Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

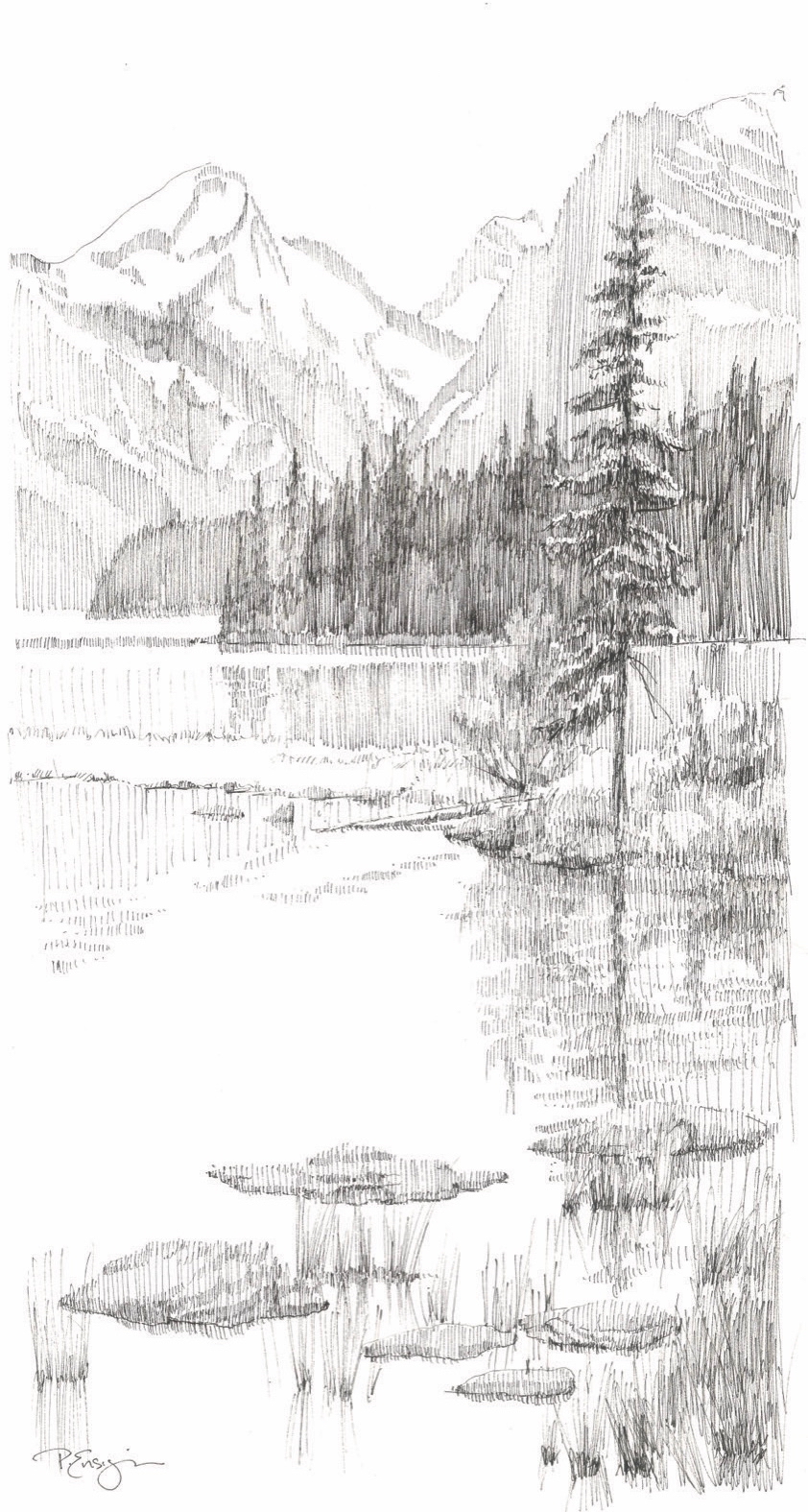

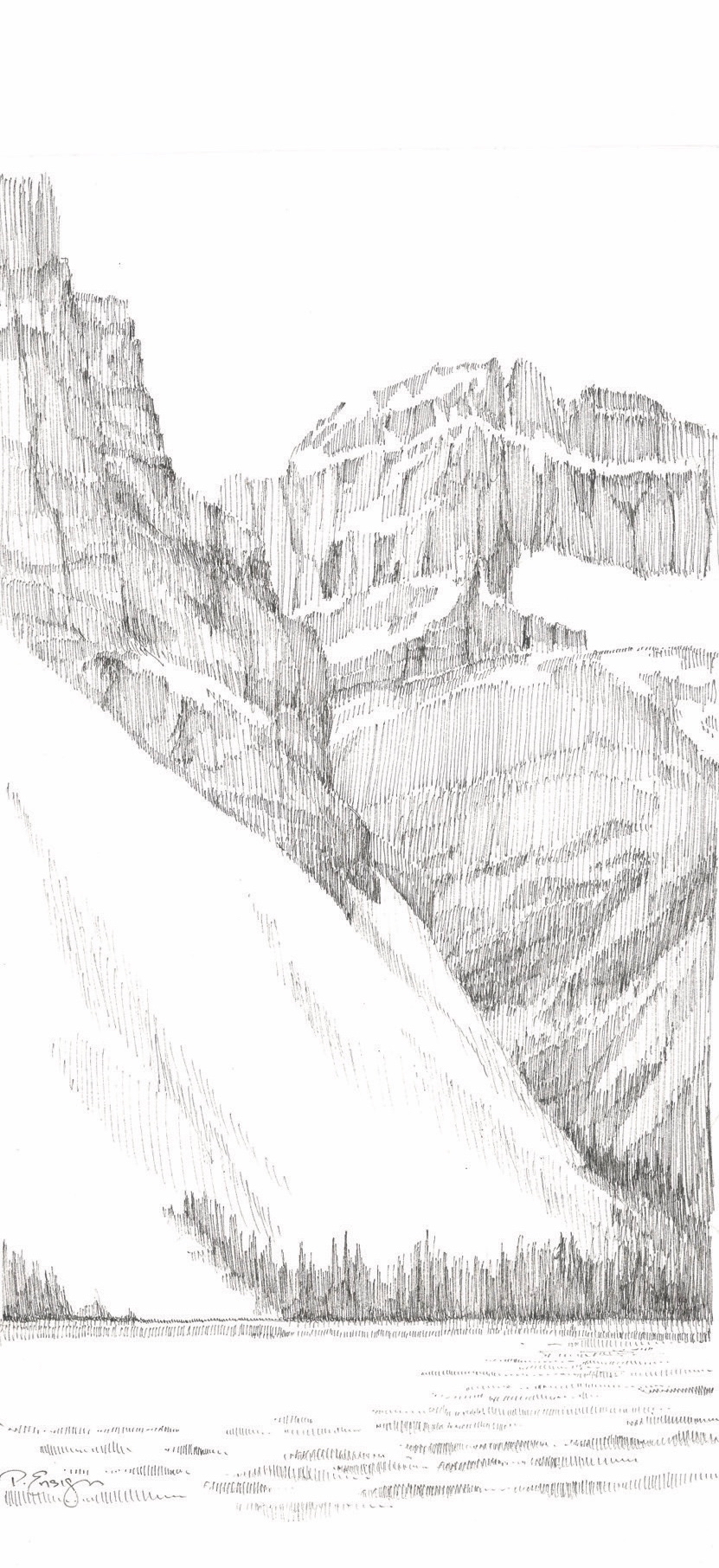

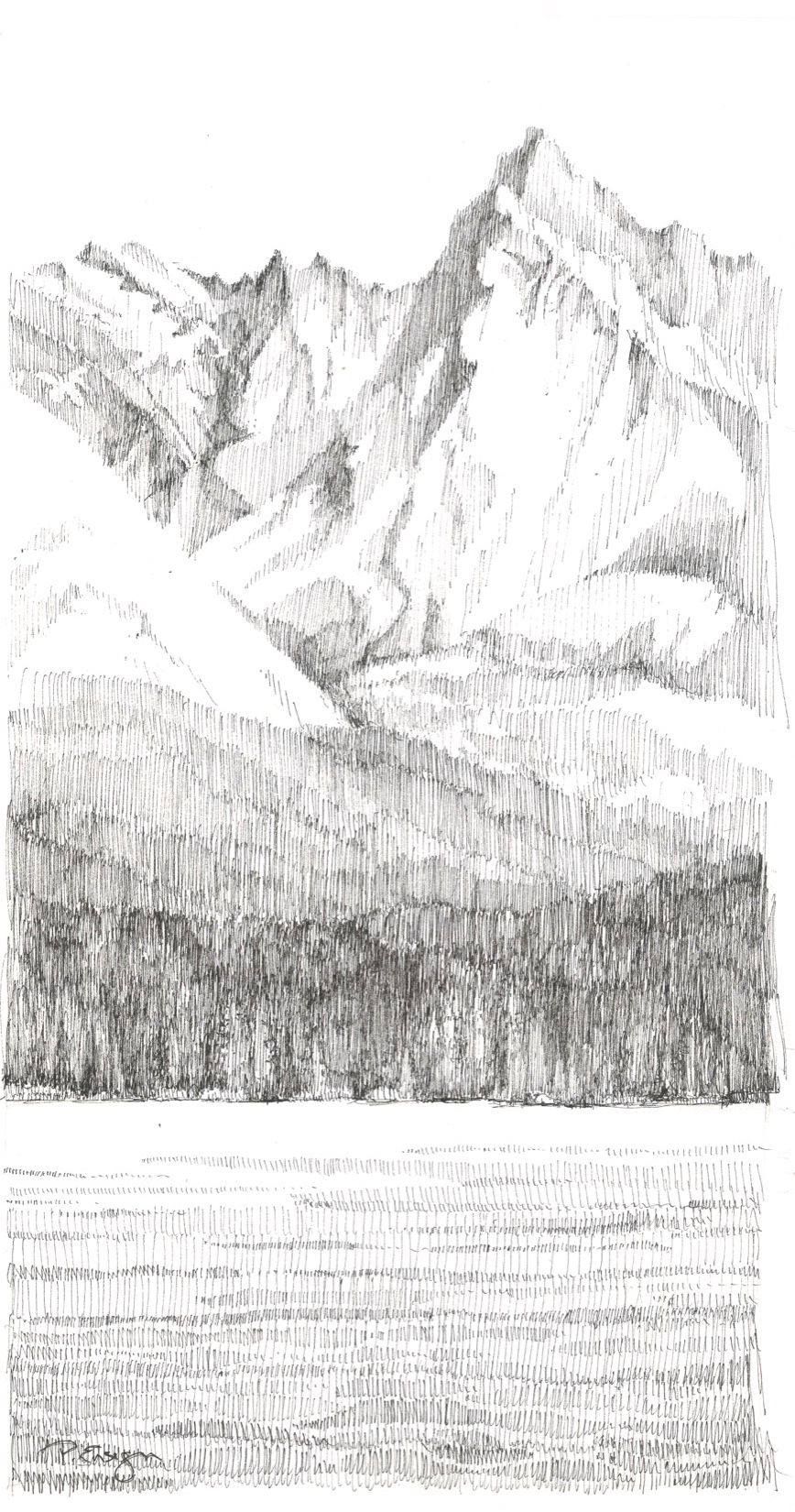

A Drawn-Out Hike

Seemingly so cumbersome compared with instagramming your every adventure, contemplative sketching in nature slows you down enough to see all the details.

