Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Introducing Alpine Modern’s New Nordic-Alpine-Inspired Menu

With worldly Chef Ellory heading the kitchen, seasonal ingredients shine in simple, clean food at the Café

We recently introduced you to our new executive chef, Ellory Abels. After she had helped to grow the San Francisco catering company Green Heart Foods, the Texas native traveled the world in search of culinary inspirations. The Culinary Institute of America graduate visited eight countries, where she collected different spices and cooking traditions she now integrates into her own kitchen.

Upon returning from her culinary expedition, the outdoor enthusiast and passionate rock climber settled in Boulder, Colorado, where her incredible talent, serendipity, and (our) luck brought her into the Alpine Modern family.

We sat down with the worldly chef to talk about the much more elevated and seasonal menu she has created for the Alpine Modern Café in Boulder, Colorado.

Chef Ellory talks about Alpine Modern’s new Nordic-alpine menu

AM What’s essentially different about the new menu you have created for the Alpine Modern Café?

EA When I came to the Café, the food was very approachable but lacked a theme. I wanted to elevate the menu and make it seasonal. With a seasonal menu, you have fresher ingredients and can source them locally. As humans, we’re based on tradition and the themes of life and holidays. I feel that food and the ingredients are very much based on that, too.

A Nordic-inspired menu

AM How did you come up with this new approach for the Alpine Modern menu?

EA I brainstormed what Alpine Modern was as a brand, what the food represents to us, and what we wanted to show the customers to be our foundation. Then I came up with the theme of Nordic-alpine food, which is scary for a lot of people. When you say Nordic food, you think of pickled herring or just really gross dishes like that. So I was very cautious of saying that to people. But I thought of what Nordic food is to me. I made a list of seasonal ingredients and started to build a menu off that. With food trends happening right now and the health consciousness—and I myself really care about nutrition—I wanted to implement that more into the menu as well.

AM Why Nordic? Boulder doesn’t necessarily represent a Nordic culture or environment...

EA Nordic represents simple living and food. I mean, look and their menus. It’s very healthy. It’s very clean. It’s not overthought. And I wanted to show that in the food. So I don’t necessarily want to say it’s Nordic-style food, but it has these same things behind it. It’s inspired by the foods of Iceland, Norway, Finland…

AM What are key ingredients you have implemented for the new menu?

EA I am using fennel, beets, dill, water crests—and instead of herring I’m using trout, and making it more approachable in that way. Instead of creams, I’m using thick, Nordic-style yogurts. And lemons, I’m using lots of vibrant zests in the food. And on top of that, I’m making it more seasonal.

For example, our beet hummus on the winter menu will probably change to a carrot hummus in the spring. The menu will probably change four times a year.

With a healthy dose of Ellory...

AM The new menu is seasonal and Nordic-inspired. But what part of the new menu is quintessentially Ellory?

EA The twist of having what I would call nutritional, healthy hippie food intertwined into it. It goes with the Boulder theme. I worked in San Francisco before I came here, and I’ve been very health-oriented in the places I’ve worked. Greens are huge to me, so I’m trying to implement greens into almost every dish. And freshness and the vibrancy of colors. That’s very much me. The chia seed pudding, the quinoa porridge, the kale salad with avocado seeds... That’s very much me.

“Nordic represents simple living and food... I mean, look and their menus. It’s very healthy. It’s very clean. It’s not overthought. It’s inspired by the foods of Iceland, Norway, Finland…”

Behind the scenes

AM Now that we have an executive chef, a huge step up for Alpine Modern, and we have launched a new menu, what else has changed at the Café?

EA We’re focusing on making this not only an environment where people can come and get amazing food but also have amazing beverages that are special to the Café here. We’re creating monthly special beverages. Right now, for example, we have the Williamsburg and the matcha latte, and we’re going to have a Turmeric Latte soon.

AM Besides taking the menu to the next level, how does having you as an executive chef impact the Alpine Modern Café and the brand at large?

EA Having an executive chef here allows a lot more growth for Alpine Modern, for our food, and for the whole scene of the Café. It allows us to create a solid foundation and consistency and to implement new ways to eat and to be here at the Café. For example, we’re starting an event program, and we’re hoping to have live music in the summer and to do grill-out nights. There will be so much opportunity. And we are starting to implement grab-and-go food from the Café into our downtown location soon, at the Coffee Bar in our flagship retail store on Pearl Street here in Boulder.

We’re also working on baking our own pastries fresh every morning. Another new thing is that we are offering gluten-free items. We’re working with Kim and Jake’s Bakery, a local gluten-free bakery. We’re using their bread and cookies, so almost everything on the new menu now has a gluten-free option.

“Almost everything on the new menu now has a gluten-free option.”

AM What is currently the most popular item on the new menu?

EA The Quinoa Lentil Bowl. It’s also one of my favorites for sure. And the Chia Seed Pudding—people are really digging that.

AM What feedback are you getting about the new menu?

EA The Café staff are loving it, and the customers are really enjoying it, saying things like, ‘Wow, you guys really elevated the menu.’ And that’s exactly what we wanted to do. The menu is not complex, it’s very simple, it’s all approachable because we have such a diverse community here in Boulder. We serve families and college students and young professionals—and we really wanted this to be something where you can walk in, and anyone can find something on the menu.

Come for the food and drinks, stay to feel good

AM What are you hoping people come to the Café for?

EA I hope they come here to have their daily clean food, to eat food they really want and that they feel good for a while. And the same with their beverages—having amazing coffee that we really put a lot of time into finding and creating the best process with our ModBar. I hope our customers come in here and see that there is a lot of love and care put into everything—with our plating, with our presentation, and with our sourcing. △

“We really wanted this to be something where you can walk in, and anyone can find something on the menu.”

Introducing: Alpine Modern's Chef Ellory

After traveling the world for a year, our new executive chef brings Nordic-alpine flavors and tales from around the globe to the kitchen at Boulder’s Alpine Modern Café

Ellory Blair Abels jumped into the food industry at the age of fifteen, when she began working in restaurants. After studying her passion at The Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in New York City, she accepted her first position with a catering company in a holistic retreat center in Upstate New York. With expanding industry experience, however, came the feeling something was missing. So the Houston, Texas native, who grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, packed her bags and traveled to expand her horizon—and her palate. Through this journey, her philosophy about food, life, and the kind of person she aspired to be has evolved. Immersing herself in different ways of life and seeing different countries has opened her eyes to a whole new vision of food as a celebration of life and culture.

Upon returning, she started afresh in San Francisco, where she found her cooking match: Ellory joined the lovely Lisa Chatham in her personal cheffing business, which together they expanded into the catering company Green Heart Foods. Over the course of four years, the business grew from two people to fifty employees and a café. With two production kitchens and another in the making, helping to build Green Heart Foods was a life-changing experience for the young culinary talent.

Then, in 2015, Ellory made one of the hardest decisions she’s ever made—to leave behind what she knew in San Francisco and explore the unknown. Going after a lifelong dream, she once again packed her bags; this time not knowing when she would return. She bought a one-way ticket to Peru and traveled to eight different countries in one year.

Ellory has recently returned to the United States to begin her next adventure in Colorado, where she says she is “beyond excited to join the amazing family of Alpine Modern.” Now she can’t wait to share what she has learned and seen over the past year through her food at the Alpine Modern Café in Boulder.

A conversation with Alpine Modern Executive Chef Ellory Abels

AM Who are you, in a nutshell?

EA I am an opportunist. I’m always looking for ways to push the boundaries. I don’t like to live my life within the lines. I make my own rules and love to take risks. I am very curious and like to explore the questions of life. Besides that, I strive to live a simple life that’s not overly complicated. I take pride in surrounding myself with people I love and sharing memorable experiences with them.

AM Along your path, what experiences and encounters have made you who you are today?

EA Traveling! I have been lucky enough to have been able to travel pretty intensely from a very young age. Last year, I took a huge leap to leave the home I’ve made in San Francisco and explore the unknown. I decided to fulfill a lifelong dream of mine and travel longterm. I bought a one-way ticket to South America, with no plans other than to see all of the beauty the world has to offer. I explored eight different countries, two continents, and seven states in one year, collecting friends, stories, spices, and culinary techniques from every corner of the world.

It was the single most inspiring, eye-opening experience of my life and has shaped me as a person and as a chef. Traveling has definitely been my biggest teacher in life. The more I explore, the more my senses are awakened, and the more alive I feel.

“I explored eight different countries, two continents, and seven states in one year, collecting friends, stories, spices, and culinary techniques from every corner of the world.”

AM Share some of your childhood memories of food.

EA I grew up in a Jewish household where food was always the center of the event. My parents were amazing at exposing me to different ethnic foods from a very young age. Some of my favorite memories are cooking for the Jewish holidays and for Thanksgiving.

“I grew up in a Jewish household where food was always the center of the event.”

AM When and how did you know you wanted to become a chef?

From a young age, I was very determined to be an artist. I filled my spare time after school and my summers with a variety of art classes. My dream was to go to the Savannah College of Art and Design. Looking at the portfolio requirements to get in, however, I realized this was not what I wanted. I explored other ways to apply my creative ability. Food had always been a huge outlet for me. I grew up spending a lot of time cooking and experimenting in the kitchen with my dad. So I decided to put more effort into exploring the profession of food by working in different restaurants. After being involved in the food world for only a couple of months, it became very apparent that this was the path I wanted to take. Food is my own expression of art and is definitely my medium.

“Food is my own expression of art and is definitely my medium.”

AM Who taught you how to cook?

EA My dad. He inspired me from a very young age to get into the kitchen. He also grew up working in a kitchen for the family diner in New Jersey, called “Abels Diner.” The dinner served a mix of comfort food and Jewish specialties. Listening to the many stories he has about growing up in the dinner has always inspired me and made me want to be involved in food. Fun fact… Frank Sinatra was a busboy for my grandfather’s diner. True story!

AM Who is your culinary icon? What do you admire about her or him?

EA Yotam Ottolenghi. I love his approach to food. His style and flavor profiles are very similar to what I love to cook. Israeli food is also one of my favorite cuisines to cook, and his cookbook Jerusalem is by far one of my favorites.

