Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Seduction Design

Former Eames art director and CommArts co-founder Richard Foy muses on the bowerbird’s incredible construction and composition skills and human design

Design is everywhere. People have always valued design expertise, even dating back millions of years to the first tools ever used and now recently unearthed. From the harnessing of fire, clubbing of opponents, carrying water in vessels, throwing spears, and using fur blankets, to riding around in Teslas, we like and rely on design.

Daily design

Today, most everything we have, use, want, and need is designed. We have even designed robotics and programs that design things for us. Every time we dress ourselves, email, make a meal, buy things, plant gardens, do a spreadsheet, we become designers. We are making functional decisions based on what we need, what it says, and how it feels. We are reflecting ourselves and how we want to be perceived through our choices. We are designing. We do this daily for work, pleasure, and living, without pause or conscious thought.

Design is intrinsic to art, invention, and creativity. Design is different from art because it tends to focus on underlying structure, function, or purpose more than personal expression—although the best designs have or tell a story that expresses a point of view. We rely on design for practical solutions to everyday problems or issues. A lot of design is offered as a service to help people, businesses, and institutions.

Design and cultural creativity advance humanity

The professional practice of design creates solutions and makes the places, products, and market of the future. We value communities where there is a high level of design and cultural creativity that responsibly advances society. Florence emerged during the Renaissance because of its design and art contributions, which we still value 500-plus years later. Humanity, backed by theology claims dominion over all species. From the human (not particularly Biblical) view it’s based on our historically unmatched and singular ability to design, make, and use tools.

Amorous architecture

A newly recognized and different breed of designer is practicing in Australia and New Guinea. They have gained notoriety by becoming experts on the art of seduction. Their primary design passion is the field of amorous architecture, interiors, landscaping, and the courtship arts of song and dance. The places they build attract, entertain, charm, and seduce females. They are among the best in that business and are studied and respected worldwide for their thorough design approach, execution, and resulting social benefits. They have perfected their skills over thousands of years, which further attests to their expertise and effectiveness.

"Their primary design passion is the field of amorous architecture, interiors, landscaping..."

Attraction by design

Creative human designers like to wear black clothing. These designers prefer feathers, as all are members of the bowerbird family. Their closest kin on this continent are ravens and crows. Some bowerbirds are a bit larger and live a little longer, up to twenty-seven years.

Another consideration before comparing bird designers to human designers is the possibility that their design creativity may emanate from the same source. Design as a noun identifies something intentionally made or resulting from an idea or plan. Design as a verb is an act or the process of making, visualizing, creating, or turning an idea into a new reality.

The design process, whether painstakingly thoughtful or impulsively spontaneous follows a pattern. Stasis, curiosity, imagination, question, attempt, failure, learning, success, change. Change as a causal dynamic is as present in the space, time, matter, and energy of the cosmos as it is in the buzzing subatomic and atomic particles of our biological cells. The question is what or where is the intention responsible for the nonhuman-made, natural world?

Source and cause of design

There is a Zen koan that says, “Learn to listen to the wisdom inside of a rock.” Are humans and other biological creatures all part of the same dynamic forces responsible for change? Are we all variants of the same energy that cannot be created (designed) or destroyed but only transformed? Is change the cause not just the result of creative design? Does the bowerbird follow the same design impulse as do humans? Our link may be that we were all designed by the same cauldron of the cosmos 13.8 billion years ago. We are the same stardust particles that were floating around then but reconstituted by evolution, physics, gravity, thermodynamics, and chemistry. Maybe bowerbirds, rocks, and everything is caused by constant flux of creative change, at one with the universe.

"Maybe bowerbirds, rocks, and everything is caused by constant flux of creative change, at one with the universe."

Male bowerbirds are renowned for designing painstakingly ornate, complex, and personalized bachelor pads and performance routines to attract females for amorous encounters. A female bowerbird requires and insists on unlimited choice and opportunity to select her mate based solely on her assessment of how well the male earns her trust and displays his creative intelligence. The stakes are high. Seventy-five percent of females in one study area visited only the one same bower out of dozens of offerings before mating.

Older, more experienced males will succeed with dozens of females in a single breeding season while younger males will seduce only a single one of his dozens of visitors. A lot rides on the design quality of the bower; its form, color, and execution, followed by a concert and dance performance. Providing a sense of comfort in combination with self control, respect, and restraint gains reproduction rights that help determine the survival of their species. Everything is designed for the pleasure of the female and winning her mate-selection preference.

Bower architecture

A bower is defined as a secluded place, often in a garden, enclosed by foliage or an arbor. It can also be a summer house or garden cottage, an inner room, or a boudoir. Lovely.

Males build three types of bowers: “maypoles,” “mats,” and “avenues.” “Maypoles” can be single- or double-masted towers. Some are built around a young sapling that becomes its centerpiece. Others have curved walls that frame and showcase the awaiting male. They are dotted with colors that help their visibility and location of the bower below. Sometimes a roof is designed immediately below the tower, which provides shade or privacy in the bower. Towers stand out from the brush and call attention through their distinctive forms.

“Mats” are landing pads made from collected plant materials such a fresh green moss that has been carefully laid and ringed with individually selected and arranged ornaments; making, if you like, the equivalent of an oriental rug. It may contain fresh leaves, petals, owers, snail shells, bits of foil, candy wrappers, pebbles, glass shards, fruit, colored plastic utensils, bottle caps, can pull-tabs, all of the same color or predetermined mix of colors. One researcher found a glass eye in a bower, undoubtedly a very distinctive and intentional treasure piece ripe with symbolism.

“Avenues” are longer and narrower mats that seem to function as landing strips; again, they are ornately marked with color-coordinated found objects. Airport towers, landing pads, and runways would be the human architectural equivalents.

All three schemes sport specific colors that may be a single dominant color or an arrangement composed of multiple colors. Blue seems popular as evident when searching Google images. All are designed to be spotted from the air by mate-seeking females. These are not unlike the bright signs at Saturday night social gathering places and night clubs.

The colors of decorative elements that males choose for their bowers match the preferences of females. Male bowerbirds play to their audience and design for their market segment and demographics. Bowerbird species that build the most elaborate bowers are dull in color, whereas the males of species with less elaborate bowers have brighter plumage.

"The colors of decorative elements that males choose for their bowers match the preferences of females."

The design critics

Males are assessed based on the quality of their bower construction. Males with quality displays achieve mating success, suggesting that females gain important benefits from mate choice. Bowerbird ornamentation is perceived as a sexual indicator of general health, intelligence, and disease-resistant heritage.

The various twig fences, arching walls, roofs, and decorations get painted or stained by colors made by chewing plants and adding charcoal with saliva. Lastly, objects are sometimes arranged by size, large to small, that create a false perspective to hold attention and gain the advantage of more time spent. Perspective also makes the awaiting male appear to be a bigger and better mate.

Females search for mates by visiting multiple bowers, returning multiple times, watching his elaborate courtship displays, inspecting the quality, and tasting the paint the male has made and placed on the bower walls. Many females choose the same male, and many underwhelming males go without mates. Females choosing top-mating males tend to return next year and search less.

Bowers take weeks to design and build, are constantly refreshed, and their color elements are rearranged with bright, shiny ones. Males will also do recon flights to inspect their competition and steal whatever bauble would make their bower more attractive.

Showtime

Once the stage has been set and a visitor lands nearby, it's showtime. These Justin Timberlake males must know how to dance and sing in order to seal the deal. Male bowerbirds are superb vocal mimes. They have been known to imitate pigs, waterfalls, and human chatter. Some bowerbirds mimic other local bird species as part of their own concert. Then the male has to strut his stuff, and strike outlandish poses while dancing and singing to lure his guest into the bower.

A female chooses to visit only bowers that appeal to her. She will land close but far enough to avoid feeling threatened. When she comes closer and stops she may allow the male to approach and mate. A too-eager male will fail. Males only succeed when the visiting female feels comfortable and protected from more aggressive males.

Imagine if every human male had to individually design his architecture, build it alone, lay out a garden, design the interiors, furnish it, paint it, maintain it, sing, dance, and strike poses, or he wouldn’t even get a date!

The social implications of the bowerbird species have always been based on consideration of the female societal role. Only in the last few decades have some western societies realized the importance and significance of women to civilization. Today, there are more women on the planet, more women in the workforce, and in the educational system attaining higher academics than men. CEOs estimate that 80 to 95 percent of all consumer spending is determined by women—homes and their locations, insurance, appliances, furnishing, food, clothing, schools, and even tools.

Bowerbirds seem to have long designed for a sociology that has always given females due respect, something that has taken far longer in human societies.

“Bowerbirds seem to have long designed for a sociology that has always given females due respect, something that has taken far longer in human societies.”

The bowerbird model is a classic lesson on how successful design is doing the best you can, with what you’ve got, in terms of what social values you encourage through design.

Richard Foy, former art director for Charles and Ray Eames and founding partner of CommArts design firm, has designed many brand identities and places worldwide, including Madison Square Garden (New York City), O2 Dome (London, UK), Pearl Street Mall (Boulder, Colorado), LA Live (Los Angeles, California), and the branding for Spyder Sportswear, and Star Trek — The Motion Picture.

