Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Utahan Utopia

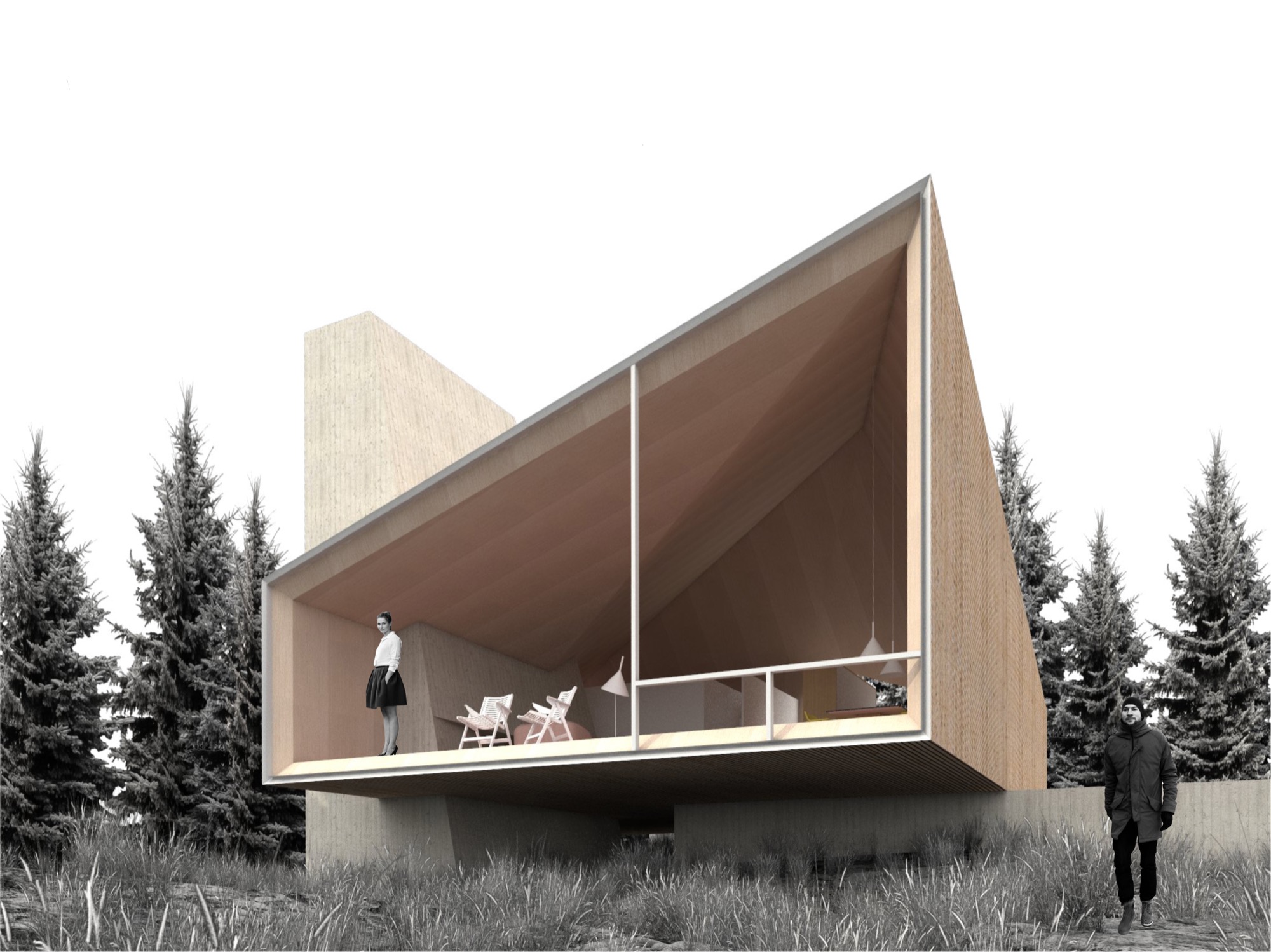

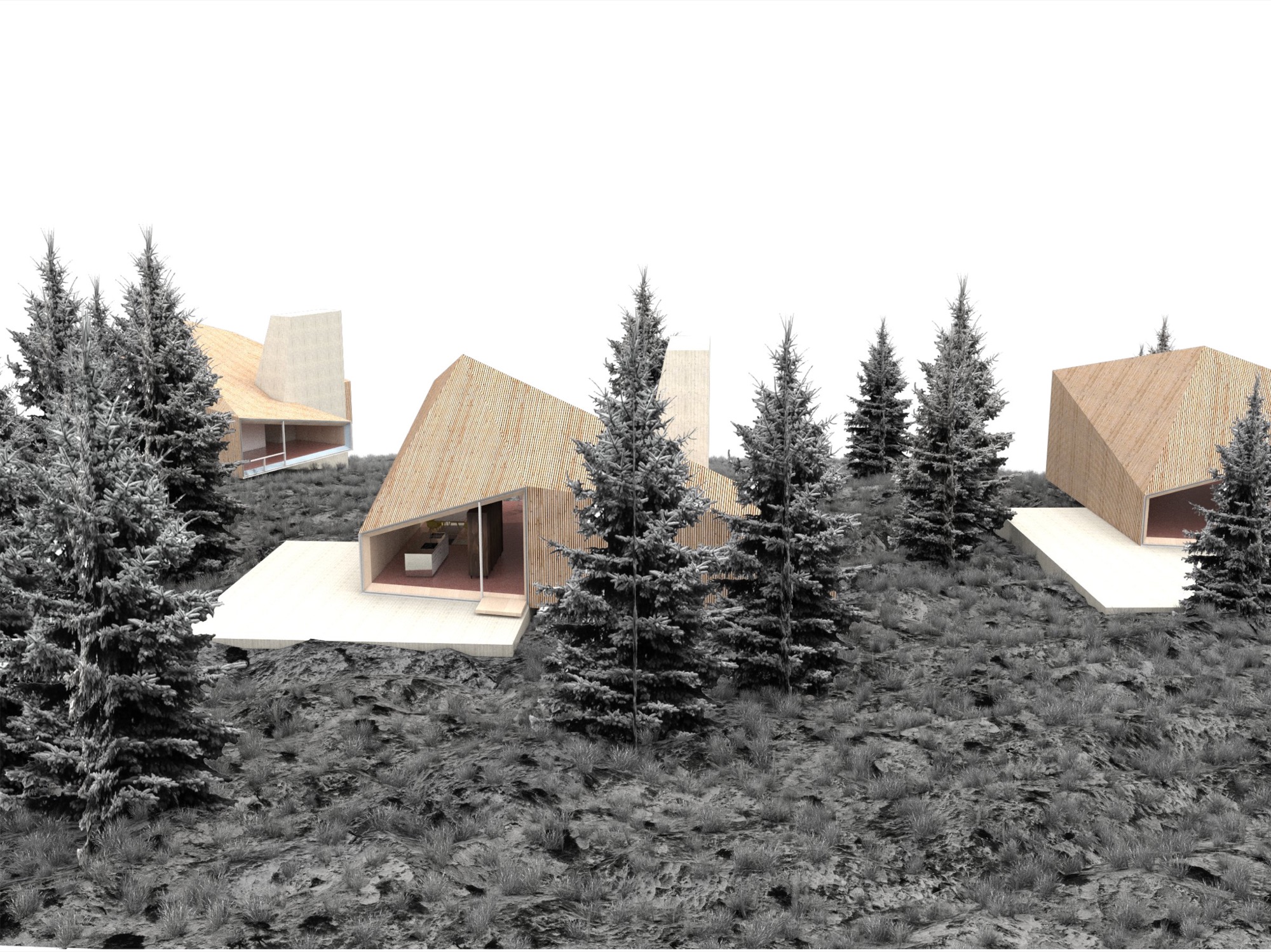

Summit Powder Mountain in Utah is a visionary colony of cabins designed by emerging Slovenian architect Srđan Nađ

A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the conversation on nature-respecting modern mountain architecture and communal living on Powder Mountain, where an enigmatic group of entrepreneurs, creatives, and altruists is building a pioneering alpine village. “We bought a mountain.”

So begins the backstory of Summit Powder Mountain, a visionary colony of cabins and an alpine village being dreamed up in Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

Elliott Bisnow and the Summit Series

Behind the idea is Summit, an event business started by Elliott Bisnow, a founding board member of the United Nations Foundation’s Global Entrepreneurs Council. What began as a small gathering of a few dozen investors, business whiz kids, and creatives over a short few years grew into the Summit Series: traveling invitational events that summon hundreds of thought leaders and different-thinkers from around the world. "What would it look like if Davos and Burning Man had a baby?" The Guardian rhetorically wondered in a recent article about the Summit Series. For its latest flagship event, Summit at Sea, 2,500 chosen attendees boarded a cruise ship in Miami for a four-day conference in international waters.

Rooting down in Utah

Now Summit is building a permanent base camp for its forums—a high-alpine town for its growing tribe to come home to. Summit purchased Powder Mountain, including the ski resort that has been operating there since the 1970s, with the vision to fundamentally reimagine and experiment with how people live together, shelter themselves, and converge for the greater good. “I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world,” says Summit design director Sam Arthur, who moved to Utah to see the project through. Since buying the mountain in 2013, Summit has called on sundry architecture and design gurus, even sacred geometry to conceive this test bed for communal living. But the group still needed a cohesive cabin concept, a trademark design that considers the demands of living at 8,400 feet (2,560 meters) altitude, of building sensibly on historically mostly undeveloped, pristine mountain land that includes an elk reserve, natural waterways, and thriving wildlife. A sheep ranch was the only settlement on the mountain for the longest time.

