Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

How American Modernism Came to the Mountains

A daughter of America's midcentury-modern movement remembers how Chicago’s design elite settled in Aspen, giving rise to modernism in the mountains of the West.

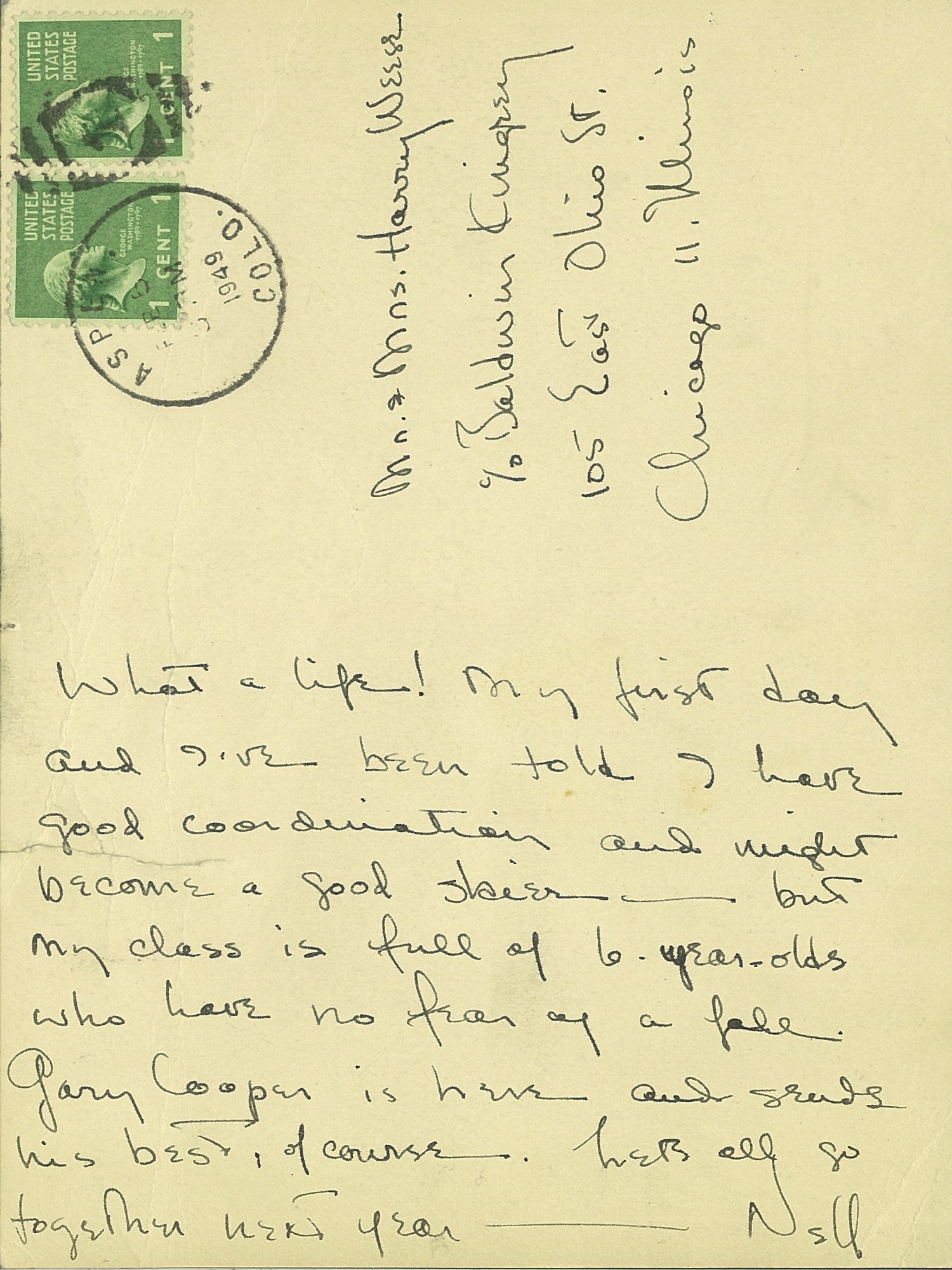

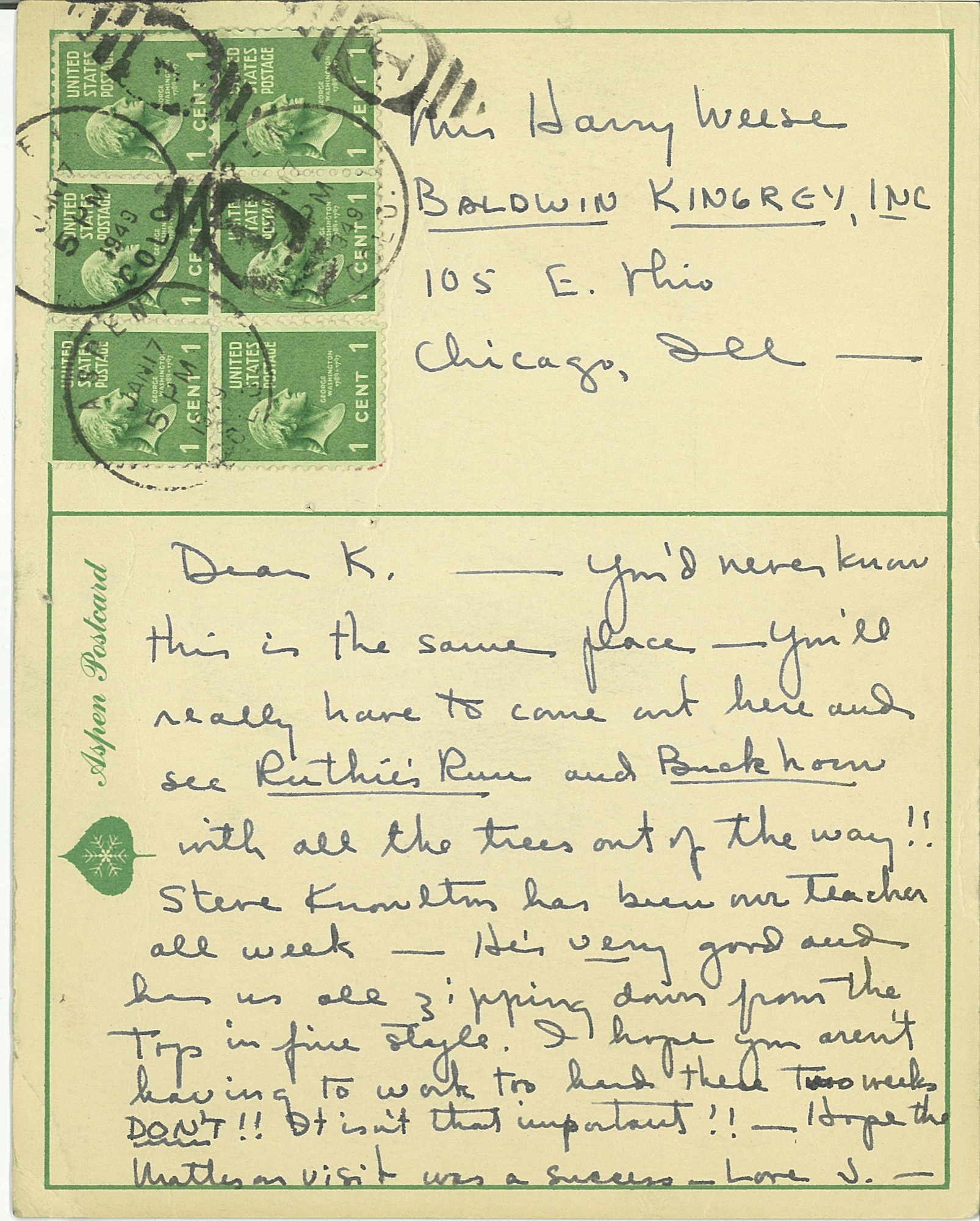

After World War II, Chicago’s design elite flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, galvanizing the then-sleepy alpine village with modern mountain chalets and avant-garde public buildings that helped transform Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley into the glamorous destination it is today. A memoir by artist Marcia Weese, daughter of Harry Weese, a central figure in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern.

Someone recently remarked to me that I was “born to design.” Over the years, I have come to appreciate this birthright, as I realize I have tenaciously and (mostly) joyously cleaved to the creative life, and still do. I have my parents, Harry Mohr Weese and Kitty Baldwin Weese, to thank for this. The creative life is not for the faint of heart, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Childhood in Chicago

It was the early 1950s in Chicago. As my mother told it,

“The war was over. No one had any money. No one had any furniture. Apartments to rent were scarce. We made do.”

When I was very young, we lived in a dim railroad flat in downtown Chicago. This was a typical inner-city apartment with a linear floor plan. The only natural light filtered through windows in the front and back. Chicago was a coal-burning city, and you could write your name on the window sills in the soot. I remember running down the dark hall that connected front to back, with crayon in hand. My parents encouraged my sisters and me to draw on the walls in that nondescript hall. What a great idea they had to spruce up the crepuscular gloom of the hallway, and how fun it was for us to break the rules.

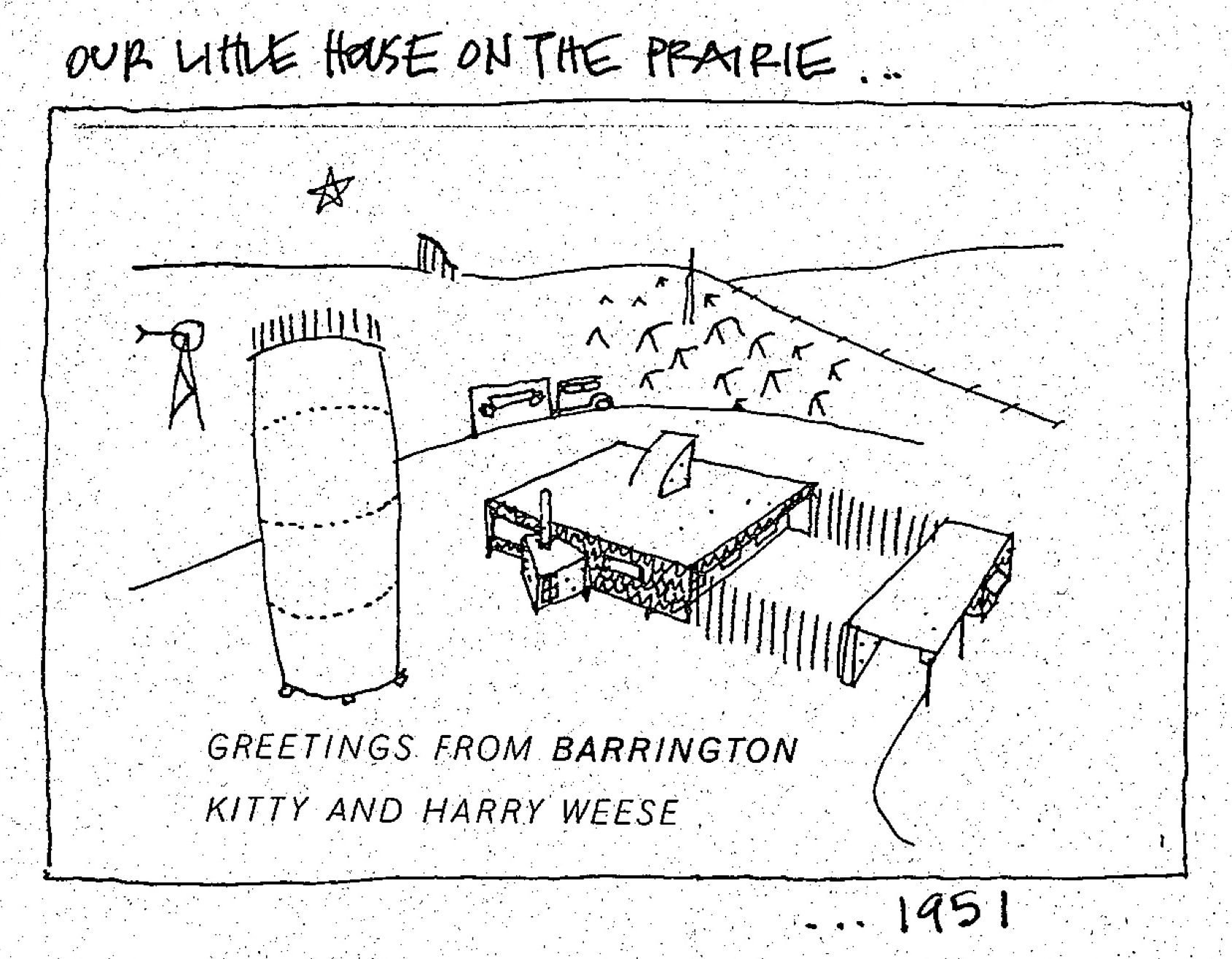

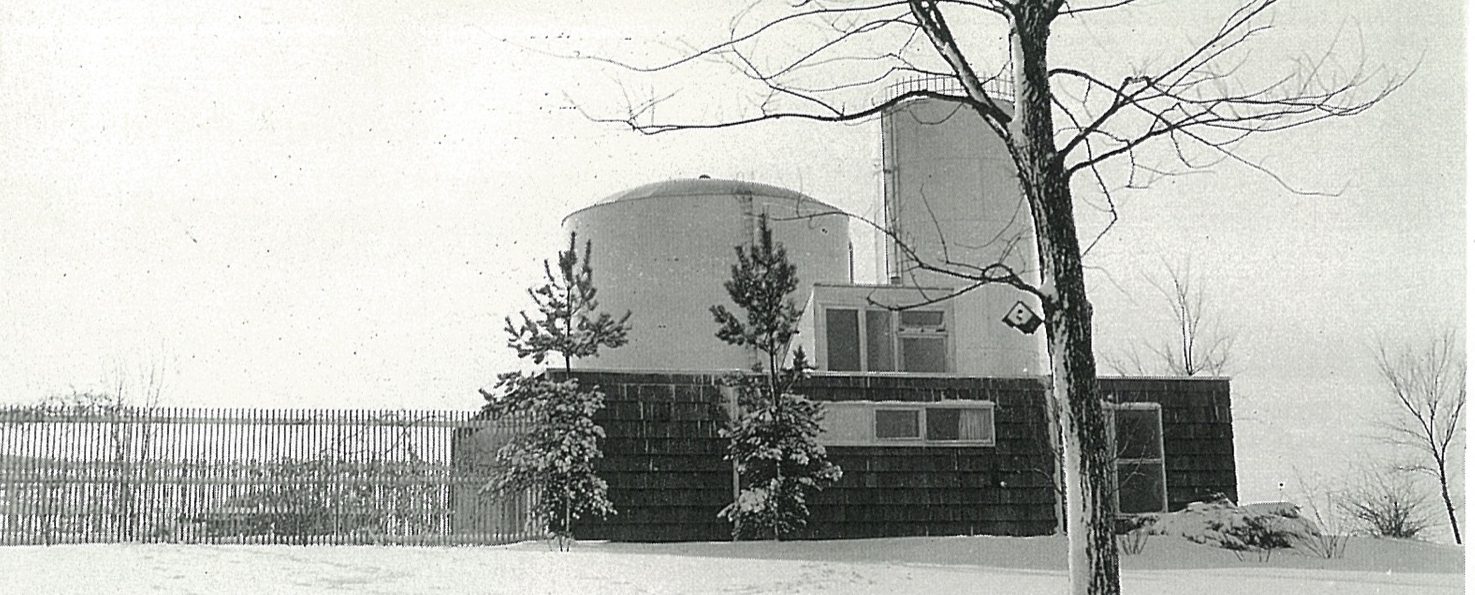

We spent weekends and summers in the country forty miles northeast of Chicago. Now it is wall-to-wall suburbia, but back then, we bundled our five-person family, one cat, two turtles, and several guinea pigs into the car and drove (pre-Kennedy expressway) through many stoplights to the little town of Barrington, Illinois. There, we lived in one of my architect father’s early houses. Built on a lot adjacent to two immense water towers belonging to the town, the house was modern and modest; a one-story house with a flat roof, carport, gravel driveway and a fenced-in garden the three bedrooms emptied into. It was sparsely furnished, and I will always remember the black-and-white linoleum floor. Mom found some dinner-plate-sized checkers pieces and we played checkers on that floor to our endless delight.

