “urban mountain man” who lives between the antithetical realms of an urban and a bucolic world. You work in the city during the week. And on weekends, you live in the mountains, where you go skiing, go hiking. “Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.” △

“Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.”

More from Meindl's collections...

Haus Z2 in Bayrischzell

The modern vacation home by Beer Bembé Dellinger reinterprets traditional Bavarian-alpine forms and materials

The large glass façade in the front and glass oriels on both sides of the house ensure a scenic view from the foot of the Wendelstein down to the valley from almost every room. The house's oblongness is inspired by the Alps and represents a reinterpretation of the characteristic traditional Bavarian barn. At the same time, the design concept addresses the site's narrow proportions.

The house's materials are also influenced by Bavarian-alpine traditions — mainly larchwood in form of tongue-and-groove boards for the façade and as shingles on the roof.

Lead architects were Felix Bembé (conception) and Michael Wondre (project leader and construction supervisor). △

Bavarian Rebel

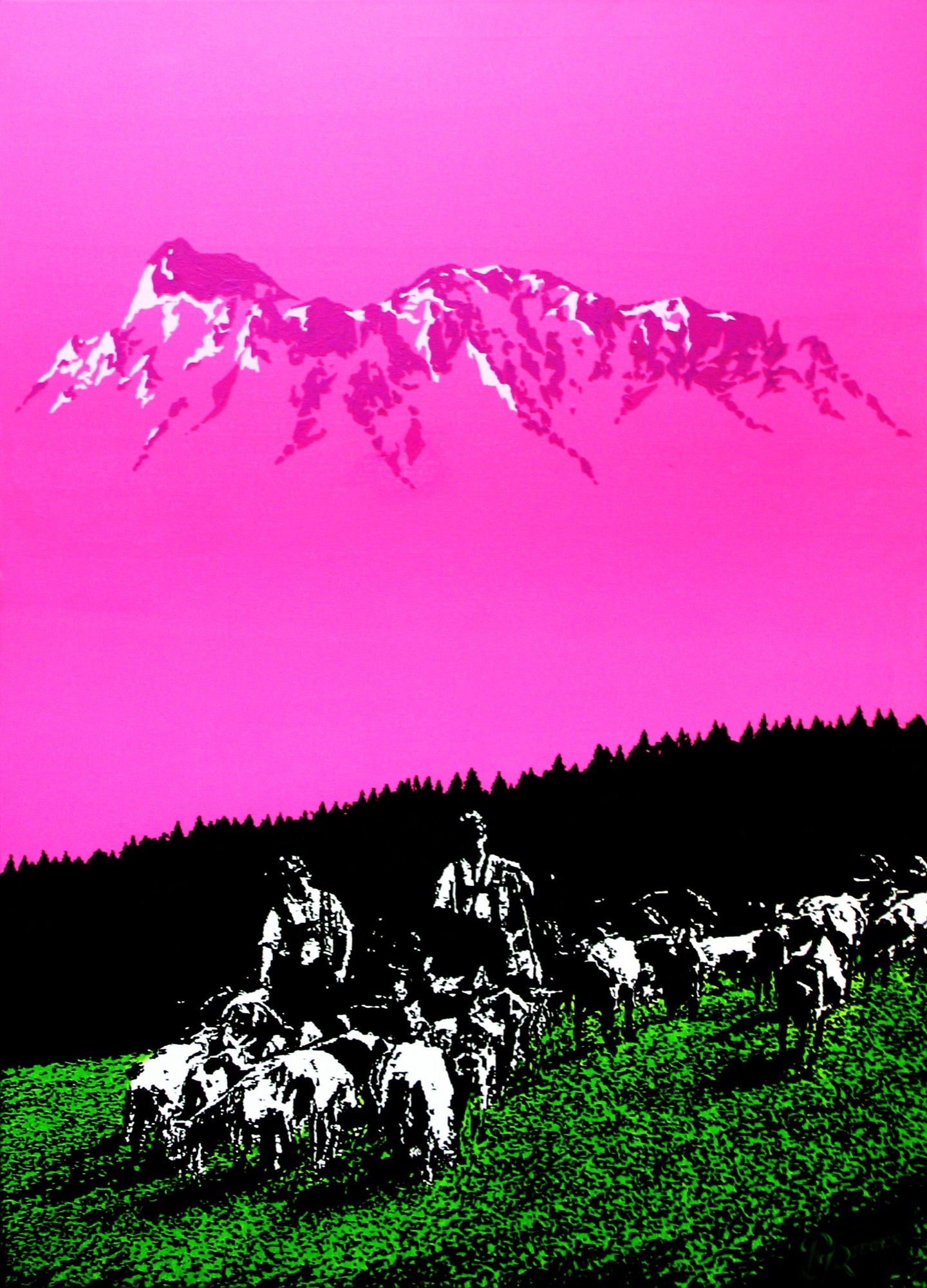

Avant-garde artist Bernhard Rieger — master of Lüftlmalerei, inventor of alpine pop art

A master of Lüftlmalerei, the traditional fresco technique characteristic of the Bavarian Alps, avant-garde artist Bernhard Rieger now revivifies authenticity with his invention of alpine pop art.

"Schau, wie die Sonn' aufgeht. Vom Berg ins Tal. Und von der Alm in die Stadt."

(Watch the sun rise. From the mountain to the valley. And from the pasture to the city.)

The artistic wunderkind

The funky music and the visuals on Bernhard Rieger’s website, alpenterieur.com [editor's note: for the best experience, open the link and listen to that intro beat and indigenous vernacular as you continue reading...], unmistakably manifest the Garmisch-Partenkirchen-based artist’s unusual style, which interweaves ancient tradition with modern design and sound to create something altogether original. The alpine electro beat he composed himself is just one example of the eccentric mountain rebel’s eclectic work. From his traditional Lüftlmalerei to alpine pop art to his modern designs with reclaimed wood, Rieger chooses a bold new approach to traditional art forms and materials. The man himself is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a walking paradigm of the young, wild generation of the European Alps.

