Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Alps // 40

An unfiltered, low-speed journey across Swiss peaks in words and images by Boulder photographer Jamie Kripke

Slowing down gives us more time to look. Having more time to look changes how we see. I wanted to slow down.

Using alpine touring skis, a small backpack, a folding medium-format camera, and twelve rolls of black-and-white film with ten exposures per roll, I set out to traverse and photograph a high route across the Alps. Each piece of equipment for this trip was chosen for its simplicity as well as its limitations—and for the extra time, attention, and patience it requires.

Traveling up and over mountains by skis has a way of shifting time away from something that is measured in minutes, hours, and days. Ascending one step at a time through untracked snow, the units become ski lengths, pole plants, breaths, sips of water, bites of food, daydreams, changes in weather or light.

The physical limitations of low-speed film in a mechanical camera call for a heightened attention to composition, exposure, and technique. Every frame becomes its own unique experience—one that builds gradually with each precise movement of the camera, each small adjustment for focus, aperture, or shutter speed.

"Every frame becomes its own unique experience."

Once I’ve settled on an image, I take a deep breath and try to be as still as possible. High in the Swiss Alps, in the space between the breath and the click of the shutter, time slows to a stop.

"High in the Swiss Alps, in the space between the breath and the click of the shutter, time slows to a stop."

These images were made over the course of eight days, and selected from a total of 120 images, where just one exposure was allowed for each image. They have been minimally altered from their original form in order to stay true to the tonality of the film, and are the pure, unfiltered, timeless compositions that I’d been looking for. △