Some years later, my grandfather gave my father a nearby five-acre (two-hectare) plot of land, which consisted of a hill, many large oak and hickory trees, poison ivy everywhere, and a hand-dug lake topped off with a pet alligator. Here, my father built a wonderful and quirky house (prebuilding code) he named “The Studio.” We spent many years toggling between city and country. This was a refuge from the city for my parents, and for me, a secret garden of woodland flora and fauna.

Studying with the Eamses & Co.

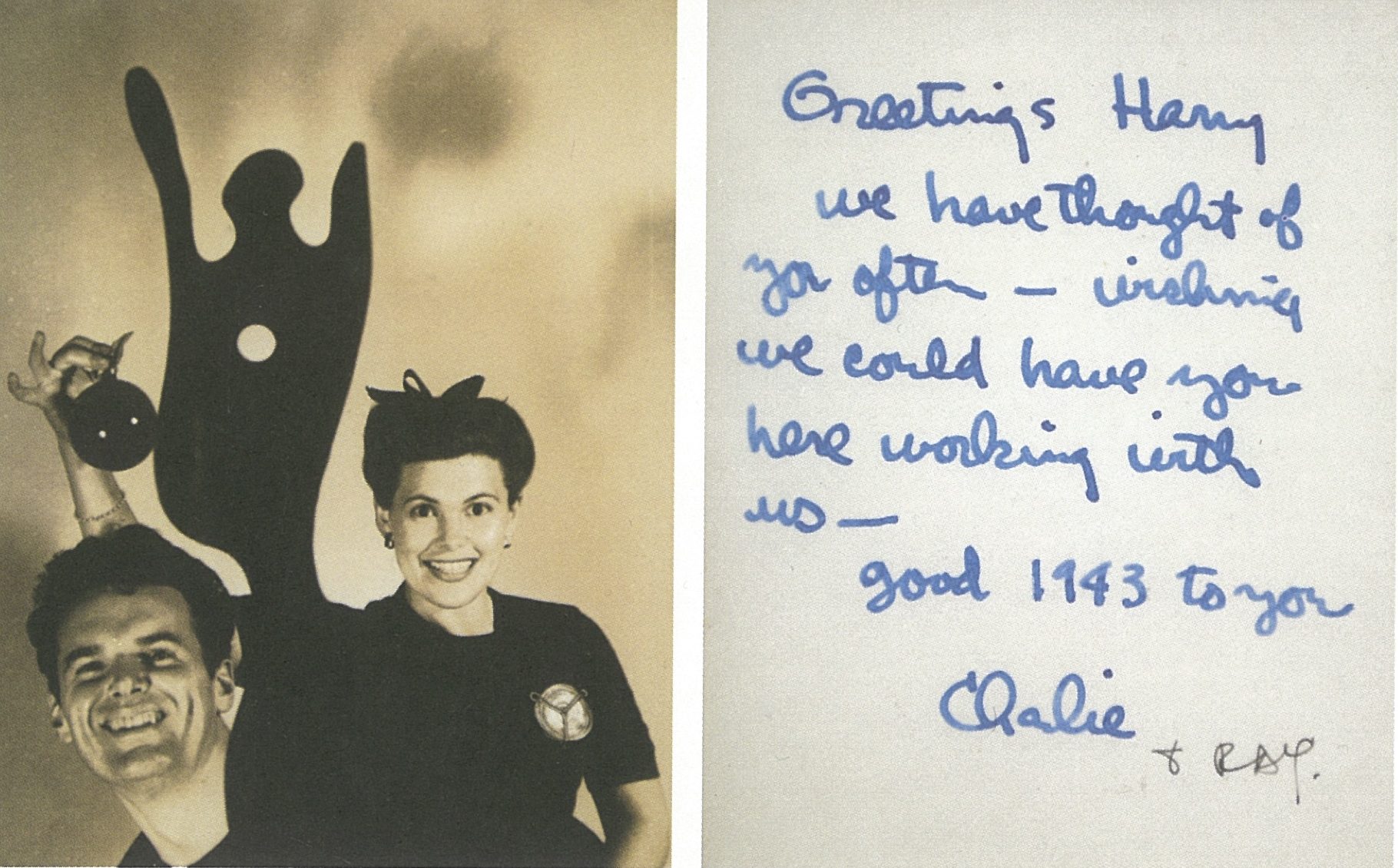

After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in architecture and engineering, Dad studied in Michigan at the Cranbrook Academy of Art with Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ben Baldwin, and a host of others who were living and creating modern design at a time when the atmosphere was ripe for it.

As history has revealed, many became household names, even demigods, in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern. These people were some of my parents’ closest friends.

My father and Ben Baldwin had won a few industrial design awards from the Museum of Modern Art while at Cranbrook, so they decided after graduation to “hang a shingle”—Baldwin Weese—to practice architecture in New York City. They worked together for a year but decided to convivially go their separate ways; Ben stayed in New York, and Dad returned to his birthplace, Chicago. But first, Ben introduced my father to his sister Kitty.

When Harry met Kitty

As my father approached the house to meet Kitty for the first time, she watched him jump over the fence rather than use the gate. That did it for her. He was a nonconformist, an inventor, a man who loved to use the path less traveled. He had no use for convention as it was, in the post WWII era. The overriding spirit was “rebuild,” therefore “build anew.” This was the perfect time for him to launch his architectural career in Chicago. He founded the architecture firm Harry Weese & Associates, which lasted for fifty illustrious years. My mother, who was southern, elegant, and graceful, was over the moon for this artistic, restless spirit. Not a typical match, but it worked; he needed her organized calm and “good eye for design” to manage his ambitions.

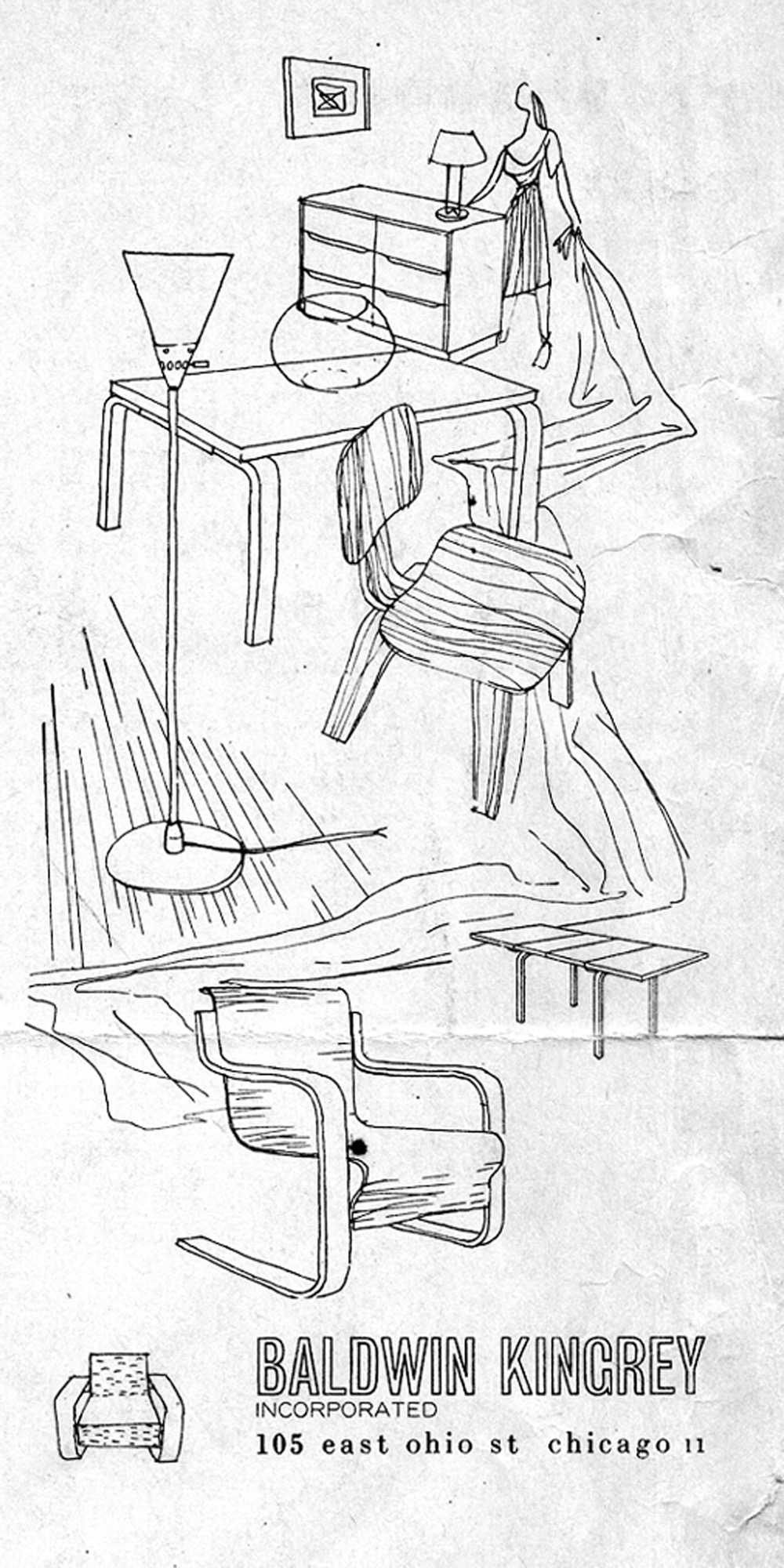

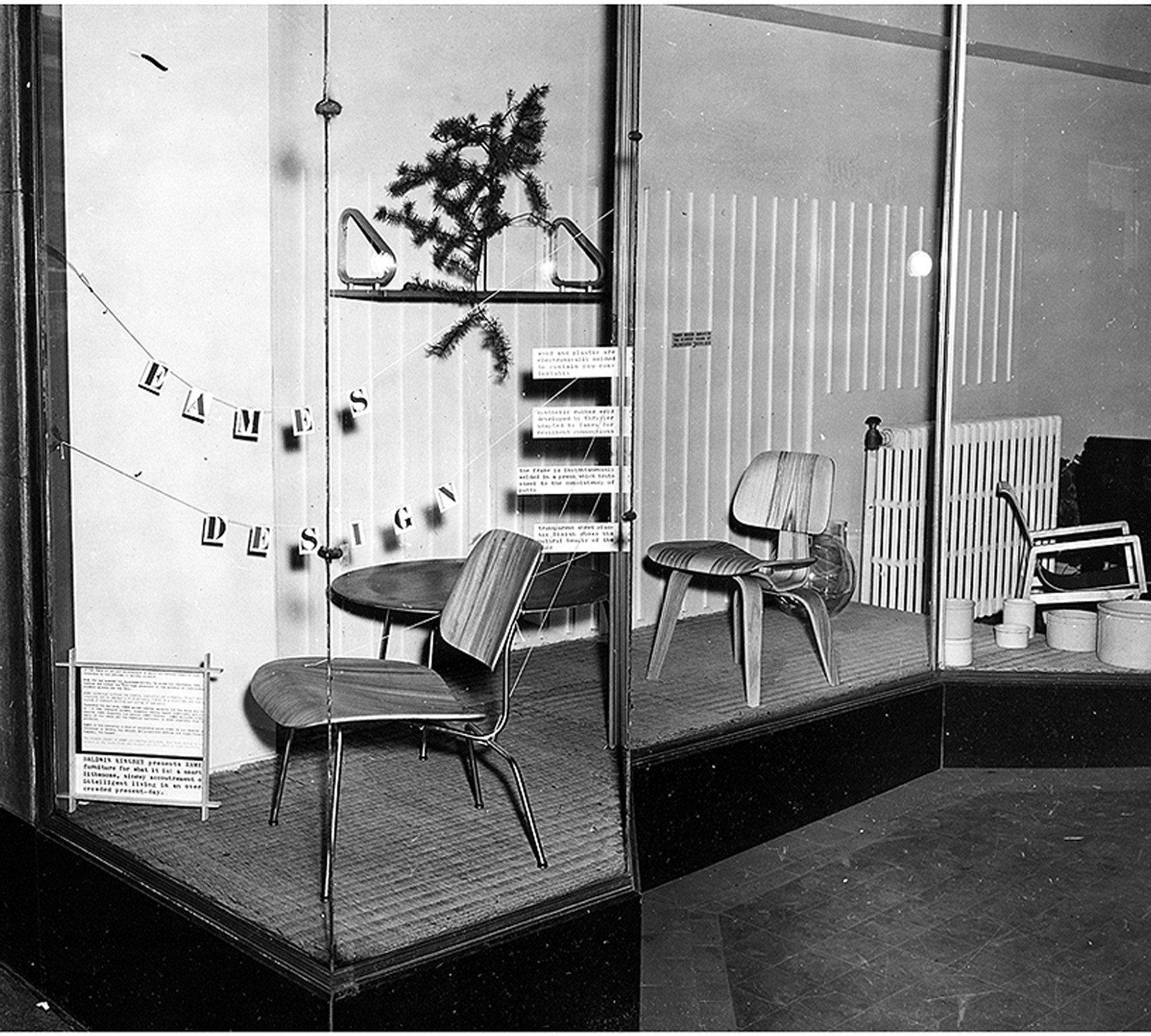

Baldwin Kingrey store in Chicago

In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father. While in the navy for three long years he kept a journal that he scratched in during calmer moments at sea. Here is an excerpt describing his vision for a retail store, entered on May 26, 1943,

“Thought of the (retail furnishings salon) shop for gathering together all beautiful and useful modern objects, which could be termed ‘furnishings’... Anonymous discoveries and subcontracted and assembled pieces of my design: foam and webbed couch in church pew form, telescoping coffee tables of magnesium or plastic, ... fabrics ... grass matting to a special design ... restaurant adjacent, movies, bar, a small haven for those interested ... a trip abroad to buy imports first thing after peace.” “In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father.”

