Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Family HQ in Alaska

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner build a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner built a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner built a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

Tens of thousands of years ago, a glacier slid its way through southern Alaska and carved out the Matanuska-Susitna Valley. Bound by three massive mountain ranges and dotted with lakes, it’s an unabashedly wild place. Hundred-pound cabbages flourish in endless summer sunshine, caribou outnumber people, and towering Denali presides over it all. "You can go 1000 miles here without crossing a road," says Martin Buser. "Most people can’t grasp that kind of freedom." A four-time winner of the Iditarod—the grueling dogsled race from Anchorage to Nome—Buser spends his days crisscrossing the landscape with his dogs. So, for his dream home with his wife, Kathy Chapoton, there was no question that the spectacularly rugged setting needed to be the driving force behind the design.

"You can go 1000 miles here without crossing a road. Most people can’t grasp that kind of freedom."

An Alaskan story

The story of how the couple met and found the site is typically Alaskan. Chapoton moved from New Orleans to Anchorage in 1979, at a time when the state government let people claim land for pennies as a way of getting back tax dollars. Soon after relocating, she joined a group of friends one day in early January to stake out the five acres allowed to each person. "It was 50 below zero, my teeth were frozen, I didn’t even know how to read a compass, and I had to walk around and literally mark the parcel," she says. "It was hilarious." Registering her claim at the office in Anchorage, she bumped into Buser, a recent Swiss transplant, and the two married not long after.

The new House for a Musher

For 20 years, the growing family (sons Nicolai and Rohn are named after Iditarod checkpoints) lived in a large house that Buser built on the land, adjacent to the kennel where his hundred-odd dogs reside. In 1996, a wildfire swept through the area: "It was pretty ugly," remembers Chapoton. As a result, people started selling off their nearby plots, and the couple snatched up 25 additional acres—including a mountaintop site that they had been eyeing for years. "It was the primo lot," says Chapoton.

Buser built a little cabin on the top of the mountain as a weekend retreat, but the combination of killer views and the couple finding themselves empty nesters convinced the pair to make that site their permanent home. They moved the cabin by truck to a nearby site (son Rohn lives there now) and called on architects Petra Sattler-Smith and Klaus Mayer of Anchorage firm Mayer Sattler-Smith to design a house. Though Buser had built several homes, the couple knew this site deserved something special. "Because of the multitude of views, we couldn’t take advantage of the site ourselves. We knew our limitations," Chapoton says.

Denali in view

Everything about the 2,450-square-foot house centers on the natural setting. "It was important to have every room look to Denali, which is the ultimate view in Alaska," says Mayer. To do so, the architects created a long, lean, L-shaped house. The blackened, local spruce cladding pays homage to the area’s wildfire, while also mimicking a glacial erratic—a nonnative rock deposited by a moving glacier. The courtyard and part of the kitchen are slightly offset, following the lines of the site’s hilltop topography, while the rest of the house points directly to Denali National Park.

"It was important to have every room look to Denali, which is the ultimate view in Alaska."

Inside

Inside, the walls are paneled in Alaskan yellow cedar, as if the charred exterior has been peeled back to reveal glowing, living wood inside. The public areas lie in one long sight line that starts in the courtyard outside, streams through the living and dining rooms and kitchen, and slips out onto the northern horizon through a wall of sliding glass. The other side of the L contains he bedrooms and bathrooms, each with its own framed outlook on Denali. Windows in the hallway and in the family room face south to let in extra sun during darker winter days. There’s also a rooftop deck, perfect for the family’s many parties—where friends grill mooseburgers and take in the star-filled sky and 360-degree views of the mountains.

Sweat equity

Lest the house seem too fancy for these frontier surroundings, it’s important to remember that Buser built the place himself over six years. Here, there are no construction codes in rural areas ("Building permit?" scoffs Buser. "What’s that?!"), and people prefer sweat equity to bank loans or subcontractors. "When Alaskans say they’re building a house, it means we’re swinging a hammer, digging in the dirt, and trimming it out," says Buser. Yet, this DIY ethos meant that Buser’s solutions were sometimes those of a would-be MacGyver. He and Chapoton charred the cladding using a weed burner and a garden hose; the 800-pound glass doors were lifted into place using Buser’s rigging of dogsled runners, pulleys, and brute strength; and he sliced open two birch trees to make the dining room table.

"When Alaskans say they’re building a house, it means we’re swinging a hammer, digging in the dirt, and trimming it out."

At the end of a typical day, Buser comes home from an 80-mile dogsled ride as the last rays of sun linger on the mountains. Inside, Chapoton (now retired from teaching) whips up a salmon meal for ten, and the gregarious couple shares wine with friends around a crackling fireplace. When everyone’s left, Buser and Chapoton will tuck into their bed, watching the vivid hues of the northern lights dance through the windows. Says Chapoton of her love of the house, "Maybe Einstein said it most simply: ‘Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.’ " △

The Building Friendship

Friends since preschool and sharing a love for design and the mountains, the founders of MTN Lab, an experimental furniture and art studio in Colorado, have always been building things together

Harris Hine and Rudy Unrau have been best friends since preschool. Now both 27 years old, they have founded MTN Lab, an experimental furniture and art studio in Colorado. Growing up in Boulder, Colorado, the lifelong friends have been building things together since they can remember—skis, bikes, random projects. But it wasn’t until spring 2015 that the idea for MTN Lab was born. Both back in Boulder, Hine and Unrau began showing sculptures at Studio Como in Denver’s RiNo art district at the time. “Getting in there is what really materialized the company,” Unrau recalls. “That’s when we came up with our name and went from just building stuff to actually focusing on a business.”

The two men, both quiet and reflective, share an ardent love for design and the mountains. Yet, they come together at MTN Lab—at the intersection of art and adventure—from opposite directions: Hine a trained designer and woodworker, Unrau a former professional mountain biker turned woodsman fighting wildfires for the Forest Service.

Harris Hine

Harris Hine grew up profoundly influenced by his father, Vienna-born modernist architect Harvey Hine, who founded HMH Architecture + Interiors in Boulder.

“I’ve always been torn between the design side of my personality and just wanting to be in the woods,” Hine shares. He went to school for design at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn before moving from New York City to Portland, Oregon, where he worked as industrial designer. “I didn’t find any fulfillment doing other people’s projects, and I didn’t really like the mass production side of product design,” he admits.

All those years, Hine pined for the woods, where his old friend was.

Rudy Unrau

Unrau, while attending college in Western Colorado, signed on with the United States Forest Service. “I was on track to becoming a smoke jumper, working for a helicopter crew down in Durango,” the long and lanky woodworker recounts. “It was a great setup because you work a ton in the summer, and then you get winter free to do whatever you want, like ski and move to Canada.”

Throughout those years, Unrau had been harboring the desire to return to making art. “Seeing the things you see when you get to fly around and travel the US and go to all of the mountain ranges... I had ideas emerge to work with the trees that had been burnt or partially burnt in fires because they get so twisted and cool.”

"I had ideas emerge to work with the trees that had been burnt or partially burnt in fires because they get so twisted and cool.”

Joint adventure up north

At last, one pivotal winter Hine and Unrau moved to British Columbia together to ski. Their close friendship and mutual influence would impact each man’s path. “Rudy was all in the woods,” Hine remembers, “Living together pulled him back into the design world and brought me back into the woods.”

Unrau agrees: “I’ve always been at home in the woods. Growing up, I really wanted to pursue mountain biking, so I raced mountain bikes professionally for quite a few years.” After the athlete got “a little bit tired” of mountain bike racing in world cups, he focused on skiing.

Skiing in Canada was good fun. Winter gone, however, Unrau planned to work another fire season. The outdoorsman envisioned himself carrying on that seasonal rhythm of demanding service and wild adventures in the snow for years until he had and his friend had their fill of youth and independence. “And... I crashed paragliding,” he tells, falling solemn all of a sudden. “I broke my back and almost died and spent half a year recovering.”

His loyal friend by his side, Unrau needed to reevaluate his future. “I realized, I wouldn’t be able to do fire again,” he says. “And then it was pretty natural the way MTN Lab came together—us getting our shop set up to where we could build.”

The MTN Lab process

Starting with sculptures, the duo soon began venturing into furniture. Their vision is to grow the Conifer studio into an art collective, with more creatives joining them. They are even planning to build a tiny house to accommodate visiting artists and designers.

MTN Lab is as much a concept as it is a company. “Our process is the most indicative of what we make,” Hine explains. The founders source all of their materials themselves in the Colorado mountains. “We quarry our own stones to carve and collect our own wood.” Like it was for generations of makers in the mountains before them, MTN Lab’s workflow follows nature’s rhythmic swing. “Right now it’s the season for us to go get river stones because the flow just came down,” Hine tells me, when I sit down with him and his partner on that warm day in early September. “And we are doing antler stuff because we found a bunch of Elk sheds. That’s this flow that we follow.” Adds Unrau: “Our company is trying to do the whole process from sourcing, getting our materials, designing it, building it ourselves, photographing it ourselves.”

The friend believes having grown up in the mountains is what motivates them to see the entire process through, from beginning to end. “Spending all of your free time in the backcountry—you’re just so inspired by what you’re surrounded by,” Unrau says. “Initially, we were out there to ski, climbing to ski. We were dirt-biking. But when you spend that much time out there, it altered our perception of why we were there. And now it’s awesome because we get to ski, but that’s not the whole part of the process. The ski is the vessel for finding the materials—as well as the inspiration.”

“The ski is the vessel for finding the materials—as well as the inspiration.”