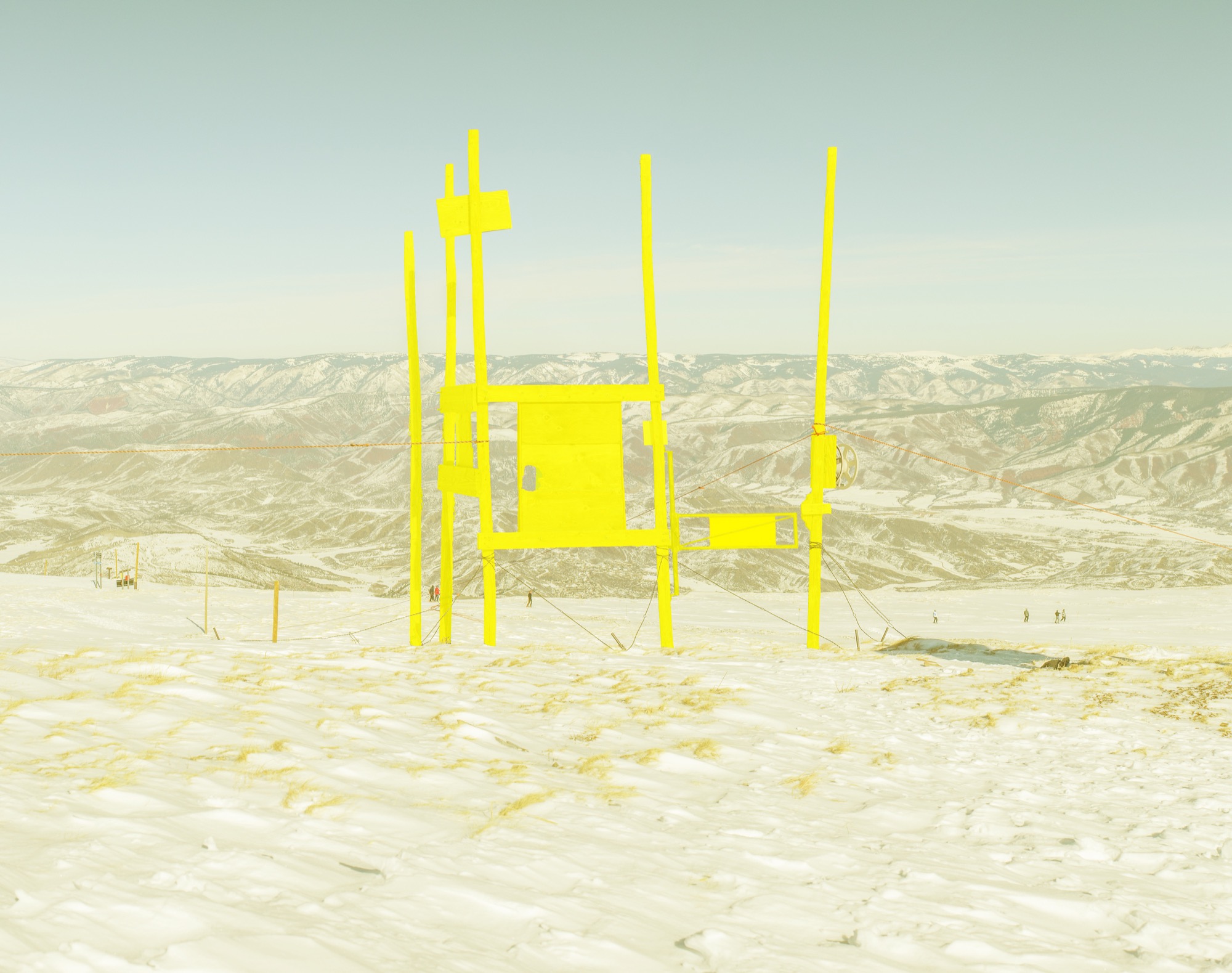

Alpine Modern + JK Editions: Fall

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints by Boulder photographer Jamie Kripke exclusive for Alpine Modern

Art Photography by Jamie Kripke A portfolio of images by Boulder, Colorado-based photographer Jamie Kripke, created exclusively for Alpine Modern. An ongoing project that studies our connection to the alpine landscape.

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints of these images are available to purchase through Alpine Modern.

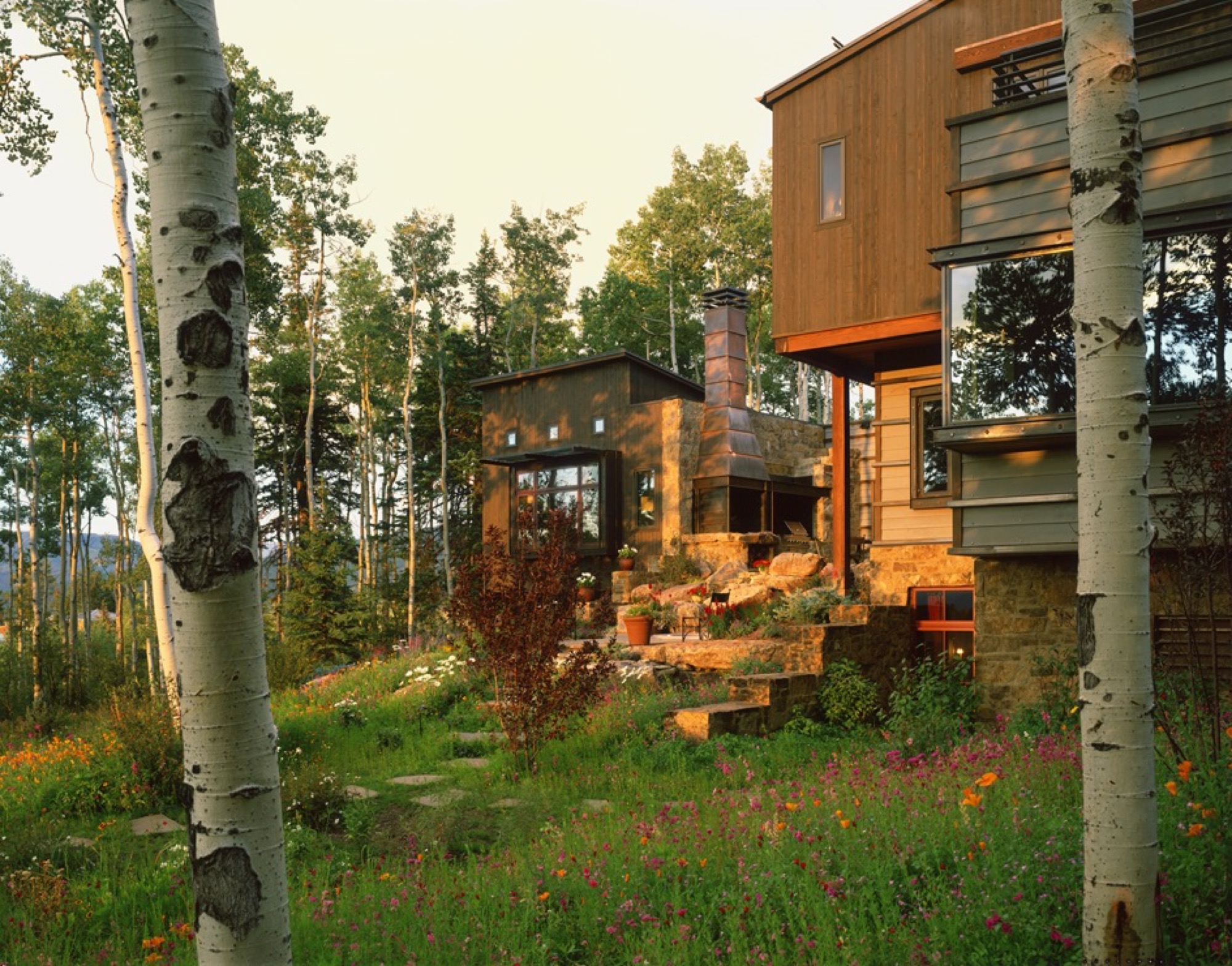

The Architect Explorer

Colorado architect Larry Yaw interviewed by his journalist daughter

Colorado architect Larry Yaw, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, has nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond. An intimate conversation with his journalist daughter...

