Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Northern Lights Optic × Alex Strohl

Canadian Northern Lights Optic collaborates with French photographer Alex Strohl

Northern Lights Optic collaborates with Madrid-born, French photographer Alex Strohl.

Orion Anthony didn’t just create a product when he launched Northern Lights Optic in 2015. He created a lifestyle.

The brand is championed by its NL-6 and acetate NL-7 glacier glasses—which were inspired by Anthony’s own exploration of British Columbia’s rugged Coast Mountains.

With their lightweight frames, classic circular lenses, and removable leather side shields—the optics pay tribute to the golden age of mountaineering; albeit with a modern twist. These signature models set the tone for the brand.

As an ode to the alpine ways of old, Anthony operates a vintage 1974 Spryte snowcat—a charismatic and unstoppable behemoth, which can often be found parked in the same mountains where the brand was conceived. Anthony works out of those confines (a space that expands into a classic canvas outfitter tent, complete with a wood-burning stove) during the winter—pulling inspiration directly from the elements for which Northern Lights Optic was developed.

It was there at NLO Basecamp where a new vision was born—one that would combine the talents and vision of French photographer Alex Strohl with the alpine heritage lifestyle created by Anthony through Northern Lights Optic. △

Slow Architecture

Spawned by the slow food movement, slow architecture reflects a return to the roots of the master architect tradition

When Italy’s first McDonald’s poised to open in 1986—a stone’s throw from the fabled Spanish Steps in Rome, no less—it ignited not only a protest but a counter-revolution. Italians, so proud and protective of their exquisite centuries-old cuisine and culinary traditions, rebelled against not only the first McDonald’s in their iconic city but the decades of culinary collapse spawned by the “fast-food revolution” of the 1950s—that reduced food, along with its preparation and consumption, to its lowest common denominator. Political activist and journalist Carlo Petrini took part in the initial protest and is credited with the creation of the slow food movement. Three years later, in 1989, the manifesto of the International Slow Food Organization was signed in Paris by delegates from fifteen countries with the goal of promoting local foods and time-honored traditions of gastronomy and food production. It opposed fast food, industrial food production, and globalization, with the goal of preserving traditional and regional cuisine, and encouraging farming of plants, seeds, and livestock characteristic of the local ecosystem.

From slow food came the whole “slow” movement, with slow cities, slow living, slow travel, slow design, and slow architecture—a label credited to the Japanese.

“It is a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better. The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed. Savoring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them. Doing everything as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible. It’s about quality over quantity in everything from work to food to parenting,” writes Carl Honoré in his 2004 book In Praise of Slowness, which has become the new-millennium bible of the movement.

"The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed."

Environmental roots and “deep ecology”

So what is slow architecture? The Tvergastein Hut in the Hallingskarvet massif in Norway epitomizes the concept. It’s a simple wooden mountain cabin in harmony with its surroundings that took several years to build with appropriate, readily available local materials—think small carbon footprint. The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics.

A lifelong mountain climber and Norway’s most famous philosopher and a professor of philosophy at the University of Oslo, Arne Næss was influenced by the writings of seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher Spinoza and twentieth-century ecologist Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, the ground-breaking environmental science book published in 1960. Silent Spring documented pollution from the chemical industry and its detrimental effects on the environment, particularly birds, along with other negative human-caused environmental impacts. The book cartwheeled into scripture for the environmental movement of the 1960s.

Næss was convinced of the impending ecological disaster for planet Earth, and in 1969, he retired from his university position and built his Tvergastein Hut, where he lived and developed the philosophy of “deep ecology,” which sees the complex interconnection and web of all life-forms, objects, and events. Shallow ecology seeks solutions to economic problems through technological fixes; deep ecology demands fundamental economic, political, cultural—and spiritual—changes.

“It’s a whole different perspective of our place on Earth,” says Carolyn Strauss, a California-born, Columbia-educated architect who created the Amsterdam-based slowLab, a research platform for slow knowledge in design thinking and practice. “We work with individuals, architectural firms, architects, and students,” she says. “Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment. And understanding himself as one small part, and not a native of that ecosystem.

“It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things. We’re part of a much larger, complex system, which we can never fully understand. We tend to ignore that fact. And this leads to our fragmentation of the world, versus gestalt thinking—perception of the whole and interdependence. This type of human-centered thinking and fragmentation has generated a lot of the problems in the world,” Strauss says.

“[Arne] Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment....It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things.”

— Carolyn Strauss

Næss’s hut was built from 1937 to 1943, the pieces carried by horse and sled in sixty-two trips up the mountain. He also built a smaller climbing hut on the very edge of a cliff that required one to enter by climbing up through a trapdoor in the floor. Næss and his mountaineer companions climbed and dragged the planks and other materials up the mountain wall to build it. Næss died in 2009 at the age of 96. He lived at his cabin full time—this was no second home.

"The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics."

Spas and churches

On the opposite end of the slow-architecture spectrum is Therme Vals, a hotel/spa complex in Vals, Switzerland, built over the only thermal springs in the Graubünden canton. The architect was Peter Zumthor, who received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2009. Completed from 1993 to 1996, the building is made from stone taken from the mountain, plus concrete and glass. Designed to look like a cave or quarry-like structure, it has a turf roof and resembles the foundations of an archeological site, half buried into the hillside.

The locally quarried Valser quartzite was the driving inspiration for the design, and the building’s cladding is made from 60,000 one-meter-long thin slabs of the greenish-gray stone. Zumthor was fascinated by the mystic qualities of a world of stone within the mountain. He wanted to capture the light and darkness, the light reflections on the water and steam-saturated air, the unique acoustics of the bubbling water in a world of stone, the feeling of warm stones and naked skin—all to enhance the ritual of bathing. So that time would be suspended for those enjoying the baths, Zumthor wanted no clocks in the spa, but three months after the opening, he was pressured to install two small clocks. Zumthor carefully designed a path of circulation to lead bathers to certain predetermined points with areas and views to enjoy along the way. “The meander, as we call it, is a designed negative space between the blocks, a space that connects everything as it flows throughout the entire building, creating a peacefully pulsating rhythm. Moving around this space means making discoveries. You are walking as if in the woods. Everyone there is looking for a path of their own,” Zumthor explains.

A Spanish icon and UNESCO World Heritage Site, Barcelona’s extraterrestrial-looking Sagrada Familia basilica and Roman Catholic church is a classic and very literal example of slow architecture—still under construction 120 years after architect Antoni Gaudi first began it.

Urban and third-world slow architecture

Japan is among the leaders in slow architecture, and a renowned, award-winning example is Hillside Terrace in Tokyo’s trendy Daikanyama neighborhood. This internationally famous residential-commercial complex spanned three decades in its construction and evolution. Its creator, Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, was awarded the Prince of Wales Prize in Urban Design for reflecting the changes of time and giving life to the urban scenery. He also received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1993—a year after completion of Hillside Terrace.

“The flow of time can be measured against its diverse buildings and their relationship to the city of Tokyo as it grew to envelop them,” writes Maki. “The singular sense of place that people strolling among the various buildings and outdoor spaces of Hillside Terrace feel is no accident. It is the result of a deliberate design approach that has created continuous unfolding sequences of spaces and views, taking advantage of the site’s natural topography and, indeed, enhancing it with subtle shifts in the architectural ground plane.”

Butterfly houses

From the Norwegian Alps to the rainy highlands of northern Thailand, the architectural firm TYIN tegnestue, based in Trondheim, Norway, performs humanitarian aid through architecture. Their slogan is “architecture of necessity,” but that still embodies aesthetics. Started by five architect students from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, the firm’s third-world projects are financed by more than sixty Norwegian companies, as well as private contributions. TYIN has worked with planning and constructing small-scale projects in Thailand. “We aim to build strategic projects that can improve the lives for people in difficult situations. Through extensive collaboration with locals, and mutual learning, we hope that our projects can have an impact beyond the physical structures.” The architects use such readily available materials as old tires and locally grown bamboo.

“The Soe Ker Tie House is a blend between local skills and TYIN’s architectural knowledge. Because of their appearance, the buildings were named ‘The Butterfly Houses’ by the Karen workers [an ethnic group from southeast Myanmar]. The most prominent feature is the bamboo weaving technique, which was used on the side and back facades of the houses. The same technique can be found within the construction of the local houses and crafts. All of the bamboo was harvested within a few kilometres of the site,” write the architects on their website, tyinarchitects.com. “The majority of the inhabitants are Karen refugees, many of them children. These were the people we wanted to work for.” The architects hoped to foster a more sustainable building tradition for the Karen people in the future.

