Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Recipe: White Asparagus and Morel Salad

A delicate side dish with morels poached in beurre monte

Ingredients

- 6 white asparagus

- 6 morels (cleaned)

- 2 radishes

- 1 bunch ramp tops

- 1 egg yolk

- 1 shallot

- 2 pounds (907 grams) butter (cubed)

- 1 tablespoon (15 milliliters) water (for beurre monte)

- 4 ounces (113.3 grams) Delice de Bourgogne cheese

- Dandelion greens

- Sheep sorrel

- Red orach

- Purslane

For the white asparagus

Trim away the woody ends and blanch the white asparagus in salted boiling water until cooked (three minutes). Transfer to an ice bath. Once cool, cut each piece into three small pieces (batons). Reserve for later.

For the ramp top puree

In a saute pan, add the diced shallot and one tablespoon (15 grams) of butter to hot pan. Sauté shallot until translucent. Add cleaned ramp tops and cook for five to seven minutes. Add cooked mixture to blender and puree on high for thirty seconds. Chill and reserve.

For the beurre monte

Add one tablespoon (15 milliliters) of water to saucier pot, heat, and slowly add the cubed butter. Whisk constantly until water and butter have emulsified. Season generously with salt and pepper. Reserve on a simmer.

For the egg yolk

Cook for one hour at 63.5º C (146º F) in a mixture of grapeseed and olive oil.

To Finish

Gently poach the cleaned morels in the beurre monte mixture for four

minutes. Wipe off any excess butter. Put on the plate.

Toss the white asparagus in a small amount of the warm beurre monte, and put on the plate.

Spoon the ramp top puree alongside the morels and white asparagus.

Place the Delice De Bourgogne on the plate.

Add warm egg yolk, sliced radish, dandelion greens, red orach, and purslane.

Recipe: Alpine Fizz

A gin cocktail with homemade huckleberry-sage syrup

Ingredients

- 1½ ounces (44 milliliters) CapRock Gin

- ½ ounce (15 milliliters) Braulio

- ½ ounce (15 milliliters) huckleberry-sage syrup *(see additional recipe)

- ¾ ounce (22 milliliters) lemon juice

- 1 egg white

Combine all ingredients in a shaker tin.

Dry shake ingredients without ice to aerate egg white.

Shake ingredients with ice to chill and dilute.

Using a hawthorne and a ne strainer, strain cocktail into a chilled coupe.

Garnish with fresh herbs and/or huckleberries.

For the huckleberry-sage syrup

Combine equal parts huckleberries and granulated sugar into a sauce pot.

Bring to a boil and simmer just until the huckleberries begin to burst.

Add sage leaves and continue to simmer gently.

Once infused, remove sage leaves and discard.

Place syrup into a blender and blend until smooth.

Strain syrup with a strainer and refrigerate until cool.

Final product should be thick but pourable, adjust with water if necessary.

Recipe: Smoked Trout Salad

Home-smoked fish alongside woodsy fiddlehead ferns

Ingredients

- 1 cup (236.5 grams) salt

- ⅓ cup (71 grams) sugar

- 8 ounces (227 grams) emmer wheat (farro)

- 1 lemon

- 1 bunch parsley

- Fresh cherry tomatoes

- Chives

- Sherry vinegar

- 8 fiddlehead ferns

- 6 ounces (170 grams) fresh cheese (burrata)

- Dandelion greens

- Chickweed

- Red ribbon sorrel

- Wild wood sorrel

- Yarrow

For the smoked trout

Combine one cup salt (236.5 grams) and one-third cup (71 grams) sugar and sprinkle evenly over the small filleted fish. Refrigerate for eight hours to cure. Remove from fridge and rinse under cold water. Refrigerate the fish overnight, uncovered. In the morning, light the charcoal grill (preferably using applewood and charcoal). Once the coals are hot, push them to one side of the grill. Place a tray with ice next to the coals. Put the grill grate on top of the charcoal and the tray of ice. Set the trout on a metal baking pan directly above the tray of ice and “smoke” the trout for ten minutes.

For the farro

Put the farro in a pot and fill with cold, salted water until the farro is submerged. Bring to a boil and simmer. Cook for fifteen minutes until the farro is tender. Strain. Season generously with lemon juice, sherry vinegar, salt, and pepper. Add sliced tomatoes, sliced chives, and parsley.

For the fiddlehead ferns

Remove the top portion of the stems and blanch in a large pot of salted, boiling water for a eight to ten minutes, until tender. Place in a small ice bath to stop the cooking process.

To finish

Spoon the nished farro onto the plate.

Add the smoked trout on top.

Garnish by adding the fresh farm cheese, seasoned fiddlehead ferns, dandelion greens, chickweed, sorrels, and yarrow.

Drizzle with Extra Virgin Olive Oil.

Alpine Modern Chef Colin Kirby on fiddlehead ferns:

The ingredients featured in these pages make all the difference. Wild, fresh, and foraged flavors have become a staple in the culinary world, and this dish reflects that point. A main component to the smoked trout dish is the fiddlehead fern. The ferns have a great woodsy, almost bitter flavor reminiscent of where they came from: the forest floor. Their texture is superb, providing an added bite to the creaminess of the trout and fresh cheese. Technically, they are the furled fronds of ferns. They are incredibly healthful as well, high in fatty acids. Fiddlehead ferns can also be pickled and eaten anytime.

Refuge in Concrete

Refugi Lieptgas is the negative imprint of its ancient predecessor

Using the decrepit log cabin as mold, Swiss architect Selina Walder sculpts a minimalist mountain retreat in concrete, fossilizing the texture and character of the historic hut that once stood in its sylvan spot on the meadow. From the trail, hikers may mistake Refugi Lieptgas for the inconspicuous log cabin that had stood in this very spot for decades. Yet, at second glance, the tiny refuge tucked against boulders at the edge of the Flims forest in the Swiss Canton of Graubünden reveals itself as the negative imprint of the old structure. The stunning effect of the cabin cast in concrete is incongruously sublime; details like the wood grain, the cracks, the door lock set in stone are all true impressions of the past.

Stonewalled Design

The Maiensäss mouldering on the mountain meadow had long served its purpose of sheltering pastoralists during grazing season. Years back, Guido Casty, the 1974 bobsledding FIBT World-Championship silver medalist and local restaurateur who owns the property, had planned to replace the crumbling herder’s hut with a new cabin he could rent out to vacationers. The building permit was denied. The new design needed to somehow incorporate the existing structure. He gave it a rest.

When his itch to tackle the old cabin returned, Casty tasked an architect friend in Basel with a new plan that would comply with the community’s stipulations. Since the project was small and the architect was two and a half hours away, Casty asked Selina Walder of the local Nickisch Sano Walder Architekten to manage the construction. The Flims native had been waitressing for him for many years and graduated from the renowned Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, where she had studied architecture under Valerio Olgiati, one of Switzerland’s foremost modern architects.

Walder agreed but didn’t like the design she was handed from the Basel architect. The twist: The building authorities had miscommunicated the structure’s prescribed maximum footprint. As a quasi apology, the local architect was allowed to rebuild from scratch, as long as her plan adhered to the original square footage, and the new design portrayed the character of the old log cabin.

What did that mean? “I struggled with that provision,” Walder admits. “Did I need to rebuild with wood?” She inquired further but was discouraged from asking too many questions that would only have to be addressed with more rules.

Walder’s reluctance to use wood lingered. “The spot was mossy, woodsy, musty,” she remembers. “You could tell the old log cabin hadn’t taken well to sitting on the forest floor.” Besides, the original had been constructed from surrounding trees. And today’s way of driving to the lumber yard and transporting the wood back to this unspoiled spot at the forest’s edge didn’t seem appropriate to her.

“The spot was mossy, woodsy, musty. You could tell the old log cabin hadn’t taken well to sitting on the forest floor.”

Serenity set in stone

Thus, the fossilization idea was born. “I did love the sylvan setting back in there, where the old cabin cowered against the boulders,” Walder says. “I wanted to preserve that, not fuss about a new design. I wanted everything to be the way it was. Except, I didn’t want to rebuild in wood.” Her answer was to cast a negative imprint of what once was, from concrete, to create a simple refuge that—now literally—mirrored the character of the derelict log cabin.

The young architect intended to capture this special place, the woods she had loved since childhood. “I wanted people staying at the cabin to understand the forest in all its beauty, all its fascination, all its facets.” In fall, for example, the new cabin's round skylight gives view to the vermillion crowns of the beech trees above. The main room’s large window is purposefully set low to provide an ideal view over the clearing when sitting at the table. “Deer come out of the woods at dusk. It’s very fairytale-like.”

“I wanted everything to be the way it was. Except, I didn’t want to rebuild in wood.”

Concrete continuance

Walder knew of artists who sculpted works of art from the composite, and she had built countless concrete models in architecture school. While the material wasn’t completely foreign to her, she didn’t know what would happen on site. Casting a concrete shell from the mold of an existing log cabin was an experiment she and, luckily, the builder were curious to dare.

To visualize the construction process for herself and to be able to articulate the steps to her crew, the architect built a model from little sticks and cast it in concrete.