AM What’s your favorite food, and what do you love about it?

EA Hmm, that’s such a hard question. It really depends on the season and what trip I recently came back from that inspired me. I’ve been cooking a lot of curries from my most recent trip to India. It’s been fun to experiment with a lot of spices I brought back and to try to master the art of Indian cooking. Besides that, my go-to food to cook is probably Israeli food. I just love the mix of flavors and textures.

AM What culinary traditions are your methods and recipes rooted in?

EA Exploring food while traveling has shown me a variety of traditions, methods, and recipes that I bring into my own kitchen. I cherish these experiences and try to recreate them in my own version and share them with others along with the stories behind them.

“Exploring food while traveling has shown me a variety of traditions, methods, and recipes that I bring into my own kitchen.”

AM What’s your definition of good food?

EA Clean, simple, colorful, thoughtful, lots of love!

AM How do you translate Alpine Modern’s ethos of “quiet design” into your work at the Café in Boulder?

EA The food I create for Alpine Modern is clean and simple. It’s not overthought and shows off so much more by letting the ingredients speak for themself.

AM What’s your vision for Alpine Modern’s culinary future?

EA We have lots of exciting plans that are in the development phase. We’re trying to expand the experience Alpine Modern shares with it’s customers and bring the community together. One of the big changes is that we are now renting out the Café during after-hours for private events.

AM What’s your favorite place in the world, and why?

EA Tough question, but I’ll have to say, even with all of the amazing places I have visited around the world, nothing will ever beat Yosemite. No matter how many times I go there for an adventure, that place gives me goosebumps and brings the biggest beaming smile to my face. It’s just pure magic.

“Even with all of the amazing places I have visited around the world, nothing will ever beat Yosemite… It’s just pure magic.”

AM What makes you happy?

EA I’ve learned it’s the simple things in life that bring me the most joy. Being surrounded by my family and friends and living an active lifestyle that gets me outside everyday is my happy place in life.

AM What are you working on these days?

EA Lot’s of different things. I’m getting in training mode for climbing season to really try to get after it this year. I’m also in the process of developing new recipes, lots that are inspired by my recent travels. Besides that, I’m really putting a lot of focus on sticking around the states this year and spending lots of time with my family and friends and my pup, Chalten. △

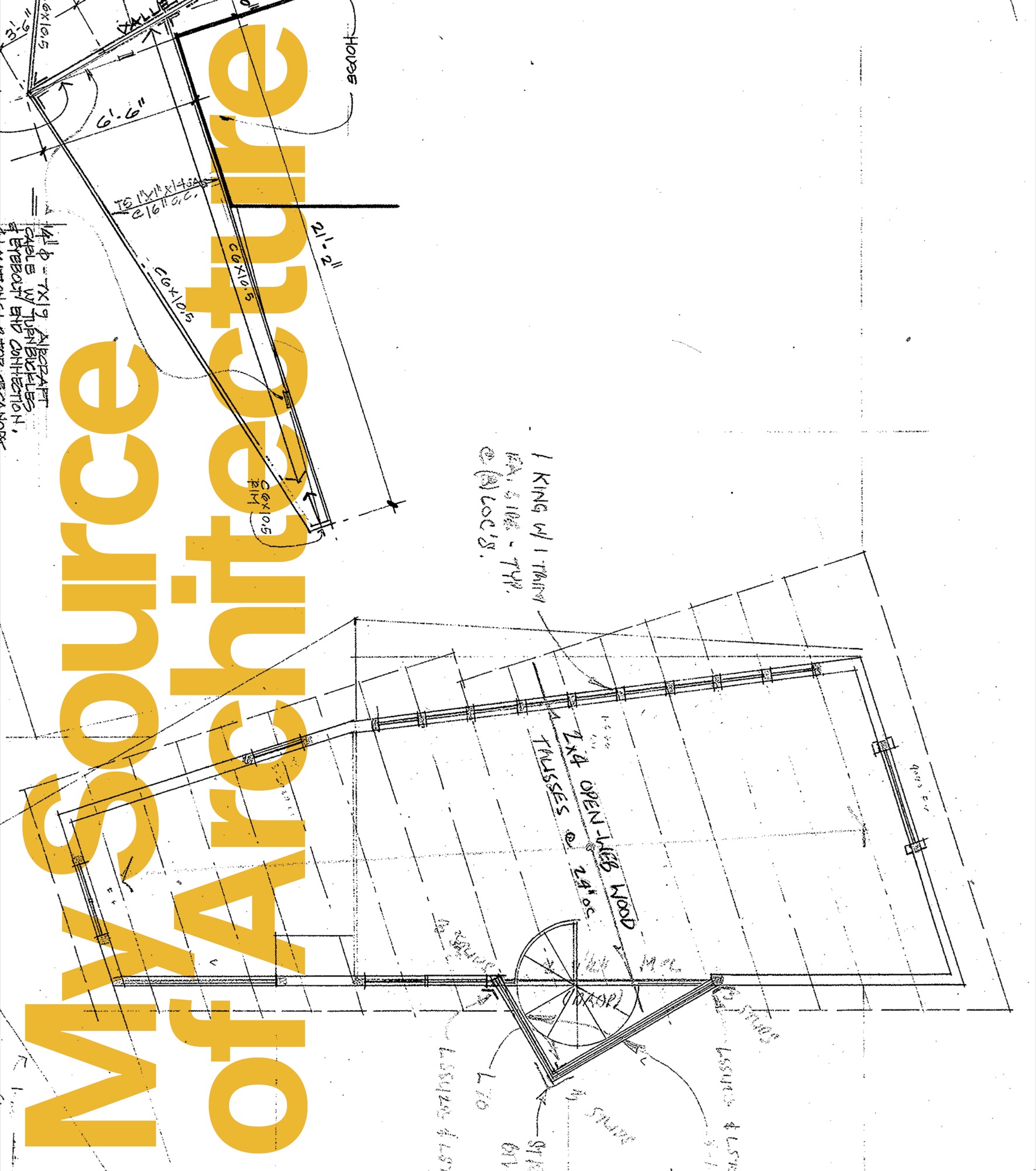

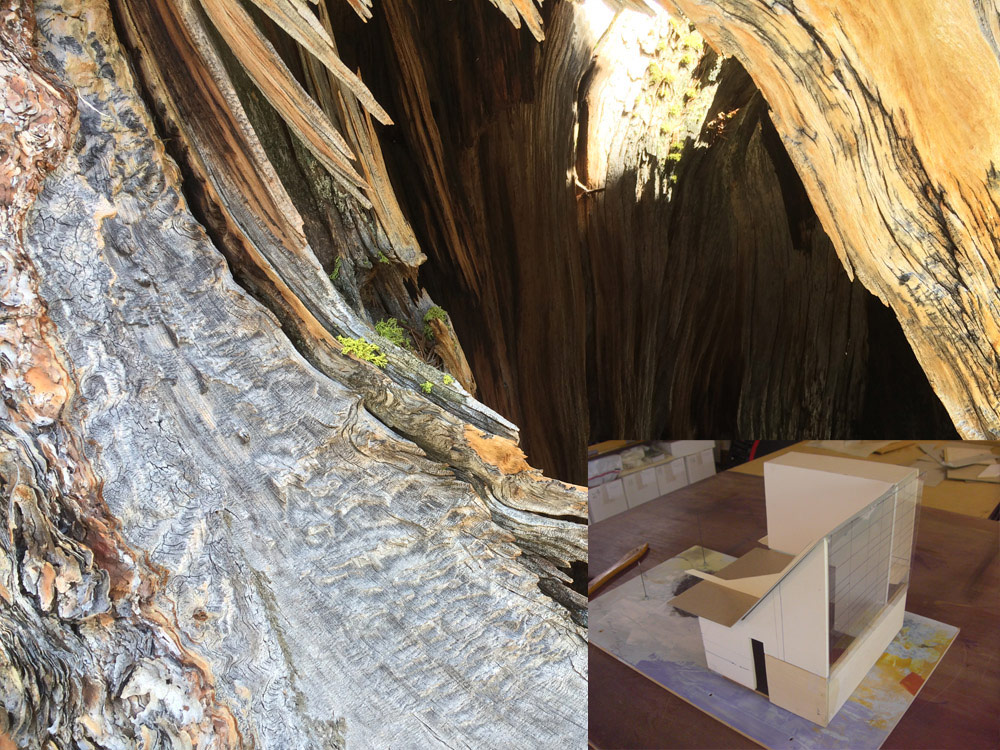

My Source of Architecture

A structural impossibility impels Colorado architect ml Robles to deconstruct her design and rethink the source of architecture. Surrendering to the house’s revelation ignites a deeper means to practice her métier.

Our finite world evaporates every single day as the dusk we have learned to overlook withdraws the light and dissolves form, transforming the day to night. The infinity that is our universe begins to appear, one star at a time, until the lid of our blue atmosphere evaporates and we enter the continuum within which everything exists. In this big picture, the earth holds its finite position for only a blink. In that blink, we build, but it is in the infinite continuum that architecture is sourced; from there a vibrating intelligence strikes our ideas with intuition and inspires our thinking.

This is why some places make us feel so profoundly alive. I seek those places, I want to stand in spaces that make me fall to my emotional knees, I want to feel light pulsing through my veins, I want to be so profoundly anchored in place that time stops and space expands. I want that here, now. To get that, as an architect, I must look directly into the source and accept those unnamable vibrations that ignite intuition and spark inspiration. I must be willing to step into the unexplainable and know it is undeniable.

The power of constructing

My exploration into the source of architecture begins with a small group of deer, three, maybe four, that stood puzzling at the edge of the upturned earth where the craggy foothills’ belly lay gouged open under the pure blue Colorado sky. Violent excavation into the land is the first in a chain of aggressions made when we build. I was stunned silent when I came upon that small herd of deer staring into the gaping hole where waving grass had clung just hours before. The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning. Watching those deer reconsider that site was burned deeply into my architectural thinking, for that is what we architects do: We alter what was. This realization was one of my first steps into the source of architecture: Respect what exists.

"The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning."