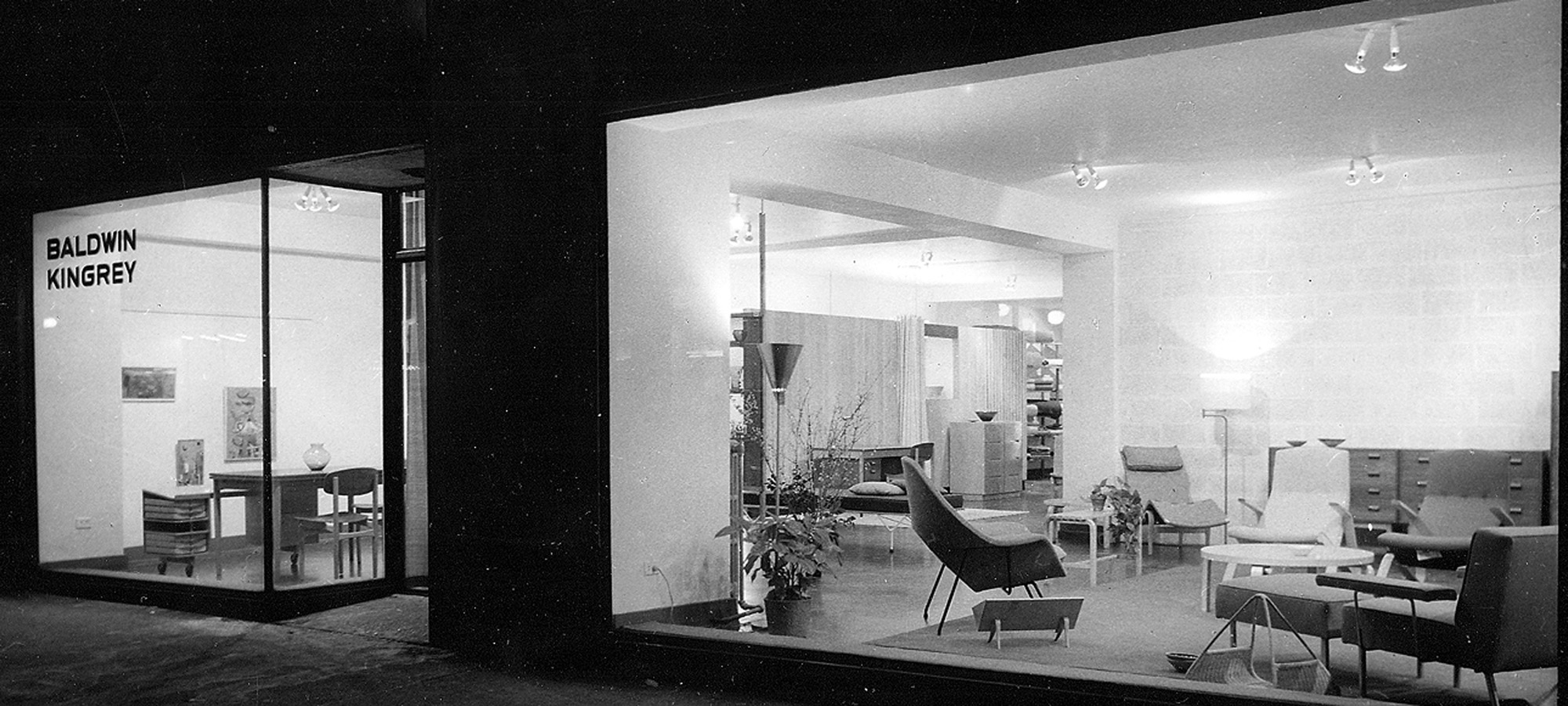

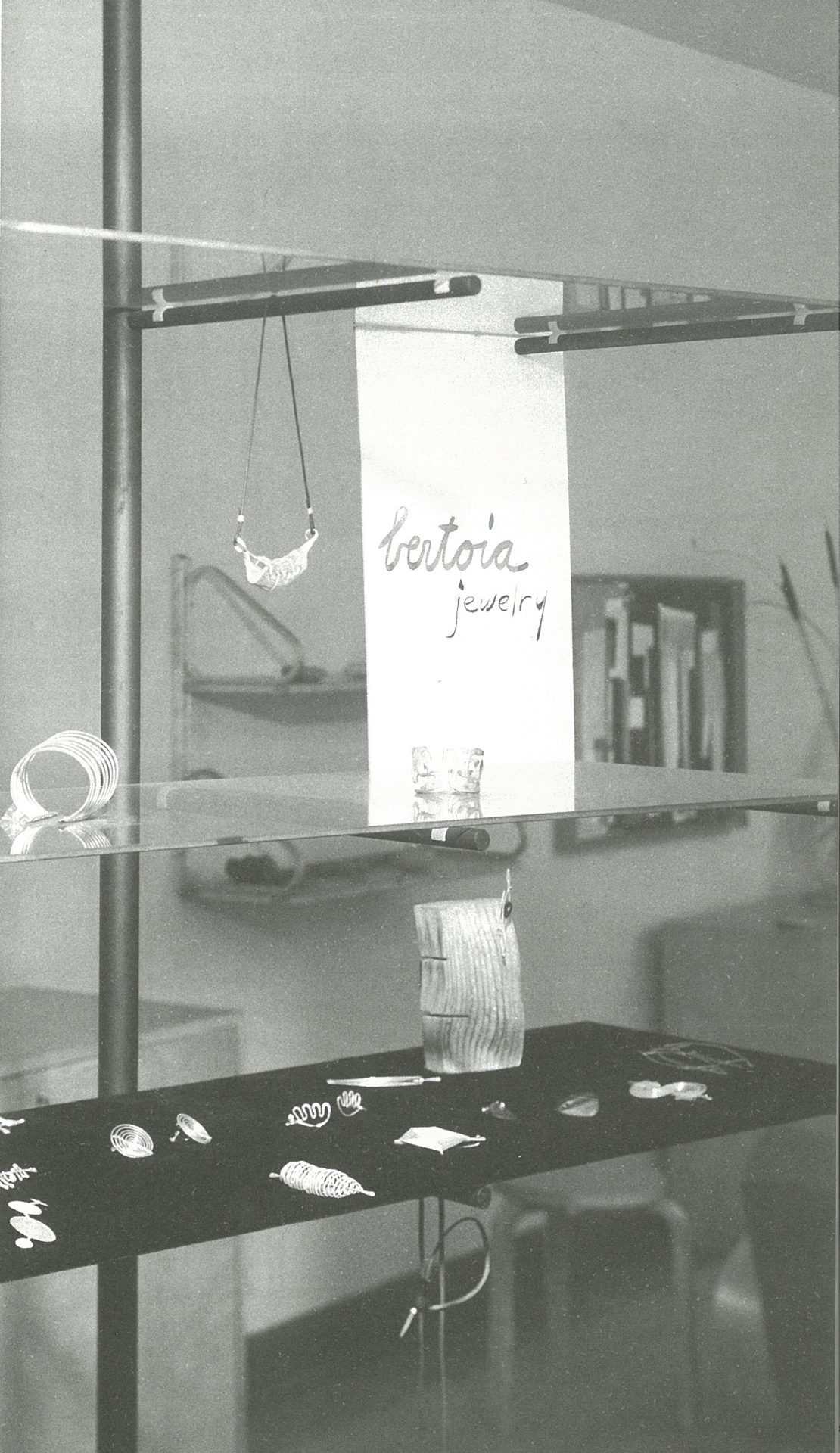

Wasting no time postwar, Dad got permission to handle the Midwestern franchise for Artek furniture from Scandinavia. Ben Baldwin designed fabrics and window displays. Harry Bertoia showed his jewelry, James Prestini sold his turned wooden bowls, artists queued up to exhibit in the space, and Baldwin Kingrey opened its doors to an eager audience hungry for modern design.

In words from John Brunetti, author of Baldwin Kingrey, Midcentury Modern in Chicago, 1947–1957,

“Baldwin Kingrey was more than a retail enterprise. It served as an informal gathering place for students and faculty from Chicago’s influential Institute of Design (ID) as well as the city’s architects and interior designers, who looked for inspiration from the store’s inventory of furniture by leading modernist designers such as Alvar Aalto, Bruno Mathsson, Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen.”

My father started his architectural practice at a drafting table in the back of the Baldwin Kingrey store. He did all the graphics for the store, designed a line of furniture and lighting he called BALDRY, designed open shelving of floating glass and steel poles to display Bertoia jewelry, Venini vases and “Chem Ware”—beakers and Petri dishes in simple, beautiful forms, that they found in the industrial section of the city. There was resourcefulness, an informality, and a frugality at play. In my mother’s words,

“Harry and I stopped at a place that sold Cadillacs on LaSalle Street. They were selling out their leather for automobiles, so we bought the whole batch. A lot of our furniture was covered in Cadillac leather! We were in a sense the precursor to Crate and Barrel. They came down to study us a lot. Carole Segal (founder of Crate and Barrel) was a friend of mine, and I gave her help. I gave her a lot of source material.”

As I was growing up, there was a steady stream of visitors, all immersed in modern design. My mother reminisced,

“You couldn’t travel across the country without changing planes or trains in Chicago. Everyone would stop in Chicago. The people that rushed into Baldwin Kingrey were mostly from the city and they didn’t have much money. Instead, they had some sort of new outlook—a vision. They loved the simplicity of our ‘plain’ furniture.”

The road was unpaved, the waters uncharted, the possibilities endless. Many would visit our house to exchange ideas, talk about projects, drink a cocktail or two, even draw at the dinner table. One of these more salient meetings I remember clearly:

I must have been ten or eleven when a distinguished elderly gentleman came to visit us in Barrington. My father was notably excited to share our modern house with him. When it was time to leave, he escorted him down the walkway under the grape arbor to his car with me trailing behind. As he drove off, my father turned to me with tears streaming and whispered, “There goes my mentor. There goes the most important man in my life.” This was none other than Alvar Aalto, who had been Dad’s professor and was a great influence on his architecture and design philosophy.

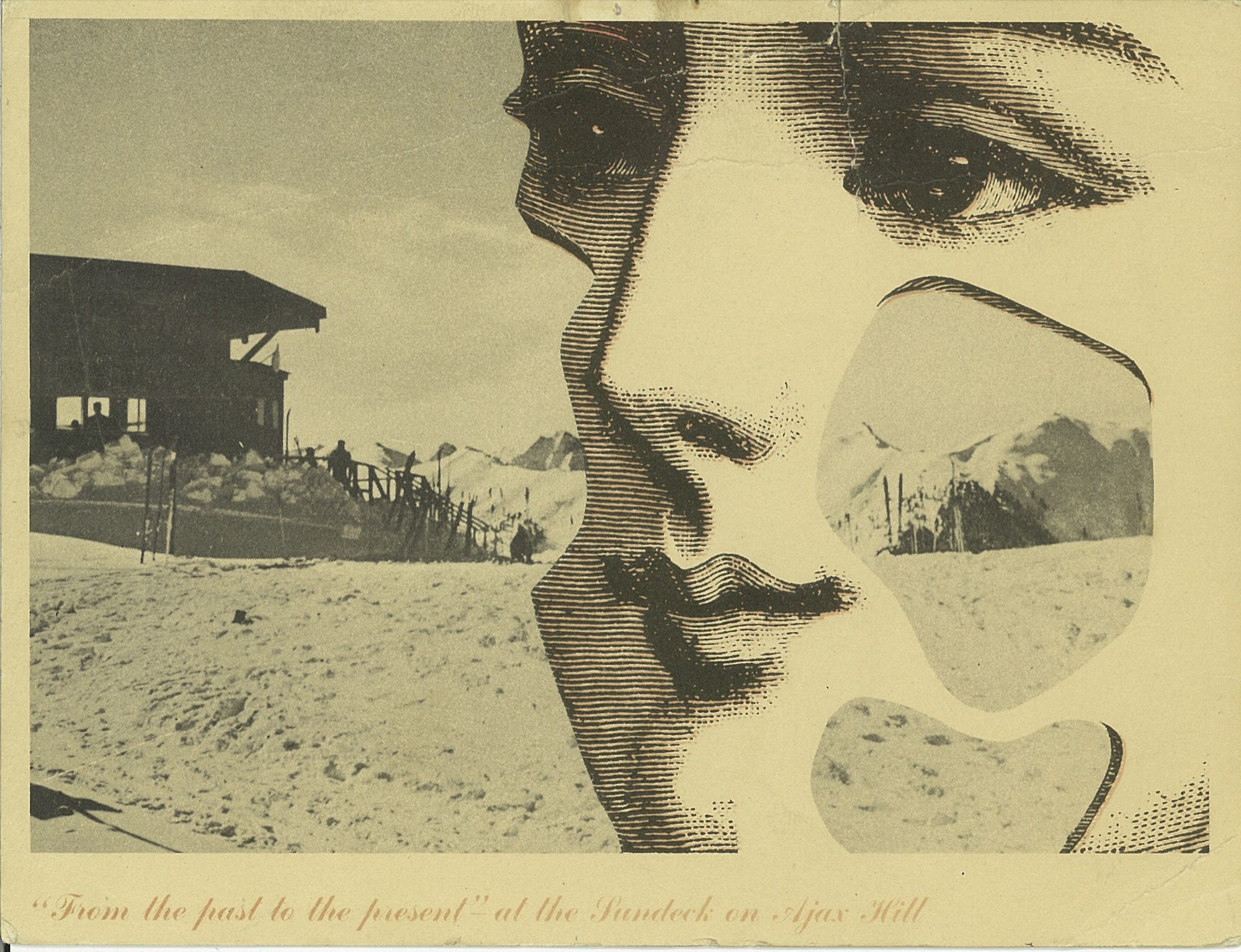

First pitstop in Aspen

When peace came in 1945, Dad stepped off his ship in San Francisco and he and Mom drove eastward. On their way back to Chicago, they stopped in Aspen and took some black-and-white photographs of downtown. The town consisted of several stone and brick buildings—the Courthouse, the Wheeler Opera House, the church and Hotel Jerome. All other structures were small Victorians, a few storefronts, dirt roads, and occasional wooden lean-tos that sheltered a few dozing horses. Many of the houses had been plunked on rubble walls to speed construction for miners and their families in the boom of the late 1800s. Builders often used pattern books with a 12/12 pitch for snow load, imparting a human scale that has long since been lost.