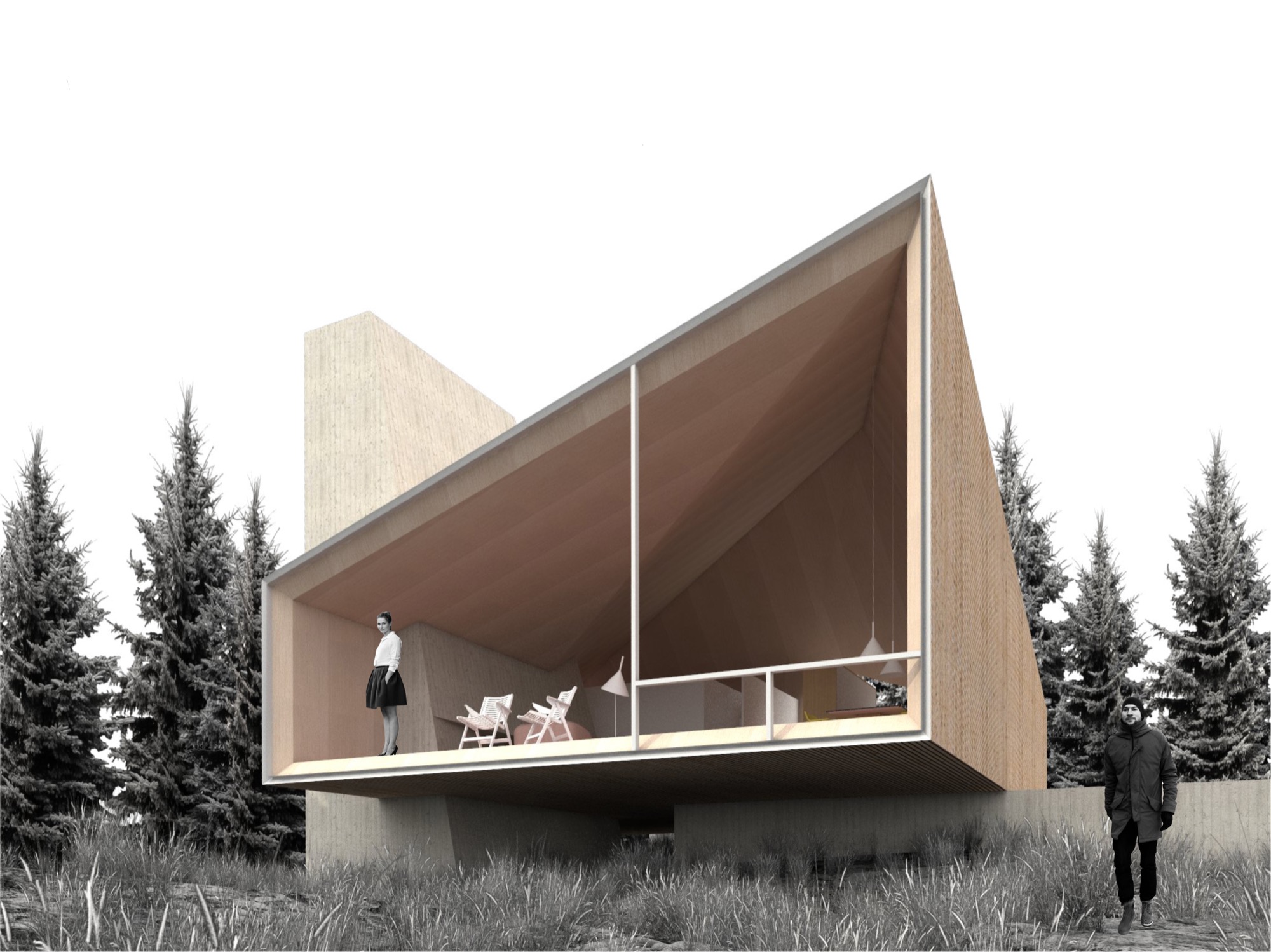

Camera Lucida

An artist's atelier becomes a looking device into the Austrian landscape

The small studio Vienna architect Christian Tonko designed for an artist friend becomes a looking device into the landscape, set in the foothills of the Austrian Alps.

The minimalist studio in Austria’s Vorarlberg region is a visual device in itself that frames the surrounding alpine landscape in two directions. In addition to a single skylight in the roof, the bilevel space has two vertical openings: The tilted glazing to the southeast lets in optimum sunlight, modulated through exterior screens. On the lower northwest end, a system of weathering steel frames allows the artist, who works in traditional media, to hoist up bronze sculptures outside and suspend them in his direct sight in front of the glass. The sculptures also receive their natural patina this way. The artist uses the upper level for sketching and painting in watercolor and the lower level for working on larger canvases and for sculpting.

Architect Christian Tonko’s choice of raw and untreated materials contributes to the character of a workshop. The interior surfaces are raw concrete, raw steel, and untreated oak. On a tectonic level, the structure responds to the descending site.

A Conversation with Christian Tonko

For whom did you design Camera Lucida?

The artist is a family friend. He recently retired and now wants to concentrate on art. The wish for his own studio has been present for many years . . . until it finally happened.

How is the space being used?

His desire was to create a space that is focused on creating art, yet, at the same time is also suitable for reading a book and looking at the landscape. It’s a small studio for drawing, painting, and sculpting for one person. It’s also intended to be a space for retreat and contemplation.

"His desire was to create a space that is focused on creating art, yet, at the same time is also suitable for reading a book and looking at the landscape."

The structure’s design is inspired by an ancient optical device, the eponymous camera lucida. What's the story behind the name?

Historically, the “camera lucida” is an optical drawing aid. It enables the artist to look at an object and a piece of paper simultaneously and, thus, facilitates tracing the object. At the same time, the term can be literally translated to signify “bright chamber.”

What was your original vision for the design of the studio?

At the beginning was the idea to build a small factory. This is where the semi-industrial character of the design stems from.

"At the beginning was the idea to build a small factory."

How did that initial idea evolve into the final design?

This idea of the small factory influenced the design on various levels. It influenced our choice of materials and surface textures but also directly informed the form-finding process. The volume is basically a box with a skylight, just like an archetypical factory building. Then it is set into the hillside and, therefore, the final appearance comes into being.

What’s it like to be and to work in the space?

It is a calm and bright place. The landscape is very present, but it is easy to focus on work and tune out everything else.

What is the synergy between Camera Lucida and its gorgeous mountain setting?

The building itself acts as an optical framing device, so the views are very clearly framed. At the same time, the building is directed towards the sunlight. A great amount of light floods in through the south-facing tilted glazing, which demands exterior sun protection. So sometimes the building is completely closed and the view is blocked.

The Alps are very close, as the site sits at the end of the Lower Rhine Valley, which means it is at the foothills of the Alps. But the building intentionally looks away from the mountains towards Lake Constance. Moreover, the site next to it is inhabited by four Cameroon mountain goats. They are grazing right in front of the window, which is a great feature as it creates a calm and relaxed atmosphere.

What’s on your drawing board right now?

I am currently working on a building that serves as a base for ski tours. It’s located close to the Camera Lucida project, but at a much higher altitude, in a great mountain setting. △

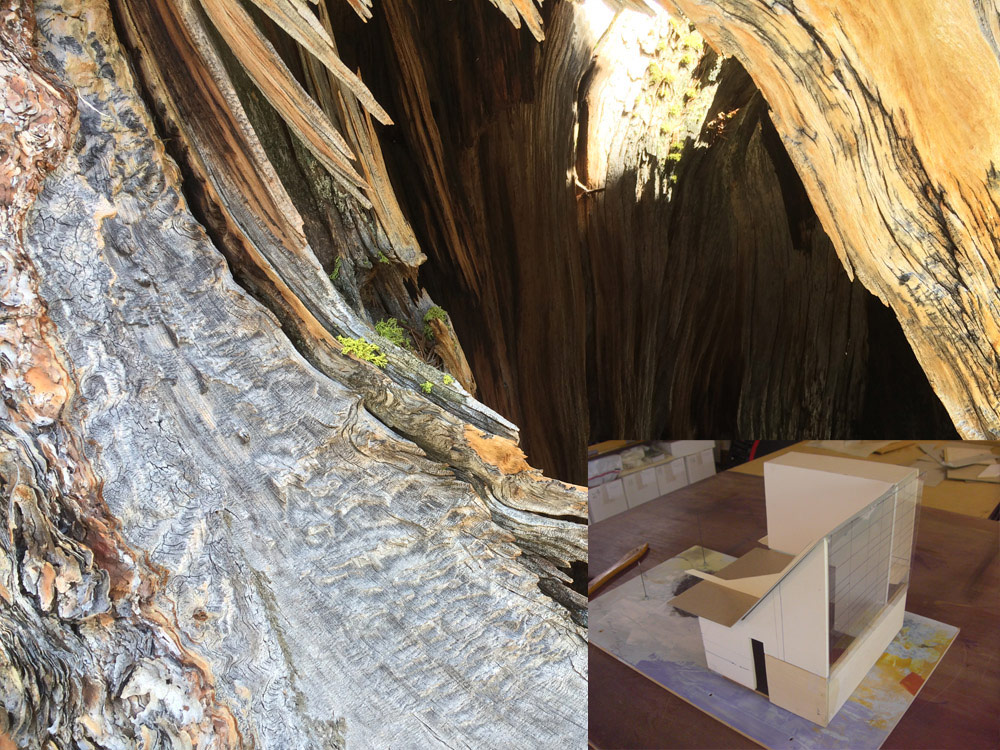

The Tree-Hugging Woodworker

A portrait of California furniture-maker Sean Woolsey

Sean Woolsey loves trees. He celebrates the perfect imperfection of the trees' inner beauty by making wood furniture by hand in California.

Woolsey, now in his early thirties, has always made things. From sewing clothes to building skateboard ramps to baking bread. In 2010, he began making furniture, out of curiosity more than anything else. He deconstructed old furniture to learn how things are made. The first real piece of furniture he built himself was a writing desk for his then-girlfriend. She liked the gift, evidently. She married him.

Woolsey’s work and life is strongly influenced by the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which recognizes the beauty of imperfection as imprint of time. To the wood artist, wabi-sabi is embodied in the naturalness of the uneven, asymetrical touches to remind us of our own and the trees' perfect imperfections. In contrast to mass-producing furniture, which can take away these imperfections, Woolsey chooses to show the truth and rawness of wood, worked by hand.

The California native, who admits to obsessing over the quality of every piece that leaves his atelier, has always been captivated by the beauty of nature’s artistry and gains inspiration from the grandeur of a mature tree and the elegance contained in its wood. In his work, he has stayed true to the same simple ideal over the years: He designs and makes things he wants in his own home. And today, that's the place the entrepreneur shares with his wife, Sara, in Costa Mesa, California.

We caught up with the designer, furniture-maker, and fine artist only a short time after the birth of his daughter, Ondine, to talk about what home means to him, what traditions make his his modern products timeless, what inspires his designs, and more.

A conversation with Sean Woolsey

Who are you, in a nutshell?

A husband, father, artist, woodworker, tinkerer, artist, businessman, creative, friend, surfer, ping pong enthusiast, amateur knife-maker, bread-maker, pizza-creator, dreamer, risk-taker, traveler, tree-lover, ever curious human.

How did you grow curious about designing and making furniture?

It started very naturally and slowly. I was burnt out on making clothing and running my own clothing line. I was drawn to creating things with my own hands and to being more connected with what I was making, instead of just designing it and having someone else make it. I have a real obsession with creating, whether it be a pizza oven in my yard, furniture, a knife, or my own house.

"I have a real obsession with creating, whether it be a pizza oven in my yard, furniture, a knife, or my own house."

What inspires your designs?

So many things and people, but mostly the inspiration is rooted in making furniture that I would like in my own house and like to own for years, not just what is on trend. Much of the inspiration comes from the act of designing and tinkering around. Designs evolve, ideas feed other ideas, and things move with movement.

"Designs evolve, ideas feed other ideas, and things move with movement."

Your modern products appear rooted in tradition. What timeless merit drives your practice?

Functionality, with an utter respect and appreciation of materials and craft.

Is there a continuous theme to your designs?