Sitting on a mossy rock in a tall stand of aspens next to my dad, a couple of hours into trying to find our way from Willow Lake back to the Maroon Bells parking lot, I started gnawing on my mom’s teriyaki beef jerky from my backpack. We had left the trail long ago, and I was convinced we were lost. I must have been about eight years old at the time.

“We’re not lost, we’re exploring,” is probably how my dad, architect Larry Yaw, responded—a claim that would echo through my young years as I followed him through the backcountry of the Elk Mountains in Colorado, across Kashmir in India, and through The Wind Rivers, The French Alps, New Zealand, and beyond, along with my mom and three siblings.

We got lost a lot, sort of on purpose, in the mountains. Yet never once did I see my dad flinch in these moments. Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul. I’d watch as he’d get this shrewd sparkle of excitement in his voice as he strategized on which ridge to follow, or which drainage would lead us back to the tent, all the while managing his family on the verge of the fearful discovery that our dad, really, had no idea where we were. Yet, now, as I bring my own young family into the woods to play and discover, I realize that my dad’s resourceful and poetic confidence that has intrigued me over the years has penetrated my own psyche deeply, and I strive to encourage that sensibility to seep into my kids’ sense of adventure. And, just as he did for our family, my dad has left an indelible impression on the contemporary design ethos of the Roaring Fork Valley, as well as countless alpine communities across the Mountain West.

“Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul.”

Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond, with an exceptional roster of clients and creative business partners as his co-conspirators; and he propelled them towards the outer edges of what’s possible. If I were to guess, his clients might sum up his character with a story similar to mine, yet the chapel would be his drafting table, and the map would be the radical ideas he has hand-sketched on camel-colored paper for the artfully crafted architecture he has envisioned. Sure, during his forty-six years creating innovative designs in the mountains, his aesthetic has shifted and grown, but his passion for the rawness of the backcountry, and for the purity of connecting people to place and to nature has remained firmly in tact.

“Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond.”

As his youngest daughter, I knew all of this, sort of, but it wasn’t until we had this conversation that I truly understood the gravity of how particular vignettes throughout his life have justified, and even come to imprint themselves, on his design, his spirituality, and his personal approach of getting lost—before finding a path.

Herein lies our recent sit-down at the kitchen table, an intimate chat between an architect and his daughter:

LYR How has living in the mountains influenced your design?

LY I’m the guy who can’t stop myself from climbing up and looking to see what’s on the other side of the ridge, or from going up to the end of a valley to see what’s there. If there’s some association with exploring, and innovating beyond the expected, I’m in. Therefore, my lifestyle has been defined by, and inspired by, active outdoor living, and attached to that is the adventure of it. Adventure is a part of everything I love to do—physical, intellectual, and spiritual adventure. And, therefore, I’ve begun to regard the artform of architecture as a basecamp for this; a basecamp that is sustainable, economic in scale, but very much connected to nature as that is so much a part of the adventure of being alive and in the now, wherever here is.

“Adventure is a part of everything I love to do ... I’ve begun to regard architecture, or habitation anyway, as a basecamp for this.”

LYR Who influenced you as an architect?

LY First, the biggest influencers have been great clients of a contemporary persuasion, who relish the process of exploration and testing. There are other architects also, such as Romaldo Giurgola (“Aldo”), The Dean of Columbia School of Architecture, where I completed my Master’s studies. He would sit down and talk in these simplistic terms about the choreography that you create architecture through; the path you take and how that enriches you, and enriches the purposes of design. Louis Kahn—his work and writings inspired me.

And, the firm Morphosis Architects creates fabulous, courageous, contemporary, sculptural, and adventuresome architecture. As you traverse their spaces, you’re taken through them with this marvelous, layered, spatial experience that therefore inspires the choreography of getting from here to there.

LYR What’s your experience of being a modern architect in the Roaring Fork Valley, where opulent traditional mountain architecture is so dominant?