Rieger’s website intro mixes original digital music—house, electro, lounge, and dump beats his musician friends composed—with acoustics like the cowbells he recorded in a pasture. The instrumentals are overlaid with his father’s voice speaking in the indigenous dialect of the Upper Isar Valley. The music, says Rieger, is his interpretation of the tightrope walk between cultural roots, modernity, and urbanization. He passionately philosophizes about society’s rekindled longing for regional culture and tradition. Rieger himself has never turned his back on the ancestral lifestyle. Growing up in the mountains surrounding the legendary tourist town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Upper Bavaria, he was deeply rooted to his native soil. He has never lost that authentic sense of life people now long for again.

Alpine minimalism

The idiosyncratic artist hails from a 400-year-old farmstead his parents lovingly restored and renovated in his childhood. Rieger’s father, a carpenter and sculptor who learned the trade at the Garmischer Schnitzschule (woodworking school of Garmisch), passed down his passion for South Tyrolean culture and style and for working with natural materials, wood in particular. Like his father, Bernhard Rieger is fascinated with the alpine farmers’ minimalist way of life, which continues to inspire him. Rieger grew up among folks who live by nature’s rules and rhythms. And even little Bernhard was blessed with a talent for painting.

“I painted gigantic murals with wooden pencils when I was only four years old,” Rieger remembers. Not to say that his affinity with local traditions has always been unshakable. As a youngster, he wore the baggiest jeans he could find and was more interested in his skateboard and punk rock than lederhosen and cowbell music. Nevertheless, he continued to express himself creatively throughout adolescence, whether it was through drawing tattoos and band logos for his classmates or designing skateboards and snowboards for himself and his buddies.

Flunking fine arts

He secured his first commissioned work at age fourteen. “I earned my first money designing certificates and painting wall murals,” Rieger recalls. What’s more, an odd job at a junkyard exposed him to old materials he took home to build lamps and other objects. After he graduated and completed his military service, Rieger was not accepted by the Akademie der Bildenden Künst München, where he wanted to study interior architecture. Instead, he trained as an interior designer and started his own business. “My unconventional style and my maverick projects were a thorn in the academy’s side,” Rieger reckons.

Lüftlmalerei

His original style fully flourished during that time. He practiced traditional Lüftlmalerei alongside his work as an interior designer. The large-format murals rooted in the Italian Renaissance first found their way to Bavaria via wealthy merchants in Augsburg who wanted their city houses adorned, and later they spread to the villages and the countryside. “Until 1850, this style, inspired by the fresco technique, was tremendously popular in the foothills of the Alps, from Arlberg to Salzburg,” Rieger says about the profane art style with its sacral motifs.