In times of Instagramming every outdoor adventure in, well, an instant, slowing down to sketch a nature scene, seemingly so cumbersome by comparison, becomes a contemplative process, the details more significant for the effort.

Down a short path to the water’s edge, I find a spot beneath a lodgepole pine. I sit down on my folding stool and take in the scene before me, rugged mountain peaks descending steeply, rimming Bow Lake in the Canadian Rockies. For a few moments, I simply look. It’s a powerful and grand view. While most people might take a series of photos to document the beauty of this vista, I prefer to draw.

Drawing is quiet work. It’s my favorite way to connect with the mountains. First, I study my subject carefully. I examine each ridge and crag. I study layers of rock and sand, discover the nooks and crannies and the remnants of snow. Looking intently, I seek out proportions and relationships, consider the depths and heights, and pay close attention to the movement of light and shadow. To draw effectively is to see, really see, what’s in view. But even more than seeing, drawing on location is a total experience. Sitting on this quiet bank, away from picnickers and tourists, I hear the gentle lap of water against the shore and the birds in nearby branches. I feel the soft breeze against my face and smell the damp ground at the water’s edge along with the sweet scent of pine needles. Immersing myself in my surroundings, as I begin to draw, I let my hand and my thoughts reflect the grace of the moment.

Splendor, line by line

No special talent is needed for this task. Drawing is simply putting marks on a surface to illustrate where one’s eye goes. Anyone can experience the joy of drawing a scene before them. All that’s needed is a paper, a pencil, and a little time. Today, I start with a line drawing that identifies the big shapes, the overlap of one ridge against another. Next, I look for dark and light areas—known as values. As my drawing develops, I stay focused on my subject, constantly verifying angles and details. Lastly, I take care not to overdo the minutiae and make a point to stop before too many lines spoil the intention.

Glacier-hopping

Earlier in the day, I stopped at a pullout on the Icefields Parkway with a fabulous view of Crowfoot Glacier. The parking lot was filled with cars, campers, and buses. Tourists hopped out of their vehicles, snapped a few pictures, then jumped back into their cars to speed down the road to the next viewpoint. How will they know one glacier from the next? What memories will linger long after they have left this grand landscape?

Yes, the quiet deliberation of drawing is slow and methodical. It takes time. What could be more valuable in our hurry-up world of instant everything than to open the senses and make a lasting imprint on the soul? Take just one hour to study, absorb, and look carefully at a scene, and you will never forget it. A relationship will form, a lasting memory will be etched in consciousness. I never forget a location where I have spent time sketching.

“What could be more valuable in our hurry-up world of instant everything than to open the senses and make a lasting imprint on the soul?”

Drawing is a wonderful way to hold on to our travels and experiences. It’s never about the success or failure of the end result. It’s not about technique or individual style. It’s about the process. It’s about the time, the connection, and the quiet communion between artist and subject. △

“Drawing is a wonderful way to hold on to our travels and experiences.”

Northern Lights Optic × Alex Strohl

Canadian Northern Lights Optic collaborates with French photographer Alex Strohl

Northern Lights Optic collaborates with Madrid-born, French photographer Alex Strohl.

Orion Anthony didn’t just create a product when he launched Northern Lights Optic in 2015. He created a lifestyle.

The brand is championed by its NL-6 and acetate NL-7 glacier glasses—which were inspired by Anthony’s own exploration of British Columbia’s rugged Coast Mountains.

With their lightweight frames, classic circular lenses, and removable leather side shields—the optics pay tribute to the golden age of mountaineering; albeit with a modern twist. These signature models set the tone for the brand.

As an ode to the alpine ways of old, Anthony operates a vintage 1974 Spryte snowcat—a charismatic and unstoppable behemoth, which can often be found parked in the same mountains where the brand was conceived. Anthony works out of those confines (a space that expands into a classic canvas outfitter tent, complete with a wood-burning stove) during the winter—pulling inspiration directly from the elements for which Northern Lights Optic was developed.

It was there at NLO Basecamp where a new vision was born—one that would combine the talents and vision of French photographer Alex Strohl with the alpine heritage lifestyle created by Anthony through Northern Lights Optic. △

The Grasshopper and the Ant

Winter is coming. A classic poem about preparedness, enjoying life, and friendship.

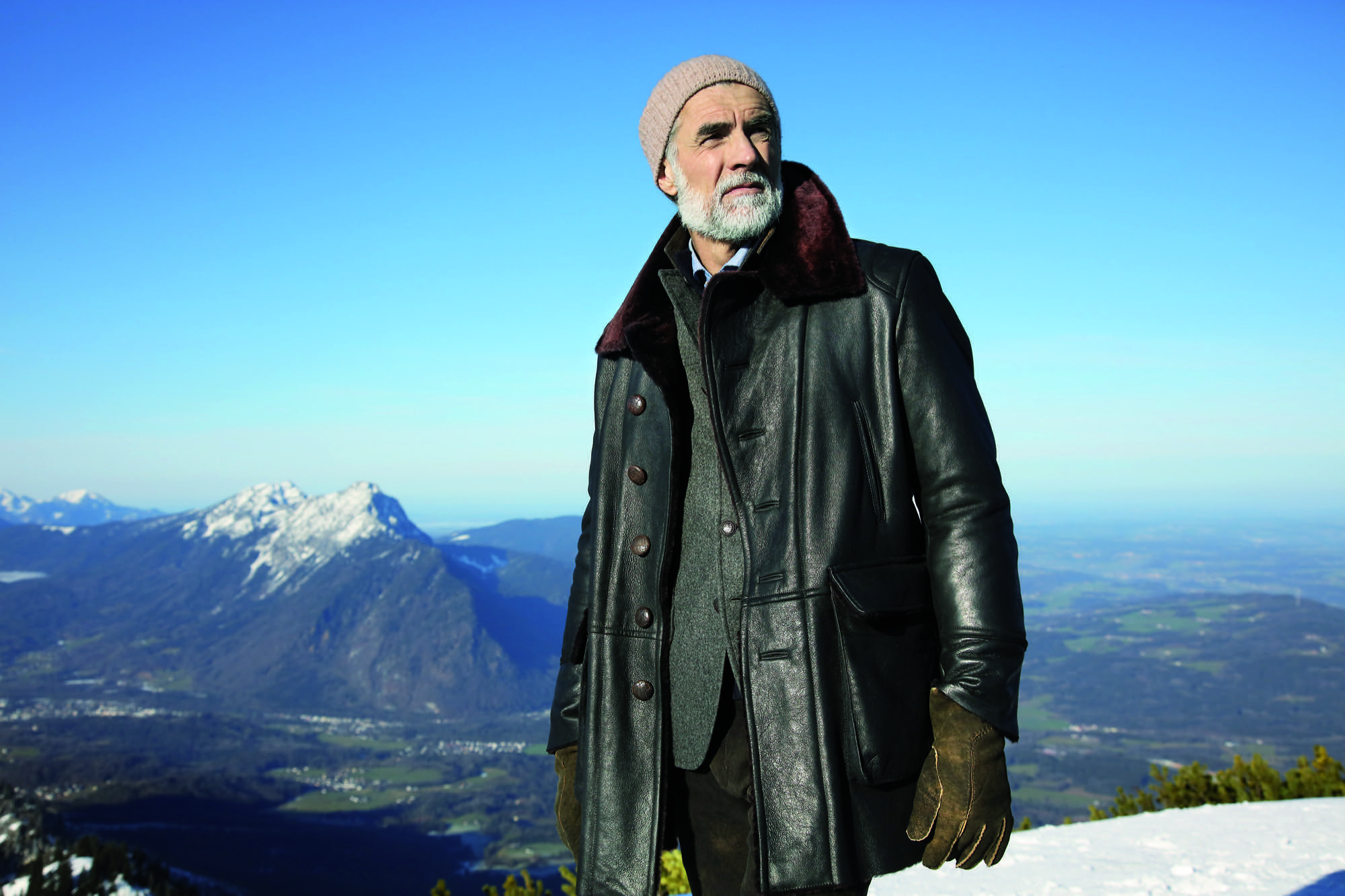

Louis Joseph on Alpine Authenticity and an Old Sweater

An uplifting conversation with the founder of the Boston-based outdoor garment label Alps & Meters

Nostalgic and progressively technical at once, the rare outerwear garments of Boston-based Alps & Meters reflect an appreciation for the authentic alpine adventures founder Louis Joseph has experienced in mountain villages around the world.

AM Your idea to start a performance outerwear brand was inspired by a trip to Sweden and a vintage ski sweater. What’s the birth story of Alps & Meters?

LJ I’ve always been an alpine sports enthusiast, primarily skiing, and I’ve traveled the world to places near and far for it. I was on a trip to Sweden—could be as many as fifteen years ago now—and I bought a vintage knit ski sweater with very interesting technical attributes. Ever since that time, the garment traveled with me wherever I went. It became a significant conversation starter in places like New Zealand, the Rocky Mountains, Europe. I let a lot of these conversations wash over me and started to think more deeply about what was so interesting and appealing about that particular piece. That was probably the springboard for Alps & Meters, trying to understand what people responded to, from the romantic nature of that piece to its technical attributes, these beautiful, rich knitted fibers, which is a bit of an art now that is lost and forgotten. That sweater transports you to a different time and place, perhaps a little simpler. There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand.

"There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand."

AM Years of research and travel went into your product creation, until you finally found the right materials and manufacturers...

LJ Yes, I am probably five years into Alps & Meters now, since it was a spark of an idea in my mind. I took many trips to a lot of different destinations, here in the United States and in Asia, to find a factory that would work with a new brand, not only a small brand, but also try to innovate and create a different expression of performance outerwear. We came up with a product-creation philosophy that we call “forged performance.” It’s a marriage of classic garment construction techniques with natural materials, like whole-grain, water-repellent leathers and nano-coated yarns, and bundling that together with contemporary technology. Many factories found the complexity too difficult to digest. I ultimately found a family-owned company in Taiwan that has been knitting garments in a very sophisticated way for decades.

I was global director of strategy and innovation at Puma and actually moved to its headquarters in Germany. I left that job a couple of years ago, turned our website on to gauge a demand for the concept, and here we are.

AM What does your brand name—Alps & Meters—represent?

LJ We wanted to convey a sense of tradition and a classic appreciation for authentic alpine sports. Obviously, the Alps came to mind in terms of all their transportational values, and this very traditional, true atmosphere. The word meters has a double meaning within the context of our brand: meters not only in terms of height and the expansiveness of mountains and ranges, but meters is also the unit of measurement for tailors. We wanted to have that underlying meaning closely connected to the brand, because we are really trying to refine our garments and express a form of outerwear that’s very meticulous in terms of attention to detail and the materials we are using. This unit of measure helps us to think very creatively of tailoring the pieces in a manner that is not only differentiated but still provides first-class, on-mountain fit and protection. I always think of the old tailors’ measuring tape, that really rich, yellowed meter tape. And we love the ampersand in the brand name. “Alps & Meters” has a bit of an old-world family feeling to it that I think is nice and sturdy.

AM What makes you a mountain man at heart?

LJ I grew up skiing, primarily in the United States, and I fell in love with the sport— not only the sport’s individual aspect of being on your own in the mountains and having that quiet and connection to nature, but there was always a camaraderie and a friendliness about the places that I traveled to, where people can affiliate and relate, whether they are in Japan, Europe, South America. It always struck me that that same sensibility was shared and crossed generations. Before I got married, I spent a lot of my money on a couple of interesting ski adventures. I’ve skied in the summer, too. I’ve been to Argentina, and I’ve made my way to Chile. I always appreciated connecting with new cultures, primarily in mountain settings, and those simple double-chairlift rides, meeting somebody new, from a different background, a different place, speaking a different language.