I don't think so. I think, the only theme is making the best quality products that we can. The theme of materials and design is always changing and progressing.

How do you choose and source your materials?

The wood we use is predominantly American hardwood, such as walnut, white oak, or maple. We purchase most of it locally and occasionally purchase directly from mills, usually on the East Coast. We feel honored to work with wood, and we love trees. We plant a tree for every piece of wood furniture we sell, in honor of the customer, in partnership with the Arbor Day Foundation. It is our way of giving back to nature what it has loaned to us. We also work with steel, brass, glass, leather, et cetera. And we are always looking for new and fun ways to incorporate mixed materials and creating a story with the materials. We are fortunate to have many other talented crafts people locally, who help us with these other materials.

"We feel honored to work with wood, and we love trees."

What makes you a modernist?

The way of thinking about clean, good design that is functional, beautiful, and accessible — and designing to that.

What does quiet design mean to you?

Quiet design to me means designing slowly and enjoying the process. I often enjoy the process more than the end result, as many artists would.

"Quiet design to me means designing slowly and enjoying the process."

Talk about the immensely beautiful fine art pieces in your Copper Series and their synergy with your furniture-making.

The art is a release for me. It always has been. It is the complete opposite of furniture-making, which is very accurate, wrong or right, and precise. The artwork on copper is fluid, free-flowing, expressive, and experimental. Mistakes often make it better or more interesting. The Copper Series was inspired by the ocean, and its meaning to me. The series is ongoing and ever-evolving but always the same size and always inspired by the ocean, whether it be the color, movements, or captivating calm or power it holds.

Describe your dream home...

A home that is comfortable, in a beautiful location in the mountains or desert, with treasures that we have collected all over the world, and open to sharing meals with friends and family.

What does “home” mean to you?

A refuge where we can relax, recharge, make memories, share stories, laugh, cry, and feel good about it all.

What’s your favorite place in the world?

Oh, so many. I have been fortunate to travel a lot internationally. I am really drawn to Japan, and their culture and way of life. To me, Japan is simple, humble in its design yet meticulously thought out, timeless in its approach to craft. And the Japanese are the most focused people I have ever met. The mixture of it all is super intoxicating and inspiring.

What’s most important to you in life?

God. My family. Friends. Creative pursuits. Having fun.

Who is your design icon?

There are so many. The short list is Wharton Esherick, Dieter Rams, Robert Rauscheberg, Lloyd Kahn, Sunray Kelly, Jay Nelson, and Jean Prouve.

Who inspires you to be the person you are?

My wife and my friends largely inspire me to be who I am. As iron sharpens iron, they are constantly encouraging me, whether they know it or not.

What is your life philosophy?

This quote by Mark Twain sums up a lot of my life approach: "Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover."

What are you working on these days?

We are constantly working on new designs; right now, some chairs. I am also working on some copper art, as well as a new art series that is going to be really fun. Also, we just had a beautiful baby girl three weeks ago, so... working on that right now (laughs). △

More of Sean Woolsey's work...

Traditionally Modern

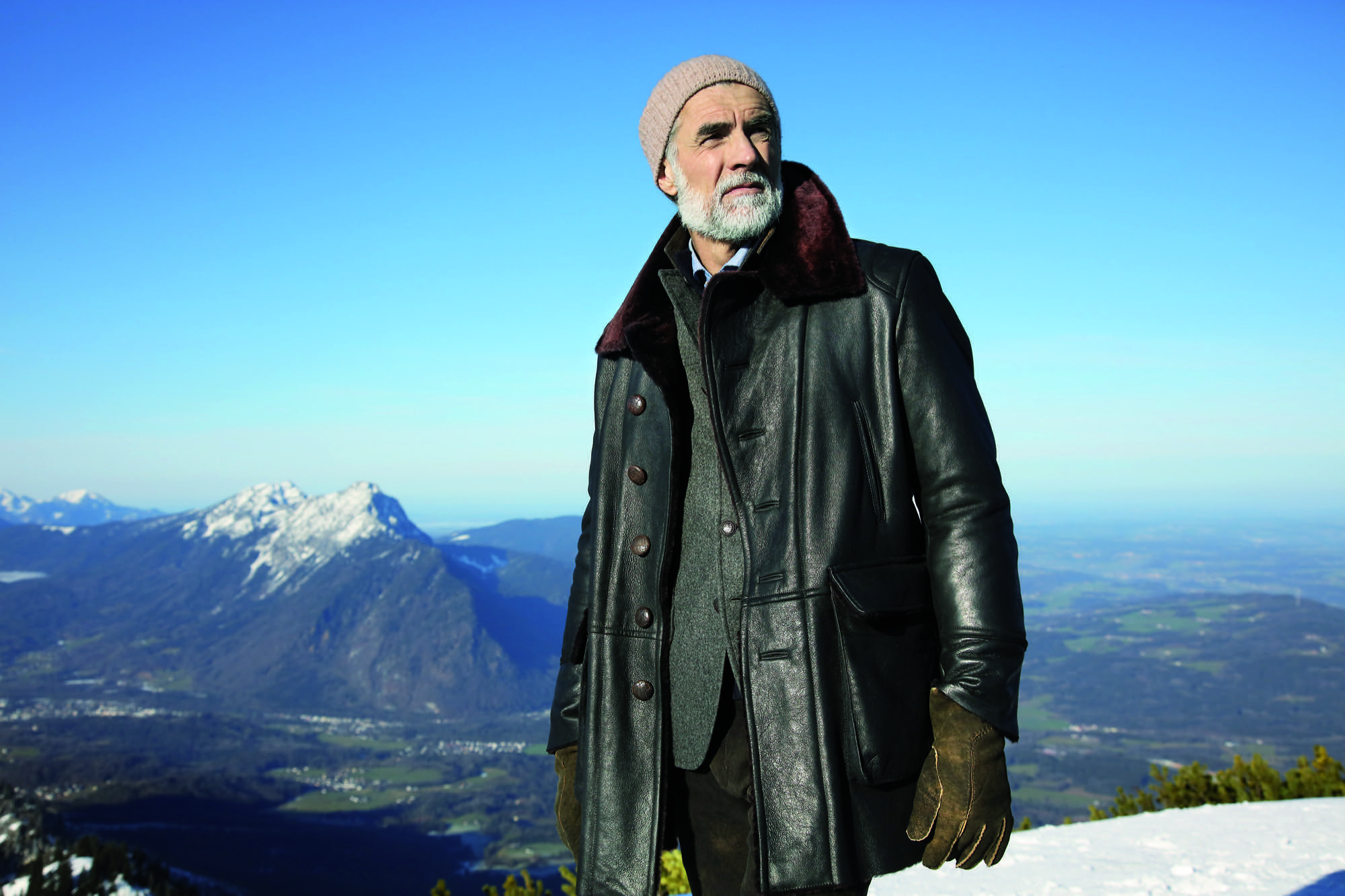

At home with Markus Meindl, the modern mountain man behind Bavaria's traditional maker of lederhosen for the new alpine lifestyle between the forest and the city.

The luxury label Meindl—known for fine, handmade lederhosen—and its CEO, Markus Meindl, deftly move between alpine costumes and fashion, between city and country, between tradition and modernity.

When he was only eight years old, Markus Meindl stitched himself a leather satchel for school. In all likelihood, the result was extraordinary and made the young lad stand out among his classmates. Today, in his mid-forties, the head of Meindl Fashions continues to stand for new ideas, for modernism, for innovation, although or perhaps because he works—and lives—for one of Germany’s best-known companies of tradition.

The urban country home Meindl built for his family near the Austrian border reflects his desire to blend modern and traditional. The minimalist house primarily makes use of natural materials, such as wood and leather, but also a lot of glass and concrete, contrasting with the row of picturesque houses across the River Salzach, on the Austrian side.

The man’s fervent passion for craftsmanship and natural materials is also at the core of the Meindl brand. Along with its traditional lederhosen, the Bavarian family enterprise has long built a multifaceted portfolio of well-crafted leather garments.

The first Meindl lederhosen

It all began when Lukas Meindl, a local cobbler in the idyllic village of Kirchanschöring in Upper Bavaria, tailored his first pair of lederhosen in 1935. Even then, uncompromising quality and the highest form of handcraft were paramount, an art form. The name Meindl dates back even farther, to the year 1683, when Petrus Meindl was officially documented as shoemaker. Markus Meindl is particularly proud of the long family tradition. After he graduated from high school, trained as garment engineer, and apprenticed as couturier, young Meindl didn’t have to be asked twice to join the family company. On the contrary. “That has always been the matter of course for me,” Meindl says. “I practically grew up in the company and have developed a passion for leather material and leather garments at a young age.”

His zeal for creating something new comes from deep within. He has always wanted to develop products he loved himself. Father Hannes Meindl gave Markus the creative freedom and the space to let his youthful zest flourish. “If I’ve learned one thing from him, it’s his free-spiritedness. His honesty in working with the product. But also his honesty in leading his employees,” Meindl says of his father.

At age seventy-four, Hannes is still actively involved in the company wherever an extra hand is needed, whether that’s in sales, in production, or in design. The traditional embroidery, however, is Hannes’s favorite component. Meindl Fashions is famous for its chamois-tanned buckskin lederhosen with lavish hand-embroidered motifs, especially in the Alps, in Austria and southern Germany with their large festivals, such as the Oktoberfest in Munich. Up to sixty hours of manual labor go into handcrafting a pair of Meindl lederhosen. The work is partially done onsite by Meindl’s 120 employees and partially at production sites in nearby European countries, such as Hungary or Croatia. “Every product is designed by us; the know-how all resides in-house,” Markus Meindl says. “We have the most talented team here, the most expensive equipment, and, most importantly, the shortest distances.”

The advantages of in-house, local production are particularly valuable in the development of new products. The Meindl company has long expanded from singularly specializing in lederhosen—albeit traditional alpine costumes are currently experiencing a revival among all ages. “Lederhosen are not a trendy piece of fashion. They span the seasons and are not merely worn to folk festivals and special occasions,” Meindl says. “Lederhosen afford reliability and a sense of security. They rise above time and represent a symbol against calamitous mass production and the consumer society.”

The new alpine lifestyle

Meindl Fashions, with Meindl Jr. at the helm, embodies that pinpoint propensity for this sensibility, the longing for tradition, and for significance. Markus has helped establish the term “alpine lifestyle” in the European Alps; at the very least he has fueled it with products that can be worn on the mountain and in the city: high-quality leather jackets, blazers, sports coats, knickers. Twenty-four years old at the time, Meindl got his breakthrough in 1994 with the creation of a collection for the rebel folk singer-songwriter Hubert von Goisern. It charged the label, the entire fashion industry. A new, modern style conquered the world of traditional alpine garments and found a home at fashion shows like Bread & Butter in Berlin.