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.” Rieger also paints maypoles with traditional patterns and pictures, one example being the famous maypole at the Munich Viktualienmarkt. “You can’t reinvent the wheel with Lüftlmalerei, though. It’s practiced the way it always has been, drawing inspiration from historic buildings.”

“My work is my contribution to preserving and keeping alive our traditions.”

The beginning of alpine pop art

In recent years, Rieger needed to break away from the rigid images and patterns. And he did. Since then, he has been successful with his own distinctive interpretation of alpine art. One of his works was a large hotel facade in Garmisch. The sixty-square-meter (646-square-foot) fresco depicts a mountain-climbing scene—very modern, very abstract, very bright red. “It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist,” Rieger proclaims. “Then you don’t understand your calling.” His alpine pop art was born from this mindset. It’s a modern interpretation of the nostalgic, schmaltzy scenes from his parents’ and grandparents’ era, in jarring colors. The small-town conservatives declared him crazy for it. That didn’t bother him. No doubt Rieger remains a colorful character in the region, not least due to his appearance, distinctly reminiscent of a young King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

“It’s despairing if you don’t stir things up as an artist. Then you don’t understand your calling.”

Alpenterieur

When it comes to Europe's modern alpine art, there is no way around Rieger. This is also true of his interior designs. Since 2007, the artist has been uniquely reinterpreting alpine living under the label Alpenterieur. While his lines are modern, his rugged reclaimed surfaces tell legends of the past, like the lines on an old mountain farmer’s face.

He knows not everyone can afford the elaborate artisanal designs he creates from natural materials. That’s why he added affordable Alpen Kult Quadrate, made from reclaimed wood and felt, to his collection. “You can find them hanging in the quaint living rooms of old Garmisch ladies and the fanciest homes in Kitzbühel,” Rieger says. He’s already made thousands of the squares, not mass-produced but handmade—and he’s making more. He believes everyone should have a piece of his creativity. And his artistry is blossoming. Right now, he says, he senses a rush of emotions again like he did during puberty, a sign something new is on the horizon for him. What exactly it will be, he doesn’t know yet. But he imagines it will have something to do with ancient custom and tradition. The trend of modern design inspired by the simple mountain style of the past is growing. “Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated,” Rieger says. “Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”

This lifestyle trend is Rieger’s livelihood. But even more so, the Bavarian rebel walks the talk. His bohemian persona and alpine pop art certainly do marry the mountains and the valley, the pasture and the city. △

“Our parents thought of the traditional alpine style as old-fashioned and antiquated. Then the hype began a few years ago. Especially younger folks want everything to be more original and authentic and more sustainable.”

The Soul Catcher

Peter Haimerl's progressive designs save derelict farmhouses

Munich architect Peter Haimerl saves the old souls of derelict farmhouses through progressive design. Garnering the German architecture prize, his concept of inserting concrete cubes inside historic facades creates modern living spaces while preserving vernacular Bavarian architecture.

Cilli remained the last living soul in the old farmhouse built in 1840 in the Bavarian Forest. The farmer woman had inhabited the Waldler farm’s spartan living quarters at the edge of Viechtach, a small southern German town near the Czech border. When Cilli passed away in the 1970s, Peter Haimerl’s family inherited the historic farm, and young Peter resolved to someday save the building from deterioration—an endeavor that nearly two decades later would at first prove difficult for him. Haimerl had just graduated from architecture school in Munich in the early 1990s when, brimming with gusto, he ripped out the ceiling to create more space in the low-ceilinged parlor. “I interfered with the structure of the house by doing that,” Haimerl says in retrospect. “It became very clear to me that the houses here have a distinct character—that a house’s spirit lives on.” Wanting to preserve the soul of Cilli’s old farmhouse, he drafted close to 100 designs. It wasn’t until years later that Haimerl, by now a renowned architect, ventured into the actual restoration.

“It became very clear to me that the houses here have a distinct character— that a house’s spirit lives on.”

He soon discovered a hidden grid in the house’s structure; the proportions and dimensions themselves revealed a coherent picture. “To discover this took time. It appears the carpenters back then had an intuitive understanding of the framework. Many craftsmen and architects today, by contrast, are mere implementers of concepts from the home improvement store,” grouses Haimerl, who abhors Toscana-style mansions and, even more so, the romanticized yodel-cabin aesthetic often found in the Upper Bavarian and Austrian alpine regions. Fortuitously, he found himself in a particularly fitting area for his very personal project: The faraway, barren Bayerwald is miles removed from alpine kitsch and tourist hordes. In fact, the region suffers from rural exodus, since the young and educated are migrating to the cities. Country idyll meets slow decline here.