Form follows function

“Anybody who is practicing architecture right now, and has been practicing the last thirty years, has seen the profession become so much about style, form-making,” says Colorado architect ml Robles of Studio Points Architecture + Research in Boulder. “Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

“Form follows function,” was the mantra of twentieth-century “starchitect” Louis Sullivan, who admired Henry David Thoreau and Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80–70 BC), who said a structure must be solid, useful, and beautiful. Sullivan’s assistant was Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

— ml Robles

“You don’t start with the box and stuff everything in it,” says Robles, who explains that the three-dimensional modeling computer program SketchUp has become the fast food of architectural design for too many versus careful, thoughtful design.

“So much of what’s happened in the last thirty to forty years was about consumption,” says Robles. “What’s happened is that architecture has become a commodity. So you’ve got, sort of built in, this turnaround—anything that’s a style is going to be out of style...and that’s why we have the crazy environments that we have, and most people are so dissatisfied with their built environments. It’s because they have been designed for a little tiny space in time, with little regard for the past, or really, a long-term future. They’ve been designed for the moment.”

Given all that, Robles says, “Slow architecture, I think, was a pushback to architecture that was about a trend, a pushback to architecture or urban development that was about erasure, and it was a pushback to the commodification of interior finishes and furniture.”

Sustainability and sensibility

The other thing that happened, says Robles, was the sustainability movement, “which was trying to reground the built environment—to be responsible.” So there are LEED buildings, green buildings, and gold buildings. “I think what is happening—and slow architecture is illuminating this—the thoughtfulness of doing what architecture has always been doing is becoming important again. It’s kind of sad that that’s the way the profession has gone.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period. That those things now show up under a label is an interesting reflection of our time, in that we need to be reminded of what architecture is. Those of us who practice architecture in this way have always known.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period."

— ml Robles

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building; you’re in wonder, awe, you’re pulled through the space, usually by light, and you’re changed,” Robles says. “This happens to people when they go into cathedrals. Amazing places where people just, ‘Whoa.’ It happens when you go into a museum, or Union Station downtown in L.A., or Grand Central Station in New York. That’s the essence of slow architecture. What it does to the world. That’s what great architecture does. It causes you to pause and be present.” △

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building...that’s the essence of slow architecture.”

— ml Robles

Geometric Cabins on the Steep

Reiulf Ramstad Architects' Røldal Cabin design preserves as much of the surrounding Norwegian landscape as possible

Anytime an email from Reiulf Ramstad Architects (RRA) shows up in our inbox that mentions the Oslo-based architect and "cabin" in the same sentence, we are all ears. He had us as "preserving the surrounding landscape"... again.

This time, RRA has designed a set of two cabins in Røldal, Norway. Once again, Ramstad's architecture stands simple yet bold. The Røldal family vacation home is recognizable for its compact, defined, and geometric shape. The objective of preserving as much of the surrounding landscape as possible resulted in the design of two volumes: a main cabin (63 square meters; 678 square feet) and a much smaller annex (11 square meters; 118 square feet) that keep a dialogue with the encompassing nature.

Dividing the structures also answers the need for the flexibility of being able to accommodate different family compositions in separate spaces. The articulated section is adapted to the steep terrain and is assigned to create interconnected floors and capture the views of both the forest and the hillside. △

The Grasshopper and the Ant

Winter is coming. A classic poem about preparedness, enjoying life, and friendship.

Monolith on the Mountain

In the Slovenian Alps, Bivak Pavla Kemperla sticks up for alpinists

Bivak Pavla Kemperla, a black beacon for mountaineers in the rugged landscape of the Slovenian Alps, was designed by Slovenian architect and alpinist Miha Kajzelj of the firm MODULAR arhitekti in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Situated at 2104 meters (6903 feet) above sea level in the Kamnik Alps north of Ljubljana, the bivouac under Grintovec was built in 2009 to replace an old shelter that stood there since 1973. The three-level structure is built on a concrete base. The long, vertical windows maximize the magnificent mountain views.

Its outer skin, made of aluminum isolating panels, is designed to prevent loss of the heat produced by the people inside. The inner skin is made of perforated wooden panels designed to wick body moisture out; so the interior always feels dry and warm. As a result of the vertical three-level concept, the upper sleeping level is warm, as the heat from below rises up.

The tiny, simple volume—2 × 3 × 4.5 meters (6.6 x 9.8 x 14.8 feet)—sleeps eight people.

Bivak Pavla Kemperla is dedicated to Pavle Kemperle, a Slovenian alpinist.

Photographer Jaka Bulc (@jakabulc) discovered the bivouac for us with his lens

He writes about his experience:

The first part of the marked trail to this bivouac is usually very crowded, since it leads to a popular mountain hut on the Kokra Saddle and then onwards to Grintovec, one of Slovenia's most frequently visited mountains.

The trail to the bivouac gradually veers off and goes through an interesting passage to a scenic path that winds its way across the steep rocky slopes of Grintovec. We reached the bivouac late in the afternoon and bumped into two other hikers, who were just getting ready to summit a couple of nearby peaks.

The monolithic building gives the impression of being sheltered by the natural amphitheatre of rock walls, although the bivouac sits on a knoll that gently rises over the surrounding landscape. △

The Modern Craftswoman

Crafting small leather goods and wood objects in Boulder, Colorado, Alexa Allen is an artist, a designer, a maker, and a mother

Alexa Allen is an artist, a designer, a maker and a mother. Though not necessarily in that order. It’s more of a constant mash up of all of them, all at once, every minute of the day.

Her story is familiar in the world of design. She started one place, took a few turns, took a few more turns, and today straddles a beautiful line between working for a renowned creative house (i.e., superstar and jeweler to the stars Todd Reed), and launching her latest venture crafting small leather goods and wood objects.

Allen doesn’t turn towards the age-old cliches of “work hard,” “do what you love,” and “follow your dream,” when describing her journey. However, there is no doubt that this woman has put her heart and soul and blood, sweat and tears into creating a thriving business, that right now, after 20 years digging in, is on the cusp of something big.

A conversation with Boulder designer and maker Alexa Allen

Give us the 15 second version of how you landed where you are today

I’m originally from Boulder, and after living in California for many years, moved back to Colorado in 2010 to start a line of eco-modern children’s furniture. While my love for furniture and woodworking remained, I got the creative itch to branch out and learn another craft. I found a leather class by a very talented local leather artisan, and was hooked immediately. I quickly discovered that the combination of wood and leather goods was a natural fit and this realization has shaped my career path ever since.

"While my love for furniture and woodworking remained, I got the creative itch to branch out and learn another craft... I quickly discovered that the combination of wood and leather goods was a natural fit."

What aspect of your upbringing/childhood affected your decision to go into woodworking?

During my childhood, my father was a contractor so I spent a lot of time on construction sites. My father taught me about the tools of his trade—how to hold them correctly, how to use them, and how to take care of them. I spent endless hours trying to master the art of hammering a nail all the way in with one hit. I never did master that one. However, I’m sure I was one of the only girls in third grade who could wield a hammer, and I took great pride in it. Looking back, my career as a craftswoman makes complete sense though, truth be told, as a girl, I never envisioned that I would earn a living doing so.

"Looking back, my career as a craftswoman makes complete sense."

Describe the moment you decided to become a craftswoman

I earned a bachelor of arts degree in art history from Scripps College in Claremont, California. Scripps is an esteemed women’s college, and in addition to providing me with a great foundation in the arts, it also gave me the strength and confidence to succeed as an independent woman.

After my time at Scripps ended, I realized that interpreting and assessing the art of others was not my ultimate purpose in life. I wanted to create art of my own. As I contemplated which direction to take, it soon became clear that I needed to practice an art form that was physical and hands on. Thus, I enrolled in the furniture design department at The California College for the Arts (CCA). For me, the act of making/building/creating must engage both my mind and body—the physical act of making is a crucial component of my art.

"Scripps is an esteemed women’s college... it also gave me the strength and confidence to succeed as an independent woman."

Furniture-making has now evolved into leatherwork and I am excited to see where it takes me next. The more I learn, the more passionate I become and the more my creativity grows. This thirst for new skills is the driving force in my work. By continuing to learn and expand my skills, I can confidently call myself a designer, an artist and a craftswoman.

"By continuing to learn and expand my skills, I can confidently call myself a designer, an artist and a craftswoman."

What is the one piece of advice you would give to young women who are just getting started?