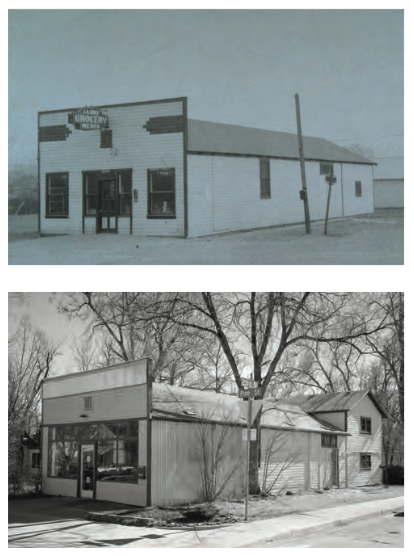

Working with what is

The small ranch house would have been a scrape-off to most sensible people. The builder and I, however, decided to work with the house and its detached garage, more from a perspective of “There is nothing wrong with its structure; let’s reuse it,” than any nod to its intrinsic qualities. The site was one of those hidden jewels in a nondescript part of Boulder, Colorado, that backed up to a parkway where the deep drainage ditch in front of the house made its way into a local watershed. Beyond that open area was a spectacularly clear view of the foothills curving along the horizon. I proceeded with designing a two-story, 3,500-square-foot (325-square-meter) house around, on top of, and including the existing ranch. It was all perfectly usual until the soils test, required to verify the capacity of the earth to carry the structural loads, said otherwise. The existing foundation would be unable to carry a second floor. The soils test is usually a nonevent, done for confirmation of what is already suspected rather than to dispute anything; this one, however, told us we needed a new foundation. We may as well have demolished the existing house since the newly recognized structural requirements were going to severely deconstruct the house.

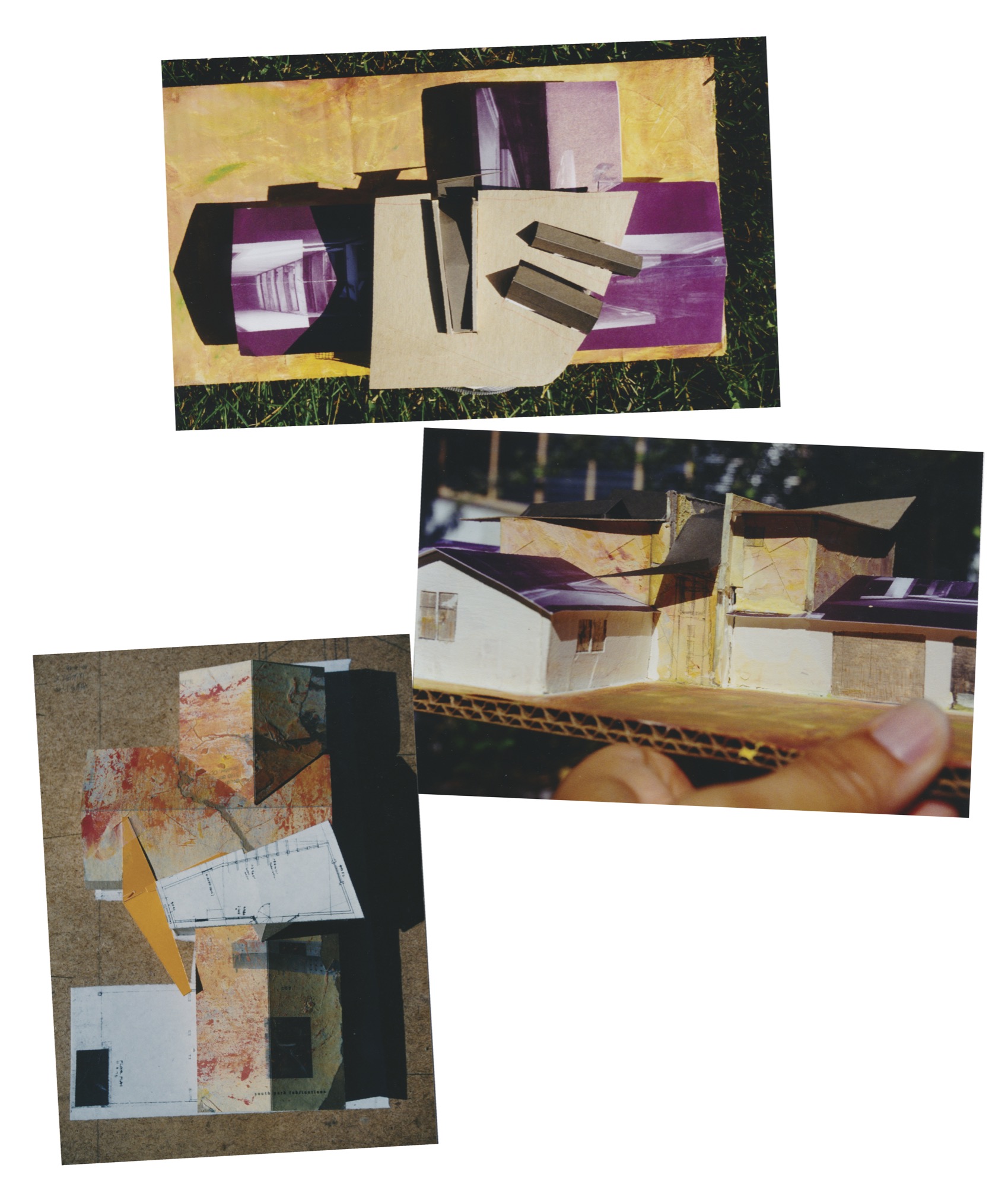

Going up

I sat with the cardboard model I had made of the house and garage. I had taped a collage of photos showing the magnificent view of the Flatirons—Boulder’s dramatic vertical rock-slab backdrop—onto the west edge of the model and was overcome by an insistence to build a second floor on that site to capture the view. Short of demolishing the existing house to build a proper foundation, I had to find another solution to going up. After wrangling with structural concepts, I sat down with my engineer and, using the model to illustrate, reasoned that if a tree could go up and out, why not a building? We would solve the problem by placing two piers between the house and garage to avoid disturbing the existing foundations, and then span back and front with steel beams to new foundation walls away from the existing structures. The framing spread over to the existing buildings, maintaining all the structural loads from the new construction to bear onto the two piers and new foundation walls. Like a gopher poking his head above the ground, the new two-story tower shot up from between the house and its garage structure with a spectacular 360-degree view.

We expanded the existing structure—both house and garage—to accommodate the new house with its tower shooting from the center. The only glitch was that the existing roof drained directly into the side of the new tower—a complete construction no-no, since the snow and rain draining off that roof into the side of the wall would eventually corrupt it. The standard way to deal with this is to build what is called a “cricket,” or hip roof, which is overframed on top of the existing roof at the wall intersection and stretches across it to lead water off to either side. This is what happens when construction creates a messy situation: The problem area is spirited away by trim false ceilings, overframing, and any number of other standard methods.

As I fiddled with that cricket roof on my model, imagining the tide of floodwaters raging against the tower wall, I became mesmerized by the idea of flowing water with its dancing light. What if we could experience that dancing light inside the house rather than scuttle it off the roof in obscurity? I was washed away with the inspired notion that we might be able to see this display of water.

What I resolved was to build a glass gutter—basically a slender inverted fold along that roof-wall intersection, furthermore sloping the whole thing to shed the water to the front of the house, right to the front door. I would capture the water in a big inverted wing that was anchored to the house roof on one side and flew into the sky on the other, creating a sheltering entry canopy. At the center seam, the low point of the inverted wing catching the water from the glass gutter, I sliced a gap and inserted a perforated sheet of weathering steel whose rust is managed in its composition. The rush of flowing water would fall through the perforations and drain into a gravel bed leading to the deep ditch along the front of the house. Mimicking nature, the water’s instinctive rush to the low point would be magnified, as in a waterfall with all its sparkling, glistening effect as it shoots to its destination. “You cannot build that,” they would say about the glass gutter. The big entry wing was less mystifying, and the weathering steel apparently not an issue at all as it was seen to be decoration.

Inspiration down the gutter (in a good way)

This would not be the first or last time I would hear those words, you cannot build that, but I could so clearly see the effect of the glass gutter on the inside of the house that there would be no turning back. Lucky for the house, the builder was also the owner, and he trusted the inspired gutter to deliver what was proposed. The house was built out with the kitchen spilling over into a dining area and outdoor patio and a living room with a face of windows articulating views of the Front Range—the eastern view of the Rockies. A see-through fireplace connected the living and dining rooms. Two bedrooms, a bathroom, and play area made the house family friendly. In the master suite, ceiling slots caught the glass-gutter reflections. A winding staircase led up to the tower room, which featured a sloping roof that jutted out to create shading overhangs for the wall of windows. We hosted an open house to celebrate the project and activated the glass gutter with a hose pouring onto the roof. Our “ship” launched with a cascade of water sheeting down the steel panel as the guests squealed with delight.

Over a decade later, I received an email from the latest owner of that house who had traced me through another house I had designed. This was the best house he had ever lived in, he wrote, and after living there, they discovered “wonderful, wonderful details,” such as the moonlight falling through the series of skylights.

When I read that note, I realized that I had never even considered the possibility of the moonlight casting onto that glass gutter and delivering itself through the ceiling slots. Astounding what shows up when unhindered inspiration leads to such unimaginable largesse. Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence.

"Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence."

Listen to what shows up

I have learned to embrace the marvelously unpredictable environment of design by working with physical models that take me out of my rational, calculating mind and drop me into an intuitive, three-dimensional state. Thanks to this project I got my second step into the source of architecture: Listen to what shows up. In this case the failed soils test and cricket roof changed what would have been an unremarkable construction into one that is able to lift the lid of our blue atmosphere and connect us to something so much bigger, something we might never have imagined, like the moonlight casting through the slots, awakening our senses and imaginations even more.

It is said that the dream is realized where the dream is sourced. If we do not dare to dream, to touch something within ourselves that ignites our passion, we will never see that dream realized. This certainly seems to be the case with places that make us feel fabulously alive—they touch something within us that we may have only known in dreams. And that is why, above all else, in the little blink we have on our finite earth, I am an architect. △

* * *

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently completing her first book in which she tells the story of how she came to be Under the Influence of Architecture.