The real hut was set aside by a crane and stripped of anything that wasn’t part of the structure: small laths, twigs, and rocks that inhabitants had stuffed between the logs to chink the walls. The gaps between the logs were then filled with cut-to-fit slats to gain an even leading edge and prevent the concrete mixture from leaking out. Once the foundation was finished, the old-cabin-turned-mold was heaved back in place. The builders constructed the inside of the mold structure with standard form boards. The new cabin was poured in place. After the concrete hardened, the old log cabin was removed and deconstructed.

Poured patina

The original cabin not only lent the new structure its form but also gave it marvelous detailing, most notably a beautiful wood-grain pattern, now preserved in time and stone. The concrete was even the same shade of gray as the old cabin’s weathered wood. The logs left behind a relief ideal for moss to take root and flourish again as it once had.

Walder couldn’t have envisioned all the fascinating effects in advance. “We spent so much time worrying about the construction itself. Will the concrete cling to the cracks in the old logs? Will the corners crumble off?” she remembers wondering. “I was positively surprised and really happy how precise this sculpture turned out.”

Inside, two worlds

Walder decided early on to split the living space into two levels. “Sleeping and living in one room inevitably leads to a camping atmosphere,” she says. The architect aimed instead at designing a much more luxurious retreat with two distinct worlds, upstairs and downstairs.

She wanted guests to feel sheltered in the bedroom below, tucked away in a cave rather than feeling trapped. Thus, she added a large window above the bathtub and a door that leads directly into the forest. “The world of rocks and roots back there reminds me of Alice in Wonderland,” Walder says. “Another door into another kingdom.”

Warm concrete

Concrete may seem to be a debatable material for a cozy cabin in the woods. For Walder, it was the right choice. “The forest in Flims is scattered with the kind of boulders you see from the lower level of the cabin. It’s what makes this area so magical: the caves, the moss-covered rocks. Concrete is not much different. It’s man-made stone. To me, it fits quite well into the setting.”

In fact, some interior features are cast in concrete as well: a pedestal with bathtub and a lavabo on the lower level, and a solid bench along the entire wall beneath the large window on the main floor.

“People are always afraid concrete would be cold,” Walder says. The concrete inside Refugi Lieptgas is actually heated with an under-slab radiant heating system that even loops through the tub and the bench. The concept would not work for a private cabin that’s used only occasionally, because the concrete takes a long time to warm up. With the rental cabin booked solid, however, the stone can continually retain its warmth.

Taking refuge

Literally left without a roof over their heads during the remodel of their own house last fall, Walder and her partner, Georg Nickisch, took refuge at Refugi Lieptgas for a week with their infant daughter and the dog. The architect is pleased with her firsthand experience. “Living there feels very cozy, very protected and private—and at the same time elevated,” she reminisces. “Everything is tiny, but you don’t feel the smallness. You’re in your own small kingdom, separated from the world.” △

"Living there feels very cozy, very protected and private—and at the same time elevated.”

Ice Wide Open

Photographer Chris Burkard finds joy in near-freezing waters just inside the Arctic Circle

When surf photographer Chris Burkard wearied of shooting at tropical beaches and extravagant tourist destinations, he sought out the world’s most remote, stormiest coasts—and found ultimate gratification in Arctic waves. Chris Burkard wouldn’t blame you if you called him crazy for finding absolute joy in surfing just inside the Arctic Circle.

In his talk at TED2015, the renowned photographer shares a story that finds him in the near-freezing waters of Norway’s Lofoten Islands. Chasing perfect waves in the icy ocean with a group of surfers, he could feel the blood leaving his extremities, rushing to protect his organs. “Pain is a kind of shortcut to mindfulness,” he quotes the social psychologist Brock Bastian. The TED session is fittingly titled “Passion and Consequence.”

“Pain is a kind of shortcut to mindfulness.”

His parents didn’t think “surf photographer” was a real job title when Burkard told them at age nineteen that he was going to quit his job to follow his dream of working (and playing) at the world’s most exotic tropical beaches. The self-taught photographer set off in search of excitement but found only routine. A seemingly glamorous career of shooting in dream tourist destinations soon left him ungratified. Constant Internet connection and crowded ocean waves slowly suffocated his spirit for adventure.

Perfect waves in intoxicatingly unforgiving places

“I began craving wild open spaces,” Burkard tells his TED audience. Once he grasped that only about a third of the Earth’s oceans are warm—a thin band around the equator—he began to look for perfect waves in places that are cold, where the seas are notoriously rough. Places others had written off as too cold, too remote, and too dangerous to surf. Places like Iceland.

"I began craving wild open spaces.”

“I was blown away by the natural beauty of the landscape, but most importantly, I couldn’t believe we were finding perfect waves in such a remote and rugged part of the world,” he says. Massive chunks of ice had piled on the shoreline, creating a barrier between the surf and the surfers. “I felt like I stumbled onto one of the last quiet places, somewhere that I found a clarity and a connection with the world I knew I would never nd on a crowded beach.” The icy ocean his new muse, the artist was again intrigued by his subject.

Cold water always on his mind now, Burkard’s newly invigorated career took him to such intoxicatingly unforgiving environments as the frozen wilderness of Russia, Norway, Alaska, Chile, and the Faroe Islands. He spent weeks on Google Earth trying to pinpoint any remote stretch of beach or reef and then figuring out how to actually get to it.

Hypothermic yet happy

In a tiny, remote fjord in Norway, just inside the Arctic Circle, Burkard and his crew encountered a place where some of the largest, most violent storms on Earth send huge waves smashing into the coastline. He was in near-freezing water taking pictures of the surfers (who knows how he managed to push the camera shutter-release button), and it started to snow. He was determined to stay in the water and finish the job, despite the dropping temperature. He had traveled all this way, after all, and found exactly what he’d been waiting for. Wind gushed through the valley. Steady snowfall escalated into a full-on blizzard. Burkard lost perception of where he was. Was he drifting out to sea or toward the shore? Borderline hypothermic, his companions had to pull him out of the water. They told him later he had a smile on his face the entire time.

From that point on, the photographer knew every image was precious, something he says he now was forced to earn. The anguish out there on the icy water had taught him something: “In life, there are no shortcuts to joy.” △

“In life, there are no shortcuts to joy.”

iRetreat

The architects behind Apple stores worldwide design Lake Tahoe weekend homes for Silicon Valley's young tech elite

By creating a community of alpine-modern Lake Tahoe weekend homes, the architecture firm that designs Apple stores worldwide feeds the hunger of Silicon Valley’s young tech elite for authenticity and a real place. Gregory Mottola knows Silicon Valley's young tech elite. The principal leads Bohlin Cywinski Jackson’s San Francisco office, which designs the places where they shop (Apple), work (Square, Pixar), live (modern custom homes in the Bay Area), and play (Newport Beach Civic Center and Park).

The newly rich thirty-somethings working for technology, Internet, and media companies in California’s Bay Area are beginning to seek opportunities to invest their money. And they yearn for authenticity, for a real place, the mountains, the forest. “These folks work in very intense environments, focusing on something that is often very abstract—it’s technology, it’s writing code, it’s engineering things in a virtual space,” Mottola says. “Many of them have a desire to go back and to be connected to real things and to nature.”

Lake Tahoe, California—watersports haven in the summer, snowsports paradise in the winter—is a desirable weekend and holiday destination for the Silicon Valley set. “Some of them are flying their own jets from San Jose to Truckee and are there in a matter of an hour and a half, and the drive isn’t so bad either,” Mottola says. The problem: These urban hipsters appreciate an aesthetic much more modern than the traditional mountain architecture that dominates the Lake Tahoe resorts—Mottola calls that referential chalet and log cabin look “relentless sticks and stones architecture . . . very heavy, overly articulated.”

Weekend-escapists with money

Mountainside Partners, a Tahoe-area developer specializing in resort construction, picked up on the new market need and called Mottola’s team in San Francisco. Why BCJ? That the architecture firm typically doesn’t work with developers didn’t matter. With a design portfolio that boasts Square, Inc. headquarters, Pixar Animation Studios, and Apple retail outlets worldwide, including the (literally) groundbreaking Fifth Avenue store in Manhattan, Mottola and his colleagues understood the target market and the developer's vision for a planned community of progressive luxury ski-in/ski-out residences. BCJ was the ideal partner in rethinking resort living for a new generation of weekend-escapists with money, pouring in from the Bay Area on Fridays after work. And the Stellar Collection at Northstar was born.

Mottola agrees with the developer’s calculation that there is a sizable target audience of young, urban professionals looking for meaningful ways to spend their cash. “With the economy here being so focused on advancing technology, there is the thirty-something crowd, very intelligent and hungry for a connection to a real place, a real landscape, and the recreational opportunities that go along with that,” says the Carnegie Mellon University graduate. The idea of designing not the usual super high-end custom home but a series of spec homes “sounded like fun” to him—“thoughtfully detailed and spatially powerful homes . . . that was a great challenge for us.”

The Mountainside setting

The Northstar resort looks to the north, Lake Tahoe at its back, behind the ski slopes. “It’s a remarkable setting,” says Mottola. “The two ski-in/ski-out sites we are working on flank this ski run, set in such a way that you get these fantastic views of the ski run, the short view of this wooded mountain’s side, and these amazing sunlit views of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Martis Valley as your backdrop.” In siting each home on its parcel, much thought was given to the views and the connection to the landscape. The single-family residences descend down from the driveway—“You enter into this elevated world, you feel like you are perched up in the trees, in your own little world, your own connection to this beautiful Sierra mountainscape,” Mottola says. “Even though the structures are relatively close to each other, you get this little slice of the horizon.” Exit out the lower level, and you are on the ski slope.