Out of stock

Many of the old houses and farms have already been torn down. Authentic historic design has become rare to find, the architect regrets. “Those were the homes of simple, poor people. They had to make do with the little they had, which characterizes the particular quality of construction.” Logs were treated rudimentarily, and artificial elements were reduced to a minimum. Haimerl is fascinated by this reduction to the essential, the individuality, the deftness of traditional Bayerwald architecture, which was soundly adapted to the given materials and setting. The old farmhouses were invariably built parallel to a geological phenomenon known as Bayerischer Pfahl, a quondam 150-kilometer- (93-mile-) long quartz vein traversing the northeastern Bavarian Forest. Ostensibly, the people in the region oriented themselves by the Pfahl.

His adoration for his native region and its peculiarities combined with his respect for traditional craftsmanship eventually drove Haimerl—who by now was practicing architecture in Munich—to entirely preserve the original exterior facade rather than “restoring the house to death,” as he phrases it. Instead, the new was to meet the old with prudence—a premise for all of Haimerl’s projects.

Set in time and concrete

Driving past the little chapel toward the forest, stately new construction projects and revamped farmhouses remain blatantly absent from the landscape. Time seemingly stands still here. Facades quietly crumble. Envisioning anyone living here is difficult.

In addition to the facade, Haimerl preserved the building’s underlying fundamental makeup—the stable in the house, the Austragskammer (a small room customarily reserved for a live-in aging relative) on the building’s north side, the granary in the attic, and the barn under a roof that extends all the way down to the ground. Haimerl poured four concrete cubes into the derelict farmhouse’s interior—lightweight concrete, to be exact, with aggregate foam-glass ballast. The foam-glass ballast, made from recycled glass bottles, is highly insulating and eco-friendly. The concrete dams the house from the inside while shielding it against the outside. The original facade remains intact; the ancestral farmhouse lives on. Haimerl received the Architekturpreis Beton (architecture prize, concrete) for this technique in 2008. Moreover, the vivid glass surface references the Bayerwald’s traditional glass industry.

The project’s realization proved challenging, since walls and ceilings had to be poured in one piece and the concrete needed to mold to the old masonry’s somewhat crooked plaster. The former Stube (parlor) is now the Mutter-Kubus (mother cube), the only heated space in the house. The three smaller cubes—bathroom, kitchen, and bedrooms—are heated by the fireplace in the great room. “We wanted the house to be comfortable, to an extent. But this wasn’t to be a house designed to serve us. The installations needed to be adequate for the old farmhouse and conducive to its time and scale,” Haimerl explains. Big openings in the concrete give view to the old facade, the old windows, and the attic. The large attic hatches are closed in winter and opened in summer for light and air. Parts of the old loam floor stayed exposed. Time and history are integrated within. “I want the patchwork character, those pieced-together elements of the existing building, to remain visible,” says Haimerl. “You have to be able to see the places where the house needed to expand, where it needed to grow with the needs of its inhabitants.” The building’s history is evident in the layers of peeling paint, the variation in the walls’ thickness that marks different building phases, in the antiquated electrical wiring, in the feed trough in the stable. Even the sparse interior design references the farmhouse’s ordinary past. The existing part of the building is furnished exclusively with pieces that were already there before the renovation, such as the old wooden bed that Cilli, the old farmer woman, slept in, and an old dress that still hangs in the closet—a patchwork of decades and a mirror of time, like the old farmhouse itself. Haimerl’s wife, Jutta Görlich, visualizes that sentiment in artful photographs.

“You have to be able to see the places where the house needed to expand, where it needed to grow with the needs of its inhabitants.”

The new living spaces inside the concrete cubes are furnished with salvaged artifacts and pieces made from recycled materials, such as reclaimed-wood benches and an iron stove built with recycled materials in the new kitchen. It’s comfortably warm in here, and the house’s old soul is perceivable. It’s easy to see why the architect loves to spend time in his idiosyncratic vacation home.