Connecting nature and art

“I’ve always liked minimalist design, and I rarely see that done with natural materials,” Hine says. “You look at Bauhaus stuff, and it’s very industrialized. My dad being the modernist he is, half of me is always striving for that simplicity. But then there is the other part of me... the Colorado guy. And I see these cool pieces of wood and antlers and it naturally merged. In college, I was more on the industrial, clean-cut metal side of things, and my style has evolved more and more into a hybrid of rustic and modern.”

Unrau, for his part, never earned an art or design degree, nor does the lack of academic study in the field limit him in his current work. “We really do our designing when we’re out in the woods. We don’t sit down in an office to draw. We see the material, and the material almost dictates its design.”

They usually know right away, if a piece of wood they come upon in the forest will transform into an art sculpture, a table, or something else entirely. Back at the studio, they combine found pieces of wood or elk shed with marble and often with contrasting metal. The final artwork or furniture piece comes together like a collage. While the sculptures are never drawn out, the furniture generally is. “We design our table bases, draw them by hand. Sometimes, we bring it into CAD.”

The day I met up with Unrau and Hine, they had come down from their studio above 8000 feet to deliver a piece of art they made for the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. “We had this mobile,” Hine begins, chuckling, “And then Rudy dropped it on the staircase, and we were like ‘Oh, no, we’re so crushed. And we had to quickly build it a second time yesterday, and it came out eight times better than the first. That process isn’t always easy to rely on, but sometimes when you make it again, it’s better. This is how we continuously design.”

Speaking about the synergy between Colorado’s magnificent nature, rich history and tradition, and progressive modern art, Hine notes that he is profoundly influenced by the stone carvings of American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. “It’s that blend of leaving these big natural boulders and polishing one face of it.”

Rustic designs with wood and stone are ubiquitous. “But it’s hard to find someone who has done them simple enough so that these materials individually speak for themselves,” hine says. “Antler furniture is really something we have been experimenting with, because it’s hard to find a simple antler-anything. All the chandeliers are the same hunter antler cluster. And all of a sudden, you are appreciating the simplicity of the singular antler as a sculptural element. That’s what makes it alpine modern, and not just alpine.”

“And all of a sudden, you are appreciating the simplicity of the singular antler as a sculptural element. That’s what makes it alpine modern, and not just alpine.”

A modernists at heart, Hine still looks to the arts and crafts movement for inspiration. “Not stylistically but the whole concept of it is huge, especially since my education is in mass production and industrial design and product development. And going back to actually hand-building one-off pieces from the found materials we use, you can’t really build the same piece twice. It’s almost like we’re in an arts and crafts revival, which is weird for me because that’s the antithesis of the Bauhaus influence, of going from craft to industrial production.”

Our conversation later on reveals that the two 27 year olds are somewhat of an antithesis, too—to their fellow millennials. The Internet, they admit tittering, is their shortcoming. “Neither of us really enjoys social media, self promotion, or even doing the sales part,” Hine says. “It’s the cliché artist who doesn’t sell his stuff. We just are either in the woods or in the shop. It never feels like were working.”

MTN Lab projects

Each MTN Lab piece embodies a story of adventure and friendship.

For example, Unrau says seventy years ago, many trees were cut down to make room for high-voltage lines to Fairplay, south of Breckenridge, Colorado. “The company just left them, so these big old-growth rounds have been drying up there all these years,” he says. MTN Lab milled the pine rounds into table tops. “That’s our next big design push, designing bases for those tables,” he says. “Or the motorcycle, which is a lifelong dream we’ve shared since we were little kids.”

Indeed, Hine and Unrau want to build a motorcycle entirely from scratch, the back end made hand-carved in wood. Before winter, they even want to experiment with producing their our own steel, from mining the rock to crushing and melting it. Whether the resulting material will in fact be usable won’t matter as much: “At least we will be able to appreciate the process when we go to the store and buy steel.”

“The motorcycle is going to be very much like our furniture and our sculptures,” Unrau says. “I would describe it as an art bike. It’s going to be functional. It’s going to ride very well, but it’s not going to look like a conventional motorcycle. I don’t know if we’re going to be willing to sell it.” The business partners are also debating whether they will ever have the heart to sell the 1960s Airstream that once belonged to Unrau’s grandfather and they just finished restoring. “I never want to sell any of our stuff,” Unrau admits, laughing. “It’s hopeless.” △

The Adventure House

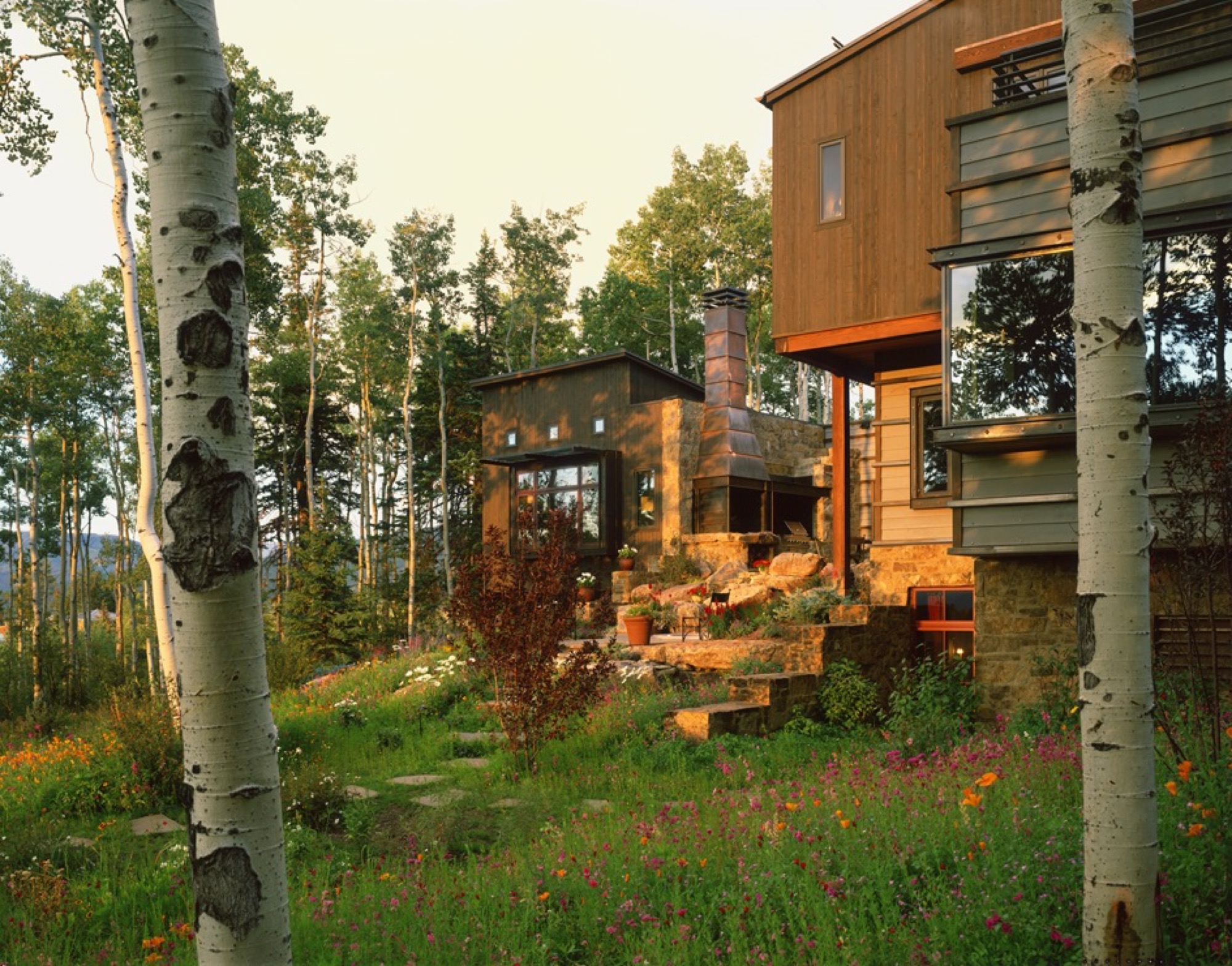

Seattle’s Olson Kundig creates an extraordinary family outpost with views of the North Cascades

Like wagons circling a campfire, a home that consists of sleek, airy pavilions embodies the concept of gathering.

When it comes to second homes, adventure makes the heart grow fonder. At least that’s the premise—and the promise—upon which Tom Kundig, of Seattle-based Olson Kundig, based his design for the staggeringly beautiful Studhorse residence in Washington’s remote Methow Valley. “Second homes are about adventure, and they are the homes that leave the most indelible memories,” Kundig says. “The best way to do that is to make them unconventional.” And that’s when things get interesting. Because when an architect of Kundig’s caliber decides to steer design in an unconventional direction, all manner of daring surprises can occur.

These days, Tom Kundig is a much-heralded, multi-award-winning architect (fifty and counting from the American Institute of Architects alone) engaged in projects spanning the globe. Yet, despite his growing international artistic stature, Kundig’s inspiration remains rooted in the profound experiences of his mountain-climbing youth. “I can tell you from experience that while mountain climbing may seem romantic, it’s also uncomfortable and scary,” he confesses. “You’re cold, hot, and sore. Why would anyone do it, if they thought about it logically? But it’s about engaging life vigorously. So is all of my best work.”

“While mountain climbing may seem romantic, it’s also uncomfortable and scary. You’re cold, hot, and sore. Why would anyone do it, if they thought about it logically? But it’s about engaging life vigorously. So is all of my best work.”