“These folks work in very intense environments, focusing on something that is often very abstract... Many of them have a desire to go back and to be connected to real things and to nature.”

Elemental palette of materials

“We are satisfying this appetite for authenticity by using a really elemental palette of natural materials, detailed in a simple way,” Mottola says, describing the “tension” between the natural materials, such as stone floors and wood floors, bringing the outside cedar siding inside—and the contrasting glass and metal. What’s more, Mottola knows energy efficient design appeals to the target demographic. The Stellar Collection is going to be LEED Gold certified; BCJ even hopes for platinum. “Resource efficiency is really important to the folks we design for in the Bay Area.”

Designing spec homes for a developer was a very different process for Mottola's architecture practice, which typically works directly with homeowners. Relying on each others’ respective experience and market studies, BCJ and Mountainside chose the features and amenities they thought would sell. “When we work with a homeowner, it’s a very personal, very tangible connection to them and what’s interesting to them,” says Mottola, adding that yet again some design basics remain constant, such as celebrating the attributes of the landscape by organizing a structure to take advantage of the view and the sun. “All those basic design moves are the same,” the architect notes. “Where this diverges is when you have to assume what will be desirable by buyers whom you don’t know. So we design what we think is really appealing, spatially or architecturally, the detailing in the way the space comes together. The developer has parameters in terms of what they think the market demands, but they are looking to us, our vision for this to be a successful piece of architecture.”

That vision is informed by BCJ’s first-hand experience in working directly with the young tech elite of Silicon Valley. “We do have some insights, because not only are we designing some primary residences for certain individuals in that world, but we are also designing a lot of tech companies’ office spaces,” says Mottola. Seeing what his clients are interested in at work helps him understand what they may want in a primary or secondary home. “For instance, they all crave opportunities to collaborate and share ideas, so you want to design the social aspects of a home in a way that supports that same kind of thinking about how you interact.” A “more prosaic thing” Mottola has learned from creating office spaces for his clientele? “You make a big deal out of really good-quality coffee as the draw for people,” the architect reveals. “Single-source roasted beans, artisanal, handcrafted . . . that attention to detail and interest in the story behind the experience starts to inform the design.” Similarly, his Silicon Valley clients want to know the story behind a building material or interior finish—its source, why the designer chose it, how it relates to the place and makes a homeowner’s experience more authentic. “They care about that detail way more than other demographics seem to, interestingly.”

Designing Apple stores

BCJ has been designing Apple retail stores around the world for more than a dozen years. “The relationship started even before that, when my colleagues here were working with Steve Jobs, doing the Pixar Animation Studios headquarters in Emeryville here, that’s really why we ended up in California,” Mottola says. Steve Jobs purchased Lucasfilm's computer graphics division from George Lucas in 1986 and established an independent company that would later be named Pixar. “At the time, Steve was getting back involved with Apple, and they started this retail program,” Mottola recalls. “At the time, everybody was like, ‘That’s crazy. That’s never going to succeed.’ And you look back now, and you think it’s crazy that that was the prevailing wisdom at the time. But in those intervening years we have been able to collaborate with Apple, doing these remarkable stores in really diverse places, notably the one on Fifth Avenue in New York City, that’s a glass cube.”

According to the architect, who compares experiencing “these really amazing products” in an Apple retail store to “a museum-like setting,” the glass structures many Apple stores feature push the limits of construction through the innovative use of technology. “And then to take those ideas and put them into existing historic buildings all over the world, in places like London and South America and Spain and Italy . . . it’s been a unique experience for our practice, because most often we are hired to do one building for one client. It’s a one-time experience, and you kind of wish you had a chance to go back and do it again. And in the case of the Apple stores, we are constantly refining the design ideas. It’s almost more like product design.”

“In the case of the Apple stores, we are constantly refining the design ideas. It’s almost more like product design.”

Just designers

On the other hand, it seems important to Mottola, who has been with BCJ for almost a quarter of a century, to convey that his firm approaches each design assignment without preconceptions about what the final result should be and instead figures out what it wants to be once his team understands the context, the client, the site. “We want to make sure what we are designing really resonates with that place and with the clients and their dreams and their aspirations,” says Mottola, whose work has won numerous awards from the American Institute of Architects. “We don’t just want to be the Apple store architects or the people who do these great houses or the people who do these university buildings. We want to just be designers. At the end of the day, we are trying to make really compelling, emotionally powerful places for people, whether they are private homes or places where they are doing research or places where they are shopping, we want them to appeal to their hearts more than reason.”

Asked how his experience with designing the Apple stores and workplaces for companies like Square, Inc. has influenced his approach to residential projects, such as the Mountainside Northstar Stellar Collection, Mottola falls contemplative. “It’s hard not to have your experiences influence what you do, absolutely, but the way we think about how a space feels and how you might put fenestration into a building . . . to me it’s just all design.” One thing he is sure his team has learned from designing Apple stores: “Using glass in some homes in remarkable ways we wouldn’t have known how to do without having the experience with Apple. And without a doubt, the research-driven investigation into materials and construction is something we have learned how to do much better, having worked with Apple.”

Designing for the heart

Mottola, who grew up just outside of New York City in Northern New Jersey, knew from a very young age that he wanted to become an architect. “I was fascinated with construction. And once I started to appreciate the way people build things, I began thinking about how do you design and shape space in a way that really resonates with people,” he says. “A lot of people are really good at doing well-considered, responsive buildings, but there is this other layer. Sometimes you walk into a space and you have an emotional reaction to it. You feel something in your heart. Those have always been the buildings I’ve been most drawn to.”

Is designing for the heart taught in design school, though? “You learn a lot in design school about multivariable problem solving, if you really want to get nerdy about it,” Mottola says. “But what I know today about this emotional aspect of design, I actually learned from my mentor here at the firm, Peter Bohlin,” Mottola says, designating the man who puts the “B” in BCJ “a master at creating space that elicits that emotional response.”

“Peter always talks about being inspired by the great Scandinavian modernists, so getting exposed to that work, too, is deeply embedded in the DNA of our practice,” Mottola says. “This idea that you make modern buildings, but you should do it in a way that they are not cold and sterile, but they are evocative and warm and livable and comfortable is something we aspire to do on every project.” △

Stay Different: Whitepod Eco-Luxury Hotel

Go glamping in a geodesic-shaped tent in Switzerland

Les Gaieties / Canton of Valais / Switzerland The 430-square-foot (40-sq-m) pods at the Whitepod Hotel are equally eco-conscious and comfortable. At the foot of the Dents-du-Midi mountain range, a camp of fifteen large geodesic-shaped tents surrounds The Pod-House, which contains the breakfast room, a relaxation area, the bar, and the meeting rooms.

The individual spherical structures are composed of a network of triangles that create a self-bracing framework (you can figure out the architecture in detail as you lay in bed). Each cozy pod is uniquely decorated with local antiques and artifacts. The light-filled pods of various configurations each include a king-size bed, full bathroom, wood-burning stove, and even a terrace to sit outside and take in the breathtaking alpine views.

Sleep Elevated

7 alpine-modern places to stay in the Alps

From a remote minimalist hut to a decadent chalet fit for the royals, modern design lovers stay happy in these hotels and vacation rentals at — and high above — stunning mountain resorts in Switzerland, Austria, Italy and France.

Monte Rosa Hut / Switzerland

Modern mountaineers bunk at the 120-bed Monte Rosa Hut with grand views of the Matterhorn. More »

Wiesergut Design Hotel / Austria

Set against a bucolic backdrop of ski slopes and hiking trails, luxurious suites, a splendid spa and exquisite cuisine make Wiesergut a rare alpine retreat. More »

Whitepod Eco-Luxury Hotel / Switzerland

Sleep in a geodesic-shaped tent at the Whitepod Hotel for an entirely different vacation experience without sparing the comfort of a king-size bed and a full bathroom. More »

-

Feldmilla Design Hotel / Italy

The Feldmilla Design Hotel in South Tyrol offers panoramic views of the Dolomite mountains and uses clean energy from its own hydro-power plant. More »

Chalet Les Gentianes / France

Part of a quiet residence in the world's largest linked ski area of Les Trois Vallées, chalet Les Gentians has a swimming pool, Jacuzzi, massage room, and gym. More »

Kristallhütte / Austria

Hotel and hipster après-ski hangout of the moment, the Kristallhütte sits slope-side in the ski area of Hochzillertal Kaltenbach. More »

Chalet Zermatt Peak / Switzerland

Indulging in little extras, such as a personal chef and serving staff, the rich and the royals have stayed at Chalet Zermatt Peak in pure luxury, with grandiose views of the Matterhorn. More »