LY There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things. Even though I’ve been involved with opulence, I design around the expectation that you don’t let the house own you. And, now, there is a cultural shift toward an awareness that we have to be stewards of the land, and be mindful of not writing out a big order for the resources. That shift has brought clients who want thoughtfully crafted, understated, simple in form, and more directly responsive design.

"There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things."

Also, a townscape is really a library of cultural expressions over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time. Hopefully, what I do is an expression of my times and this culture, and doesn’t grab a crutch out of architecture’s past. Because the work of my firm significantly influenced the evolving character of architecture in the New West, I was elevated to the prestigious College of Fellows (FAIA) by the American Institute of Architecture. Our working mantra of design is that of “place-making” where architecture and nature are seamlessly integrated to the betterment of both.

“A townscape is really a library of culture preferences over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time.”

LYR You were raised in rural Montana. What did that upbringing impart to you?

LY Growing up in Montana, I really experienced these rural ranch and farm compounds that were formed over generations. They were always designed by the simplest means, in simple forms, and they seemed to sit respectfully on the earth. When I started studying these things, I discovered that they were really forms that described contemporary architecture in their simplicity. They were formed in protective surrounds, and were organized around working proximities, yet there was always a place for enrichment, like a little garden near the front porch. Then, these compounds grew organically—out of inelegant purpose, and rural rationality. I didn’t appreciate it then, but as I studied architecture, I started pulling out of my experiential self, and those things all matched up—that is contemporary architecture. It did not tread heavily on the land; it embodied economy of means; it had simple forms and echoed its context—all things that are generationally taught or experientially taught. They solved problems there, out of their own devices and their own means.

LYR How has design carried into, and impacted, other areas of your life?

LY It has opened my eyes. When I travel, I see different things; I wonder about them; I take them in. And, what I’ve learned is that I like evocative things. Evocative means you hate it or you love it but it nevertheless stirs emotion in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind. And, that’s true in architecture. The creative process and everything associated with it; the people you work with and the collaborations—they fuel my worthwhileness and my sense of adventure.

“I like evocative things…. You hate it or you love it but it stirs something in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind.”

LYR Tell me about the Blackfeet Indians, a tribe you became close to when you were young, and their impact on you, your design, and your art.

LY When I was twelve years old, I went to Browning, Montana, in the middle of the Blackfeet reservation, and there sat this gorgeous little Indian girl. She was about my age, dressed in a traditional beaded, white doeskin dress, and I was enchanted. Her name was Virginia Home Gun. That enchantment turned into a friendship with her. It turns out that her father was the chief of the Blackfeet Tribal Council. Over time, through traditional ancient ceremony, they made me an honorary member. That really stirred me. It continued beyond that, and I started reading and studying about the rituals and legends that were the spiritual glue of their life. The Blackfeet regarded themselves as a creature of the earth, and they understood the balance of their needs with earth phenomena. They would give thanks to the buffalo, and honor a slain enemy for valor. For me, it went from the idealistic warrior image when I was young, to understanding their spiritual nourishment that kept them who they are. That translated to me later on into a series of paintings that I call “Once Proud.” That’s my way at this point in life of telling the story of westward movement and how it maimed the spirit and freedoms of our native inhabitants of this place. This made us feel sort of culturally guilty and I was inspired to tell that story.

LYR What is the status of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley, and what role did you play in getting modern design where it is today?

LY Aspen has always been a place that embraced aesthetic adventurism, or tolerated it anyway, and has always fostered intellectual and artistic courage. My firm, my partners, a highly talented thirty-some staff, and our clients have allowed us to be one of the forerunners of the movement here. Personally, I haven’t pushed modernism [in the valley] for recognition; we have had clients and circumstances that permitted that kind of solution and character. But within my firm, I’m known for pushing beyond the expected, and going to a higher level of art form and different level of expression; questioning, pushing, improvising, and going beyond even what clients want. Straight competency in architecture is a mid-level solution—I advocate for artfully courageous and innovative solutions that are bigger than the problem.

LYR Who are the people who want modern architecture in the mountains? What makes them different from the “typical” client who wants that enormous heavy log mansion that says, “I have a lot of money, and I live in Aspen?”

LY Some people are here because it is a new bar on their reputation epaulette. The people who I gravitate towards, or who gravitate towards our firm, are here for reasons I’ve sorted out—for the adventure, the backcountry, and things that support our minds, bodies, and spirits. These are all truly good characterizations of our lives, and our personal culture. To put it into context, I’m not going to design three little sitting areas around the master bedroom so you can sit inside all day. You get out of bed, you have breakfast, and you go ski; you get out there.