Rugs and Furniture in Felt

A warm and fuzzy curation by Boulder interior designer Jennifer Rhode

Felt has a longer history than people may know. It is considered to be the oldest known woolen textile. The Sumerians have myths about its origins, and several felt shops were discovered in ancient Pompeii. Today, felt is being revived as a construction material for modern furniture and accessories that are inherently warm.

Rugs handmade in Iran

The felt of ancient Pompeii was created by matting and compressing wool fibers, and today’s felted rugs are produced in much the same way. The area rugs of Peace Industry are handmade in a workshop in Iran. The rugs are traditional in their time-honored production process, but the simple, geometric designs are thoroughly modern.

Braid pattern rug

The braided felt rugs of Angelo Rugs’ Highland Collection also celebrate heritage with the classical braid design, but the square, die-cut strand execution is crisp and fresh.

Colorful felt ball rugs

The felt ball rugs of Nepal resemble woolly marbles in a kaleidoscope of colors, stitched together. These whimsical rugs invite you to remove your shoes and engage.

Industrial felt rugs

Jim Zivic puts an industrial twist on both of his felt wool rug collections. For one, he attaches multiple colored felt panels with steel hinges, melding soft and mechanical. Zivic’s newest line features rugs created with felt strips linked together in random color ways, making each leather bound rug unique.

Die-cut bench

Felt is also being used to construct seating. The die-cut felt Joseph bench by Chris Ferebee is elegant in its simplicity, but exudes earnestness and warmth with its stacked, striped, woolen texture.

Felted chairs

The Felt Chairs by Ligne Roset are campy and sweet in their bright bubble gum colors, complemented by the clean, pared lines of the chair frame.

Coiled felt pouf

South African designer Ronel Jordaan’s Ndebele Chair is a circular, flexible seat created by stitching together a long felted wool coil. The serpentine design entices you to relax right into the center.

Felt stones

Stephanie Marin’s Living Stones are an unexpected contrast of soft, appealing textile and shape, depicting a natural element that is typically cold and hard. The stones beckon you to cuddle up and participate.

Felt Wall Art

The anodized, acoustic felt wall sculptures of Submaterial are creative collections of felt pieces arranged in colorful striped or geometric compositions—warm and modern.

Felted lamp shades

Outofstock’s pendant Stamp lamp and Tom Dixon’s Felt Floor Lamp surprise by using a thin layer of felt on their shades, providing both light and cozy comfort. Surely, the Sumerians would have appreciated such illumination when stamping out cuneiform on their clay tablets in the evening. △

Mountain Minimalism—The Next Level

Emerging Boulder artist and graphic designer Adam Sinda contemplates what’s next in Colorado’s art and design scene

Emerging Boulder artist and graphic designer Adam Sinda spends his days working at Made Movement, an ad agency in town. But the Colorado native also loves to paint in his free time and has created original art for two Alpine Modern t-shirts—which he personally modeled for us during a photoshoot set in our own alpine backyard. When he’s not designing or painting, the twenty-four year old loves to get out on the trails and run, alone.

We caught up with Sinda at the Alpine Modern Café to talk about Denver and Boulder’s art and design scene and how Alpine Modern is pushing the envelope on what defines Colorado.

A conversation with trail-running designer Adam Sinda

AM What’s your creative process?

AS Typically, I photograph outdoors; landscapes or anything I am inspired by. Then I bring it back to my room and try to simplify the form as much as possible—and add color. I’ve been working with color, lately.

AM What was your path to becoming a graphic designer?

AS I got a graphic design degree from Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, but I loved to take oil painting classes. That was probably my favorite art class. Design to me is so restricting, sometimes. And walking into an oil painting studio, you can just be yourself and experiment and play and get dirty. Most of my world is making stuff that’s going to be sold, and when I am painting, it’s for me.

AM Meanwhile, you are a graphic designer at Made Movement...

AS Yes, it’s an agency, and we work with brands like Lyft. Typically, we do everything from apps to web banners to illustration.

AM But you also do your own designs, and you have created art for Alpine Modern...

AS When I find a brand I can relate to and I want to be a part of, I jump in, anytime. I really feel Alpine Modern meets my ethics and aesthetics. I was working with photographer Garrett King, and we were just getting out there and going for hikes, just living in the moment.

AM You have designed two t-shirts for Alpine Modern. What makes that medium interesting to you?

AS The fact that other people are going to be wearing it and expressing themselves with it. Though they may never know who made that t-shirt.

AM What inspired those two particular designs?

AS For the Circular tee, what was inspiring me at the time was Alpine Modern’s Instagram. The motif is an abstract pulled from a photograph, and I started sketching and minimizing what I saw, just keeping it clean, simple, modern.

The second tee was the Typography t-shirt. It’s always fun to organize type in a particular way. I traded a mood board with the Alpine Modern team, and that shirt evolved from there.

AM What does it feel like to now see your shirts at the Alpine Modern Shop on Pearl Street?

AS It makes me feel good, happy. Mainly, it makes me feel like I am part of a culture that’s growing right now. A shirt is a simple thing. People build buildings, and people build houses. But sometimes it takes t-shirts and art to make you feel part of a culture. When you’re a developing artist, what you strive for every day is just to be heard, whatever medium it is.

“A shirt is a simple thing. People build buildings, and people build houses. But sometimes it takes t-shirts and art to make you feel part of a culture.”

AM What’s your message you want to be heard?

AS Wherever you are, when you are in a very attractive scenery in the mountains or in a landscape, you’re backpacking somewhere in the woods, take advantage of that moment and remember it because when times get rough, it is nice to pull from those images, and that’s what I would like to say, live in the moment when you feel it’s right. Take a mental photograph.

AM You say your Alpine Modern t-shirts makes you feel you are part of an emerging culture...

AS Right now you can see Denver developing this art culture. But to be honest, I think it is still refining what it wants to be. And Boulder has a huge opportunity to be a part of what downtown Denver is doing right now. And I think Alpine Modern can play into that world and really push the envelope on what Colorado is seen as. It’s cool to see Alpine Modern developing that image right now and really altering what artists are doing today.

AM Describe the Colorado art and design scene for someone from perhaps Berlin or Japan, who has never been here.

AS Art and design here is currently very minimal, very clean, but there are sparks of an identity evolving, and I think we are going to see a shift here. Clean and simple is fun, but what is the next level? What’s after that? Do we start developing some play with color or abstract forms? What’s that next shift? Because if everyone starts doing minimalism in Colorado, you will start seeing it get stale. I think in Colorado in general, we want to create a better culture, we need to spark something a little bit stronger, but I think we are still figuring out what that is.

AM Where will your next spark come from, building on that clean mountain minimalism?

AS Im really inspired by the 3D world right now. It’s fun to take these minimal objects and shapes and use 3D software programs to see behind them and see around them. A lot of designers these days just use Illustrator and very flat design. If you can design and know what’s behind objects, you start to see different light and that’s really interesting to me right now, so I’ve been experimenting with those programs.

AM What is the connection here to being in real landscapes and real nature? Hiking in the mountains is this quintessential three-dimensional experience because you do go behind the trees and behind the mountains and behind the next bend...

AS You’re spot on. When you’re out there with your friends, you’re moving towards an object and you’re reaching a goal. You are achieving something while you are hiking, going from A to B. And it’s fun to see how our designs are going to change with time. We have these VR headsets come out, and it’s gonna be fun to see how 3D plays into Colorado’s art culture. Colorado is such a good place to be right now as a graphic designer and an artist in general, and it’s just going to be even better.

AM What do you do when you are in the mountains?

AS I’m a huge runner. I used to compete in college, in the steeplechase. It has always been my escape. You just put on your running shoes and short shorts and get out the door and run. I love hiking, don’t get me wrong, but there is something cool about just going out and going for a jog by yourself for an hour and then come back and feel refreshed and ready to go. The cool thing about Boulder is you are really never that far away from a really sweet trail.

AM How has your love for the mountains influenced your design work?

AS Greatly. Growing up here and having lived here my whole life, seeing the mountains is comforting. And I think the they say a lot. △

A Winter’s Feast

Alpine Modern gathers a circle of friends and coworkers around the table in a chef’s beautiful Colorado home to celebrate life, food, and fellowship in the season of winter feasting.

The season of winter feasting creates a cornucopia of holidays: Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas, the Winter Solstice, Kwanzaa, the New Year, plus birthdays and anniversaries. These celebrations inspire us to gather friends and family together for a memorable meal. But these days, with our busy lives and family and friends often flung to the far corners of the world, getting a dozen people around your table for a dinner party can present a challenge—along with a measure of intimidation.

Menu planning, creating or finding the right recipes and foods, setting a beautiful table, cooking and timing the courses all require considerable skill and energy. Additionally, there’s a feeling of vulnerability—having people in your house, seeing how you live. Entertaining and orchestrating a special meal takes the host through the whole gamut of human emotions.

Flavors of entertaining

Entertaining has many faces. It can be simple, like soup and bread, or a sumptuous banquet. It can be planned months in advance or spontaneous and spur of the moment. There are as many styles of entertaining and hosting as there are personalities.

And that’s what creates the individual flavor and enjoyment of it—visiting someone’s unique home and seeing how they live, along with the types of food they like, their décor, artwork, and lifestyle. The best meals and get-togethers focus on togetherness rather than technique or perfection. Having guests help with some of the preparation sets the tone—even if it’s minimal like slicing the bread, tossing the salad, or helping to set the table.

The very human act of gathering

What is the true meaning of gathering and entertaining, really? Again, there are as many reasons and styles as there are days in the year.

Gathering to celebrate special occasions, birthdays, holidays, family, and community rituals may prompt us to investigate the practical, traditional, philosophic, spiritual—and perhaps even mystical—nature of entertaining and hospitality. What are some of the deeper primal undertones of this very human act of gathering together?

Dongzhi, or the Chinese Winter Solstice Festival, celebrates the coming of the cold weather and the return of the sun with feasting and festivities. Originating with the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220), the Winter Festival pays homage to the ancient yin and yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the cosmos. The philosophy holds that the yang, or muscular, positive energy, increases daily after the shortest day—so should be celebrated. Family get-togethers involve the making and eating of tangyuan, a sweet soup with balls of sticky rice, which symbolizes reunion.