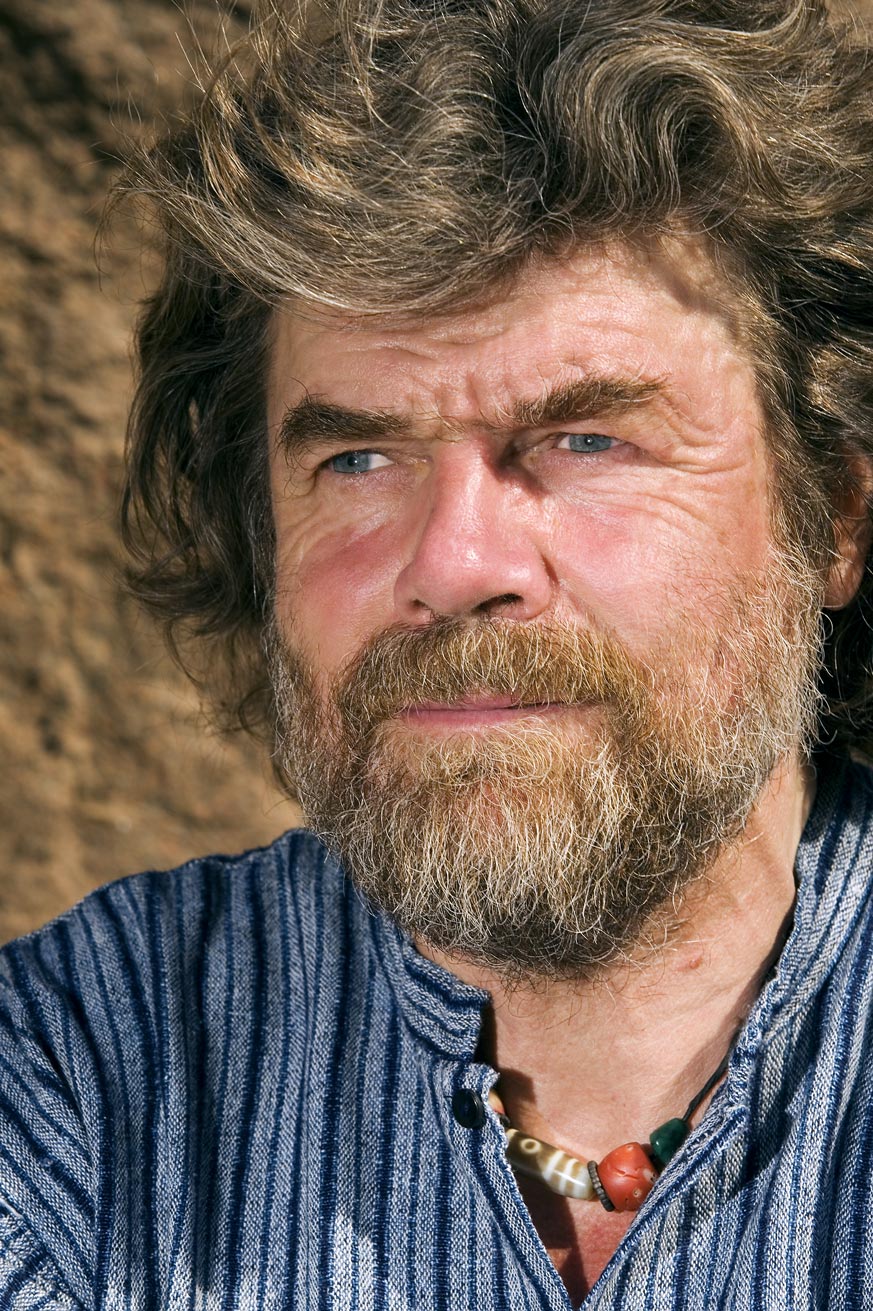

Reinhold Messner: A Man and His Museums

A conversation with the greatest mountaineer of all time

We met with the mountaineering legend in the Dolomites, where the late architecture icon Dame Zaha Hadid designed the last of Messner’s six mountain museums: MMM Corones. Emerging surrealistically from the earth at the top of a mountain called Corones in northern Italy are huge concrete tubes. One writer described them as resembling “a spaceship that has crashed into the peak and fused with the rock.” They are, in fact, apertures from a literally and curatively groundbreaking subterranean structure. They are the most unique features of MMM Corones, the last of six Messner Mountain Museums and the latest chapter in the extraordinary life of seventy-two-year-old Reinhold Messner, widely acknowledged as the greatest mountaineer ever.

The Italian mountaineer with the German name continues, in today’s parlance, “to give back.” His sixty or so books, films, lectures, and five-year tenure as a Green Party member of the European Parliament assure his legacy. And then, there are his museums—six of them, each with a different theme—located in northeastern Italy. Collectively known as the Messner Mountain Museums, they acknowledge and celebrate the world’s mountains and honor human relationships with them. Some have been built within the walls of ancient buildings, while others are brand new and no less than revolutionary.

The newest sits atop Corones (Kronplatz in German), which ranks as one of the Dolomites’ largest year-round recreational playgrounds. Skiers throng to it in winter, and hikers, mountain bikers, and parasailers have been dis- covering it in summer. Now MMM Corones also makes it a secular pilgrimage place for those who also revere mountains and the humans who live among them—and for the legions who worship Reinhold Messner.

Perhaps Messner became aware of Hadid’s talents from the large ski jump up the road in Innsbruck, which she designed in 1999 and which is used for the FIS Ski Jumping World Cup. Hadid later received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004. For Messner, she designed MMM Corones, which opened in July 2015. Just two months later, the Royal Institute of British Architects announced her as the first female recipient of the Royal Gold Medal—instituted in 1848—for lifetime achievement. Sadly, only eight months after MMM Corones opened its doors, the museum's esteemed architect died suddenly. Hadid had contracted bronchitis in March of 2016 and suffered a heart attack while being treated in the hospital.

"The theme is rock—original, traditional mountain climbing is to rise again."

His concept was very specific: “In the first tunnel, a window looking out southwest to the peak of the Peitlerkofel mountain, in the second, another window should look south toward the Heiligkreuzkofel peak, and in the third, a balcony should face west to the Ortler and South Tyrol.”

Hadid took those concepts and ran with them. Above the entrance to the three-level museum is a sharp glass canopy that evokes a fragment of glacial ice. Inside, ramps and staircases recalling mountain streams and waterfalls link concrete galleries in a flowing, organic fashion that feels like a smooth cave. The windows frame the mountains, providing constrained, controlled views. The best one opens exuberantly to a terrace cantilevered over the valley far below; the view is panoramic, simply stunning.

Hadid said of the structure, “The idea is that visitors can descend within the mountain to explore its caverns and grottos before emerging through the mountain wall on the other side, out onto the terrace overhanging the valley far below with spectacular, panoramic views.”

The museum is also environmentally correct. Being mostly underground, it maintains a consistent year- round temperature. An impressive 140,000 cubic feet (3,964 cubic meters) of earth was excavated and moved during the construction process, but once the building was nished, covered, and revegetated, its footprint became modest. Its design emotionally and visually links the mountains outside and the exhibits inside, which honor the tools and techniques of traditional mountaineering that are Reinhold Messner’s roots.

Messner’s Extraordinary Mountaineering Feats

None of this modern repository to the mountain heritage would exist without Messner’s unmatched feats in the high, wild, and remote parts of the world. He was the first to climb all fourteen of the world’s 8,000- meter (26,247-feet) peaks, which are known as “eight-thousanders.” He was determined to complete all of these mountains, and achieved some only on the third or fourth attempt. He also was the second to climb the legendary “seven summits” (the highest peaks on all seven continents) and the first to do so without supplemental oxygen, including Mount Everest. In fact, he stood on the top of the world’s highest mountain twice, first with his Austrian climbing partner, Peter Habeler, from the Nepalese side, and once soloing from the Tibetan side—during the monsoon season.

Messner’s first major Himalayan climb was back in 1970. He and Günther were part of an expedition to the previously unclimbed Rupal Face of Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat. Terrible weather forced them to make an emergency bivouac at the summit—no tent, no sleeping bags, no stove. In the morning, they started down in a storm via the Diamir Face, a different route. It was to be a tragic day. Reinhold lost six toes to frostbite. He also lost his brother to an avalanche. He returned to the mountain to search, unsuccessfully, for Günther’s body, which did not emerge from its icy tomb until a heat wave in 2005. That awful experience thirty-five years earlier and the harsh judgments of the mountaineering community would have been more than enough to deter a less intense man from other expeditions. But he continued exploring, achieving, and learning.

In Messner’s youth, expedition climbing pioneered by the British was the norm. He soon became convinced that such massive expeditions were not only counterproductive to the chance of success in conquering high peaks but were in his view, cheating, because guides and porters did all the hard work. He was a pioneer in what has come to be called “alpine-style climbing,” carrying everything he needed on his back and moving as quickly as possible. These climbs, either solo or done with just one or two partners, not only led to success but were less impactful on the mountains.

Over the years, Messner became increasingly captivated by mountain cultures with people’s beliefs expressed in art, spirituality, and convictions. He brought back artifacts and photographs from his expeditions to distant mountain ranges in exotic places. After a time, he turned his attention from the vertical world of mountains to the more horizontal realm of epic treks across wild, largely empty land. Long overland slogs—across the Greenland ice sheet, across Antarctica via the South Pole, and across Tibet—without snowmobiles or other machines and only the most minimal communications equipment. The miles and the vastness left time for contemplation and sometimes hallucinatory visions of what was, what might be, and what could be when he returned home.