It actually has always been a rite of passage and a tradition for the Alps & Meters team to ski a glacier at the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range. It’s about a four-hour hike with full pack, boots, skis. You start below the tree line, and all of a sudden you are in a snowy environment.

AM You have a deep connection to Vermont. Why did you open your office in Boston?

LJ My wife and I got married two years ago at a beautiful inn in Vermont. Much of the concept for Alps & Meters was born from ski trips to Vermont, sitting outside around a fire, snow falling, talking with staff who are avid skiers and alpine enthusiasts. We’ve tried a virtual headquarters in Vermont for some time, but the logistics were really challenging. Alps & Meters has deep roots here, but our team is now settling down in Boston, which is wonderful for logistical purposes, travel to Europe, shipping is very easy.

AM You strive for authenticity. How does this intent translate into your brand?

LJ There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else. That is something I love about European skiing, a timelessness and authenticity that crosses generations. It’s wonderful to hike the same trail, ski the same routes, or ride the same lift somebody had done fifty years ago.

At Alps & Meters, we are trying to express a very deep appreciation for classic alpine tradition, and that expression is obviously manifested in the products we are creating. The materials we are exploring are authentic. They are tried and true.

They have always stood the test of time. There are performance characteristics, but their aesthetic is very authentic, and they are a recall to that authentic experience. There is a great confidence in entities that are authentic, and they have a real gravity that can be felt. I’ve been to Chamonix, for example, and it just resonates with authenticity—the people, their respect for the mountains, how they treat one another. It’s one of those very difficult feelings to describe, but you know it when you see it.

“There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else.”

AM You launched Alps & Meters with a small collection of three pieces. Talk about your flagship product, the men’s shawl-collar jacket.

LJ We are really trying to make a statement with this shawl-collar jacket and keep our exposure low in terms of the breadth of the product collection. The shawl-collar jacket is a very nostalgic piece from the perspective that it is actually a properly knitted garment. In today’s menswear world, there aren’t many factories or brands that are actually knitting goods. We wanted to revisit proper knitwear that’s protective, warm, has great range of motion and ergonomics, and apply that to an outerwear garment that has a contemporary stance. That type of classic garment construction technique was actually the first wind stopper. You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today. Leather is another material we feel has a very timeless nature. What’s special about that versus synthetics is that leather has always been used for maximum durability. It’s still probably one of the most durable materials you can find and apply if you are looking for garment reinforcement and protection. But what we find really intriguing is leather will wear in; it will take on patina in color, and nicks and scratches will become a memory keeper. You remember when the garment was marked a certain way, on a certain adventure.

“You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today.”

We have since evolved, and we have six or seven pieces, including a beautiful alpine winter trouser this coming winter. In our next collection, we are also modeling an alpine anorak, a pullover, on a piece that was used by the 10th Mountain Division as a protective snow garment. We are making that from a British-milled impregnated, waxed cotton. It’s windproof, it’s water repellent, and it intrigued us from a performance point of view. Again, I’m surprised that such a highly durable, tactile, beautiful material that will also have interesting wear characteristics wasn’t being used in performance outerwear.

AM Your outerwear may evoke nostalgia in the older generation while appealing to younger winter sport enthusiasts for its performance aspects. Who is your target audience?

LJ When I was traveling in my old Swedish knitwear piece, the age range of individuals who felt my sleeve in the lift line or asked me about that piece was very diverse. We are still trying to learn where the intersection is of our forged-performance differentiation and the interest level, whether it is rational or emotional or a combination therein. We are feeling our way through the dark but are really trying to stay true to what we believe, which is a respect and appreciation for simple, timeless alpine tradition.

Personal Brief: Louis Joseph

Born

1973 in Santa Monica, California

Then What?

After a stint in California, my family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, then settled in Boston, Massachusetts— fittingly, during the Blizzard of 1978. I began skiing in the mountains of New England from a very young age. My earliest years on the slopes were spent in North Conway, New Hampshire, at mountains such as Cannon, Attitash, Cranmore, and Wildcat.

In my post-university years, I gravitated toward telemark skiing after having been intimately introduced to the tradition by a close Italian friend from the Dolomites of Italy.

Now Lives

Boston, Massachusetts, in a quaint area called the South End, a walkable, friendly neighborhood of side- walk restaurants, pubs, and coffee shops.

Lives With

I live with my wife, Vinita. She is my best friend and an adventurous spirit who shares my passion for the mountains and any sort of outdoor recreation.

Favorite Place in the World

My favorite place is to be fireside in an après-ski setting. I find no greater joy than exhausting myself skiing with friends and family and then reliving that shared experience through storytelling, a crackling fire, and the satisfaction that comes with a day well spent on the mountain.

Next Big Journey

My wife is Indian, and we hope to visit India together sometime over the course of the next eighteen months. One of our dreams for this trip is to extend the adventure to Nepal and visit the base camp of Mount Everest.

Life Philosophy

Philosophically, I’m hopeful that I am leading a life in which I have my eyes open to new experiences, a sense of adventure, stay firmly grounded with humble perspective, and express a constant thankfulness for the opportunities afforded me while being kind, considerate, and helpful to those less fortunate.

Favorite Piece of Clothing

I appreciate clothes and equipment that are timeless in their utility and presentation. Therefore, my favorite piece of clothing is my father’s official U.S.-issued peacoat, which he wore while serving in the Coast Guard in the 1950s. Made from heavy boiled wool with a uniquely high collar, this jacket’s cut and sewn simplicity belies a warmth, durability, and protective nature that rivals contemporary outerwear of today. It’s also a powerful memory keeper as my father’s name, military company, initials, and year of issue are scratched on the interior in indelible chalk. When I’m not wearing my Alps & Meters shawl collar jacket, my father’s peacoat keeps me timelessly stylish and warm because of its deep family connection.

Inspired By

My mother and father have been my greatest influence and have been a well of inspiration to me throughout my life. My father is a first-generation American who instilled in me a strong work ethic and a “can-do” mentality. My mother is full of humor, mischief, and adventure, and I thank her every day for teaching me to ski. Their combination of values, imagination, and powerful encouragement have inspired me to follow my passions and, without a doubt, set me on a trajectory to explore, create, and launch Alps & Meters. △

Title photo by Torkil Stavdal

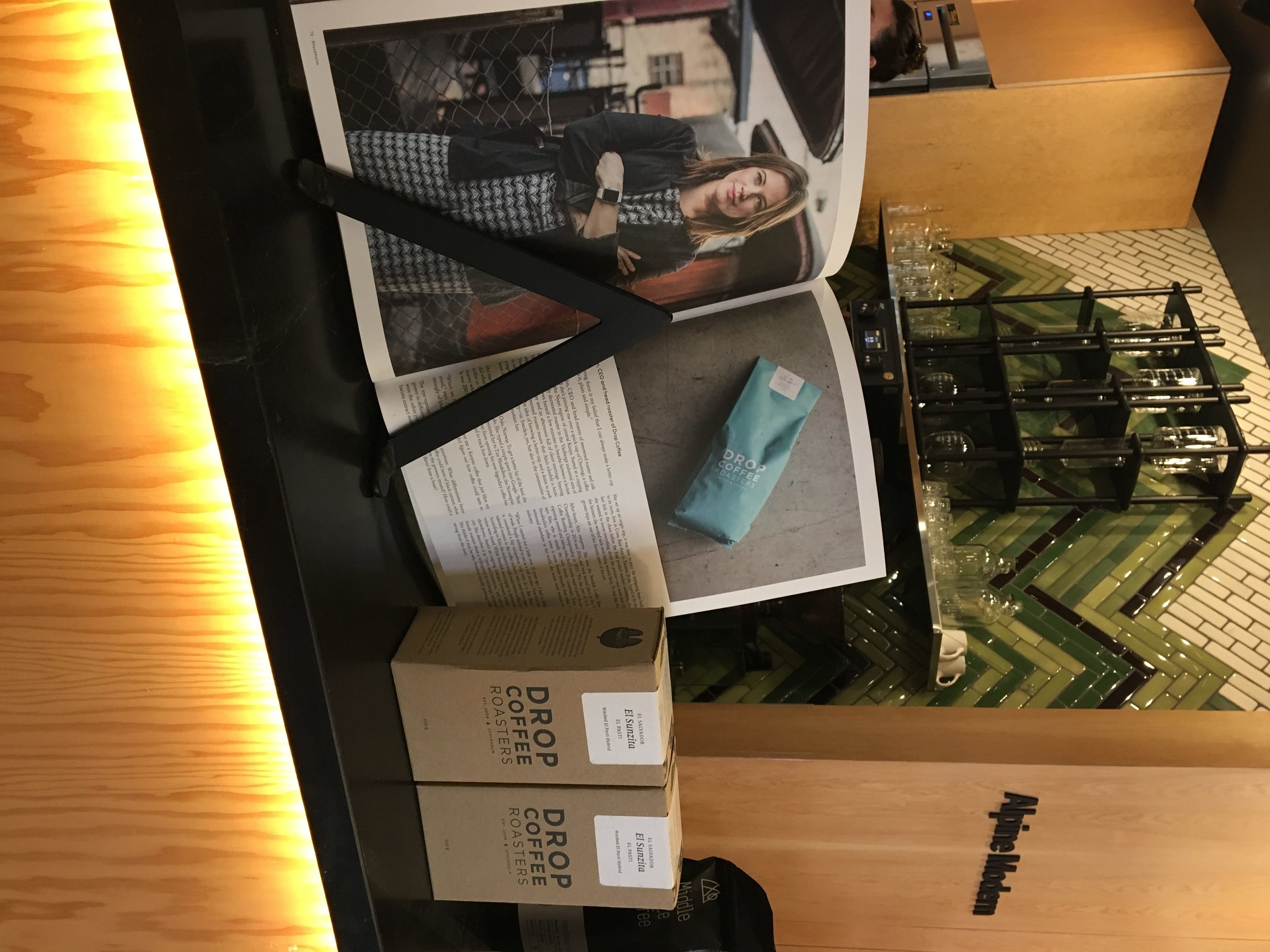

Drop Coffee at Alpine Modern

We debut our new monthly guest roasters program with a revered household name from Sweden

At Alpine Modern, in our effort to give our community access to high-quality and interesting coffees, we have begun a monthly guest roaster program. While still consistently serving single-origin and blend offerings from MiddleState Coffee on espresso and drip, we will bring in a new roaster each month to offer variety to our customers in our batch brew coffee. We will also be selling whole bean packages of the coffees.

Stockholm’s Drop Coffee

We debut with Drop Coffee as a unique opportunity to taste an extremely high-quality and long-sought-after roaster and bean.

For coffee aficionados, the Swedish roaster Drop Coffee has been a revered household name. The chance to visit the famous roaster and take classes in Stockholm is considered a sort of pilgrimage for the dedicated barista.

The company started in 2009 and quickly became a leader in the specialty coffee world. Using a direct trade model, the roaster mainly sources from Bolivia, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Ethiopia, and Kenya. For several years, Drop has won Sweden’s Roasting Championship and has placed in the top five at the World Roasting Championship since 2014. Sourcing from green-coffee importer Nordic Approach, started by the well-known Morton Wennergaard and Tim Wendelboe, Drop receives some of the highest-rated varietals currently in production.

