Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

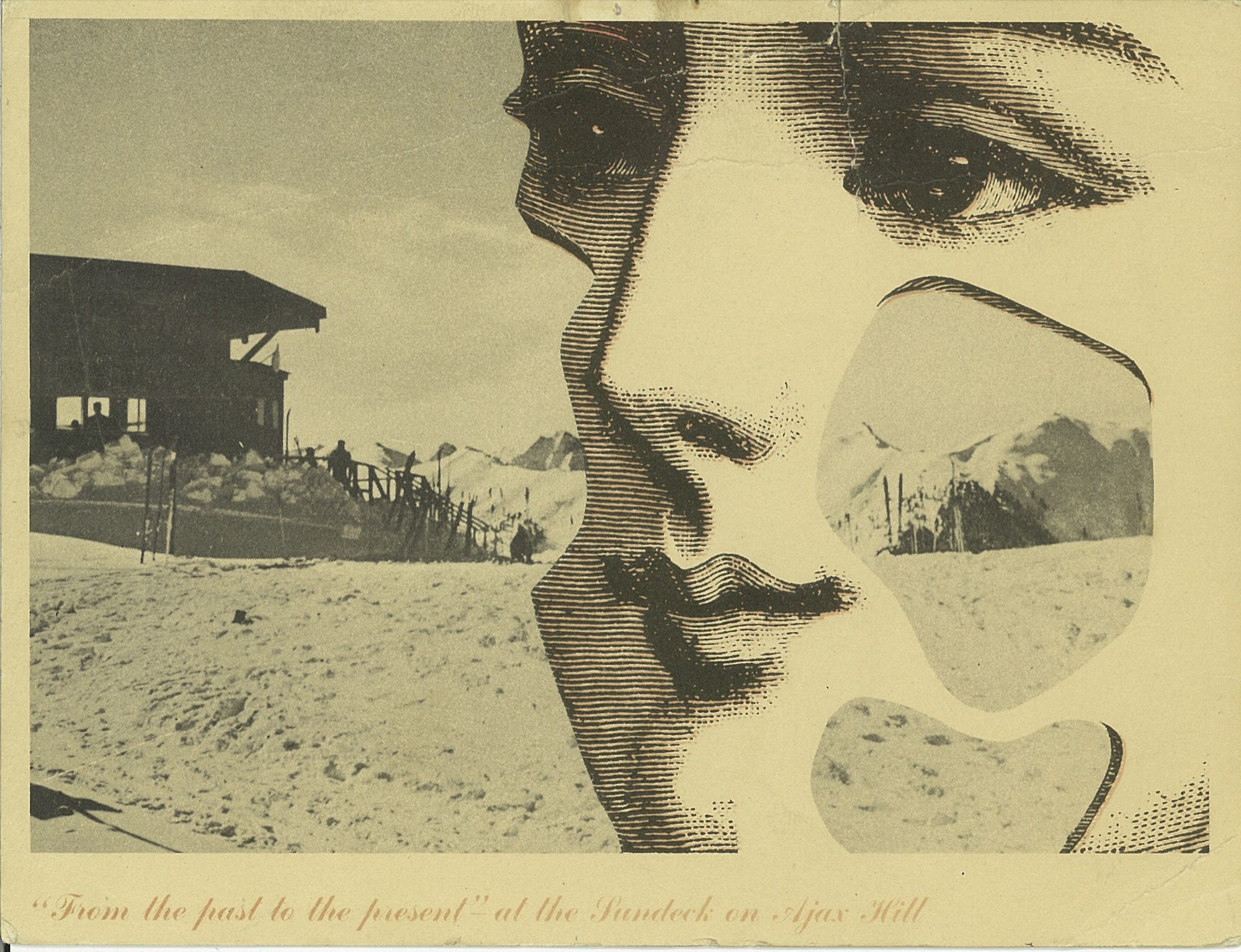

How American Modernism Came to the Mountains

A daughter of America's midcentury-modern movement remembers how Chicago’s design elite settled in Aspen, giving rise to modernism in the mountains of the West.

After World War II, Chicago’s design elite flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, galvanizing the then-sleepy alpine village with modern mountain chalets and avant-garde public buildings that helped transform Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley into the glamorous destination it is today. A memoir by artist Marcia Weese, daughter of Harry Weese, a central figure in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern.

Someone recently remarked to me that I was “born to design.” Over the years, I have come to appreciate this birthright, as I realize I have tenaciously and (mostly) joyously cleaved to the creative life, and still do. I have my parents, Harry Mohr Weese and Kitty Baldwin Weese, to thank for this. The creative life is not for the faint of heart, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Childhood in Chicago

It was the early 1950s in Chicago. As my mother told it,

“The war was over. No one had any money. No one had any furniture. Apartments to rent were scarce. We made do.”

When I was very young, we lived in a dim railroad flat in downtown Chicago. This was a typical inner-city apartment with a linear floor plan. The only natural light filtered through windows in the front and back. Chicago was a coal-burning city, and you could write your name on the window sills in the soot. I remember running down the dark hall that connected front to back, with crayon in hand. My parents encouraged my sisters and me to draw on the walls in that nondescript hall. What a great idea they had to spruce up the crepuscular gloom of the hallway, and how fun it was for us to break the rules.