One fearless family

Fortunately, the clients who invited Kundig to design a mountain getaway for their young family on the edge of the North Cascades a few hours north-east of Seattle had a bold spirit and zest for adventure themselves. In fact, sharing adventures was part of their deliberate and mindful approach to building family memories. So it made sense that a rural retreat from their city routines would provide plenty of opportunity for outside-the-box living.

Truly life-enriching adventures are awakened by extraordinary locations, and this home’s setting is spectacular—twenty sagebrush-and-wildflower-strewn acres of rolling terrain unfurling beside Studhorse Ridge and overlooking the towering North Cascades and a lush stretch of the Methow Valley and Pearrygin Lake. It’s a quiet and peaceful perch with 360-degree views of wild Washington beauty.

Not surprisingly, the homeowners intended to spend as much time as possible outdoors, and that suited Kundig just fine. “Many of my buildings, even the public ones, involve being exposed to the elements in some way,” he notes. “And sometimes, there is even an element of risk, or daring, which is desired on the client’s part and intentional on my part.” So this home was designed expressly to provide plenty of access to fresh-air freedom. “The clients wanted a central space where the family and guests could come together in the landscape,” Kundig recalls. “We came up with the concept of the house feeling like a vintage motel with a series of buildings around a courtyard. From there, the conversation evolved into the idea of exploring the tradition of circling wagons around a campfire.” This engaging idea became the seed from which the entire home grew.

One big boulder

But first they had to deal with a rather large rock. “The site was actually completely empty when we began,” Kundig explains. “Except for the boulder that was positioned in what is now the courtyard area. It is a glacial erratic—a rock that a glacier drops as it recedes—and it was a driving element of the house composition, becoming the center point for the project.” So, in a gesture both timeless and eloquent, the home’s structural elements—and, by extension, the family’s activities—congregate around a literal and figurative touchstone. “I envisioned it as a large piece of furniture,” Kundig admits. Whatever you care to call it, the rock has become a much-loved feature of the home. “We loan the house to friends a lot, and we leave a Polaroid camera next to the guestbook,” says the homeowner. “That book probably has a hundred pictures taped inside by now, and I bet ninety of them show people on the rock. People see it and they say, ‘That’s amazing you put this rock here,’ but we say no, we built the house around the rock!”

An elegant assemblage

The home comprises a series of buildings clustered around a central courtyard. Viewed collectively from a distance, the constellation of structures has the striking presence of sculpture artfully arranged in a landscape, but each element is also simply practical. Each structure/pavilion has a defined purpose, and taken together they fulfill all of the family’s requirements, so residents and guests circulate among and between the buildings in daily paths dictated by their activities. The main structure is nearly entirely encased in glass. (Kundig calls it “lantern-like.”) Anchored by a massive concrete fireplace on one end, with a living room, dining area, kitchen, pantry, bar and bath—this is the main indoor gathering space. Another structure just beside it contains private family bedrooms upstairs and a guest bedroom and shared den below. Across the courtyard, a third structure offers space for the garage, storage and laundry facilities, and connects through a breezeway to an extra guest suite. The fourth and smallest building, set slightly apart and in a meadow, houses the sauna.

The structures were meticulously positioned to precisely frame gorgeous mountain and valley views, and the negative space (the open space between buildings) they create was considered with the utmost care. When vistas are framed from different angles, we perceive them in new ways, Project Manager Mark Olthoff explains, and this home’s design repeatedly plays with the idea of varying points of view. Olthoff notes that the moment of arrival is a particularly significant experience, so in this case it was important that the view greeting one’s eyes upon entering the complex from the parking area be pristine. Dazzling glimpses of landscape are framed cleanly by the built structures, with no overlapping edges of rooflines to mar the dramatic impact of the first impression.

Kundig explains that the strategic arrangement of the structures, which he refers to as “lean, geometric pavilions of steel, barn wood and glass,” also puts their extended rooflines to work—providing shade and natural cooling in the heat of summer and creating a covered passageway when rain and snow fall. The central courtyard, swimming and play zone become a natural focal point at the heart of the cluster of buildings, practical for a busy family with energetic children, ideal for entertaining a group of guests, and perfectly charming as an impromptu dance floor.

Simple and solid

Yet, while the home is certainly gracious, it is far from grand. “We relied on everyday building materials when possible and used the common materials in uncommon ways, such as exposed plywood for flooring or walls,” Kundig explains. “The materials—mostly steel, glass, concrete and reclaimed wood—were chosen for their resilience against the scorching summer sun and freezing, windy winters that define the region. The materials are expected to weather over time with their surroundings, and to blend in.” If the wood siding shows quirks of character and age, then that’s because it was salvaged from an old barn in Spokane, Washington. And plywood is more practical than precious. “The ceilings are ACX plywood,” Kundig says. “The rest (cabinets, floor, and walls) is AB marine-grade plywood, which we used because the edges would be exposed and marine grade has tighter laminations and holds an edge better.” With a gray-toned stain, the humble boards take on a refined appearance belying their usual orange-tinged reputation. For her part, the homeowner is delighted with the home’s unfussy durability and general livability. “It’s made to stand up to the occupants,” she says admiringly, noting that the family retreat is “worked hard.”

“We relied on everyday building materials when possible and used the common materials in uncommon ways.”

Four-season comfort is assured, thanks to a series of astute climate considerations. A geothermal heating system (with electrical backup) warms the home and its concrete floors. Air conditioning is unnecessary, given the home’s elevated location, which allows breezes to filter through the rooms. And giant, industrial-sized fans in the living room and bedrooms keep the air circulating. Moreover, many of the walls and windows were designed not merely to open but to essentially disappear, blurring interior-exterior boundaries as the home and its landscape intermingle.

Kinetic elements

And here’s where some of the home’s adventurous personality really comes out to play. Kundig has developed a reputation for buildings that incorporate kinetic elements (Olson Kundig even boasts an in-house “gizmologist”), and this house is no exception. Moving parts are built into the fabric of the home, adding a functional—and undeniably fun—versatility to the spaces. The main pavilion’s floor-to-ceiling windows and giant Fleetwood sliding doors enable the expansive room to completely open to the great outdoors. Nearby, the indoor bar converts to an al fresco watering hole when the steel-and-wood back wall flips open on hydraulic pistons. (Kundig likens the experience to Coney Island.) And in a bravura demonstration of crowd-pleasing cleverness, one entire reclaimed-wood-clad den wall is designed to swivel ninety degrees outwards, so that the big-screen television becomes an outdoor movie screen, and the courtyard—and a perfectly placed semi-circle of landscaped rock seating—becomes an open-air cinema.

[video width="640" height="360" mp4="http://www.alpinemodern.com/editorial/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/400983501.mp4" loop="true" autoplay="true"][/video]

Scandinavian style meets the mountain West

Debbie Kennedy, an interior designer with Olson Kundig, helped guide the creation and selection of furnishings and finishes for the home. “We wanted to stick to a very simple unpretentious palette of materials—materials that feel like they belong in the landscape and the interior,” she says. “Limiting the number of materials helps the spaces flow into one another.” Concrete, steel and reclaimed wood are major players both indoors and outdoors. “The clients are very drawn to Scandinavian design—both contemporary and vintage,” Kennedy explains. “In this instance, the goal was also to incorporate modern refined Western mountain references.” Kundig notes, “The focus was on beautiful yet practical pieces that would age as well as the buildings and, similarly, relate to the region and mountain landscape.”

The homeowners preferred a casual look and a welcoming feel, with occasional bright splashes. “The dining chairs presented a great opportunity to introduce a pop of color,” Kennedy notes. “And the client fell in love with a vintage-blanket chair by Maresa Patterson, so we asked her to work with us on a pair of chairs.” Kundig adds, “A few key pieces—such as the dining table, coffee table, fireplace screen, and built-in beds—were custom-designed by the team.” Kennedy singles out one example: “The folded steel console is from the Tom Kundig Collection and feels like it was ‘meant’ for the house.”

Defying easy categorization, the Studhorse residence is emphatically individual and entirely unforgettable. Perched on a prospect overlooking a breathtaking panorama, the clustered elements of the home manage to both embrace and enhance its incredible surroundings. As a hummingbird flits straight through the open walls of the living room and into the kitchen on a sunny spring afternoon, the allure of Tom Kundig’s vision is clear and complete. As he explains, “Architecture allowed me to have a foot in both places—the technical realm and the poetic realm—and in that magical intersection between the two.” △

“Architecture allowed me to have a foot in both places—the technical realm and the poetic realm—and in that magical intersection between the two.”

The Fragrance of "Out There"

A harvest walk on the wild side with the wilderness perfume crafters of Juniper Ridge

Hall Newbegin is out there. Upon first meeting him, I didn’t expect it. He seemed jovial, unintimidating, and mild-mannered. But in the first five minutes of our conversation he used the phrase “out there” eight times — “Part of what I wanted to do was to just be ‘out there’ . . . Being ‘out there’ just centered me . . . Being ‘out there’ saved me as person . . . I had no idea where this was going, but I loved being ‘out there.’ ”

Return to the wilderness

All of us go through periods of discovery in our lives when we are searching for direction, trying to find out what defines us and how it can drive our life and work. For Newbegin, the founder and head perfumer for Bay Area-based Juniper Ridge, that discovery came after a stint on the East Coast and a return to his roots in the West, a return to the wilderness — “out there” — where he feels most comfortable and alive.

Newbegin never imagined that being “out there” would lead to a burgeoning fragrance business, with his products sold in outlets around the globe. He stumbled upon the idea after trial and error — in his life, in his passions, and in his own business.