“I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world.”

Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition

Thus, Summit’s Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition challenged the global guild of architects, engineers, artists—masters and students alike—to design sustainable cabins that embody the leadership’s ideals of sustainability, use of natural materials, and humble expression. The winning concept would guide the architectural ethos for more than 500 single-family homes, limited to 2,500 square feet (232 square meters) on half- to two-acre lots. Arthur says they capped the size of the homes so Summit Powder Mountain could become a democratized, harmonious environment for the community at large rather than “this über-wealthy place that is about showing off how big and bad you are.” Larger lots of up to thirty acres, however, could potentially accommodate a compound design.

Choosing a winner

The winner: Srđan Nađ, a young architect from Slovenia. His prized design was inspired by a Summit event photo he had seen—a green meadow dotted with simple white tents, pure architecture integrated within thin cloth, pitched to create shelter from weather and wilderness. His other muse was the frontier cabin of America’s past, a simple wooden structure with a great stone chimney on the outside. “Combining both was my design concept for Summit Powder Mountain—a true connection with nature,” says Nađ, who believes “95 percent luck” won him the competition. More likely, though, he convinced the international jury panel, led by Todd Saunders of Saunders Architecture (Norway) and Jenny Wu from the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles, California), with his design’s adaptability and transformational potential. Arthur says, “Srđan did a beautiful job of meeting the criteria and applying a certain amount of aesthetic to it that really eloquently resolved that future/nostalgia-heritage/modern friction, which is at the core of what people respond to here, how they want to live in the modern age.” With its indoor/outdoor quality and what Arthur describes as “an obsession with light and views,” Nađ’s design captures the raison d’être for living on a mountain. “It’s a place to find refuge, to be inspired, to take in the natural primary source of beauty, and recreate with friends. It’s often very difficult to turn that into architecture, but Srđan took that and wrapped a building around it.”

Who is Srđan Nađ

Born to two architects in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1983, Nađ’s career choice was perhaps destined by birth. He attended a special building and engineering high school and spent his senior year abroad in upstate New York. He returned to Europe to study architecture at the University of Ljubljana, which he describes as a “boutique school” in the center of the city. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of architectural competitions and really test my ideas—and, of course, learn from my mistakes.” After practicing the craft with other studios for several years, Nađ founded Grupo H with his wife, a landscape architect. Based in Slovenia and surrounded by mountains and the outdoors, the company is dedicated equally to architecture and interdisciplinary aspects of planning and building.

“I grew up in Dubrovnik, Croatia, a great historic town by the Adriatic Sea, so I didn't have any understanding of the alpine world until my fantastic wife, a local Slovenian girl, introduced me to the alpine world of Slovenia and its natural environment,” Nađ says. “What’s special about Slovenia is that the mountains here are relatively inaccessible, and to get to know them, you need to hike a lot. Hiking is a local obsession here.”

Living in the small European country known for its mountains, outdoor recreation, and ski resorts—much like Utah—has transformed the man from the seaside. “When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective,” says Nađ. “It teaches you to admire and respect the wild nature of the alpine world. In the end, when you are put into the position to design a building for such a surrounding, all your knowledge and memories come together to create this unique combination of simplicity and elegance that a building high in the mountains demands.“

“When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective.”

Nađ's "Wooden Tents"

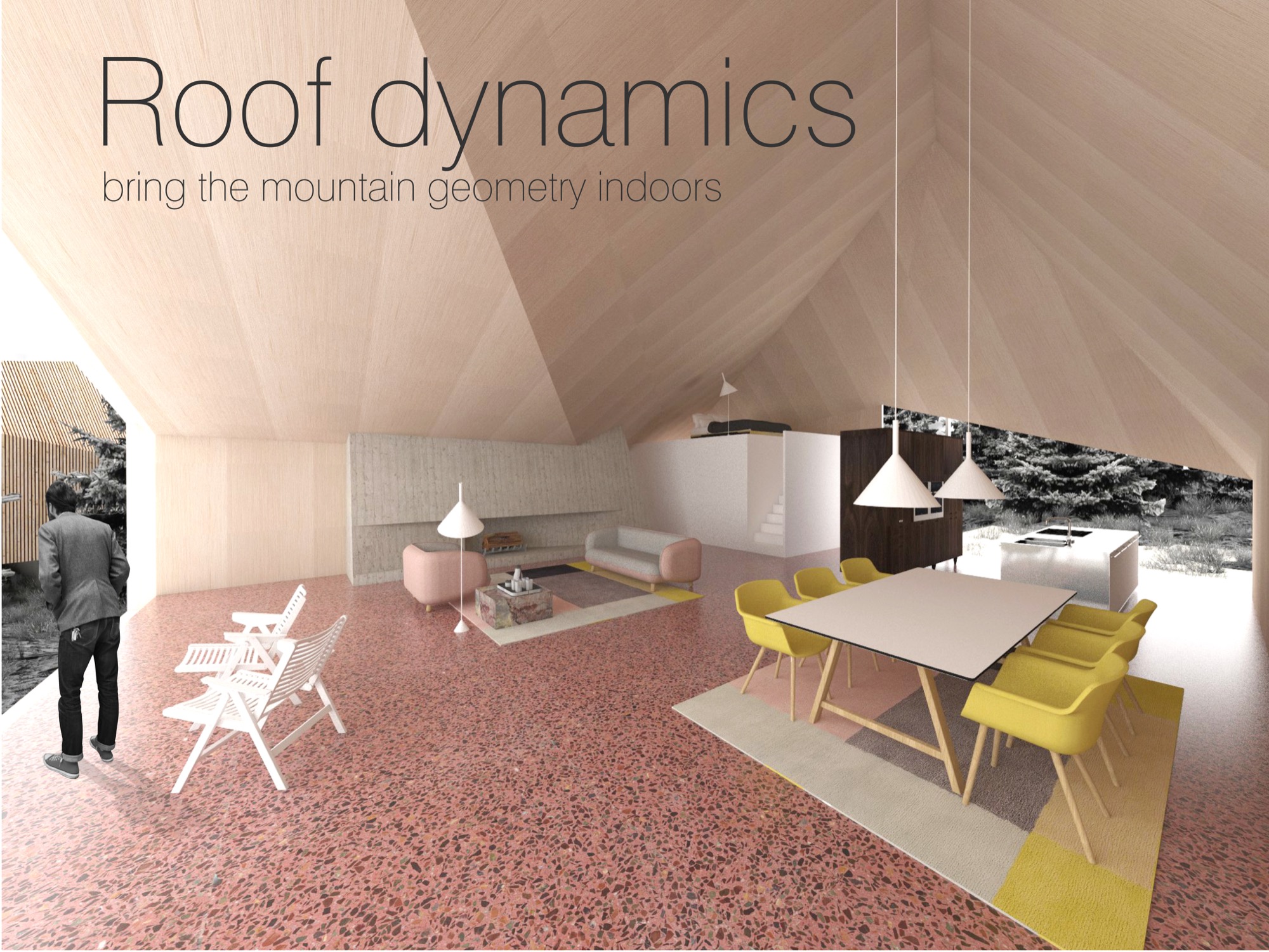

His proposed cabin design preserves that tentlike lightness and unmistakable functionality that inspired him and manifests it in a permanent, habitable structure. The architect expresses this lightness through a 1.5-inch (3.80-cm) thin “skin” made from cross-laminated prefabricated wood panels, folded to create the interior space of the cabin. This folding process leaves open the sides, which are then covered in glass. Juxtaposing the transient openness of the folded skin, a monolithic stone chimney stakes the raised cabin, grounding it into the mountainside to create the permanence a tent lacks. The chimney’s body also houses the mechanicals. On the opposite side, the cabin leans on a deck that touches down to the ground. With only the chimney and the deck as supporting elements, the cabin’s footprint is small, making large earth excavations unnecessary. The triple-glazed glass walls let the sun heat the highly insulated interior. Rainwater from the sloping roof collects into storage tanks under the deck. The goal is for the cabins to be certified according to the European passive house standard and the American LEED standard.

The cabin design allows for different versions of the prototype, varying from a simple one-bedroom hut to a luxurious four-bedroom chalet. The blueprint foresees an open living/dining/kitchen area with a large fireplace. The high ceiling follows the geometry of the exterior roof, mimicking the surrounding mountain silhouette. “In all, it will be a fantastic place to come back to after a full day of skiing or a long summer hike,” the architect hopes.

Nađ’s minimalistic “wooden tents” are designed to serve as fully functional habitable structures without creating the feel of urban settlement on Powder Mountain, and they preserve the essence of the natural surroundings. Nađ strove to convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out your private piece of paradise.

His sensible solution was, no doubt, spawned by his home country and culture. “We are really humble, hardworking, and resourceful people. So that guides me to find simple, functional, and long-lasting designs for my projects,” he says, adding that the alpine cabins and shelters of the Slovenian mountains influenced his “wooden tents” for Summit Powder Mountain. “They are simple, rugged, but still graceful in unforgiving nature.”