I was fresh out of art school at the California College for the Arts when I was hired at a custom cabinet shop in Oakland. The furniture department at CCA had a fairly large number of women in the program and we had an amazing camaraderie. It never occurred to me that this would not be the case in a “real life” scenario.

I was hired at the woodshop in the middle of a high-end Japanese-inspired project, which required a lot of skilled, on-site work. I was called on to route a 12-inch circle that needed to precisely fit a metal fixture, which had just been laid. I was stressed—one small slip of the router or one mistake in sizing, and I would have set the project back by weeks.

I made a jig and practiced in the shop, until it was perfect. The day I walked on site, there were five drywall guys all staring at me. I walked in and set up my router and my jig. By the time I had finished setting up the entire construction crew was watching my every move. I was so nervous! But, I knew what I was doing and I confident in my abilities. Needless to say I executed the task perfectly and from that day on, I was known as “the router queen.”

So my advice to women out there who are just getting started? Know your shit and walk in there like you own the place. △

This story was originally published by TARRA: Women Who Create

Snow-Proofed Hillside Family Home in Austria

This house can weather even the fiercest winter storm and an avalanche

Most homeowners would avoid living within striking distance of an avalanche, but Marcell Strolz and Uli Alber embrace alpine extremes. They built a house that could weather even the fiercest storm.

Most homeowners would avoid living within striking distance of an avalanche, but Marcell Strolz and Uli Alber embrace alpine extremes. They built a house that could weather even the fiercest storm.

With its world-class skiing and picturesque alpine setting, the Austrian village of Lech seems ripe to become a buzzing tourist destination. But due to strict regulations against second homes and a high risk of winter avalanches, very little building takes place in this small community. Marcell Strolz and Uli Alber were aware of these limitations when they set out to build a family home, and they knew their modern tastes might be contentious in the slow-changing town. The site they chose at the edge of the village afforded them creative freedom with one inherent condition: The house would have to withstand the forceful blows of sliding snow.

Land slope-side

“It is very difficult to get land here for building,” says Strolz. “Beyond us is a pasture where there will never be any other homes.” Having grown up in Lech and having spent many winters volunteering in avalanche protection, Strolz, who works year-round as a project manager for engineering and building contracts around the village, was ready to live a stone’s throw from the ski runs. He and his wife, Uli, a physical therapist and sports trainer, took preparedness seriously as they designed a place to live with their young children, Felix and Emilia.

“We used some steelwork in addition to the timber frame to strengthen the house,” says Strolz. “A series of sliding wooden shutters protects the building, as does specially strengthened glass around the kitchen.” These shutters can be closed off to seal the windows against avalanches or during the annual “snow roll” fromthe nearby Omesberg mountain, when a controlled explosion shoots snow downhill past the house. There is also a retractable wooden wall, which disappears into the floor, to protect the open veranda.

Sustainably designed by Helmut Dietrich

The house was designed by Helmut Dietrich of Dietrich Untertrifaller Architekten, an Austrian practice known for its sustainable and sensitive approach to design. “It was very important to all of us that the house have a relationship to the mountains rather than other buildings,” says Dietrich. “It was the connections with nature—and framing the views—that interested me most. It was also important to us to be able to use timber construction, despite the avalanche risks.”

“It was very important to all of us that the house have a relationship to the mountains rather than other buildings."

Strolz worked closely with Dietrich throughout the design process, and he managed and participated in the building’s construction. “I got very involved in the preparation of the site, the digging of the foundations, and the concrete base of the house,” he says. “The wooden frame was prefabricated by a local construction company and went up in two days. I also did the drywalling, the floors, some of the electrical—it was quite a lot of work.”

Flexible for family living

Flexibility was a key part of the design. Two separate apartments—one for rental and one for a nanny—are integrated into the building alongside the family’s two-story space. The main living area has an open plan leading out to the veranda, with bedrooms and a study on the floor above. All of the timber for the frame and cladding was sourced from sustainably managed forests.

On the roof, Strolz installed solar panels, which are cleared of snow during the winter so that they can function year-round. “The house holds heat very well,” he says. In the summer, excess heat is mitigated through natural cross-ventilation. The shutters that protect the windows from damage double as sun shades, and some rooms of the house have additional internal blinds.

“Most of the new houses in the region address sustainability,” says Dietrich. “In Marcell’s case it was particularly important because of the climate in Lech, where there are long winters with cold temperatures. The house had to cope with the climate while using as little energy as possible.”

"The house had to cope with the climate while using as little energy as possible.”

Their power strategy was supported by one of Strolz’s earlier projects, the construction of a biomass plant for the town of Lech, which was completed ten years ago. Designed by architect Hermann Kaufmann, the plant is sited in a sleek timber-clad building on the road into the village. Its large industrial boilers supply heat and hot water to homes throughout the village.

Progressive architecture in Vorarlberg

The Strolz house is unusual in this rather conservative community, and some compromises were required in order to get the plans approved. “At first, I was told that the house was too long and too high and that the shape of the roof was wrong,” says Strolz.

“So we redesigned it to a certain point and then they said yes.” Despite the changes, the house sits well within the progressive architecture of the Vorarlberg region as a whole, which is famous for its approach to modern design.

When the weather is fair and the shades are open, one would never know that this graceful house is capable of becoming a fortress. The light-filled building and stretches of open space beyond are ideal places for the kids to play. But when cold weather comes, the family takes comfort in a design that keeps them safe, even if the mountains shake loose a season’s worth of snow. △

Wild Presence

Outdoor and wildlife photographer Martin Dellicour captures the graceful lure of chamois and ibexes in the Italian Alps

Early last winter, Belgian outdoor and wildlife photographer Martin Dellicour overnighted in an old barn in the Italian Alps to wake up among these wild yet graceful chamois and ibexes.

Backcountry Haven

Professional snowboarders modernize a run-down cabin in Utah to access untracked powder out the front door

Professional backcountry snowboarders Zach and Cindi Lou Grant modernize a run-down A-frame cabin outside of Park City, Utah, to help them access untracked powder and follow their dreams.

They spent as much time as possible up in the Wasatch Mountains east of Salt Lake City, Utah, and only came down for school, work, and sleep. Zach and Cindi Lou live for snowboarding, so it was only natural for them to buy their own alpine cabin to be as close as possible to their favorite backcountry terrain near Park City. Surrounded by snow six months of the year, their newly renovated cabin lets the pair follow their dreams and snowboard much of the year.

Backcountry education

After high school, Zach and Cindi Lou rented a small A-frame cabin in Big Cottonwood Canyon to be in the mountains. For the last decade, the couple has been honing their skills, taking avalanche safety courses, and learning all there is to know about backcountry snowboarding. They use special snowboards, called splitboards, which separate into two boards to allow for uphill travel. When they get to the top, they put the two halves together, spin the bindings to make it like a normal board, then click in to ride down. Safety is their number-one priority, though, and they work together as a team to ensure that at the end of the day they both get home in one piece.

Over the years, the partners have gone on great adventures in Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and Alaska. They have been featured in ski and snowboard magazines and movies, like Powderwhore Productions’ Some Thing Else. Their years of touring in the backcountry together only improved their relationship, and in 2011, the two got married. Soon, sponsors including Voilé, Smith Optics, and Gregory Mountain Products picked up the pair as team riders, turning their dreams of becoming professional backcountry splitboarders into a reality.

Finding heaven in the backcountry

All the while the two knew they wanted a cabin of their very own from which to base their adventures. After searching for a couple of years, they found a run-down A-frame on the Wasatch Back in the Rocky Mountains of Utah that was within their budget. It was a fixer-upper, with the cabin barely standing, but on the plus side, it had great backcountry terrain close by and was just minutes outside of Park City.

Technically, the cabin is located in Midway, but it’s closer to Park City. With all the snow in that area, they need a snowmobile to get back and forth during the winter. “It feels like you’re away from everything, but you’re really close to town,” says Zach. “The quality of living back here is top-notch. It’s so quiet and peaceful, and it’s really cool to be able to ski in and ski out.” Situated in a small valley, the cabin has a small seasonal stream running alongside it, enjoys full sun throughout the day, and also has great views of the mountains, aspen groves, and lots of wildlife nearby.

Building dreams

Unfortunately, what they thought would be a simple matter of some new insulation, plumbing, and sheetrock turned into a much bigger project. “It was like pulling a string on a sweater,” explains Cindi Lou. “Once we started, the whole thing just began to unravel.” After seeing holes in the roof and all the shoddy construction, they realized they would basically have to tear down almost everything.