In that, a question I always ask is: Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context? The answer is both depending on where you are, but it's a question I ask of it because its one of the beginning points that I use to align my sensibilities with those of a client or a place.

“Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context?”

LYR You get lost on purpose, in a way, right? How has this personal quality informed your design sensibility?

LY Freud said that problems couldn’t be solved by a consciousness that created them. In other words, you cannot solve problems where there are too many givens; otherwise you just spin inside the givens. Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost, I just feel like I entered another chapel as it engages another form of creativity, curiosity, and adventure in me. Being lost is inspiring too—when I was really young, out hiking and going to crazy places I’d never been, I marveled at earth forms, the magic to them, what got them there. As I went on, I studied geomorphology, and it all boiled down to tectonics of eruption, erosion, accumulation, weather, and all of nature’s will upon those things. It’s really compelling, and asks compelling questions, and I found some answers that I’ve portrayed in my painting.

“Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost.”

Nature can also help you appreciate your existence, be a stimulus for enlightenment, and fuel lifelong curiosities. As architects, we must embrace that kind of creativity and spirituality, the kind that enhances who we are, so as to create well being.

And, Lindsay, I can find my way back from anywhere.

A founding partner of Cottle Carr Yaw Architects, Larry Yaw has designed many of the firm’s award-winning projects—from resort and community design to corporate buildings and private mountain homes. In 1993, Yaw was named to the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows, the highest award given to the profession’s most respected architects. His projects are regularly published in architectural books and national design magazines.

Yaw received his Master’s Degrees in both Architecture and Urban Design from Columbia University and has since been a lecturer and design critic at several western universities. Believing in the importance of civic involvement, Yaw is also a founding board member of the Aspen Art Museum.

Becoming JK

Meet the immensely talented photographer and artist behind our JK Editions

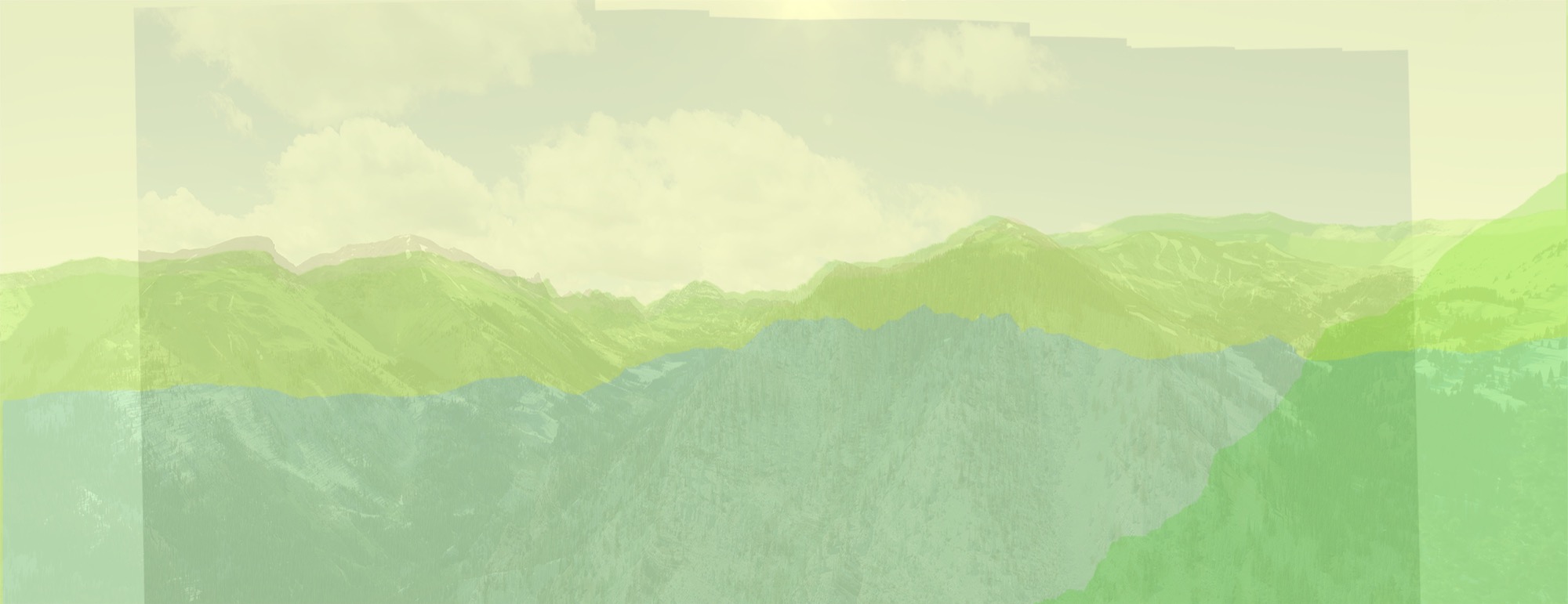

A studio visit with Colorado photographer and artist Jamie Kripke, who experiments with layers of images and color to create JK Editions.