The Tale of the Hammer

One memory that remained etched in Messner’s mind for decades involved a single climbing implement, a hammer. While still in his twenties, he wrote an essay about rock climbing whose title translates to “Murder of the Impossible,” in which he lambasted the increasing use of bolts and assorted gadgets to meet and overcome climbers’ greatest challenges. “Faith in equipment has replaced faith in oneself,” he wrote at the time.

After it was published, Messner received a letter written in a spidery hand from a then ninety-six-year-old Austrian lady. Messner recalls, “She said, ‘Reading your article, I was reminded of my boyfriend, my big love, Pauli.’ ” Pauli was Paul Preuss, an early advocate of reliance on skills and courage and not a lot of gear, as Messner would proclaim decades later. Preuss did have a hammer but, as the story goes, was opposed to pounding pitons into rock if it could be avoided. “He had two pitons in his life,” Messner told a reporter years later. “One I have, and the other is in a rock wall that I know.” Preuss was committed to such a purist approach despite its greater risks. In 1913, when he was twenty-seven, Preuss fell to his death while free-soloing the North Ridge of the Mandlkogel, a peak in Upper Austria.

He was one of Reinhold Messner’s climbing heroes. Messner was honored when the lady sent Preuss’s hammer to him because his philosophy and climbing style echoed her beloved’s. She stipulated that after Messner’s death, the precious object had to either be passed on to another like-minded climber or be put on display. Messner recalled, “I had that hammer in my cellar, and always when I saw it, I was thinking, ‘Oh, I have to begin a museum.’ Around this hammer the whole museum idea began to grow.” And that is how the Messner Mountain Museums came to be. The hammer that started it all is appropriately on display at MMM Corones.

"I had that hammer in my cellar, and always when I saw it, I was thinking, ‘Oh, I have to begin a museum.’ Around this hammer the whole museum idea began to grow."

But before Corones came five other museums. MMM Juval was the first, opening in 1995 in Juval Castle near the town of Vinschgau. Its theme is mountain myths, and in addition to proving that a mountaineer could conceive, open, and curate a museum, it serves as the Messner family’s summer residence.

MMM Dolomites, housed in a World War I fort on Monte Rite near the town of Cortina d’Ampezzo, opened in 2002. Its theme is the “vertical world” of the Dolomites, covering the opening up of this once-remote range and its history in peacetime and in war. During World War I, this was the region where mountain warfare was first conducted. Both sides’ dreadful losses came more from severe cold, rockfalls, and avalanches than combat.

MMM Ortles’s theme is the realm of snow, glaciers, and the world of ice in general, and expeditions to the poles in particular, environments that Messner has experienced intimately. Built into the mountain on a hillside near Sulden, it opened in 2004 and features art and artifacts to depict the power of avalanches and other forces of nature. When asked about global warming and climate change, Messner’s Green Party side rues what is happening to the planet these days, but his alpinist side comes out when he says, “We feel global warming in the mountains, but heat is not a problem for climbers. Cold is more of a problem.”

MMM Firmian in Sigmundskron Castle near Bolzano houses the museum’s headquarters, event space, rotating exhibitions, and a 200-seat theater. Devoted to the history and art of mountaineering, it is a modern museum built within the ruins of a fifteenth-century castle. Messner spent five years negotiating and planning Firmian, which opened in 2006. Architect Werner Tscholl, a specialist in castle conservation, created exhibition space without destroying the original. The challenge was to preserve the historical walls of the castle in such a way that the new construction can be reversed if ever required or desired. The new parts are a background for sculptures, photos, symbolic objects, and mementos that Messner collected on numerous expeditions, as well as an annual special exhibition.

MMM Ripa at Bruneck Castle, which dates from 1250, is the most intense cultural expression of Messner’s experiences. It opened in 2011 as the fifth Messner Mountain Museum. Dedicated to the mountain peoples from Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe, it focuses on cultures, religions, and even tourism. This interactive museum provides a forum for various mountain peoples to exchange experiences with the vibrant local farming community.

Reinhold Messner has spent his life seeking what he admits have been “the most difficult challenges,” not the least of them being the creation of the Messner Mountain Museums. He calls them “my fifteenth eight-thousander,” with MMM Corones the crowning achievement. His daughter Magdalena is now running the museums. But he is far from finished creating, exploring, and honoring.

In September, he set off for Africa to produce a film about a harrowing 1970 expedition to Mount Kenya. Drs. Oswald Oelz and Gert Judmaier from Innsbruck attempted to climb Africa’s second-highest mountain when disaster struck. A sudden rockfall swept Judmaier and a huge boulder down the mountain. It was a miracle that he survived at all. Grievously injured, he clung to life for nine excruciatingly painful days. Oelz ministered to him as best he could under dire conditions and with few supplies. Finally, an elite mountain rescue team flew to Nairobi, rushed to Mount Kenya, and managed to get the party off the mountain while Judmaier was still alive. It is a story that only Reinhold Messner could understand and film. He might consider its completion to be his sixteenth eight-thousander.

Photo Gallery

Quietly Swiss

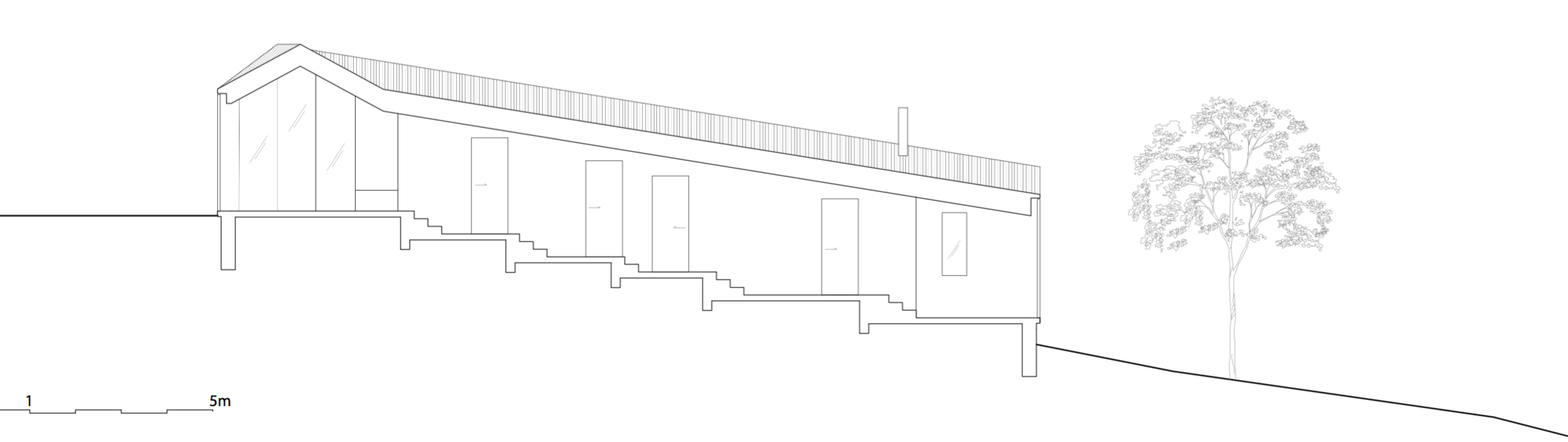

A chalet shaped after the surrounding mountains of Les Jeurs

Local building nostalgia and the majestic surrounding mountains guide Geneva architect Simon Chessex in designing a young couple’s modern dream house, built on family land. Olivier Unternaehrer, a Geneva-based attorney, and Céline Gay des Combes Unternaehrer, a professional harpist, had long dreamed of a mountain retreat where they could spend weekends and holidays, someday raise a family, and eventually retire. So when the young couple had the opportunity to own a plot in the mountains of Les Jeurs—land that had been in Céline’s family since the 1800s—the decision to build there was obvious. A hamlet above the road to the Col de la Forclaz mountain pass in the Swiss Alps, Les Jeurs was the perfect place.

Adventures in architecture with Lacroix Chessex

Longtime friend Simon Chessex, a founding partner of the Geneva architecture firm Lacroix Chessex, was the natural choice as Olivier and Céline’s architect. The couple shared their requirements, nice-to-haves, and wildest dreams with Chessex and his team, and the collaborative design process was “a beautiful adventure,” Olivier says. “We believe—and we think they do, too—that we brought the best out of each other throughout.”

Simon Chessex founded Lacroix Chessex with fellow Swiss architect Hiéronyme Lacroix in 2005, based on their shared belief that good architecture is inspired by two factors: “a thorough analysis of the site, in which micro and macro scales are directly related, and a careful and critical reading of the brief that is given to us,” Chessex says. Both partners strive to approach design and construction without preconceived ideas of what a project should become. The role of the architect, says Chessex, “is that of a tailor who designs and realizes a client’s vision with care, passion, and accuracy.”

Roots on family land

The home’s spectacular location near Trient was destined. Céline’s ancestors were native to the region. As a child, her own father spent many holidays camping on the very land where Céline and Olivier would later build their chalet. Sharing the same dream of raising a family in these majestic mountains a generation earlier, Céline’s parents relocated from Geneva to Les Jeurs in the 1970s. And decades later, as a couple, Oliver and Céline spent weeks at a time, even one entire summer, vacationing in the mountains. When Céline’s father offered them a plot of the family land, their decision to build there was a simple one.