Over the course of two years, with a lot of help from family and friends, the couple reconstructed and renovated their cabin, turning it into an open, 1,800-square-foot home. The previous owners had jacked up the original A-frame onto a taller foundation, added storage rooms underneath, and tacked on an addition to the north. Zach and Cindi Lou left the ground floor and the addition, but made them more structurally sound and weatherproof.

They tore down the A-frame structure and built a new space with straight walls and a south-sloping roof that mirrors the roof on the north addition. This transformation turned the home into a modern cabin and allowed for straight walls and more space inside while keeping the same footprint. The old roofing material was reused as the exterior cladding, giving it a rustic yet industrial look reminiscent of the old silver mines nearby.

Spray foam insulation helps create a tight, high-performance exterior to keep the home warmer. New energy-efficient windows bring in plentiful natural light so they don’t need to turn on lights during the day. “All the windows are definitely my favorite thing,” says Cindi Lou. “I love to look at the stars from my bed at night.”

“I love to look at the stars from my bed at night.”

Inside, the first floor has a large open-floor-plan kitchen and dining room, with the living room inside the original north section. Lofted above the bathroom, their bedroom’s tongue-and-groove wood paneling on walls and ceiling offers a warm and bright interior. Family heirlooms and vintage furniture fill the space, while giant black-and-white pictures of Zach and Cindi Lou snowboarding—a housewarming gift from Voilé— adorn their walls.

On the ground floor, an extra living space snugly surrounds a large woodstove that heats the entire home in the winter. Also downstairs are the laundry room and the couple’s gear-filled room of snowboards, boots, outerwear, camping gear, and biking, climbing, and shing gear for their summertime sports.

Living the dream

As it goes with most DIY homes, Zach and Cindi Lou’s cabin isn’t complete yet. It takes time to remodel a house, especially when you’re as dedicated to your passions as this couple is. Not to mention, they both have normal jobs in Park City that keep them busy. In the winter, Zach works as a snowcat operator at a local resort grooming ski runs, and in the summer, he switches to trail maintenance. Cindi Lou teaches yoga at Park City Yoga Adventures and buys gear for the local White Pine Touring shop.

In winter, they focus on splitboarding and being in the backcountry as many days as they can. In summer, they buckle down to work on their house, trying to complete whatever projects they can before the snow falls again. This next year, they plan to tile the kitchen and focus on finishing the downstairs, tricking out the gear room, and adding a second bathroom for guests. Eventually, they hope to add a photovoltaic system to take advantage of their great southern aspect.

The two have put a lot of hard work into their home, but say it’s all been worth it, plus a great learning experience. “It’s really rewarding now that it’s our own,” Zach says. “But I was surprised at what we were capable of.” Despite some real challenges, like building the water system or installing the roof rafters with a makeshift pulley system, the two got it done together and built their own backcountry heaven. Because working as a team, whether in the backcountry while snowboarding or renovating their cabin, is what the Grants do best. △

Louis Joseph on Alpine Authenticity and an Old Sweater

An uplifting conversation with the founder of the Boston-based outdoor garment label Alps & Meters

Nostalgic and progressively technical at once, the rare outerwear garments of Boston-based Alps & Meters reflect an appreciation for the authentic alpine adventures founder Louis Joseph has experienced in mountain villages around the world.

AM Your idea to start a performance outerwear brand was inspired by a trip to Sweden and a vintage ski sweater. What’s the birth story of Alps & Meters?

LJ I’ve always been an alpine sports enthusiast, primarily skiing, and I’ve traveled the world to places near and far for it. I was on a trip to Sweden—could be as many as fifteen years ago now—and I bought a vintage knit ski sweater with very interesting technical attributes. Ever since that time, the garment traveled with me wherever I went. It became a significant conversation starter in places like New Zealand, the Rocky Mountains, Europe. I let a lot of these conversations wash over me and started to think more deeply about what was so interesting and appealing about that particular piece. That was probably the springboard for Alps & Meters, trying to understand what people responded to, from the romantic nature of that piece to its technical attributes, these beautiful, rich knitted fibers, which is a bit of an art now that is lost and forgotten. That sweater transports you to a different time and place, perhaps a little simpler. There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand.

"There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand."

AM Years of research and travel went into your product creation, until you finally found the right materials and manufacturers...

LJ Yes, I am probably five years into Alps & Meters now, since it was a spark of an idea in my mind. I took many trips to a lot of different destinations, here in the United States and in Asia, to find a factory that would work with a new brand, not only a small brand, but also try to innovate and create a different expression of performance outerwear. We came up with a product-creation philosophy that we call “forged performance.” It’s a marriage of classic garment construction techniques with natural materials, like whole-grain, water-repellent leathers and nano-coated yarns, and bundling that together with contemporary technology. Many factories found the complexity too difficult to digest. I ultimately found a family-owned company in Taiwan that has been knitting garments in a very sophisticated way for decades.

I was global director of strategy and innovation at Puma and actually moved to its headquarters in Germany. I left that job a couple of years ago, turned our website on to gauge a demand for the concept, and here we are.

AM What does your brand name—Alps & Meters—represent?

LJ We wanted to convey a sense of tradition and a classic appreciation for authentic alpine sports. Obviously, the Alps came to mind in terms of all their transportational values, and this very traditional, true atmosphere. The word meters has a double meaning within the context of our brand: meters not only in terms of height and the expansiveness of mountains and ranges, but meters is also the unit of measurement for tailors. We wanted to have that underlying meaning closely connected to the brand, because we are really trying to refine our garments and express a form of outerwear that’s very meticulous in terms of attention to detail and the materials we are using. This unit of measure helps us to think very creatively of tailoring the pieces in a manner that is not only differentiated but still provides first-class, on-mountain fit and protection. I always think of the old tailors’ measuring tape, that really rich, yellowed meter tape. And we love the ampersand in the brand name. “Alps & Meters” has a bit of an old-world family feeling to it that I think is nice and sturdy.

AM What makes you a mountain man at heart?

LJ I grew up skiing, primarily in the United States, and I fell in love with the sport— not only the sport’s individual aspect of being on your own in the mountains and having that quiet and connection to nature, but there was always a camaraderie and a friendliness about the places that I traveled to, where people can affiliate and relate, whether they are in Japan, Europe, South America. It always struck me that that same sensibility was shared and crossed generations. Before I got married, I spent a lot of my money on a couple of interesting ski adventures. I’ve skied in the summer, too. I’ve been to Argentina, and I’ve made my way to Chile. I always appreciated connecting with new cultures, primarily in mountain settings, and those simple double-chairlift rides, meeting somebody new, from a different background, a different place, speaking a different language.

It actually has always been a rite of passage and a tradition for the Alps & Meters team to ski a glacier at the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range. It’s about a four-hour hike with full pack, boots, skis. You start below the tree line, and all of a sudden you are in a snowy environment.

AM You have a deep connection to Vermont. Why did you open your office in Boston?

LJ My wife and I got married two years ago at a beautiful inn in Vermont. Much of the concept for Alps & Meters was born from ski trips to Vermont, sitting outside around a fire, snow falling, talking with staff who are avid skiers and alpine enthusiasts. We’ve tried a virtual headquarters in Vermont for some time, but the logistics were really challenging. Alps & Meters has deep roots here, but our team is now settling down in Boston, which is wonderful for logistical purposes, travel to Europe, shipping is very easy.

AM You strive for authenticity. How does this intent translate into your brand?

LJ There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else. That is something I love about European skiing, a timelessness and authenticity that crosses generations. It’s wonderful to hike the same trail, ski the same routes, or ride the same lift somebody had done fifty years ago.

At Alps & Meters, we are trying to express a very deep appreciation for classic alpine tradition, and that expression is obviously manifested in the products we are creating. The materials we are exploring are authentic. They are tried and true.

They have always stood the test of time. There are performance characteristics, but their aesthetic is very authentic, and they are a recall to that authentic experience. There is a great confidence in entities that are authentic, and they have a real gravity that can be felt. I’ve been to Chamonix, for example, and it just resonates with authenticity—the people, their respect for the mountains, how they treat one another. It’s one of those very difficult feelings to describe, but you know it when you see it.

“There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else.”

AM You launched Alps & Meters with a small collection of three pieces. Talk about your flagship product, the men’s shawl-collar jacket.