Growing up in northwest Ohio, Jamie Kripke received mixed messages about making a career out of his love for photography. His mother, herself an artist, passed down her old Minolta camera to her son when he was fifteen. His father’s decision to buy a condo in Snowmass, Colorado, when Kripke was three jump-started a lifelong love affair with the mountains at a young age.

Kripke started snapping photos for the school newspaper at his Toledo high school. At the time, his mother’s 1973 Minolta XG-M with the macramé strap was “a gnarly camera to have for a kid,” he tells me. While his peers were playing with point-and-shoots with flashcubes or Kodak Instamatics, Kripke was teaching himself how to vary aperture and shutter speed for the perfect shot. He developed his own film and made prints in the school’s darkroom. His first published photo is a slim black-and-white of the high school football coach jogging toward the lens. And yet, Kripke put thoughts of pursuing a photography career out of his mind because “when you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

“When you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

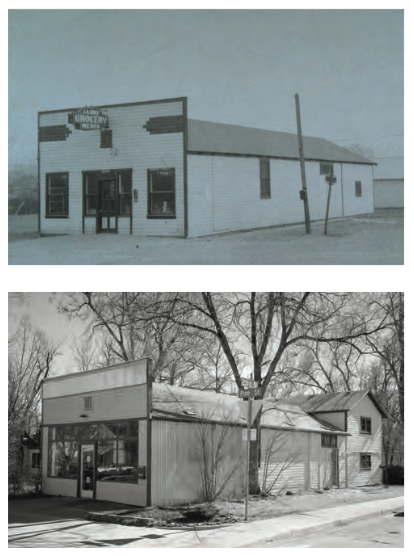

Today, Kripke is a professional photographer whose clients include Hewlett-Packard, Sony, Mini Cooper, and Visa. His editorial work has appeared in Dwell, Esquire, Outside, The New Yorker, Wired, and other publications. I join him at his Boulder, Colorado, studio on an unseasonably warm January day to learn more about his journey from high school newspaper photographer to successful independent artist. His corner studio has a deep history in the community, formerly operating as the local grocery, and before that, a horse stable. He’s been told that ghosts linger in the space. The white-walled studio is open and bright. We sit across from each other on facing vintage couches: mine a stormy gray with a mustard-yellow throw pillow, his a popping pink with a jade accent.

A simple white coffee table sits between us on a colorful striped rug. My eyes are drawn to a round clock hanging on the wall to my left; in place of numerals are songbirds—curiously, my own grandmother, mother, and aunts in Ohio all own one of these very clocks (my interviewee and I share the same home state). When I ask Kripke about the peculiar timepiece, he tells me that his father’s company in Toledo developed the original bird clock. “It has always been on the wall wherever I work as a reminder of my dad, his work ethic, and his business savvy,” he shares. Four mismatched desks of varying heights line the wall under the clock; there are no typical office chairs, but one desk has a short neon-orange children’s stool pulled up to it. The opposite wall is covered in framed black-and-white landscapes.

Kripke is a calm man; he sits cross-legged in jeans and a plaid shirt, answering my questions in a slow and intentional cadence. He explains that adventuring in the mountains of Colorado from a young age led him to the natural choice of moving to Boulder for college, where he dabbled in majors including pre-med and business before settling on philosophy. All those years, he was shooting photos with his old Minolta. In his bedroom back in Ohio, he had a poster of Bill Johnson, the downhill skier. He describes the image as a razor-sharp shot of the skier, airborne in a tuck and looking right into your eyes. As a kid, he’d often stare at the poster, wondering how on earth someone got that shot. On weekend ski trips to the mountains during college, he’d play around with photographing his friends:

“I was burning tons and tons of film to get one picture that didn’t suck.”

Kripke’s first breakthrough came a year or two after graduation, when Powder Magazine offered him seventy-five dollars for one of his images. This was a landmark moment in his photography journey; he recalls thinking, “Whoa, you can shoot pictures and get paid? That’s awesome.” The check and the letter from the magazine editor confirmed his deep longing to capture the world around him with his lens. He followed his curiosity to San Francisco, where he began assisting established studio photographers, a learning experience he likens to his graduate school. Spending much of his free time at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he began diving into the world of fine art.