Like generations before them, committing to the family land for a lifetime felt timely. They pictured a mountain retreat where Céline could play the harp, where they could soon raise a family, and where they would eventually retire. “Our vision was to build a house that would be a place to welcome friends and family, that would fit well in the local and mountain landscape, yet that would be modern,” Olivier says. Chessex absorbed their hopes and dreams and presented plans for his reinterpretation of a traditional Swiss chalet.

The architect drew upon the region’s historical stone and wooden mountain homes for inspiration and let the alpine landscape guide his design. “It’s clearly a site-specific project,” Chessex notes. “The shape of the building comes from the profile of the surrounding mountains.” It was important to Olivier and Céline that the house was modern yet also fit into its “quite wild” setting. And Chessex’ design beautifully harmonized with the local village homes and the spectacular scenery. Aware that a closed, large volume would disturb the harmony of scale, the architect designed the structure as two parts forming a “V.” They are connected by the entrance on the mountainside and are separated by a forty-five-degree angle that opens toward the valley. “The numerous windows give many opportunities to just look outside and bring the outside to you, just as if you were looking at a painting,” says Olivier.

"The numerous windows give many opportunities to just look outside and bring the outside to you, just as if you were looking at a painting."

The landscape and the design are in “smooth and direct relationship,” he continues—inside the “cozy chalet atmosphere” and outside views of the “playground.” Reinterpreting the functional design of historical Swiss barns that were elevated from the ground to preclude mice from entering, Chessex situated the home on a cantilevered concrete plinth. He chose grey fir wood for the home’s exterior and natural fir for the inside because the material is both naturally weather-resistant and economical.

Bridging cultural integrity and modernity with stone and wood

Chessex used the same wood for the walls, ceilings, and floors so that the interior uniformly appears as a single unit of space. This element of the composition is unsurprisingly one of Olivier and Céline’s favorites. Olivier believes the house bridges cultural integrity and modernity by keeping things as simple as possible. The natural quality of the wood reminds him of older mountain dwellings marked by the years, wind, and snow.

At the same time, Chessex took the liberty to put an updated twist on traditional Swiss mountain architecture by designing the home as two connected wings: The main entryway is “folded where the two buildings unite,” creating a V-shaped front door and window. Olivier shares that abandoning tradition to incorporate modern eaves “clearly surprised some people at first,” but was ultimately very well received. The owners particularly enjoy the the roof’s geometry and the living room window that reaches down to the floor.

The rugged mountain location complicated the construction process. Inaccessible by truck, the site required helicopters to fly in prefabricated wooden pieces. Additionally, Chessex initially worried that the authorities and local population might find the house too radical for the village and feared he may be denied a building permit.

Despite the challenges, Olivier and Céline were able to move in exactly two years after hiring Chessex to design and build their home. Olivier describes the experience: “Quite simply, one day we could walk in, and the house was no longer the worksite it had been for the last year, but a complete house in which we could stay. It was quite an intense and beautiful moment.”

"Quite simply, one day we could walk in, and the house was no longer the worksite it had been for the last year, but a complete house in which we could stay. It was quite an intense and beautiful moment."

Olivier and Céline quickly fell in love with the mountain house and now spend their weekends there after a week’s work in Geneva, where they have been renting the same apartment for more than ten years. Olivier contemplates how the modern chalet is “majestic, like a quiet force, as the mountains can be.” From the exterior, “The house appears to be changing shape depending on the viewing angle,” he remarks. Inside, the home feels “peaceful, relaxing, and quiet” with direct views of nature and mountain wildlife.

Visiting friends often refer to the couple’s hideaway as their “nest,” given it’s high mountain perch—a dual meaning, since the couple hopes to raise a family in their “lifetime house,” as Olivier calls it. “We intend for our house to become a family home and at all times to remain a place where friends and guests can come and share good times with us.” What started as their self-admittedly “crazy” dream materialized into a beautiful sanctuary on the mountainside, a home daringly designed to mirror the innate artistry of the surrounding landscape and to nourish creativity and community.

"We intend for our house to become a family home and at all times to remain a place where friends and guests can come and share good times with us."

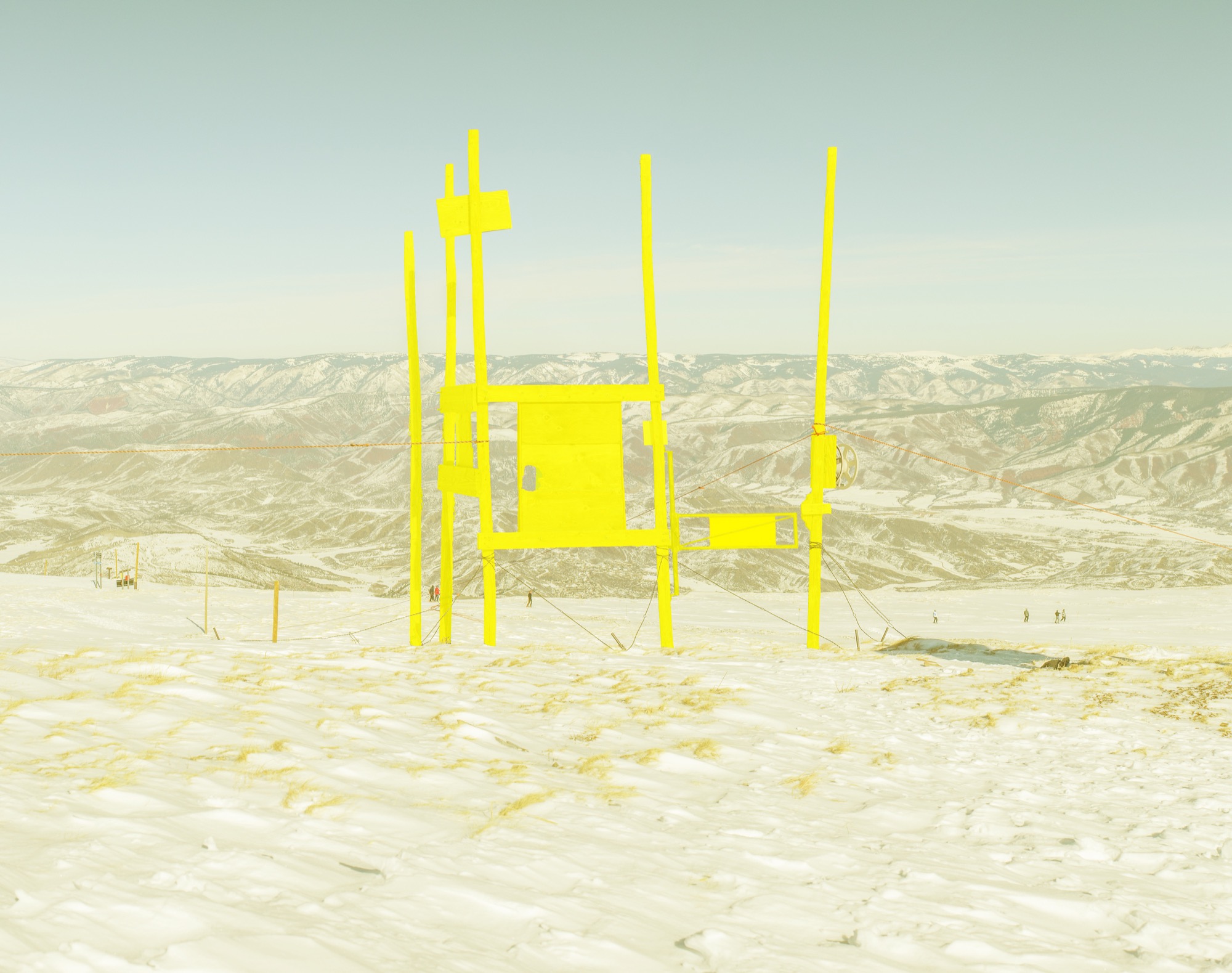

Becoming JK

Meet the immensely talented photographer and artist behind our JK Editions

A studio visit with Colorado photographer and artist Jamie Kripke, who experiments with layers of images and color to create JK Editions.

Growing up in northwest Ohio, Jamie Kripke received mixed messages about making a career out of his love for photography. His mother, herself an artist, passed down her old Minolta camera to her son when he was fifteen. His father’s decision to buy a condo in Snowmass, Colorado, when Kripke was three jump-started a lifelong love affair with the mountains at a young age.

Kripke started snapping photos for the school newspaper at his Toledo high school. At the time, his mother’s 1973 Minolta XG-M with the macramé strap was “a gnarly camera to have for a kid,” he tells me. While his peers were playing with point-and-shoots with flashcubes or Kodak Instamatics, Kripke was teaching himself how to vary aperture and shutter speed for the perfect shot. He developed his own film and made prints in the school’s darkroom. His first published photo is a slim black-and-white of the high school football coach jogging toward the lens. And yet, Kripke put thoughts of pursuing a photography career out of his mind because “when you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

“When you grow up in the Midwest, being an artist isn’t really on the list of things your parents want you to do.”