In an interview with Kinfolk, Joanna Alm, co-owner and head roaster, outlined Drop’s coffee philosophy:

“We strive to bring out all the good natural flavors of the coffee in the roasting process without adding any roast tones. It’s crucial for us to keep all the natural flavor of the coffee throughout each step of the production chain, from the cherry to the final cup, regardless of the brew method. This is a bit controversial on the coffee market, but it’s the only way to achieve our aim to get most out of the product.”

"It’s crucial for us to keep all the natural flavor of the coffee throughout each step of the production chain, from the cherry to the final cup, regardless of the brew method."

The Coffee: El Sunset

The coffee, El Sunzita from El Salvador, is a Bourbon hybrid called “hybrid El Pasti” that comes from the farm of Mauricio and Mary Ortiz in the growing region of El Pasti.

Joanna Alm writes on the Drop Coffee website:

”El Sunzita is a great example of driven producers who are putting in the extra work to higher the quality Mauricio Ortiz and Mary Ortiz are looking at their microclimate and trying to work the most organic they can in an area suffering hard from leafrust. The location of the farm and the view is something else and one of the most beautiful farms I’ve visited.”

“Bourbon” is a coffee varietal that was brought from the Indian Ocean island of Bourbon (Reunion) in the early nineteenth century and was transplanted in Brazil, Central and South America, and Rwanda. It soon grew popular because of its ability to produce quickly and efficiently. El Salvador, in particular, is known for the varietal that offers toffee and caramelized notes. The Ortiz’s Sunzita is a special hybrid of the Bourbon varietal and makes up about 65% of the farm that sits in Santa Ana at 4,000 feet (ca. 1220 meters).

The coffee is fully washed; meaning all the pulp surrounding the bean is cleared away, leaving a clean, bright cup of coffee with very little inconsistencies. El Sunzita has a medium body with notes of raisin, chocolate, and dark cherries.

The high quality of the bean is mirrored in the sleekness of the packaging design. 250 grams are sealed in an airtight plastic re-sealable package and placed inside a small tan box that features an intricate line-work drawing of a coffee cherry and plant. Alpine Modern is selling these limited edition packages for $20 each.

For the rest of October, come by the Alpine Modern Café at 9th and College in Boulder or our new Alpine Modern Shop + Coffee Bar at Pearl West to sample El Sunzita on our Curtis batch brewers or take home a bag of this sought-after coffee. △

Earthbeats

"The mountains speak in an unlearned language that I love."

All I’ve known to cure myself is this— Blue and green hues pulse together while I’m lying lonely on top of pine needles. Rows and rows of trees with peeling, orangey skin align, and the symmetry feels safe. It’s nearly sundown, and the whirring noises are far away in the city. All I can hear is clarity and crickets.

Colorado is my home now.

The tree bark is my creative chair. My brown leather journal lies in my lap, but I don’t know where to start, or which questions to ask that I haven’t written down yet.

The wind touches my skin, and breath branches into all parts of my body in bold colors.

Most of my thoughts reflect the relationship we have to the earth. I’ve realized how feeble my body has always been at such a young age, filled with air and always wanting something looming overhead. The mountains move me further from feeling like I need answers. The mountains speak in an unlearned language that I love.

I close my eyes and slide farther down onto the ground.

Land cradles my body, comforting me like the child I crave to stay. Returning to the roots of existence and feeling the weight of the human body on top of damp soil is my personal soul’s responsibility. There is no other way for me to eliminate the illusion of separation between us or make sense of the circumstances in my life.

A colony of black specks marches along toward the wooden stump on my right-hand side, in a line, while I wonder how many I’ve stepped on getting to where I am now.

What is there that hasn’t been named yet?

I still have my pen in between my pointer finger and thumb, twitching. The lines in my journal, still empty.

Billowing cotton-candy clouds remain from the sunset, pummeling the sky matching my chest with an odd curvature in my heart—bottomless gratitude for a grand experience of the sky’s last dance before darkness.

I walk back down the mountain.

There’s something new nodding its head and healed within myself.

I look back up to the landscape and wonder—what is the reason for the mountain range and clouds coming together as one moving thing that contracts and expands in time with my breath? Whose heartbeat am I hearing? △

Zen and the Art of Knife-Making

Using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, a blacksmith in the Japan Alps makes knives so delicate and dangerous they turn chopping into an artful act of passion.

A blacksmith in the mountains of Japan uses skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword- making to forge knives from a steel that is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art.

Cutting, slicing, mincing, dicing, boning, peeling: Over time, these mundane jobs have become, for me, the most satisfying tasks in the kitchen. Now, I experience knife-work as a meditation on all that will unfold after food leaves the chopping block. With each cut, I’m trying to shape ingredients to their ideal form, whether it’s a fine mince of onion designed to melt in a pan as a base for a sauce or fifty wedges of apple that need to keep succulence while retaining their shape in an autumn pie. The key to this repetitive-motion, Zenish state is a sublime knife: balanced in the hand, dangerous, delicate, an obedient lover and assassin.

I found my sublime knife after a lot of looking. It has a blade of Aogami Super carbon steel and was hand forged in a mountain town called Niimi, 150 kilometers (93 miles) northeast of Hiroshima, at the shop of a fifty-seven-year-old blacksmith named Shosui Takeda.

My Takeda

If you lay my Takeda 180-millimeter Super Sasanoha Gyutou chef’s knife beside my shiny stainless Shuns and Globals and Henckels, it looks weathered, almost preindustrial. The thin blade has a mottled black finish called kurouchi. The blade tapers sweetly to a gunmetal gray edge whose sharpness approaches that of a razor. You can see the resin used to affix the tang as it was slid into a hole in the Indian rosewood handle during construction. The handle is octagonal, to answer the shape of enfolding fingers and palm. Near the upper rear of the blade’s spine, roughly stamped into the metal, are Japanese characters, plus a heart and the Western letters AS. The characters mean “Niimi. Shosui. Aogami Super.” The heart is something Takeda-san’s blacksmith father started to put on his blades many years ago. Takeda-san says he has never been quite sure what the heart means.

Finding the perfect blade

I have not been to Niimi. I met my Takeda—and, later, two more of them—through Google’s search power and the matchmaking tastes of an American in Tokyo named Jeremy Watson. Watson is a thirty-nine-year-old American of UK and Hong Kong ancestry who moved to Tokyo after a period teaching English in Japan (where he met his wife) and a period learning about, and selling, Japanese knives in Manhattan. In 2012, he founded Chuboknives.com, selling products he found by scouting artisan blacksmiths around Japan. Initially, he hand-wrapped each order, inserting a thank-you note into slim boxes covered in Japa- nese stamps, and sent them on their way to Australia, Europe, and the UK, where chefs and foodies were beginning to notice his trade in rare beauty. Now his business is such that he has automated the shipping. But the boxes remain lovely and intricate, befitting jewelry, and to receive a Takeda in the mail feels like a gift, even if you’ve paid for it.

“We wanted to be a small family business that was connecting small-scale artisans to chefs and home cooks,” Watson says. Big Japanese knife-makers, like Shun and Global, were taking up more and more display space in stores like Williams-Sonoma (where once German companies like Henckels had ruled), but “I realized that the smaller artisans and blacksmiths were really underrepresented. Shibata, Takeda, or Tanaka—the craftsman that we’re currently working with—weren’t really out there.”

The absence of these knives from the major retailers can be explained by the minuscule production of operations such as Takeda Hamono, as the company is called.

Takeda's workshop

“There are three blacksmiths, including me, at the shop,” says Shosui Takeda (whose answers were translated for me by Watson). “We spend eight hours a day forging, twenty-five days a month. In total, we produce 250 knives a month. If we calculate the number of hours all of us work, essentially each person is producing about three knives per day.”

The quality of a handmade knife derives from the strange mutability of steel when it’s repeatedly heated and hammered to alter its molecular structure. The blacksmith, using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, is always chasing an ideal: a blade strong yet somewhat exible, thin but not brittle, able to take an edge and hold it for a long time. A molecular map of a knife would reveal a variety of attributes across its form, determined by cycles of quenching (to harden the steel) and tempering (to selectively soften it). The spine may be softer than the edge. The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it. Takeda has been using AS for twenty-five years, after discovering it in a steel-maker’s catalogue, and after realizing that customers would pay a premium for the uncanny thinness and edge retention that AS offers. “As far as what I’ve seen,” Watson says, “I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as he does.”

“As far as what I’ve seen, I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as [Shosui Takeda] does.”

"The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it."

Watch the YouTube videos of Japanese knife-makers at work: heating steel and iron to narrow temperature tolerances in coal-fired furnaces, then beating away at the metals—using both power hammers and tools wielded by hand—until they begin to fuse and morph like slow-motion Plasticine. The shape of the knife is judged by eye—as is the temperature of the hot steel, judged by the color of its glow in the fire. Heat, hammer, cool, and repeat. Sparks fly. The blades curl out of shape, then return to form under the blacksmith’s art. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding.

"I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding."

That said, Takeda’s approach benefits from modern insights. “I’ve learned a great deal by collaborating with the steel-makers. Through trial and error and using high-resolution microscope photography to see how the steel looks after it’s forged, I’ve been able to eliminate problems with the forging processes.” He quenches his blades in successive baths of hot oil, whose temperature is closely regulated, then sharpens the edge with wheels and stones of increasingly fine grit. His wife and two daughters fix the tangs in the handles at the end, and handle other shop duties.

Dangerous business

The work looks dangerous because it is: “When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves,” Takeda says, “we get burns on our hands and arms every day. This is just part of the job and no big deal.

“What’s more serious are the repetitive strain injuries to my back, shoulder, elbow, and knees. Eight years ago, I had back surgery, and earlier this year, I had surgery on my right knee. I’m currently doing monthly injections so I can keep working. My grip strength is also significantly weaker than it used to be.

“The most serious is the hearing and vision damage. I use earplugs, but I still have hearing damage. Also, constantly looking at the coal-burning oven while forging has damaged my sight.”

"When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves, we get burns on our hands and arms everyday. This is just part of the job and no big deal."

All that pain may explain the paradox of the knife market in Japan. The rise of the global food and chef culture has created unprecedented demand for fine knives, and Watson says artisan shops have more orders than they can fill. The Internet makes new connections between cooks and artisans possible. It would seem to be a perfect time to grow a blacksmith’s business.

“The American solution to this would be to hire more people and build a larger facility,” Watson notes, “but that’s not necessarily the mentality here. A blacksmith team consists of three or four people, and it takes years to train.” Nor are young Japanese lining up for the work. This does not surprise Takeda. He did not intend to be a blacksmith himself; he helped around his father’s shop for bowling money, and didn’t take up the work properly until he was twenty-eight. Were his father not in the trade, he would never have pursued it.

Takeda describes the paradox this way: The knife business is good, the forging business is not.

“During my father’s time,” Takeda says, “there were forty-seven blacksmiths in Niimi—most making agricultural implements [as Takeda’s shop still does]. Now, there are just a handful. The small knife-forging business is literally going extinct. There are very few blacksmiths left.”

Care and maintenance

In my knife drawer are Japanese stones that I use to keep my Takeda knives sharp. The stones, soaked in water, give up a creamy slurry as the carbon steel of the knife is drawn across it. When the knives are done, I use a special little stone to smooth the water stones for the next session. Sharpening is a calming ritual that with a little practice leads to a gleaming thin line of razor sharpness along the gray edge of the blade.

