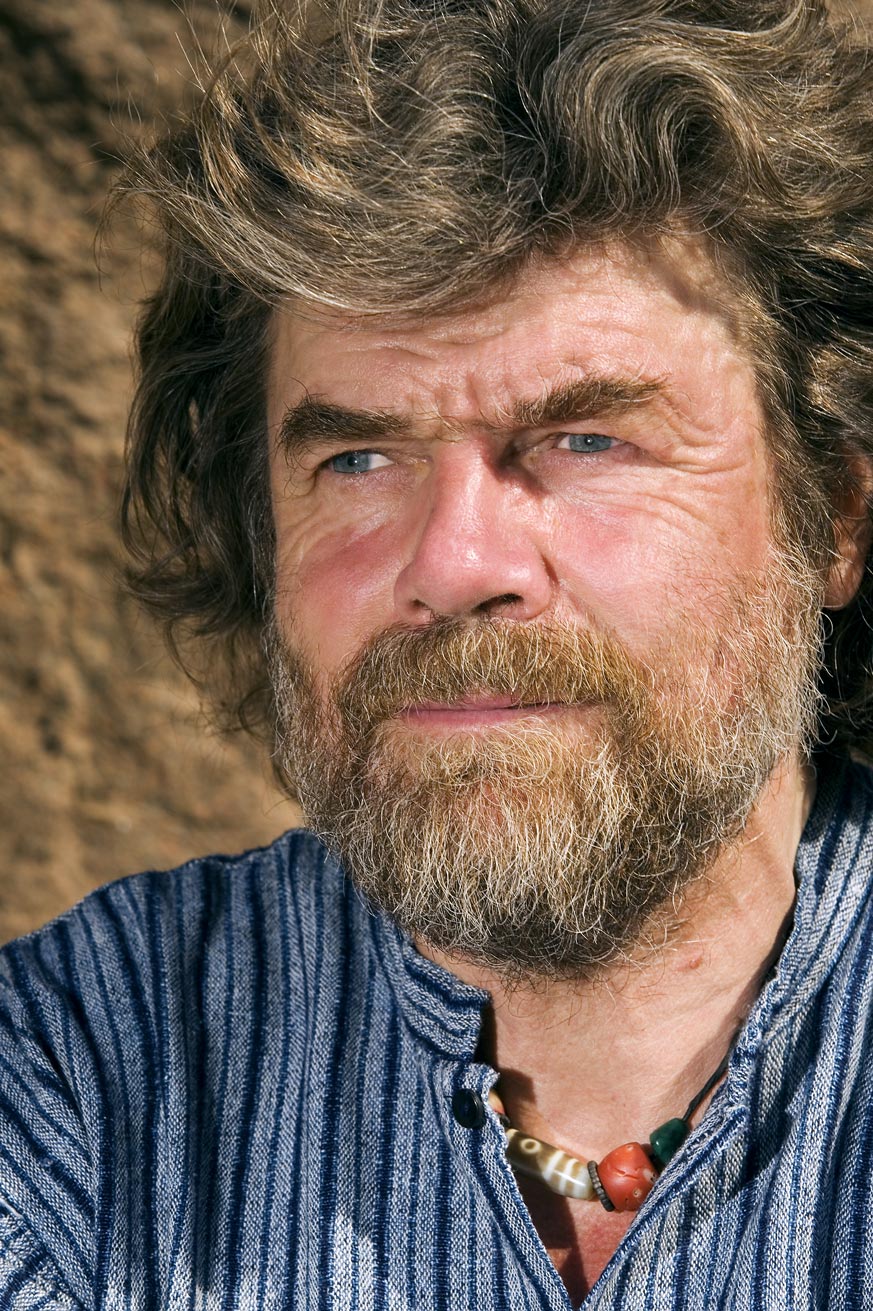

Reinhold Messner: A Man and His Museums

We met with the mountaineering legend in the Dolomites, where the late architecture icon Dame Zaha Hadid designed the last of Messner’s six mountain museums: MMM Corones. Emerging surrealistically from the earth at the top of a mountain called Corones in northern Italy are huge concrete tubes. One writer described them as resembling “a spaceship that has crashed into the peak and fused with the rock.” They are, in fact, apertures from a literally and curatively groundbreaking subterranean structure. They are the most unique features of MMM Corones, the last of six Messner Mountain Museums and the latest chapter in the extraordinary life of seventy-two-year-old Reinhold Messner, widely acknowledged as the greatest mountaineer ever.

The Italian mountaineer with the German name continues, in today’s parlance, “to give back.” His sixty or so books, films, lectures, and five-year tenure as a Green Party member of the European Parliament assure his legacy. And then, there are his museums—six of them, each with a different theme—located in northeastern Italy. Collectively known as the Messner Mountain Museums, they acknowledge and celebrate the world’s mountains and honor human relationships with them. Some have been built within the walls of ancient buildings, while others are brand new and no less than revolutionary.