LJ We are really trying to make a statement with this shawl-collar jacket and keep our exposure low in terms of the breadth of the product collection. The shawl-collar jacket is a very nostalgic piece from the perspective that it is actually a properly knitted garment. In today’s menswear world, there aren’t many factories or brands that are actually knitting goods. We wanted to revisit proper knitwear that’s protective, warm, has great range of motion and ergonomics, and apply that to an outerwear garment that has a contemporary stance. That type of classic garment construction technique was actually the first wind stopper. You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today. Leather is another material we feel has a very timeless nature. What’s special about that versus synthetics is that leather has always been used for maximum durability. It’s still probably one of the most durable materials you can find and apply if you are looking for garment reinforcement and protection. But what we find really intriguing is leather will wear in; it will take on patina in color, and nicks and scratches will become a memory keeper. You remember when the garment was marked a certain way, on a certain adventure.

“You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today.”

We have since evolved, and we have six or seven pieces, including a beautiful alpine winter trouser this coming winter. In our next collection, we are also modeling an alpine anorak, a pullover, on a piece that was used by the 10th Mountain Division as a protective snow garment. We are making that from a British-milled impregnated, waxed cotton. It’s windproof, it’s water repellent, and it intrigued us from a performance point of view. Again, I’m surprised that such a highly durable, tactile, beautiful material that will also have interesting wear characteristics wasn’t being used in performance outerwear.

AM Your outerwear may evoke nostalgia in the older generation while appealing to younger winter sport enthusiasts for its performance aspects. Who is your target audience?

LJ When I was traveling in my old Swedish knitwear piece, the age range of individuals who felt my sleeve in the lift line or asked me about that piece was very diverse. We are still trying to learn where the intersection is of our forged-performance differentiation and the interest level, whether it is rational or emotional or a combination therein. We are feeling our way through the dark but are really trying to stay true to what we believe, which is a respect and appreciation for simple, timeless alpine tradition.

Personal Brief: Louis Joseph

Born

1973 in Santa Monica, California

Then What?

After a stint in California, my family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, then settled in Boston, Massachusetts— fittingly, during the Blizzard of 1978. I began skiing in the mountains of New England from a very young age. My earliest years on the slopes were spent in North Conway, New Hampshire, at mountains such as Cannon, Attitash, Cranmore, and Wildcat.

In my post-university years, I gravitated toward telemark skiing after having been intimately introduced to the tradition by a close Italian friend from the Dolomites of Italy.

Now Lives

Boston, Massachusetts, in a quaint area called the South End, a walkable, friendly neighborhood of side- walk restaurants, pubs, and coffee shops.

Lives With

I live with my wife, Vinita. She is my best friend and an adventurous spirit who shares my passion for the mountains and any sort of outdoor recreation.

Favorite Place in the World

My favorite place is to be fireside in an après-ski setting. I find no greater joy than exhausting myself skiing with friends and family and then reliving that shared experience through storytelling, a crackling fire, and the satisfaction that comes with a day well spent on the mountain.

Next Big Journey

My wife is Indian, and we hope to visit India together sometime over the course of the next eighteen months. One of our dreams for this trip is to extend the adventure to Nepal and visit the base camp of Mount Everest.

Life Philosophy

Philosophically, I’m hopeful that I am leading a life in which I have my eyes open to new experiences, a sense of adventure, stay firmly grounded with humble perspective, and express a constant thankfulness for the opportunities afforded me while being kind, considerate, and helpful to those less fortunate.

Favorite Piece of Clothing

I appreciate clothes and equipment that are timeless in their utility and presentation. Therefore, my favorite piece of clothing is my father’s official U.S.-issued peacoat, which he wore while serving in the Coast Guard in the 1950s. Made from heavy boiled wool with a uniquely high collar, this jacket’s cut and sewn simplicity belies a warmth, durability, and protective nature that rivals contemporary outerwear of today. It’s also a powerful memory keeper as my father’s name, military company, initials, and year of issue are scratched on the interior in indelible chalk. When I’m not wearing my Alps & Meters shawl collar jacket, my father’s peacoat keeps me timelessly stylish and warm because of its deep family connection.

Inspired By

My mother and father have been my greatest influence and have been a well of inspiration to me throughout my life. My father is a first-generation American who instilled in me a strong work ethic and a “can-do” mentality. My mother is full of humor, mischief, and adventure, and I thank her every day for teaching me to ski. Their combination of values, imagination, and powerful encouragement have inspired me to follow my passions and, without a doubt, set me on a trajectory to explore, create, and launch Alps & Meters. △

Title photo by Torkil Stavdal

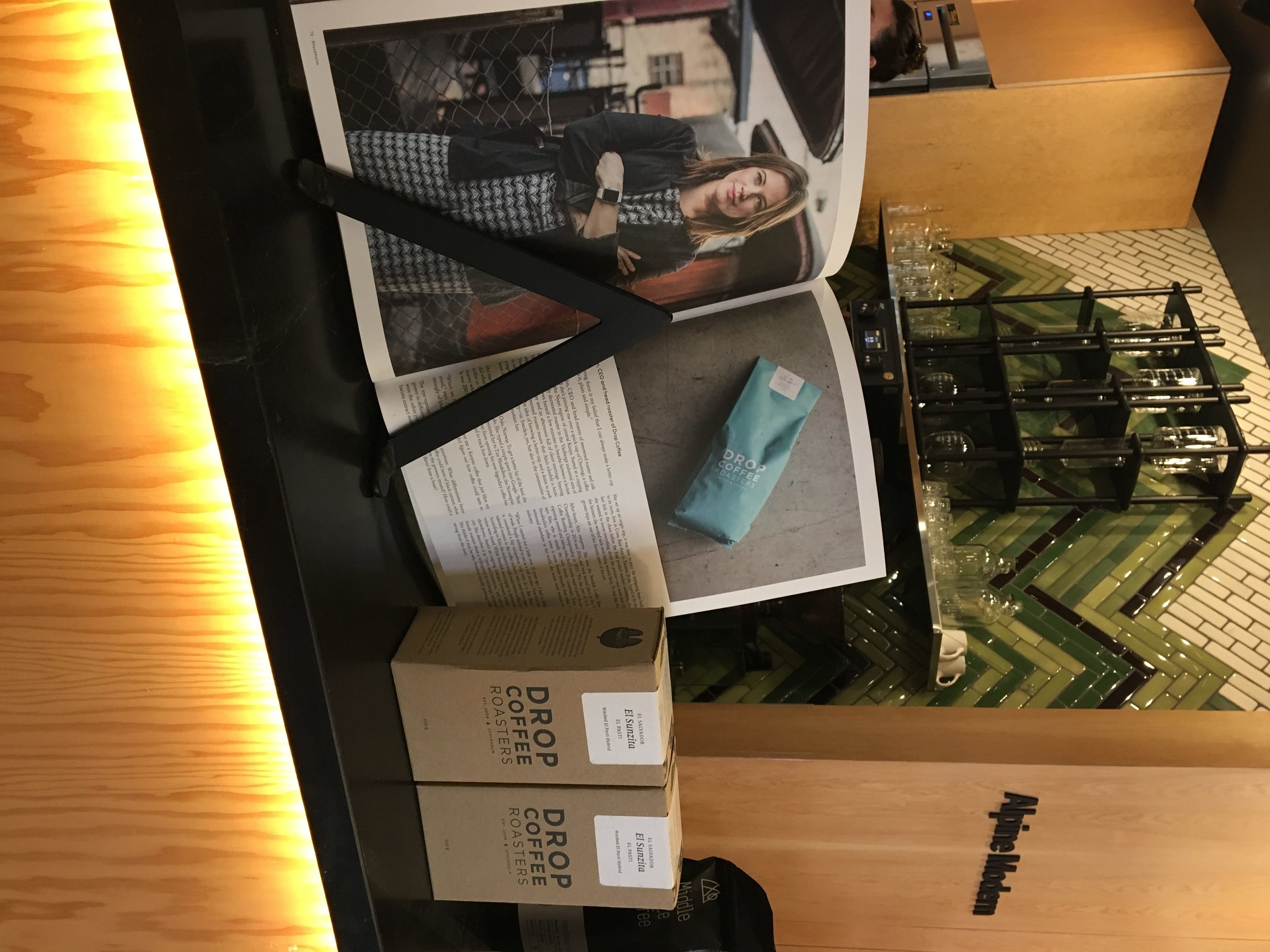

Drop Coffee at Alpine Modern

We debut our new monthly guest roasters program with a revered household name from Sweden

At Alpine Modern, in our effort to give our community access to high-quality and interesting coffees, we have begun a monthly guest roaster program. While still consistently serving single-origin and blend offerings from MiddleState Coffee on espresso and drip, we will bring in a new roaster each month to offer variety to our customers in our batch brew coffee. We will also be selling whole bean packages of the coffees.