Nađ didn’t plan to enter an architecture contest at the time he learned about the MAP design competition on an architecture blog. But the subject—a cabin—intrigued him since he thought it rather uncommon for an international contest. “You usually have a competition to design a museum, library, memorials...but houses are rare.” The premise of Summit Powder Mountain eventually compelled the young architect to enter his design. “You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.” However, he didn’t grasp the expanse of the project until he spoke with the Summit team. “I didn’t realize how important this is for the global community, as it shows a new way of planning large developments,” he says in retrospect. Nađ understood that no matter how good his cabin design was going to be, simply copying it 500 times would only create the type of cookie-cutter development that already characterizes too many mountain resort towns. “My design goal was to create a house that can be transformed—enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, have a different facade—and still preserve the overall design idea,” he explains. The “wooden tent” concept is a suggestion, one Arthur says is “a loose design that’s poetic and evocative.”

“You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.”

Building community

Summit is breaking ground this summer to build the first cabins on Powder Mountain. Furthermore, the company is planning the new alpine village, with shops and galleries, coffeehouses and restaurants, gathering venues, condos, and new headquarters for the ski resort they acquired. Arthur thinks seasonal skiers and hikers may visit the mountain and never know about Summit’s quest for settling an art, culture, and tech elite here, though it seems hard to imagine tourists coming to this creation of an idyll and doing their own thing. “We’re based on gathering,” Arthur emphasizes. “People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

“People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

What does new mountain architecture look like, act like, feel like? Only after winning did the architect from Slovenia realize how important his design was for the global community. In fact, Arthur argues that the encouraged culture of sharing is just another expression of Summit’s tacit broader understanding of sustainable living. “This isn’t ostentatious.” He points out that most members of the Summit Powder Mountain community would actually prefer to minimize their footprint by operating in a shared social space. “Rather than building large bathrooms and kitchens in their own house, people go home to sleep and to entertain a smaller group of people. Then they go out into the larger community spaces and venues to gather together. This is about collectivism and collaboration.”

But how do you curate a genial commune where strangers “gather in creativity” to become kindred spirits, collaborators, neighbors? You don’t. “We had a blunt policy for a while, a ‘no-asshole policy,’ ” Arthur reveals. In reality, they quickly came to understand that the Summit community fosters a quite self-selecting environment. “Basically, if you were obviously egocentric or self-centered, then you probably don’t belong here. People who want to participate and are ‘others-orientated’ and have the heart to expand goodness, usually work out pretty well,” he says. To the rest, it just doesn’t feel right to be there. The Summit leadership strives to strike a balance between public atmosphere and private, curated events. In the end, Arthur says, “It’s not an exclusive membership thing—it’s an overall public realm of creating a new mountain town.” △

The Architect Explorer

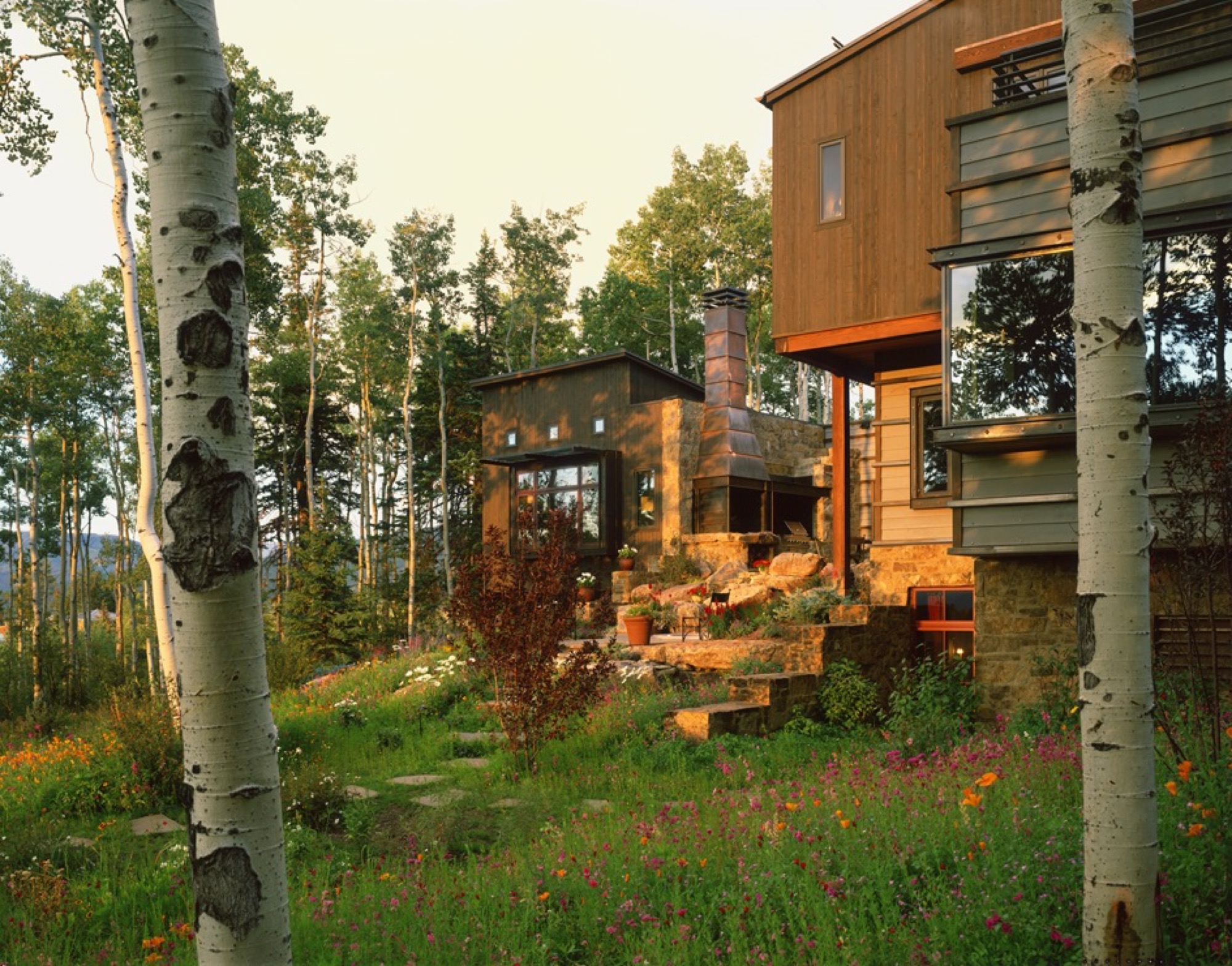

Colorado architect Larry Yaw interviewed by his journalist daughter

Colorado architect Larry Yaw, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, has nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond. An intimate conversation with his journalist daughter...

Sitting on a mossy rock in a tall stand of aspens next to my dad, a couple of hours into trying to find our way from Willow Lake back to the Maroon Bells parking lot, I started gnawing on my mom’s teriyaki beef jerky from my backpack. We had left the trail long ago, and I was convinced we were lost. I must have been about eight years old at the time.

“We’re not lost, we’re exploring,” is probably how my dad, architect Larry Yaw, responded—a claim that would echo through my young years as I followed him through the backcountry of the Elk Mountains in Colorado, across Kashmir in India, and through The Wind Rivers, The French Alps, New Zealand, and beyond, along with my mom and three siblings.

We got lost a lot, sort of on purpose, in the mountains. Yet never once did I see my dad flinch in these moments. Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul. I’d watch as he’d get this shrewd sparkle of excitement in his voice as he strategized on which ridge to follow, or which drainage would lead us back to the tent, all the while managing his family on the verge of the fearful discovery that our dad, really, had no idea where we were. Yet, now, as I bring my own young family into the woods to play and discover, I realize that my dad’s resourceful and poetic confidence that has intrigued me over the years has penetrated my own psyche deeply, and I strive to encourage that sensibility to seep into my kids’ sense of adventure. And, just as he did for our family, my dad has left an indelible impression on the contemporary design ethos of the Roaring Fork Valley, as well as countless alpine communities across the Mountain West.

“Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul.”

Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond, with an exceptional roster of clients and creative business partners as his co-conspirators; and he propelled them towards the outer edges of what’s possible. If I were to guess, his clients might sum up his character with a story similar to mine, yet the chapel would be his drafting table, and the map would be the radical ideas he has hand-sketched on camel-colored paper for the artfully crafted architecture he has envisioned. Sure, during his forty-six years creating innovative designs in the mountains, his aesthetic has shifted and grown, but his passion for the rawness of the backcountry, and for the purity of connecting people to place and to nature has remained firmly in tact.

“Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond.”

As his youngest daughter, I knew all of this, sort of, but it wasn’t until we had this conversation that I truly understood the gravity of how particular vignettes throughout his life have justified, and even come to imprint themselves, on his design, his spirituality, and his personal approach of getting lost—before finding a path.

Herein lies our recent sit-down at the kitchen table, an intimate chat between an architect and his daughter:

LYR How has living in the mountains influenced your design?

LY I’m the guy who can’t stop myself from climbing up and looking to see what’s on the other side of the ridge, or from going up to the end of a valley to see what’s there. If there’s some association with exploring, and innovating beyond the expected, I’m in. Therefore, my lifestyle has been defined by, and inspired by, active outdoor living, and attached to that is the adventure of it. Adventure is a part of everything I love to do—physical, intellectual, and spiritual adventure. And, therefore, I’ve begun to regard the artform of architecture as a basecamp for this; a basecamp that is sustainable, economic in scale, but very much connected to nature as that is so much a part of the adventure of being alive and in the now, wherever here is.