The newest sits atop Corones (Kronplatz in German), which ranks as one of the Dolomites’ largest year-round recreational playgrounds. Skiers throng to it in winter, and hikers, mountain bikers, and parasailers have been dis- covering it in summer. Now MMM Corones also makes it a secular pilgrimage place for those who also revere mountains and the humans who live among them—and for the legions who worship Reinhold Messner.

Perhaps Messner became aware of Hadid’s talents from the large ski jump up the road in Innsbruck, which she designed in 1999 and which is used for the FIS Ski Jumping World Cup. Hadid later received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004. For Messner, she designed MMM Corones, which opened in July 2015. Just two months later, the Royal Institute of British Architects announced her as the first female recipient of the Royal Gold Medal—instituted in 1848—for lifetime achievement. Sadly, only eight months after MMM Corones opened its doors, the museum's esteemed architect died suddenly. Hadid had contracted bronchitis in March of 2016 and suffered a heart attack while being treated in the hospital.

"The theme is rock—original, traditional mountain climbing is to rise again."

His concept was very specific: “In the first tunnel, a window looking out southwest to the peak of the Peitlerkofel mountain, in the second, another window should look south toward the Heiligkreuzkofel peak, and in the third, a balcony should face west to the Ortler and South Tyrol.”

Hadid took those concepts and ran with them. Above the entrance to the three-level museum is a sharp glass canopy that evokes a fragment of glacial ice. Inside, ramps and staircases recalling mountain streams and waterfalls link concrete galleries in a flowing, organic fashion that feels like a smooth cave. The windows frame the mountains, providing constrained, controlled views. The best one opens exuberantly to a terrace cantilevered over the valley far below; the view is panoramic, simply stunning.

Hadid said of the structure, “The idea is that visitors can descend within the mountain to explore its caverns and grottos before emerging through the mountain wall on the other side, out onto the terrace overhanging the valley far below with spectacular, panoramic views.”

The museum is also environmentally correct. Being mostly underground, it maintains a consistent year- round temperature. An impressive 140,000 cubic feet (3,964 cubic meters) of earth was excavated and moved during the construction process, but once the building was nished, covered, and revegetated, its footprint became modest. Its design emotionally and visually links the mountains outside and the exhibits inside, which honor the tools and techniques of traditional mountaineering that are Reinhold Messner’s roots.

Messner’s Extraordinary Mountaineering Feats

None of this modern repository to the mountain heritage would exist without Messner’s unmatched feats in the high, wild, and remote parts of the world. He was the first to climb all fourteen of the world’s 8,000- meter (26,247-feet) peaks, which are known as “eight-thousanders.” He was determined to complete all of these mountains, and achieved some only on the third or fourth attempt. He also was the second to climb the legendary “seven summits” (the highest peaks on all seven continents) and the first to do so without supplemental oxygen, including Mount Everest. In fact, he stood on the top of the world’s highest mountain twice, first with his Austrian climbing partner, Peter Habeler, from the Nepalese side, and once soloing from the Tibetan side—during the monsoon season.

Messner’s first major Himalayan climb was back in 1970. He and Günther were part of an expedition to the previously unclimbed Rupal Face of Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat. Terrible weather forced them to make an emergency bivouac at the summit—no tent, no sleeping bags, no stove. In the morning, they started down in a storm via the Diamir Face, a different route. It was to be a tragic day. Reinhold lost six toes to frostbite. He also lost his brother to an avalanche. He returned to the mountain to search, unsuccessfully, for Günther’s body, which did not emerge from its icy tomb until a heat wave in 2005. That awful experience thirty-five years earlier and the harsh judgments of the mountaineering community would have been more than enough to deter a less intense man from other expeditions. But he continued exploring, achieving, and learning.

In Messner’s youth, expedition climbing pioneered by the British was the norm. He soon became convinced that such massive expeditions were not only counterproductive to the chance of success in conquering high peaks but were in his view, cheating, because guides and porters did all the hard work. He was a pioneer in what has come to be called “alpine-style climbing,” carrying everything he needed on his back and moving as quickly as possible. These climbs, either solo or done with just one or two partners, not only led to success but were less impactful on the mountains.

Over the years, Messner became increasingly captivated by mountain cultures with people’s beliefs expressed in art, spirituality, and convictions. He brought back artifacts and photographs from his expeditions to distant mountain ranges in exotic places. After a time, he turned his attention from the vertical world of mountains to the more horizontal realm of epic treks across wild, largely empty land. Long overland slogs—across the Greenland ice sheet, across Antarctica via the South Pole, and across Tibet—without snowmobiles or other machines and only the most minimal communications equipment. The miles and the vastness left time for contemplation and sometimes hallucinatory visions of what was, what might be, and what could be when he returned home.