Worldwide, changing seasons—the arrival of spring, midsummer, the autumn harvest, and especially the winter solstice—have historically been special times to celebrate and feast. Humankind has venerated the return of the sun’s light at the winter solstice throughout history and prehistory. Feasts have been held, and monuments have been painstakingly constructed and dedicated to it.

On a chilly night, we gathered for a winter feast that Colin and Sarah Kirby graciously hosted at their modern Boulder, Colorado, home to celebrate good food, camaraderie, and hospitality. According to Chef Colin, hospitality at its simplest is taking care of people, treating people well. The flavor of a host’s hospitality conveys a certain way of looking at the world, through food, drink, and its presentation.

"The flavor of a host’s hospitality conveys a certain way of looking at the world, through food, drink, and its presentation."

Perfect moments to remember

What happens when it all comes together? That moment when it all works really well? Reunion—as with the Chinese Dongzhi celebration. Communion. The creative and thoughtfully prepared meal is an emotional and spiritual experience. In addition to enjoying delicious food, guests feel a warm and deep appreciation for the host’s labors and generosity, and for each other. It’s truly a celebration and labor of love.

Some people, like our host, specifically design their homes with entertaining in mind. Colin’s cleverly repurposed and beautifully refinished Douglas fir floor joists–turned–dining table perfectly seats a dozen guests, as he intended. Set alongside an open kitchen, the broad table invites participation and observation.

As our host chef concludes, “Cooking is the only art form that engages all five senses.” And like any art form, an exquisitely conceived and executed meal inspires, elevates, educates, and enlivens.

In addition to the shared ritual of emotional and physical nourishment and sustenance, a special dinner or feast also offers the chance to learn about new foods and recipes, perhaps the favorites of the host. Special recipes from family or friends carry memories and significance, and enrich the experience of others who replicate them.

“Cooking is the only art form that engages all five senses.”

Recipes can hold special meanings for people, especially when passed down through generations or created for a unique event. Here, we are sharing some recipes our host, Colin Kirby, served at Alpine Modern’s Winter Feast that we hope will inspire you to take up the wooden spoon, start cooking, and gather some hungry souls around your table in celebration of togetherness. △

Recipes for a winter's feast

Tomato-Braised Leg of Lamb

The headliner. Braised in the oven for hours before your guests arrive, making this lamb dish will fill the house with a savory fragrance that will draw everyone into the kitchen. Go to recipe »

Braised Leeks with Black Truffle

An elegantly simple vegetable side for any festive dinner. Go to recipe »

The Alpine Glissade

Luscious Holiday libation: A festive cocktail based on cold-drip coffee. Go to recipe »

Introducing Jennifer Rhode

Our new interior design contributor will share her insights on creating an alpine-modern home

Meet Jennifer Rhode, a fresh voice on Alpine Modern Editorial. Based in Boulder, Colorado, the cosmopolitan interior designer and writer will regularly share her insights on making your home alpine modern through considered, quiet design. Her thoughtful narratives and approachable decorating tips will inspire you to move past the idea of “more” and focus on creating beautiful spaces with less. The California native will curate elevated styles and objects from the international world of design that embody functionality and quality craftsmanship.

At home with Jennifer

One sunny afternoon this fall, Jennifer invited me into her bright, modern home in North Boulder. We instantly bonded over raising fifth-graders and missing life in Europe. The petite brunette exudes a warm intelligence that at once makes you trustfully open your mind to what she has to show and tell you. The self-proclaimed “nester” surprised me with a delightful spread of fruit and cheese... and a dining table covered in notes and visuals on inspiring ideas for upcoming interior design stories and roundups, which we can’t wait to share with you—beginning next week with a collection of chunkily knitted home goods that are equally cozy and modern.

Jennifer Rhode’s design background

Jennifer began her career in fashion and wardrobe styling, working on television commercials and shows in New York City and then moving into window design in San Francisco. The mother of two has spent the last ten years working on interior spaces in San Francisco, Amsterdam, and Boulder. The designer draws inspiration from the many cities and environments she has lived in. She loves the dichotomy of mixing antique and modern, blank areas with pops of color, simple structures with a striking piece. And she always loves some whimsy thrown in. △

Title image: Interior design by Jennifer Rhode / Photo by Bob Carmichael

The Modern Craftswoman

Crafting small leather goods and wood objects in Boulder, Colorado, Alexa Allen is an artist, a designer, a maker, and a mother

Alexa Allen is an artist, a designer, a maker and a mother. Though not necessarily in that order. It’s more of a constant mash up of all of them, all at once, every minute of the day.

Her story is familiar in the world of design. She started one place, took a few turns, took a few more turns, and today straddles a beautiful line between working for a renowned creative house (i.e., superstar and jeweler to the stars Todd Reed), and launching her latest venture crafting small leather goods and wood objects.

Allen doesn’t turn towards the age-old cliches of “work hard,” “do what you love,” and “follow your dream,” when describing her journey. However, there is no doubt that this woman has put her heart and soul and blood, sweat and tears into creating a thriving business, that right now, after 20 years digging in, is on the cusp of something big.

A conversation with Boulder designer and maker Alexa Allen

Give us the 15 second version of how you landed where you are today

I’m originally from Boulder, and after living in California for many years, moved back to Colorado in 2010 to start a line of eco-modern children’s furniture. While my love for furniture and woodworking remained, I got the creative itch to branch out and learn another craft. I found a leather class by a very talented local leather artisan, and was hooked immediately. I quickly discovered that the combination of wood and leather goods was a natural fit and this realization has shaped my career path ever since.

"While my love for furniture and woodworking remained, I got the creative itch to branch out and learn another craft... I quickly discovered that the combination of wood and leather goods was a natural fit."

What aspect of your upbringing/childhood affected your decision to go into woodworking?

During my childhood, my father was a contractor so I spent a lot of time on construction sites. My father taught me about the tools of his trade—how to hold them correctly, how to use them, and how to take care of them. I spent endless hours trying to master the art of hammering a nail all the way in with one hit. I never did master that one. However, I’m sure I was one of the only girls in third grade who could wield a hammer, and I took great pride in it. Looking back, my career as a craftswoman makes complete sense though, truth be told, as a girl, I never envisioned that I would earn a living doing so.

"Looking back, my career as a craftswoman makes complete sense."

Describe the moment you decided to become a craftswoman

I earned a bachelor of arts degree in art history from Scripps College in Claremont, California. Scripps is an esteemed women’s college, and in addition to providing me with a great foundation in the arts, it also gave me the strength and confidence to succeed as an independent woman.

After my time at Scripps ended, I realized that interpreting and assessing the art of others was not my ultimate purpose in life. I wanted to create art of my own. As I contemplated which direction to take, it soon became clear that I needed to practice an art form that was physical and hands on. Thus, I enrolled in the furniture design department at The California College for the Arts (CCA). For me, the act of making/building/creating must engage both my mind and body—the physical act of making is a crucial component of my art.

"Scripps is an esteemed women’s college... it also gave me the strength and confidence to succeed as an independent woman."

Furniture-making has now evolved into leatherwork and I am excited to see where it takes me next. The more I learn, the more passionate I become and the more my creativity grows. This thirst for new skills is the driving force in my work. By continuing to learn and expand my skills, I can confidently call myself a designer, an artist and a craftswoman.

"By continuing to learn and expand my skills, I can confidently call myself a designer, an artist and a craftswoman."

What is the one piece of advice you would give to young women who are just getting started?

I was fresh out of art school at the California College for the Arts when I was hired at a custom cabinet shop in Oakland. The furniture department at CCA had a fairly large number of women in the program and we had an amazing camaraderie. It never occurred to me that this would not be the case in a “real life” scenario.

I was hired at the woodshop in the middle of a high-end Japanese-inspired project, which required a lot of skilled, on-site work. I was called on to route a 12-inch circle that needed to precisely fit a metal fixture, which had just been laid. I was stressed—one small slip of the router or one mistake in sizing, and I would have set the project back by weeks.

I made a jig and practiced in the shop, until it was perfect. The day I walked on site, there were five drywall guys all staring at me. I walked in and set up my router and my jig. By the time I had finished setting up the entire construction crew was watching my every move. I was so nervous! But, I knew what I was doing and I confident in my abilities. Needless to say I executed the task perfectly and from that day on, I was known as “the router queen.”

So my advice to women out there who are just getting started? Know your shit and walk in there like you own the place. △