Dad—an avid skier—fell in love with Aspen and began a tradition of visiting each winter and summer that lasted throughout his life. Luckily, he included us in this adventure, and, thus, I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as “the town Chicago built.”

“I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as ‘the town Chicago built.’ ”

In the 1940s in Chicago, my parents were friends with Walter Paepcke, a successful industrialist, philanthropist, and president of the Container Corporation of America. It was Walter’s remarkable wife Elizabeth, a notable influence on Chicago’s cultural life and one of Mom’s favorite people, who exposed Walter to modern design and artistic sensibilities. In this spirit, Paepcke consulted with Walter Gropius, brought Laszlo Maholy-Nagy to the Institute of Design, befriended Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer, and photographer Ferenc (Franz) Berko, also at ID at the time. Mom and Dad intersected with ID, as the campus was a hub for young and ambitious modernists.

In a memoir, Elizabeth Paepcke describes her first impression of Aspen after skinning up the mountain in 1939,

“At the top, we halted in frozen admiration. In all that landscape of rock, snow and ice, there was neither print of animal nor track of man. We were alone as though the world had just been created and we its first inhabitants.”

Walter Paepcke first visited Aspen in the spring of 1945 urged by Elizabeth. To him, this seemed the idyllic place to implement a new Chautauqua. The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, “for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.” Thus the Aspen Institute of Humanistic Studies was born. Herbert Bayer was brought in to oversee the design of the campus, and Franz Berko became the Institute’s in-house photographer. The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.

“The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, ‘for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.’ ”

“The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.”

There was a palpable charm to Aspen in the fifties and sixties, which I feel so fortunate to have experienced first hand. Many Europeans returned to the town to settle after serving in the famed 10th Mountain Division during the war. Their training camp, Camp Hale, was nearby and enlisted men would often ski Aspen on the weekends. Friedl Pfeifer was one who started the Aspen Ski School; Fritz Benedict set up an architectural practice. After the war, many of these veterans taught skiing in winter and worked as carpenters in summer. Their wives typically ran the shops, bakeries, and clothing stores in town. Franz Berko stayed, continued his photographic career, and raised his family. His wife Mirte ran a toy shop that sold wooden toys from Europe. Herbert Bayer designed the early buildings at the Aspen Institute and settled in town with his wife Joella. Fritz Benedict, the noted local architect, married Joella’s sister Fabi, and he began developing Aspen. Joella and Fabi shared a famous mother—the poet Mina Loy. This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its “quiet years.” My parents were in the midst of the action.

“This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its ‘quiet years.’ ”

Christmases at the Hotel Jerome

Nora Berko, daughter of Franz and Mirte, remembers visiting us at the Hotel Jerome every Christmas. We always stayed in the southeast corner with full view through the Victorian lace curtains of Main Street and Ajax Mountain. As our collective parents went out to dinner and dancing, usually at the Red Onion, we had full run of the rickety hotel, much like Eloise at the Plaza. With its worn and dusty velvet furniture, Victorian floral wallpaper, and black-and-white photos of skiers sporting the reverse shoulder stance and the latest style of stretch pants, it was a far cry from our modern and minimal environment at home. We ran up and down the creaking stairs and played in the elevator—a novelty—as it was the only one in town. The rooms cost ten dollars per night, radiators clanked, and in some seasons ropes were ceremoniously draped across the room sinks warning of giardia in the water. But we loved the Jerome. It felt like an old comfortable shoe. The Paepckes leased the hotel as well as the Opera House so Elizabeth had license to paint the exterior white with light blue arches over the windows. The hotel looked like a grand Bavarian wedding cake in a perpetual wink; an impressive structure always easy to spot for a youngster finding her way home after ski school. It stayed this way for several decades.

Every Christmas we walked through snowy streets to the Berko’s for Christmas dinner. Their house was a modestly scaled and cozy Victorian in Aspen’s west end. Real candles burned on the Christmas tree, which was festooned with wooden ornaments from Mirte’s toy shop. Marzipan treats imported from Europe were served. There was no central heat. Brrrr. But for a young girl, I was sure that I was encompassed within a magical snow globe.

Aspen became our second home

In the late sixties, my mother bought a small Victorian in Aspen's west end for a mere pittance. We began to spend summers in the mountains, which was a blessed relief from the mugginess of the Midwest. My father worked on projects in and around Aspen. Many went unbuilt but some were realized, including the Given Institute. He had a plan for a new airport, and he wanted to bring light rail from Glenwood to Aspen to alleviate vehicular traffic. Always drawing, usually at the kitchen table, I rarely saw him without a pencil in hand. In 1969 Charles Moore (who taught at Yale), and Fritz Benedict lured a class of Yale architectural grad students to spend a summer in the nearby mountains and build experimental projects. When these young, handsome students appeared, they were eager to rub shoulders with my father at his kitchen table. (A few rubbed shoulders with his daughters as well!) One of these architects, Harry Teague, arrived and never left. Over four decades, he has made a significant imprint on the town, designing notable residences and many of Aspen’s most prestigious cultural buildings, including Harris Hall, the Aspen Music School campus, and the Aspen Center For Physics. He has become one of Aspen’s “own” by championing a humanist aesthetic that continues to raise the bar of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley.

Aspen today

Though old Aspen is rapidly fading, thank goodness there are offspring. I am currently collaborating with Teague on a family compound for Nora Berko and her family that incorporates her father’s studio, now designated historic. Her daughter Mirte has dedicated much time and effort organizing her grandfather’s impressive archives of photographs for us to appreciate into perpetuity. The Aspen Institute carries on robustly while continuing to pay homage to its early founders and players. △

Read "Growing Up Weese" to find out what artist and designer Marcia Weese is up to today.

Growing Up Weese

The daughter a power couple of American modernism, artist Marcia Weese was born to design

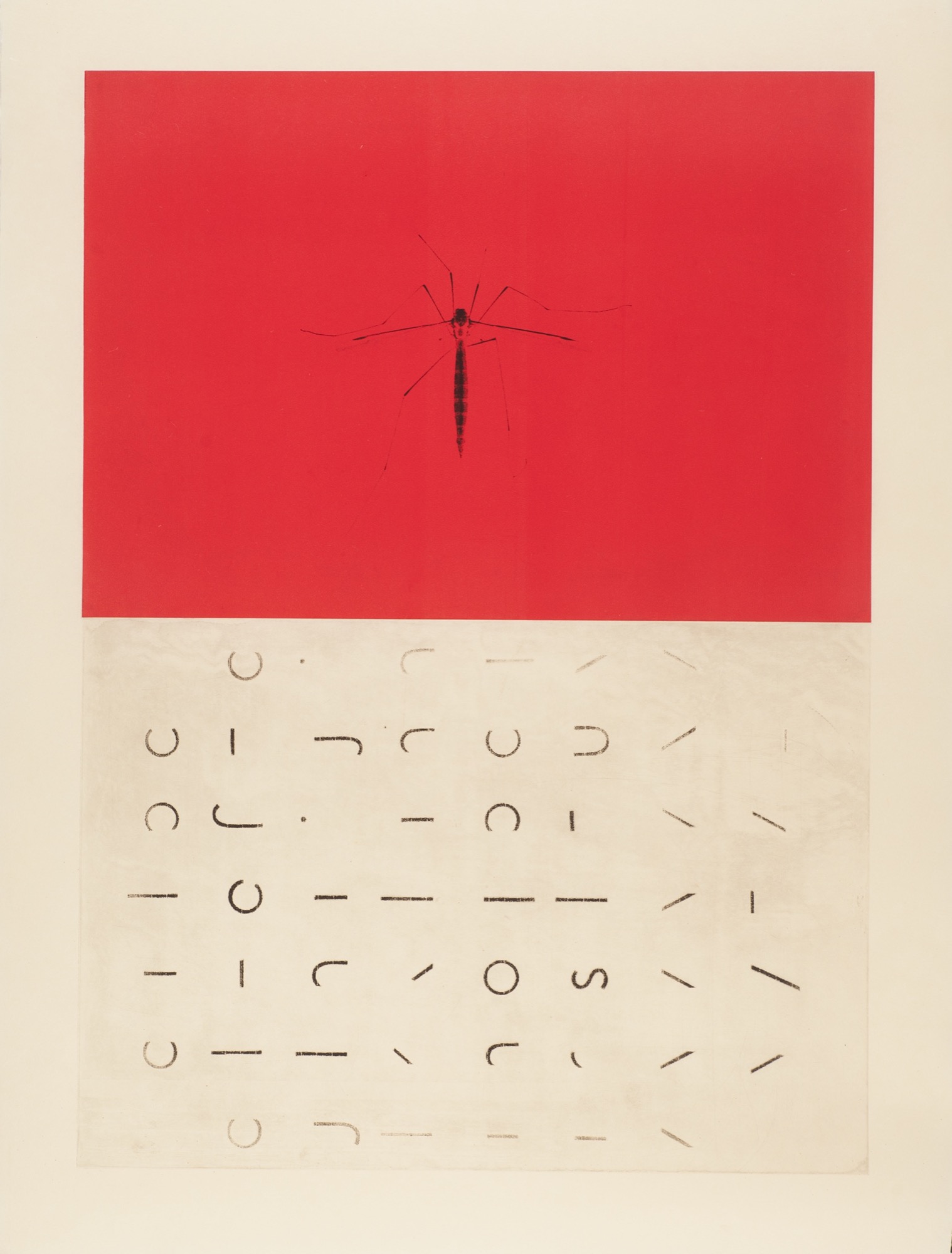

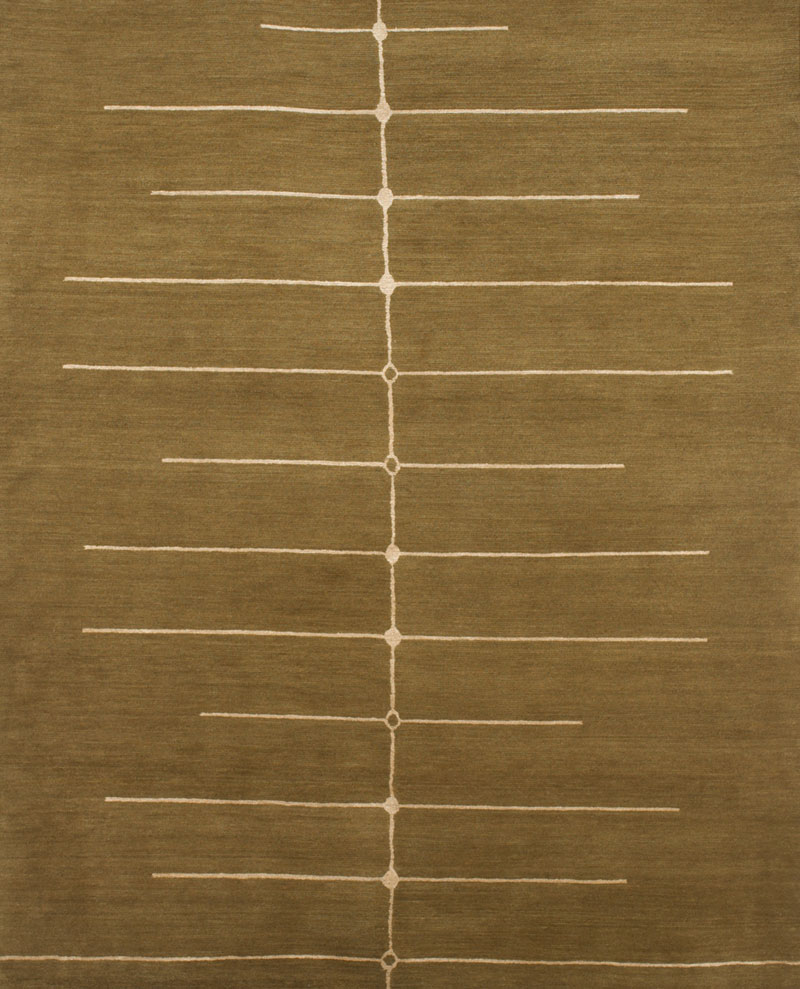

Her parents are architect Harry Weese and pioneering design shop founder Kitty Baldwin. Born into a coterie of mid-century modern architecture and design icons—Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, and Charles and Ray Eames among them—artist and interior designer Marcia Weese carries on family tradition by designing modern rugs and creating fine art prints in her studio in the Colorado mountains.

I grew up on the near north side of Chicago near the lake. The endless horizon line, burning coal, bus fumes, beach sand, roller skates, sirens, frozen waves, thunderstorms, pigeons, dandelions ... Life in the inner city was complemented by summers in the country forty miles west. Crickets, lighting bugs, oaks, jays, owls, leaves, slugs, snake grass, otters, bluegills, cabbage butterflies, algae, sumacs, worms, Queen Anne’s lace, garter snakes, rabbits, clover, flies, bullfrogs ... I was lucky to dwell in both worlds. And each winter we spent the Christmas holiday in Aspen, and I fell in love with the Rocky Mountains, too. Streams, Indian paintbrush, marmots, boulders, puffballs, eagles, gentians, boiled wool, marzipan, scree fields, cumulus clouds, ravens, purple snow shadows, ermine, the smell of wet dirt...

The natural world has always been an oasis for me—a sanctuary, a place in which to marvel and explore. I borrow imagery from natural forms, weather patterns, textures, to bring a sense of balance to my world. My content often comes from the mystery and magnificence of nature—the perfect designer.