Stockholm’s Drop Coffee

We debut with Drop Coffee as a unique opportunity to taste an extremely high-quality and long-sought-after roaster and bean.

For coffee aficionados, the Swedish roaster Drop Coffee has been a revered household name. The chance to visit the famous roaster and take classes in Stockholm is considered a sort of pilgrimage for the dedicated barista.

The company started in 2009 and quickly became a leader in the specialty coffee world. Using a direct trade model, the roaster mainly sources from Bolivia, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Ethiopia, and Kenya. For several years, Drop has won Sweden’s Roasting Championship and has placed in the top five at the World Roasting Championship since 2014. Sourcing from green-coffee importer Nordic Approach, started by the well-known Morton Wennergaard and Tim Wendelboe, Drop receives some of the highest-rated varietals currently in production.

In an interview with Kinfolk, Joanna Alm, co-owner and head roaster, outlined Drop’s coffee philosophy:

“We strive to bring out all the good natural flavors of the coffee in the roasting process without adding any roast tones. It’s crucial for us to keep all the natural flavor of the coffee throughout each step of the production chain, from the cherry to the final cup, regardless of the brew method. This is a bit controversial on the coffee market, but it’s the only way to achieve our aim to get most out of the product.”

"It’s crucial for us to keep all the natural flavor of the coffee throughout each step of the production chain, from the cherry to the final cup, regardless of the brew method."

The Coffee: El Sunset

The coffee, El Sunzita from El Salvador, is a Bourbon hybrid called “hybrid El Pasti” that comes from the farm of Mauricio and Mary Ortiz in the growing region of El Pasti.

Joanna Alm writes on the Drop Coffee website:

”El Sunzita is a great example of driven producers who are putting in the extra work to higher the quality Mauricio Ortiz and Mary Ortiz are looking at their microclimate and trying to work the most organic they can in an area suffering hard from leafrust. The location of the farm and the view is something else and one of the most beautiful farms I’ve visited.”

“Bourbon” is a coffee varietal that was brought from the Indian Ocean island of Bourbon (Reunion) in the early nineteenth century and was transplanted in Brazil, Central and South America, and Rwanda. It soon grew popular because of its ability to produce quickly and efficiently. El Salvador, in particular, is known for the varietal that offers toffee and caramelized notes. The Ortiz’s Sunzita is a special hybrid of the Bourbon varietal and makes up about 65% of the farm that sits in Santa Ana at 4,000 feet (ca. 1220 meters).

The coffee is fully washed; meaning all the pulp surrounding the bean is cleared away, leaving a clean, bright cup of coffee with very little inconsistencies. El Sunzita has a medium body with notes of raisin, chocolate, and dark cherries.

The high quality of the bean is mirrored in the sleekness of the packaging design. 250 grams are sealed in an airtight plastic re-sealable package and placed inside a small tan box that features an intricate line-work drawing of a coffee cherry and plant. Alpine Modern is selling these limited edition packages for $20 each.

For the rest of October, come by the Alpine Modern Café at 9th and College in Boulder or our new Alpine Modern Shop + Coffee Bar at Pearl West to sample El Sunzita on our Curtis batch brewers or take home a bag of this sought-after coffee. △

Makers on Board

Born out of passion for the ride, handcrafted snowboards, splitboards, and skis by Vancouver Island's Kindred Snowboards feature marquetry artwork.

Kindred Snowboards was born out of passion for the ride and the opportunity to grab a snowboard press off Craigslist. Meet the spirited couple who handcrafts custom snowboards, splitboards, and skis featuring marquetry artwork on Vancouver Island.

Evan Fair and Angie Farquharson have been designing and making custom snowboards and skis together in their backyard woodshop on Vancouver Island since 2010. We squeeze in a weekend visit just before the busy winter season to get a glimpse into their craft, their art, and their humble lifestyle in a rural community on the island’s east side. The couple built the Kindred Snowboards brand from scratch. They cultivated the low-impact operation out of nothing more than a passion for the ride and the desire to make a higher-quality product—yet without any background in fabrication.

Beautiful Comox Valley and Mount Washington straddle this area fifteen miles (twenty-four kilometers) north of Courtenay, British Columbia, where their home and shop are located. Weather on the east side of the island is mild and temperate year-round, a surprise given the substantial annual snowfall in the nearby mountains. The couple’s home sits at sea level in a forest, the mountains hidden from view. Land plots are large here, spreading neighbors apart. Industry in this area is a miscellany, though mostly milling timber and small-batch farming. Neighborhood homesteading makes the community largely self-sufficient—the local crops and dairy products go directly to the local population.

Pressed to jump

“How is a snowboard made?” the couple, both in their late twenties, asked each other one day before it all began. Not long after they pondered the process it may take to create the boards their life revolves around, a snowboard press came for sale on Craigslist. Fair and Farquharson, as adventurous as they are curious, grasped the opportunity. At the time, they were living out of a camper van and chasing the best snow to ride. But they made the purchase, hoping the investment would be the impetus to launch them into a more serious endeavor.

They were committed. Being avid riders themselves, they knew exactly what they wanted in a board, what their ideal board would look like, feel like. So they learned and improved upon the techniques to make a better product. Their goal was to create high-performance boards and skis that enhance, not hamper, the user’s skill, style, and fun on the snow.

“Some experienced riders know exactly what they want, down to the numbers,” Farquharson says. With others, the Canadian gear artisans spend significant time getting to know the customer’s riding style and preferences. “For the topsheet artwork the questions are a bit more ephemeral,” she says. People have asked for anything from the silhouettes of their favorite mountain to portraits of their pets or pop-culture idol, and even memorials to lost loved ones. Kindred’s Limited Edition Series, on the other hand, features artwork infused with an alpine or coastal sensibility. “I draw from my own personal experiences in nature, as it is common ground for people who spend their recreation time outdoors,” Farquharson says.

“For most people the way their gear looks is a very close second to how it rides,” she knows from experience. “People who go for a custom build impact the end product directly, which can be empowering. The ride becomes a distilled reflection of the rider and what they want out of their alpine experiences. In the end, Evan and I hope our work inspires people to be themselves and to be better riders.”

“People who go for a custom build impact the end product directly, which can be empowering.”

Shop talk

That mission to make a superior board hasn’t shifted or been compromised in the five years since Kindred began. Each board is treated with the same intense amount of care and precision. Personal connection with each customer and hands-on craftsmanship that goes into every board leave the couple remembering almost every individual product. The number of orders Kindred fulfills has been growing every year. By the end of this season, they are projecting to have made approximately 150 boards, splits, and skis.

Their search for the right place for Kindred led the couple to a tree-lined rural spot with a woodshop, old smokehouse, and former boathouse turned into a woodshed. They purchased the property with the intent to grow their business and live in the same place. “At first, we considered commercial property around the area, but it made more sense to have a shop very close to home,” says Fair. “The former owner was a cabinetmaker, so the shop already existed and was set up for woodworking.”

"Personal connection with each customer and hands-on craftsmanship with every board they make leave Fair and Farquharson remembering almost every individual product."

Sunlight filters into the shop through the grapevines that walk along the top of the awnings and the edge of the roof. As the gentle breeze blows, the leaves dance in the wind, making the patches of light dance on the floor. The view from the workshop doors is still lush and green this time of year; an occasional chicken races by or stops to graze for bugs in the grass. Inside, the walls are neatly laced with deliberately arranged hand tools and jars of screws and nails hanging from lids nailed to the shelves, organized according to the makers’ workflow. Fair’s homemade shelves display boards and skis in progress. It’s obvious the two designed this workshop with careful thought.

Fair puts on an album by Little Feat as the machines are slowly starting up. All of us pull on protective face masks before he begins sanding the core of a board he prepped the night before.

Meanwhile, at the giant table in the back of the shop, Farquharson sets up the topsheet, the piece that is most visibly “Kindred” to those familiar with the distinctive snowboards. The topsheet, a thin wood veneer, is intricately designed. The decorative patterns and graphics are meticulously cut from different woods and inlaid using a technique called marquetry. Defined by the grain and color of the woods, the outline of a fir tree begins to show light and definition in its branches, and a moon shows its craters. This detailed, time-intensive process makes Kindred boards one-of-a-kind art pieces.

Farquharson cuts the wood with her penknife. We talk about Kindred’s customer base as she carves out a moon from a delicate sheet of gorgeous black walnut.

“We’ve had incredibly strong local support from shops and individuals, but we are fortunate to ship all around the world,” she says. “We even had a Japanese fellow arrive unannounced from the other side of the world who had planned his whole vacation around watching our build process...He is now a friend of ours.”