This story was originally published by TARRA: Women Who Create

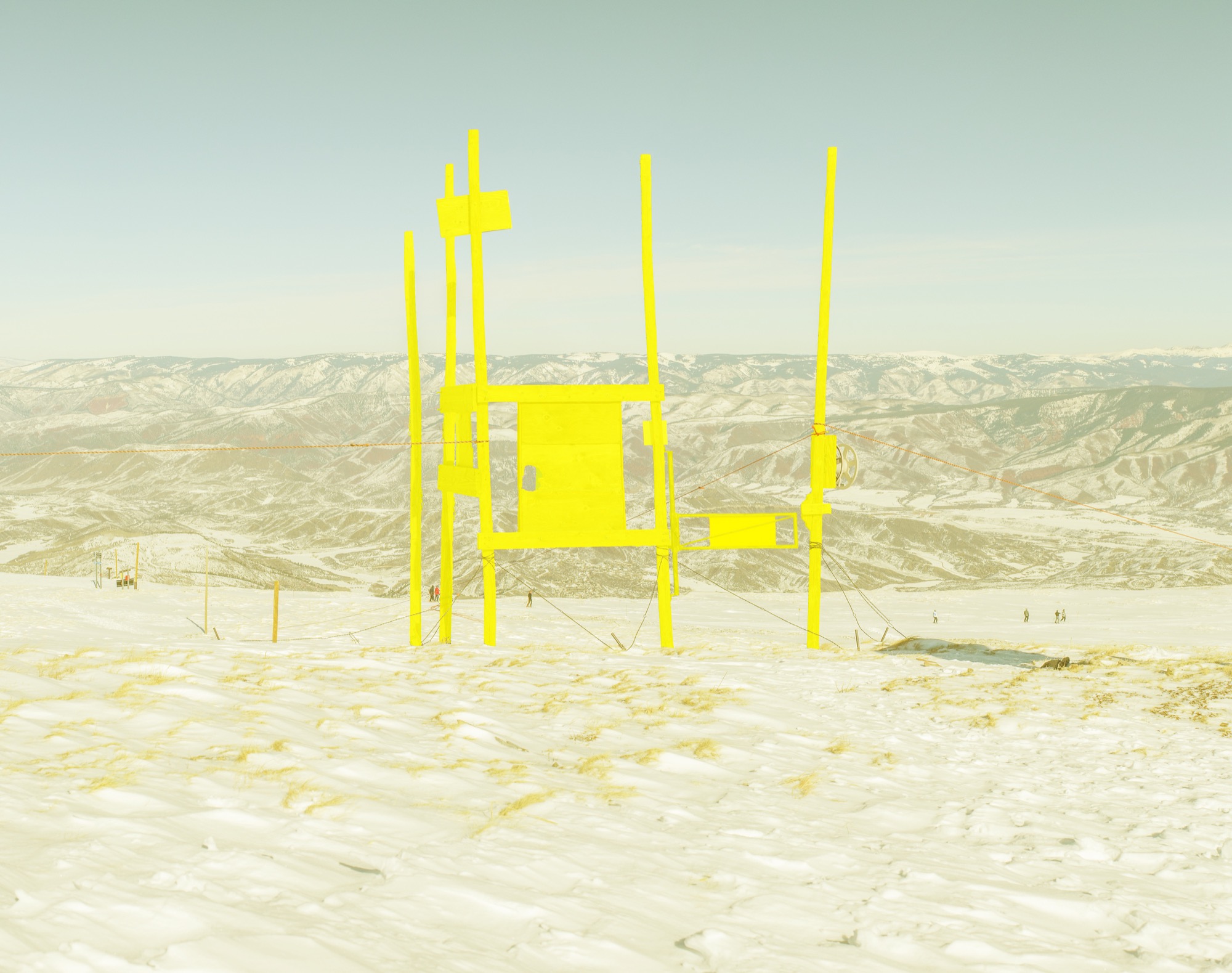

Alpine Modern + JK Editions: Fall

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints by Boulder photographer Jamie Kripke exclusive for Alpine Modern

Art Photography by Jamie Kripke A portfolio of images by Boulder, Colorado-based photographer Jamie Kripke, created exclusively for Alpine Modern. An ongoing project that studies our connection to the alpine landscape.

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints of these images are available to purchase through Alpine Modern.

The Nomad Behind the Lens

A conversation with photographer Garrett King, @shortstache on Instagram

Garrett King, a Colorado transplant from Texas, goes by the moniker “@shortstache” on Instagram. The name originates from a company he and a friend started after college, and while the company is no longer a part of King’s life, the tongue-in-cheek name remains and leads 119,000 followers to King’s photography.

King, more comfortable with anonymity than self-promotion or marketing, worked his way from a “weekend warrior” to a full-time photographer and shares his thoughts on the longevity of the field, as well as the community he’s creating through his work in collaboration with others. King’s work emphasizes perspective and playfulness of natural landscapes, while not sacrificing composition and contrast.

A conversation with Garrett King

What got you into photography?

I was born in Amarillo, Texas, and studied design and fine arts at Texas Tech and West Texas A&M. I mainly focused on videography, though, not photography. My friend and I started a company called “Shortstache” where we made short films about people in Texas who inspired us, like the oldest letter-presser in the state and a woman who made bicycles out of recycled materials.

Hence the name: @shortstache?

Right. At the time, we were competing in a mustache-growing contest, and it kind of stuck. Now it’s just me.

And then Instagram came along…

I joined Instagram about two years ago and never had the intention of using it as a platform to turn my photography into my career. I never intended to “make a name” for myself on Instagram. I would just respond back to everyone. They would respond; I would respond. It just kept going.

So it became a platform for community for you?

Exactly. I’ve met some of my best friends in the world through Instagram because we connected over a common goal or interest. I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram. It’s great because you can ask a question about a new place and get feedback almost immediately. Once, a few friends and I went to Portland, Oregon, and I posted that we didn’t have a car but would love to go around the city. Quickly, I got a message from a guy saying that he could be there in an hour, and I’ve been close friends with him ever since.

"I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram."

Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier. I’ve found a mutual respect pervades the community, and it’s been fun to see that come into fruition in my life and work.

"Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier."

How did you find yourself transitioning from videography and design to photography?

I’ve spent most of my working life designing. Photography was always an offshoot, a side hobby. It was interesting how things shifted: When I moved to Colorado two years ago, I quickly became a weekend warrior. I was leaving work at 5 p.m. on a Friday, driving until 2 a.m., camping and exploring and shooting wherever I could. I started posting my photos from these trips on Instagram, and, I guess, it sparked people’s interest.

Why camping and natural spaces in particular and not classic city shots or portraits?

I could only do the city thing for so long. You can get nightlife and restaurants in a lot of places, but, when I moved to Colorado, the mountains were in my backyard, and there was just so much to see and do. I found myself always escaping to the mountains to build stories or create memories. I will say, though, some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work.

"Some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work."

What has your focus been in developing your work?

For me, it’s always been about storytelling. You could consider me an adventure photographer, but the goal is always about capturing a moment. I want to continually get to the bare essentials and strip things down to the core. When I look at the bigger picture, I hope my work is inspiring and propelling me to see more and do more, while growing as a person. It is an extension of myself, after all. As it gets better, I want to get better. People are always asking me about what gear I use but it’s not really about gear; it’s about a developed style and whether you’re producing consistent and engaging work. I think you have to have the eyes and passion to discover good shots and you have to practice, practice, practice.

"It’s always been about storytelling."

Now that you’re a full time photographer, there must be a necessary separation between Instagram and work for you…

There definitely has to be. Anyone who asks me about their photography and how to make it big on the platform, I try to remind them that it’s a launching pad and business tool. I’ve had companies see my work through Instagram and invite me to shoot for them. It always goes back to the work. Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity. If you’re good and passionate, people will find you.

"Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity."

Any current projects?

Something I’ve been really excited about is a collaborative effort with other photographers I know, called @collectivenomads. We wanted to take creative people in different mediums and build each other up.

What do you want people to think when they stumble across your photography?

I hope they ultimately see that I’m a real person. Yeah, I want to have a consistent and built-up style, but I want people to see who I am, as a person who does the same stuff as them, and engage.

I never want my work to be dependent on a platform. I’m all about being on Instagram for the right reason: to know people and build relationships. It was never about free gear or “blowing up.” The dream was always to make my lifestyle I love into a paid job. I love design and want to continue to do that while also exploring my work as a photographer. △

Nature Is Architecture without Enclosure

Why Alpine Modern has a brief cameo in ml Robles' upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"

From my upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"...

So much of architecture is about replacing what exits. We remove buildings or parts of them, we scrape off land. We like new.

Then we get immensely attached to the buildings that have weathered throughout centuries. Think, Venice or historic buildings like Monticello or Westminster Cathedral. And we want to preserve them, not change a thing.

This is the discussion design enters into when we begin the critical examination of a project’s circumstances: What actually exists? Although the direction that is uncovered in the partí—the basic concept of an architectural design—holds both the physical and ephemeral, it is innumerate. Design, therefore, is a process of uncovering and illuminating the exact constructs necessary to meet the partí. And this is where the eye of the beholders produces the endless solutions to any given design problem. (Put another way, this is also where all hell breaks loose, for who is to say when a partí has been met?)

If architecture begins at the beginning of everything, and it is guided forth by secrets that cannot be told within the mind alone but are revealed by light, then it would seem that in order to uncover and illuminate the exact constructs necessary, design would have to continuously trace back to origin, to tapping the feeling that instantaneously shoots into the infinite.

There is an image on the farewell cover of Alpine Modern’s print magazine. It is an image that fades from a near-white mountain backdrop to a dark silhouette of a lone person in profile standing on a mossy green capped rock. I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure. △

"I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure."

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently writing her book "Under the Influence of Architecture."