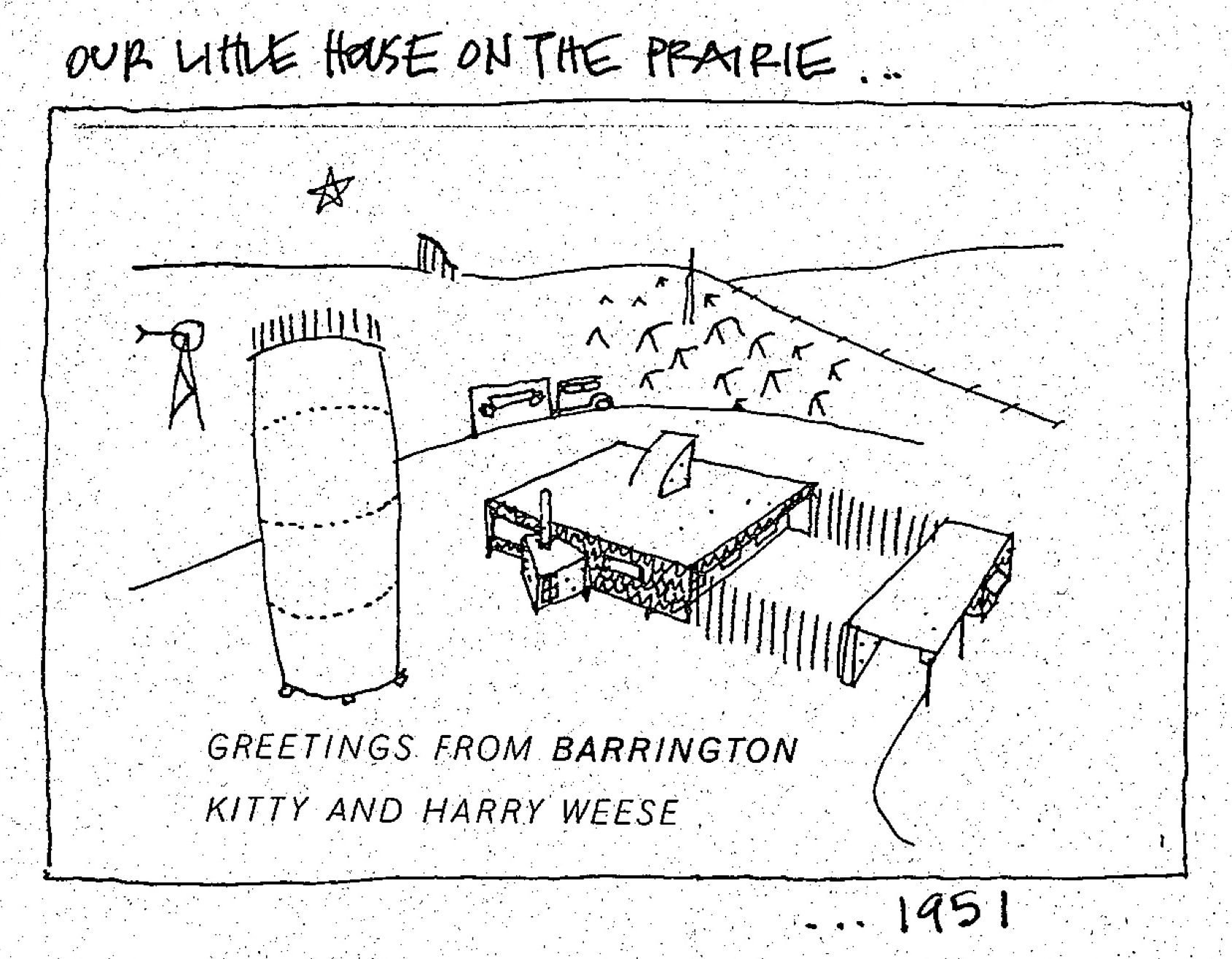

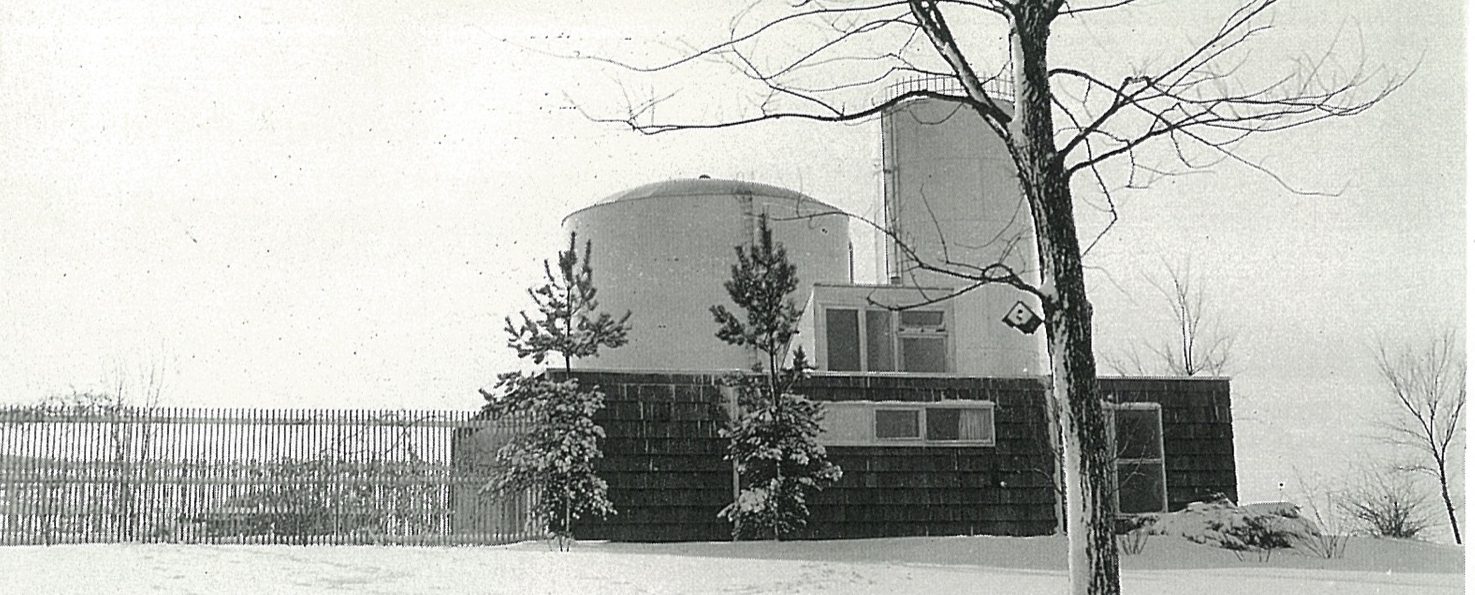

We spent weekends and summers in the country forty miles northeast of Chicago. Now it is wall-to-wall suburbia, but back then, we bundled our five-person family, one cat, two turtles, and several guinea pigs into the car and drove (pre-Kennedy expressway) through many stoplights to the little town of Barrington, Illinois. There, we lived in one of my architect father’s early houses. Built on a lot adjacent to two immense water towers belonging to the town, the house was modern and modest; a one-story house with a flat roof, carport, gravel driveway and a fenced-in garden the three bedrooms emptied into. It was sparsely furnished, and I will always remember the black-and-white linoleum floor. Mom found some dinner-plate-sized checkers pieces and we played checkers on that floor to our endless delight.

Some years later, my grandfather gave my father a nearby five-acre (two-hectare) plot of land, which consisted of a hill, many large oak and hickory trees, poison ivy everywhere, and a hand-dug lake topped off with a pet alligator. Here, my father built a wonderful and quirky house (prebuilding code) he named “The Studio.” We spent many years toggling between city and country. This was a refuge from the city for my parents, and for me, a secret garden of woodland flora and fauna.

Studying with the Eamses & Co.