“My content often comes from the mystery and magnificence of nature—the perfect designer.”

Trained as a sculptor, I was attracted to site-specific work that often incorporated architectural elements. Printmaking was a natural antithesis to the rigor of planning and making sculpture, and as I look back, I have devoted most of my artistic life to works on paper. The ephemeral quality and the spontaneity speak to me. I am enchanted by the casual impermanence of a work on paper. And I am attracted to the minimal aesthetic, where I feel most comfortable. Less is more in my world.

“I am enchanted by the casual impermanence of a work on paper.”

As children, we would get the nod from mother that our father was coming home and it was time to "clear the decks.” All toys would be scooped up and hidden away so he could walk into a clean and serene environment. To this day, clutter confuses me and divesting is actually something I enjoy.

I moved to New York after art school to become the famous artist that is expected of all Bennington graduates. That was a nine-year lesson in humility and how to survive amid intense turmoil and fierce competition. I learned how to discern the excellent from the mediocre in art and design. I danced, made sculpture, painted, and longed for the horizon line. I found myself walking down the streets in Manhattan looking up at the rooftops. There, the sky silhouetted another cityscape of water turrets, parapets, and fire escapes. After nine years in New York, “Manhattanism” (i.e., "New York is the only place to live”), had gotten a problematic stronghold on me, so I escaped and returned to Chicago where I could breathe again. I loved walking along the lakeshore with the density of the city to the west and open water to the east.

I continued making art but asked my mother to teach me the ins and outs of the interior design profession so I could more readily support myself. She taught me well, and I have worked collaboratively with architects and clients across the country over a number of decades. As an interior designer with a classical modern bent, I was always searching for the quintessential modern rug to harmonize the room. I only found beige, beige, and beige or super graphic patterns that looked like bad paintings. Serendipitously, I was introduced to a family of Tibetan sisters, who knew the rug trade and had cousins in the business in Asia. This was a happy union, and for the past fifteen years I have worked directly with Tibetans who weave rug collections to my design in Nepal. Recalling visuals of growing up on the edge of Lake Michigan and the Midwestern prairie, to hiking the crags of the Rocky Mountains, my designs stem directly from my intersections with the natural world. The patterns and color palettes present an assemblage of modern but timeless rugs.

“As an interior designer with a classical modern bent, I was always searching for the quintessential modern rug to harmonize the room.”

When I eventually grew tired of Chicago’s pink skies at night and ached to see the milky way, I moved west to the Rockies.

Decades have passed, and the early modernists are still in vogue. Thankfully, this is beyond fickle fashion, which warms my heart as I feel I am surrounded by old friends and family. These days, when I encounter “everyday simple,” I pause and give thanks to my parents for teaching me that less is more. And I appreciate the efforts that are being made by those who are committed to good design and who are carrying on that noble tradition.

And I am ever grateful to have been handed the baton of creativity. It is an ongoing quest, one that continues to nourish, atop the peaks and in the valleys. △

“Decades have passed, and the early modernists are still in vogue. Thankfully, this is beyond fickle fashion, which warms my heart as I feel I am surrounded by old friends and family.”

Read "How American Modernism Came to the Mountains"—a memoir by Marcia Weese as the daughter to a power couple of early American modernism. Together with fellow members of Chicago’s design elite, Harry Weese and his wife, Kitty Baldwin, flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, bringing modern design and architecture to the Mountain West with them.

Zen and the Art of Knife-Making

Using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, a blacksmith in the Japan Alps makes knives so delicate and dangerous they turn chopping into an artful act of passion.

A blacksmith in the mountains of Japan uses skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword- making to forge knives from a steel that is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art.

Cutting, slicing, mincing, dicing, boning, peeling: Over time, these mundane jobs have become, for me, the most satisfying tasks in the kitchen. Now, I experience knife-work as a meditation on all that will unfold after food leaves the chopping block. With each cut, I’m trying to shape ingredients to their ideal form, whether it’s a fine mince of onion designed to melt in a pan as a base for a sauce or fifty wedges of apple that need to keep succulence while retaining their shape in an autumn pie. The key to this repetitive-motion, Zenish state is a sublime knife: balanced in the hand, dangerous, delicate, an obedient lover and assassin.

I found my sublime knife after a lot of looking. It has a blade of Aogami Super carbon steel and was hand forged in a mountain town called Niimi, 150 kilometers (93 miles) northeast of Hiroshima, at the shop of a fifty-seven-year-old blacksmith named Shosui Takeda.

My Takeda

If you lay my Takeda 180-millimeter Super Sasanoha Gyutou chef’s knife beside my shiny stainless Shuns and Globals and Henckels, it looks weathered, almost preindustrial. The thin blade has a mottled black finish called kurouchi. The blade tapers sweetly to a gunmetal gray edge whose sharpness approaches that of a razor. You can see the resin used to affix the tang as it was slid into a hole in the Indian rosewood handle during construction. The handle is octagonal, to answer the shape of enfolding fingers and palm. Near the upper rear of the blade’s spine, roughly stamped into the metal, are Japanese characters, plus a heart and the Western letters AS. The characters mean “Niimi. Shosui. Aogami Super.” The heart is something Takeda-san’s blacksmith father started to put on his blades many years ago. Takeda-san says he has never been quite sure what the heart means.

Finding the perfect blade

I have not been to Niimi. I met my Takeda—and, later, two more of them—through Google’s search power and the matchmaking tastes of an American in Tokyo named Jeremy Watson. Watson is a thirty-nine-year-old American of UK and Hong Kong ancestry who moved to Tokyo after a period teaching English in Japan (where he met his wife) and a period learning about, and selling, Japanese knives in Manhattan. In 2012, he founded Chuboknives.com, selling products he found by scouting artisan blacksmiths around Japan. Initially, he hand-wrapped each order, inserting a thank-you note into slim boxes covered in Japa- nese stamps, and sent them on their way to Australia, Europe, and the UK, where chefs and foodies were beginning to notice his trade in rare beauty. Now his business is such that he has automated the shipping. But the boxes remain lovely and intricate, befitting jewelry, and to receive a Takeda in the mail feels like a gift, even if you’ve paid for it.

“We wanted to be a small family business that was connecting small-scale artisans to chefs and home cooks,” Watson says. Big Japanese knife-makers, like Shun and Global, were taking up more and more display space in stores like Williams-Sonoma (where once German companies like Henckels had ruled), but “I realized that the smaller artisans and blacksmiths were really underrepresented. Shibata, Takeda, or Tanaka—the craftsman that we’re currently working with—weren’t really out there.”

The absence of these knives from the major retailers can be explained by the minuscule production of operations such as Takeda Hamono, as the company is called.

Takeda's workshop

“There are three blacksmiths, including me, at the shop,” says Shosui Takeda (whose answers were translated for me by Watson). “We spend eight hours a day forging, twenty-five days a month. In total, we produce 250 knives a month. If we calculate the number of hours all of us work, essentially each person is producing about three knives per day.”

The quality of a handmade knife derives from the strange mutability of steel when it’s repeatedly heated and hammered to alter its molecular structure. The blacksmith, using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, is always chasing an ideal: a blade strong yet somewhat exible, thin but not brittle, able to take an edge and hold it for a long time. A molecular map of a knife would reveal a variety of attributes across its form, determined by cycles of quenching (to harden the steel) and tempering (to selectively soften it). The spine may be softer than the edge. The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it. Takeda has been using AS for twenty-five years, after discovering it in a steel-maker’s catalogue, and after realizing that customers would pay a premium for the uncanny thinness and edge retention that AS offers. “As far as what I’ve seen,” Watson says, “I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as he does.”

“As far as what I’ve seen, I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as [Shosui Takeda] does.”

"The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it."

Watch the YouTube videos of Japanese knife-makers at work: heating steel and iron to narrow temperature tolerances in coal-fired furnaces, then beating away at the metals—using both power hammers and tools wielded by hand—until they begin to fuse and morph like slow-motion Plasticine. The shape of the knife is judged by eye—as is the temperature of the hot steel, judged by the color of its glow in the fire. Heat, hammer, cool, and repeat. Sparks fly. The blades curl out of shape, then return to form under the blacksmith’s art. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding.

"I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding."

That said, Takeda’s approach benefits from modern insights. “I’ve learned a great deal by collaborating with the steel-makers. Through trial and error and using high-resolution microscope photography to see how the steel looks after it’s forged, I’ve been able to eliminate problems with the forging processes.” He quenches his blades in successive baths of hot oil, whose temperature is closely regulated, then sharpens the edge with wheels and stones of increasingly fine grit. His wife and two daughters fix the tangs in the handles at the end, and handle other shop duties.

Dangerous business

The work looks dangerous because it is: “When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves,” Takeda says, “we get burns on our hands and arms every day. This is just part of the job and no big deal.

“What’s more serious are the repetitive strain injuries to my back, shoulder, elbow, and knees. Eight years ago, I had back surgery, and earlier this year, I had surgery on my right knee. I’m currently doing monthly injections so I can keep working. My grip strength is also significantly weaker than it used to be.

“The most serious is the hearing and vision damage. I use earplugs, but I still have hearing damage. Also, constantly looking at the coal-burning oven while forging has damaged my sight.”

"When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves, we get burns on our hands and arms everyday. This is just part of the job and no big deal."

All that pain may explain the paradox of the knife market in Japan. The rise of the global food and chef culture has created unprecedented demand for fine knives, and Watson says artisan shops have more orders than they can fill. The Internet makes new connections between cooks and artisans possible. It would seem to be a perfect time to grow a blacksmith’s business.

“The American solution to this would be to hire more people and build a larger facility,” Watson notes, “but that’s not necessarily the mentality here. A blacksmith team consists of three or four people, and it takes years to train.” Nor are young Japanese lining up for the work. This does not surprise Takeda. He did not intend to be a blacksmith himself; he helped around his father’s shop for bowling money, and didn’t take up the work properly until he was twenty-eight. Were his father not in the trade, he would never have pursued it.

Takeda describes the paradox this way: The knife business is good, the forging business is not.

“During my father’s time,” Takeda says, “there were forty-seven blacksmiths in Niimi—most making agricultural implements [as Takeda’s shop still does]. Now, there are just a handful. The small knife-forging business is literally going extinct. There are very few blacksmiths left.”

Care and maintenance

In my knife drawer are Japanese stones that I use to keep my Takeda knives sharp. The stones, soaked in water, give up a creamy slurry as the carbon steel of the knife is drawn across it. When the knives are done, I use a special little stone to smooth the water stones for the next session. Sharpening is a calming ritual that with a little practice leads to a gleaming thin line of razor sharpness along the gray edge of the blade.

When the knives are sharp, and again after every use, I carefully dry them, because Aogami Super is extremely prone to oxidation. It rusts in minutes. The rust is removed with a light scrub, should I fail to completely dry the knife; this is another little ritual that I enjoy. Takeda is now making an AS line with stainless cladding, which he calls NAS, to prevent rust, but I shall stay old school on further orders as long as he continues to produce them. And there will be further orders, even though his knives run from $120 for a beautiful little paring knife called a “petty” to $380 for an absurdly long, wondrously light Kiritsuke slicing knife that is my favorite cooking tool in the world.

Takeda’s blades have a gentle fifty-fifty bevel, meaning that each side of the blade tapers equally to the cutting edge. This is easier to sharpen for an amateur than the single-side bevels common on many Japanese knives. Beveling and blade shape, like everything else to do with Japanese knives, are complex and relate to the food to be cut: vegetables versus meat versus fish. Some blades are designed for species of fish, others according to what the fish is going to be used for. Everything is about form: of the blade, of the food.

These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief. One gets a glimpse of it at a very good sushi bar, while a multicourse kaiseki meal in Kyoto is like a doctoral dissertation.

"These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief."

Wielding my Takedas, I know that I shall never have such skills. But I do have knives that allow me to meditate on the ideal every day. △

Recipe: Muscovy Duck Breast with Chanterelles, Pickled Radish, and Foie Gras Gastrique

A fine duck dish starring mushrooms and pickled garden gems preserved from summer

INGREDIENTS muscovy duck breasts: 2 breasts salt pepper grapeseed oil chanterelles: 113 g (4 oz) shallot: 1, diced butter: 28 g (2 T) thyme: 3 sprigs

GASTRIQUE

reserved apple liquid: 236 ml (1 cup) from Whiskey Preserved Apples recipe shallot: ½, diced bay leaf black peppercorns apple cider vinegar: 118 ml ( cup) rendered foie gras fat: 30 ml (2 T)

Duck Breast

Preheat oven to 180° C (350° F). Carefully score the skin with a sharp knife. Season tempered duck breast generously with salt and pepper. On medium-high heat, heat grapeseed oil until the oil is hot. Sear, skin-side down, until skin is nicely golden brown. Place pan (with the duck in it) in the oven until the duck breast reaches 54.4° C (130° F). Remove duck from the pan, let it temper for a few minutes before slicing. Finish sliced breast with sea salt and set aside.

Chanterelles

Carefully clean the mushrooms to remove excess dirt. Once clean, heat a pan, add a small amount of grapeseed oil, and add diced shallot. Once the shallot is translucent, add the mushrooms, season with salt and pepper, and cook for 3–5 minutes. Add a knob of butter and a few sprigs of thyme. Once butter is melted and mushrooms are coated, remove from pan and set aside.

Gastrique

Remove half of the liquid from the cooked apples (see recipe). Place in a saute pan with diced shallot, bay leaf, and black peppercorns. Reduce liquid by half, add apple cider vinegar. Reduce the liquid another quarter (total time 8‒10 minutes). Strain and return to cleaned sauté pan. Add a tablespoon of rendered foie gras fat for flavor. Season with salt and pepper. Stir and set aside.

Pickled Radish

See recipe for Red Wine Pickling Liquid. Set aside 3‒5 wedges.

To serve

Place the sliced duck, chanterelles, and pickled vegetables on a plate and pour the gastrique on top. Serves two.

Other garnishes include

Pickled gooseberry, green strawberries, pickled cherries. It’s easy to substitute any of these as need be. △

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Recipe: The Alpinist's Larder

A preserved whiskey drink spiked with the taste of the summer passed

INGREDIENTS

pickled cherries: 3 pieces preserved whiskey: 60 ml (2 oz) leopold bros. three pins herbal liquor: 20 ml (0.7 oz) lemon juice: 20 ml (0.7 oz) honey syrup: 20 ml (0.7 oz)

DIRECTIONS

1 Combine all ingredients into a shaker 2 Gently muddle the cherries 3 Shake with ice 4 Double strain over ice 5 Garnish with cherries, mint, and lemon peel.