Return to the Valley

Fair sets up a bottom sheet to be cut with a drag knife mounted to a CNC machine (computer numerical control machine, or automated milling machine used to make industrial components). He tinkers with the calibration on a laptop next to it. Satisfied, he hits “start” and the knife begins to cut out the Kindred logo from the sheet. When I ask him about their initial business ideas and how things have developed through the years, he pauses. “Humble beginnings for sure,” he replies.

“The concept was founded while we were living in a truck and camper. We had left the island to travel throughout Alberta and BC looking for the next ski resort. When we decided to embark upon the snowboard-building adventure, we returned to the Comox Valley, where we already had a network of support. We initially saw a potential niche in building high-quality North American skis and snowboards, and quality and beauty remain central to every step of the process—no cutting corners.”

A complex custom build can take the two up to thirty work hours to design and build a board or a pair of skis, not counting drying and curing time. The Limited Edition Series builds, where Kindred makes a small number of products with similar designs, still take up to fifteen hours each.

The day goes by quickly, and before we know it, the afternoon sun starts to set. The board is ready for the nal press, and all the layers are assembled with a chemical-free epoxy slathered on between each layer as the machine applies a healthy dose of heat and pressure. It’s fascinating to watch the steel tube stock apply pressure, making the epoxy ooze out the sides, slowly creating mountains on the floor. The snowboard press that started the whole operation is beautiful in its frugality—a testament to Kindred’s mindset.

"We initially saw a potential niche in building high-quality North American skis and snowboards, and quality and beauty remain central to every step of the process—no cutting corners.”

Community board

A couple of miles from the workshop, a local mill saws logs into lumber for the core pieces, the main foundation and center of each board, sandwiched between layers of fiberglass and carbon fiber. Farquharson and Fair know the owners of the mill well, and the family’s son is out working when we visit. With a population this small there is a strong reliance on others and an understanding that you are a connected member of the island community. Your actions greatly impact the local environment and its residents. Thus, good relationships with neighbors are important for businesses like Kindred to thrive.

As we observe the milling, Fair steps in to help move the last few logs on the run. “Many people are here for recreation—not specifically to ski or snowboard—they come to enjoy a work-life balance and the mild climate, fostering a slower pace overall,” he tells us.

What’s in a name?

How did the name “Kindred” originate? “We wanted to recognize how constantly blown away we are by the support of our community, friends, and family,” says Farquharson. “On another level, we give homage to the incredible relationships that are forged through alpine winter sports and lifestyle. Nothing quite compares to charging through fresh snow engulfed by the euphoric hoots and hollers of your friends. Those snowy moments, when we’re living a shared experience, feel like pure magic. When you are surrounded by people who embody that joy on and off the snow, you can’t help but feel like family. Those are our people. Kindred felt genuine and accessible, as we were sure that other skiers and snowboarders could relate.” △

Earthbeats

"The mountains speak in an unlearned language that I love."

All I’ve known to cure myself is this— Blue and green hues pulse together while I’m lying lonely on top of pine needles. Rows and rows of trees with peeling, orangey skin align, and the symmetry feels safe. It’s nearly sundown, and the whirring noises are far away in the city. All I can hear is clarity and crickets.

Colorado is my home now.

The tree bark is my creative chair. My brown leather journal lies in my lap, but I don’t know where to start, or which questions to ask that I haven’t written down yet.

The wind touches my skin, and breath branches into all parts of my body in bold colors.

Most of my thoughts reflect the relationship we have to the earth. I’ve realized how feeble my body has always been at such a young age, filled with air and always wanting something looming overhead. The mountains move me further from feeling like I need answers. The mountains speak in an unlearned language that I love.

I close my eyes and slide farther down onto the ground.

Land cradles my body, comforting me like the child I crave to stay. Returning to the roots of existence and feeling the weight of the human body on top of damp soil is my personal soul’s responsibility. There is no other way for me to eliminate the illusion of separation between us or make sense of the circumstances in my life.

A colony of black specks marches along toward the wooden stump on my right-hand side, in a line, while I wonder how many I’ve stepped on getting to where I am now.

What is there that hasn’t been named yet?

I still have my pen in between my pointer finger and thumb, twitching. The lines in my journal, still empty.

Billowing cotton-candy clouds remain from the sunset, pummeling the sky matching my chest with an odd curvature in my heart—bottomless gratitude for a grand experience of the sky’s last dance before darkness.

I walk back down the mountain.

There’s something new nodding its head and healed within myself.

I look back up to the landscape and wonder—what is the reason for the mountain range and clouds coming together as one moving thing that contracts and expands in time with my breath? Whose heartbeat am I hearing? △

Your Highness: Chalet Zermatt Peak

Celebrities and royalty stay at this über luxurious chalet with majestic Matterhorn views

Zermatt / Canton of Valais / Switzerland A stay at Chalet Zermatt Peak with views of the majestic Matterhorn is pure indulgence, and that begins with the location: Zermatt is one of the most beautiful mountain resorts in Europe.

“Chalet Zermatt Peak was designed to make the most of its stunning surroundings,” says Sarah Hixon- Broad, head of sales and operations at Chalet Zermatt Peak. “Floor-to-ceiling windows offer guests unrivaled views, and the interior had no expense spared to make it the most luxurious chalet in the village.” Rated “five star plus,” the five-bedroom chalet comes with a personal chef, concierge, serving staff, housekeeping, and masseuse. Though Hixon-Broad won’t drop names, she says, “We have had members of several European royal families, celebrities, and sports personalities.”

Stable in the Landscape

An award-winning Austrian architect ennobles vernacular alpine building tradition to sophisticated minimalism

Austrian architect Thomas Lechner reduces the idea of vernacular alpine architecture to a design so consequentially essential in what is left that his minimalist structures become sophisticated and sexy.

The Hochleitner house in Embach is no exception. The project’s objective was notably elemental: The client wanted a house for himself and his books; a building void of any status. “To realize this vision, we referenced the surrounding area’s simple Heustadln (hay barns) and conceived an honest wooden structure,” says Lechner, co-founder and principal at LP Architektur.

A modern mountain man of tradition

“The mountains mean a tremendous deal to me because they astonish me time and again, demand my respect, and give me a lot of energy.”

Lechner was Born in Altenmarkt in Austria’s Pongau region in 1970. After earning his architecture degree from the Technical University Graz and practicing at several firms in Salzburg and Berlin, he returned to his native alpine town to open his own atelier.

When I ask who is his idol in the architecture and design world, Lechner, whose firm is nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award 2017, replies there is no reason to apotheosize anyone or anything—“But you can regard fellows in your field and their accomplishments with respect and joy.”

The architect is happiest when he is able to be self-aware and live in the present moment. “That’s the honest life—it feels good,” he says.

The surrounding peaks profoundly inspire Lechner as a man and architect: “The mountains mean a tremendous deal to me because they astonish me time and again, demand my respect, and give me a lot of energy,” he says. “They relativize much of everyday life to what is essential.”

The Hochleitner house

Extracting what is essential also drove his design of the Hochleitner house. Completed in 2016, the 105-square-meter (1130-sqare-foot) primary residence is set in a meadow that borders a neighborhood to the north but is largely undeveloped to the south.

“The site is somewhat exposed in the landscape and requires sensibility,” Lechner says. “The architecture refers to the surrounding landscape by referencing local vernacular building tradition—a wood construction with a weathered facade, pitched roof, etc.”

Looking back at the project, the architect is proud of how the house innately adapts to its bucolic setting, and that no secondary structures, such as a carport, obscure the architecture or unnecessarily bring the form into question.

House tour

The primary building material is wood, which was used in the construction and for all surfaces on the inside. “A central stairway and varying floor levels divide a sequences of spaces—rooms that flow into one another,” Lechner describes. “This creates living zones of different qualities and internal and external contexts reduced to the essential in their formulation. All furniture and storage areas are wall elements, and the central focus is reserved for the book collection.”

The project’s biggest challenge, reveals the architect, was “the proverbial tightrope walk between reduction and banality—to continually look at the challenges of construction and functionality in reference to the targeted solution, which was to model the functional architecture of the regions farmsteads.”

"[A] proverbial tightrope walk between reduction and banality."

Lechner mastered the balancing act. The house won him the Best Architects Award 2017.

“Perhaps there is such as thing as an ‘energy’ that brings together certain people for certain tasks,” the architect notes about the design process and close collaboration with the client. “This project represents an approach where architecture is not defined through a creative will but instead through a relevant response to the place and the purpose—a simple wooden house, no more yet no less.” △

“This project represents an approach where architecture is not defined through a creative will but instead through a relevant response to the place and the purpose—a simple wooden house, no more yet no less.”

