Becoming JK

A studio visit with Colorado photographer and artist Jamie Kripke, who experiments with layers of images and color to create JK Editions.

Growing up in northwest Ohio, Jamie Kripke received mixed messages about making a career out of his love for photography. His mother, herself an artist, passed down her old Minolta camera to her son when he was fifteen. His father’s decision to buy a condo in Snowmass, Colorado, when Kripke was three jump-started a lifelong love affair with the mountains at a young age.

Kripke started snapping photos for the school newspaper at his Toledo high school. At the time, his mother’s 1973 Minolta XG-M with the macramé strap was “a gnarly camera to have for a kid,” he tells me. While his peers were playing with point-and-shoots with flashcubes or Kodak Instamatics, Kripke was teaching himself how to vary aperture and shutter speed for the perfect shot. He developed his own film and made prints in the school’s darkroom. His first published photo is a slim black-and-white of the high school football coach jogging toward the lens. And yet, Kripke put thoughts of pursuing a photography career out of his mind because “when you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

“When you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

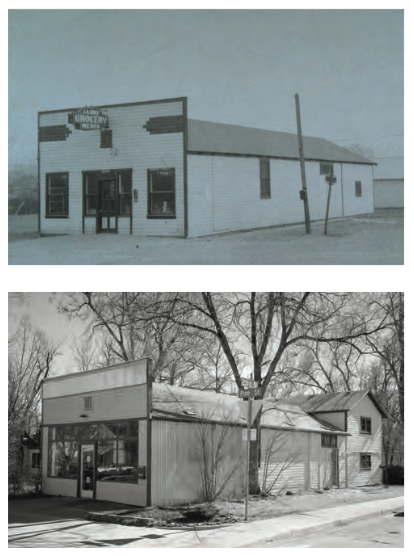

Today, Kripke is a professional photographer whose clients include Hewlett-Packard, Sony, Mini Cooper, and Visa. His editorial work has appeared in Dwell, Esquire, Outside, The New Yorker, Wired, and other publications. I join him at his Boulder, Colorado, studio on an unseasonably warm January day to learn more about his journey from high school newspaper photographer to successful independent artist. His corner studio has a deep history in the community, formerly operating as the local grocery, and before that, a horse stable. He’s been told that ghosts linger in the space. The white-walled studio is open and bright. We sit across from each other on facing vintage couches: mine a stormy gray with a mustard-yellow throw pillow, his a popping pink with a jade accent.

A simple white coffee table sits between us on a colorful striped rug. My eyes are drawn to a round clock hanging on the wall to my left; in place of numerals are songbirds—curiously, my own grandmother, mother, and aunts in Ohio all own one of these very clocks (my interviewee and I share the same home state). When I ask Kripke about the peculiar timepiece, he tells me that his father’s company in Toledo developed the original bird clock. “It has always been on the wall wherever I work as a reminder of my dad, his work ethic, and his business savvy,” he shares. Four mismatched desks of varying heights line the wall under the clock; there are no typical office chairs, but one desk has a short neon-orange children’s stool pulled up to it. The opposite wall is covered in framed black-and-white landscapes.

Kripke is a calm man; he sits cross-legged in jeans and a plaid shirt, answering my questions in a slow and intentional cadence. He explains that adventuring in the mountains of Colorado from a young age led him to the natural choice of moving to Boulder for college, where he dabbled in majors including pre-med and business before settling on philosophy. All those years, he was shooting photos with his old Minolta. In his bedroom back in Ohio, he had a poster of Bill Johnson, the downhill skier. He describes the image as a razor-sharp shot of the skier, airborne in a tuck and looking right into your eyes. As a kid, he’d often stare at the poster, wondering how on earth someone got that shot. On weekend ski trips to the mountains during college, he’d play around with photographing his friends:

“I was burning tons and tons of film to get one picture that didn’t suck.”

Kripke’s first breakthrough came a year or two after graduation, when Powder Magazine offered him seventy-five dollars for one of his images. This was a landmark moment in his photography journey; he recalls thinking, “Whoa, you can shoot pictures and get paid? That’s awesome.” The check and the letter from the magazine editor confirmed his deep longing to capture the world around him with his lens. He followed his curiosity to San Francisco, where he began assisting established studio photographers, a learning experience he likens to his graduate school. Spending much of his free time at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he began diving into the world of fine art.