Meindl calls his style “authentic luxury”—his own language of design that derives from the combination of craftsmanship and tradition with modern fits and cuts. “Our products are authentic yet also luxurious, because they can never be mass-produced,” says Meindl. “Out of season” is Meindl’s motto. Transcending the seasons, Meindl garments can be worn in winter or on a cool summer night, adding value to each piece.

His message rings true in a fashion world that increasingly appreciates value, sustainability, and timelessness.

Nevertheless, few people really know how multifaceted Markus Meindl truly is. For instance, he designs and produces functional and innovative motorsports clothing in very limited editions for BMW. His leather jodhpurs are worn at the Spanish Riding School as well as by mounted police in Germany. His cousins run the local shoe manufactory, which makes quality mountain footwear and traditional costume shoes. A diverse product portfolio has always been the brand’s strength.

Country refuge for an urban mountain man

Quality stands above all. Timelessness, longevity—and Meindl sought to embody these values in the design and construction of his private home. “I’ve thought long and hard about how I want to design the house,” he says. “It was supposed to withstand time and still be as attractive twenty years from now as it is today.”

His friend Robert Blaschke of Raumbau Architekten in Salzburg, Austria, realized the project. Wood wherever you look, heated Swedish oak floors. Ceilings and walls are covered in 300-year-old oak wood reclaimed from Bavarian barns. The 3.9-meter-high (almost 13 feet) ceiling in the living room and the ceiling in the spa are lined in wooden cubes. The same element serves as armoire and shelving units in the living room and along the facade. The length of the pool—16.83 meters (55 feet)—reflects the year the Meindl company was born; a whimsical reference to tradition interrupted by modern elements. Tradition, lived modernly—that is Meindl’s philosophy. “I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things,” Meindl says. “But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time.”

“I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things. But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time."

Markus Meindl regards himself an “urban mountain man” who lives between the antithetical realms of an urban and a bucolic world. You work in the city during the week. And on weekends, you live in the mountains, where you go skiing, go hiking. “Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.” △

“Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.”

More from Meindl's collections...

Alpine Modern in Its Natural Habitat

Behind the scenes at the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 lookbook photoshoot

We packed up the entire Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Collection and headed up Flagstaff Mountain in Boulder, Colorado.

We stopped halfway up the gorgeous, winding road to the summit. The secluded spot overlooking the city was the perfect place to set up for the shoot. Our good friend Garrett King (@shortstache) behind the lens, and another good friend, talented designer and illustrator Adam Sinda, modeling.

We wanted to capture our Alpine Modern Summer 2016 collection in the most natural and minimal form in which the products were designed and intended to be used. We didn't need a fancy backdrop or expensive studio. We "worked" in Boulder's beautiful backyard.

The goods we design and craft are all about elevating your life. Our mission is to bring modernism to mountain style. From our organic tees and versatile hats to our leather bags coated in an oil finish to repel the elements — our goods are crafted for the mountains but also for daily use and wear. △

More from the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Lookbook...

Nature Is Architecture without Enclosure

Why Alpine Modern has a brief cameo in ml Robles' upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"

From my upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"...

So much of architecture is about replacing what exits. We remove buildings or parts of them, we scrape off land. We like new.

Then we get immensely attached to the buildings that have weathered throughout centuries. Think, Venice or historic buildings like Monticello or Westminster Cathedral. And we want to preserve them, not change a thing.

This is the discussion design enters into when we begin the critical examination of a project’s circumstances: What actually exists? Although the direction that is uncovered in the partí—the basic concept of an architectural design—holds both the physical and ephemeral, it is innumerate. Design, therefore, is a process of uncovering and illuminating the exact constructs necessary to meet the partí. And this is where the eye of the beholders produces the endless solutions to any given design problem. (Put another way, this is also where all hell breaks loose, for who is to say when a partí has been met?)

If architecture begins at the beginning of everything, and it is guided forth by secrets that cannot be told within the mind alone but are revealed by light, then it would seem that in order to uncover and illuminate the exact constructs necessary, design would have to continuously trace back to origin, to tapping the feeling that instantaneously shoots into the infinite.

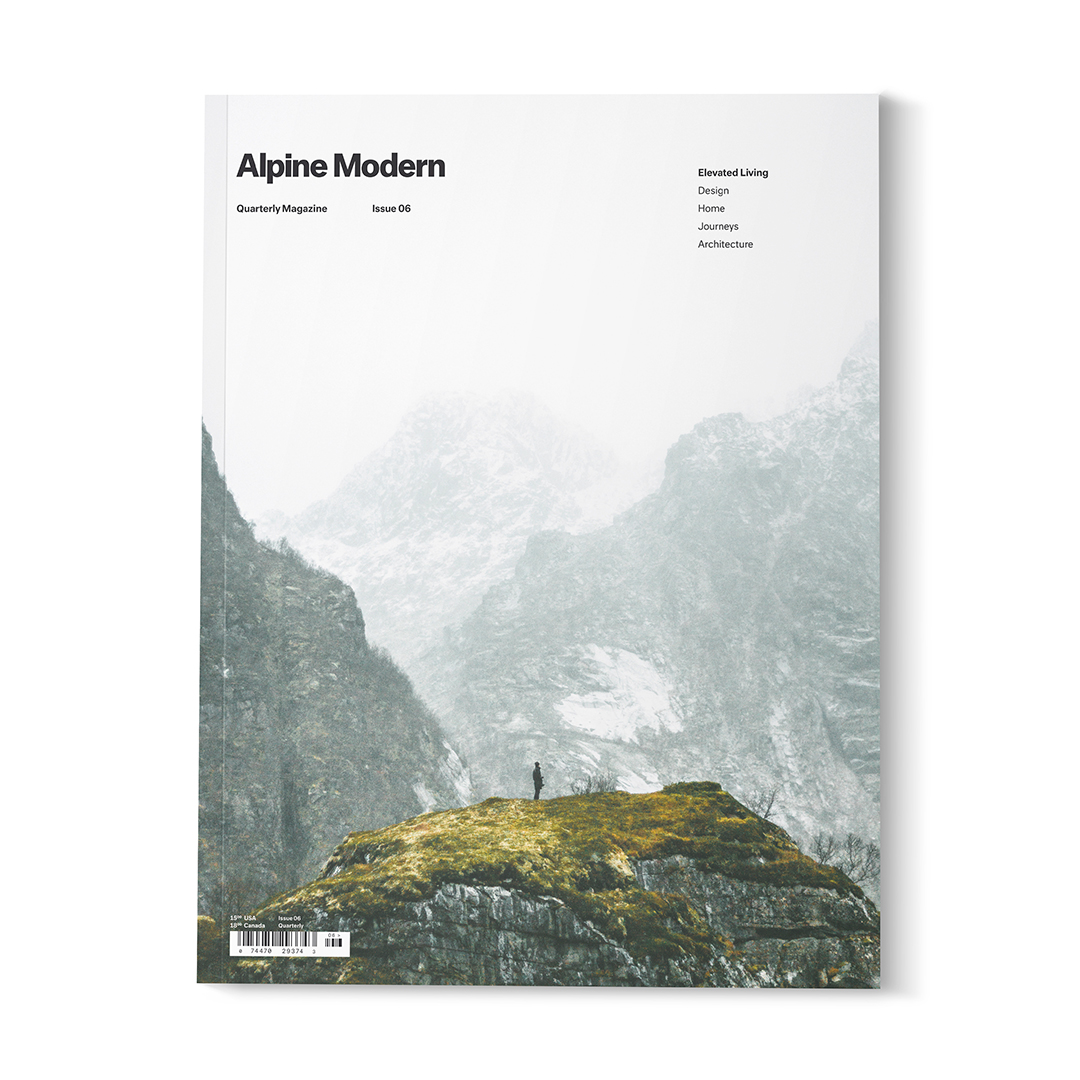

There is an image on the farewell cover of Alpine Modern’s print magazine. It is an image that fades from a near-white mountain backdrop to a dark silhouette of a lone person in profile standing on a mossy green capped rock. I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure. △

"I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure."

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently writing her book "Under the Influence of Architecture."

The Woolly Wonderland of Donna Wilson

A conversation with the London-based creator of cashmere creatures and other wild things.

Donna Wilson's imagination runs wild. In her studio in East London, the textile and product designer, who has been named "Designer of the Year" at Elle Decoration’s British Design Awards, creates cuddly cashmere creatures and designer objects from richly textured sofas and plush cushions to hip-cute bowls and plates to the planet's most darling socks.

The artist and craftswoman's continuous outpour of creativity began very early in her life, on her parents’ farm in the beautiful countryside of Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Encouraged and inspired by her grandmother, young Donna soon found her happy place in an old hen-house that became a cabin of crafts.

Her unbounded passion for making things with her hands and her love for art and design impelled Wilson to attend the Royal College of Art in London. It was there she knitted her first creatures and began selling them to local shops in the city.

These days, she greatly enjoys turning a 1860 cottage into a home for her little boys, Eli and Logie, and her partner, Jon. And she is busy designing a new collection of woolly woodland creatures, furniture, homewares, clothing, and so many more designer goods she now sells all over the world, with help from her team of craftspeople.

A conversation with Donna Wilson

What is your vision for your brand?

To create a wooly wonderland where patterns and color collide and imagination is free to run wild. It’s important to me that people can relate to the creatures and products, and that they evoke emotion — maybe a feeling of nostalgia, sentimentality, or happiness. Even if they just induce a smile, I feel I have done my job.

Where did the inspiration for your woolly wonderland come from?

I grew up on a farm, so I'm very familiar with natural landscapes. In my work, I find it very exciting to be able to replicate textures found in nature using wool and to try to mimic textures like moss, bark, and stone. It still amazes me that you can create a fabric from a bit of yarn.

"I find it very exciting to be able to replicate textures found in nature using wool and to try to mimic textures like moss, bark and stone."

My inspirations do come from all over the place — the landscape, music, dreams, magazines, ceramics, people, Scandinavian design. Sometimes, I just see a tiny snippet of something, which triggers an idea that is then developed into a product.

How would you describe your design style?

I try not to look at trends too much and try to keep focused on creating original designs that are distinctively colorful, graphic, and figurative, with a nod to traditional crafts and a pinch of whimsy.

What does quiet design mean to you?

It’s a reaction to the bombardment of images, products, and design we see on social media. Quiet design is more of a classic, true, folksy take on design.

What is your legacy (for now)?