“Adventure is a part of everything I love to do ... I’ve begun to regard architecture, or habitation anyway, as a basecamp for this.”

LYR Who influenced you as an architect?

LY First, the biggest influencers have been great clients of a contemporary persuasion, who relish the process of exploration and testing. There are other architects also, such as Romaldo Giurgola (“Aldo”), The Dean of Columbia School of Architecture, where I completed my Master’s studies. He would sit down and talk in these simplistic terms about the choreography that you create architecture through; the path you take and how that enriches you, and enriches the purposes of design. Louis Kahn—his work and writings inspired me.

And, the firm Morphosis Architects creates fabulous, courageous, contemporary, sculptural, and adventuresome architecture. As you traverse their spaces, you’re taken through them with this marvelous, layered, spatial experience that therefore inspires the choreography of getting from here to there.

LYR What’s your experience of being a modern architect in the Roaring Fork Valley, where opulent traditional mountain architecture is so dominant?

LY There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things. Even though I’ve been involved with opulence, I design around the expectation that you don’t let the house own you. And, now, there is a cultural shift toward an awareness that we have to be stewards of the land, and be mindful of not writing out a big order for the resources. That shift has brought clients who want thoughtfully crafted, understated, simple in form, and more directly responsive design.

"There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things."

Also, a townscape is really a library of cultural expressions over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time. Hopefully, what I do is an expression of my times and this culture, and doesn’t grab a crutch out of architecture’s past. Because the work of my firm significantly influenced the evolving character of architecture in the New West, I was elevated to the prestigious College of Fellows (FAIA) by the American Institute of Architecture. Our working mantra of design is that of “place-making” where architecture and nature are seamlessly integrated to the betterment of both.

“A townscape is really a library of culture preferences over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time.”

LYR You were raised in rural Montana. What did that upbringing impart to you?

LY Growing up in Montana, I really experienced these rural ranch and farm compounds that were formed over generations. They were always designed by the simplest means, in simple forms, and they seemed to sit respectfully on the earth. When I started studying these things, I discovered that they were really forms that described contemporary architecture in their simplicity. They were formed in protective surrounds, and were organized around working proximities, yet there was always a place for enrichment, like a little garden near the front porch. Then, these compounds grew organically—out of inelegant purpose, and rural rationality. I didn’t appreciate it then, but as I studied architecture, I started pulling out of my experiential self, and those things all matched up—that is contemporary architecture. It did not tread heavily on the land; it embodied economy of means; it had simple forms and echoed its context—all things that are generationally taught or experientially taught. They solved problems there, out of their own devices and their own means.

LYR How has design carried into, and impacted, other areas of your life?

LY It has opened my eyes. When I travel, I see different things; I wonder about them; I take them in. And, what I’ve learned is that I like evocative things. Evocative means you hate it or you love it but it nevertheless stirs emotion in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind. And, that’s true in architecture. The creative process and everything associated with it; the people you work with and the collaborations—they fuel my worthwhileness and my sense of adventure.

“I like evocative things…. You hate it or you love it but it stirs something in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind.”

LYR Tell me about the Blackfeet Indians, a tribe you became close to when you were young, and their impact on you, your design, and your art.

LY When I was twelve years old, I went to Browning, Montana, in the middle of the Blackfeet reservation, and there sat this gorgeous little Indian girl. She was about my age, dressed in a traditional beaded, white doeskin dress, and I was enchanted. Her name was Virginia Home Gun. That enchantment turned into a friendship with her. It turns out that her father was the chief of the Blackfeet Tribal Council. Over time, through traditional ancient ceremony, they made me an honorary member. That really stirred me. It continued beyond that, and I started reading and studying about the rituals and legends that were the spiritual glue of their life. The Blackfeet regarded themselves as a creature of the earth, and they understood the balance of their needs with earth phenomena. They would give thanks to the buffalo, and honor a slain enemy for valor. For me, it went from the idealistic warrior image when I was young, to understanding their spiritual nourishment that kept them who they are. That translated to me later on into a series of paintings that I call “Once Proud.” That’s my way at this point in life of telling the story of westward movement and how it maimed the spirit and freedoms of our native inhabitants of this place. This made us feel sort of culturally guilty and I was inspired to tell that story.

LYR What is the status of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley, and what role did you play in getting modern design where it is today?

LY Aspen has always been a place that embraced aesthetic adventurism, or tolerated it anyway, and has always fostered intellectual and artistic courage. My firm, my partners, a highly talented thirty-some staff, and our clients have allowed us to be one of the forerunners of the movement here. Personally, I haven’t pushed modernism [in the valley] for recognition; we have had clients and circumstances that permitted that kind of solution and character. But within my firm, I’m known for pushing beyond the expected, and going to a higher level of art form and different level of expression; questioning, pushing, improvising, and going beyond even what clients want. Straight competency in architecture is a mid-level solution—I advocate for artfully courageous and innovative solutions that are bigger than the problem.

LYR Who are the people who want modern architecture in the mountains? What makes them different from the “typical” client who wants that enormous heavy log mansion that says, “I have a lot of money, and I live in Aspen?”

LY Some people are here because it is a new bar on their reputation epaulette. The people who I gravitate towards, or who gravitate towards our firm, are here for reasons I’ve sorted out—for the adventure, the backcountry, and things that support our minds, bodies, and spirits. These are all truly good characterizations of our lives, and our personal culture. To put it into context, I’m not going to design three little sitting areas around the master bedroom so you can sit inside all day. You get out of bed, you have breakfast, and you go ski; you get out there.

In that, a question I always ask is: Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context? The answer is both depending on where you are, but it's a question I ask of it because its one of the beginning points that I use to align my sensibilities with those of a client or a place.

“Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context?”

LYR You get lost on purpose, in a way, right? How has this personal quality informed your design sensibility?

LY Freud said that problems couldn’t be solved by a consciousness that created them. In other words, you cannot solve problems where there are too many givens; otherwise you just spin inside the givens. Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost, I just feel like I entered another chapel as it engages another form of creativity, curiosity, and adventure in me. Being lost is inspiring too—when I was really young, out hiking and going to crazy places I’d never been, I marveled at earth forms, the magic to them, what got them there. As I went on, I studied geomorphology, and it all boiled down to tectonics of eruption, erosion, accumulation, weather, and all of nature’s will upon those things. It’s really compelling, and asks compelling questions, and I found some answers that I’ve portrayed in my painting.

“Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost.”

Nature can also help you appreciate your existence, be a stimulus for enlightenment, and fuel lifelong curiosities. As architects, we must embrace that kind of creativity and spirituality, the kind that enhances who we are, so as to create well being.

And, Lindsay, I can find my way back from anywhere.

A founding partner of Cottle Carr Yaw Architects, Larry Yaw has designed many of the firm’s award-winning projects—from resort and community design to corporate buildings and private mountain homes. In 1993, Yaw was named to the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows, the highest award given to the profession’s most respected architects. His projects are regularly published in architectural books and national design magazines.

Yaw received his Master’s Degrees in both Architecture and Urban Design from Columbia University and has since been a lecturer and design critic at several western universities. Believing in the importance of civic involvement, Yaw is also a founding board member of the Aspen Art Museum.

Architecture, Made On Site

The husband-and-wife founders of Scott and Scott Architects design-built their own off-grid cabin with the adventurous spirit of the powder boarders they both are.

Built by husband-and-wife architects for themselves, an off-grid cabin in the mountains of Vancouver Island captures the adventure and freedom of powder boarding, free of rigid ideas.

David and Susan Scott wanted to make architecture. But not in the way one imagines married architects making architecture for themselves — drawings of their dream mountain retreat, years in the drawer, just waiting for the right building site. No. Building their own alpine cabin, the Vancouver-based architects wanted to design and build in a singular act.

In 2006, a longtime friend led them to a piece of land he’d come upon when planting trees at 4,265 feet (1,300 m) above sea level, on the northern end of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. “We had never been on the snow in the area until acquiring the building site,” says David Scott, speaking for the adventurous couple. “We fell in love with it at first sight, and the people and terrain are really special.” With almost 50 feet (15 m) of annual snow accumulation, the remote community-operated alpine recreation area of Cain is known for legendary powder.

At the time, the couple, who met in architecture school in Halifax, Nova Scotia, worked for established firms and spent long hours in offices, drawing. “We have a love for building and being outdoors,” says Scott, who appreciates drawing as an important part of design. Now building their own off-grid cabin, however, they wanted to channel the freedom they feel when powder boarding into an immediate design process centered in adventure and not heavily in rigid plans. “We began the project with a desire to work with a greater level of freedom, where the specifics of the site and available materials would inform the work in a direct and unfiltered manner.”

Scott and his wife knew they had a narrow window in life, before having children, to complete construction on their own on long weekends and holidays, and with help from friends.

“We began the project with a desire to work with a greater level of freedom, where the specifics of the site and available materials would inform the work in a direct and unfiltered manner.”