The farmhouse also serves as the architect’s office and showroom—here, he can demonstrate his design principles, his innovative mix of old and new. Something he continues to do. His project “Birg mich, Cilli!” (Salvage Me, Cilli!) received outstanding press coverage and raised great interest among city folks longing to escape to an authentic Bayerwald house. The project is equally recognized by the locals, who value the idea of preservative restoration. For that reason, Haimerl founded the interest group Hauspaten Bayerwald—loosely translated, “a call to adopt a Bayerwald house.” The initiative brings together builders, architects, investors, craftsmen, and grantors for the salvation of these relict houses.

Concert hall Blaibach

The movement has not only catalyzed the renovation of several historic farmhouses—and with that the architectural revitalization of the Bayerwald—it also connected Haimerl with the noted German baritone Thomas Eduard Bauer. The fellow Bayerwald natives collaborated in building a “refuge” for the Kulturwald festival Bauer had established to honor and celebrate the region’s culture. In a tenacious effort, and despite initial protest from the locals, the two contrarians created a strikingly innovative concert venue in the small neighboring community of Blaibach, where world-class musicians perform today. The building in the form of a tilted granite block partially sunken into the village square and outfitted with a granite gravel facade was largely funded through Bavarian government programs.

So, too, were the new community center and city hall next door: As part of the pilot project Ort Schafft Mitte (Place Creates Center) for the revitalization of abandoned village centers, Haimerl encased the existing building with a minimalist shell made from his recycled-glass concrete. The new concert hall he built was to evoke a sense of awakening in this somewhat desolate region. An open staircase beneath the monumental lithic structure leads into the foyer. From there, concertgoers reach the steeply ascending auditorium, which seats 200 guests on wire chairs. The slotted wall of cleverly stacked concrete slabs was entirely designed according to input from acousticians. On the outside, the tilted cube was clad with granite rubble, and many residents of the former quarrymen's village lent a hand. In 2015, the jury of the Deutscher Architekturpreis (the German architecture prize) distinguished Haimerl’s firm for the concert hall in Blaibach, among more than 150 submitted projects.

Haimerl x Euroboden

While the prestigious award was the highlight of his career so far, the unorthodox architect has no intention of stopping there. He recently completed his newest project—Verweile doch (Stay Awhile)—in collaboration with the construction and development firm Euroboden. In the Munich suburb of Riem, Haimerl applies the same preservation concept as with his Cilli project, without disregarding the peculiar characteristics of the town’s oldest estate.

Built circa 1750, the Zendath estate consists of a farmhouse and stables. Only parts of the residential portion and remnants of the stables were left standing, though. “With the historic farmhouse’s ambitious transformation, we wanted to create a pathbreaking paradigm for dealing with architectural heritage,” says Euroboden CEO Stefan Höglmaier. He and Haimerl intensively studied the rich history of the Schusterbauern house and its inhabitants (generations of owners were shoemakers and farmers) before embarking on their installation of two family-friendly dwellings. They connected the home and the stables spectacularly by inserting a concrete cube. Set into the forty-five-degree roof, the cube creates new levels with living spaces. Its steeply angled walls are a nod to the nearby alpine peaks. While the first unit remained largely intact except for a modern kitchen and bathroom, Haimerl’s design of the second unit encroached far more radically on the old structure. From the entryway behind the old barn door, multilevel mezzanines lead to a two-story space with gallery. Beyond lie the living room with a fireplace and the bedrooms. Exposed concrete, light-colored wood, and gray felt make up the interior architecture in this part of the building—only the old barn’s collar beams reveal that the centuries are overlapping here. “My architectural concept is based on two premises: preserving historic building stock while at the same time introducing a reinvention of space,” says Haimerl. He achieved just that in Riem. Once again, he saved the house’s soul through singularly progressive architecture. Once again, he caught that old soul and grandly made his mark with minimalist yet artistic aspiration to connect tradition with modernity. △

Monolog der Schusterbäuerin / Monologue of the Shoemaker Woman

1

es wird erzählt,

hinter dem Feldstadel,

ein kleines Häuschen

Dort wuchsen die Schuhe auf seinem Grund

*

it is said,

behind the barn,

there was a little house,

and there, the shoes grew out of the ground

2

es wird erzählt,

ihr Stubenboden war so sauber,

essen konnte man darauf

*

it is said,

her living room floor was so clean,

you could eat off it

3

es wird erzählt,

die Stallschwester Nanni spielte im Sommer unter dem Birnbaum ein Grammophon

Alle Knechte der Nachbarschaft kamen zum Hören

Sahen die wilden kleinen Früchte Tanzten wild in der großen Stube

*

it is said,

in summer the stable girl Nanni played a gramophone under the pear tree

All the servants in the neighborhood came to listen.