It’s very important to me to promote local manufacturing and to help keep British craftsmanship alive. There’s too much disposability in products and consumer goods nowadays, and it’s environmentally irresponsible. I believe that if you have something that is handmade and is somehow more special than something made carelessly or mass-produced, you’re more likely to keep it for years, instead of throwing it away. I want to make things that people use, keep, and treasure for years.

"It’s very important to me to promote local manufacturing and to help keep British craftsmanship alive."

"I want to make things that people use, keep, and treasure for years."

What’s your favorite place in the world?

A few years ago, I was invited to design some furniture and wallpaper for a boutique inn that was being build on Fogo Island, off the coast of Newfoundland. We went as a small group of designers and stayed in an original Fogo Island house together. It was winter, and the snow was so deep it covered the cars. We drank gin-and-tonics with ice from 10,000 year old icebergs! We saw caribou and took a skidoo to remote places. The whole experience has really stuck with me and inspired my work.

"We drank gin-and-tonics with ice from 10,000 year old icebergs! We saw caribou and took a skidoo to remote places. The whole experience has really stuck with me and inspired my work."

Describe your dream home...

Amazingly, we live in a detached cottage with gardens and allotments surrounding it, which is pretty rare in London. It's an old building, built in 1860, and we are taking out time getting it the way we want, gradually. I'm really enjoying making this house our home. It's a lovely little house.

What does “home” mean to you?

Home is a place to have fun, make memories, play, make things, and relax. We have recently moved into our new house, so I am so aware of how much my home means to me, now more than ever. As I am finding places for my belongings, it feels like it is becoming our home more and more. A person’s home is so unique to them. We shouldn’t be afraid to express ourselves through our own decor and style. It might not be as obvious as what we wear — it’s more of a personal thing, and only our close friends get to see our homes.

"We shouldn’t be afraid to express ourselves through our own decor and style."

What’s more important to you in life?

My boys. Before having children, I could never have imagined how much these little people would mean to me. It has changed everything, and strangely, I am less stressed than I used to be. I think, I put things in proportion in life.

When are you happiest?

When I’m being creative. There’s noting better than having a day just to play, make, design, and produce lots of ideas, then finally you get something you like. It’s the best feeling in the world.

"There’s noting better than having a day just to play, make, design, and produce lots of ideas, then finally you get something you like. It’s the best feeling in the world."

Who is your design icon?

I like Alexander Girard, Stig Lindberg... and my grandma! Another designer I admire is Hella Jongerius. I love the sofa she did for Vitra a long time ago, with odd buttons. I’d never seen anything like this, and I love the way she uses textiles and color a lot in her work. Her designs are clever and thoughtful and have that human element.

Who inspired you to be the person you are?

My grandmother. She encouraged me to be creative and work with my hands, She was always trying to teach me things, like how to knit and crochet. I started being creative at quite a young age. I was always drawing and making things and was always happiest with a pencil in my hand. As a child, I didn’t know what I wanted to be when I grow up, but I knew it was going to be something to do with art and design. Now that I’m a mother, I’m inspired to encourage creativity in my kids and love seeing them getting all messy and using their imaginations.

"I started being creative at quite a young age. I was always drawing and making things and was always happiest with a pencil in my hand."

What is your life philosophy?

Do what you love and love what you do.

What are you working on right now?

We are working on the new collection for spring and summer 2017. We’re developing some new designs for ceramics and glassware. We are just about to launch our autumn/winter collection at the trade shows this month. I’m really happy with it, and there are lots of fresh, new products, like odd cashmere creatures and bamboo fiber picnic ware. We also have some special creative projects in the pipeline. △

More from Donna Wilson's collection:

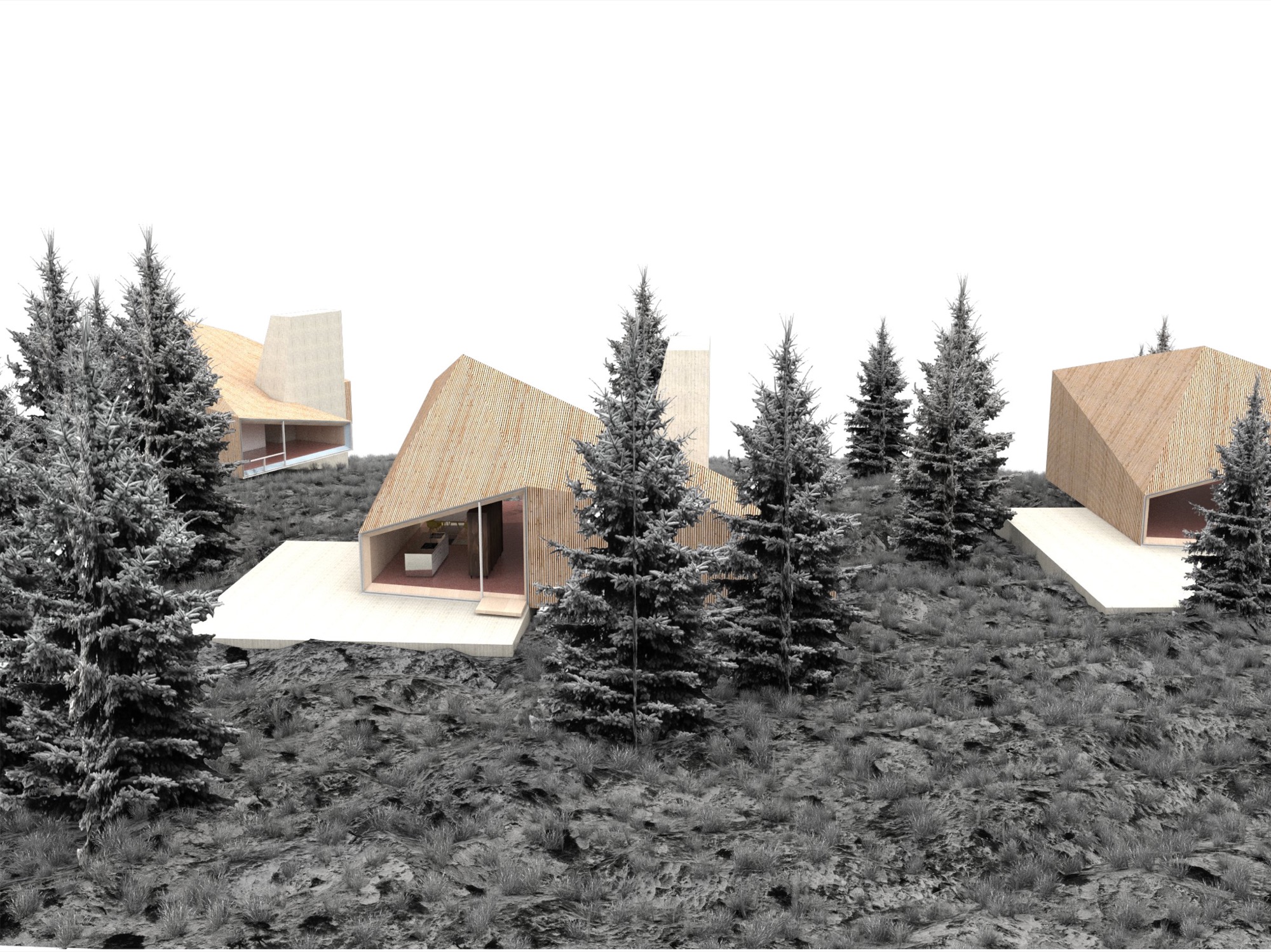

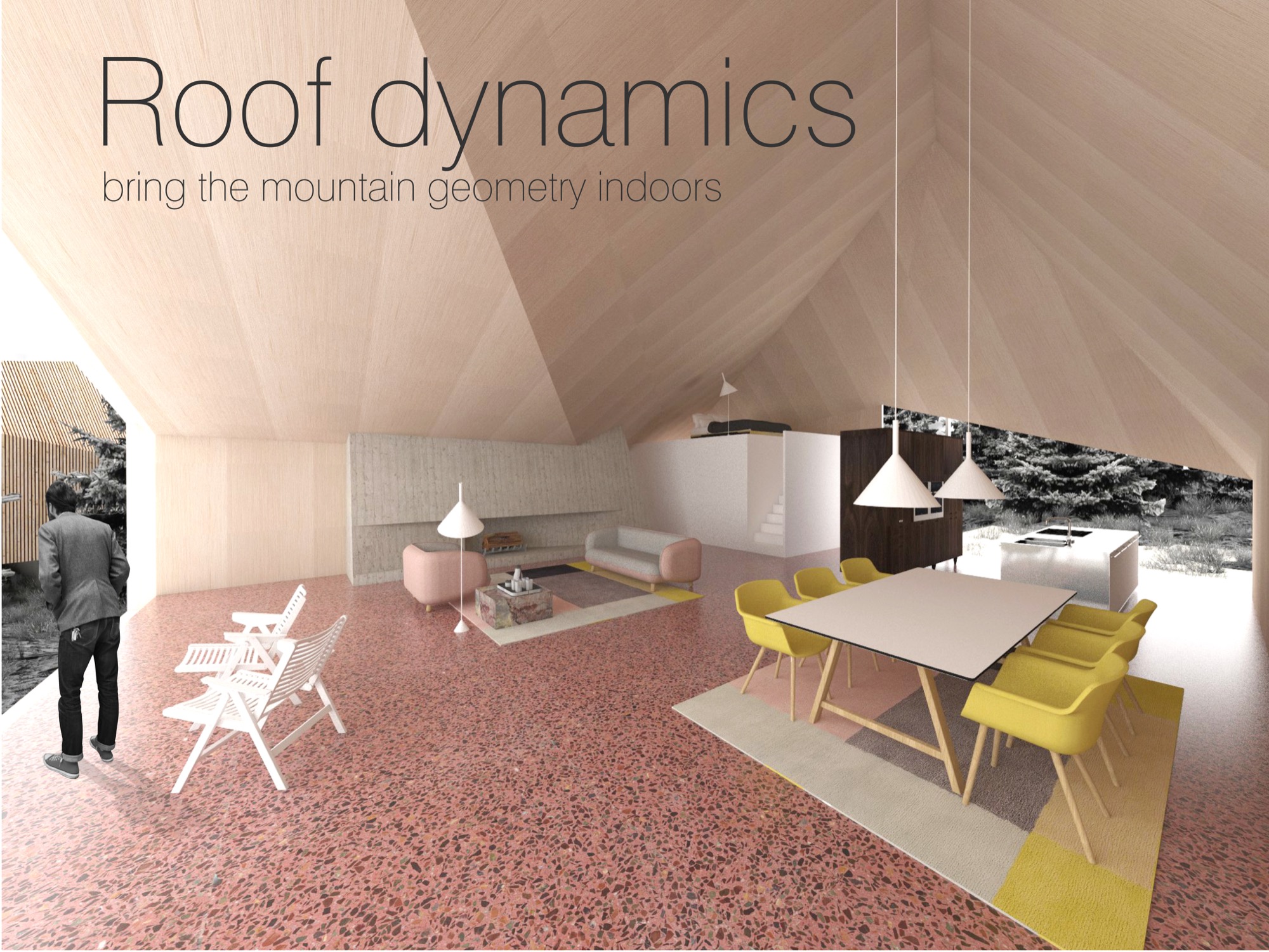

The Adventure House

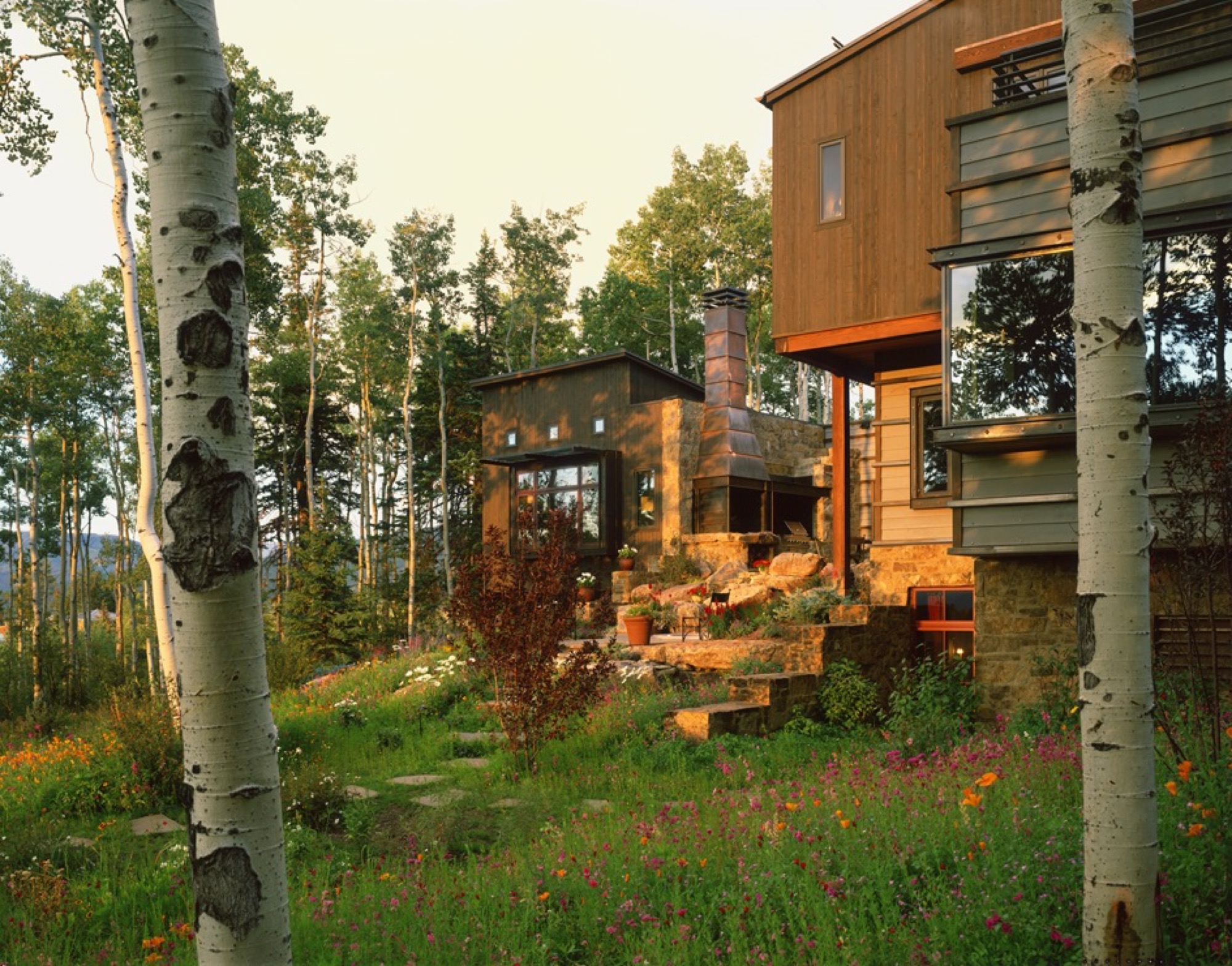

Seattle’s Olson Kundig creates an extraordinary family outpost with views of the North Cascades

Like wagons circling a campfire, a home that consists of sleek, airy pavilions embodies the concept of gathering.

When it comes to second homes, adventure makes the heart grow fonder. At least that’s the premise—and the promise—upon which Tom Kundig, of Seattle-based Olson Kundig, based his design for the staggeringly beautiful Studhorse residence in Washington’s remote Methow Valley. “Second homes are about adventure, and they are the homes that leave the most indelible memories,” Kundig says. “The best way to do that is to make them unconventional.” And that’s when things get interesting. Because when an architect of Kundig’s caliber decides to steer design in an unconventional direction, all manner of daring surprises can occur.

These days, Tom Kundig is a much-heralded, multi-award-winning architect (fifty and counting from the American Institute of Architects alone) engaged in projects spanning the globe. Yet, despite his growing international artistic stature, Kundig’s inspiration remains rooted in the profound experiences of his mountain-climbing youth. “I can tell you from experience that while mountain climbing may seem romantic, it’s also uncomfortable and scary,” he confesses. “You’re cold, hot, and sore. Why would anyone do it, if they thought about it logically? But it’s about engaging life vigorously. So is all of my best work.”

“While mountain climbing may seem romantic, it’s also uncomfortable and scary. You’re cold, hot, and sore. Why would anyone do it, if they thought about it logically? But it’s about engaging life vigorously. So is all of my best work.”

One fearless family

Fortunately, the clients who invited Kundig to design a mountain getaway for their young family on the edge of the North Cascades a few hours north-east of Seattle had a bold spirit and zest for adventure themselves. In fact, sharing adventures was part of their deliberate and mindful approach to building family memories. So it made sense that a rural retreat from their city routines would provide plenty of opportunity for outside-the-box living.

Truly life-enriching adventures are awakened by extraordinary locations, and this home’s setting is spectacular—twenty sagebrush-and-wildflower-strewn acres of rolling terrain unfurling beside Studhorse Ridge and overlooking the towering North Cascades and a lush stretch of the Methow Valley and Pearrygin Lake. It’s a quiet and peaceful perch with 360-degree views of wild Washington beauty.

Not surprisingly, the homeowners intended to spend as much time as possible outdoors, and that suited Kundig just fine. “Many of my buildings, even the public ones, involve being exposed to the elements in some way,” he notes. “And sometimes, there is even an element of risk, or daring, which is desired on the client’s part and intentional on my part.” So this home was designed expressly to provide plenty of access to fresh-air freedom. “The clients wanted a central space where the family and guests could come together in the landscape,” Kundig recalls. “We came up with the concept of the house feeling like a vintage motel with a series of buildings around a courtyard. From there, the conversation evolved into the idea of exploring the tradition of circling wagons around a campfire.” This engaging idea became the seed from which the entire home grew.

One big boulder

But first they had to deal with a rather large rock. “The site was actually completely empty when we began,” Kundig explains. “Except for the boulder that was positioned in what is now the courtyard area. It is a glacial erratic—a rock that a glacier drops as it recedes—and it was a driving element of the house composition, becoming the center point for the project.” So, in a gesture both timeless and eloquent, the home’s structural elements—and, by extension, the family’s activities—congregate around a literal and figurative touchstone. “I envisioned it as a large piece of furniture,” Kundig admits. Whatever you care to call it, the rock has become a much-loved feature of the home. “We loan the house to friends a lot, and we leave a Polaroid camera next to the guestbook,” says the homeowner. “That book probably has a hundred pictures taped inside by now, and I bet ninety of them show people on the rock. People see it and they say, ‘That’s amazing you put this rock here,’ but we say no, we built the house around the rock!”

An elegant assemblage

The home comprises a series of buildings clustered around a central courtyard. Viewed collectively from a distance, the constellation of structures has the striking presence of sculpture artfully arranged in a landscape, but each element is also simply practical. Each structure/pavilion has a defined purpose, and taken together they fulfill all of the family’s requirements, so residents and guests circulate among and between the buildings in daily paths dictated by their activities. The main structure is nearly entirely encased in glass. (Kundig calls it “lantern-like.”) Anchored by a massive concrete fireplace on one end, with a living room, dining area, kitchen, pantry, bar and bath—this is the main indoor gathering space. Another structure just beside it contains private family bedrooms upstairs and a guest bedroom and shared den below. Across the courtyard, a third structure offers space for the garage, storage and laundry facilities, and connects through a breezeway to an extra guest suite. The fourth and smallest building, set slightly apart and in a meadow, houses the sauna.

The structures were meticulously positioned to precisely frame gorgeous mountain and valley views, and the negative space (the open space between buildings) they create was considered with the utmost care. When vistas are framed from different angles, we perceive them in new ways, Project Manager Mark Olthoff explains, and this home’s design repeatedly plays with the idea of varying points of view. Olthoff notes that the moment of arrival is a particularly significant experience, so in this case it was important that the view greeting one’s eyes upon entering the complex from the parking area be pristine. Dazzling glimpses of landscape are framed cleanly by the built structures, with no overlapping edges of rooflines to mar the dramatic impact of the first impression.

Kundig explains that the strategic arrangement of the structures, which he refers to as “lean, geometric pavilions of steel, barn wood and glass,” also puts their extended rooflines to work—providing shade and natural cooling in the heat of summer and creating a covered passageway when rain and snow fall. The central courtyard, swimming and play zone become a natural focal point at the heart of the cluster of buildings, practical for a busy family with energetic children, ideal for entertaining a group of guests, and perfectly charming as an impromptu dance floor.

Simple and solid

Yet, while the home is certainly gracious, it is far from grand. “We relied on everyday building materials when possible and used the common materials in uncommon ways, such as exposed plywood for flooring or walls,” Kundig explains. “The materials—mostly steel, glass, concrete and reclaimed wood—were chosen for their resilience against the scorching summer sun and freezing, windy winters that define the region. The materials are expected to weather over time with their surroundings, and to blend in.” If the wood siding shows quirks of character and age, then that’s because it was salvaged from an old barn in Spokane, Washington. And plywood is more practical than precious. “The ceilings are ACX plywood,” Kundig says. “The rest (cabinets, floor, and walls) is AB marine-grade plywood, which we used because the edges would be exposed and marine grade has tighter laminations and holds an edge better.” With a gray-toned stain, the humble boards take on a refined appearance belying their usual orange-tinged reputation. For her part, the homeowner is delighted with the home’s unfussy durability and general livability. “It’s made to stand up to the occupants,” she says admiringly, noting that the family retreat is “worked hard.”