Capturing the essence of being “out there” is the driving force for the people who run Juniper Ridge, which proclaims itself the world’s only wilderness fragrance company. Headed by Newbegin and the firm’s chief storyteller and packaging designer, Obi Kaufmann, Juniper Ridge, per its website, is “built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

“Built on the simple idea that nothing smells better than the forest.”

Newbegin and his team embrace this mantra through a process called wild harvesting, where they make real fragrances from the places they know and love — the trails of the rugged and diverse American West.

Their teams of hikers crawl through mountain meadows, smelling the earth, the wild flowers in bloom, or the moss covering the trees, then harvest the ingredients to capture the real scent of that land. Armed with public permits or private permissions, they gather wild flowers, plants, bark, moss, mushrooms, and tree trimmings, then distill and extract fragrance by employing ancient perfume-making techniques of distillation, tincturing, infusion, and enfleurage. These formulations vary yearly and by harvest, due to rainfall, temperature, specific location, and season.

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive.”

“I want people to stick their faces in the ground and just get really primitive,” says Newbegin, whose Instagram handle is @crawlonwetdirt. Yet this call to the primitive is based in fact: Our sense of smell is often called the oldest sense, the only one with a direct connection to the brain. That connection brings pleasure and sparks memory, transporting us in time and place. For the team at Juniper Ridge, the time and place is marked on every bottle of fragrance they sell. In fact, they authenticate the process of each harvest by stamping each package with a harvest number and by documenting the process through an accompanying story and photographs on the Juniper Ridge website.

“Our muse is the place. And our job is to funnel that the best we can,” says Newbegin, pointing to a small spray bottle of Sierra Granite, a fragrance connected to California’s Sierra Nevada. “Everything in this bottle is real. Our test is always ‘Is it the real place?’ ” Some of the other places they have captured include Big Sur (California coast), Siskiyou (Oregon coast), Mojave (Mojave Desert), and Cascade Glacier (Oregon’s Mount Hood).

“Our muse is the place."

Real fragrance resonates

Kaufman notes that as the business has grown, sales have been strongest in Scandinavia and New York City. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, it takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us,” he says. “Ninety-nine percent of the people who buy this have never been to the Mojave Desert, but because it’s real fragrance, it resonates — this is real, it’s not Comme des Garçons, it’s not that bullshit stuff at the Nordstrom’s counter that’s made from petroleum, and that never existed on earth until ten seconds ago. Because this is real, it goes deep into our genetic past — we’re responding to something real.”

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve never been to the Sierra mountains or to Big Sur, [the fragrance] takes you to a place inside your own head that is common to all of us.”

Saved by the wild

While hiking on Marin County’s Mount Tamalpais with the sometimes loquacious but unassuming Newbegin in his worn T-shirt and jeans, it’s hard to imagine that he would describe the transcendent moment of his life as a cliché. But those are the exact words he uses when he muses on the importance of the wilderness and the outdoors: “I feel like it saved my life.”

Growing up in Oregon, with Mount Hood in his backyard, Newbegin spent most of his youth hiking and backpacking. He attended college in New York but knew there was something growing inside of him, “a hunger to get back to the West and be in the mountains . . . I had camping and being outdoors in my blood. It’s a deep West Coast/western cultural thing,” he says.

With a last name like Newbegin, it seemed inevitable that he would eventually find his true calling. That happened in Berkeley, California, after a period he deems his “hippy schooling.” He took inspiration from eco-wilderness writers including Gary Snyder, John Muir, and David Brower and studied under commercial mushroom harvesters, members of native plant societies, and herbal medicine teachers.

New beginning

The real turning point came as he was foraging native medicinal plants in the Sierra Nevada. “I dug my trowel into osha root, and the air just exploded with that smell and it’s like, ‘ahhh.’ It would just slay me,” he says. “I didn’t know what the stuff was. I wasn’t thinking about fragrance or anything. I just loved being out there. It just centered me. It brought me into this world where the big thing is there, and it just brought peace over me. You’re looking at plants, at trees, your map, and you smell the ground and suddenly it breaks. You’re just there. All that chatting in your brain just stops, and you’re just there.”

This was the beginning of an epiphany, but the path from being an outdoorsman to becoming a true perfumer has been sixteen years in the making. “You know how journeys are,” Newbegin says, “You just start taking your steps, and soon you start getting somewhere. And so, I started learning how to extract goo out of plants. I was going to the Berkeley Public Library and trying to figure out the old extraction techniques of how you get the goo out of the plants.”

Eventually, he was mixing that goo with other ingredients to make soap and selling it for four bucks a bar at the Berkeley Farmers’ Market. He describes encounters with his first customers: “They would say, ‘Oh my God, this is Big Sur in a soap.’ ” Sounding a bit like Hemingway, he would give them the authentic story of the day that it was harvested — “I got black sage goo on my arms, and I took a nap under this big black sage shrub and had dreams about it and woke up, and the sun was on my face, and the air was just filled with the cleanness of black sage and bees in the air.” Their response, according to Newbegin: “OK, I’ll take ten of those, right now.”

Goo business

After quickly selling out of his product, Newbegin also realized that he was vastly underpricing his offerings. Over the years, he and his team have refined not only the process to get very consistent quality, they have also learned how to price their product to create a sustainable business. Newbegin laughs when he says, “We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.” And yet, it is a business that is working — with retailers such as Barneys New York now carrying the product, and outlets as far away as Paris, Moscow, and Tokyo.

“We make perfume for people who hate perfume. It’s the worst business model ever.”

And Newbegin’s enthusiasm for his product and the process is still very evident. “When I hand this to someone, I think to myself, ‘Oh, my God, you’re getting something just unbelievable.’ All that green in there . . . This is what Mount Hood was like as of September fourth of last year. All that green goo, tree pitch. It’s just real. It’s just 100 percent real.”

The Juniper Ridge team talks about how this realness is a stark contrast to the more synthetic nature of traditional perfumes. Those classic perfume houses employ someone who is called “a nose” to help them create unique fragrances. Globally, there are around fifty “noses” who are highly sought after for their olfactory abilities.

Although this is rarefied air that Newbegin wants no part of, he does refer to himself as “the Pied Piper of the nose.” He is quick to recall the power of the sense of smell. “My message is, use this primitive thing because it will change the person you are.” The scent of nature “is everywhere, all the time. So wake up your sense of smell,” he exhorts. “I want people to do it, not because they should, but because it’s the most sensually gratifying thing they can experience. It’s wonderful.”

Try for yourself

Newbegin’s final piece of advice: “Do what we do — get outdoors, crawl around on your hands and knees, smell the wet earth beneath your feet. Or if you’re worried about embarrassing yourself (which you should be since people don’t normally crawl around on trails), just start by crushing tree needles and plants under your nose. Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.” △

"Stay with it, keep breathing it in. You may notice yourself feeling things, feeling something about the quietness of the place. That's the power of real fragrance.”

Concrete Perspectives

Australian photographer Jake Weisz discovers the minimalist Amangiri Resort in Southern Utah

Through his lense and all his senses, Australian photographer Jake Weisz (@jakeling) experiences the calm luxe and the raw surrounding nature of Southern Utah’s Amangiri Resort, where minimalist architecture in monochromatic concrete lies below the buttes and mesas of Canyon Point.

After an unforgettable, slow drive along a private, paved road between colossal ridges and across vast landscapes, we arrived at what I can only describe as a concrete castle hiding in the rocks of Southern Utah. Amangiri was and remains the greatest architectural experience of my life as a photographer. Minimalism, texture, silhouette... all unassuming until I wandered through this artistic haven of concrete walls.

A collaborative design by architects Rick Joy (Tucson, Arizona), Marwan Al-Sayed (Hollywood, California) and Wendell Burnette (Phoenix, Arizona), Amangiri spreads over 600 acres (243 hectares), with 34 suites and a four-bedroom mesa home, a lounge, several swimming pools, spa, fitness center and a central pavilion that includes a library, art gallery, and both private and public dining areas. The architects were commissioned by legendary hotelier Adrian Zecha, whose Aman Resorts have redefined luxury travel in epic proportions.

Arriving at the resort

We wandered across the dramatic entrance, past the protruding canyon on the right and stepped into the first breezeway, one of numerous voluminous concrete corridors that connect each pavilion to the next, framing the valleys in the distance and creating different moments of awe every time you step inside. Throughout the day, the sun hits each breezeway at different angles, giving light and shadow new meaning, in a continuous cycle from dawn until dusk. Impressions of grandeur aside, with each stride deeper into these grand hallways, I felt closer to sublime serenity; this indescribable feeling of peace.

We were shown to our room, a one-bedroom suite on the edge of the property, backing to what at first glance reminded me of a set built for a spaghetti Western: rolling tumbleweeds, the squeaks of desert mice, expeditious hares scurrying about, the scene set against luminous canyons and a distant view of Broken Arrow Cave, an indigenous, spiritual sanctuary. Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.

“Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.”

Exploring perspectives

After some rest in our noble lodgings, the photographer in me yearned to roam the grounds, Canon in hand, and to capture the tranquil austerity surrounding us. Being here, each of the architects’ decisions made sense. Moments of monotony broken by jagged slices of deep, sweeping pastel views. The polished concrete’s organic texture caressed by soft waterfalls cascading down the walls. Brief Edenic allusions in fruitful apple trees, ripe for the picking. To grasp we were only a couple hours’ drive from Las Vegas, Nevada, was almost impossible.

Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls. Rather than being clinical or cold, as unknowing observers might reckon from afar, the stark concrete structure’s monochromatic elegance creates harmonious balance between the arid landscape in a desolate summer climate and shadowed walkways affording gentle breezes of desert wind.

“Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls.”

Fortress of luxe

Stepping inside Amangiri superseded any notions I had of comfort and luxe. The main pavilion is a multipurpose common area scented by burning fresh sage and sunburned grain. On the walls, copious Ulrike Arnold artworks implement abstraction from the concrete’s silky texture. The interior seamlessly merges textures as if designed by rhythmic dictation. Soft leathers and animal hides, smooth oak and cement surfaces all amalgamate with the rough, rambling terrain that surrounds the resort.

I experienced color in this place like never before—the perfectly blended gradient changes from earth tones to milky hues. The architects of Amangiri also designed all interior features; furnishings, lighting, signage… all the elements reflect the Southwestern landscape and culture with subtle, emblematic references to the Native American tribes that once inhabited Canyon Point.

Dining at dusk

The Amangiri invited us to take our first meal alfresco in the Desert Lounge, a rather humbling setting for our dinner at dusk. Sitting across from my friend, charging our glasses of wine and looking out at the immense horizon, overcome with divine silence and calm, we couldn’t speak but simply look and listen. Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food. Amangiri presents a rather auspicious combination of locally sourced, farm-fresh produce and materials with modern interpretations of Southwestern traditions. Plate for plate, the decadent courses filled us, until we turned in for the night. First day, well spent.

“Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food.”

An early adventure

From the crack of dawn, Amangiri had been already awake and buzzing. We were informed to wear shoes suitable for an adventure and were later met by a car. Amangiri sits among some of the continent’s most grandiose, well-protected natural phenomena, and we were booked to experience one the resort is very proud to have on its land. At the foot of the largest of the canyons, they put us in climbing harnesses before we set off on a Via Ferrata, Italian for “Iron road.” This modern style of climbing journey involved steel cables and staples already in place for a more protected climb. The concept is to give inexperienced climbers the ability to enjoy rather dramatic and difficult peaks. And now, with my feet firmly back on the ground, I can say, the peak was indeed spectacular. Nerves aside, climbing to the top allowed me to truly experience the vastness of this beautiful place and the fragility of this natural ecosystem. I do, however, recommend taking an extra few breaths before crossing Amangiri’s signature suspension bridge between two peaks. Walking across with my camera was a rather nerve-racking experience.

After that intense climb and exploring more of the resort’s outdoor adventures, the best decision was to spend our afternoon at the Amangiri Spa. The minimalist design of this serene adults-only oasis manifested the very concepts of relief. Instead of receiving a massage treatment, I spent most of my time self-reflecting in the floating cave’s Persian salt pool. 30 minutes of pure and simple bliss, resting on the surface of tepid water, scored by meditation melodies has become my new idea of elegant content.

Departing to return

Our departure was suitingly emblematic of our entire experience at Amangiri. As we unhurriedly drove past the minimalist concrete marvel, through the resort’s expansive acreage and past a private plane landing nearby, I began to appreciate the sheer magnitude of my weeklong stay here. The space has inspired a newfound understanding of lines and light, and a greater comprehension of the relationship between nature and man-made creations. As I left, I already longed to return. △

Utahan Utopia

Summit Powder Mountain in Utah is a visionary colony of cabins designed by emerging Slovenian architect Srđan Nađ

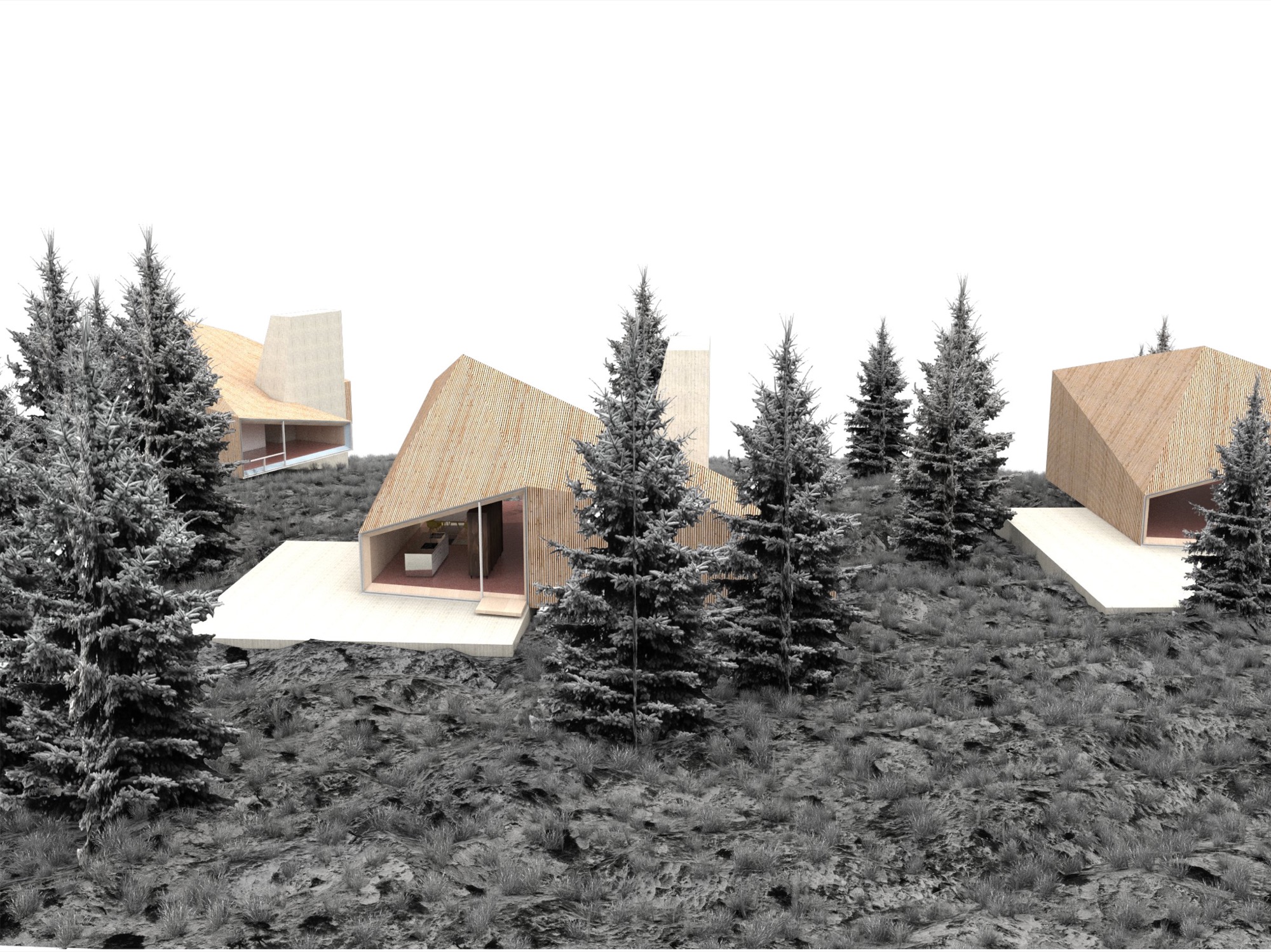

A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the conversation on nature-respecting modern mountain architecture and communal living on Powder Mountain, where an enigmatic group of entrepreneurs, creatives, and altruists is building a pioneering alpine village. “We bought a mountain.”

So begins the backstory of Summit Powder Mountain, a visionary colony of cabins and an alpine village being dreamed up in Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

Elliott Bisnow and the Summit Series

Behind the idea is Summit, an event business started by Elliott Bisnow, a founding board member of the United Nations Foundation’s Global Entrepreneurs Council. What began as a small gathering of a few dozen investors, business whiz kids, and creatives over a short few years grew into the Summit Series: traveling invitational events that summon hundreds of thought leaders and different-thinkers from around the world. "What would it look like if Davos and Burning Man had a baby?" The Guardian rhetorically wondered in a recent article about the Summit Series. For its latest flagship event, Summit at Sea, 2,500 chosen attendees boarded a cruise ship in Miami for a four-day conference in international waters.

Rooting down in Utah

Now Summit is building a permanent base camp for its forums—a high-alpine town for its growing tribe to come home to. Summit purchased Powder Mountain, including the ski resort that has been operating there since the 1970s, with the vision to fundamentally reimagine and experiment with how people live together, shelter themselves, and converge for the greater good. “I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world,” says Summit design director Sam Arthur, who moved to Utah to see the project through. Since buying the mountain in 2013, Summit has called on sundry architecture and design gurus, even sacred geometry to conceive this test bed for communal living. But the group still needed a cohesive cabin concept, a trademark design that considers the demands of living at 8,400 feet (2,560 meters) altitude, of building sensibly on historically mostly undeveloped, pristine mountain land that includes an elk reserve, natural waterways, and thriving wildlife. A sheep ranch was the only settlement on the mountain for the longest time.

“I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world.”

Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition

Thus, Summit’s Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition challenged the global guild of architects, engineers, artists—masters and students alike—to design sustainable cabins that embody the leadership’s ideals of sustainability, use of natural materials, and humble expression. The winning concept would guide the architectural ethos for more than 500 single-family homes, limited to 2,500 square feet (232 square meters) on half- to two-acre lots. Arthur says they capped the size of the homes so Summit Powder Mountain could become a democratized, harmonious environment for the community at large rather than “this über-wealthy place that is about showing off how big and bad you are.” Larger lots of up to thirty acres, however, could potentially accommodate a compound design.