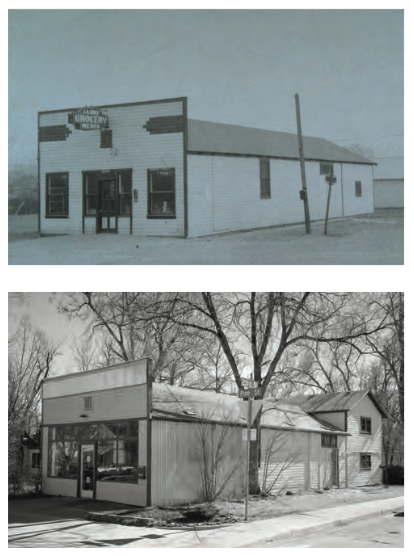

Today, Kripke is a professional photographer whose clients include Hewlett-Packard, Sony, Mini Cooper, and Visa. His editorial work has appeared in Dwell, Esquire, Outside, The New Yorker, Wired, and other publications. I join him at his Boulder, Colorado, studio on an unseasonably warm January day to learn more about his journey from high school newspaper photographer to successful independent artist. His corner studio has a deep history in the community, formerly operating as the local grocery, and before that, a horse stable. He’s been told that ghosts linger in the space. The white-walled studio is open and bright. We sit across from each other on facing vintage couches: mine a stormy gray with a mustard-yellow throw pillow, his a popping pink with a jade accent.

A simple white coffee table sits between us on a colorful striped rug. My eyes are drawn to a round clock hanging on the wall to my left; in place of numerals are songbirds—curiously, my own grandmother, mother, and aunts in Ohio all own one of these very clocks (my interviewee and I share the same home state). When I ask Kripke about the peculiar timepiece, he tells me that his father’s company in Toledo developed the original bird clock. “It has always been on the wall wherever I work as a reminder of my dad, his work ethic, and his business savvy,” he shares. Four mismatched desks of varying heights line the wall under the clock; there are no typical office chairs, but one desk has a short neon-orange children’s stool pulled up to it. The opposite wall is covered in framed black-and-white landscapes.

Kripke is a calm man; he sits cross-legged in jeans and a plaid shirt, answering my questions in a slow and intentional cadence. He explains that adventuring in the mountains of Colorado from a young age led him to the natural choice of moving to Boulder for college, where he dabbled in majors including pre-med and business before settling on philosophy. All those years, he was shooting photos with his old Minolta. In his bedroom back in Ohio, he had a poster of Bill Johnson, the downhill skier. He describes the image as a razor-sharp shot of the skier, airborne in a tuck and looking right into your eyes. As a kid, he’d often stare at the poster, wondering how on earth someone got that shot. On weekend ski trips to the mountains during college, he’d play around with photographing his friends:

“I was burning tons and tons of film to get one picture that didn’t suck.”

Kripke’s first breakthrough came a year or two after graduation, when Powder Magazine offered him seventy-five dollars for one of his images. This was a landmark moment in his photography journey; he recalls thinking, “Whoa, you can shoot pictures and get paid? That’s awesome.” The check and the letter from the magazine editor confirmed his deep longing to capture the world around him with his lens. He followed his curiosity to San Francisco, where he began assisting established studio photographers, a learning experience he likens to his graduate school. Spending much of his free time at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he began diving into the world of fine art.

Observing other photographers and artists led to a natural curiosity about their techniques and guided him in finding his own approach. “[Photographer William] Eggleston was one of the first guys to pay attention to everyday stuff and to the ugly stuff. All of a sudden, I fully grasped this idea that photos are everywhere around us all the time, and it’s a little overwhelming.” Kripke’s interest in composition was sparked by Stephen Shore, who had a “gift for finding these compositions where your eye follows the path through the image. For me it’s like a seven-course meal.” And Jeff Wall, a Vancouver-based photographer who spent an entire year constructing one photograph, inspired Kripke to make the move from “something you find that already exists to something that you create from scratch yourself—taking versus making.” If he wanted to get serious about photography, he knew he needed to be able to make.

One day, while living in California, Kripke saw an old car with a mattress tied onto the hood driving on the highway. He laughed out loud at the curious sight and instantly knew he wanted to re-create that scene in a photograph. He left a note on his neighbor’s station wagon, got an old mattress from a homeless shelter, and researched how to light a moving vehicle. “It was the first picture I really feel like I made, that I fully put all the pieces together.” He still keeps that photo in his portfolio, even though it is ten years old. He reflects on the elements he pulled together from his role models: Gregory Crewdson’s moody lighting, Robert Bechtle’s nostalgic subject matter, Stephen Shore’s composition. “In some ways this picture encapsulated all this stuff that I had been paying attention to up until that moment, and I was lucky to be able to turn it into a single image.”

The plunge

All the while, Kripke still had one foot in and one foot out of photography as a profession. “There are different stages of commitment. There’s the first stage where you think, ‘Hey, maybe I should try this.’ But there’s another stage, much farther down the road, when you have to be really serious and make a real commitment to not turn back.” While working as an assistant to other photographers in his twenties, Kripke had a paycheck to count on. But could he build a viable career on his own? Unsure, he met with a career counselor when he was around the age of thirty. “I was at a point where it was time to decide,” he remembers. That’s when he got the push he needed: “The career counselor asked me what’s been the longest relationship I’ve ever been in, and I said, ‘About a year.’ Then she asked me how long I had been taking pictures, and I said, ‘Since I was fifteen, so fifteen years.’ And she looked at me and said, ‘It’s time to get married, Jamie—to photography.’ That was the moment I knew it was time to go all in—not look back.”

Kripke decided to make the leap and commit to supporting himself with his craft, so he continued to self-educate by following his curiosity and seeking out teachers. He took photography trips. He drove a VW Bus around Europe in 2004, chasing inspiration until the van broke down, stranding him in the “Des Moines of Spain,” which provided new photography challenges for a long three weeks. Back in the States, he traveled to Santa Fe to study with Dan Winters, a portrait photographer whose work Kripke first saw in The New York Times Magazine. Finding an agent in San Francisco allowed him the flexibility to move back to Boulder. He now lives a block away from his studio with his wife, Kate, a psychotherapist, and his two daughters: nine-year-old Kinley (nicknamed “Nugget”) and six-year-old Bridger (aka “Hot Sauce”).

When I ask Kripke about his favorite creative project, he laughs: “Am I allowed to say Alpine Modern?” In addition to cover art and a black-and-white photo essay—“Alps // 40”— Kripke’s fine art photography series “JK Editions” has been featured in our printed magazine, issues 03 through 06. “I’ve really loved creating these landscapes for Alpine Modern because it brings together so many things that I enjoy—skiing, photography, art, being outside, exploring, creativity.” Kripke has come to the Rocky Mountains since he was three, and now as a Colorado resident, the alpine landscape continues to inspire his art: “The mountains are like my sanctuary. The mountains are where I go to recharge and be inspired and to exercise and to push myself and to build friendships and to scare myself. They offer so many ways to make us better people—or make me a better person.”

Color connections

The JK Editions use layers of photography, art-driven references, and color. Kripke begins each project by photographing architecture or landscapes. Back at the studio, he zeros in on what captured his attention in the first place and layers these elements with color: “We have emotional connections to certain colors, so the color is about trying to create that connection.” We walk over to the desk, where Kripke shows me his recent work for Alpine Modern: He layered six or seven photos of the same landscape in different seasons one on top of the other to create one complex image. The winter and summer scenes are stitched together, artistically suggesting spring.

He describes the experience of displaying his work: “When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Some of the best advice Kripke has received as an artist is to “change up your inputs.” He continues to look beyond photography for inspiration, seeking out painting, sculpture, music, books, and podcasts to avoid stagnating in one medium. His work is a reflection of this: “I think inspiration comes from unlikely places or maybe the combination of two things that you didn’t expect to see together.” He seeks to make something new by combining photos and mediums to progress a project “somewhere it hadn’t been before.”

“When I put images up, I like to think of them as windows. If you treat it like a window instead of a print hanging on the wall, it behaves differently, and it offers you a way to transport yourself somewhere for a moment.”

Kripke’s philosophy on life? “Just be honest with yourself, and be honest about what makes you happy.” When I ask him if there is anything else he would like to share, he laughs: “Everything’s for sale.” △

In Praise of Walks and Wilderness

To be human in the mountains is to be fragile

Writer and poet Haley Littleton seeks out fragile moments of being that exist in nature—on trails, summits, and cliffs. Climbing mountains and wandering forests, we feel intoxicatingly happy and at once meek in our undefended bodies provoked toward the verge of physical capacity. The alpenglow illuminates the tips of the adjacent ridge as we crest the saddle of the trail. We have settled into our gait and into silence, elongating our steps to reach a lookout point from the gray, shifting scree field. A moun- tain goat follows our path up the rocky steps, and we pause at the top for a breath, a view, and water. This is a moment when I feel extraordinary happiness. It doesn't matter that in our ascent of Mount Sherman, we missed the peak three times, ascending three different 13,000-foot (ca. 3962-meter) peaks instead, or that our planned three-hour hike turned into six hours. I was content to crouch down and stare at the mauve and olive-colored succulent plants that lined the ascent to the peak and wonder what species they were. I was not concerned when or how we would reach the eventual summit.

When critic and poet Charles Olson spoke of poetry, he spoke of walking and of breathing. He spoke of measuring the line of the poem to the rhythm of breath. This “projective verse” called the whole body of the poet into measure. This is a form of “frolic architecture,” as Olson calls it, which one might consider artful kinesiology: to trace out lyric and language with body and space and mountain. By being a participant in nature, one is able to listen and then create from this space. We’ve all had those moments when we step out into the fresh mountain air: breathe in, breathe out, recenter.