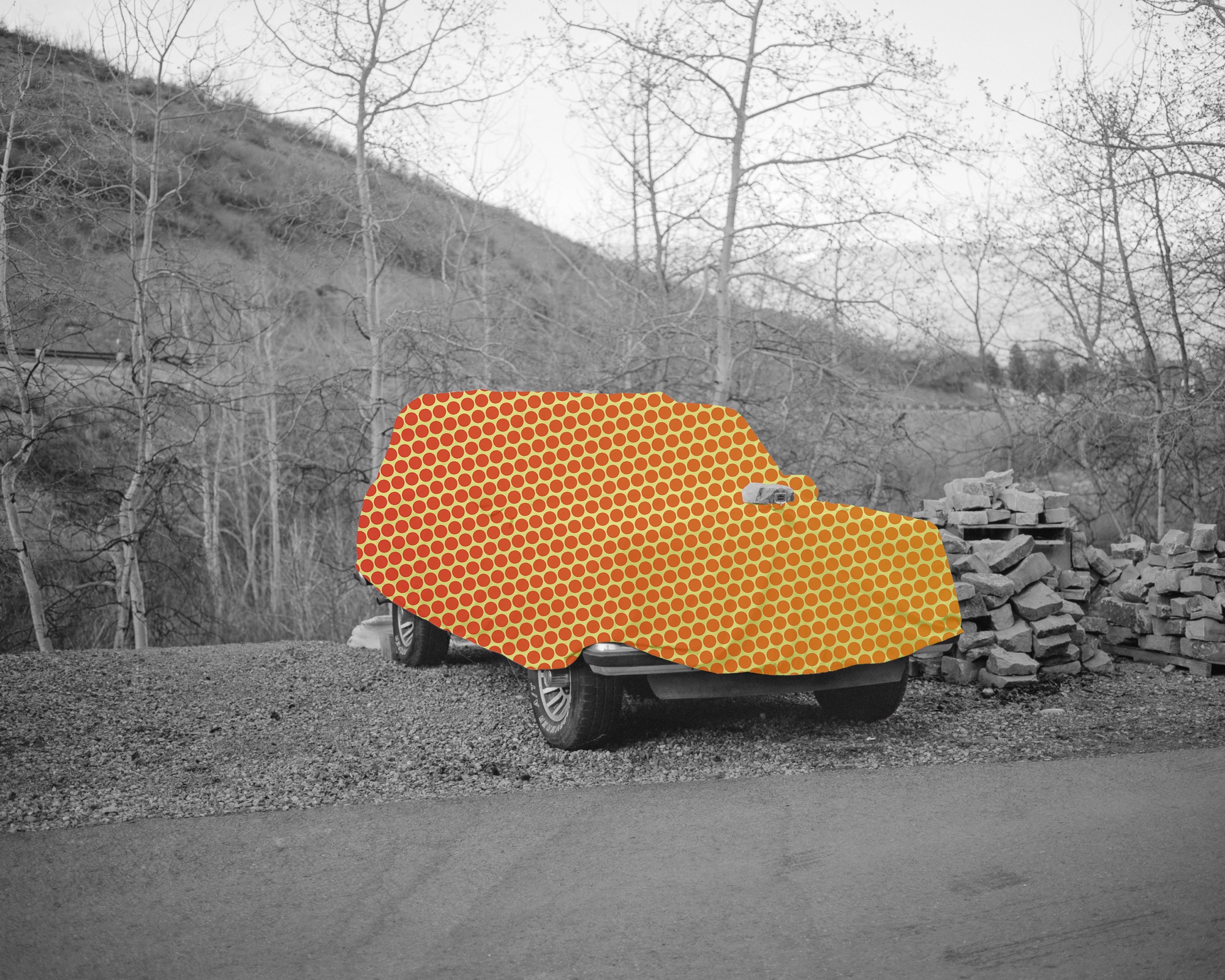

Alpine Modern + JK Editions: Fall

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints by Boulder photographer Jamie Kripke exclusive for Alpine Modern

Art Photography by Jamie Kripke A portfolio of images by Boulder, Colorado-based photographer Jamie Kripke, created exclusively for Alpine Modern. An ongoing project that studies our connection to the alpine landscape.

Limited edition, museum-quality fine art prints of these images are available to purchase through Alpine Modern.

An Aspen House Lives Up to LEED

Smart technology helps a house in Aspen, Colorado, stay on its sustainable course

The Aspen residence of architects Sarah Broughton and John Rowland aims to leave the pristine local landscape intact.

The Aspen residence of architects Sarah Broughton and John Rowland aims to leave the pristine local landscape intact.

“Every drop of water that lands on the property finds its way to the bocce ball court, which is our storm-water filtration system,” Rowland says. “By the time it leaves, and heads to the aquifer, it’s as pure as it can get.”

The couple’s house is LEED Gold certified, a rating they achieved by taking into account a number of considerations: They designed the structure so that a large tree in the front yard could be retained; construction was executed to minimize erosion and site impact; and the house itself has high-efficiency plumbing fixtures, among other features. Photovoltaic panels provide about 60 percent of the abode’s energy.

Outdoor entertaining is made possible by a wall of pocket doors from Weiland. “It really expanded the living room, because the doors just go away,” Broughton says. The couple use the Savant system to play music—two speakers are installed in the ceiling of the covered porch, and there are more in the garden. “The outdoor area rocks, literally,” Rowland says.

The residents have wired their mechanical room and solar technology to a Savant home automation system, which they use to keep an eye on the home’s performance. They’ve configured the system’s app to deliver a breakdown of the dwelling’s energy usage in a pie chart. “Last spring, when we were starting to open the windows, I looked at it and said, ‘Oh my gosh, the humidifier is running full-time, and it’s the largest energy hog right now,’ ” Rowland says. “It was time to turn it off.” He notes that they also closely monitor another culprit so it doesn’t run unnecessarily: The heat tape used in the gutters to prevent snow buildup is a big draw.

“The outdoor area rocks, literally.”

The house is optimized for gatherings. A guest apartment equipped with bunk beds sits under the garage, and a wall of sliding doors from Weiland enables indoor/outdoor functions—Broughton and Rowland once hosted a 25-person dinner party that seamlessly stretched from the dining room to the patio, thanks to tables set up in both places. Technology aids in the couple’s entertaining: Big music fans, they use the Savant system to stream audio across the property. Keyless door locks from Schlage hook up to the Savant setup, and the duo can assign visitors guest codes that will expire after they leave. But the couple purposely steered away from additional automation features—such as connected thermostats—to avoid confusing guests who aren’t familiar with the systems.

For themselves, though, Broughton and Rowland value the ability to ensure that their house is living up to its green rating. “I wish more of our clients would use tech to understand their consumption,” Rowland says. “A lot of people don’t even pay attention, and things are just running. As architects, we need to be in tune with that.”

The materials are limited to white millwork and white oak. “When we come home, we want something serene,” Broughton says. △

“I wish more of our clients would use tech to understand their consumption. A lot of people don’t even pay attention, and things are just running. As architects, we need to be in tune with that.”

Solid Form

Shaping a clump of thought: A visual portrait of ceramicist Kelli Cain

We fell in love with Kelli Cain's pure and honest ceramics at first sight when writer Winifred Bird and photographer Torkil Stavdal visited the artist for us at her studio in the Catskill mountains. Revisit her through an artful video...

earth - air + water + force / rotation x fire = solid form

This is the formula of ceramics artist Kelli Cain's creative work. In "Breakable Minimalism," Alpine Modern discovered the many-talented maker and her earthy, minimalist tableware.

Now, filmmaker James Jenkins has created a visual portrait to showcase Kelli Cain's process through a meditative stream of consciousness. The process of thinking is taking a malleable substance—a clump of thought—and shaping it. It solidifies mid-process into a shape, perfect and imperfect, unique and personal. Cain's style is simple, beautiful, and speaks for itself.

(In)complete thoughts in response...

Solid Form - Kelli Cain from James Jenkins on Vimeo.

"The process of thinking is taking a malleable substance—a clump of thought—and shaping it."

She Felt Beautiful

Swedish designer Pia Wallén talks about her iconic Crux Blanket and the bold creations she makes from wool felt

Pia Wallén, who was born in Umeå, Sweden, and now lives and works in Stockholm, creates bold, minimalist objects from her signature wool-felted materials.