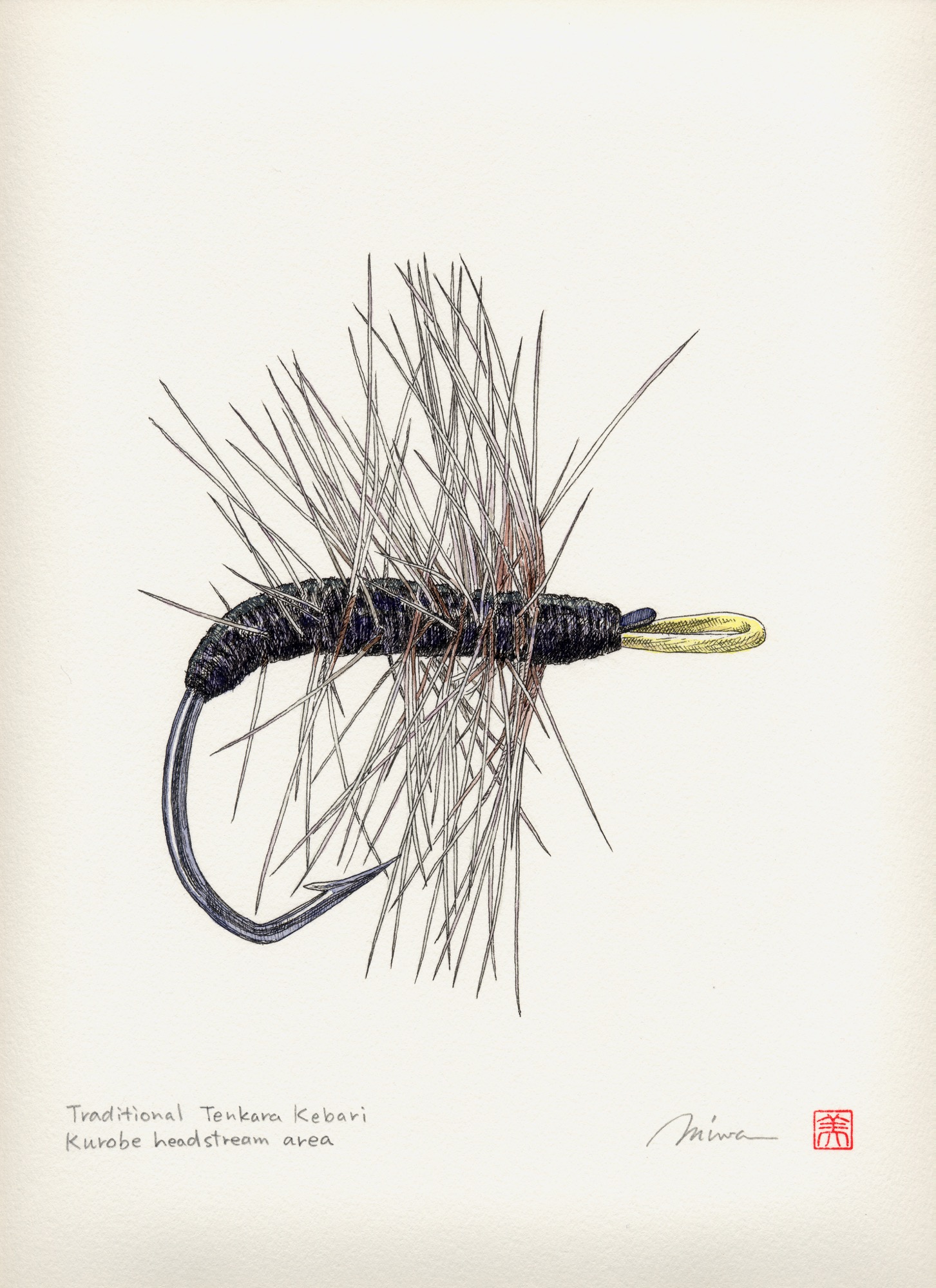

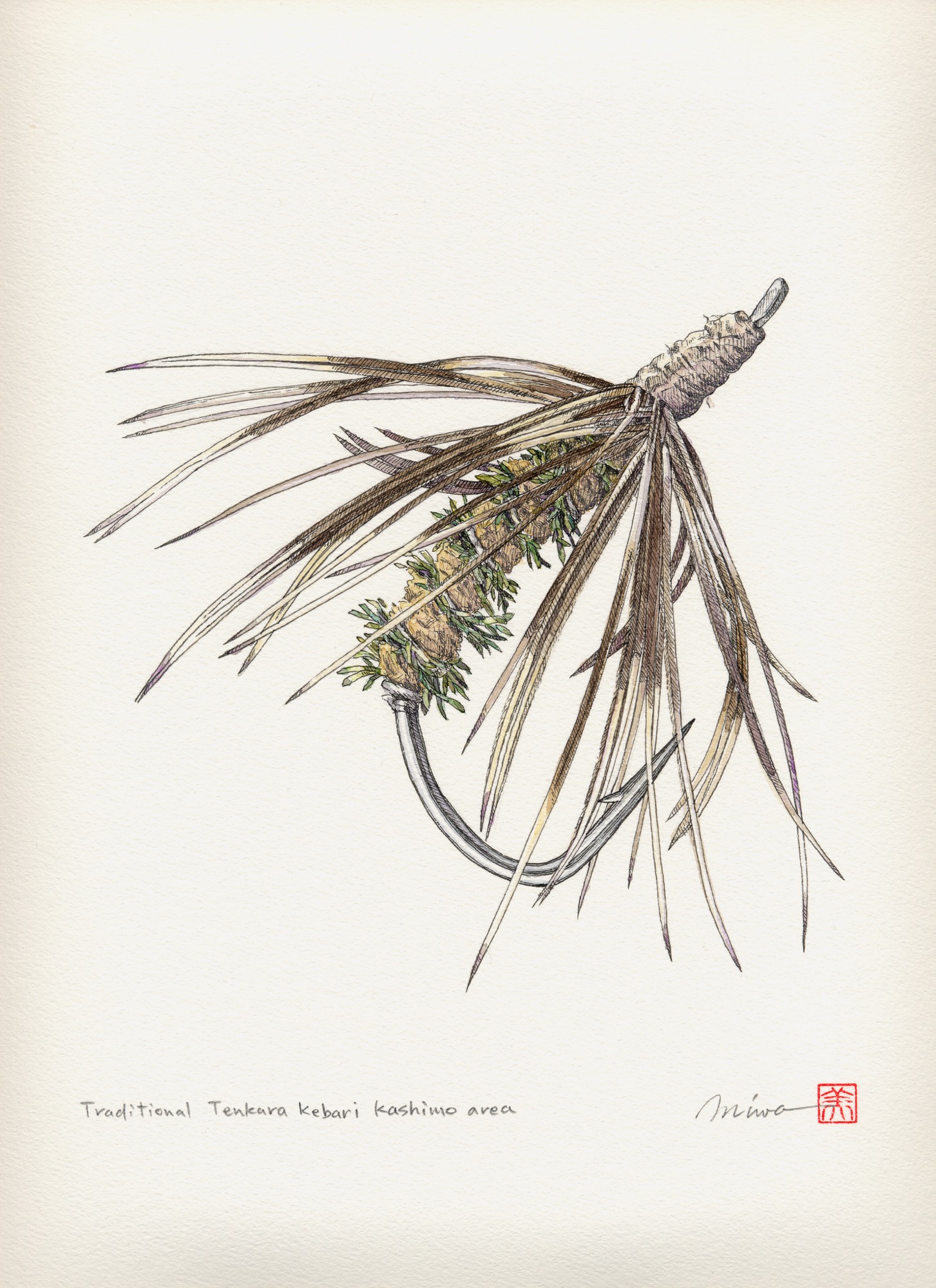

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel

Upon returning from Japan, my mind was filled with the mountain culture of tenkara, a traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. I had to share my discovery with the people at home. My next journey was founding Tenkara USA.

Clinging to mossy rock with half my body under a waterfall, I watched the torrent crash into a small basin fifty feet below, sending mist into the air and soaking my companions. Mr. Futamura observed apprehensively. Next to him, Mr. Kumazaki preferred to stare at the pool in front of him for any signs of iwana, the wild char found in the mountains of Japan. A fishing rod, small box of flies, and spools of line and tippet were stowed away in my backpack. No reel required.

As tends to happen with shing, we lost track of time somewhere along the way and now faced the crux of the trip. It was seven o’clock in the evening and would soon turn dark inside this lush forest. After a full day of rappelling, swimming through pools in impassable canyons, climbing rocks and waterfalls, and, of course, shing, we were all tired. The route ahead looked straightforward and within my comfort zone, the only caveat being a very wet climb.

My task was to climb to the top, set up an anchor, and belay my partners up. Twenty feet from the top, features on the rock face disappeared on the drier left side and forced me closer to the waterfall, where thick moss oozed like a wet sponge. I was long past the point of no return. I pushed past the fear and focused: hands and feet, hands and feet, hands and feet. The banter between Futamura and Kumazaki suddenly stopped. All sounds, including the roaring of the waterfall, seemed to vanish.

Getting there

My trip to Japan was a journey of discovery. For two months, I stayed in a small mountain village, learning everything I could about the one thing prompting my journey: tenkara.

In reality, I already knew a lot about tenkara. Three years earlier, on my first trip to Japan, I introduced myself to this traditional Japanese method of fly-fishing that uses only a long rod, line, and fly—no reel. After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love. I imagined how great it would be for backpacking and introducing people to fly- fishing in a simple, fun way. There were just so many possibilities.

"After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love."

With little information and no gear available stateside, I took on the task of introducing tenkara to the United States. Over several long months, I created Tenkara USA and since 2009 have been introducing tenkara to anglers outside of Japan. However, despite the knowledge I gained in the last three years, particularly under the tutelage of Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, Japan’s leading authority on tenkara, I knew there was much more. Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers.

"Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers."

History of tenkara

Just as the practice of metalworking appeared independently in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East and among the Incas in South America, evidence suggests that fly-fishing emerged in Europe and Japan independently of one another. Tenkara is similar to the original mechanics of fly-fishing practiced by the likes of Dame Juliana Berners and Charles Cotton, the best-known historical practitioners of fly-fishing in the West. Anglers have practiced similar fixed-line methods in many other parts of Europe, including Spain, France, Italy, and Poland. Yet, unlike the original Western fly-fishing methods, tenkara still lives in Japan.

One main distinction separating tenkara from Western fly-fishing is its origin—tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes. While the West went to work designing fly patterns, weights, strike indicators, and other gadgets to control the reach of a fly or make the activity “easier,” the typical tenkara fishermen of today adhere to the original practitioners’ thrift and reliance on skill. At the risk of seeming irrational to a Western fly angler, most tenkara anglers rely on only one fly pattern, no matter where they fish or what is hatching. As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice.

"Tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes."

"As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice."

Ancient and mysterious origins

Tenkara felt like my own personal Machu Picchu. Here was a rich but hidden mountain culture relatively unknown to the West, so unpublicized that the coastal Japanese themselves only became more aware of it in the second half of the twentieth century. Although researchers can find numerous Western fly-fishing references going back as far as AD 200 or beyond, in Japan, records of the sport only travel back a few generations before disappearing into the forest along with the original, albeit illiterate, practitioners of tenkara.

Even the origin of the name, tenkara, is unknown. The phonetic reading of ten kara could give it the meaning of “from heaven.” However, the name is written in katakana characters, a Japanese syllabary mostly used for words of foreign or unknown origin. This leaves few clues but opens several theories on the original meaning of the word. The most common stems from the way a fly lands from a fish’s perspective, as if it were coming “from heaven.”

Until recently, in most parts of Japan, the method was referred to as kebari tsuri. Kebari means “haired hook” (artificially), and tsuri means “fishing.” In the late 1970s, as the Japanese rediscovered traditions such as tenkara that had flirted with extinction during periods of dramatic economic dislocation, a handful of tenkara enthusiasts began using the term tenkara exclusively to clearly differentiate the practice from other types of fly-fishing. Nowadays, in the appropriate context, it’s used to describe fly-fishing sans reel.