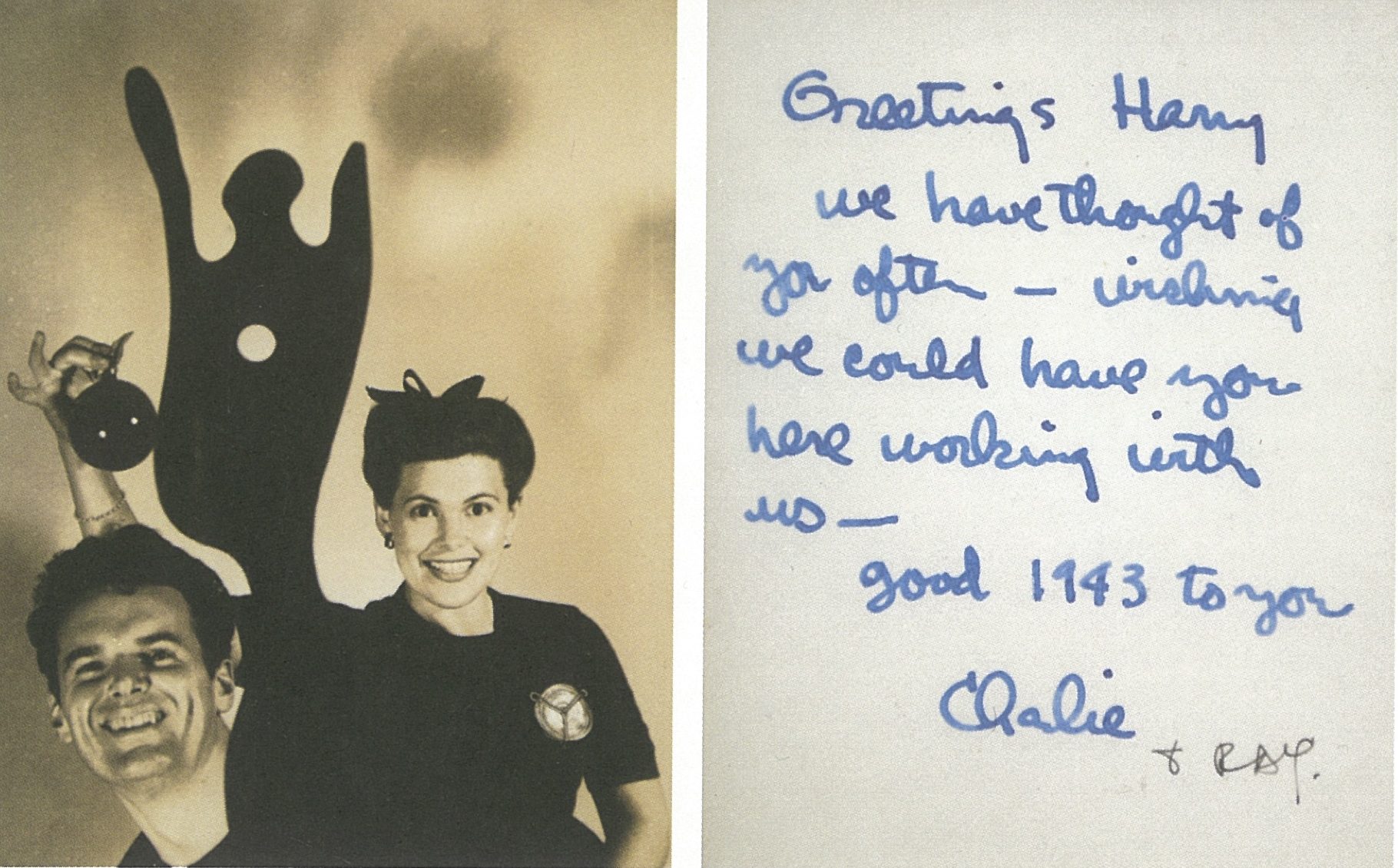

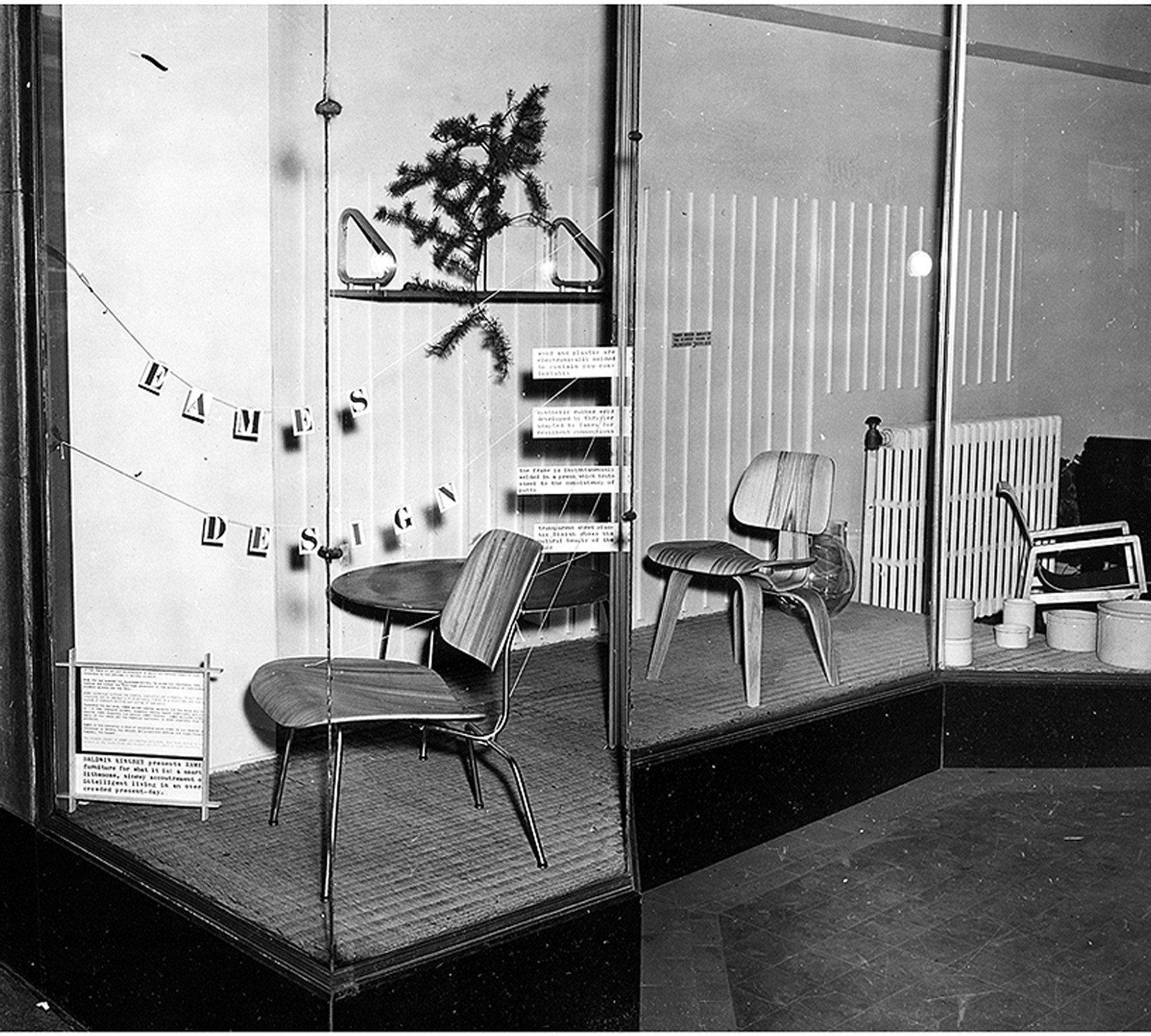

After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in architecture and engineering, Dad studied in Michigan at the Cranbrook Academy of Art with Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ben Baldwin, and a host of others who were living and creating modern design at a time when the atmosphere was ripe for it.

As history has revealed, many became household names, even demigods, in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern. These people were some of my parents’ closest friends.

My father and Ben Baldwin had won a few industrial design awards from the Museum of Modern Art while at Cranbrook, so they decided after graduation to “hang a shingle”—Baldwin Weese—to practice architecture in New York City. They worked together for a year but decided to convivially go their separate ways; Ben stayed in New York, and Dad returned to his birthplace, Chicago. But first, Ben introduced my father to his sister Kitty.

When Harry met Kitty

As my father approached the house to meet Kitty for the first time, she watched him jump over the fence rather than use the gate. That did it for her. He was a nonconformist, an inventor, a man who loved to use the path less traveled. He had no use for convention as it was, in the post WWII era. The overriding spirit was “rebuild,” therefore “build anew.” This was the perfect time for him to launch his architectural career in Chicago. He founded the architecture firm Harry Weese & Associates, which lasted for fifty illustrious years. My mother, who was southern, elegant, and graceful, was over the moon for this artistic, restless spirit. Not a typical match, but it worked; he needed her organized calm and “good eye for design” to manage his ambitions.