Hand in hand: Design and construction

Inspired by the materials available around the site and the environmental conditions, construction was planned to avoid machine excavation, to withstand the very deep annual snowfall, and to resist dominant winds. Accordingly, the structure was elevated above the height of the accumulated snow on the ground. “The use of full-length, unsawn logs provided us with the ability to get height in a manner that used the wood’s strength the same way Douglas fir spar poles are used as sail masts,” Scott explains.

The cabin, primarily constructed from Douglas fir, gets more refined from the outside in. The columns are unworked logs, the beams and joists are rough, bandsaw-milled, and the walls, floors, and ceilings are clad in planed boards. The cabinetry is made from construction-grade fir plywood. The exterior is clad in cedar that has weathered to the tone of the surrounding forest. Both woods are harvested in the area.

The roof form began with a simple gable, rotated to direct the snow off the back of the cabin. A half-dormer was then introduced over the entrance to direct snow away from it, funneling the snow into the prevailing winds.

Family life at the cabin

Today, childhood memories are already being made at the cabin. The Scott family now includes two young daughters, who Scott says are both on skis and love the snow.

Much of the approximate 1,075-square-foot (100-sq-m) cabin’s interior is designed and made by Scott and his wife. The main living space is small, and the family spends much of the time on the long, cushioned bench eating, playing games, and relaxing from a day on the snow. “Our favorite spot is by the large window,” says Scott. “Both for the ever-changing view of the forest, but also in appreciation of the effort that went into its installation.” He drove the glass overnight on a rented flatbed and hand-positioned it with a group of friends the next day — “an incredibly smooth effort, given its size and weight.”

The remote site is directly accessible by gravel road five months of the year. During the other months, equipment and materials are brought up by toboggan. There is no electricity, and a wood stove provides the heat. Water is collected from a local source and carried in. The Scott family cherishes the simple lifestyle the mountain hideaway affords. “We enjoy the solitude of not having cell phones and gadgets around to distract us,” says the architect, who finds “a wonderful freedom” in seeing no bars of coverage on his phone. “This is an incredible place for our daughters to love being in the mountains as much as we do.”

“This is an incredible place for our daughters to love being in the mountains as much as we do.”

The powder hounds come up here as many weekends as possible during the winter, but they also love the warmer temperatures in spring when snow is still plentiful. “It’s incredibly peaceful,” Scott says. “The fall is fantastic when the blueberries are ripe, and we try to spend Thanksgivings on the mountain, splitting wood and enjoying dinners with friends.”

Adventure by design

The off-grid cabin was David and Susan Scott’s foundation project and formative in their desire to start their own architecture practice, Scott and Scott Architects, with the goal of spending more time in the mountains. To both, making architecture on site is ultimately the most direct, enjoyable way of working, and one that provides the greatest opportunity to understand materials and detail resolution and evolution. Today, the firm is working on projects in Whistler and Squamish, and in their province’s interior high country. “We love working in these challenging locations where adventure is the reward,” says Scott.

(Alpine Modern has covered the A-frame cabin Scott and Scott built in Whistler for a young family of skiers and snowboarders.)

What’s Inside?

Architect David Scott opens the door to the off-grid snowboard cabin he built with his wife on Vancouver Island to show his three most treasured artifacts hidden inside.

The cast-iron pot

“We have a Björn Dahlström-designed cast-iron pot we slow-cook many meals in on the wood stove, which is essential to how we live when we are [at the cabin].”

Get your own: Björn Dahlström designs pots and casseroles for the Finnish company Iittala. Dahlström’s current line is stainless steel, but cast-iron pots and Dutch ovens similar to the one in the picture are available from brands like Le Creuset, Sur La Table, and Lodge.

The splitting maul

“I have a love for Swedish axes. Of my collection of over 100, the most used and loved is the Gränsfors Bruk splitting maul, which powers through the yellow cedar rounds. It is a beautiful object from a company we greatly admire. Whenever cutting wood, I look at the stamped initials of the smith that made it, with appreciation for his work and respect for a very old company which values and celebrates the workmanship of the individuals within it.”

The Gränsfors Bruk splitting maul’s head is heavier than the head of splitting axes, and the poll is designed for pounding on a splitting wedge.

The blanket

“We love our Hudson’s Bay blanket, which was a wedding gift from the architect I worked for for a number of years, before we began our own practice. I’ve often thought that a Bay blanket should never be bought for oneself and is something that carries meaning as a gift.”

Buy it for someone: Woolrich offers Hudson’s Bay Point Blankets under the offcial license of the historic Hudson’s Bay Company. The legendary blankets have kept generations of trappers, hunters, fur traders, and Native Americans warm and comfortable. 100-percent wool, loomed in England. △

Love and Loam

An Austrian artist family makes rammed-earth architecture, stoves and raku tiles

Earthen materials bond an Austrian family of artists: The applied-artist father builds with rammed earth and the ceramicist mother and graphic-designer son create tiles using an ancient Japanese pottery firing process. All their work is deeply rooted in ancient techniques, yet their designs are expressively modern.

“Never.”

Trotting behind his father around countless construction sites, a teenage Sebastian Rauch convinced himself he would never follow in his artist parents’ footsteps.

Born this way

Now thirty and his hormone levels long balanced, Sebastian has succumbed to the truth: The love for elemental design, form, and earthen materials is in his DNA. His parents are ceramic artist Marta Rauch-Debevec and artist-builder Martin Rauch. She runs the tile label Karak; he heads Lehm Ton Erde (Loam Clay Earth). Together, they share a studio space in Schlins in western Austria’s Vorarlberg region, tucked between the German and Swiss borders and known for supreme skiing.

“Both my parents have art degrees and chose art as their livelihood,” Sebastian tells. “Somehow, it rubbed off on the children.” Today, he works as a graphic designer in Vienna. His sister, Anna Pia, is currently taking a maternity break from earning her degree in art pedagogy.

The son of two artisans admits that neither the material loam nor his father’s building sites interested him as a child. “I was all thumbs in construction, which led to a lot of tension between my father and me during puberty.” To his parents’ chagrin, young Sebastian preferred to spend his days in front of the computer. “I was engrossed in anything to do with science fiction and Japan, whereas my parents are much more down to earth, literally.”

Rammed earth

Sharing a studio compels the elder Rauchs to amalgamate their crafts. “Marta and I have been working in the same space together for more than thirty years,” Martin says. “In terms of materials and processing techniques, there are many synergies between ceramics and building with loam, which help us both realize our work.”

To the family, loam, clay, and earth symbolize the holistic philosophy inherent in their art: Loam represents craftsmanship and technology, clay stands for art and design, and earth embodies the sustainability of building with loam.

Martin, who sees himself as an applied artist rather than an architect or designer, is known beyond the Vorarlberg region for practicing the ancient technique of compressing loam into a distinctive building material as sturdy as concrete. His desire to architecturally design with earth grew from his early work as a ceramicist, oven builder, and sculptor. Today, he focuses on the aboriginal rammed-earth technique, which he approaches with innovation. He builds entire buildings from loam as well as indoor components, such as wood-burning stoves, flooring, and interior walls.

The process of compressing soil is time tested. Parts of the Great Wall of China were constructed from rammed earth. “Being able to create solid, bearing walls from such elemental materials fascinates me,” Martin says. “It requires careful study of the material but also courage. For example, one has to be able to allow the erosion.” External rammed-earth walls facing the elements will lose some surface, exposing stones and leaving a pebbled pattern. “Once we can accept the erosion, we can recognize its many benefits,” Martin explains. “We must recognize that its water solubility is really the most valuable virtue of loam as a building material.” His structures are 100 percent recyclable, often using ground dug up during a building’s own construction phase.

“Being able to create solid, bearing walls from such elemental materials fascinates me.”

His building materials and techniques are deeply rooted in tradition, yet Martin’s designs are expressively modern. “This very juxtaposition inspires me,” he says. “With the emergence of modern building methods in the last two centuries, building with loam was rarely considered, downright superseded, and degraded to the poor man’s building material.”

The Austrian artisan, who is currently cladding Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in rammed loam, is confident that quality modern rammed-earth architecture with progressive, adapted techniques can once again valorize the image of building with loam.

Climate control

Breaking new ground in sustainable building spurs Martin’s creativity as artist and craftsman. “I love developing new ways of contributing to an anthroposphere that is more conscious of the environment and mankind,” he says. “Loam as building material is pure inspiration.”

Loam is available as local material almost anywhere in the world, meaning short, to no, hauling. “About 80 percent of our own home’s building material, for instance, came from its excavation pit,” Martin says. High efficiency and low primary energy are further benefits inherent in rammed-earth buildings. Locals identify with his work for these sensibilities. “It’s not unusual for our projects that the principal or the villagers join in building.”

Bringing the rammed-earth technique into the twenty-first century is a challenge the builder approaches from a business standpoint. “In Europe, it is important to react to the rationalized and industrialized building sector,” he explains. “For us, the prefabrication of rammed-earth components plays an integral role. It allows us to build much more efficiently and according to today’s construction timelines.”

Rammed-earth interior walls promote a well-tempered indoor climate. The enormous mass abates temperature extremes and superbly regulates humidity. If you have eaten a Ricola herbal cough drop, you have a connection to Martin’s work. He collaborated with Pritzker prizewinners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, founders of the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron Basel, on the Ricola Herb Center near Basel. Martin’s loam walls promote ideal humidity levels for storing and processing the herbs.