“We relied on everyday building materials when possible and used the common materials in uncommon ways.”

Four-season comfort is assured, thanks to a series of astute climate considerations. A geothermal heating system (with electrical backup) warms the home and its concrete floors. Air conditioning is unnecessary, given the home’s elevated location, which allows breezes to filter through the rooms. And giant, industrial-sized fans in the living room and bedrooms keep the air circulating. Moreover, many of the walls and windows were designed not merely to open but to essentially disappear, blurring interior-exterior boundaries as the home and its landscape intermingle.

Kinetic elements

And here’s where some of the home’s adventurous personality really comes out to play. Kundig has developed a reputation for buildings that incorporate kinetic elements (Olson Kundig even boasts an in-house “gizmologist”), and this house is no exception. Moving parts are built into the fabric of the home, adding a functional—and undeniably fun—versatility to the spaces. The main pavilion’s floor-to-ceiling windows and giant Fleetwood sliding doors enable the expansive room to completely open to the great outdoors. Nearby, the indoor bar converts to an al fresco watering hole when the steel-and-wood back wall flips open on hydraulic pistons. (Kundig likens the experience to Coney Island.) And in a bravura demonstration of crowd-pleasing cleverness, one entire reclaimed-wood-clad den wall is designed to swivel ninety degrees outwards, so that the big-screen television becomes an outdoor movie screen, and the courtyard—and a perfectly placed semi-circle of landscaped rock seating—becomes an open-air cinema.

[video width="640" height="360" mp4="http://www.alpinemodern.com/editorial/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/400983501.mp4" loop="true" autoplay="true"][/video]

Scandinavian style meets the mountain West

Debbie Kennedy, an interior designer with Olson Kundig, helped guide the creation and selection of furnishings and finishes for the home. “We wanted to stick to a very simple unpretentious palette of materials—materials that feel like they belong in the landscape and the interior,” she says. “Limiting the number of materials helps the spaces flow into one another.” Concrete, steel and reclaimed wood are major players both indoors and outdoors. “The clients are very drawn to Scandinavian design—both contemporary and vintage,” Kennedy explains. “In this instance, the goal was also to incorporate modern refined Western mountain references.” Kundig notes, “The focus was on beautiful yet practical pieces that would age as well as the buildings and, similarly, relate to the region and mountain landscape.”

The homeowners preferred a casual look and a welcoming feel, with occasional bright splashes. “The dining chairs presented a great opportunity to introduce a pop of color,” Kennedy notes. “And the client fell in love with a vintage-blanket chair by Maresa Patterson, so we asked her to work with us on a pair of chairs.” Kundig adds, “A few key pieces—such as the dining table, coffee table, fireplace screen, and built-in beds—were custom-designed by the team.” Kennedy singles out one example: “The folded steel console is from the Tom Kundig Collection and feels like it was ‘meant’ for the house.”

Defying easy categorization, the Studhorse residence is emphatically individual and entirely unforgettable. Perched on a prospect overlooking a breathtaking panorama, the clustered elements of the home manage to both embrace and enhance its incredible surroundings. As a hummingbird flits straight through the open walls of the living room and into the kitchen on a sunny spring afternoon, the allure of Tom Kundig’s vision is clear and complete. As he explains, “Architecture allowed me to have a foot in both places—the technical realm and the poetic realm—and in that magical intersection between the two.” △

“Architecture allowed me to have a foot in both places—the technical realm and the poetic realm—and in that magical intersection between the two.”

The Fragrance of "Out There"

A harvest walk on the wild side with the wilderness perfume crafters of Juniper Ridge

Hall Newbegin is out there. Upon first meeting him, I didn’t expect it. He seemed jovial, unintimidating, and mild-mannered. But in the first five minutes of our conversation he used the phrase “out there” eight times — “Part of what I wanted to do was to just be ‘out there’ . . . Being ‘out there’ just centered me . . . Being ‘out there’ saved me as person . . . I had no idea where this was going, but I loved being ‘out there.’ ”

Return to the wilderness

All of us go through periods of discovery in our lives when we are searching for direction, trying to find out what defines us and how it can drive our life and work. For Newbegin, the founder and head perfumer for Bay Area-based Juniper Ridge, that discovery came after a stint on the East Coast and a return to his roots in the West, a return to the wilderness — “out there” — where he feels most comfortable and alive.

Newbegin never imagined that being “out there” would lead to a burgeoning fragrance business, with his products sold in outlets around the globe. He stumbled upon the idea after trial and error — in his life, in his passions, and in his own business.

Capturing the essence of being “out there” is the driving force for the people who run Juniper Ridge, which proclaims itself the world’s only wilderness fragrance company. Headed by Newbegin and the firm’s chief storyteller and packaging designer, Obi Kaufmann, Juniper Ridge, per its website, is “built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

“Built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

Newbegin and his team embrace this mantra through a process called wild harvesting, where they make real fragrances from the places they know and love — the trails of the rugged and diverse American West.

Their teams of hikers crawl through mountain meadows, smelling the earth, the wild flowers in bloom, or the moss covering the trees, then harvest the ingredients to capture the real scent of that land. Armed with public permits or private permissions, they gather wild flowers, plants, bark, moss, mushrooms, and tree trimmings, then distill and extract fragrance by employing ancient perfume-making techniques of distillation, tincturing, infusion, and enfleurage. These formulations vary yearly and by harvest, due to rainfall, temperature, specific location, and season.

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive.”

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive,” says Newbegin, whose Instagram handle is @crawlonwetdirt. Yet this call to the primitive is based in fact: Our sense of smell is often called the oldest sense, the only one with a direct connection to the brain. That connection brings pleasure and sparks memory, transporting us in time and place. For the team at Juniper Ridge, the time and place is marked on every bottle of fragrance they sell. In fact, they authenticate the process of each harvest by stamping each package with a harvest number and by documenting the process through an accompanying story and photographs on the Juniper Ridge website.

“Our muse is the place. And our job is to funnel that the best we can,” says Newbegin, pointing to a small spray bottle of Sierra Granite, a fragrance connected to California’s Sierra Nevada. “Everything in this bottle is real. Our test is always ‘Is it the real place?’ ” Some of the other places they have captured include Big Sur (California coast), Siskiyou (Oregon coast), Mojave (Mojave Desert), and Cascade Glacier (Oregon’s Mount Hood).

“Our muse is the place."

Real fragrance resonates

Kaufman notes that as the business has grown, sales have been strongest in Scandinavia and New York City. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, it takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us,” he says. “Ninety-nine percent of the people who buy this have never been to the Mojave Desert, but because it’s real fragrance, it resonates — this is real, it’s not Comme des Garçons, it’s not that bullshit stuff at the Nordstrom’s counter that’s made from petroleum, and that never existed on earth until ten seconds ago. Because this is real, it goes deep into our genetic past — we’re responding to something real.”

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, [the fragrance] takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us.”

Saved by the wild

While hiking on Marin County’s Mount Tamalpais with the sometimes loquacious but unassuming Newbegin in his worn T-shirt and jeans, it’s hard to imagine that he would describe the transcendent moment of his life as a cliché. But those are the exact words he uses when he muses on the importance of the wilderness and the outdoors: “I feel like it saved my life.”

Growing up in Oregon, with Mount Hood in his backyard, Newbegin spent most of his youth hiking and backpacking. He attended college in New York but knew there was something growing inside of him, “a hunger to get back to the West and be in the mountains . . . I had camping and being outdoors in my blood. It’s a deep West Coast/western cultural thing,” he says.

With a last name like Newbegin, it seemed inevitable that he would eventually find his true calling. That happened in Berkeley, California, after a period he deems his “hippy schooling.” He took inspiration from eco-wilderness writers including Gary Snyder, John Muir, and David Brower and studied under commercial mushroom harvesters, members of native plant societies, and herbal medicine teachers.

New beginning

The real turning point came as he was foraging native medicinal plants in the Sierra Nevada. “I dug my trowel into osha root, and the air just exploded with that smell and it’s like, ‘ahhh.’ It would just slay me,” he says. “I didn’t know what the stuff was. I wasn’t thinking about fragrance or anything. I just loved being out there. It just centered me. It brought me into this world where the big thing is there, and it just brought peace over me. You’re looking at plants, at trees, your map, and you smell the ground and suddenly it breaks. You’re just there. All that chatting in your brain just stops, and you’re just there.”

This was the beginning of an epiphany, but the path from being an outdoorsman to becoming a true perfumer has been sixteen years in the making. “You know how journeys are,” Newbegin says, “You just start taking your steps, and soon you start getting somewhere. And so, I started learning how to extract goo out of plants. I was going to the Berkeley Public Library and trying to figure out the old extraction techniques of how you get the goo out of the plants.”

Eventually, he was mixing that goo with other ingredients to make soap and selling it for four bucks a bar at the Berkeley Farmers’ Market. He describes encounters with his first customers: “They would say, ‘Oh my God, this is Big Sur in a soap.’ ” Sounding a bit like Hemingway, he would give them the authentic story of the day that it was harvested — “I got black sage goo on my arms, and I took a nap under this big black sage shrub and had dreams about it and woke up, and the sun was on my face, and the air was just filled with the cleanness of black sage and bees in the air.” Their response, according to Newbegin: “OK, I’ll take ten of those, right now.”

Goo business

After quickly selling out of his product, Newbegin also realized that he was vastly underpricing his offerings. Over the years, he and his team have refined not only the process to get very consistent quality, they have also learned how to price their product to create a sustainable business. Newbegin laughs when he says, “We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.” And yet, it is a business that is working — with retailers such as Barneys New York now carrying the product, and outlets as far away as Paris, Moscow, and Tokyo.

“We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.”

And Newbegin’s enthusiasm for his product and the process is still very evident. “When I hand this to someone, I think to myself, ‘Oh, my God, you’re getting something just unbelievable.’ All that green in there . . . This is what Mount Hood was like as of September fourth of last year. All that green goo, tree pitch. It’s just real. It’s just 100 percent real.”

The Juniper Ridge team talks about how this realness is a stark contrast to the more synthetic nature of traditional perfumes. Those classic perfume houses employ someone who is called “a nose” to help them create unique fragrances. Globally, there are around fifty “noses” who are highly sought after for their olfactory abilities.