The Tale of the Hammer

One memory that remained etched in Messner’s mind for decades involved a single climbing implement, a hammer. While still in his twenties, he wrote an essay about rock climbing whose title translates to “Murder of the Impossible,” in which he lambasted the increasing use of bolts and assorted gadgets to meet and overcome climbers’ greatest challenges. “Faith in equipment has replaced faith in oneself,” he wrote at the time.

After it was published, Messner received a letter written in a spidery hand from a then ninety-six-year-old Austrian lady. Messner recalls, “She said, ‘Reading your article, I was reminded of my boyfriend, my big love, Pauli.’ ” Pauli was Paul Preuss, an early advocate of reliance on skills and courage and not a lot of gear, as Messner would proclaim decades later. Preuss did have a hammer but, as the story goes, was opposed to pounding pitons into rock if it could be avoided. “He had two pitons in his life,” Messner told a reporter years later. “One I have, and the other is in a rock wall that I know.” Preuss was committed to such a purist approach despite its greater risks. In 1913, when he was twenty-seven, Preuss fell to his death while free-soloing the North Ridge of the Mandlkogel, a peak in Upper Austria.

He was one of Reinhold Messner’s climbing heroes. Messner was honored when the lady sent Preuss’s hammer to him because his philosophy and climbing style echoed her beloved’s. She stipulated that after Messner’s death, the precious object had to either be passed on to another like-minded climber or be put on display. Messner recalled, “I had that hammer in my cellar, and always when I saw it, I was thinking, ‘Oh, I have to begin a museum.’ Around this hammer the whole museum idea began to grow.” And that is how the Messner Mountain Museums came to be. The hammer that started it all is appropriately on display at MMM Corones.

"I had that hammer in my cellar, and always when I saw it, I was thinking, ‘Oh, I have to begin a museum.’ Around this hammer the whole museum idea began to grow."

But before Corones came five other museums. MMM Juval was the first, opening in 1995 in Juval Castle near the town of Vinschgau. Its theme is mountain myths, and in addition to proving that a mountaineer could conceive, open, and curate a museum, it serves as the Messner family’s summer residence.

MMM Dolomites, housed in a World War I fort on Monte Rite near the town of Cortina d’Ampezzo, opened in 2002. Its theme is the “vertical world” of the Dolomites, covering the opening up of this once-remote range and its history in peacetime and in war. During World War I, this was the region where mountain warfare was first conducted. Both sides’ dreadful losses came more from severe cold, rockfalls, and avalanches than combat.

MMM Ortles’s theme is the realm of snow, glaciers, and the world of ice in general, and expeditions to the poles in particular, environments that Messner has experienced intimately. Built into the mountain on a hillside near Sulden, it opened in 2004 and features art and artifacts to depict the power of avalanches and other forces of nature. When asked about global warming and climate change, Messner’s Green Party side rues what is happening to the planet these days, but his alpinist side comes out when he says, “We feel global warming in the mountains, but heat is not a problem for climbers. Cold is more of a problem.”

MMM Firmian in Sigmundskron Castle near Bolzano houses the museum’s headquarters, event space, rotating exhibitions, and a 200-seat theater. Devoted to the history and art of mountaineering, it is a modern museum built within the ruins of a fifteenth-century castle. Messner spent five years negotiating and planning Firmian, which opened in 2006. Architect Werner Tscholl, a specialist in castle conservation, created exhibition space without destroying the original. The challenge was to preserve the historical walls of the castle in such a way that the new construction can be reversed if ever required or desired. The new parts are a background for sculptures, photos, symbolic objects, and mementos that Messner collected on numerous expeditions, as well as an annual special exhibition.

MMM Ripa at Bruneck Castle, which dates from 1250, is the most intense cultural expression of Messner’s experiences. It opened in 2011 as the fifth Messner Mountain Museum. Dedicated to the mountain peoples from Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe, it focuses on cultures, religions, and even tourism. This interactive museum provides a forum for various mountain peoples to exchange experiences with the vibrant local farming community.

Reinhold Messner has spent his life seeking what he admits have been “the most difficult challenges,” not the least of them being the creation of the Messner Mountain Museums. He calls them “my fifteenth eight-thousander,” with MMM Corones the crowning achievement. His daughter Magdalena is now running the museums. But he is far from finished creating, exploring, and honoring.

In September, he set off for Africa to produce a film about a harrowing 1970 expedition to Mount Kenya. Drs. Oswald Oelz and Gert Judmaier from Innsbruck attempted to climb Africa’s second-highest mountain when disaster struck. A sudden rockfall swept Judmaier and a huge boulder down the mountain. It was a miracle that he survived at all. Grievously injured, he clung to life for nine excruciatingly painful days. Oelz ministered to him as best he could under dire conditions and with few supplies. Finally, an elite mountain rescue team flew to Nairobi, rushed to Mount Kenya, and managed to get the party off the mountain while Judmaier was still alive. It is a story that only Reinhold Messner could understand and film. He might consider its completion to be his sixteenth eight-thousander.