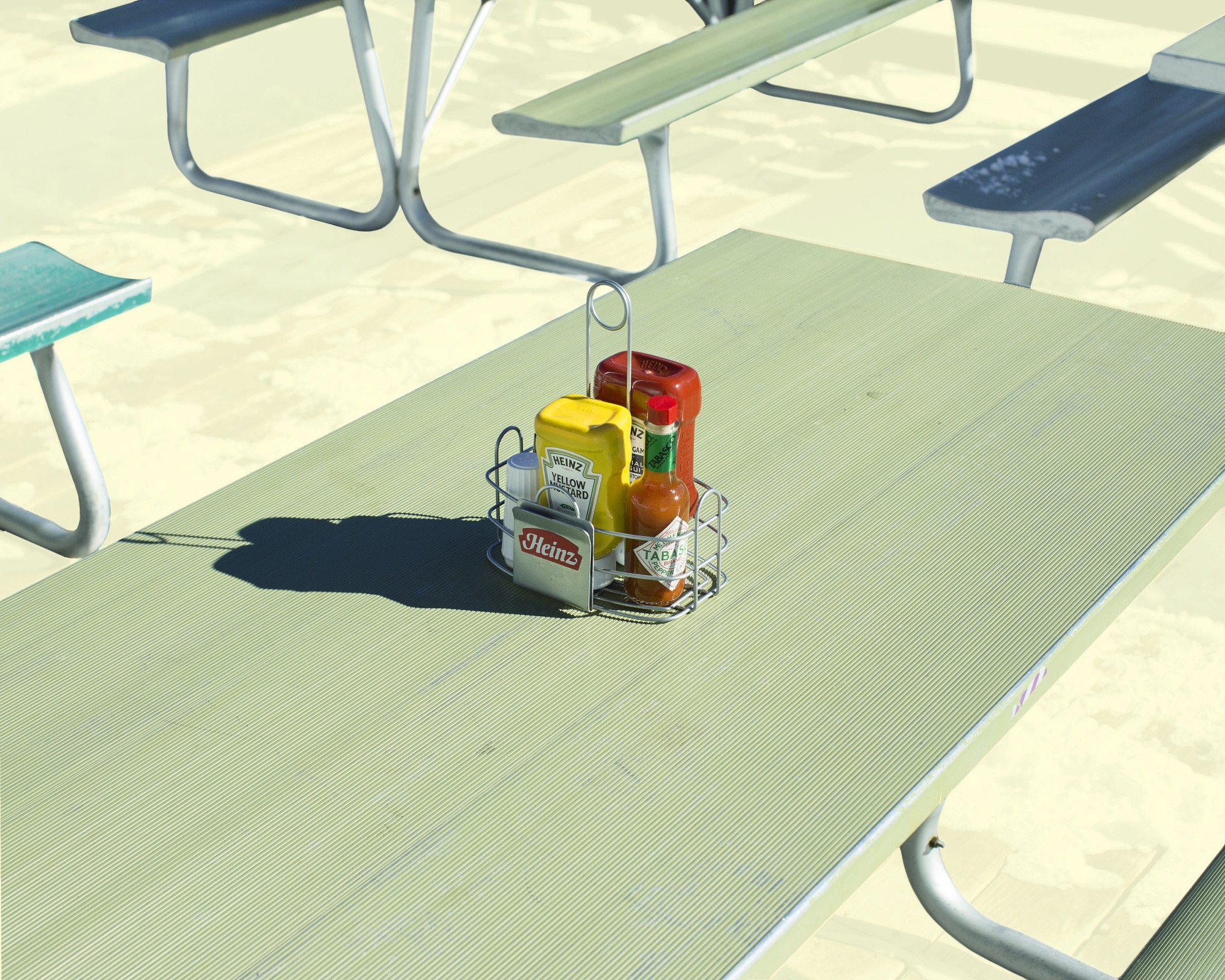

Observing other photographers and artists led to a natural curiosity about their techniques and guided him in finding his own approach. “[Photographer William] Eggleston was one of the first guys to pay attention to everyday stuff and to the ugly stuff. All of a sudden, I fully grasped this idea that photos are everywhere around us all the time, and it’s a little overwhelming.” Kripke’s interest in composition was sparked by Stephen Shore, who had a “gift for finding these compositions where your eye follows the path through the image. For me it’s like a seven-course meal.” And Jeff Wall, a Vancouver-based photographer who spent an entire year constructing one photograph, inspired Kripke to make the move from “something you find that already exists to something that you create from scratch yourself—taking versus making.” If he wanted to get serious about photography, he knew he needed to be able to make.