Recipe: Alpine Hot Toddy

Enjoy a warming drink in memory of the summer harvest

INGREDIENTS herb bundle: Thyme, marjoram, sage, lemon peel, mint, sorrel whiskey preserved apples: 30 g (1 oz), diced violet flowers preserved whiskey: 60 ml (2 oz) leopold bros. three pins herbal liquor: 20 ml (0.7 oz) lemon juice: 20 ml (0.7 oz) hot water: 1 pitcher

DIRECTIONS

1 Place all ingredients into a heat-resistant pitcher 2 Add hot water to steep (1‒2 minutes) 3 Strain into a heated mug or glass 4 Garnish with apples and lemon peel.

Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Boulder bartender Jon Watsky making the Alpine Hot Toddy / Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Boulder bartender Jon Watsky making the Alpine Hot Toddy / Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Recipe: Whiskey Preserved Apples

Bag summer for a little while longer. Winter is coming.

INGREDIENTS Honeycrisp or Gala Apples: 2 peeled, quartered, and cored Rye or Bourbon whiskey: 300 ml (10 oz) Honey syrup: 60 ml (2 oz)—1:1 ratio honey:water Thyme: 1 sprig Sage: 1 sprig Lemon Peel: 2 peels Orange Peel: 2 peels Fennel Seed: 3 g (⅔ tsp, 0.1 oz) Clove: 3 g (⅔ tsp, 0.1 oz) Cinnamon Stick: 1 small

DIRECTIONS

1 Blanch (for 2–3 minutes) and shock the apple quarters. 2 Place all contents into a cryovac bag and seal. 3 Using an immersion circulator, poach the contents for 3 hours at 48° C (118° F). 4 Save liquid for the Alpine Hot Toddy recipe.

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Preserving Traditions

Savor harvest flavors well into winter by preserving the simple traditions and the sweetest fruits of alpine summer.

Preserving fresh foods so they will provide lasting sustenance through the cold season has been the stuff of daily life since the beginnings of human civilization—nowhere more so than in the mountains and other places where winter lingers.

Cured, dried, smoked, and salted meats and fish. Buttermilk, kefir, and cheese from fresh milk. Wine, spirits, beer, and cider. Pickles, krauts, jams. Tea, coffee, and kombucha. Many of our favorite foods and drinks are created through preservation and fermentation.

Cultured heritage

Passed down through generations, these basic methods served as important tools for surviving lean times. They also served, and can still serve, as familiar rituals that weave and strengthen family and community ties—and enliven our palates, hearths, and communal tables.

Your grandmother may have canned, but with the industrialization of food in the past half-century, many of us have lost touch with this inherited knowledge. Today, people around the world are paying more attention to what they eat and where it came from, tuning in to seasonal foods grown where they live, and reclaiming the simple labors and rewards of growing, preparing, and preserving some of their own food.

Sour beers, probiotic-rich fermented foods, and artisan pickles and preserves are now mainstays at craft breweries, farm-to-table eateries, even grocery stores. In many ways, it’s the rebirth of a more handcrafted, gastronomically rich world, one you can share with your family and generations to come.

"In many ways, it’s the rebirth of a more handcrafted, gastronomically rich world, one you can share with your family and generations to come."

Craft, quality, and connection

Everyone is evidently busier than ever these days. So why this nostalgic look backward at earlier ways of life and at “slow-food” traditions? Amidst the rush, we intuit the importance of slowing down every once in a while to can, pickle, or bake a pie... or to savor a nice bottle of wine or a great cup of coffee. It’s the only way we actually live in the moment. Instant gratification is rarely authentic and ultimately without value.

Preserving basic foods is often done when there’s a surplus of a food: peak season or a bumper harvest. Gathering in a kitchen with a group of people committed to one project, like jarring ramps or canning tomatoes, is a good source of inspiration. Making your own food and creating foods you can’t easily find elsewhere creates a potent connection. People will always gravitate toward craft and quality.

"Making your own food and creating foods you can’t easily find elsewhere creates a potent connection."

Flavor alchemy

Preserved foods are transformed through alchemical processes that yield bright, distilled flavors that shift, soften, and deepen over time. They are living, breathing things. You never know exactly what you’ll get when you open the jar or the bottle.

"[Preserved foods] are living, breathing things. You never know exactly what you’ll get when you open the jar or the bottle."

Food pros like Boulder-based Chef Colin Kirby (El Bulli, Spain, 2008) know a secret: Preserving makes foods more interesting. Done right, simple methods add new life to the most basic ingredients. For instance, savory fruits pickled with varied vinegars make inspiring elements of a complex dish. The key? They create a balance between fat and acidity, a too-often-forgotten flavor component.

Here, the minimalist chef introduces a few techniques:

White Balsamic Pickling Liquid

INGREDIENTS white balsamic vinegar: 2 parts sugar: 1 part salt: 1 part

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Red Wine Pickling Liquid

(for Cherries and Radishes)

INGREDIENTS red wine vinegar: 1152 g (38 oz) water: 535 g (19 oz) sugar: 254 g (9 oz) peppercorn bay leaf

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Apple Cider Pickling Liquid

INGREDIENTS apple cider vinegar: 2 parts sugar: 1 part salt: 1 part

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Rice Wine Brine

(for Green Strawberries and Gooseberries)

INGREDIENTS rice wine vinegar: 340 g (12 oz) sugar: 340 g (12 oz) water: 200 g (7 oz) lime juice: 90 g (3 oz) bay leaf mustard seed peppercorn

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher until sugar is dissolved. Let cool and set aside.

A note on processing, storage, and safety

The vinegar and spices in these recipes make all the difference. They give fruit and vegetables new life and provide inspiration to any chef. Pickling unique ingredients such as green strawberries and gooseberries gives great acidity and texture to classic dishes like duck and chanterelles.

The vinegar also allows for processing (boiling and sealing the jars to prevent spoilage) to occur, and it ensures the pH is below 4.6. This is very important. When any of these recipes are used for long-term storage, please follow basic canning rules: Sterilize jars and lids, test the pH (general rule is below 4.6), and carefully boil the jars before setting aside. Once these rules are followed, start canning. △

Recipe: Muscovy Duck Breast with Chanterelles, Pickled Radish, and Foie Gras Gastrique

A fine duck dish starring mushrooms and pickled garden gems preserved from summer. Go to recipe »

Recipe: Whiskey Preserved Apples

Bag summer a little while longer. Go to recipe »

Recipe: Alpine Hot Toddy

Enjoy a warming drink in memory of the summer harvest. Go to recipe »

Recipe: The Alpinist's Larder

A preserved whiskey drink spiked with the taste of the summer passed. Go to recipe »

The Tippy Brass Ballerina

A conversation with designer Eero Koivisto of Claesson Koivisto Rune about the accidental making of the dancing brass bowls

Ballerina is a series of unstable bowls in a highly polished brass plate, designed by the Swedish design studio Claesson Koivisto Rune and produced by the 400-year old metal manufacturer Skultuna, one of the oldest companies in the world.

Skultuna, was founded in 1607 by King Karl IX of Sweden as a brass foundry and is still a purveyor to the Royal Court of Sweden, still in the same location. Today, Skultuna works with international designers, including the Swedish architectural partnership Claesson Koivisto Rune, founded 1995 in Stockholm by Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto, and Ola Rune. The firm meanwhile puts equal emphasis on architecture and the design of objects from tableware, textiles, and tiles to furniture and lighting.

One of our favorite Claesson Koivisto Rune designs are the tippy brass Ballerina bowls, manufactured by Skultuna. When looking into a bowl, the polished concave inside distorts the reflection so that the actual shape appears flat. Their convex bottoms make the bowls rock and dance when touched. When in movement, the Ballerina bowls also project “dancing” golden, glimmering light reflections around the room. We spoke with the bowls' modernist creator and co-owner of Claesson Koivisto Rune.

A conversation with architect and designer Eero Koivisto

Above, from left: Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto, and Ola Rune, the three founders and eponyms of Claesson Koivisto Rune Architects

What is the story behind the Ballerina bowls?

Actually, the bowls started with another product brief for Skultuna, which sort of transformed into the Ballerina bowls. What was the downside of the original design—the movement—turned into a design feature when we decided to make them into small bowls.

One can't help but touch the elegant, shiny bowls and rock them. What is the significance of their intentional movement?

We have worked with movement in usually static design objects before—for example PEBBLES seating for Cappellini, SEESAW for DeVecci, and BASSO, MOEBIUS, and BELLE, also for Skultuna. Since the bowls are fairly small, the movement comes across as playful and slightly surprising.

"Since the bowls are fairly small, the movement comes across as playful and slightly surprising."

When you hold a Ballerina bowl in your hands today—your design that came to live through craftsmanship—what goes through your mind... and heart?

What started out as an idea about movement, has turned into a quite beautiful object in itself.

You designed these bowls for Skultuna. In what way is the experience of designing for a more than 400-year-old company unique?

The owner and the CEO are fairly young, so even if there’s a lot of history involved, they are a pretty youthful company and always open to new ideas in design.

Thus far, what’s your legacy in the design world?

I’m very honoured to be asked the question regarding our work, but I wish to pass it on to others, who can see beyond our own studio, to answer it.

What makes you a modernist?

Living in a modernist society.

What does "quiet design” mean to you?

We are very attracted to the idea that objects co-exist in a given context. Our work is not brash or loud, and it functions well together with other things, which can be totally different in their approach. We don’t really like ”look-at-me” objects.

"Our work is not brash or loud... We don’t really like 'look-at-me' objects."

Usually there’s a lot of idea work in a particular design that is only obvious if you know the story behind it. But when you know the idea behind a certain object we have designed, a new depth occurs—kind of intellectual, but not in an excluding way.

On the other hand, we like the idea that you can use our designs for a lifetime without getting bored by them and without having any idea whatsoever why they look, feel, and function a certain way.

"We like the idea that you can use our designs for a lifetime without getting bored by them and without having any idea whatsoever why they look, feel, and function a certain way."

You design accessories for the home. What does “home” mean to you?

Most of our work is buildings, since we are an architectural studio, but we enjoy doing smaller objects and furniture, too. If architecture is our life’s journey, the smaller objects are the nice dinners with friends along the way. So, home is where we live our lives. Wherever that may be.

"If architecture is our life’s journey, the smaller objects are the nice dinners with friends along the way."

What’s most important to you in life?

My family and my work. In that order.

When are you happiest?

At home and at work. In the same order.

Who is your design icon?

I don’t really have icons anymore, but I do admire good work from people I know.

What inspires you as a designer?

Art and music.

What are you working on these days?

About ten different architectural projects—private houses, places for art, apartment buildings, hotels, and about 40 design projects in various stages of their design. All over the globe. △

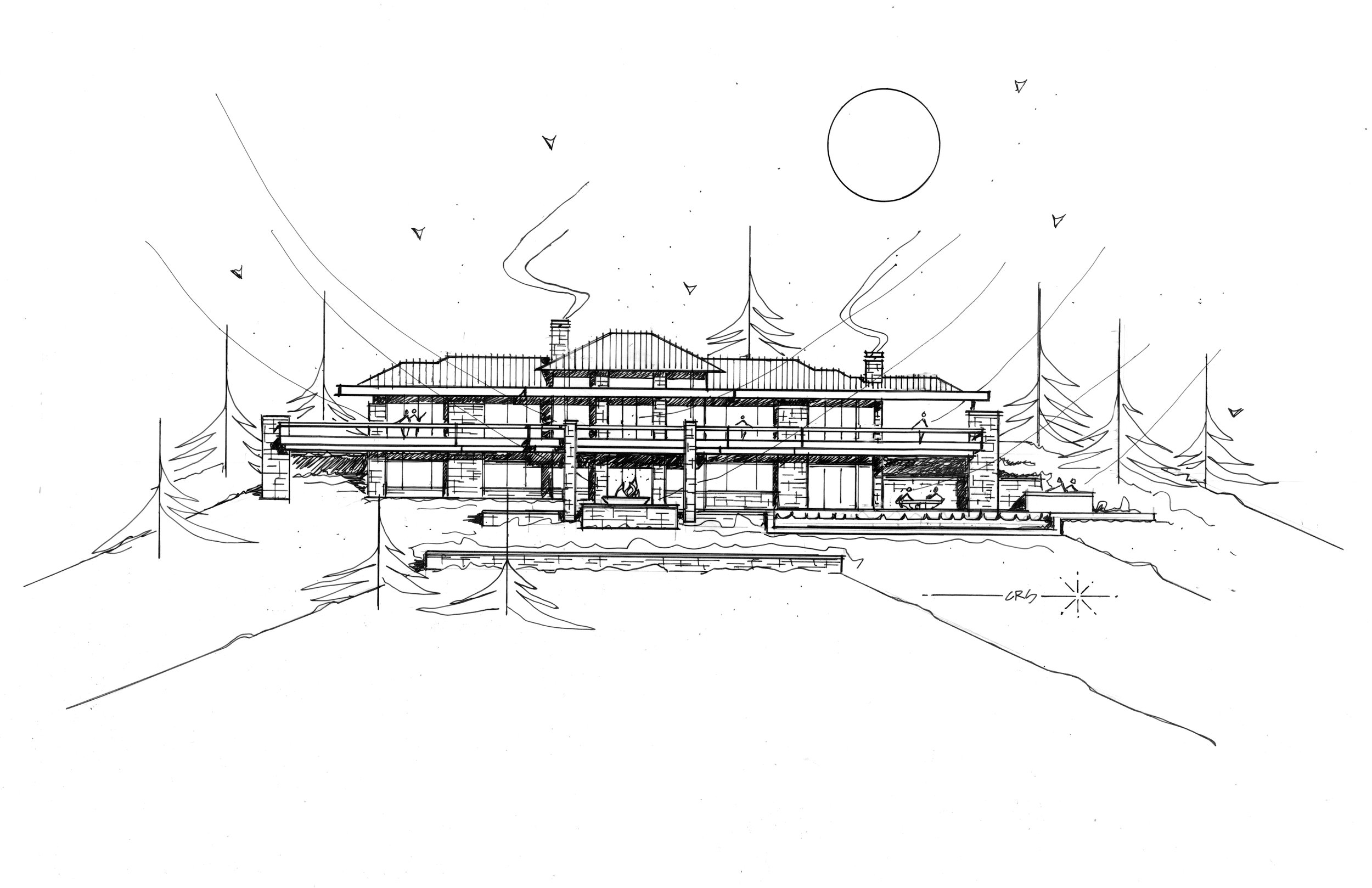

A Dream in Detail

Sharing a deep admiration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work and a devotion to detail, a retired couple builds the mountain home each envisioned before they even married. An intimate look at a dream come true.