The adventure

I wasted no time getting to the mountains of Gifu prefecture, the region of Japan where tenkara possibly originated. Two friends from Tokyo met me at the airport, we loaded into a rented Nissan and immediately headed for the mountains. The suburbs of Tokyo sprawled endlessly on both ends of the city, a sea of lights with tiny rice paddies in lieu of backyards. Mountains on the horizon appeared impenetrable, abruptly bordering the suburbs as though the country were too small for foothills.

The seven-hour drive southwest was a bridge between two worlds, betraying how a mountain culture could have remained unexplored within a country the size of California. Traveling at sixty miles per hour I imagined how, just a hundred years ago, it would take a full day to cover what I did in ten minutes. I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years.

"I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years."

We arrived in Maze, a small mountain village of approximately 1,400 souls in the prefecture of Gifu. Kazuhiro Osaki, who goes by the name Rocky, and his wife, Ikumi, would host me during my stay. For several years, Rocky and his wife have managed the Mazegawa Fishing Center, a tourist center established on the banks of the Maze River to promote angling tourism and other activities in the area. Their home was quaint, my lodging a traditional tatami room with its typical grassy fragrance. A seat at the kitchen table provided a clear view of the mountains to the south. Being the monsoon season, sparse clouds frequently enveloped the mountains. I couldn’t have asked for a more scenic location or for better hosts—it felt like a dream.

Most mornings evolved into a pleasant routine of writing and taking care of the business side of Tenkara USA while drinking a cup of coffee and enjoying the mountain views. In the afternoons I visited the fishing center and tried to uncover the different layers of tenkara through fascinating interviews and encounters with individuals who made (and continue to make) its history. In the evenings, I’d try to fish the yumazume, loosely translated as the “evening activity period,” until it got too dark to see.

A living tradition

Perhaps the mountain culture of tenkara has always been too rich to ever really be at risk of true extinction. Talking to some early Japanese explorers of the tradition, I wonder how close Japan came to losing tenkara.

Eighty-nine-year-old Mr. Ishimaru Shotaro heard about my curiosities through the region’s social network. He came to the fishing center to meet this gaijin (foreigner) who was so interested in his tenkara. He guessed it was 1934 when he began watching a tenkara angler near his hometown of Hagiwara. He explained that approaching a stranger to ask about his techniques simply wasn’t done at the time. Keeping a subtle distance, Shotaro-san followed the angler for an entire summer, periodically going off on his own to try out the techniques he observed. This is how he learned tenkara, then taught others in the area, and is now often referred to as a tenkara meiji, or “tenkara master.” Without any records to prove otherwise, Shotaro-san may have been the rst tenkara teacher in the country.

I asked him why today’s young people think that fishing is difficult—despite the availability of books, magazines, and videos—even though Shotaro-san taught himself the practice simply through observation. He responded simply, “There were a lot more fish back then.” Mr. Shotaro described how at that time, when the damming of the rivers that accompanied Japan’s industrialization was far from complete, he often caught 100 fish a day, with a personal record of 150, numbers common and somehow sustainable among the professional tenkara anglers of the time.

“There were a lot more fish back then.”

When I met him, Shotaro-san couldn’t trust his body the way he did a decade earlier. His legs started giving out three years ago, and since that time, he had not visited the water. Nonetheless, one hour of talking about tenkara was just too much for him to bear. As he had done a hundred times in our conversation, every time he remembered a story about fishing and his youth, he smiled. But this smile was different. I could tell he wanted to fish again. In a very soft voice he turned to his nearby student and said, “Tsuri o shimashoo!”—“Let’s go shing!”

After helping him put on waders, his student and I assisted Mr. Shotaro into the waters of the Maze River. Mr. Shotaro said he wanted to fish with me, since he didn’t know if he’d ever have another chance. With a new vigor, his casting was fluid and precise, the manipulation of the fly enticing. In a stretch of river that had yielded few fish in the two months I was there, Shotaro-san got a fish to rise on his third cast.

Stolen technique

In the early 1960s, the practice of tenkara was as mysterious as it had been in the prewar period. Katsutoshi Amano, a name known to all Japanese tenkara practitioners, had to learn the sport exactly the same way Shotaro-san did before him. As Amano-san said, “Asking a man about his technique just wasn’t done at the time; I had to ‘steal’ the technique from him.” Ironically, given their age difference and the fact that both are from Hagiwara, there is a good chance the man Amano-san followed and mimicked was Shotaro-san himself.

Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, my principal tenkara teacher, and Mr. Amano were instrumental in popularizing tenkara among the Japanese starting in the late 1970s when Japan, at the height of its economic boom, began to rediscover itself and its traditions. In 1985, Japan’s largest TV network produced a segment on the sport, giving people throughout Japan an idea of what tenkara was about. Nowadays, newcomers can look it up online, watch videos, and choose from a collection of books and magazines that offer lessons on knots, flies, and techniques. A once-secretive practice that provided employment to landless peasants is now a source of fascination to urbanized Japanese and a growing number of participants in the United States and other countries.

Tenkara with a twist

Two months went by faster than the glimpse of a rising trout. But I was happy I had found the time to fish a little on a daily basis. My worst fear was that I’d end the journey wasting a lot of time and not “finding tenkara.” I feared my relatively reclusive nature would send me deep into the mountain streams searching for the soul of tenkara anglers from centuries ago, rather than seeking people who are alive and carrying on the tradition.

My fear of wasting time didn’t come true. I enjoyed incredible encounters with old masters, meetings with craftsmen, a very enjoyable time with my hosts and their friends, and a lot of fishing, too. But I also craved adventure.

The same isolation early tenkara fisherman enjoyed was a little more difficult to achieve in modern Japan. So we took to the challenge with canyoneering shoes, neoprene wetsuits, ropes, and harnesses, and our tenkara kit, mixing fishing with what is known as “shower-climbing,” a mix of canyoneering with climbing waterfalls. It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. Our portable gear didn’t add weight to our packs, and the telescopic rods could quickly be stowed away as we prepared to climb a waterfall. By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there.

"It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. ... By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there."

We set off on an expedition that took us to rugged tenkara-perfect mountain streams, far from the masses that leave many streams ravaged and devoid of fish. Out here, I finally felt the spirit of tenkara fishermen from eras gone by: They disappeared into the forests for weeks at a time, camping and fishing the streams, drying caught fish, and finally, when the catch threatened to be too heavy to carry out, headed back to the village markets.

We planned to build a fire by the river, where we would cook a trout “shioyaki-style”—only sea salt coating the skin, a firm branch serving as a skewer. And we would drink kotsuzake, a drink that, as I have come to appreciate, is underpinned with ceremonial and philosophical significance—though one shouldn’t picture a neat Japanese tea ceremony.

Kotsuzake is primitive and raw. Preparing and drinking it is an act of homage to the principle of not wasting the resources nature provides. After separating the bones from the meat, we placed them over the coals of the re to lightly roast and bring out oils and flavor, then immersed them into the warm sake. The result is sake with subtle and tantalizing fish flavors—all part of the Japanese mountain culture, and now a personal practice if I must eat a trout that I catch.

The cliff-hanger

Back on the treacherous, wet rock face, a small overhanging cluster of bamboo far to the left started to seem more reasonable the longer I clung immobilized by the waterfall. I normally would never trust plants to hold my weight over a fall that could potentially kill me, but at this point, adrenaline dictated my actions. I grabbed a bamboo stalk and slowly shifted the weight off my feet. I placed my trust in a root system that was out of sight under a thin veneer of soil. Through the patch of bamboo and other vines, I finally topped the cliff, beaming in relief. Under heavy rain, I wrapped an anchor rope around an ancient tree lying across the stream. When Futamura-san reached the top, he looked down at the pool below with a nervous smile and said, “Good job; difficult climb.” △

The Figure Sculptor

Alpine Modern visits Swiss-born artist Roger Reutimann at his studio in Boulder

Inspired by the human form, Swiss-born artist Roger Reutimann found his way to sculpting for the rich and the royal via a classical music education, curating art fairs, and product design.

Roger Reutimann captures elegant sensuality in his sculptures of human figures. Born in a secluded village in Switzerland, the artist, a self-proclaimed Renaissance man, has devoted himself to pursuing and mastering many art forms. His evolution from classical pianist to figurative realism painter to internationally known sculptor has secured his place as one of America’s most sought-after contemporary artists.

Early Reutimann

As a young pianist, he found himself drawn to classical composers and music that stirred his soul. He studied at the Zurich Music Conservatory and was soon performing as a classical concert pianist throughout Europe and competing in international piano competitions. Traveling provided artistic influences at an early age as he experienced Europe’s rich cultural heritage.

His love of music flowed into a career as both a realist figurative painter and a co-owner in the Forum International Art Fairs in Zürich, Hamburg, and Düsseldorf. Galleries in Zürich, Milan, and London represented his paintings, and he received innumerable awards, honors, and recognitions. Relationships with gallery owners and collectors worldwide would follow him into his future calling as a sculptor and continue to advance his reputation as a world-class artist.

The Renaissance man emerged again as Reutimann turned his creativity to remodeling his first American home in Miami, Florida, with distinctive and extensive flourishes, from mosaic tiles to stained glass windows and Tudor-style ornamental plaster ceilings. The spectacular manor has been featured in architecture magazines and leased by production companies for films and commercials.

“In the midst of remodeling the house, one day I took a sculpture class to fill the time and loved it so much I gave up painting right then. To me, sculpting is like painting a thousand paintings. It has another dimension, and, therefore, it is so much more real than a two-dimensional image. A painting is only an image of life, but sculpture is life,” says Reutimann.

“To me, sculpting is like painting a thousand paintings... A painting is only an image of life, but sculpture is life.”

Coming to Colorado

Reutimann’s love of the mountains prompted a move to Boulder, Colorado, because of its similarity to Switzerland and the expansive open spaces. “I would rather sit on my back porch watching the sun set over the Rocky Mountains than in a high-rise flat in New York City,” shares Reutimann, for whom Colorado evokes memories of his native country.