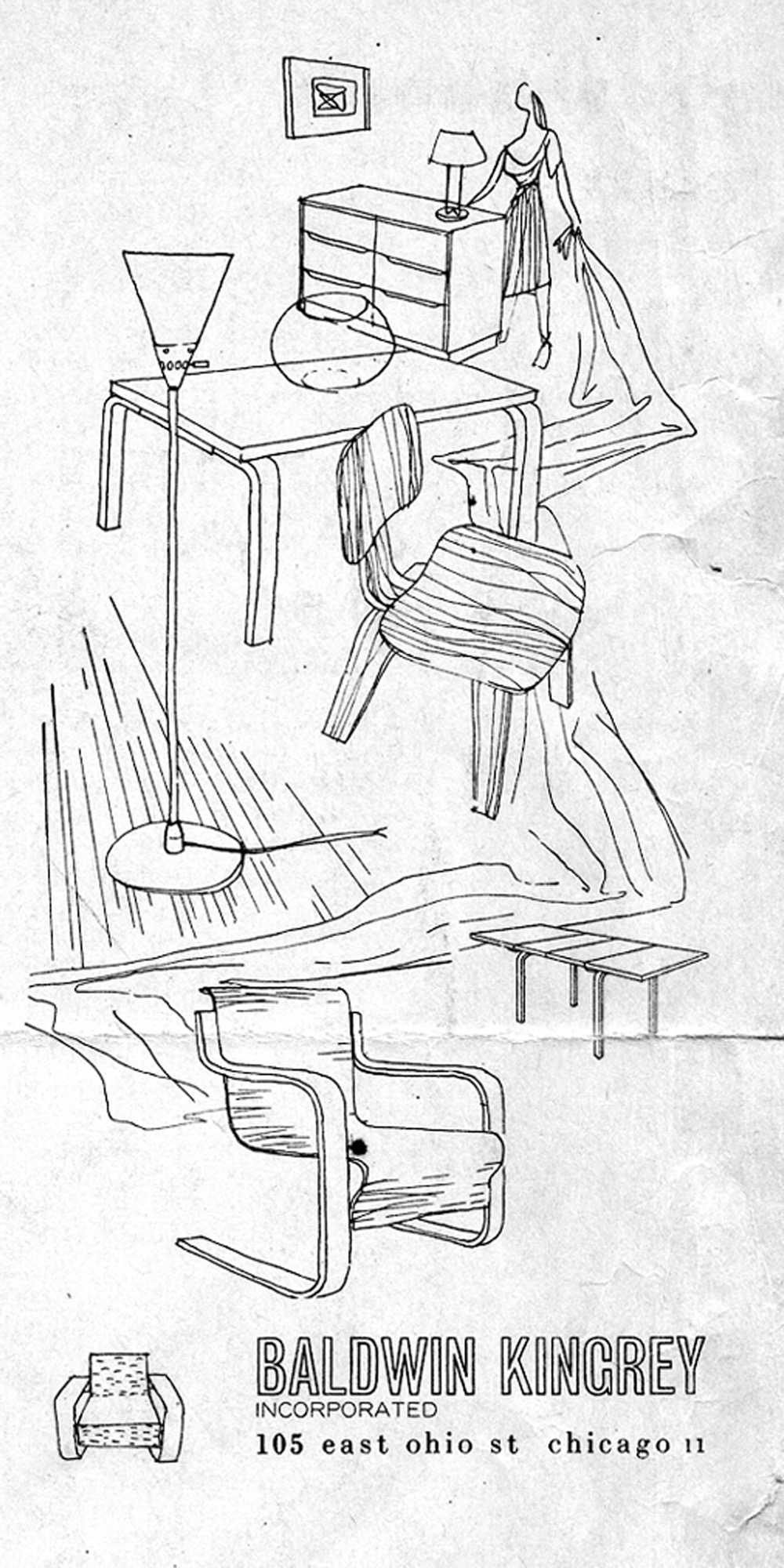

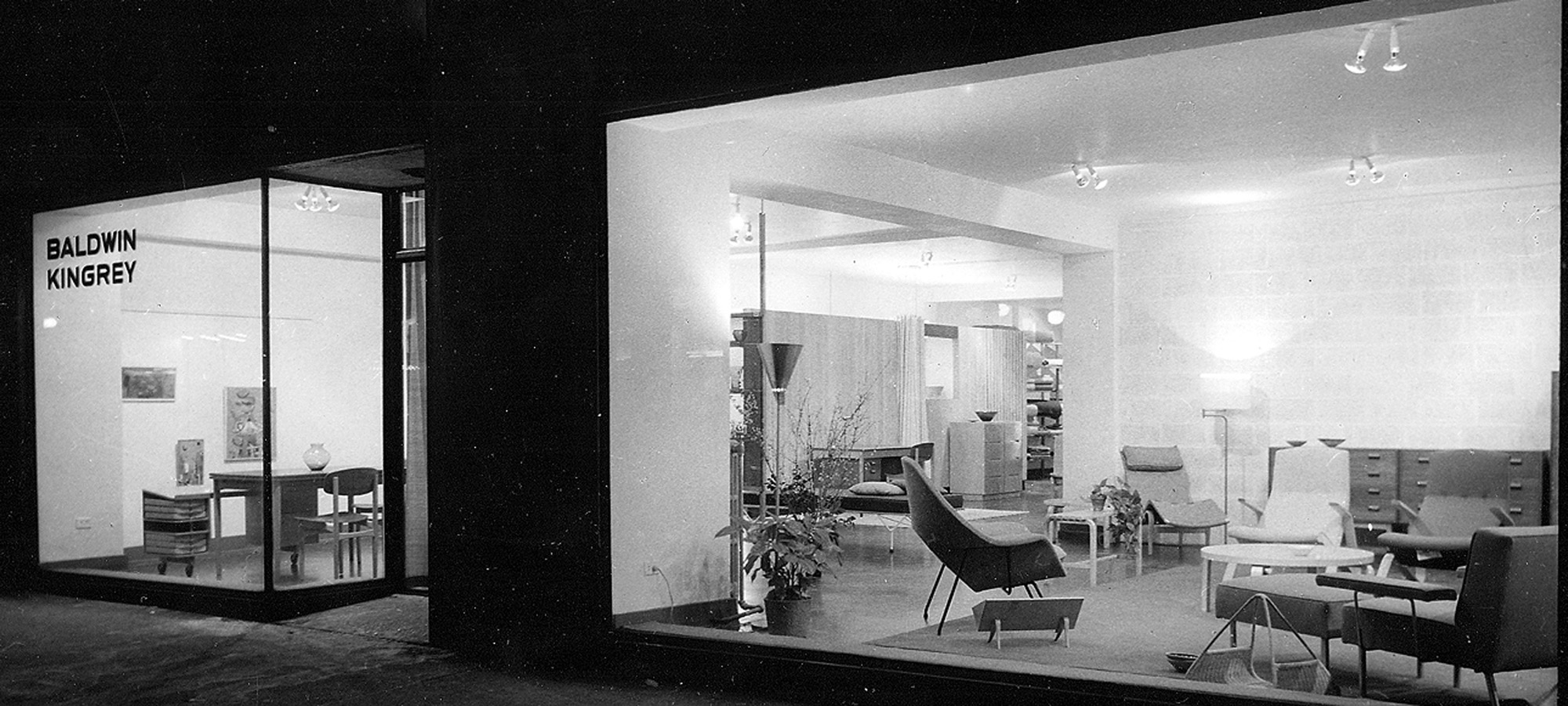

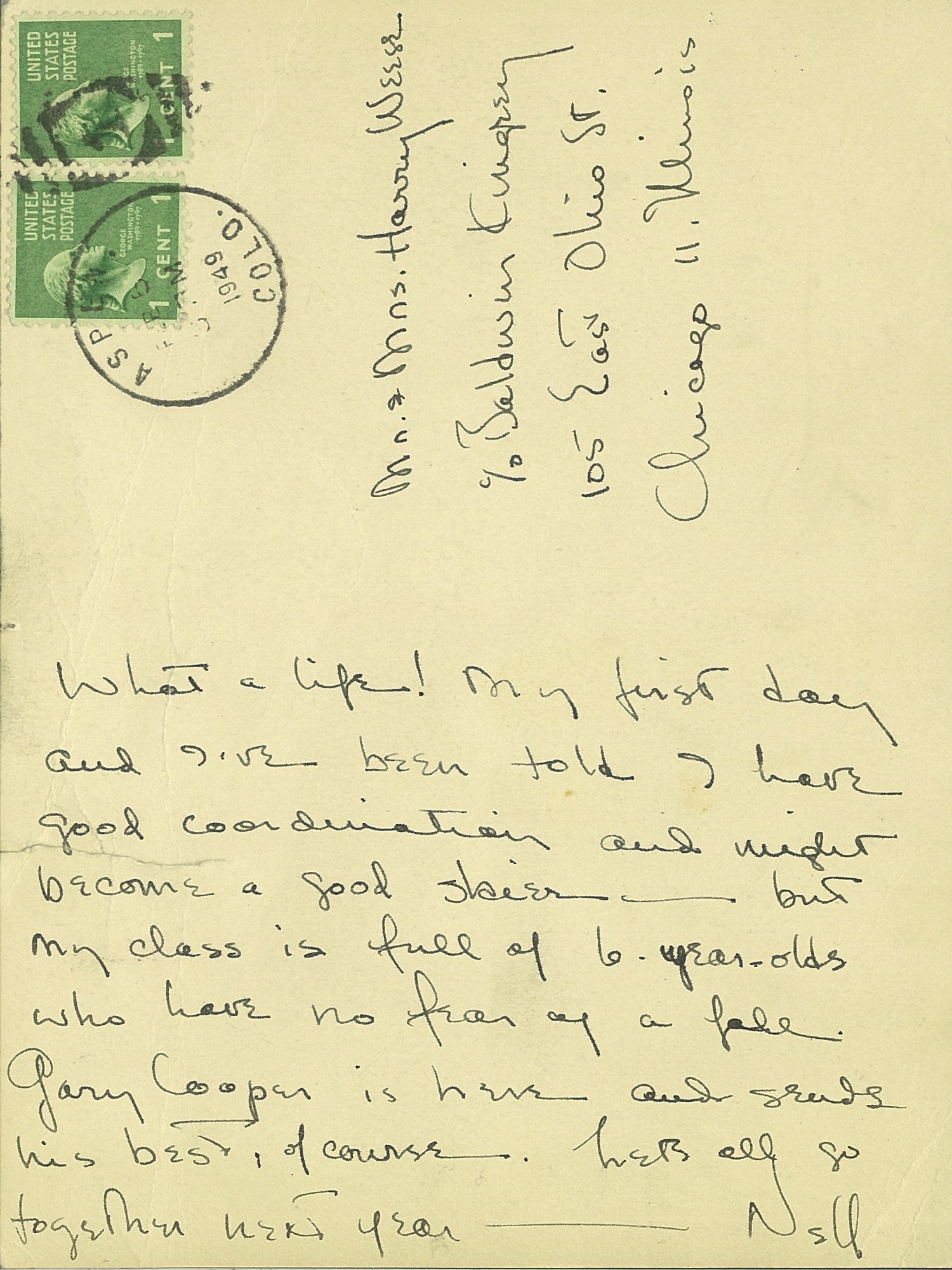

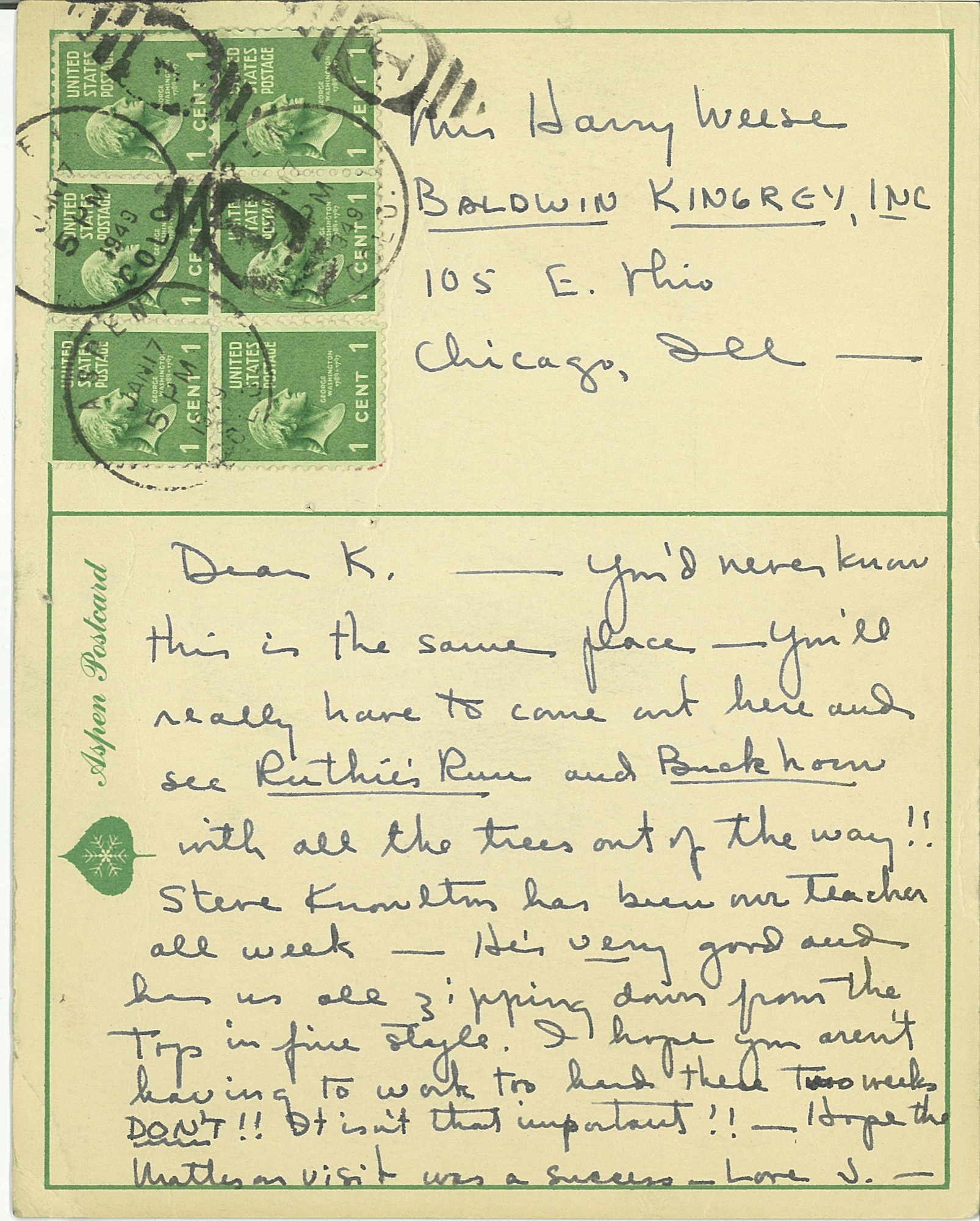

Baldwin Kingrey store in Chicago

In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father. While in the navy for three long years he kept a journal that he scratched in during calmer moments at sea. Here is an excerpt describing his vision for a retail store, entered on May 26, 1943,

“Thought of the (retail furnishings salon) shop for gathering together all beautiful and useful modern objects, which could be termed ‘furnishings’... Anonymous discoveries and subcontracted and assembled pieces of my design: foam and webbed couch in church pew form, telescoping coffee tables of magnesium or plastic, ... fabrics ... grass matting to a special design ... restaurant adjacent, movies, bar, a small haven for those interested ... a trip abroad to buy imports first thing after peace.” “In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father.”