When the knives are sharp, and again after every use, I carefully dry them, because Aogami Super is extremely prone to oxidation. It rusts in minutes. The rust is removed with a light scrub, should I fail to completely dry the knife; this is another little ritual that I enjoy. Takeda is now making an AS line with stainless cladding, which he calls NAS, to prevent rust, but I shall stay old school on further orders as long as he continues to produce them. And there will be further orders, even though his knives run from $120 for a beautiful little paring knife called a “petty” to $380 for an absurdly long, wondrously light Kiritsuke slicing knife that is my favorite cooking tool in the world.

Takeda’s blades have a gentle fifty-fifty bevel, meaning that each side of the blade tapers equally to the cutting edge. This is easier to sharpen for an amateur than the single-side bevels common on many Japanese knives. Beveling and blade shape, like everything else to do with Japanese knives, are complex and relate to the food to be cut: vegetables versus meat versus fish. Some blades are designed for species of fish, others according to what the fish is going to be used for. Everything is about form: of the blade, of the food.

These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief. One gets a glimpse of it at a very good sushi bar, while a multicourse kaiseki meal in Kyoto is like a doctoral dissertation.

"These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief."

Wielding my Takedas, I know that I shall never have such skills. But I do have knives that allow me to meditate on the ideal every day. △

Recipe: Muscovy Duck Breast with Chanterelles, Pickled Radish, and Foie Gras Gastrique

A fine duck dish starring mushrooms and pickled garden gems preserved from summer

INGREDIENTS muscovy duck breasts: 2 breasts salt pepper grapeseed oil chanterelles: 113 g (4 oz) shallot: 1, diced butter: 28 g (2 T) thyme: 3 sprigs

GASTRIQUE

reserved apple liquid: 236 ml (1 cup) from Whiskey Preserved Apples recipe shallot: ½, diced bay leaf black peppercorns apple cider vinegar: 118 ml ( cup) rendered foie gras fat: 30 ml (2 T)

Duck Breast

Preheat oven to 180° C (350° F). Carefully score the skin with a sharp knife. Season tempered duck breast generously with salt and pepper. On medium-high heat, heat grapeseed oil until the oil is hot. Sear, skin-side down, until skin is nicely golden brown. Place pan (with the duck in it) in the oven until the duck breast reaches 54.4° C (130° F). Remove duck from the pan, let it temper for a few minutes before slicing. Finish sliced breast with sea salt and set aside.

Chanterelles

Carefully clean the mushrooms to remove excess dirt. Once clean, heat a pan, add a small amount of grapeseed oil, and add diced shallot. Once the shallot is translucent, add the mushrooms, season with salt and pepper, and cook for 3–5 minutes. Add a knob of butter and a few sprigs of thyme. Once butter is melted and mushrooms are coated, remove from pan and set aside.

Gastrique

Remove half of the liquid from the cooked apples (see recipe). Place in a saute pan with diced shallot, bay leaf, and black peppercorns. Reduce liquid by half, add apple cider vinegar. Reduce the liquid another quarter (total time 8‒10 minutes). Strain and return to cleaned sauté pan. Add a tablespoon of rendered foie gras fat for flavor. Season with salt and pepper. Stir and set aside.

Pickled Radish

See recipe for Red Wine Pickling Liquid. Set aside 3‒5 wedges.

To serve

Place the sliced duck, chanterelles, and pickled vegetables on a plate and pour the gastrique on top. Serves two.

Other garnishes include

Pickled gooseberry, green strawberries, pickled cherries. It’s easy to substitute any of these as need be. △

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Recipe: The Alpinist's Larder

A preserved whiskey drink spiked with the taste of the summer passed

INGREDIENTS

pickled cherries: 3 pieces preserved whiskey: 60 ml (2 oz) leopold bros. three pins herbal liquor: 20 ml (0.7 oz) lemon juice: 20 ml (0.7 oz) honey syrup: 20 ml (0.7 oz)

DIRECTIONS

1 Combine all ingredients into a shaker 2 Gently muddle the cherries 3 Shake with ice 4 Double strain over ice 5 Garnish with cherries, mint, and lemon peel.

Recipe: Alpine Hot Toddy

Enjoy a warming drink in memory of the summer harvest

INGREDIENTS herb bundle: Thyme, marjoram, sage, lemon peel, mint, sorrel whiskey preserved apples: 30 g (1 oz), diced violet flowers preserved whiskey: 60 ml (2 oz) leopold bros. three pins herbal liquor: 20 ml (0.7 oz) lemon juice: 20 ml (0.7 oz) hot water: 1 pitcher

DIRECTIONS

1 Place all ingredients into a heat-resistant pitcher 2 Add hot water to steep (1‒2 minutes) 3 Strain into a heated mug or glass 4 Garnish with apples and lemon peel.

Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Boulder bartender Jon Watsky making the Alpine Hot Toddy / Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

Boulder bartender Jon Watsky making the Alpine Hot Toddy / Photo by Ashton Ray Hansen

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Recipe: Whiskey Preserved Apples

Bag summer for a little while longer. Winter is coming.

INGREDIENTS Honeycrisp or Gala Apples: 2 peeled, quartered, and cored Rye or Bourbon whiskey: 300 ml (10 oz) Honey syrup: 60 ml (2 oz)—1:1 ratio honey:water Thyme: 1 sprig Sage: 1 sprig Lemon Peel: 2 peels Orange Peel: 2 peels Fennel Seed: 3 g (⅔ tsp, 0.1 oz) Clove: 3 g (⅔ tsp, 0.1 oz) Cinnamon Stick: 1 small

DIRECTIONS

1 Blanch (for 2–3 minutes) and shock the apple quarters. 2 Place all contents into a cryovac bag and seal. 3 Using an immersion circulator, poach the contents for 3 hours at 48° C (118° F). 4 Save liquid for the Alpine Hot Toddy recipe.

This recipe accompanies "Preserving Traditions."

Preserving Traditions

Savor harvest flavors well into winter by preserving the simple traditions and the sweetest fruits of alpine summer.

Preserving fresh foods so they will provide lasting sustenance through the cold season has been the stuff of daily life since the beginnings of human civilization—nowhere more so than in the mountains and other places where winter lingers.

Cured, dried, smoked, and salted meats and fish. Buttermilk, kefir, and cheese from fresh milk. Wine, spirits, beer, and cider. Pickles, krauts, jams. Tea, coffee, and kombucha. Many of our favorite foods and drinks are created through preservation and fermentation.

Cultured heritage

Passed down through generations, these basic methods served as important tools for surviving lean times. They also served, and can still serve, as familiar rituals that weave and strengthen family and community ties—and enliven our palates, hearths, and communal tables.

Your grandmother may have canned, but with the industrialization of food in the past half-century, many of us have lost touch with this inherited knowledge. Today, people around the world are paying more attention to what they eat and where it came from, tuning in to seasonal foods grown where they live, and reclaiming the simple labors and rewards of growing, preparing, and preserving some of their own food.

Sour beers, probiotic-rich fermented foods, and artisan pickles and preserves are now mainstays at craft breweries, farm-to-table eateries, even grocery stores. In many ways, it’s the rebirth of a more handcrafted, gastronomically rich world, one you can share with your family and generations to come.

"In many ways, it’s the rebirth of a more handcrafted, gastronomically rich world, one you can share with your family and generations to come."

Craft, quality, and connection

Everyone is evidently busier than ever these days. So why this nostalgic look backward at earlier ways of life and at “slow-food” traditions? Amidst the rush, we intuit the importance of slowing down every once in a while to can, pickle, or bake a pie... or to savor a nice bottle of wine or a great cup of coffee. It’s the only way we actually live in the moment. Instant gratification is rarely authentic and ultimately without value.

Preserving basic foods is often done when there’s a surplus of a food: peak season or a bumper harvest. Gathering in a kitchen with a group of people committed to one project, like jarring ramps or canning tomatoes, is a good source of inspiration. Making your own food and creating foods you can’t easily find elsewhere creates a potent connection. People will always gravitate toward craft and quality.

"Making your own food and creating foods you can’t easily find elsewhere creates a potent connection."

Flavor alchemy

Preserved foods are transformed through alchemical processes that yield bright, distilled flavors that shift, soften, and deepen over time. They are living, breathing things. You never know exactly what you’ll get when you open the jar or the bottle.

"[Preserved foods] are living, breathing things. You never know exactly what you’ll get when you open the jar or the bottle."

Food pros like Boulder-based Chef Colin Kirby (El Bulli, Spain, 2008) know a secret: Preserving makes foods more interesting. Done right, simple methods add new life to the most basic ingredients. For instance, savory fruits pickled with varied vinegars make inspiring elements of a complex dish. The key? They create a balance between fat and acidity, a too-often-forgotten flavor component.

Here, the minimalist chef introduces a few techniques:

White Balsamic Pickling Liquid

INGREDIENTS white balsamic vinegar: 2 parts sugar: 1 part salt: 1 part

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Red Wine Pickling Liquid

(for Cherries and Radishes)

INGREDIENTS red wine vinegar: 1152 g (38 oz) water: 535 g (19 oz) sugar: 254 g (9 oz) peppercorn bay leaf

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Apple Cider Pickling Liquid

INGREDIENTS apple cider vinegar: 2 parts sugar: 1 part salt: 1 part

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher to dissolve sugar. Let cool and set aside

Rice Wine Brine

(for Green Strawberries and Gooseberries)

INGREDIENTS rice wine vinegar: 340 g (12 oz) sugar: 340 g (12 oz) water: 200 g (7 oz) lime juice: 90 g (3 oz) bay leaf mustard seed peppercorn

DIRECTIONS Heat all ingredients to 82° C (180° F) or higher until sugar is dissolved. Let cool and set aside.

A note on processing, storage, and safety

The vinegar and spices in these recipes make all the difference. They give fruit and vegetables new life and provide inspiration to any chef. Pickling unique ingredients such as green strawberries and gooseberries gives great acidity and texture to classic dishes like duck and chanterelles.

The vinegar also allows for processing (boiling and sealing the jars to prevent spoilage) to occur, and it ensures the pH is below 4.6. This is very important. When any of these recipes are used for long-term storage, please follow basic canning rules: Sterilize jars and lids, test the pH (general rule is below 4.6), and carefully boil the jars before setting aside. Once these rules are followed, start canning. △

Recipe: Muscovy Duck Breast with Chanterelles, Pickled Radish, and Foie Gras Gastrique

A fine duck dish starring mushrooms and pickled garden gems preserved from summer. Go to recipe »

Recipe: Whiskey Preserved Apples

Bag summer a little while longer. Go to recipe »

Recipe: Alpine Hot Toddy

Enjoy a warming drink in memory of the summer harvest. Go to recipe »

Recipe: The Alpinist's Larder

A preserved whiskey drink spiked with the taste of the summer passed. Go to recipe »

Traditionally Modern

At home with Markus Meindl, the modern mountain man behind Bavaria's traditional maker of lederhosen for the new alpine lifestyle between the forest and the city.

The luxury label Meindl—known for fine, handmade lederhosen—and its CEO, Markus Meindl, deftly move between alpine costumes and fashion, between city and country, between tradition and modernity.

When he was only eight years old, Markus Meindl stitched himself a leather satchel for school. In all likelihood, the result was extraordinary and made the young lad stand out among his classmates. Today, in his mid-forties, the head of Meindl Fashions continues to stand for new ideas, for modernism, for innovation, although or perhaps because he works—and lives—for one of Germany’s best-known companies of tradition.