Observing other photographers and artists led to a natural curiosity about their techniques and guided him in finding his own approach. “[Photographer William] Eggleston was one of the first guys to pay attention to everyday stuff and to the ugly stuff. All of a sudden, I fully grasped this idea that photos are everywhere around us all the time, and it’s a little overwhelming.” Kripke’s interest in composition was sparked by Stephen Shore, who had a “gift for finding these compositions where your eye follows the path through the image. For me it’s like a seven-course meal.” And Jeff Wall, a Vancouver-based photographer who spent an entire year constructing one photograph, inspired Kripke to make the move from “something you find that already exists to something that you create from scratch yourself—taking versus making.” If he wanted to get serious about photography, he knew he needed to be able to make.

One day, while living in California, Kripke saw an old car with a mattress tied onto the hood driving on the highway. He laughed out loud at the curious sight and instantly knew he wanted to re-create that scene in a photograph. He left a note on his neighbor’s station wagon, got an old mattress from a homeless shelter, and researched how to light a moving vehicle. “It was the first picture I really feel like I made, that I fully put all the pieces together.” He still keeps that photo in his portfolio, even though it is ten years old. He reflects on the elements he pulled together from his role models: Gregory Crewdson’s moody lighting, Robert Bechtle’s nostalgic subject matter, Stephen Shore’s composition. “In some ways this picture encapsulated all this stuff that I had been paying attention to up until that moment, and I was lucky to be able to turn it into a single image.”

The plunge

All the while, Kripke still had one foot in and one foot out of photography as a profession. “There are different stages of commitment. There’s the first stage where you think, ‘Hey, maybe I should try this.’ But there’s another stage, much farther down the road, when you have to be really serious and make a real commitment to not turn back.” While working as an assistant to other photographers in his twenties, Kripke had a paycheck to count on. But could he build a viable career on his own? Unsure, he met with a career counselor when he was around the age of thirty. “I was at a point where it was time to decide,” he remembers. That’s when he got the push he needed: “The career counselor asked me what’s been the longest relationship I’ve ever been in, and I said, ‘About a year.’ Then she asked me how long I had been taking pictures, and I said, ‘Since I was fifteen, so fifteen years.’ And she looked at me and said, ‘It’s time to get married, Jamie—to photography.’ That was the moment I knew it was time to go all in—not look back.”

Kripke decided to make the leap and commit to supporting himself with his craft, so he continued to self-educate by following his curiosity and seeking out teachers. He took photography trips. He drove a VW Bus around Europe in 2004, chasing inspiration until the van broke down, stranding him in the “Des Moines of Spain,” which provided new photography challenges for a long three weeks. Back in the States, he traveled to Santa Fe to study with Dan Winters, a portrait photographer whose work Kripke first saw in The New York Times Magazine. Finding an agent in San Francisco allowed him the flexibility to move back to Boulder. He now lives a block away from his studio with his wife, Kate, a psychotherapist, and his two daughters: nine-year-old Kinley (nicknamed “Nugget”) and six-year-old Bridger (aka “Hot Sauce”).

When I ask Kripke about his favorite creative project, he laughs: “Am I allowed to say Alpine Modern?” In addition to cover art and a black-and-white photo essay—“Alps // 40”— Kripke’s fine art photography series “JK Editions” has been featured in our printed magazine, issues 03 through 06. “I’ve really loved creating these landscapes for Alpine Modern because it brings together so many things that I enjoy—skiing, photography, art, being outside, exploring, creativity.” Kripke has come to the Rocky Mountains since he was three, and now as a Colorado resident, the alpine landscape continues to inspire his art: “The mountains are like my sanctuary. The mountains are where I go to recharge and be inspired and to exercise and to push myself and to build friendships and to scare myself. They offer so many ways to make us better people—or make me a better person.”

Color connections

The JK Editions use layers of photography, art-driven references, and color. Kripke begins each project by photographing architecture or landscapes. Back at the studio, he zeros in on what captured his attention in the first place and layers these elements with color: “We have emotional connections to certain colors, so the color is about trying to create that connection.” We walk over to the desk, where Kripke shows me his recent work for Alpine Modern: He layered six or seven photos of the same landscape in different seasons one on top of the other to create one complex image. The winter and summer scenes are stitched together, artistically suggesting spring.

He describes the experience of displaying his work: “When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Some of the best advice Kripke has received as an artist is to “change up your inputs.” He continues to look beyond photography for inspiration, seeking out painting, sculpture, music, books, and podcasts to avoid stagnating in one medium. His work is a reflection of this: “I think inspiration comes from unlikely places or maybe the combination of two things that you didn’t expect to see together.” He seeks to make something new by combining photos and mediums to progress a project “somewhere it hadn’t been before.”

“When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Kripke’s philosophy on life? “Just be honest with yourself, and be honest about what makes you happy.” When I ask him if there is anything else he would like to share, he laughs: “Everything’s for sale.” △