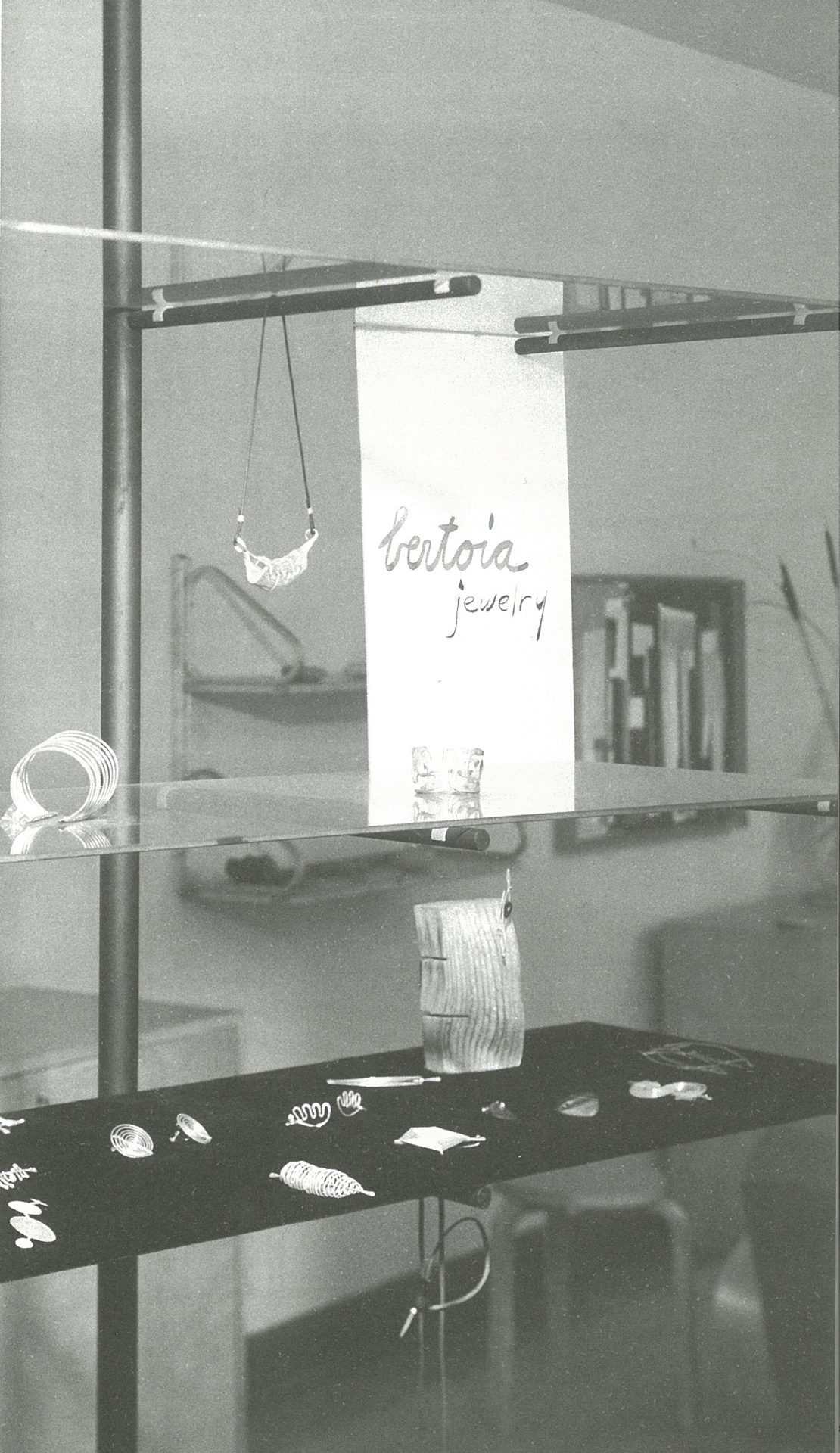

Wasting no time postwar, Dad got permission to handle the Midwestern franchise for Artek furniture from Scandinavia. Ben Baldwin designed fabrics and window displays. Harry Bertoia showed his jewelry, James Prestini sold his turned wooden bowls, artists queued up to exhibit in the space, and Baldwin Kingrey opened its doors to an eager audience hungry for modern design.

In words from John Brunetti, author of Baldwin Kingrey, Midcentury Modern in Chicago, 1947–1957,

“Baldwin Kingrey was more than a retail enterprise. It served as an informal gathering place for students and faculty from Chicago’s influential Institute of Design (ID) as well as the city’s architects and interior designers, who looked for inspiration from the store’s inventory of furniture by leading modernist designers such as Alvar Aalto, Bruno Mathsson, Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen.”

My father started his architectural practice at a drafting table in the back of the Baldwin Kingrey store. He did all the graphics for the store, designed a line of furniture and lighting he called BALDRY, designed open shelving of floating glass and steel poles to display Bertoia jewelry, Venini vases and “Chem Ware”—beakers and Petri dishes in simple, beautiful forms, that they found in the industrial section of the city. There was resourcefulness, an informality, and a frugality at play. In my mother’s words,

“Harry and I stopped at a place that sold Cadillacs on LaSalle Street. They were selling out their leather for automobiles, so we bought the whole batch. A lot of our furniture was covered in Cadillac leather! We were in a sense the precursor to Crate and Barrel. They came down to study us a lot. Carole Segal (founder of Crate and Barrel) was a friend of mine, and I gave her help. I gave her a lot of source material.”

As I was growing up, there was a steady stream of visitors, all immersed in modern design. My mother reminisced,

“You couldn’t travel across the country without changing planes or trains in Chicago. Everyone would stop in Chicago. The people that rushed into Baldwin Kingrey were mostly from the city and they didn’t have much money. Instead, they had some sort of new outlook—a vision. They loved the simplicity of our ‘plain’ furniture.”

The road was unpaved, the waters uncharted, the possibilities endless. Many would visit our house to exchange ideas, talk about projects, drink a cocktail or two, even draw at the dinner table. One of these more salient meetings I remember clearly:

I must have been ten or eleven when a distinguished elderly gentleman came to visit us in Barrington. My father was notably excited to share our modern house with him. When it was time to leave, he escorted him down the walkway under the grape arbor to his car with me trailing behind. As he drove off, my father turned to me with tears streaming and whispered, “There goes my mentor. There goes the most important man in my life.” This was none other than Alvar Aalto, who had been Dad’s professor and was a great influence on his architecture and design philosophy.

First pitstop in Aspen

When peace came in 1945, Dad stepped off his ship in San Francisco and he and Mom drove eastward. On their way back to Chicago, they stopped in Aspen and took some black-and-white photographs of downtown. The town consisted of several stone and brick buildings—the Courthouse, the Wheeler Opera House, the church and Hotel Jerome. All other structures were small Victorians, a few storefronts, dirt roads, and occasional wooden lean-tos that sheltered a few dozing horses. Many of the houses had been plunked on rubble walls to speed construction for miners and their families in the boom of the late 1800s. Builders often used pattern books with a 12/12 pitch for snow load, imparting a human scale that has long since been lost.

Dad—an avid skier—fell in love with Aspen and began a tradition of visiting each winter and summer that lasted throughout his life. Luckily, he included us in this adventure, and, thus, I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as “the town Chicago built.”

“I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as ‘the town Chicago built.’ ”

In the 1940s in Chicago, my parents were friends with Walter Paepcke, a successful industrialist, philanthropist, and president of the Container Corporation of America. It was Walter’s remarkable wife Elizabeth, a notable influence on Chicago’s cultural life and one of Mom’s favorite people, who exposed Walter to modern design and artistic sensibilities. In this spirit, Paepcke consulted with Walter Gropius, brought Laszlo Maholy-Nagy to the Institute of Design, befriended Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer, and photographer Ferenc (Franz) Berko, also at ID at the time. Mom and Dad intersected with ID, as the campus was a hub for young and ambitious modernists.