The urban country home Meindl built for his family near the Austrian border reflects his desire to blend modern and traditional. The minimalist house primarily makes use of natural materials, such as wood and leather, but also a lot of glass and concrete, contrasting with the row of picturesque houses across the River Salzach, on the Austrian side.

The man’s fervent passion for craftsmanship and natural materials is also at the core of the Meindl brand. Along with its traditional lederhosen, the Bavarian family enterprise has long built a multifaceted portfolio of well-crafted leather garments.

The first Meindl lederhosen

It all began when Lukas Meindl, a local cobbler in the idyllic village of Kirchanschöring in Upper Bavaria, tailored his first pair of lederhosen in 1935. Even then, uncompromising quality and the highest form of handcraft were paramount, an art form. The name Meindl dates back even farther, to the year 1683, when Petrus Meindl was officially documented as shoemaker. Markus Meindl is particularly proud of the long family tradition. After he graduated from high school, trained as garment engineer, and apprenticed as couturier, young Meindl didn’t have to be asked twice to join the family company. On the contrary. “That has always been the matter of course for me,” Meindl says. “I practically grew up in the company and have developed a passion for leather material and leather garments at a young age.”

His zeal for creating something new comes from deep within. He has always wanted to develop products he loved himself. Father Hannes Meindl gave Markus the creative freedom and the space to let his youthful zest flourish. “If I’ve learned one thing from him, it’s his free-spiritedness. His honesty in working with the product. But also his honesty in leading his employees,” Meindl says of his father.

At age seventy-four, Hannes is still actively involved in the company wherever an extra hand is needed, whether that’s in sales, in production, or in design. The traditional embroidery, however, is Hannes’s favorite component. Meindl Fashions is famous for its chamois-tanned buckskin lederhosen with lavish hand-embroidered motifs, especially in the Alps, in Austria and southern Germany with their large festivals, such as the Oktoberfest in Munich. Up to sixty hours of manual labor go into handcrafting a pair of Meindl lederhosen. The work is partially done onsite by Meindl’s 120 employees and partially at production sites in nearby European countries, such as Hungary or Croatia. “Every product is designed by us; the know-how all resides in-house,” Markus Meindl says. “We have the most talented team here, the most expensive equipment, and, most importantly, the shortest distances.”

The advantages of in-house, local production are particularly valuable in the development of new products. The Meindl company has long expanded from singularly specializing in lederhosen—albeit traditional alpine costumes are currently experiencing a revival among all ages. “Lederhosen are not a trendy piece of fashion. They span the seasons and are not merely worn to folk festivals and special occasions,” Meindl says. “Lederhosen afford reliability and a sense of security. They rise above time and represent a symbol against calamitous mass production and the consumer society.”

The new alpine lifestyle

Meindl Fashions, with Meindl Jr. at the helm, embodies that pinpoint propensity for this sensibility, the longing for tradition, and for significance. Markus has helped establish the term “alpine lifestyle” in the European Alps; at the very least he has fueled it with products that can be worn on the mountain and in the city: high-quality leather jackets, blazers, sports coats, knickers. Twenty-four years old at the time, Meindl got his breakthrough in 1994 with the creation of a collection for the rebel folk singer-songwriter Hubert von Goisern. It charged the label, the entire fashion industry. A new, modern style conquered the world of traditional alpine garments and found a home at fashion shows like Bread & Butter in Berlin.

Meindl calls his style “authentic luxury”—his own language of design that derives from the combination of craftsmanship and tradition with modern fits and cuts. “Our products are authentic yet also luxurious, because they can never be mass-produced,” says Meindl. “Out of season” is Meindl’s motto. Transcending the seasons, Meindl garments can be worn in winter or on a cool summer night, adding value to each piece.

His message rings true in a fashion world that increasingly appreciates value, sustainability, and timelessness.

Nevertheless, few people really know how multifaceted Markus Meindl truly is. For instance, he designs and produces functional and innovative motorsports clothing in very limited editions for BMW. His leather jodhpurs are worn at the Spanish Riding School as well as by mounted police in Germany. His cousins run the local shoe manufactory, which makes quality mountain footwear and traditional costume shoes. A diverse product portfolio has always been the brand’s strength.

Country refuge for an urban mountain man

Quality stands above all. Timelessness, longevity—and Meindl sought to embody these values in the design and construction of his private home. “I’ve thought long and hard about how I want to design the house,” he says. “It was supposed to withstand time and still be as attractive twenty years from now as it is today.”

His friend Robert Blaschke of Raumbau Architekten in Salzburg, Austria, realized the project. Wood wherever you look, heated Swedish oak floors. Ceilings and walls are covered in 300-year-old oak wood reclaimed from Bavarian barns. The 3.9-meter-high (almost 13 feet) ceiling in the living room and the ceiling in the spa are lined in wooden cubes. The same element serves as armoire and shelving units in the living room and along the facade. The length of the pool—16.83 meters (55 feet)—reflects the year the Meindl company was born; a whimsical reference to tradition interrupted by modern elements. Tradition, lived modernly—that is Meindl’s philosophy. “I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things,” Meindl says. “But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time.”

“I grew up here in the mountains. I respect the traditional way of life. I love simplicity, the value of things. But I am not a conservative man. You have to continue to develop things further, keep playing with things. That’s the only way tradition stands a chance of surviving over time."

Markus Meindl regards himself an “urban mountain man” who lives between the antithetical realms of an urban and a bucolic world. You work in the city during the week. And on weekends, you live in the mountains, where you go skiing, go hiking. “Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.” △

“Clothing has to work for a meeting in the city but also be functional in the mountains and in the woods. In all of life’s circumstances. That’s the language Meindl speaks most clearly.”

More from Meindl's collections...

Alpine Modern in Its Natural Habitat

Behind the scenes at the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 lookbook photoshoot

We packed up the entire Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Collection and headed up Flagstaff Mountain in Boulder, Colorado.

We stopped halfway up the gorgeous, winding road to the summit. The secluded spot overlooking the city was the perfect place to set up for the shoot. Our good friend Garrett King (@shortstache) behind the lens, and another good friend, talented designer and illustrator Adam Sinda, modeling.

We wanted to capture our Alpine Modern Summer 2016 collection in the most natural and minimal form in which the products were designed and intended to be used. We didn't need a fancy backdrop or expensive studio. We "worked" in Boulder's beautiful backyard.

The goods we design and craft are all about elevating your life. Our mission is to bring modernism to mountain style. From our organic tees and versatile hats to our leather bags coated in an oil finish to repel the elements — our goods are crafted for the mountains but also for daily use and wear. △

More from the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Lookbook...

The Fragrance of "Out There"

A harvest walk on the wild side with the wilderness perfume crafters of Juniper Ridge

Hall Newbegin is out there. Upon first meeting him, I didn’t expect it. He seemed jovial, unintimidating, and mild-mannered. But in the first five minutes of our conversation he used the phrase “out there” eight times — “Part of what I wanted to do was to just be ‘out there’ . . . Being ‘out there’ just centered me . . . Being ‘out there’ saved me as person . . . I had no idea where this was going, but I loved being ‘out there.’ ”

Return to the wilderness

All of us go through periods of discovery in our lives when we are searching for direction, trying to find out what defines us and how it can drive our life and work. For Newbegin, the founder and head perfumer for Bay Area-based Juniper Ridge, that discovery came after a stint on the East Coast and a return to his roots in the West, a return to the wilderness — “out there” — where he feels most comfortable and alive.

Newbegin never imagined that being “out there” would lead to a burgeoning fragrance business, with his products sold in outlets around the globe. He stumbled upon the idea after trial and error — in his life, in his passions, and in his own business.

Capturing the essence of being “out there” is the driving force for the people who run Juniper Ridge, which proclaims itself the world’s only wilderness fragrance company. Headed by Newbegin and the firm’s chief storyteller and packaging designer, Obi Kaufmann, Juniper Ridge, per its website, is “built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

“Built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

Newbegin and his team embrace this mantra through a process called wild harvesting, where they make real fragrances from the places they know and love — the trails of the rugged and diverse American West.

Their teams of hikers crawl through mountain meadows, smelling the earth, the wild flowers in bloom, or the moss covering the trees, then harvest the ingredients to capture the real scent of that land. Armed with public permits or private permissions, they gather wild flowers, plants, bark, moss, mushrooms, and tree trimmings, then distill and extract fragrance by employing ancient perfume-making techniques of distillation, tincturing, infusion, and enfleurage. These formulations vary yearly and by harvest, due to rainfall, temperature, specific location, and season.

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive.”

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive,” says Newbegin, whose Instagram handle is @crawlonwetdirt. Yet this call to the primitive is based in fact: Our sense of smell is often called the oldest sense, the only one with a direct connection to the brain. That connection brings pleasure and sparks memory, transporting us in time and place. For the team at Juniper Ridge, the time and place is marked on every bottle of fragrance they sell. In fact, they authenticate the process of each harvest by stamping each package with a harvest number and by documenting the process through an accompanying story and photographs on the Juniper Ridge website.

“Our muse is the place. And our job is to funnel that the best we can,” says Newbegin, pointing to a small spray bottle of Sierra Granite, a fragrance connected to California’s Sierra Nevada. “Everything in this bottle is real. Our test is always ‘Is it the real place?’ ” Some of the other places they have captured include Big Sur (California coast), Siskiyou (Oregon coast), Mojave (Mojave Desert), and Cascade Glacier (Oregon’s Mount Hood).

“Our muse is the place."

Real fragrance resonates

Kaufman notes that as the business has grown, sales have been strongest in Scandinavia and New York City. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, it takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us,” he says. “Ninety-nine percent of the people who buy this have never been to the Mojave Desert, but because it’s real fragrance, it resonates — this is real, it’s not Comme des Garçons, it’s not that bullshit stuff at the Nordstrom’s counter that’s made from petroleum, and that never existed on earth until ten seconds ago. Because this is real, it goes deep into our genetic past — we’re responding to something real.”

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, [the fragrance] takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us.”

Saved by the wild

While hiking on Marin County’s Mount Tamalpais with the sometimes loquacious but unassuming Newbegin in his worn T-shirt and jeans, it’s hard to imagine that he would describe the transcendent moment of his life as a cliché. But those are the exact words he uses when he muses on the importance of the wilderness and the outdoors: “I feel like it saved my life.”

Growing up in Oregon, with Mount Hood in his backyard, Newbegin spent most of his youth hiking and backpacking. He attended college in New York but knew there was something growing inside of him, “a hunger to get back to the West and be in the mountains . . . I had camping and being outdoors in my blood. It’s a deep West Coast/western cultural thing,” he says.

With a last name like Newbegin, it seemed inevitable that he would eventually find his true calling. That happened in Berkeley, California, after a period he deems his “hippy schooling.” He took inspiration from eco-wilderness writers including Gary Snyder, John Muir, and David Brower and studied under commercial mushroom harvesters, members of native plant societies, and herbal medicine teachers.

New beginning

The real turning point came as he was foraging native medicinal plants in the Sierra Nevada. “I dug my trowel into osha root, and the air just exploded with that smell and it’s like, ‘ahhh.’ It would just slay me,” he says. “I didn’t know what the stuff was. I wasn’t thinking about fragrance or anything. I just loved being out there. It just centered me. It brought me into this world where the big thing is there, and it just brought peace over me. You’re looking at plants, at trees, your map, and you smell the ground and suddenly it breaks. You’re just there. All that chatting in your brain just stops, and you’re just there.”