Bob and Judy met on a blind date . . . What sounds like the beginning of a romantic love story—which it is—also leads into the inspiring story of two people who, on that first night discovered they shared a passion for architecture, the work of Frank Lloyd Wright in particular, and a lifelong dream of someday living in the Vail Valley, in a warm, modern house overlooking the ski runs of Colorado’s famous winter resorts.

“We wake up every morning and can’t believe we get to live up here,” Bob says today. The Michigan native visited Colorado for the first time when he was seventeen, on a ski trip with his buddies. “I remember thinking, ‘Someday, I want to live out here. Not in a ski-in/ski-out place, where you are up close to the mountain, but in a house with great vistas of snowcapped mountains.”

Forty years later, the man, who spent a career traveling the world as an executive for global brands, stands behind his marble kitchen counter, looking out over Beaver Creek and some of the country’s highest peaks soaring more than 14,000 feet (4,267 meters) above sea level. The dream house he built with his wife of eleven years was carefully sited so the windows of the great room frame the ski runs across the valley perfectly. “We wanted this feeling of a life-size trail map.”

“We wanted this feeling of a life-size trail map.”

Judy, for her part, grew up in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Her mother and father, too, shared a love of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture. “Every month, my father took my brother, my sister, and me to see a different Frank Lloyd Wright house. That had a profound effect on me, and is something we continue to like to do,” she says. “It’s also one of the strong bonds that Bob and I have, because he used to ride around Michigan and go to Frank Lloyd Wright houses, knocking at the doors and asking if he could meet the people.”

“Every month, my father took my brother, my sister, and me to see a different Frank Lloyd Wright house. That had a profound effect on me.”

The perfect plot and a modern master

It took one year to find the perfect lot, 9,125 feet (2781 meters) above sea level, at the end of a winding, aspen-lined road above Avon, Colorado. For an entire ski season after they bought the lot, the two came up from Denver on weekends. “Instead of skiing, we’d sit on the site and envision what our life would be like up here, and how we wanted to live in the house,” Judy thinks back.

“Instead of skiing, we’d sit on the site and envision what our life would be like up here, and how we wanted to live in the house.”

Then the new landowners needed to find an architect who could put their dream on paper. They hit the bookstores. “We were going through architecture magazines, pulling out pictures of homes that looked interesting to us,” says Judy. “And then we realized, it’s all the same architect.” The modern master whose work jumped out at them time again was Charles Stinson of Charles R. Stinson Archi-tecture + Design in Minnesota.

The internationally acclaimed architect had never designed a mountain home before; but having seen his previous work, Bob and Judy were confident he was capable of helping them achieve their dream. “Rare clients I know of who are such students of architecture,” Stinson says about the pair. “We hiked their site together, and we all had a harmony in the way we saw the world and the potentiality of architecture.”

Good design takes time

The couple as well as their architect appreciate Wright’s clean, horizontal lines, his strong sense of flow between indoors and outdoors, and the use of warm materials. Nonetheless, the design was not to be an imitation of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. “Bob and Judy’s house both integrates the materials and the geometry of Wright, but it also brings in a more modern aesthetic and materials and technology,” Stinson says. “We integrated the history of Wright’s contribution with a current, modern architecture.”

The two key design objectives were to maximize the views, and for the house not to pretend to be something it was not. The creative collaboration with Stinson took another four years before the clients felt the design was right. “Good design really does take time,” says Bob. “You get something laid out, and then it takes time to react to it.”

"Good design really does take time. You get something laid out, and then it takes time to react to it."

“I try not to think of it as obsessive compulsive,” says Bob, “but everything makes a difference in architecture.” He believes that paying attention to detail creates warmth and “zen-ness.” Good design is not for everyone to notice, but to recede behind form and function. Yet, a space that feels good and evokes an emotional reaction isn’t happenstance. “Attention to detail makes those details go away, and there is a calming feeling in that space,” says Bob.

Stone on stone

Stone is the protagonist among the house’s natural materials, both on the interior and the exterior. Devoted to detail, Bob and Judy wanted every stone on the interior to match the color and lines of its counterpart outside the glass panel to create unity between the outdoors and the indoors.

Every day for two years, up to ten stone masons worked onsite, hand-cutting and fitting hundreds of tons of stone brought in from Arkansas. “It really was a labor of love,” says Judy. “Three or four of them had been here the whole time, and they ended up being like family members.”

Adds Stinson: “All of us had such respect for each other, and for the site and materials, and a gratitude for the builders and artisans and their great workmanship.”

Of the hill

Constructed by Mark Fox of Fox Hunt & Partners, the 7,200 square-foot (669 square-meter) home sits on seven acres adjacent to thirty acres of open space to the south and east and borders the White River National Forest. Frank Lloyd Wright often spoke about building on the edge of the forest to achieve a sense of shelter.

The house is tucked into the steep mountainside to block the cold winds from the north. The south-facing indoor and outdoor living spaces reap warmth from the sun year round. Wrapping around the back of the house, the 125-foot upper deck over- looks the pool patio down below, providing covered and uncovered gathering spots. The resulting microclimates provide a comfortable place to sit outside, here or there, upstairs or downstairs, snow or shine.

Following Frank Lloyd Wright’s credo of not building on the hill but of the hill, the house is sited to descend down from an expansive flagstone auto court. “You literally feel more grounded with your environment,” Bob says. “The house would have felt completely different sitting up there.” Now, the home’s horizontal lines follow the horizontal ridge above.

“No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together, each happier for the other.” — Frank Lloyd Wright

Mature aspen trees surrounding the house provide the Wrightian sense of protection and privacy at the forest’s edge.

The welcoming native Midwesterners share their land with Colorado wildlife. Mornings and evenings, deer trot along their natural path, which traverses the property. A pair of foxes likes to hang out by the pool. Because of the down-sloping landscape, birds of prey hover at eye level. “We look out and there will be this huge red-tailed hawk, just stationary, with his landing gear out,” Bob describes. “It’s amazing to watch them at eye level. Usually you only get to see these birds high up in the sky.”

Building into the side of the mountain made figuring out the approach to the house “very challenging,” according to Stinson. “We studied the grades from both directions, and Bob said, ‘Let’s flip the house around.’ It actually worked out better.” The transition from the driveway to the house, which descends down the mountain, now provides an intentional experience. The architect and his clients even climbed on a ladder before siting the house to see the views from where the main level would be. “We wanted to take advantage of a sequence of experiences, so when you are coming into the site up above, you have a glimpse of what the view is going to be,” Stinson says. “The view disappears when you are in the auto court, which is surrounded with nature—so the uphill side is a grounding experience. Then you walk into the house, and boom, the big views let the spirit soar. You see so far and down the valley that you needed that balance of shelter and release.”

Elevated living from the inside to the outside

Inside, the house offers a different experience and view corridor from nearly every room and angle. The elevated interior design reflects the warm colors and materials of the Rocky Mountains throughout.

The main level’s great room and hearth room truly maximize the expansive ski-slope views the owners hoped for. “I can’t tell you how much time we spent with the surveyor on the siting,” Bob says. “He had mapped out all the peaks and we’d literally stand with the footprint of the house, and we moved it three times before they dug the foundation.” The luxury of time and attention to detail once again paid off. “We’ll get ready to go skiing and put the local news on to see about the conditions, and I sit here and have my coffee and say, ‘Well, I can just look at the actual slopes.”

The overhangs of the roof above the main level’s south-facing windows provide architectural drama but are also part of the house’s passive solar design. “In winter, when the sun is low in the sky, the warming sunlight goes all the way to the back wall, whereas in the summer, when the sun is higher, you get a little bit of morning sun, but then it’s blocked,” Bob says. “We didn’t turn on the air conditioning at all last summer.” Roof solar panels already provided one-third of the electricity, and with the recent purchase of 100 more panels on a solar farm sixty-five miles away in Carbondale, Colorado, all the house’s electricity now comes from solar power.

Entertaining dinner guests and hosting out-of-town friends and family are an essential part of Bob and Judy’s new mountain lifestyle, now that they no longer work “crazy hours” in the city. Thus, Stinson designed the main level for the couple to live and entertain dinner guests. A floating buffet visually separates the dining room and breakfast room while maintaining an open flow so guests at both tables feel connected.

Overnight visitors are known to call the lower level “Bob and Judy’s retreat and spa.” Indeed, guests have their private quarters downstairs, with intimate suites named after the respective resort in view and decorated with vintage ski posters mirroring the very scenery outside the window.

The window seats in the downstairs living room, in fact, are Judy’s favorite spot in the house, as she says the ski slopes look even closer from down here. The communal space with an open kitchen opens up to the sweeping pool patio with an outdoor dining area in the center, a hot tub on one side, and another outdoor fire pit off to the other side, where the family loves to roast s’mores at night.

Integrated into the guest wing are also a massage room, an exercise room, and an exquisitely curated wine cellar. The opposite side of the lower level has a bunk room, where Bob and Judy’s nieces and nephews like to hang out when they come on vacation and occasionally bring along friends.

Beneath the garage and a concrete ceiling are Bob’s pride and joy: a movie theater with Whisper Walls and a high-end listening room that boasts a pair of enormous Genesis 1 speakers. Still, the window-less über-impressive “cool area for the loud things” (as Stinson calls the two rooms) are not where Bob spends most of his time. He likes to sit on the lower deck, looking out over the large saline pool and the ski slopes just beyond. This is, after all, his dream come true. △

At the request of Bob and Judy, we are not publishing their last name or identifiable details about their mountain home's location.

Villas in the Trees

Thailand's enchanted Keemala Resort — architecture hidden in the woodlands

Keemala Resort on Thailand's mountainous island of Phuket features four different villa styles, pods, and pool houses by Bangkok-based Space Architects, with interior design by Pisud Design Company.

Overlooking and the Andaman Sea, Keemala harnesses the history of fictitious ancient Phuket settlers and incorporates the story of four different clans within the resort. The architecture of the four different villa types reflects the skills and way of life of each of the groups. Keemala and its grounds are designed as an expansion of the surrounding landscape, making use of natural features such as mature trees, streams and waterfalls and integrating these into the overall design.