In a memoir, Elizabeth Paepcke describes her first impression of Aspen after skinning up the mountain in 1939,

“At the top, we halted in frozen admiration. In all that landscape of rock, snow and ice, there was neither print of animal nor track of man. We were alone as though the world had just been created and we its first inhabitants.”

Walter Paepcke first visited Aspen in the spring of 1945 urged by Elizabeth. To him, this seemed the idyllic place to implement a new Chautauqua. The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, “for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.” Thus the Aspen Institute of Humanistic Studies was born. Herbert Bayer was brought in to oversee the design of the campus, and Franz Berko became the Institute’s in-house photographer. The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.

“The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, ‘for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.’ ”

“The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.”

There was a palpable charm to Aspen in the fifties and sixties, which I feel so fortunate to have experienced first hand. Many Europeans returned to the town to settle after serving in the famed 10th Mountain Division during the war. Their training camp, Camp Hale, was nearby and enlisted men would often ski Aspen on the weekends. Friedl Pfeifer was one who started the Aspen Ski School; Fritz Benedict set up an architectural practice. After the war, many of these veterans taught skiing in winter and worked as carpenters in summer. Their wives typically ran the shops, bakeries, and clothing stores in town. Franz Berko stayed, continued his photographic career, and raised his family. His wife Mirte ran a toy shop that sold wooden toys from Europe. Herbert Bayer designed the early buildings at the Aspen Institute and settled in town with his wife Joella. Fritz Benedict, the noted local architect, married Joella’s sister Fabi, and he began developing Aspen. Joella and Fabi shared a famous mother—the poet Mina Loy. This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its “quiet years.” My parents were in the midst of the action.

“This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its ‘quiet years.’ ”

Christmases at the Hotel Jerome

Nora Berko, daughter of Franz and Mirte, remembers visiting us at the Hotel Jerome every Christmas. We always stayed in the southeast corner with full view through the Victorian lace curtains of Main Street and Ajax Mountain. As our collective parents went out to dinner and dancing, usually at the Red Onion, we had full run of the rickety hotel, much like Eloise at the Plaza. With its worn and dusty velvet furniture, Victorian floral wallpaper, and black-and-white photos of skiers sporting the reverse shoulder stance and the latest style of stretch pants, it was a far cry from our modern and minimal environment at home. We ran up and down the creaking stairs and played in the elevator—a novelty—as it was the only one in town. The rooms cost ten dollars per night, radiators clanked, and in some seasons ropes were ceremoniously draped across the room sinks warning of giardia in the water. But we loved the Jerome. It felt like an old comfortable shoe. The Paepckes leased the hotel as well as the Opera House so Elizabeth had license to paint the exterior white with light blue arches over the windows. The hotel looked like a grand Bavarian wedding cake in a perpetual wink; an impressive structure always easy to spot for a youngster finding her way home after ski school. It stayed this way for several decades.

Every Christmas we walked through snowy streets to the Berko’s for Christmas dinner. Their house was a modestly scaled and cozy Victorian in Aspen’s west end. Real candles burned on the Christmas tree, which was festooned with wooden ornaments from Mirte’s toy shop. Marzipan treats imported from Europe were served. There was no central heat. Brrrr. But for a young girl, I was sure that I was encompassed within a magical snow globe.

Aspen became our second home

In the late sixties, my mother bought a small Victorian in Aspen's west end for a mere pittance. We began to spend summers in the mountains, which was a blessed relief from the mugginess of the Midwest. My father worked on projects in and around Aspen. Many went unbuilt but some were realized, including the Given Institute. He had a plan for a new airport, and he wanted to bring light rail from Glenwood to Aspen to alleviate vehicular traffic. Always drawing, usually at the kitchen table, I rarely saw him without a pencil in hand. In 1969 Charles Moore (who taught at Yale), and Fritz Benedict lured a class of Yale architectural grad students to spend a summer in the nearby mountains and build experimental projects. When these young, handsome students appeared, they were eager to rub shoulders with my father at his kitchen table. (A few rubbed shoulders with his daughters as well!) One of these architects, Harry Teague, arrived and never left. Over four decades, he has made a significant imprint on the town, designing notable residences and many of Aspen’s most prestigious cultural buildings, including Harris Hall, the Aspen Music School campus, and the Aspen Center For Physics. He has become one of Aspen’s “own” by championing a humanist aesthetic that continues to raise the bar of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley.

Aspen today

Though old Aspen is rapidly fading, thank goodness there are offspring. I am currently collaborating with Teague on a family compound for Nora Berko and her family that incorporates her father’s studio, now designated historic. Her daughter Mirte has dedicated much time and effort organizing her grandfather’s impressive archives of photographs for us to appreciate into perpetuity. The Aspen Institute carries on robustly while continuing to pay homage to its early founders and players. △

Read "Growing Up Weese" to find out what artist and designer Marcia Weese is up to today.