This was the beginning of an epiphany, but the path from being an outdoorsman to becoming a true perfumer has been sixteen years in the making. “You know how journeys are,” Newbegin says, “You just start taking your steps, and soon you start getting somewhere. And so, I started learning how to extract goo out of plants. I was going to the Berkeley Public Library and trying to figure out the old extraction techniques of how you get the goo out of the plants.”

Eventually, he was mixing that goo with other ingredients to make soap and selling it for four bucks a bar at the Berkeley Farmers’ Market. He describes encounters with his first customers: “They would say, ‘Oh my God, this is Big Sur in a soap.’ ” Sounding a bit like Hemingway, he would give them the authentic story of the day that it was harvested — “I got black sage goo on my arms, and I took a nap under this big black sage shrub and had dreams about it and woke up, and the sun was on my face, and the air was just filled with the cleanness of black sage and bees in the air.” Their response, according to Newbegin: “OK, I’ll take ten of those, right now.”

Goo business

After quickly selling out of his product, Newbegin also realized that he was vastly underpricing his offerings. Over the years, he and his team have refined not only the process to get very consistent quality, they have also learned how to price their product to create a sustainable business. Newbegin laughs when he says, “We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.” And yet, it is a business that is working — with retailers such as Barneys New York now carrying the product, and outlets as far away as Paris, Moscow, and Tokyo.

“We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.”

And Newbegin’s enthusiasm for his product and the process is still very evident. “When I hand this to someone, I think to myself, ‘Oh, my God, you’re getting something just unbelievable.’ All that green in there . . . This is what Mount Hood was like as of September fourth of last year. All that green goo, tree pitch. It’s just real. It’s just 100 percent real.”

The Juniper Ridge team talks about how this realness is a stark contrast to the more synthetic nature of traditional perfumes. Those classic perfume houses employ someone who is called “a nose” to help them create unique fragrances. Globally, there are around fifty “noses” who are highly sought after for their olfactory abilities.

Although this is rarefied air that Newbegin wants no part of, he does refer to himself as “the Pied Piper of the nose.” He is quick to recall the power of the sense of smell. “My message is, use this primitive thing because it will change the person you are.” The scent of nature “is everywhere, all the time. So wake up your sense of smell,” he exhorts. “I want people to do it, not because they should, but because it’s the most sensually gratifying thing they can experience. It’s wonderful.”

Try for yourself

Newbegin’s final piece of advice: “Do what we do — get outdoors, crawl around on your hands and knees, smell the wet earth beneath your feet. Or if you’re worried about embarrassing yourself (which you should be since people don’t normally crawl around on trails), just start by crushing tree needles and plants under your nose. Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.” △

"Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.”

Dwell × Alpine Modern

We are incredibly excited to announce our partnership with Dwell

From the very beginning, as we imagined Alpine Modern to be a publication about modern architecture, design and elevated living in the mountains around the world, telling people about our vision has usually included something like "You know, like if Dwell and Cereal magazine had a lovechild in the mountains..." Dwell's authority in showcasing international modern architecture and design has inspired us in our own work. This is why we are incredibly proud to announce that today marks the beginning of our partnership with Dwell.

This means, you will see some of our editorial stories on the new (launched today!) Dwell.com, published under the banner of Alpine Modern. What's more, we will present Alpine Modern "Curations" — a new element of the redesigned Dwell.com. This can be anything from a product roundup from the Alpine Modern Shop to a themed collection of stories about cabins, art and journeys in Norway.

In return, you will read cherry-picked Dwell content on Alpine Modern Editorial.

Follow @alpine_modern along on Dwell.com as Dwell and Alpine Modern together kindle a longing for elevated living, through slow storytelling, amazing photography and tightly curated alpine-modern objects. △

Utahan Utopia

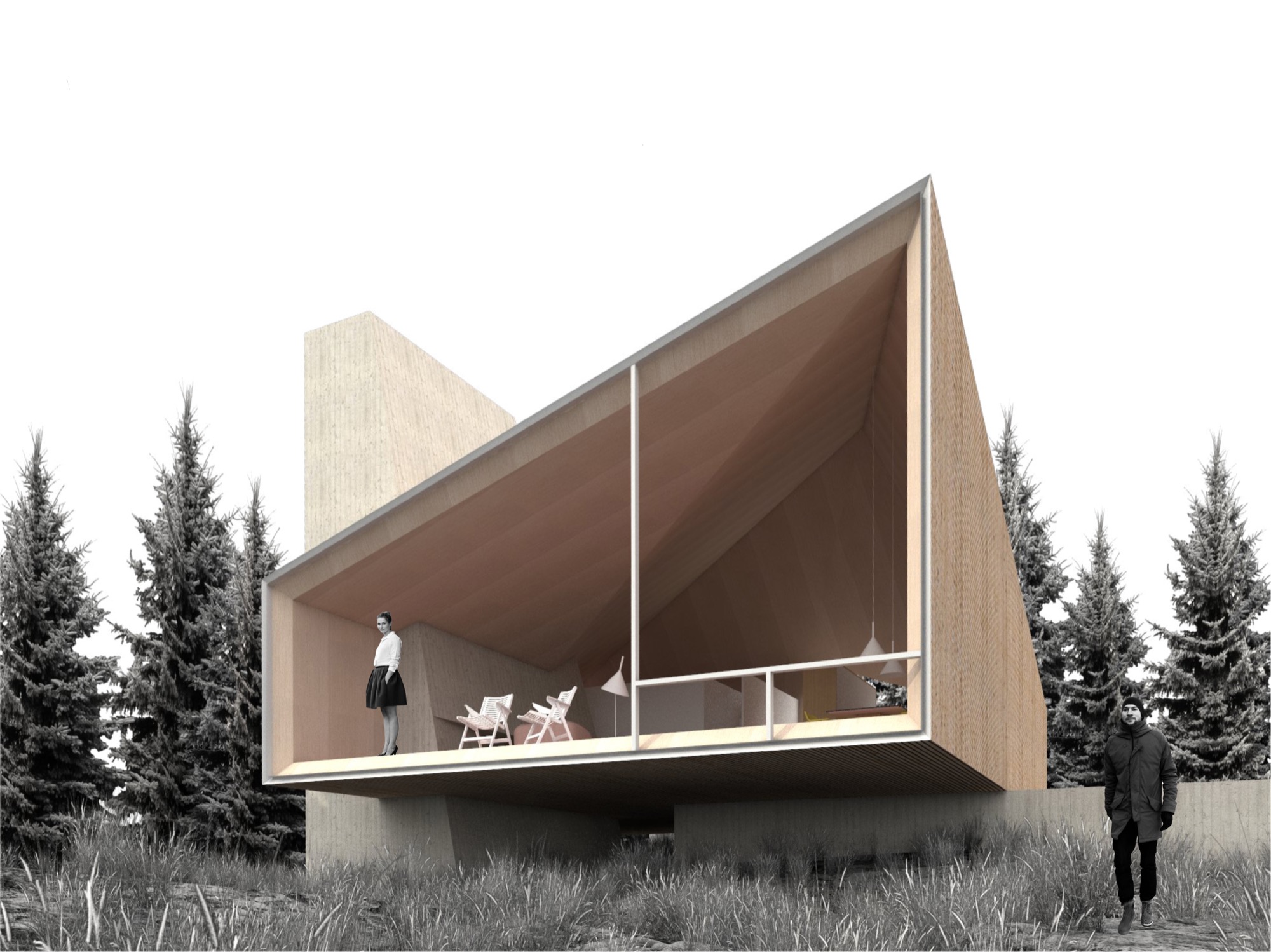

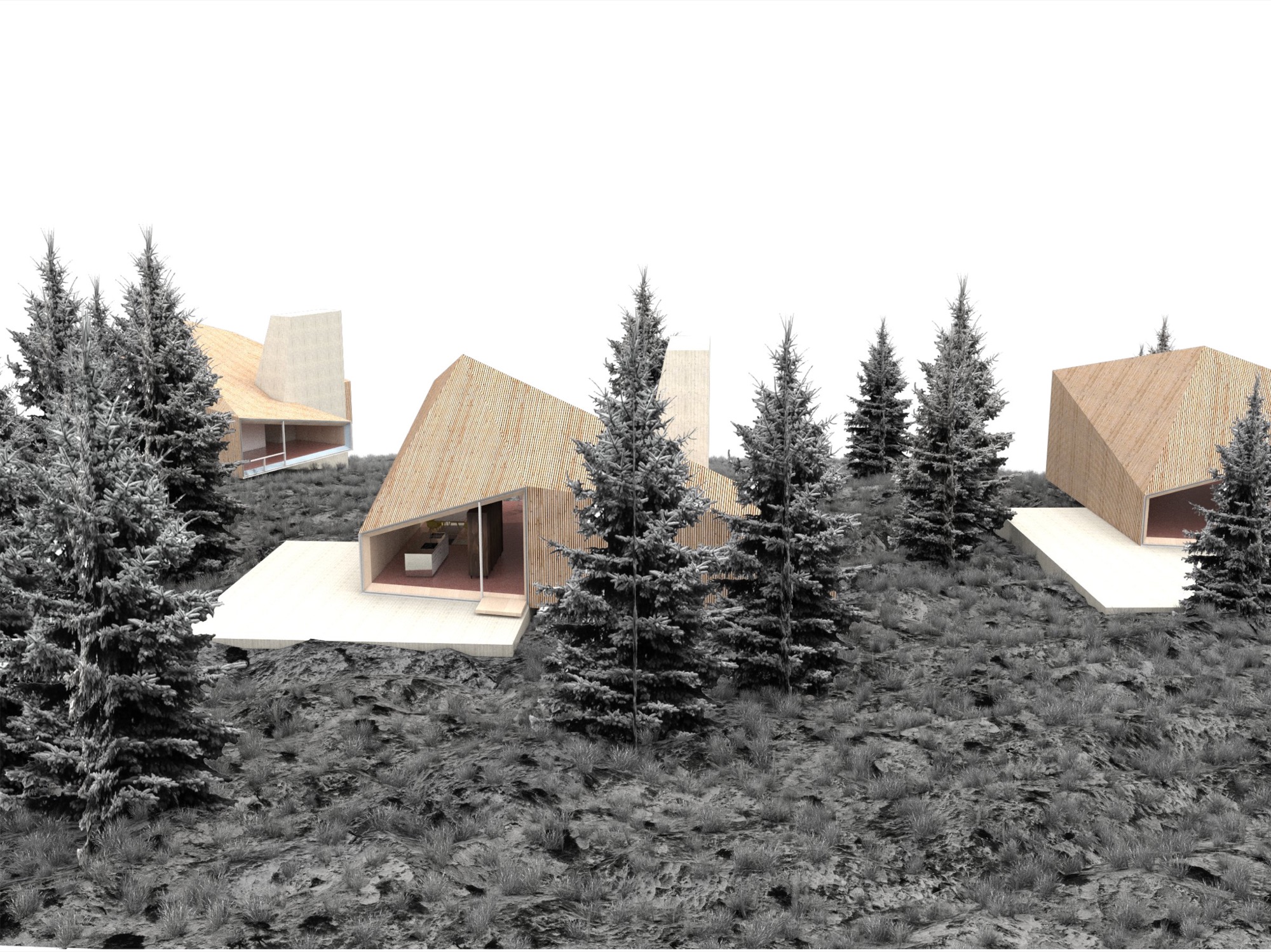

Summit Powder Mountain in Utah is a visionary colony of cabins designed by emerging Slovenian architect Srđan Nađ

A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the conversation on nature-respecting modern mountain architecture and communal living on Powder Mountain, where an enigmatic group of entrepreneurs, creatives, and altruists is building a pioneering alpine village. “We bought a mountain.”