One day, while living in California, Kripke saw an old car with a mattress tied onto the hood driving on the highway. He laughed out loud at the curious sight and instantly knew he wanted to re-create that scene in a photograph. He left a note on his neighbor’s station wagon, got an old mattress from a homeless shelter, and researched how to light a moving vehicle. “It was the first picture I really feel like I made, that I fully put all the pieces together.” He still keeps that photo in his portfolio, even though it is ten years old. He reflects on the elements he pulled together from his role models: Gregory Crewdson’s moody lighting, Robert Bechtle’s nostalgic subject matter, Stephen Shore’s composition. “In some ways this picture encapsulated all this stuff that I had been paying attention to up until that moment, and I was lucky to be able to turn it into a single image.”

The plunge

All the while, Kripke still had one foot in and one foot out of photography as a profession. “There are different stages of commitment. There’s the first stage where you think, ‘Hey, maybe I should try this.’ But there’s another stage, much farther down the road, when you have to be really serious and make a real commitment to not turn back.” While working as an assistant to other photographers in his twenties, Kripke had a paycheck to count on. But could he build a viable career on his own? Unsure, he met with a career counselor when he was around the age of thirty. “I was at a point where it was time to decide,” he remembers. That’s when he got the push he needed: “The career counselor asked me what’s been the longest relationship I’ve ever been in, and I said, ‘About a year.’ Then she asked me how long I had been taking pictures, and I said, ‘Since I was fifteen, so fifteen years.’ And she looked at me and said, ‘It’s time to get married, Jamie—to photography.’ That was the moment I knew it was time to go all in—not look back.”

Kripke decided to make the leap and commit to supporting himself with his craft, so he continued to self-educate by following his curiosity and seeking out teachers. He took photography trips. He drove a VW Bus around Europe in 2004, chasing inspiration until the van broke down, stranding him in the “Des Moines of Spain,” which provided new photography challenges for a long three weeks. Back in the States, he traveled to Santa Fe to study with Dan Winters, a portrait photographer whose work Kripke first saw in The New York Times Magazine. Finding an agent in San Francisco allowed him the flexibility to move back to Boulder. He now lives a block away from his studio with his wife, Kate, a psychotherapist, and his two daughters: nine-year-old Kinley (nicknamed “Nugget”) and six-year-old Bridger (aka “Hot Sauce”).

When I ask Kripke about his favorite creative project, he laughs: “Am I allowed to say Alpine Modern?” In addition to cover art and a black-and-white photo essay—“Alps // 40”— Kripke’s fine art photography series “JK Editions” has been featured in our printed magazine, issues 03 through 06. “I’ve really loved creating these landscapes for Alpine Modern because it brings together so many things that I enjoy—skiing, photography, art, being outside, exploring, creativity.” Kripke has come to the Rocky Mountains since he was three, and now as a Colorado resident, the alpine landscape continues to inspire his art: “The mountains are like my sanctuary. The mountains are where I go to recharge and be inspired and to exercise and to push myself and to build friendships and to scare myself. They offer so many ways to make us better people—or make me a better person.”

Color connections

The JK Editions use layers of photography, art-driven references, and color. Kripke begins each project by photographing architecture or landscapes. Back at the studio, he zeros in on what captured his attention in the first place and layers these elements with color: “We have emotional connections to certain colors, so the color is about trying to create that connection.” We walk over to the desk, where Kripke shows me his recent work for Alpine Modern: He layered six or seven photos of the same landscape in different seasons one on top of the other to create one complex image. The winter and summer scenes are stitched together, artistically suggesting spring.

He describes the experience of displaying his work: “When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Some of the best advice Kripke has received as an artist is to “change up your inputs.” He continues to look beyond photography for inspiration, seeking out painting, sculpture, music, books, and podcasts to avoid stagnating in one medium. His work is a reflection of this: “I think inspiration comes from unlikely places or maybe the combination of two things that you didn’t expect to see together.” He seeks to make something new by combining photos and mediums to progress a project “somewhere it hadn’t been before.”

“When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Kripke’s philosophy on life? “Just be honest with yourself, and be honest about what makes you happy.” When I ask him if there is anything else he would like to share, he laughs: “Everything’s for sale.” △

Alpine Modern + JK Editions: Winter

Limited edition fine art prints by Jamie Kripke

Photos and Art by Jamie Kripke A portfolio of images by Boulder, Colorado-based photographer Jamie Kripke, created exclusively for Alpine Modern. An ongoing project that studies our connection to the alpine landscape.

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints of these images are available to purchase at the Alpine Modern online shop.