A-Frames

The right form at the right time

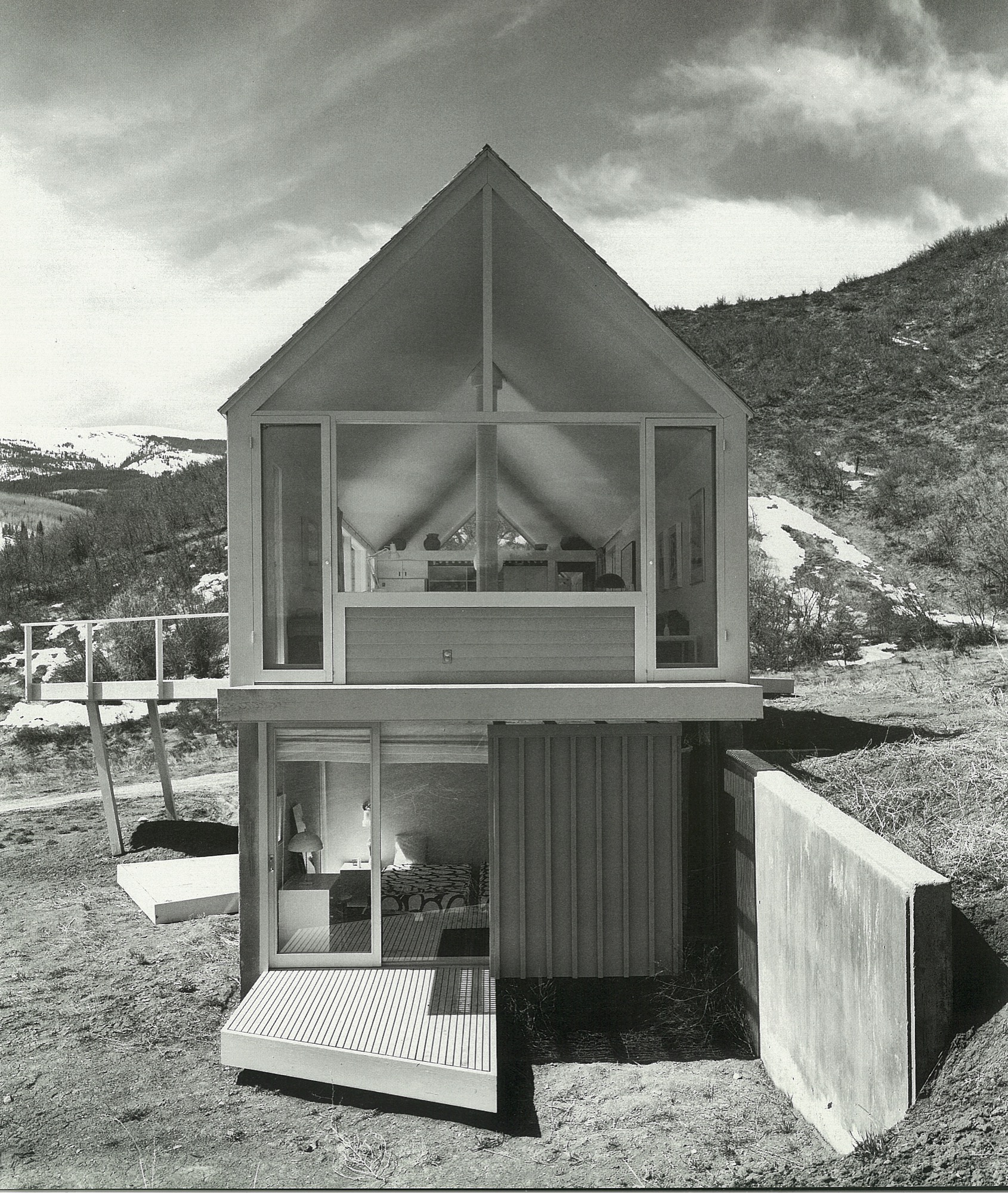

Spawned by postwar affluence, A-frame cabins became the quintessential American vacation home of the 1950s and 60s. A look at what made these icons of middle-class leisure immensely popular then, and what it is like to remodel and live in one today. “The design is intuitive,” says architectural historian Chad Randl, author of the book A-frame (Princeton Architectural Press), about the A-frame’s triangular structure. Why else would different cultures have turned to this universal, unifying building type, independently, throughout time and across the globe?

Was it intuition, too, that told Rudolf Schindler in 1936 to carry the roof down to the ground and fill both gables with glass? The Austrian-born architect needed to find a way to comply with local building codes when he was commissioned a modest vacation home suitable for the mountainside setting above Lake Arrowhead, California. The upshot was an A-frame built twenty years before its time.

By the middle of the twentieth century, architects in postwar America sought a more casual yet visually dramatic design conducive to relaxed seaside and mountain living. The A-frame was both comfortably familiar (pitched roof) and playfully novel. Because these weren’t primary homes, the architects could enjoy more freedom in designing wide-open spaces with fewer partitions and very small bedrooms and bunk rooms.

"The A-frame was both comfortably familiar (pitched roof) and playfully novel."

Genesis: The Leisure House

In 1950, Interiors magazine published an A-frame by San Francisco-based architectural designer John Carden Campbell: the Leisure House. It hit the mark on the era’s modernist style sensibility, down to the butterfly chairs. Campbell was fond of saying the house enclosed the most space in the most dramatic way for the least amount of money.

After a full-sized model of the Leisure House was exhibited at the 1951 San Francisco Arts Festival, Campbell’s phone wouldn’t stop ringing. Fixing its dimensions to the width of a sheet of plywood reduced the cost and simplified construction so vastly, the Leisure House could now become a do-it-yourself project. Campbell deftly developed a precut kit that contained everything needed to assemble the house, from timber to nails and hammer.

After a full-sized model of the Leisure House was exhibited at the 1951 San Francisco Arts Festival, Campbell’s phone wouldn’t stop ringing. Fixing its dimensions to the width of a sheet of plywood reduced the cost and simplified construction so vastly, the Leisure House could now become a do-it-yourself project. Campbell deftly developed a precut kit that contained everything needed to assemble the house, from timber to nails and hammer.

For the next twenty years, photos of Campbell’s own Leisure House he built across from the Golden Gate Bridge in Mill Valley, California, appeared in countless home magazines and architectural books. The Leisure House was promoted as a natural design for the mountains or the beach, for a summer cottage or a ski cabin. The Leisure House manifested a new leisure culture.

A national phenomenon

The mushrooming popularity of A-frames was fueled by postwar prosperity, which brought owning a second home within reach of the middle class. Suddenly, people had more disposable income and more free time. The A-frame embodied an informal weekend and holiday getaway that was innovative and exciting — a recognizable, identifiable symbol of “the good life.”

“It’s interesting how people individually adapted drawings or kits for their own family’s way of living and for their own technical expertise or lack thereof,” says Randl, who now teaches at the Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning. “What I loved about A-frames was that it was such a simple design, a basic triangular form, but you had so many variations of it, and it was still recognizable as an A-frame.”

"The A-frame embodied an informal weekend and holiday getaway that was innovative and exciting — a recognizable, identifiable symbol of 'the good life.' "

The fall of an Americana archetype

While A-frames were touted as efficient in the use of materials in the 1950s and 60s, they were far from energy efficient by today’s standards. The open-floor-plan homes were notoriously difficult to heat — warm air escaped upward, leaving the downstairs chilly and the bedroom loft uncomfortably hot. Many of the early designs were not insulated at all. Thus, keeping A-frames warm became increasingly challenging with the energy crises of the 1970s. “You had that plywood building that became really expensive to heat once oil got expensive,” Randl remarks.

“That’s when it all crashed down,” says the A-frame expert. “The A-frame lost its cultural cache, and people saw it as cliché.”

A-frame Reframe

Today, Randl considers A-frame vacation cabins an “endangered species.” In the right location, however, these period pieces are still sought-after architecture, especially to design enthusiasts with a passion for modernism.

One of those aficionados is Alpine Modern correspondent Paul O’Neil. He bought a 1953 A-frame in Mill Valley across from San Francisco in 2011. The house was designed by Wally Reemelin, an industrial engineer interested in efficient architecture, and is featured in Randl’s book.

O’Neil loved the house at first sight. He liked the way it was situated in the street and on the lot, embracing oak trees. There was more than meets the eye, though. “The house spoke to us,” he recalls about the day he and his partner, Andrew Loesel, discovered the faded treasure during an unplanned stop on a road trip. “There was something special about it. It was asking us to save it. There was a story there,” O’Neil says. “The woman selling it thought we were insane.”

“There was something special about it. It was asking us to save it. There was a story there.”

The Californian has chronicled the history and renovation of the Reemelin A-frame on his blog at aframereframe.com. But before O’Neil could bring the 1,265-square-foot (ca. 118-square-meter) house back to its beauty, he had to undo a poor renovation. An unpermitted addition built in 1964 had left the house with uneven floors and structurally unsafe. By the time O’Neil purchased the house from the third owner, it had been virtually untouched since 1980, with the exception of a new roof from twenty years ago. “We tried to understand what the house originally was like,” he says. “Our goal was to keep the integrity of the house, but make it modern.”

“Our goal was to keep the integrity of the house, but make it modern.”

Once their contractor ripped out the remnants of shoddy remodeling, the house had no structural problems. With elements like a wobbly staircase and an awkwardly placed bathroom gone, O’Neil could rethink the layout. “It was like a puzzle, once we realized what we needed to do.” After updating the electrical and plumbing, and installing insulation, they could focus on designing the house with a nod to its midcentury modern architecture and interior.

Living in San Francisco at the time, O’Neil and Loesel had bought the house for a weekend home, but later decided to live there full time, in the spirit of living smaller and simply. “If a house is well-built, it doesn’t have to be big,” O’Neil says.

“If a house is well built, it doesn’t have to be big.”

In fact, Randl agrees that in the context of the small-house movement and people’s yearning for a simpler, minimal lifestyle, the design concept of the A-frame could once again fit contemporary zeitgeist. “It’s got that reference to the past while also being modest,” the architecture expert says. “That has appeal again.” △