So begins the backstory of Summit Powder Mountain, a visionary colony of cabins and an alpine village being dreamed up in Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

Elliott Bisnow and the Summit Series

Behind the idea is Summit, an event business started by Elliott Bisnow, a founding board member of the United Nations Foundation’s Global Entrepreneurs Council. What began as a small gathering of a few dozen investors, business whiz kids, and creatives over a short few years grew into the Summit Series: traveling invitational events that summon hundreds of thought leaders and different-thinkers from around the world. "What would it look like if Davos and Burning Man had a baby?" The Guardian rhetorically wondered in a recent article about the Summit Series. For its latest flagship event, Summit at Sea, 2,500 chosen attendees boarded a cruise ship in Miami for a four-day conference in international waters.

Rooting down in Utah

Now Summit is building a permanent base camp for its forums—a high-alpine town for its growing tribe to come home to. Summit purchased Powder Mountain, including the ski resort that has been operating there since the 1970s, with the vision to fundamentally reimagine and experiment with how people live together, shelter themselves, and converge for the greater good. “I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world,” says Summit design director Sam Arthur, who moved to Utah to see the project through. Since buying the mountain in 2013, Summit has called on sundry architecture and design gurus, even sacred geometry to conceive this test bed for communal living. But the group still needed a cohesive cabin concept, a trademark design that considers the demands of living at 8,400 feet (2,560 meters) altitude, of building sensibly on historically mostly undeveloped, pristine mountain land that includes an elk reserve, natural waterways, and thriving wildlife. A sheep ranch was the only settlement on the mountain for the longest time.

“I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world.”

Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition

Thus, Summit’s Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition challenged the global guild of architects, engineers, artists—masters and students alike—to design sustainable cabins that embody the leadership’s ideals of sustainability, use of natural materials, and humble expression. The winning concept would guide the architectural ethos for more than 500 single-family homes, limited to 2,500 square feet (232 square meters) on half- to two-acre lots. Arthur says they capped the size of the homes so Summit Powder Mountain could become a democratized, harmonious environment for the community at large rather than “this über-wealthy place that is about showing off how big and bad you are.” Larger lots of up to thirty acres, however, could potentially accommodate a compound design.

Choosing a winner

The winner: Srđan Nađ, a young architect from Slovenia. His prized design was inspired by a Summit event photo he had seen—a green meadow dotted with simple white tents, pure architecture integrated within thin cloth, pitched to create shelter from weather and wilderness. His other muse was the frontier cabin of America’s past, a simple wooden structure with a great stone chimney on the outside. “Combining both was my design concept for Summit Powder Mountain—a true connection with nature,” says Nađ, who believes “95 percent luck” won him the competition. More likely, though, he convinced the international jury panel, led by Todd Saunders of Saunders Architecture (Norway) and Jenny Wu from the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles, California), with his design’s adaptability and transformational potential. Arthur says, “Srđan did a beautiful job of meeting the criteria and applying a certain amount of aesthetic to it that really eloquently resolved that future/nostalgia-heritage/modern friction, which is at the core of what people respond to here, how they want to live in the modern age.” With its indoor/outdoor quality and what Arthur describes as “an obsession with light and views,” Nađ’s design captures the raison d’être for living on a mountain. “It’s a place to find refuge, to be inspired, to take in the natural primary source of beauty, and recreate with friends. It’s often very difficult to turn that into architecture, but Srđan took that and wrapped a building around it.”

Who is Srđan Nađ

Born to two architects in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1983, Nađ’s career choice was perhaps destined by birth. He attended a special building and engineering high school and spent his senior year abroad in upstate New York. He returned to Europe to study architecture at the University of Ljubljana, which he describes as a “boutique school” in the center of the city. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of architectural competitions and really test my ideas—and, of course, learn from my mistakes.” After practicing the craft with other studios for several years, Nađ founded Grupo H with his wife, a landscape architect. Based in Slovenia and surrounded by mountains and the outdoors, the company is dedicated equally to architecture and interdisciplinary aspects of planning and building.

“I grew up in Dubrovnik, Croatia, a great historic town by the Adriatic Sea, so I didn't have any understanding of the alpine world until my fantastic wife, a local Slovenian girl, introduced me to the alpine world of Slovenia and its natural environment,” Nađ says. “What’s special about Slovenia is that the mountains here are relatively inaccessible, and to get to know them, you need to hike a lot. Hiking is a local obsession here.”

Living in the small European country known for its mountains, outdoor recreation, and ski resorts—much like Utah—has transformed the man from the seaside. “When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective,” says Nađ. “It teaches you to admire and respect the wild nature of the alpine world. In the end, when you are put into the position to design a building for such a surrounding, all your knowledge and memories come together to create this unique combination of simplicity and elegance that a building high in the mountains demands.“

“When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective.”

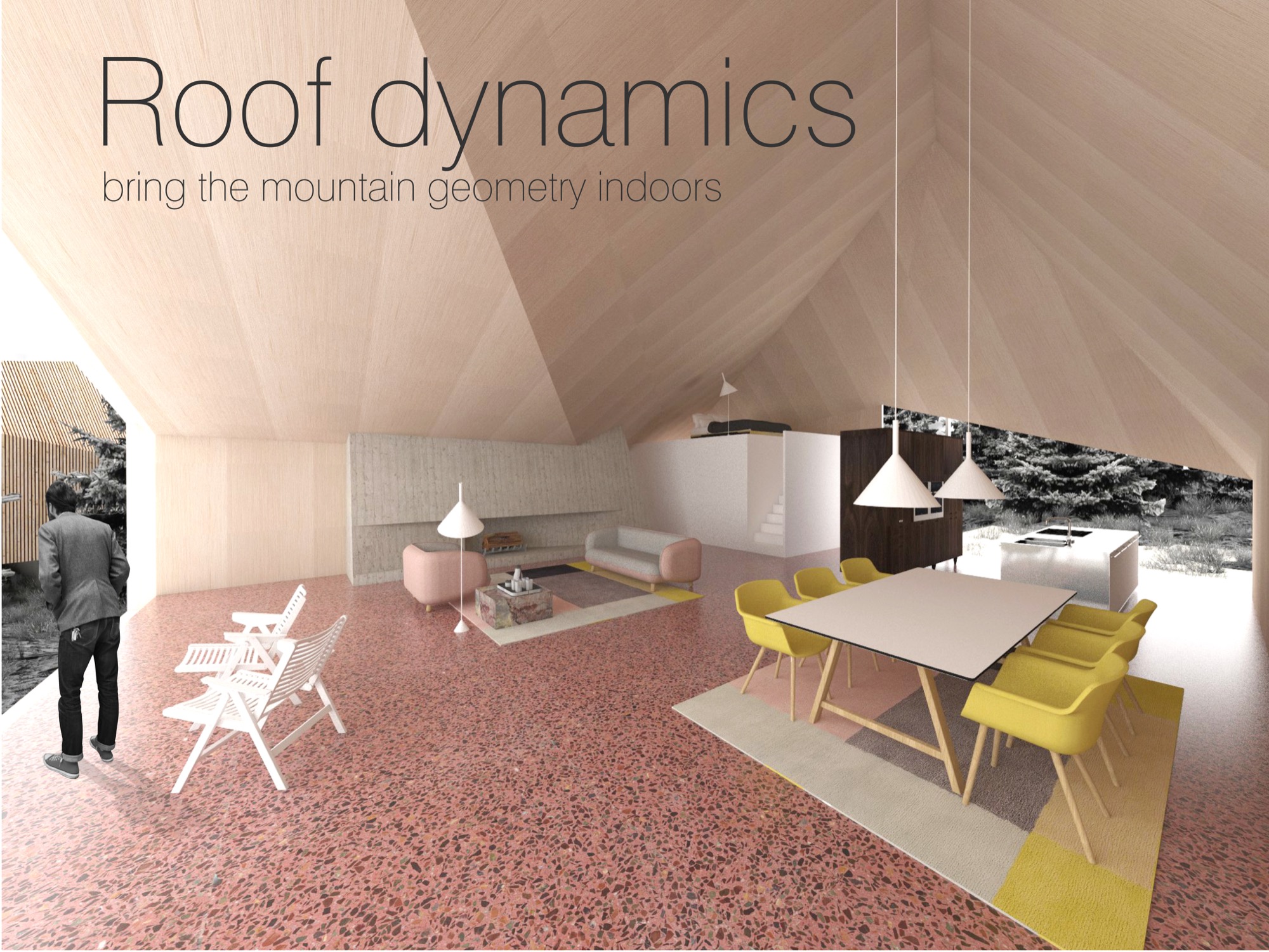

Nađ's "Wooden Tents"

His proposed cabin design preserves that tentlike lightness and unmistakable functionality that inspired him and manifests it in a permanent, habitable structure. The architect expresses this lightness through a 1.5-inch (3.80-cm) thin “skin” made from cross-laminated prefabricated wood panels, folded to create the interior space of the cabin. This folding process leaves open the sides, which are then covered in glass. Juxtaposing the transient openness of the folded skin, a monolithic stone chimney stakes the raised cabin, grounding it into the mountainside to create the permanence a tent lacks. The chimney’s body also houses the mechanicals. On the opposite side, the cabin leans on a deck that touches down to the ground. With only the chimney and the deck as supporting elements, the cabin’s footprint is small, making large earth excavations unnecessary. The triple-glazed glass walls let the sun heat the highly insulated interior. Rainwater from the sloping roof collects into storage tanks under the deck. The goal is for the cabins to be certified according to the European passive house standard and the American LEED standard.

The cabin design allows for different versions of the prototype, varying from a simple one-bedroom hut to a luxurious four-bedroom chalet. The blueprint foresees an open living/dining/kitchen area with a large fireplace. The high ceiling follows the geometry of the exterior roof, mimicking the surrounding mountain silhouette. “In all, it will be a fantastic place to come back to after a full day of skiing or a long summer hike,” the architect hopes.

Nađ’s minimalistic “wooden tents” are designed to serve as fully functional habitable structures without creating the feel of urban settlement on Powder Mountain, and they preserve the essence of the natural surroundings. Nađ strove to convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out your private piece of paradise.

His sensible solution was, no doubt, spawned by his home country and culture. “We are really humble, hardworking, and resourceful people. So that guides me to find simple, functional, and long-lasting designs for my projects,” he says, adding that the alpine cabins and shelters of the Slovenian mountains influenced his “wooden tents” for Summit Powder Mountain. “They are simple, rugged, but still graceful in unforgiving nature.”

Nađ didn’t plan to enter an architecture contest at the time he learned about the MAP design competition on an architecture blog. But the subject—a cabin—intrigued him since he thought it rather uncommon for an international contest. “You usually have a competition to design a museum, library, memorials...but houses are rare.” The premise of Summit Powder Mountain eventually compelled the young architect to enter his design. “You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.” However, he didn’t grasp the expanse of the project until he spoke with the Summit team. “I didn’t realize how important this is for the global community, as it shows a new way of planning large developments,” he says in retrospect. Nađ understood that no matter how good his cabin design was going to be, simply copying it 500 times would only create the type of cookie-cutter development that already characterizes too many mountain resort towns. “My design goal was to create a house that can be transformed—enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, have a different facade—and still preserve the overall design idea,” he explains. The “wooden tent” concept is a suggestion, one Arthur says is “a loose design that’s poetic and evocative.”

“You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.”

Building community