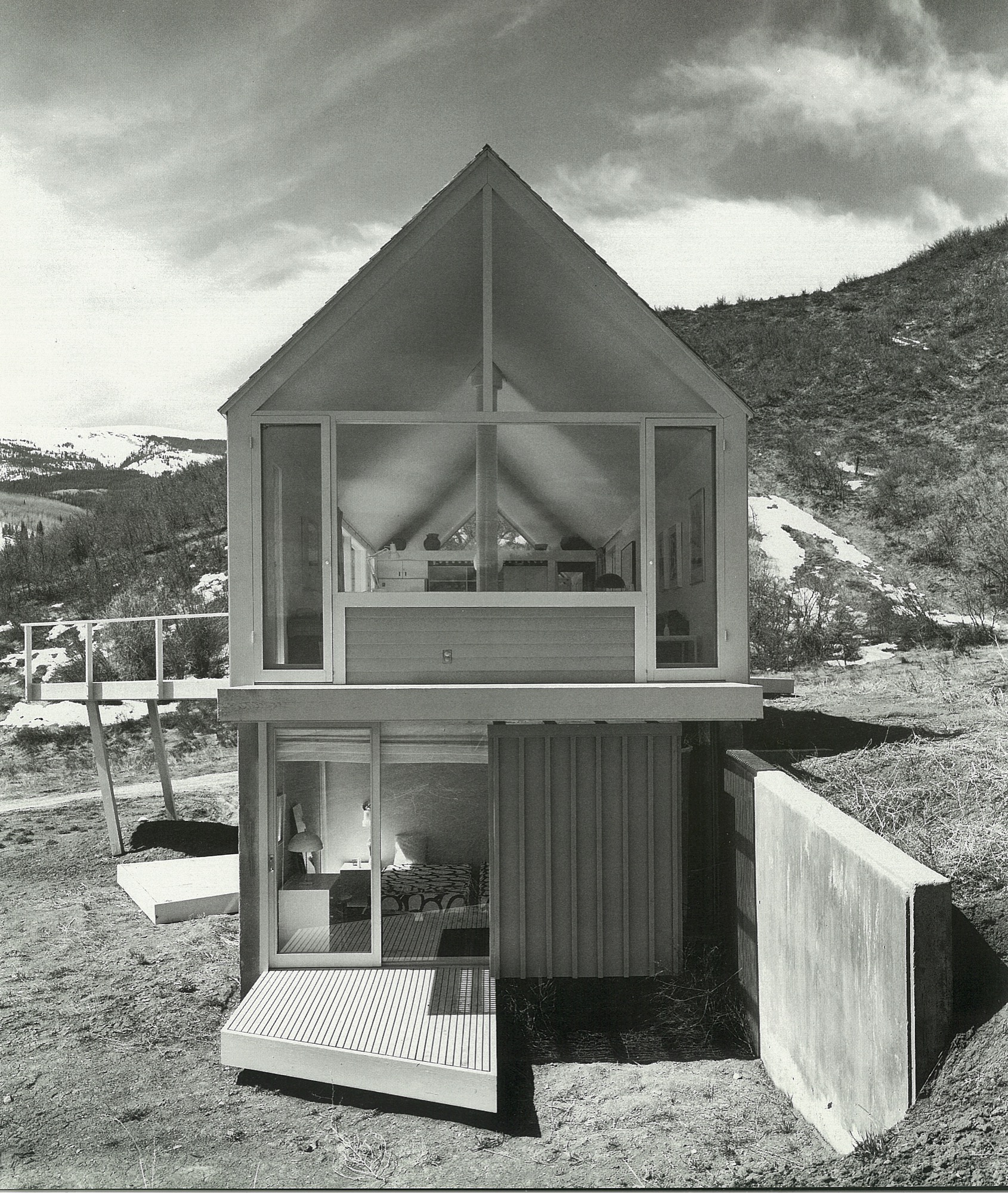

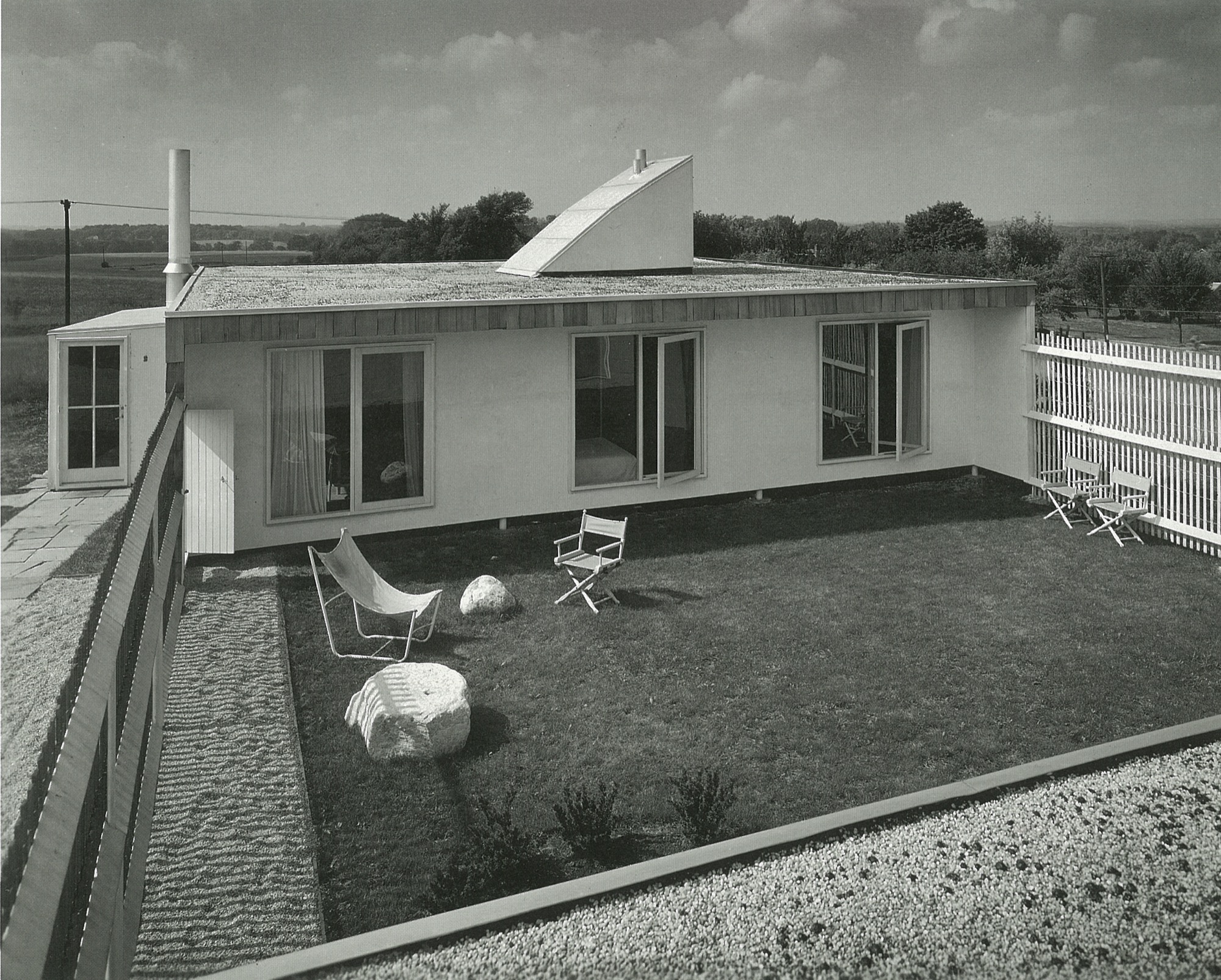

Naked Naust

A dramatic cabin by Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch on Norway's wild Vega Island

Inspired by Norway’s traditional boathouses, Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch plants a cottage into Vega Island’s barren landscape—its design so minimal, it becomes dramatic.

“It’s basically just two ordinary pitched roofs,” architect Erik Kolman Janouch describes the Vega Cottage on the namesake Norwegian island. But the simple elegance of this small wooden cottage that blends so perfectly with its wild and forbidding landscape is, in itself, spectacular—not to mention the boldness and care in siting it there. What’s more, it is exactly what could be expected in this coastal region of Norway.

Not far from the house, by the seashore, stand a few of the colorful traditional boathouses—naust—found throughout Norway’s long Atlantic coast. With origins in the Viking era, this building type has withstood the test of time and weather with the island’s extremely rough climate. So, looking for another architectural typology for the Vega Cottage seemed like a futile enterprise for its Swedish architect of Kolman Boye Architects in Stockholm.

Casual observers might also miss the second most striking architectural feature of the Vega Cottage—its windows. At first, the house’s windows might appear like ordinary rectangular openings in a wall, covered with glass. But that’s just scale and perspective playing tricks, since the barren landscape of Vega Island offers little else of human scale for comparison. Standing directly in front of the house—where one’s cheeks quickly turn rosy from the cold Atlantic wind—an adult visitor can stand head to toe in the huge windows and absorb the majestic landscape. Buffeted by the wind and swept away with the dramatic views, one realizes that the windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island.

"The windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island."

A Place Apart

Vega is home to 1,200 people and lies roughly an hour by ferry out in the Atlantic from the tiny city of Brøn- nøysund on the west coast of Norway, just south of the Arctic Circle. The cottage’s site is not much more than a farmstead, marked on the map as Eidem.

This is where the man who commissioned this house, Norwegian theatre director Alexander Mørk-Eidem, has his roots. Born on the island, he has lived most of his life on the mainland, and for the past ten years in Stockholm, Sweden. That is also where he met the architect. He approached Kolman with his idea for a country house or a cottage, commonly known in Norway as a hytte. A small and simple residence in the countryside where you go on weekends and during vacations to relax and enjoy nature... something with which Norwegians, blessed with a country of stunningly beautiful mountains and fjords, seem to be obsessed.

The end of the world, as Vega feels, seems like the obvious place for a director of the stage to seek peace and quiet and to find inspiration. Mørk-Eidem jointly owns the house with his siblings, a brother and a sister who now live in London and Oslo. The house is intended as a place for solitary retreats, but also for family gatherings, since an uncle and cousins still live on Vega.

“Inside, the house is neutrally furnished to allow for nature to...” Mørk-Eidem starts to explain when I visited the house, only to get interrupted by his architect: “It’s like three paintings. There is no need to adorn the walls.”

The Cast of Characters

What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape. It doesn’t take a stage director to reach that conclusion. Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless. On the other side of the windows of the combined living and dining room lies the mighty Trollvasstind mountain, 800 meters (2,625 feet) high with a ridge that’s hidden behind milky white clouds. In the other direction the Atlantic Ocean and open sea stretch all the way to Labrador in Canada.

“What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape... Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless.”

Kolman recalls the first time he came to the island and the site, after having accepted the challenge of designing the house: “I went there in January, which is the worst time of year, weatherwise. It was pitch dark and freezing. Shockingly freezing, really. I wasn’t prepared for how harsh the climate would be.”

But nature can be kind on Vega, too. At milder times of the year, when the tide comes in during the day, the sand at the shoreline that had previously been heated by the sun warms the shallow water, allowing for some appreciated beach life. But the weather changes quickly here: from calm to a wind you can lean against in a matter of minutes. It is wise never to leave the house without the proper attire: mittens, Wellingtons, and a decent raincoat.

In contrast to the adventurous landscape and weather of Vega, the cottage interior is serene with a neutral color palette to enhance the tranquil atmosphere. Practically everything inside the house, from the walls to the bed linen, is white. The architect thinks it gives the house a hotel-like quality.

The Right Stuff

Kolman met his client through a mutual acquaintance in Stockholm. Mørk-Eidem had been looking for someone to build the house for quite some time. Realizing what a challenge it would be on this particular site, he pictured someone young, eager to take on the assignment for the experience, and Kolman fit the bill.

In addition to being one of the partners of Kolman Boye Architects, Kolman also runs a construction firm. A lucky combination since all the contractors Mørk-Eidem approached for a tender had simply refused to answer. “There was nobody who could see any joy in trying to do the impossible,” Mørk-Eidem explains.

Kolman proved to be different. In the Vega Cottage he saw nothing but an enticing challenge. Building the house on Vega was possible, but it took five years and twenty-three Stockholm-Vega round-trips by car for the architect. A total distance, he figures, that roughly equals a trip around the equator. True or not, one trip by car from Stockholm to Vega is long, time-consuming, and not very pleasant.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house had always stood on this site,” Kolman says. “What fascinates most people who come here is that you get the feeling that it’s grown out of the bedrock.”

Building on the bedrock and being gentle with the landscape also made the construction difficult. A road had to be built to the site, and building material laboriously towed over the bedrock the house stands on—not to mention the efforts to transport and install the windows. The panes are 40 millimeters (1.57 inches) thick to withstand the storms and high winds that would shake and shatter thinner glass. Residents can enjoy the spectacle outside from a quiet, warm, and cozy house, cheered by the hearth that is the heart of the lower-level’s social area. “They’re not something you can break easily,” Kolman says about the windows. “In fact, you can jump on them and nothing will happen.” Staying at the Vega Cottage, I was glad the project was graced with such a persistent architect-builder—the landscape is beautiful, but I was happy to keep the elements of nature where they belong—on the other side of the glass.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house has always stood on this site.”

Other than the pitched roof, this is a rather minimalistic house—or as Kolman says, “There is nothing that juts out, so there is nothing for the wind to grab on to.”

There is not even a railing around the terrace outside the lower level’s two bedrooms. “My sister wondered when they would be put in place,” Mørk-Eidem says. “They never will be,” he declares, adding, “This is a childproof house in the sense that nothing can be broken.”

If nothing can get broken, theoretically nothing will need to be fixed. To keep maintenance on the house to a minimum during holidays and vacations, Mørk-Eidem and his architect opted for weatherproof solutions for the house. At one stage in the project they considered black facades. But when I visited, a year after completion, the unpainted facades, which were only treated, already had their gray patina. Houses age fast on Vega.

“Houses age fast on Vega.”

The cottage owes much to vernacular architecture, but the local building tradition has always emphasized protection from the elements of nature. The island’s old buildings, placed wherever there is shelter from the storms, all turn their backs to nature and to the extreme weather. “You get very unsentimental living out here,” Mørk-Eidem tells me. “You get used to this nature, and you look at it as a kind of antagonist.”

“You get very unsentimental living out here.”

He proceeds to tell how his father reacted when he first came to the house. As an adult, Mørk-Eidem senior moved to Oslo and hadn’t lived on the island for decades. “At first, he was suspicious,” Mørk-Eidem recalls, “because he’s never been used to sitting inside and just admiring the view. For him it was a really different experience to come to a place he knows so well but to see it from an entirely new perspective.”

Hearing that this outpost can give even natives new perspectives is a testament to the qualities of this house that makes the architect say, without the slightest hesitation, that he would gladly take on the logistical and psychological challenges of an assignment like this again. △

Fire / Wood

His Nordic German upbringing, traditional Swiss carpentry training, and the Bauhaus Manifesto deeply influence Canada-based designer and furniture-maker Nicolas Meyer as a craftsman and intellectual

Nicolas Meyer’s approach to design and craftsmanship is firmly anchored in his traditional Swiss training as a furniture maker and balanced with his Bauhaus-influenced intellect.

Nicolas Meyer is not one thing, not from one place. Born in Germany and raised in Switzerland, the multifaceted founder of Nico Spacecraft has put down roots as an artist, designer, woodworker, and furniture-maker in British Columbia, Canada.

A sincere dialogue about design and wood quickly reveals the man is at once both an intellectual and a craftsman. No surprise, he seeks balance in everything he does.

Meyer grew up in Hamburg, Northern Germany. With a real estate-developer father and an antique-collector mother, the boy was exposed to architecture, construction, and fine furniture throughout his childhood. The parents separated when he was ten, and he moved to Switzerland with his mother.

In 1991, Meyer lived in Vancouver for half a year to improve his English. He returned to Switzerland to complete a traditional four-year apprenticeship in furniture-making, which he finished a year early by virtue of prior education, excellent marks, and extraordinary talent. All this time, British Columbia remained on his mind.

The decision to return four years later to settle in Canada was spiritual as much as rational. “Things just feel right, and you find your place where you want to build your life,” Meyer reflects. Having spent the first ten years of his life in Hamburg, he was influenced by the ocean, water sports, the city’s harbor as “gate to the world,” the metropolitan lifestyle. In Switzerland, where he lived until age twenty-five, he later fell in love with the mountains and skiing. “Vancouver combines all of that. This is one of the few places where you can probably ski and kayak on the same day,” says the expat. “On top of that, this was my place. I grew up in this tension between Hamburg and Switzerland. As a kid who is constantly in between these two places, you wonder, what is your home.”

Today, Meyer is a designer, a woodworker, an artist—his creative drive the common thread. As child, he wanted to become an inventor, broke a lot of things, took them apart to understand them. In his later teens, he eventually began fixing things. “I also read a lot. I came to design and wanted to study architecture,” he says. He originally planned to study interior architecture in London after his apprenticeship in Switzerland. By that time, however, he’d already lost his heart to Vancouver. “I was too impatient and thought, I’ll go to Canada and find my way to design with what I have.”

His apprenticeship as well as the subsequent decision to practice, not study, were driven by his readings: the Bauhaus philosophy in particular—“Most of all, Walter Gropius and his manifesto, which expresses how the core of creativity can only come out of understanding a craft,” says Meyer.

“For art is not a profession. There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman.” — Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Manifesto, 1919

The Bauhaus Manifesto guides Meyer to this day, everyday. Together with his wife, Jess Meyer, he runs Nico Spacecraft, a small design studio with integrated wood workshop that produces kitchens and baths, furniture, custom spaces, and architectural elements. The company’s full-service design division has its own name: Baumhaus Atelier—presumably a nod both to Meyer’s enthusiasm for all things Bauhaus as well as to his passion for trees (Baumhaus is German for treehouse). “It’s about striking the balance between being in front of the computer screen or a sketchbook and actually being in the shop and working with materials,” he says. “When I spend too much time in the shop, building all the time, I itch to sit down and sketch out ideas, whereas when I’m in the office too much, I lose touch with the reality of structure, weight, and smell, and how things actually connect.” The creator admits he usually knows he has overextended himself at the drawing board when he starts designing things that don’t work in the real world.

“When I spend too much time in the shop, building all the time, I itch to sit down and sketch out ideas, whereas when I’m in the office too much, I lose touch with the reality of structure, weight, and smell, and how things actually connect.”