Choosing a winner

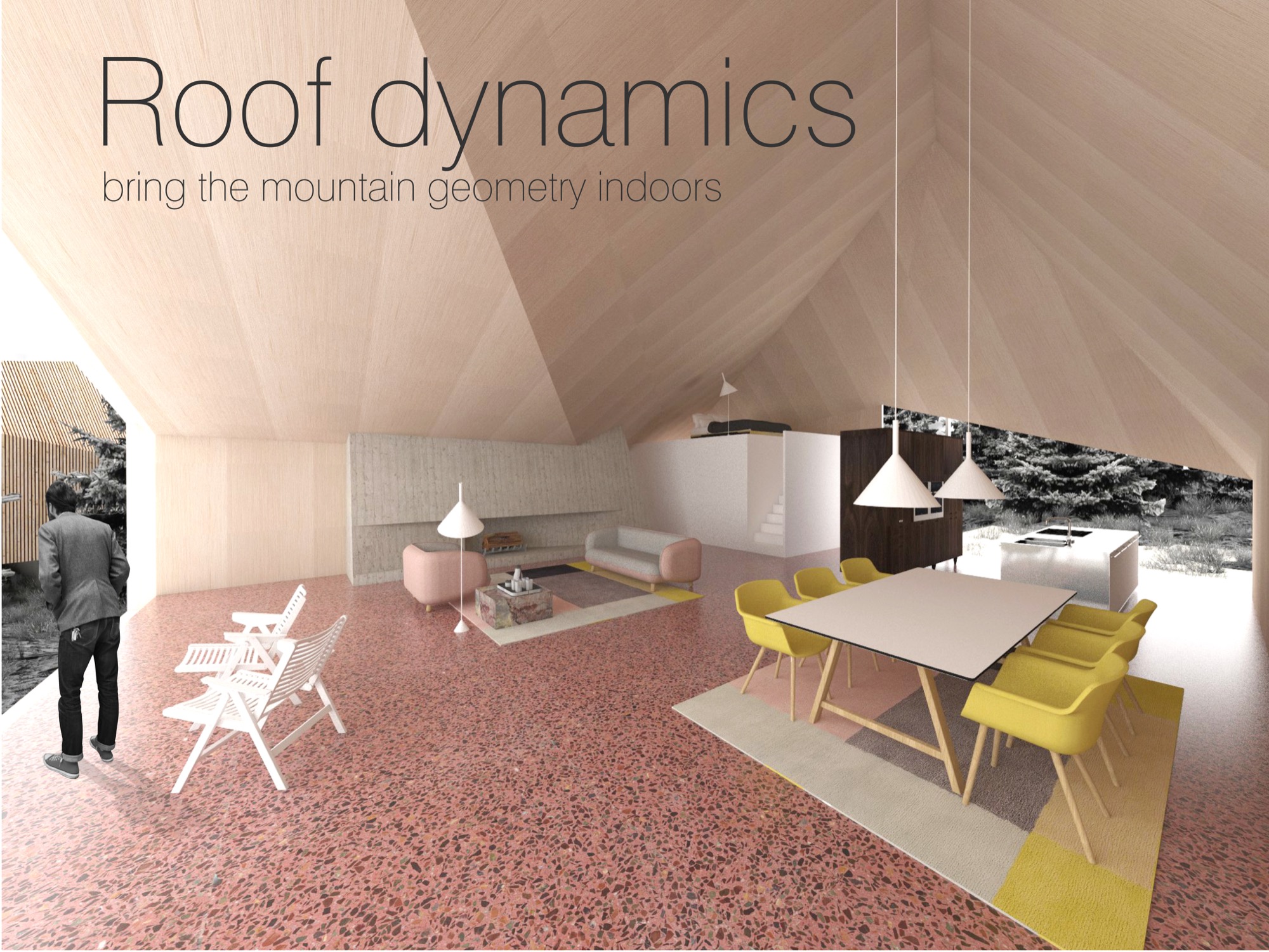

The winner: Srđan Nađ, a young architect from Slovenia. His prized design was inspired by a Summit event photo he had seen—a green meadow dotted with simple white tents, pure architecture integrated within thin cloth, pitched to create shelter from weather and wilderness. His other muse was the frontier cabin of America’s past, a simple wooden structure with a great stone chimney on the outside. “Combining both was my design concept for Summit Powder Mountain—a true connection with nature,” says Nađ, who believes “95 percent luck” won him the competition. More likely, though, he convinced the international jury panel, led by Todd Saunders of Saunders Architecture (Norway) and Jenny Wu from the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles, California), with his design’s adaptability and transformational potential. Arthur says, “Srđan did a beautiful job of meeting the criteria and applying a certain amount of aesthetic to it that really eloquently resolved that future/nostalgia-heritage/modern friction, which is at the core of what people respond to here, how they want to live in the modern age.” With its indoor/outdoor quality and what Arthur describes as “an obsession with light and views,” Nađ’s design captures the raison d’être for living on a mountain. “It’s a place to find refuge, to be inspired, to take in the natural primary source of beauty, and recreate with friends. It’s often very difficult to turn that into architecture, but Srđan took that and wrapped a building around it.”

Who is Srđan Nađ

Born to two architects in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1983, Nađ’s career choice was perhaps destined by birth. He attended a special building and engineering high school and spent his senior year abroad in upstate New York. He returned to Europe to study architecture at the University of Ljubljana, which he describes as a “boutique school” in the center of the city. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of architectural competitions and really test my ideas—and, of course, learn from my mistakes.” After practicing the craft with other studios for several years, Nađ founded Grupo H with his wife, a landscape architect. Based in Slovenia and surrounded by mountains and the outdoors, the company is dedicated equally to architecture and interdisciplinary aspects of planning and building.

“I grew up in Dubrovnik, Croatia, a great historic town by the Adriatic Sea, so I didn't have any understanding of the alpine world until my fantastic wife, a local Slovenian girl, introduced me to the alpine world of Slovenia and its natural environment,” Nađ says. “What’s special about Slovenia is that the mountains here are relatively inaccessible, and to get to know them, you need to hike a lot. Hiking is a local obsession here.”

Living in the small European country known for its mountains, outdoor recreation, and ski resorts—much like Utah—has transformed the man from the seaside. “When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective,” says Nađ. “It teaches you to admire and respect the wild nature of the alpine world. In the end, when you are put into the position to design a building for such a surrounding, all your knowledge and memories come together to create this unique combination of simplicity and elegance that a building high in the mountains demands.“

“When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective.”

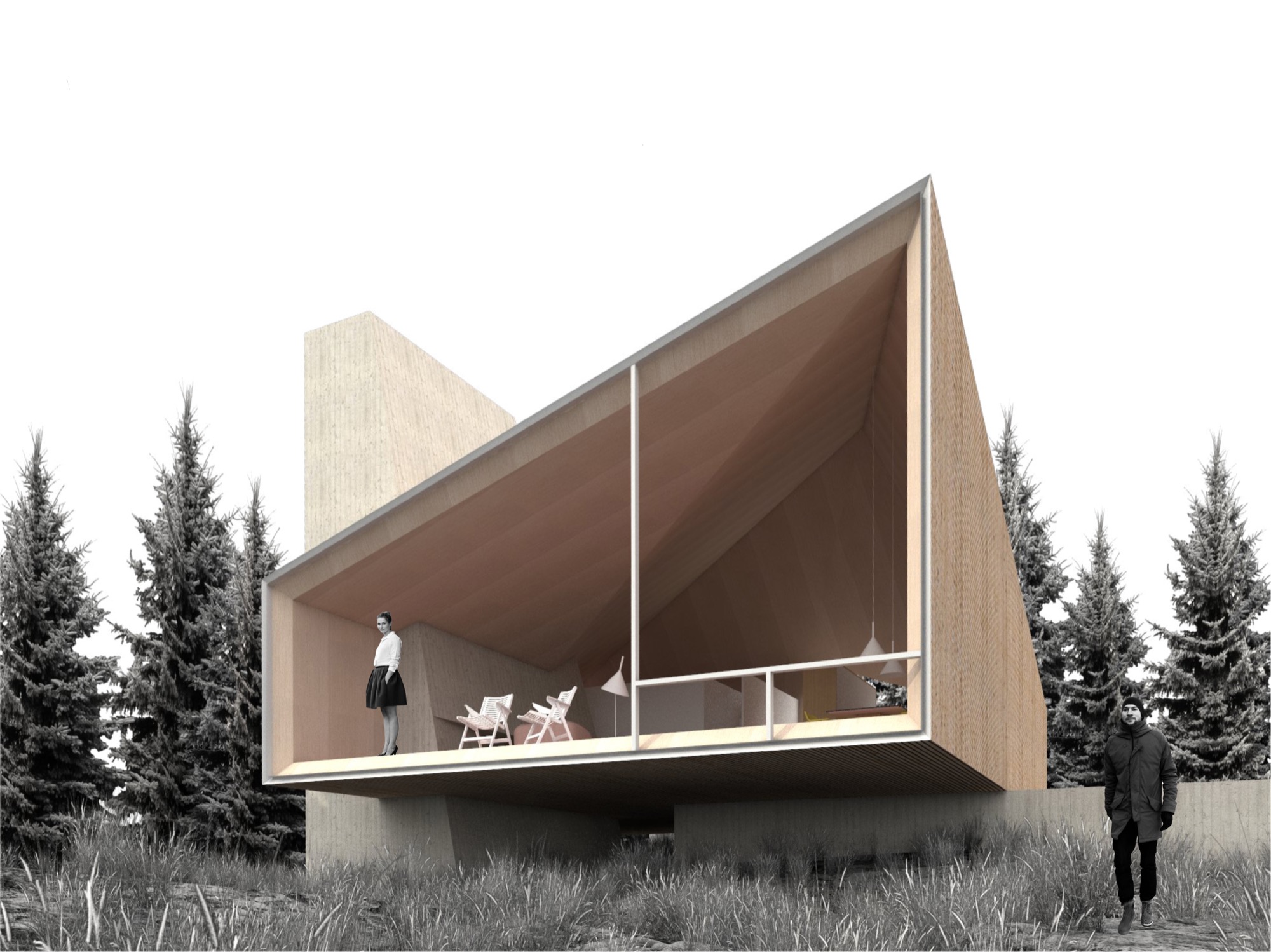

Nađ's "Wooden Tents"