Although this is rarefied air that Newbegin wants no part of, he does refer to himself as “the Pied Piper of the nose.” He is quick to recall the power of the sense of smell. “My message is, use this primitive thing because it will change the person you are.” The scent of nature “is everywhere, all the time. So wake up your sense of smell,” he exhorts. “I want people to do it, not because they should, but because it’s the most sensually gratifying thing they can experience. It’s wonderful.”

Try for yourself

Newbegin’s final piece of advice: “Do what we do — get outdoors, crawl around on your hands and knees, smell the wet earth beneath your feet. Or if you’re worried about embarrassing yourself (which you should be since people don’t normally crawl around on trails), just start by crushing tree needles and plants under your nose. Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.” △

"Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.”

Concrete Perspectives

Australian photographer Jake Weisz discovers the minimalist Amangiri Resort in Southern Utah

Through his lense and all his senses, Australian photographer Jake Weisz (@jakeling) experiences the calm luxe and the raw surrounding nature of Southern Utah’s Amangiri Resort, where minimalist architecture in monochromatic concrete lies below the buttes and mesas of Canyon Point.

After an unforgettable, slow drive along a private, paved road between colossal ridges and across vast landscapes, we arrived at what I can only describe as a concrete castle hiding in the rocks of Southern Utah. Amangiri was and remains the greatest architectural experience of my life as a photographer. Minimalism, texture, silhouette... all unassuming until I wandered through this artistic haven of concrete walls.

A collaborative design by architects Rick Joy (Tucson, Arizona), Marwan Al-Sayed (Hollywood, California) and Wendell Burnette (Phoenix, Arizona), Amangiri spreads over 600 acres (243 hectares), with 34 suites and a four-bedroom mesa home, a lounge, several swimming pools, spa, fitness center and a central pavilion that includes a library, art gallery, and both private and public dining areas. The architects were commissioned by legendary hotelier Adrian Zecha, whose Aman Resorts have redefined luxury travel in epic proportions.

Arriving at the resort

We wandered across the dramatic entrance, past the protruding canyon on the right and stepped into the first breezeway, one of numerous voluminous concrete corridors that connect each pavilion to the next, framing the valleys in the distance and creating different moments of awe every time you step inside. Throughout the day, the sun hits each breezeway at different angles, giving light and shadow new meaning, in a continuous cycle from dawn until dusk. Impressions of grandeur aside, with each stride deeper into these grand hallways, I felt closer to sublime serenity; this indescribable feeling of peace.

We were shown to our room, a one-bedroom suite on the edge of the property, backing to what at first glance reminded me of a set built for a spaghetti Western: rolling tumbleweeds, the squeaks of desert mice, expeditious hares scurrying about, the scene set against luminous canyons and a distant view of Broken Arrow Cave, an indigenous, spiritual sanctuary. Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.

“Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.”

Exploring perspectives

After some rest in our noble lodgings, the photographer in me yearned to roam the grounds, Canon in hand, and to capture the tranquil austerity surrounding us. Being here, each of the architects’ decisions made sense. Moments of monotony broken by jagged slices of deep, sweeping pastel views. The polished concrete’s organic texture caressed by soft waterfalls cascading down the walls. Brief Edenic allusions in fruitful apple trees, ripe for the picking. To grasp we were only a couple hours’ drive from Las Vegas, Nevada, was almost impossible.

Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls. Rather than being clinical or cold, as unknowing observers might reckon from afar, the stark concrete structure’s monochromatic elegance creates harmonious balance between the arid landscape in a desolate summer climate and shadowed walkways affording gentle breezes of desert wind.

“Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls.”

Fortress of luxe

Stepping inside Amangiri superseded any notions I had of comfort and luxe. The main pavilion is a multipurpose common area scented by burning fresh sage and sunburned grain. On the walls, copious Ulrike Arnold artworks implement abstraction from the concrete’s silky texture. The interior seamlessly merges textures as if designed by rhythmic dictation. Soft leathers and animal hides, smooth oak and cement surfaces all amalgamate with the rough, rambling terrain that surrounds the resort.

I experienced color in this place like never before—the perfectly blended gradient changes from earth tones to milky hues. The architects of Amangiri also designed all interior features; furnishings, lighting, signage… all the elements reflect the Southwestern landscape and culture with subtle, emblematic references to the Native American tribes that once inhabited Canyon Point.

Dining at dusk

The Amangiri invited us to take our first meal alfresco in the Desert Lounge, a rather humbling setting for our dinner at dusk. Sitting across from my friend, charging our glasses of wine and looking out at the immense horizon, overcome with divine silence and calm, we couldn’t speak but simply look and listen. Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food. Amangiri presents a rather auspicious combination of locally sourced, farm-fresh produce and materials with modern interpretations of Southwestern traditions. Plate for plate, the decadent courses filled us, until we turned in for the night. First day, well spent.

“Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food.”

An early adventure

From the crack of dawn, Amangiri had been already awake and buzzing. We were informed to wear shoes suitable for an adventure and were later met by a car. Amangiri sits among some of the continent’s most grandiose, well-protected natural phenomena, and we were booked to experience one the resort is very proud to have on its land. At the foot of the largest of the canyons, they put us in climbing harnesses before we set off on a Via Ferrata, Italian for “Iron road.” This modern style of climbing journey involved steel cables and staples already in place for a more protected climb. The concept is to give inexperienced climbers the ability to enjoy rather dramatic and difficult peaks. And now, with my feet firmly back on the ground, I can say, the peak was indeed spectacular. Nerves aside, climbing to the top allowed me to truly experience the vastness of this beautiful place and the fragility of this natural ecosystem. I do, however, recommend taking an extra few breaths before crossing Amangiri’s signature suspension bridge between two peaks. Walking across with my camera was a rather nerve-racking experience.

After that intense climb and exploring more of the resort’s outdoor adventures, the best decision was to spend our afternoon at the Amangiri Spa. The minimalist design of this serene adults-only oasis manifested the very concepts of relief. Instead of receiving a massage treatment, I spent most of my time self-reflecting in the floating cave’s Persian salt pool. 30 minutes of pure and simple bliss, resting on the surface of tepid water, scored by meditation melodies has become my new idea of elegant content.

Departing to return

Our departure was suitingly emblematic of our entire experience at Amangiri. As we unhurriedly drove past the minimalist concrete marvel, through the resort’s expansive acreage and past a private plane landing nearby, I began to appreciate the sheer magnitude of my weeklong stay here. The space has inspired a newfound understanding of lines and light, and a greater comprehension of the relationship between nature and man-made creations. As I left, I already longed to return. △

Dwell × Alpine Modern

We are incredibly excited to announce our partnership with Dwell

From the very beginning, as we imagined Alpine Modern to be a publication about modern architecture, design and elevated living in the mountains around the world, telling people about our vision has usually included something like "You know, like if Dwell and Cereal magazine had a lovechild in the mountains..." Dwell's authority in showcasing international modern architecture and design has inspired us in our own work. This is why we are incredibly proud to announce that today marks the beginning of our partnership with Dwell.

This means, you will see some of our editorial stories on the new (launched today!) Dwell.com, published under the banner of Alpine Modern. What's more, we will present Alpine Modern "Curations" — a new element of the redesigned Dwell.com. This can be anything from a product roundup from the Alpine Modern Shop to a themed collection of stories about cabins, art and journeys in Norway.

In return, you will read cherry-picked Dwell content on Alpine Modern Editorial.

Follow @alpine_modern along on Dwell.com as Dwell and Alpine Modern together kindle a longing for elevated living, through slow storytelling, amazing photography and tightly curated alpine-modern objects. △

The Creator of Whimsy

Danish architect and designer Hans Bølling talks with us about his iconic wooden figures, modern design and his wife and muse, Søs

Danish designer Hans Bølling is best known for his iconic humorous wooden creatures. His modern-design legend began when, early in his career, the trained advertising designer playfully crafted small figures as gifts for his beloved wife.

Thanks to the precision and personality in Bølling's objects, he quickly began selling the wooden creatures to stores. Soon thereafter, he won a design award and invested the winnings in his own carpentry machine. A fortuitous acquisition, as it kickstarted the production of Bølling's now-iconic Duck and Duckling in the 1950s. The rest is modern design history.

Bølling's classic Duck and Duckling and their wooden friends, which include Strit and the Optimist and Pessimist, are still being produced by the Danish company Architectmade.

Born 1931 in Brabrand, Denmark, Bølling now lives in Charlottenlund with his wife Søs, whose father, he tells us, is responsible for his branching out into architecture. Balling eventually graduated as an architect from The Royal Danish Art Academy.

We caught up with the prolific Dane only a few days after his 85th birthday. Astonishingly, Bølling, who says he's too busy working and having fun to retire, is still creating many more new objects in his atelier.

A conversation with Hans Bølling

Tell us about your remarkable journey from architect to product designer.

It all starts with Søs, my wife. We met when she was 16-and-a-half, and I was 21. I was going to be an advertising designer, but her father didn’t think I would be able to support her with that kind of job. So I graduated from The Royal Danish Art Academy and became an architect.

I started working in her father's design office in the very center of Copenhagen, just by Læderstrædet, Højbroplads and Amagertorv. Since then, I have been working in different places and have created a vast variety of works, ranging from town halls and living complexes to villas, furniture and wooden figures.

Actually, the wooden figures came before everything else. It was something I couldn’t help doing. I created all of them for Søs. In the beginning, I would make them out of coconut tree, Brazil nuts, bog oak and whatever material I could find. At some point, I won a competition creating a pattern that everyone thought was made by the famous Danish ceramic artist Axel Salto. I won some money and bought myself a turning lathe. This became the starting point for the figures you know today. The turning lathe inspired me to do the Duck and Duckling, Strit, Oscar, the Mermaid, the Optimist and Pessimist, and so forth.

What’s the story behind your wooden figures, why these whimsical little characters?

All of my wooden figures have been made for Søs. In that sense you can say that I built my career on love. In the beginning, I made the little Oscar out of Brazil nut. I have been making orchestras with figures playing the flute, drum, guitar. The Optimist and Pessimist were inspired by two colleagues of mine, were the one was always happy and smiling and the other was always moody and sad. For the Duck and Duckling, I was so fascinated by this story about a policeman who stopped the traffic to help a duck and her ducklings pass the street. A photographer caught it on camera, and the picture went around the world in 1959. After that amazing story, I felt inspired to create the Duck and Duckling on my turning lathe.

"All of my wooden figures have been made for Søs. In that sense you can say that I built my career on love."

What makes you a modernist at heart?

I don’t know. I have just always been doing modern things, modern buildings, modern furniture. I was influenced by Søs’ father, Axel Wanscher, her Uncle Ole Wanscher, and the whole scene they where part of.

What does “quiet design” mean to you?

I like classic and simple design, with a strong idea behind it.

What are you working on these days?