They saw the small, wild fruits and danced wildly in the big living room

4

es wird erzählt,

dass der ganze Zehent

der Kirche zu Riem zu reichen ist

in Geld

*

it is said,

that the whole tithe

had to be paid to the church of Riem

in money

5

es wird erzählt,

der Balthasar ging 24 Mal barfuß nach Altötting

Um 3 Uhr früh weg,

abends um 6 Uhr in Altötting

Ein braver Mann!

*

it is said,

that Balthasar went to Altötting barefoot 24 times

He left at 3 in the morning,

and was in Altötting at 6 in the evening

A brave man!

6

es wird erzählt,

die Schusterbauern haben sich verdient gemacht

im Dorf, für die Kirche

und gegen das Feuer

*

it is said,

the shoemakers rendered services to the church

in the village

And against fire

7

es wird erzählt,

mit dem Flughafen verschwanden die Felder,

da verschrieb sich der Schusterbauer

dem Pferdesport

*

it is said,

with the airport the fields disappeared,

so the shoemaker turned to

equestrian sports

8

es wird erzählt,

ein Lehrbub sollte von seiner Furchtsamkeit geheilt werden

In der Ledertruhe versteckte sich einer als Leiche

Man glaubte ihm nicht und nahm ihn bei den Ohren

*

it is said,

an apprentice lad needed to be cured of his fearfulness

Someone hid in the leather trunk pretending to be a corpse

He was not believed and was grabbed by the ears

9

es wird erzählt,

nach dem Brand der Scheune

verschwanden die Schusterbauern

von dieser Erde

*

it is said,

after the fire in the barn

the shoemakers disappeared

from this Earth

Peter Haimerl was born in 1961 in Viechtach, Bavaria. He studied architecture at the University of Applied Sciences Munich. After graduating in 1987, he worked for various architecture firms (1987–1988 for Günther Domenig, Vienna/ Graz; 1988 for Raimund Abraham, Vienna/New York; and 1988 for Klaus Kada Graz/Leibnitz). In 1991, he founded his own firm in Munich. Among his best-known projects are the remodel of Munich’s Salvator garage (2006), Das Schwarze Haus in Krailling (2006), “Birg mich, Cilli!” (2009), the concert hall in Blaibach (2014), and the restoration of the Schusterbauern farmhouse in Alt-Riem, Munich.

Haimerl received the Architekturpreis Beton in 2008, the Best Architects Award in gold in 2009, and the Bayerischen Kulturpreis (Bavarian culture prize) and the Deutschen Architekturpreis for his concert hall in Blaibach. Haimerl is married and has two children.

Room for Gemütlichkeit

The "Stube" — a special place in the alpine homes of Bavaria and Austria

In the Bavarian and Austrian Alps, a Stube is a gathering place to slow down for sustenance and storytelling. In the German-speaking mountain regions, the Stube has traditionally been and still is today the heart of an alpine home. The parlor. It’s where the family eats, socializes, solves problems, celebrates birthdays, raises children, laughs, and cries together. In this room, “family” in truth can morph into any iteration bonded by a chosen connectedness that trumps blood and wedding bands. Neighbors playing cards on a dark winter’s night. A knitting circle looping yarn in silence. A clique of youngsters bantering at one friend’s house before a night out around the village.

“The table is a meeting place, a gathering ground, the source of sustenance and nourishment, festivity, safety, and satisfaction. A person cooking is a person giving: Even the simplest food is a gift.”

— Laurie Colwin

The Stube typically has a large wooden table to gather around—such as this sublimely simple exemplar by Fraai Berlin—and a woodstove. The traditional seating setup is an L-shaped wooden bench built into the focal corner of the Stube. If the family celebrates the region’s inveterate traditions and customs of the prevalent Catholic religion, a carved Jesus Christ looks down over that table from his wooden cross high up in the nook the locals call Herrgottswinkel—God’s corner.

A namesake style of alpine folklore—sylvan songs accompanied often by zither and guitar—fills the Stube... Stubenmusik. △