His proposed cabin design preserves that tentlike lightness and unmistakable functionality that inspired him and manifests it in a permanent, habitable structure. The architect expresses this lightness through a 1.5-inch (3.80-cm) thin “skin” made from cross-laminated prefabricated wood panels, folded to create the interior space of the cabin. This folding process leaves open the sides, which are then covered in glass. Juxtaposing the transient openness of the folded skin, a monolithic stone chimney stakes the raised cabin, grounding it into the mountainside to create the permanence a tent lacks. The chimney’s body also houses the mechanicals. On the opposite side, the cabin leans on a deck that touches down to the ground. With only the chimney and the deck as supporting elements, the cabin’s footprint is small, making large earth excavations unnecessary. The triple-glazed glass walls let the sun heat the highly insulated interior. Rainwater from the sloping roof collects into storage tanks under the deck. The goal is for the cabins to be certified according to the European passive house standard and the American LEED standard.

The cabin design allows for different versions of the prototype, varying from a simple one-bedroom hut to a luxurious four-bedroom chalet. The blueprint foresees an open living/dining/kitchen area with a large fireplace. The high ceiling follows the geometry of the exterior roof, mimicking the surrounding mountain silhouette. “In all, it will be a fantastic place to come back to after a full day of skiing or a long summer hike,” the architect hopes.

Nađ’s minimalistic “wooden tents” are designed to serve as fully functional habitable structures without creating the feel of urban settlement on Powder Mountain, and they preserve the essence of the natural surroundings. Nađ strove to convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out your private piece of paradise.

His sensible solution was, no doubt, spawned by his home country and culture. “We are really humble, hardworking, and resourceful people. So that guides me to find simple, functional, and long-lasting designs for my projects,” he says, adding that the alpine cabins and shelters of the Slovenian mountains influenced his “wooden tents” for Summit Powder Mountain. “They are simple, rugged, but still graceful in unforgiving nature.”

Nađ didn’t plan to enter an architecture contest at the time he learned about the MAP design competition on an architecture blog. But the subject—a cabin—intrigued him since he thought it rather uncommon for an international contest. “You usually have a competition to design a museum, library, memorials...but houses are rare.” The premise of Summit Powder Mountain eventually compelled the young architect to enter his design. “You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.” However, he didn’t grasp the expanse of the project until he spoke with the Summit team. “I didn’t realize how important this is for the global community, as it shows a new way of planning large developments,” he says in retrospect. Nađ understood that no matter how good his cabin design was going to be, simply copying it 500 times would only create the type of cookie-cutter development that already characterizes too many mountain resort towns. “My design goal was to create a house that can be transformed—enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, have a different facade—and still preserve the overall design idea,” he explains. The “wooden tent” concept is a suggestion, one Arthur says is “a loose design that’s poetic and evocative.”

“You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.”

Building community

Summit is breaking ground this summer to build the first cabins on Powder Mountain. Furthermore, the company is planning the new alpine village, with shops and galleries, coffeehouses and restaurants, gathering venues, condos, and new headquarters for the ski resort they acquired. Arthur thinks seasonal skiers and hikers may visit the mountain and never know about Summit’s quest for settling an art, culture, and tech elite here, though it seems hard to imagine tourists coming to this creation of an idyll and doing their own thing. “We’re based on gathering,” Arthur emphasizes. “People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

“People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

What does new mountain architecture look like, act like, feel like? Only after winning did the architect from Slovenia realize how important his design was for the global community. In fact, Arthur argues that the encouraged culture of sharing is just another expression of Summit’s tacit broader understanding of sustainable living. “This isn’t ostentatious.” He points out that most members of the Summit Powder Mountain community would actually prefer to minimize their footprint by operating in a shared social space. “Rather than building large bathrooms and kitchens in their own house, people go home to sleep and to entertain a smaller group of people. Then they go out into the larger community spaces and venues to gather together. This is about collectivism and collaboration.”

But how do you curate a genial commune where strangers “gather in creativity” to become kindred spirits, collaborators, neighbors? You don’t. “We had a blunt policy for a while, a ‘no-asshole policy,’ ” Arthur reveals. In reality, they quickly came to understand that the Summit community fosters a quite self-selecting environment. “Basically, if you were obviously egocentric or self-centered, then you probably don’t belong here. People who want to participate and are ‘others-orientated’ and have the heart to expand goodness, usually work out pretty well,” he says. To the rest, it just doesn’t feel right to be there. The Summit leadership strives to strike a balance between public atmosphere and private, curated events. In the end, Arthur says, “It’s not an exclusive membership thing—it’s an overall public realm of creating a new mountain town.” △

Sense of Place: Montana modern

Nostalgia, no kitsch: A conversation with Kelcey Bingham, the insanely gifted owner of Bear Mountain Builders, about modern design in Montana

Kelcey Bingham, owner of Bear Mountain Builders in Whitefish, Montana, finds cowboy-themed log homes “really outdated.”

Nostalgia, No Kitsch

He still uses beams with reference to Montana’s Western architecture. Only his beams are typically steel. In the Ski Chalet, a mountain retreat inspired by nostalgia for ski vacations in the seventies, Bingham takes this adaptation further yet, turning a steel I-beam into a powder-room sink.

“Keep it light and bright and airy, and keep it high-tech,” is one of Bingham’s principles. The other — “anything that is not so rustic.” The Ski Chalet has quickly become his most popular work, and he’s already been commissioned to build more homes of that style. On the exterior, Bingham applied his credos by setting geometrical form with über-expansive areas of glass. The window frames, again, are steel, as is the front door, which he treated to rust by design. The roof is shaped to hold snow as an extra insulating blanket. Inside, energy-efficient, controlled lighting creates geometrical shapes on the ceiling. “Throwback style with modern conveniences,” he calls it.

“ Keep it light and bright and airy, and keep it high-tech.”

Bingham, who considers himself part builder, part architect, part artist, balances the glass, steel, and high-tech features with just enough earthy elements not to be cold. Cabinets and doors are made from reclaimed wood. The rest of the furniture is light in color, and the wood thin, to get away from the typical heavy timber look of the area’s typical super-sized mountain homes.

Creating your own throwback style at home is personal, inspired by your own memories of childhood winter vacations. Blues and rust-orange in the Ski Chalet’s fabrics, rugs, and bedding, for example, evoke nostalgia of that era.

“Instead of big dead animal heads on the wall, you’ve got vibrant art,” Bingham continues. “You don’t want too many knickknacks around, but having an appropriate amount of art is important.” Vivid details, such as colorful vases and vintage treasures, brighten up Big Sky Country’s many foggy winter days. “For us in the ski mountains, we try to find vintage ski posters,” Bingham says. Don’t be afraid to use shinier, mirrored pieces. Be selective in curating pieces from the past. “You want that nostalgic look of a seventies ski chalet, without being too kitschy.” He likes to keep a home current with vintage-inspired high-tech gadgets. “Rega out of Great Britain, for example, makes new turntables to look like they’re from the seventies.”

Recreating the Ski Chalet’s most unique decor will require a lot of luck, unless you already have an old-time ski lift seat sitting around, like Bingham had. Years back, a local ski resort was selling them off. He brought one home and was just waiting for the right use. The funky find now sets the stage inside the entry to the Ski Chalet. Not only does the seat swing like it once did high above the slopes, but it also has a purpose. “We installed an infrared heater above it, so you can sit down to take your ski boots off and warm up,” Bingham says. △

The Figure Sculptor

Alpine Modern visits Swiss-born artist Roger Reutimann at his studio in Boulder

Inspired by the human form, Swiss-born artist Roger Reutimann found his way to sculpting for the rich and the royal via a classical music education, curating art fairs, and product design.

Roger Reutimann captures elegant sensuality in his sculptures of human figures. Born in a secluded village in Switzerland, the artist, a self-proclaimed Renaissance man, has devoted himself to pursuing and mastering many art forms. His evolution from classical pianist to figurative realism painter to internationally known sculptor has secured his place as one of America’s most sought-after contemporary artists.

Early Reutimann

As a young pianist, he found himself drawn to classical composers and music that stirred his soul. He studied at the Zurich Music Conservatory and was soon performing as a classical concert pianist throughout Europe and competing in international piano competitions. Traveling provided artistic influences at an early age as he experienced Europe’s rich cultural heritage.

His love of music flowed into a career as both a realist figurative painter and a co-owner in the Forum International Art Fairs in Zürich, Hamburg, and Düsseldorf. Galleries in Zürich, Milan, and London represented his paintings, and he received innumerable awards, honors, and recognitions. Relationships with gallery owners and collectors worldwide would follow him into his future calling as a sculptor and continue to advance his reputation as a world-class artist.

The Renaissance man emerged again as Reutimann turned his creativity to remodeling his first American home in Miami, Florida, with distinctive and extensive flourishes, from mosaic tiles to stained glass windows and Tudor-style ornamental plaster ceilings. The spectacular manor has been featured in architecture magazines and leased by production companies for films and commercials.