Haus Rauch

Though Martin has been working with rammed earth for more than three decades, the home he built for his own family was a test bed for further adapting and refining his technique.

The 200-square-meter (2,150-square-foot) home built into a steep southern hillside above Martin’s native town of Schlins was completed in 2008. The design was a collaboration with Zürich architect Roger Boltshauser.

In its orientation and form, the house directly speaks to the topographic flow of the site and the context of the landscape: A monolithic structure like a sculptural block is literally pushed out of the earth. The use of solid rammed-earth walls combines this architectural intention with the desire to construct an ecological building exclusively made of natural materials.

The mother of creativity

Marta, who was born in Ljubljana, Slovenien, and studied ceramics and product design at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, never urged her son or her daughter to work with her. “Simply following in your parents’ footsteps doesn’t bring you happiness. I wanted them to cultivate their own dreams and visions, so I never thought that one of my children would one day work with me.”

Having been an independent artist working on theme-based projects for exhibitions and sculptural ceramic objects, Marta herself hadn’t planned on specializing in tiles. But she knew she wanted to incorporate ceramic art in the new house.

After working with a low-fired technique known as raku, a traditional Japanese pottery process, for twenty years, Marta wanted to explore tiles as medium. “I was looking for a tile design for the house when I discovered the beautiful patterns Sebastian was creating on his computer,” she remembers. He says he created the designs “just for fun.” Marta wondered how she could transfer her son’s digital doodling to her tiles and began experimenting with screen printing. “When I created the first samples, we were all surprised how stunning the combination of the raku tiles and Sebastian’s patterns truly was.”

“I was looking for a tile design for the house when I discovered the beautiful patterns Sebastian was creating on his computer.”

Karak tiles

The Karak brand was born. Marta and Sebastian’s Karak tiles—each a unicum—embody the elementary relationship between the Eastern and the Western world. Captivating geometric ornaments, the result of repeating, digitally created design patterns, are married with the century-old Japanese raku technique that gives the tiles an inimitable air of chance.

The tile material is a combination of different kinds of clay and loam mixed with quartz sand and fireclay. Pressed into shape, each tile is retouched by hand, the designs applied by silk-screening.

As the tile is red at about 1,000 degrees Celsius (ca. 1,830 degrees Fahrenheit), the material’s transforma- tion becomes palpable—the low-fired technique makes it porous and gives the final product a deep, organic sound at the touch and a warm haptic.

Still glowing, the tiles are removed from the kiln one at a time and immediately hermetically buried in sawdust. The void of oxygen and the smoke have an intense effect on the surface that varies for every piece. The color changes with the glaze; hair-thin cracks are blackened.

Finally, dunking each tile in water reveals its finished character. Transformed by the temperature shock, the glazed surface is brushed off, evincing a craquelure—like a fine net tying everything together.

Starting Karak wasn’t a conscious decision but rather a mother-son collaboration that grew organically. At first, the two intended to create the tiles only for the family’s villa. Then a book was published about the unique house. “On occasion, people began talking not about the Rauch house but about that house with the beautiful tiles,” Sebastian remembers. “People were asking us where we got those tiles...that’s when orders began coming in.”

“When we created the tiles for the house, I suddenly knew the charm of these tiles,” Marta says. “After all these years, I am still excited every time I walk in the door.”

Futuristic fantasy meets ancient technique

Sebastian’s passion for science fiction inspires the patterns he designs for the tiles. “I love to connect antipodes, things that seemingly don’t go together, the interplay between contrasts...that tipping effect.” His KuQua design, for instance, combines spheres (Kugeln in German) and squares (Quadrate). “When you deconstruct these two shapes and recombine them, they become almost unrecognizable in an entirely new shape. However, there is an underlying geometrical clarity and calmness that makes me feel like I didn’t design this shape; rather, I found it. At the same time, there is constant movement as the eye meets the pattern, like a deep mantra lancing the universe, like yin and yang.”

His mother is no less fascinated by the repetitive geometric patterns’ tipping effect. “Depending on how the eye focuses in, the design can suddenly appear three-dimensional,” she says. “In fact, we created a three-dimensional tile, the TaOk tile, a tantalizing combination of modern geometrical design and something Oriental. Then, the ancient technique adds something very primordial...a beautiful enrichment.”

The raku process gives a brand-new tile the patina of a long life. “I am intrigued by something that looks so archaic, yet you can’t really assign the object to an epoch,” Sebastian says. “I like to envision an archeological excavation site where they dig out a temple and find patterns and artifacts that don’t have a place in our past, in the human past...so you may have discovered an alien temple.” The precise patterns, the exact geometry combined with the serendipitous process make Sebastian optimistic for the future. “In science fiction the future is often depicted as extremely slick and clinical, as measured and constructed. I rather like the thought of a future that is still sensual and vivid.”

The geometric patterns are calculated and carefully designed, with precise lines. But the firing process, the smoke passing through the tile, and finally the quenching in water is so incalculable that what was once smooth becomes structured, what was once superficial gains depths. “It is a movement between order and happenstance, between repetition and uniqueness,” Marta adds.

“It is a movement between order and happenstance, between repetition and uniqueness.”

Both Marta and Sebastian appreciate the synergies and new opportunities that come with sharing the workshop and resources with Lehm Ton Erde, particularly Martin’s tinkerer skills and powerful imagination.

“Growing up, I was pretty sure I wanted nothing to do with loam,” Sebastian admits. “Funny how I found my way back to the material.” In the end, he’s grateful his parents laid the groundwork. “I couldn’t imagine working like this if it weren’t for being a family.” △

“I couldn't imagine working like this if it weren't for being a family.”

Haus Z2 in Bayrischzell

The modern vacation home by Beer Bembé Dellinger reinterprets traditional Bavarian-alpine forms and materials

The large glass façade in the front and glass oriels on both sides of the house ensure a scenic view from the foot of the Wendelstein down to the valley from almost every room. The house's oblongness is inspired by the Alps and represents a reinterpretation of the characteristic traditional Bavarian barn. At the same time, the design concept addresses the site's narrow proportions.

The house's materials are also influenced by Bavarian-alpine traditions — mainly larchwood in form of tongue-and-groove boards for the façade and as shingles on the roof.

Lead architects were Felix Bembé (conception) and Michael Wondre (project leader and construction supervisor). △

Hideaway Cabin

Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta in Norway

Seemingly growing from the mountain, the impossibly small Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta shelters up to 21 people. The Norwegian firm Snøhetta creates architecture, landscapes, interiors and brand design. And in this case, incredibly small architecture with a big task.

Family shelter

The project was commissioned on family farmland by Osvald Bjelland, who is chairman and CEO of the global business advisory Xyntéo and founder of The Performance Theatre, a leadership think tank.

The challenge in designing the Åkrafjorden hunting lodge on a fjord, high in the mountains above the village of Etne in Hordaland, Norway, was indeed its small size in the face of its intended use: The mountain hut was to be maximum 35 square meters (ca. 377 square feet), with the capacity to shelter up to 21 people (the same number of beds as at the family's farmhouse down in the village). Plus, the off-grid structure with no running water needed to look like it had always been there.

Only accessible by foot or on horseback, the remote lodge’s setting is beautiful, isolated, beside a lake in the untouched Nordic wilderness of West Norway.

One important part of the design concept was to integrate the hut into the landscape. Thus, the small hut’s shape, orientation and materials are influenced by the terrain’s characteristic composition of grass, heather and glacial rocks. In winter, the cabin becomes another brown fleck — like the rocks — in mounds of snow.

Modern expression of ancient traditions

The structure consists of two curved steel beams, covered with a continuous layer of hand-cut logs of timber — a fusion of modern architectural expression and the style of traditional Norwegian mountain cabins. The roof, with its organic form, “grows” out of the landscape and is overgrown with grass. The materials of the facades are local stone, tar treated wood and glass.

To make room for a surprisingly large number of guests in such a tiny space, the architects found inspiration in ancient lodging traditions: The space in the center serves as gathering place, and the beds along the walls provide a spot to sit comfortably around the middle of the room in the evening — one piece of furniture for socializing, eating and sleeping. A narrow nook by the entrance accommodates cooking equipment and storage. △

Trollstigen Visitor Center Norway

Designed by Reiulf Ramstad Architekter, the visitor center and viewing platform dramatically enhance the experience of Norway's wild nature and landscape.

Oslo-based Reiulf Ramstad Architekter (RRA) has a reputation for bold, beautifully simple Scandinavian architecture — from groundbreaking civil buildings to private Nordic holiday lodges — all bold and unhesitating in form yet free of pretense in their assertion in the landscape.

Alpine Modern has previously covered one of Ramstad's residential designs, the V-Lodge.

Now, German photographer Lars Schneider of Outdoor Visions shot one of RRA's public works for us, the Trollstigen Road Visitor Center. Opened in 1936, the Trollstigen National Tourist Route stretches 106 kilometers (66 miles) through West Norway's mighty nature. Ramstad's firm designed the visitor center to enhance the experience of rugged mountains, waterfalls and deep fjords.

Lars Schneider's report from the road

"I was on assignment in Norway, shooting for an outdoor clothing brand. The night I captured these images, after the client and the models had left for the hotel at one o'clock in the morning, my assistant and I decided to spend the rest of the night in the mountains. The sky looked promising, and the sun rose at 3:30 am that time of year.