It’s like Moab this past March: While back home was filled with uncertainties, rifts, and unpleasant memories, to stand upon the plateau and look across at the deep tannish reds, browns, and yellowish greens of Upheaval Dome—cuts made thousands of years ago—even in the sweltering heat and the sweat of the hike, I felt a peace I have not found elsewhere. I stood and thought of Edward Abbey’s words in the preface of his book Desert Solitaire:

Benedicto: May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end, meandering through pastoral valleys tinkling with bells, past temples and castles and poets’ towers into a dark primeval forest where tigers belch and monkeys howl, through miasmal and mysterious swamps and down into a desert of red rock, blue mesas, domes and pinnacles and grottos of endless stone, and down again into a deep vast ancient unknown chasm where bars of sunlight blaze on profiled cliffs, where deer walk across the white sand beaches, where storms come and go as lightning clangs upon the high crags, where something strange and more beautiful and more full of wonder than your deepest dreams waits for you beyond that next turning of the canyon walls.

More full of wonder than your deepest dreams, indeed. I kept looking over to my friend, continually proclaiming: “I can’t believe how happy I am here.” I understood Abbey’s fierce ecological devotion to the place. Preservation begins with appreciation; it begins with experiential love. “Earn your turns,” a friend always calls out, strapping his skins to his skis and hoisting his body up the incline. Another pal takes off to the mountains when big life decisions loom in front of him: “It’s the only place quiet and still enough to think.” One hikes fourteeners to prove to himself that his body is capable of more than he believes and that what others say about him is not the whole story. One of my best friends may have hated the peak I dragged her up during our climb, but afterward she turned to me and sighed, “I’ve never felt more alive or more in love with my body.” Once, on a backpacking trip with high school senior girls, one turned excitedly to me and said, “I haven’t thought badly about my body this whole trip!” I think of my skis hanging over the ledge of Blue Sky Basin, my toes hurting like hell, my legs are tingling and frozen, and my flight-or-fight mode tells me that the drop in isn’t worth the potential outcome of pain. But when I look up at the snow-crested ridges against the deepest blue backdrop I’ve ever seen, I push on and fire up my legs, reminding myself that this view is worth the discomfort it takes to reach it.

In an age that saw the rise of print reproduction, philosopher Walter Benjamin spoke of original art as containing an “aura” that reflects its presence in time and space: the sentiment contained within and the value connected to an experience with art. It's a sense that mirrors the way we sometimes want to touch a piece of artwork on the walls to simply feel it, as if to be a part of it. This same aura exists in nature: “If, while resting on a summer afternoon, you follow with your eyes a mountain range on the horizon or a branch which casts its shadow over you, you experience the aura of those mountains, of that branch,” says Benjamin. Sculptor Andrew Goldsworthy embodies this idea of “nature aura” in his entirely nature-derived pieces made from branches carefully arranged, leaves woven together, stacks of rocks or ice melted and refashioned, all of which rest entirely upon impermanence. Happen upon his works before they are gone.

If human sense perception changes with historical circumstance, what does the recent technological boom and rise of virtual realities do to our perception of nature? Why does climbing a mountain matter if we can see the same view on Instagram? Why does visiting a location matter if Google Earth offers us the same view from the sofa? It seems this sense of feeling is disappearing as the search for experience is constantly digitized and commercialized. We pry a thing from its shell and market the hell out of it. We want things to be more accessible, to be easy to get to, so we pave roads on the tops of fourteeners and take all risk out of our outdoor adventures. Or, we consistently see pictures on social media of beautiful scenes and stay content to remain inside. But there’s something about the body that matters. There’s something about being there that we miss.

Ecologists speak now of a need for “deep ecology,” not just an understanding of ecological issues and piecemeal scientific responses, but an overhaul of our philosophical understanding of nature. Instead of viewing mankind as the overlord of nature, it’s about revisiting the idea that a give-and-take relationship exists between the human and the nonhuman, a relationship that thrives on mutual respect and appreciation. To develop this sort of appreciation for nature and the nonhuman, it matters that we actually experience it. For many ecological thinkers, walking among mountains can be the first step in healing a false split between body and mind. The grief at the destruction of a beautiful building, the ecstatic joy of a sunrise in the mountains—these moments stem from this unification of the two.

“For many ecological thinkers, walking among mountains can be the first step in healing a false split between body and mind.”

Fragile moments of being that exist in nature

It’s a question of place versus nonplace. In The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities, Richard Sennett points to the peculiarity of the American sense of place: “that you are nowhere when you are alone with yourself.” Sennett speaks of cities as nonplaces, in which the person among the crowd slips into oblivion, only existing inside him- or herself. Other nonplaces look like the drudgery of terminals or waiting lines or places where all eyes are glued to phones. The buildings are uniform, and the faces blur together to create a boring conglomerate of civilization. If to be alone in a city is to be nowhere, the antithesis must be that to be alone in nature is to be everywhere. Nature is a place characterized by its “thisness,” as Gerard Manley Hopkins describes it—a place to enter into that is palpable with its own essence and feeling.

But as we lose our connection to place, as virtual reality turns here into nowhere, we lose our ability to narrate our experiences of nature. Recently, nature writer Robert Macfarlane pointed out that in the Oxford Junior Dictionary, the virtual and indoor are replacing the outdoor and natural, making them blasé. When we lose the language to describe our connection to landscape and place, we lose the actual connection to these things and the value decreases, separating us from the natural. According to Macfarlane, we have always been “name-callers, christeners,” always seeking language that registers the dramas of landscape, and the environmental movement must begin with a reawakening of natural wonder–inspired language.

Perhaps the point of all of this is to work to develop more refined attention, an ability to seek out and perceive fragile moments of being that exist in nature. We must pay attention to our breath and our bodies. Wendell Berry, a prophet of the natural, writes that to pay attention is to “stretch toward” a subject in aspiration, to come into its presence. To pay attention to mountains, we must come beneath them and reach out toward them.

To walk is to perceive

How do we begin? By wandering within the wilderness. Rebecca Solnit’s book on walking comes to mind: “Walking is one way of maintaining a bulwark against this erosion of the mind, the body, the landscape, and the city, and every walker is a guard on patrol to protect the ineffable.” While people today live in disconnected interiors, on foot in wilderness the whole world is connected to the individual. This form of investing in a place gives back; memories become seeded into places, giving them meaning and associations both in the body and the mind. Walking may take much longer, but this slowing down opens one up to new details, new possibilities.

Brian Teare is one of my favorite modern poets because his poetry is centered upon Charles Olson’s projective verse and on walking. All his works contain physical coordinates, anchoring each work of art to the place that inspired it. The land becomes the location, subject, and meaning to the thoughts and feelings that Teare wants to convey. As we enter into a field or crest the ridge of a mountain, we perceive the sight of the landscape and experience our bodies within it. We feel the wind and touch the dirt; we see the edges and diversity of the landscape. Perhaps we have hiked a far distance to reach this place and feel the journey within the body. Teare says in one of my favorite poems, “Atlas Peak”:

we have to hold it instead

in our heads & hands

which would seem impossible

except for how we remember

the trail in our feet, calves,

& thighs, our lungs’ thrust

upward; our eyes, which scan

trailside bracken for flowers;

& our minds, which recall

their names as best they can

Sitting on the side of Mount Massive, on the verge of tears, I felt utterly defeated. Our group took the shorter route, which had resulted in thousands of feet of incline in just a few miles, and my lungs, riddled with occasional asthma, were rejecting the task before them. It felt as if all the rocks in the boulder field had been placed upon my chest. My mind went to the thought of wilderness: Was it freedom or a curse? What would happen to me if something went wrong up here? Risk and freedom hold hands with each other in the mountains. After a long break, a few puffs of albuterol, water, and grit, I pulled myself up the final ascent and false summits along the ridge. I have been most thankful for my body when I have realized how beautifully fragile and simultaneously capable it is. On the summit, as we watched thin wispy waves of clouds weave into each other and rise around us, the mountain gently reminded me that I am not in control. I am not all-powerful, and nature’s lesson to me that morning was to respect its wildness.

"Risk and freedom hold hands with each other in the mountains."

As in all things, essentialism should be avoided. We live in a world that tends toward black-and-white perspectives, and when one praises the wilderness, those remarks can devolve into Luddite sentiments that are antipeople, antitechnological, and antihistorical. This solves nothing. Advancements in civilization are welcome and beautiful; technology has connected us in unprecedented ways. But as with anything, balance is key. We need the possibility of escape from civilization, even if we never indulge it. We need it to exist as an antithesis to the stresses of modern society. We need wilderness to serve as a place to realize that we exist in a tenuous balance with the world around us. All the political and societal struggles matter little if we have no environment to live in. In a world of utilitarian decision-making, a walk in the woods may be considered frivolous and useless, but it is necessary. The choice to preserve or to dominate is ours. But before deciding, perhaps one should first wander among the mountains. △

This essay is accompanied by the poem "Post Tenebras Lux" by Haley Littleton.

Scandinavian Inspiration in the Canadian Woods

Villa Boréale by CARGO Architecture