“In the midst of remodeling the house, one day I took a sculpture class to fill the time and loved it so much I gave up painting right then. To me, sculpting is like painting a thousand paintings. It has another dimension, and, therefore, it is so much more real than a two-dimensional image. A painting is only an image of life, but sculpture is life,” says Reutimann.

“To me, sculpting is like painting a thousand paintings... A painting is only an image of life, but sculpture is life.”

Coming to Colorado

Reutimann’s love of the mountains prompted a move to Boulder, Colorado, because of its similarity to Switzerland and the expansive open spaces. “I would rather sit on my back porch watching the sun set over the Rocky Mountains than in a high-rise flat in New York City,” shares Reutimann, for whom Colorado evokes memories of his native country.

Reutimann’s sculptures are unparalleled in craftsmanship and instantly recognizable worldwide. Though earlier works are relatively small, many today tower several meters high. Small sculptures weigh nearly 200 pounds, and the six- to seven-foot-high (up to two-plus-meters) sculptures weigh in at 1,600 to 1,800 pounds (726 to 816 kilograms). The internal structures of the lifelike sculptures are a complex network with steel beams for support to withstand the elements.

Rarer Reutimanns

Art galleries and private dealers from Santa Fe to New York City have represented Reutimann’s work, and his sleek, caressable, sculptures have been carefully packed and shipped to England, Switzerland, Italy, France, Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, and South America. Today, he is represented by fewer galleries to ensure exclusivity for art patrons with his limited edition releases. Collectors include Sir Elton John, Anderson Cooper, countless private and corporate collectors worldwide, and Italian author Baroness Lucrezia de Domizio Durini, an art collector, curator, and publisher. “I see parallels between Rachmaninoff and my art. Rachmaninoff was a Russian composer and considered one of the finest pianists of all time. My art is much like music; there’s always something that can be refined,” says Reutimann. His recently completed commission for Colorado’s Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities is a sixteen-foot (nearly five-meter) sculpture named Common Unity. It reflects the art center’s nature by presenting two identical figures who might appear to be engaged in a cultural discourse.

“My inspiration is the human figure, but the interpretation of it is somewhat abstract and reduced to the essential elements which help tell a story. The source of my work comes from the human body; people are drawn to that, I suppose, because we all have one. We can all relate to it in some way,” explains Reutimann. His fifteen-piece series, Dreams, was inspired by a wax mold that melted in Colorado’s hot sun and further inspired him to create sculptures that appear human at first glance, yet abstract from other angles.

“The source of my work comes from the human body; people are drawn to that, I suppose, because we all have one.”

Body / art

The immensely popular Dreams series is a surreal interpretation of human emotions as figures fling themselves into contorted poses and postures—often reminiscent of a melted-wax figure. Reutimann has placed heads, torsos, and arms backward creating a jarring, disturbing effect that evokes a strong, visceral response for the viewer. He juxtaposes nearly perfect, yet severely distorted bodies as if broken and reassembled incorrectly. Body parts erupt in every direction. Figures hang upside down, suspended or cantilevered in space, as if falling or floating. Cast entirely in sleek stainless steel, the homogenous heads of the sculptures lack facial features and expressions, much like mannequins. “The focus is directed away from the face toward the body, and the complex dreamlike state personified within,” Reutimann offers.

In a world where discerning art patrons purchase paintings ten-to-one over sculptures, Nick Ryan, Havu Gallery’s administrator, notes that long-time painting collectors are purchasing Reutimann’s unusual and evocative figures. Ryan says they choose Reutimann’s work based on his inimitable technique of combining abstract realism with figuration, particularly in the Death of Venus, a six-foot (almost two-meter) sculpture painstakingly cast in bronze with surfaces flawlessly covered with sleek Ferrari-red automotive paint. Death of Venus is Reutimann’s interpretation of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. The spectral skull is representative of cultural shifts, and the highly saturated red paint reflects the glamour and lifestyles of modern society.

The Perception series was inspired by the artist’s visit to Egypt, and the entire series is cast in stainless steel, painted with automotive paint and buffed to a mirrorlike shine. “In keeping with abstract realism, the concept of the sculpture is about the duality of good and evil. The good has an angelic appeal and the evil has a darker character, wearing a cape with the head tucked in. My belief is that we all have these characteristics, and one can’t exist without the other,” Reutimann says.

“In keeping with abstract realism, the concept of the sculpture is about the duality of good and evil... We all have these characteristics and one can’t exist without the other.”

Reutimann’s fascination with automotive paint allows him innovations in the aesthetics of his creations. Automotive finishes require multiple paint layers buffed to a supersmooth polish until they shimmer and mirror one’s own reflection. The contemporary finish is extremely durable and lasts decades outdoors with only occasional buffing, whereas a traditional bronze sculpture with patina requires constant maintenance.

Reinterpreting americana

“My latest series is inspired by 1950s American automobiles. The fifties were all about space and speed and The Jetsons! The fantasy in concept cars goes wild; there are no limits, as there are none in art. The human body is much like a beautiful car—streamlined, organic, flowing like a dolphin in water—they’re imaginative. These sculptures have the shape of a woman but the spirit of a concept car. People see what they see and maybe it’s not my vision, which is perfectly fine. If someone is drawn to a sculpture, it’s a reflection of themselves and what their nature is, not that of the artist,” Reutimann says.

“These sculptures have the shape of a woman but the spirit of a concept car.”

The music man

Reutimann plays piano several hours daily and declares classical music to be his biggest inspiration due to its drama and emotional depth, which allow him to follow his moods. Sergei Prokofiev’s compositions were on tap the entire year Reutimann spent creating the sculptures for the Dreams series. “You need to be in a spiritual place when you create sculptures. When people talk about inspiration, what they really mean is ‘being in spirit’ so art is not a conscious act,” Reutimann points out. “You can’t learn to be inspired. Music is my subconscious inspiration.” △

“When people talk about inspiration, what they really mean is ‘being in spirit’ so art is not a conscious act. You can’t learn to be inspired.”

The Architect Explorer

Colorado architect Larry Yaw interviewed by his journalist daughter

Colorado architect Larry Yaw, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, has nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond. An intimate conversation with his journalist daughter...

Sitting on a mossy rock in a tall stand of aspens next to my dad, a couple of hours into trying to find our way from Willow Lake back to the Maroon Bells parking lot, I started gnawing on my mom’s teriyaki beef jerky from my backpack. We had left the trail long ago, and I was convinced we were lost. I must have been about eight years old at the time.

“We’re not lost, we’re exploring,” is probably how my dad, architect Larry Yaw, responded—a claim that would echo through my young years as I followed him through the backcountry of the Elk Mountains in Colorado, across Kashmir in India, and through The Wind Rivers, The French Alps, New Zealand, and beyond, along with my mom and three siblings.

We got lost a lot, sort of on purpose, in the mountains. Yet never once did I see my dad flinch in these moments. Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul. I’d watch as he’d get this shrewd sparkle of excitement in his voice as he strategized on which ridge to follow, or which drainage would lead us back to the tent, all the while managing his family on the verge of the fearful discovery that our dad, really, had no idea where we were. Yet, now, as I bring my own young family into the woods to play and discover, I realize that my dad’s resourceful and poetic confidence that has intrigued me over the years has penetrated my own psyche deeply, and I strive to encourage that sensibility to seep into my kids’ sense of adventure. And, just as he did for our family, my dad has left an indelible impression on the contemporary design ethos of the Roaring Fork Valley, as well as countless alpine communities across the Mountain West.

“Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul.”

Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond, with an exceptional roster of clients and creative business partners as his co-conspirators; and he propelled them towards the outer edges of what’s possible. If I were to guess, his clients might sum up his character with a story similar to mine, yet the chapel would be his drafting table, and the map would be the radical ideas he has hand-sketched on camel-colored paper for the artfully crafted architecture he has envisioned. Sure, during his forty-six years creating innovative designs in the mountains, his aesthetic has shifted and grown, but his passion for the rawness of the backcountry, and for the purity of connecting people to place and to nature has remained firmly in tact.

“Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond.”

As his youngest daughter, I knew all of this, sort of, but it wasn’t until we had this conversation that I truly understood the gravity of how particular vignettes throughout his life have justified, and even come to imprint themselves, on his design, his spirituality, and his personal approach of getting lost—before finding a path.

Herein lies our recent sit-down at the kitchen table, an intimate chat between an architect and his daughter:

LYR How has living in the mountains influenced your design?

LY I’m the guy who can’t stop myself from climbing up and looking to see what’s on the other side of the ridge, or from going up to the end of a valley to see what’s there. If there’s some association with exploring, and innovating beyond the expected, I’m in. Therefore, my lifestyle has been defined by, and inspired by, active outdoor living, and attached to that is the adventure of it. Adventure is a part of everything I love to do—physical, intellectual, and spiritual adventure. And, therefore, I’ve begun to regard the artform of architecture as a basecamp for this; a basecamp that is sustainable, economic in scale, but very much connected to nature as that is so much a part of the adventure of being alive and in the now, wherever here is.

“Adventure is a part of everything I love to do ... I’ve begun to regard architecture, or habitation anyway, as a basecamp for this.”

LYR Who influenced you as an architect?

LY First, the biggest influencers have been great clients of a contemporary persuasion, who relish the process of exploration and testing. There are other architects also, such as Romaldo Giurgola (“Aldo”), The Dean of Columbia School of Architecture, where I completed my Master’s studies. He would sit down and talk in these simplistic terms about the choreography that you create architecture through; the path you take and how that enriches you, and enriches the purposes of design. Louis Kahn—his work and writings inspired me.