"We lingered around the visitor center for a very long time. Besides taking in the spectacular views and the sensational light, we quite enjoyed the fact that we had all this to ourselves. During the day, droves of tourists swarm Trollstigen, eager to take tight hairpin turns winding up and down the steep mountainsides and to take in the untamed Nordic vistas. Not having to share all this with anyone was immensely gratifying.

"The architecture is grandiose. Everything very sophisticated, rectilinear, pure, considered... yet beautifully assimilated into the scenery." △

Context and Contrast in the Alps

An Austrian vacation home’s design references its mountainside setting and expansive views across the valley

The 106-square-meter (1141 square-foot) home’s design is based on a flow of rooms that follows the terrain’s slope and an open floor plan organized on three levels. Covered loggias extend the living levels upslope and downslope, creating interfaces with the alpine surrounding. The black wood structure confidently makes its mark in a heterogenous setting.

The client’s program for this vacation home near Zell am See in the Austrian state of Salzburg was simple: a great room with integrated kitchen and dining, sleeping quarters with an en-suite bathroom for each bedroom, a guest suite, and a covered outdoor space that offers mountain views from morning until evening. A carport and practical storage spaces were to round out the project.

Design trilogy

The design by architect Thomas Lechner, principal and founder of LP Architektur, is organized in three areas: arrival, function and living. Positioning the house in the context of building on a mountainside with majestic views as “counterpart” was of the essence.

The first area — arrival — is situated directly down by the street, with a carport plus storage room as prelude. Ascending to the vacation domicile, long stairs coil near the top and reorient the visitor toward the valley and the surrounding mountains.

The entrance to the house creates the interface to the second area — function — with functional spaces on one level. One has arrived, may want to hang up his or her coat and perhaps use the powder room.

Passing through the space dedicated to the arrival, the interior opens to the third area, the great room, which is arranged and organized in three levels that follow the slope of the mountainside. Single flights of stairs connect the living levels. Kitchen and dining are in the center, a fireplace area below and a space to read above. The grading creates each area’s back, providing a sense of security. Despite the spaces’ connectedness, each level is differentiated by its distinct formulation. The center area is dominated by the view out the window dominates, with the mountains as theme, like in a painting on the wall. The levels above and below, however, can be interpreted as interfaces to the outside, with covered loggias extended each respective room to the outside and opening it up into nature. The open-sided rooms offer a protected space for being outdoors during its assigned time of day. The level with the fireplace thematizes the relationship to the surrounding mountains and the panoramic views, while the reading level signifies retreating to a confined space in reference to the immediate surroundings.

The main living area leads to the north-east-facing bedrooms, each with its en-suite bathroom, which then also belongs to the house’s function part.

Compress and release

The house’s overall concept comprises a variety of spaces and rooms, each offering distinct individual qualities. Depending on needs and mood, one can retreat, disappear, feel snug. Yet the home also offers opportunity to experience the expanse and freedom of the alpine landscape unfolding outside.

This contrast, the polarity, is also reflected in the choice of materials. Painted black on the exterior, the timber structure confidently claims its space within its surroundings. By contrast, the light, warm interior affords a comfortable environment where one can relax and recharge. △

Narrow Escape

Falling in love with an impossibly narrow lot on a mountain village's main street, A Denver architects builds a 15-foot-wide weekend home for his adventurous family

Incited by a seemingly impossible building site in an old railroad town above Vail Valley, Colorado, a Denver architect designs a 15-foot-wide sustainable mountain getaway as a speculative investment for sale. Then his adventurous family falls in love with the home. It was an eyesore. Passersby merely saw a ramshackle trailer overstuffing the 25-by-100-foot (7.5-by-30-m) lot on Main Street in Minturn, Colorado. Yet, André Vite spotted an opportunity.

The campus architect at the University of Colorado Denver and his wife, Ginger Borges, an oncologist at the University’s medical school, have a weakness for obscure properties. That evening three winters ago, however, they maintain they were not scoping out a new venture at all. The couple and their preteen sons, René and Niko, were headed to the old railroad town up Eagle River for dinner after a day of skiing in Vail. “We drove through Main Street Minturn, which is a town we go to all the time, and there was a mobile home for sale that was just totally wedged in and awkward looking,” Vite remembers.

Even though he didn’t know what to do with it at the time, the architect wanted that piece of land. And he got it without difficulty because the city planners had been eager to get that blot off Main Street.

The draftsman went home and started sketching.

S(e)izing the Opportunity

The lot’s appeal was twofold: It was located right on the town’s main stretch and it was zoned for mixed use. “From a planning and zoning standpoint, it was a fantastic opportunity,” says the architect and urban designer, who also heads his own practice, the Vite Collaborative. (Or, as he describes it, “A bunch of friends working on unique projects together.”) If for nothing else, Vite purchased the property at a propitious time. The shops along Main Street had been expanding in that southern direction in recent years. Thus, Vite had originally designed the project as a residential spec home with the option for retail or commercial space on the ground floor.

While the sliver of land overlooks the principal artery of town life on the Main Street side, the opposing end couldn’t have more different surroundings — a quiet residential street with community gardens across the way. “From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building,” Vite recalls. “Both facades relate to the context of the side they are on.”

“From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building.”

Yet another challenge the building site posed was the 10-foot grade change between the two frontages — an entire story difference, front to back. That was not all. The town’s zoning laws required a 5-foot setback from the property line. The house could be only 15 feet wide.

Fortunately, the neighbor’s garden to the south and a driveway next door to the north give the narrow site extra breathing room. “It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light,” Vite says.

"It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light."

Unconstrained creativity on 15 feet across

The building constraints — the narrowness, the contrasting major facades, the steep slope — only spurred Vite’s imagination and inspired innovative solutions. How did he create a modern living space — an entire three-story house — with 15 feet (4.6 m) across to work with? The architect’s answer was a structural steel frame, an element adopted from commercial construction, which gave him the structural freedom to engineer large open spaces on the inside. “It’s a steel moment frame structure with three beams that go all the way down the building. Then there is a steel beam across the top.”

The steel beams manifested what would become part of the narrow house’s legacy, and with it, a close relationship between Vite and the local builder, Brian Beckett. “When he was erecting the moment frames, Brian called me and said we can’t put the roof on tomorrow,” Vite says. One of the moment frames had been a quarter-inch off plum, which was still well within building tolerances. As might be expected from the sanguine architect, the holdup was anything but a point of contention; on the contrary. “To have a guy who takes this that seriously was just really important to me. I knew I was going to get a great building from him,” says Vite. “The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

“The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

Actually, there was one moment during construction that did stop the architect in his tracks. After Beckett put the roof on the now-perfect steel frame, he took a picture and sent it to his client in Denver. “It looked like a tube; like you wouldn’t ever want to live in anything like it,” Vite remembers his initial reaction. “It wasn’t until we started finishing it out that it turned into what we’ve got. But that was a scary point, because it was so narrow.”

Family first

By the time construction was completed, the next ski season was approaching. Vite and his family had frequently driven up from Denver to ski in the Vail Valley during previous winters. “We decided we would use the house for that ski season,” Vite says about the investment property he had just finished. “We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

“We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

The unique house itself wasn’t the only reason the family never wanted to move out. “We absolutely fell in love with Minturn. It’s the real authentic mountain community between Beaver Creek and Vail, where you have all these people who are transient and vacationing. The people in Minturn are really the ones who keep that valley going,” says Vite about the mountain town’s thousand or so residents.

What’s more, Borges not once considered her husband crazy for building this improbable house. “We’ve been married for twenty years,” Vite laughs. “She is used to that.” And attuned to narrow dwellings she was. The first home the couple restored and lived in together was a townhouse in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood that was only 14 feet wide. “She’s getting an extra foot,” Vite exclaims, insisting his wife was thrilled about the idea to keep the Minturn house. Now the four escape up here nearly every weekend, year-round, to fish, drive their go-kart, hike — or ski in winter.

Open space to monkey around

Since completion, the house has evolved into a fun destination in its own right for the adventurous family. “The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open,” Vite says. Scarcely any interior walls partition intimate bedrooms and private bathrooms from the open, free-flowing floor plan. At the bottom, the concrete foundation encases a below-grade guest bedroom and bathroom on the dwelling’s Boulder Street side. Because of the steep slope, the opposite end is above ground, where the garage faces Main and can be extended out to the street for a future retail space.

“The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open.”

The ceiling of the modern living room on the second floor rises two stories with an overlooking loft, the parents’ open bedroom. The boys’ west-facing bedroom is tucked behind the “master” (or in front of it, depending on which frontage you interpret as the face of the house).

The family spends most of their time together in the open living space with the curved white couch. “We take this big picture off the wall and project movies onto the wall.” The cork-floored main living area flows outside through a folding glass and steel wall that opens up to the deck. A minimal dining area in the middle transitions into the kitchen, Vite’s favorite spot in the house.

“But what the kids love is this 26-foot space here,” says Vite, pointing at the high living room ceiling, where he mounted a climbing rope. “They get to climb up this wall that’s all blocked with wood, ready to put in finger holes for a climbing wall.” Climbing is indeed the boys’ favorite indoor pastime. “They climb everything they can get to,” their father reveals, pointing to a trolley that runs down the steel beam under the roof above the master loft. “You can strap yourself onto here and then push off.”

In addition to providing a place for the family to escape the city on weekends and holidays, Vite wanted to set the stage in the house for a few cherished vintage pieces he inherited from his late parents. “The interior design was all about finding a home for my father’s old furniture he had bought in the early sixties in New York. It’s all authentic midcentury-modern furniture, and I designed the interior around it.”

Sustainability as style

The LEED-accredited architect is reluctant to categorize the architectural style of his idiosyncratic house. “What they call it up here is a contemporary mountain home, because it very much has the feel of a timber frame, although it is done in steel,” he says. “But rather than talking about a style, the sustainability feature is more important to me.”

From the construction standpoint, the house is based on a standard wood module to limit material waste, which actually got Vite in trouble with one particular Minturn resident. “There is a guy up here who goes around the construction sites, picking up wood waste for his wood-burning stove at home. He would complain that we didn’t have enough wood waste and gave us a hard time.”

The carefully calculated use of exterior wood is to protect the building from driving rain in support of the actual weather barrier behind the wood. “All these gaps are open,” Vite shows. “It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.” Air exchange is critical for a highly insulated house at this altitude, where the air is extremely dry. “You are living and cooking and doing all these things that increase the humidity inside the house,” he explains. Instead of trapping the warm, very moist air inside, the house can breathe it out. Vite also installed a heat recovery air exchanger that pushes warm, inside-air to heat colder air coming in to ventilate the house, without using the heating system.

“It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.”

Vite received the 2013 Award of Citation from the American Institute of Architects for this project.

Tight house, tight Community

Being awarded such a significant professional accolade from AIA is nice, sure, but what truly warms the architect’s heart is how the locals perceive the standout structure they’ve come to call the “skinny house.” “We get compliments on it all the time. People are stopping by, saying they’ve watched it go up and want to look at the inside,” he says. “I love that the town loves the house.” △

“I love that the town loves the house.”

A Whistler A-Frame

Scott & Scott Architects design an outdoorsy Vancouver family’s dream cabin

If the multiple languages and accents overheard in lift lines and on gondolas tell any kind of a story, it’s that everyone from everywhere with a serious interest in skiing or snowboarding is making a beeline for Whistler Blackcomb. More and more of those visitors are putting down roots with a second home in this outdoor wonderland north of Vancouver, Canada. Some buy condos in the heart of Whistler Village or townhomes with ski-in/ski-out access to the slopes. Others build luxurious heavy timber colossi in swank residential areas that have grown up around the resort’s edges.

No matter their size, most of these mountain retreats share the following design elements: wilderness building materials, either structural or decorative, and floor plans and amenities that mimic those found in city interiors.

While there is nothing wrong with having a second home in the mountains that works much like a primary one in the city, some younger ski and snowboard families have begun to question why they would want to occupy such a space when a more indigenous—and much radder—alternative is available: an iconic A-frame cabin.

Return of a classic-modern icon

Ah the A-frame, that staple of mid-twentieth-century vacation home vernacular that was massively popular across the North American outback from the 1950s through the 1970s. There is no way this odd-looking triangle-shaped structure, which got its start in ancient days as a roof hut in Japan and a storage shed in Europe, could be mistaken for anything urban. Attempts in the sixties and seventies to make it a city building resulted in churches, fast-food joints, suburban houses and motels that were novelties even then.

The classic post-Second World War A-frame cabin was a purpose-built backcountry bolthole. Its simple construction, minimal building materials and absence of fancy finishes made it a preferred DIY project for Mad Men-era handy men, and in the 1960s, A-frame cabin kits sold briskly. Most of these ready-to-assemble weekend homes shot up in snowy locales.

One reason for this is the A-frame’s radical roofline that extends down to the ground on two sides, which helps shed any snowpack. Another is its ability to capture natural light. The A-frame’s roof supports all of the building’s weight, freeing up the gable ends to be filled with wall-to-wall glass.

A third reason for its easy fit in alpine terrain is one you might not have imagined given the A-frame’s modern, inorganic appearance. In this landscape, it can be a chameleon, a slender, weathered wooden form indistinguishable from evergreen trees.

For all of its baked-in virtues and utter lack of pretense, the A-frame is enjoying a renaissance. Outdoor types who value authenticity are enthusiastically rescuing original 1960s and 1970s models, hand-building replicas (check out the Urban Outfitters online journal for directions on "How to Build an A-Frame Cabin") or commissioning fresh versions that honor the building's honest materials and original intent, which is what Vancouverites Melanie and Brenton Brown did when they gave the go-ahead for the elegant update pictured here.

A family’s dream

For years, the outdoorsy couple and their energetic offspring, Daisy and Finn, now eight and 13 years old respectively, bunked off and on with close friends in their 1980s A-frame in Whistler’s Emerald Estates neighborhood. In 2014, the family decided to build their own variation on a property up the street from their friends. “We wanted a new cabin that would not look out of place with the older ones in this area,” says Brenton, CFO for the Vancouver-based digital commerce platform Elastic Path Software. “An A-frame felt like the perfect fit for us,” says Melanie, who is an interior designer. “It has a retro feel we love and, obviously, we knew what we were getting into with this type of building.”

Idiosyncratic Emerald Estates

If you wanted to build a new A-frame in Whistler, idiosyncratic Emerald Estates would be the right place to do it. It is one of Whistler’s early neighborhoods, dating to the 1960s when the community mainly consisted of diehard Vancouverites willing to drive 75 miles of nasty road on weekends to ski its pristine powder, full-time construction and seasonal workers, plus assorted ski bunnies and bums.

A-frames are at home in this neck of the woods where a lot of the housing stock still has a throwback vibe. Among its early Whistler building types, Emerald boasts classic 1960s, 1970s and 1980s A-frames and Gothic-arches cabins (their bulbous bow-sided brothers), Heidi-style chalets and quirky hand-built dwellings such as Whistler’s famous “Mushroom House,” where, if Emerald Estates were a fictional fantasy world, Bilbo Baggins would want to live.

Although it is only a 10-minute drive from Whistler Village, Emerald feels off the beaten path. It is still a neighborhood more associated with local families than visitors. Most of the residents are old-timers and full-timers, “not weekend warriors,” says Melanie, laughing to think that this label could be applied to her little tribe.

Emerald’s topography is steep and wooded, with winding roadways that dip to reveal the teepee peaks of A-frames poking out above treetops and that rise to expose wide-roofed chalets juxtaposed with glacial rock formations.

The Browns’ property is open, steeply sloped and pie-shaped: wide at the front and narrow at the back where a four-story-high granite outcrop dominates. The site is high enough up the hillside that the evergreen trees, so plentiful downslope, have no effect on the view. “It’s panoramic, an unobstructed 180 degrees,” says Brenton, pointing north to Weart and Wedge mountains with Armchair Glacier sandwiched between them, then south to Whistler and Blackcomb. The family’s new cabin, designed by David and Susan Scott of Vancouver’s Scott & Scott Architects, capitalizes on all of this scenery.

The Scotts and the Browns

The Scotts are a husband-and-wife team who worked independently for years for prominent Canadian architects before forming an architecture practice together three years ago. Their office/home, which they share with two young daughters, is a converted butcher shop in the Mount Pleasant/Main Street area, currently the coolest neighborhood in Vancouver for young families to live.

Every project the Scotts have completed together has received public praise and attention either in a peer review journal, a lifestyle magazine or on a discerning design website—and sometimes all three at once. This past winter, the Scotts were recipients of the 2016 Young Architect Award from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. It is the first time the society has given this award to a couple.

The Browns were introduced to the Scotts through architect friends who admired their work. After seeing images of the Scotts’ own off-the-grid cabin at the north end of Vancouver Island (it appeared in the inaugural print issue of Alpine Modern magazine), the Browns were smitten with the Scotts’ understated, minimalist design and use of traditional and off-the-shelf materials in interesting and diverse ways.

Elemental, accessible design is what the Scotts are known for. “No one ever actually says this to us, but I think part of our appeal is that what we do is not outlandishly opulent,” says David, “so we end up with young families who want a holiday place in Whistler or Tofino [the surfing capital of Canada] but aren’t into building grand statements.”

“What we do is not outlandishly opulent, so we end up with young families who want a holiday place in Whistler or Tofino but aren’t into building grand statements.”

Working all angles

The Browns’ new A-frame may not be a grand statement, but it is an eye-popper, and when you begin to look closely at the design, you can see that it is an extremely intelligent and refined evolution of a basic building type.

Take the roofline, the A-frame’s defining feature. On a flat site, the roof would sit directly on top of the ground with identical triangular gables at either end. The challenge for the Scotts was how to incorporate these archetypical elements in an innovative way on a steep site.

Their response was a three-story building, narrow at the back and wide at the front just like the shape of the lot, with different-size gables at either end and roof planes that follow the grade.

As with A-frames of old, the Scotts’ roof design is a declaration—but with a difference. Level at the top, the ridge has been pushed out beyond the front façade of the building, then the gables have been pulled back at an angle so that the bottom edge of the roof is now parallel to the slope not the ridgeline. Laying the shingles at this same gradient gives the roof its rakish appearance.

From the rear, the Brown’s cabin appears to be a single story defined by a slender gable tied, in classic A-frame fashion, directly to the landscape, in this case volcanic rock. What you are really looking at is the back end of the third floor, and the space inside is a den, which opens onto the generous patio the Scott’s fashioned from a flat space in the outcrop.