Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Family HQ in Alaska

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner build a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner built a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

In the shadow of Denali mountain, amid Alaska’s meadows and icy streams, a former teacher and a four-time Iditarod winner built a modernist cabin as expansive as the Last Frontier.

Tens of thousands of years ago, a glacier slid its way through southern Alaska and carved out the Matanuska-Susitna Valley. Bound by three massive mountain ranges and dotted with lakes, it’s an unabashedly wild place. Hundred-pound cabbages flourish in endless summer sunshine, caribou outnumber people, and towering Denali presides over it all. "You can go 1000 miles here without crossing a road," says Martin Buser. "Most people can’t grasp that kind of freedom." A four-time winner of the Iditarod—the grueling dogsled race from Anchorage to Nome—Buser spends his days crisscrossing the landscape with his dogs. So, for his dream home with his wife, Kathy Chapoton, there was no question that the spectacularly rugged setting needed to be the driving force behind the design.

"You can go 1000 miles here without crossing a road. Most people can’t grasp that kind of freedom."

An Alaskan story

The story of how the couple met and found the site is typically Alaskan. Chapoton moved from New Orleans to Anchorage in 1979, at a time when the state government let people claim land for pennies as a way of getting back tax dollars. Soon after relocating, she joined a group of friends one day in early January to stake out the five acres allowed to each person. "It was 50 below zero, my teeth were frozen, I didn’t even know how to read a compass, and I had to walk around and literally mark the parcel," she says. "It was hilarious." Registering her claim at the office in Anchorage, she bumped into Buser, a recent Swiss transplant, and the two married not long after.

The new House for a Musher

For 20 years, the growing family (sons Nicolai and Rohn are named after Iditarod checkpoints) lived in a large house that Buser built on the land, adjacent to the kennel where his hundred-odd dogs reside. In 1996, a wildfire swept through the area: "It was pretty ugly," remembers Chapoton. As a result, people started selling off their nearby plots, and the couple snatched up 25 additional acres—including a mountaintop site that they had been eyeing for years. "It was the primo lot," says Chapoton.

Buser built a little cabin on the top of the mountain as a weekend retreat, but the combination of killer views and the couple finding themselves empty nesters convinced the pair to make that site their permanent home. They moved the cabin by truck to a nearby site (son Rohn lives there now) and called on architects Petra Sattler-Smith and Klaus Mayer of Anchorage firm Mayer Sattler-Smith to design a house. Though Buser had built several homes, the couple knew this site deserved something special. "Because of the multitude of views, we couldn’t take advantage of the site ourselves. We knew our limitations," Chapoton says.

Denali in view

Everything about the 2,450-square-foot house centers on the natural setting. "It was important to have every room look to Denali, which is the ultimate view in Alaska," says Mayer. To do so, the architects created a long, lean, L-shaped house. The blackened, local spruce cladding pays homage to the area’s wildfire, while also mimicking a glacial erratic—a nonnative rock deposited by a moving glacier. The courtyard and part of the kitchen are slightly offset, following the lines of the site’s hilltop topography, while the rest of the house points directly to Denali National Park.

"It was important to have every room look to Denali, which is the ultimate view in Alaska."

Inside

Inside, the walls are paneled in Alaskan yellow cedar, as if the charred exterior has been peeled back to reveal glowing, living wood inside. The public areas lie in one long sight line that starts in the courtyard outside, streams through the living and dining rooms and kitchen, and slips out onto the northern horizon through a wall of sliding glass. The other side of the L contains he bedrooms and bathrooms, each with its own framed outlook on Denali. Windows in the hallway and in the family room face south to let in extra sun during darker winter days. There’s also a rooftop deck, perfect for the family’s many parties—where friends grill mooseburgers and take in the star-filled sky and 360-degree views of the mountains.

Sweat equity

Lest the house seem too fancy for these frontier surroundings, it’s important to remember that Buser built the place himself over six years. Here, there are no construction codes in rural areas ("Building permit?" scoffs Buser. "What’s that?!"), and people prefer sweat equity to bank loans or subcontractors. "When Alaskans say they’re building a house, it means we’re swinging a hammer, digging in the dirt, and trimming it out," says Buser. Yet, this DIY ethos meant that Buser’s solutions were sometimes those of a would-be MacGyver. He and Chapoton charred the cladding using a weed burner and a garden hose; the 800-pound glass doors were lifted into place using Buser’s rigging of dogsled runners, pulleys, and brute strength; and he sliced open two birch trees to make the dining room table.

"When Alaskans say they’re building a house, it means we’re swinging a hammer, digging in the dirt, and trimming it out."

At the end of a typical day, Buser comes home from an 80-mile dogsled ride as the last rays of sun linger on the mountains. Inside, Chapoton (now retired from teaching) whips up a salmon meal for ten, and the gregarious couple shares wine with friends around a crackling fireplace. When everyone’s left, Buser and Chapoton will tuck into their bed, watching the vivid hues of the northern lights dance through the windows. Says Chapoton of her love of the house, "Maybe Einstein said it most simply: ‘Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.’ " △

Up and Away: 10 dream tree houses

These ten small structures make childhood dreams come true.

Who says that grown-ups can’t have tree house goals? When the demands of daily life become too much to bear, a special hideout in the sky can be your place to escape, cool off, or brainstorm in peace. Just one look at these inspirational mini-getaways and you may find yourself looking for a sturdy tree to scale.

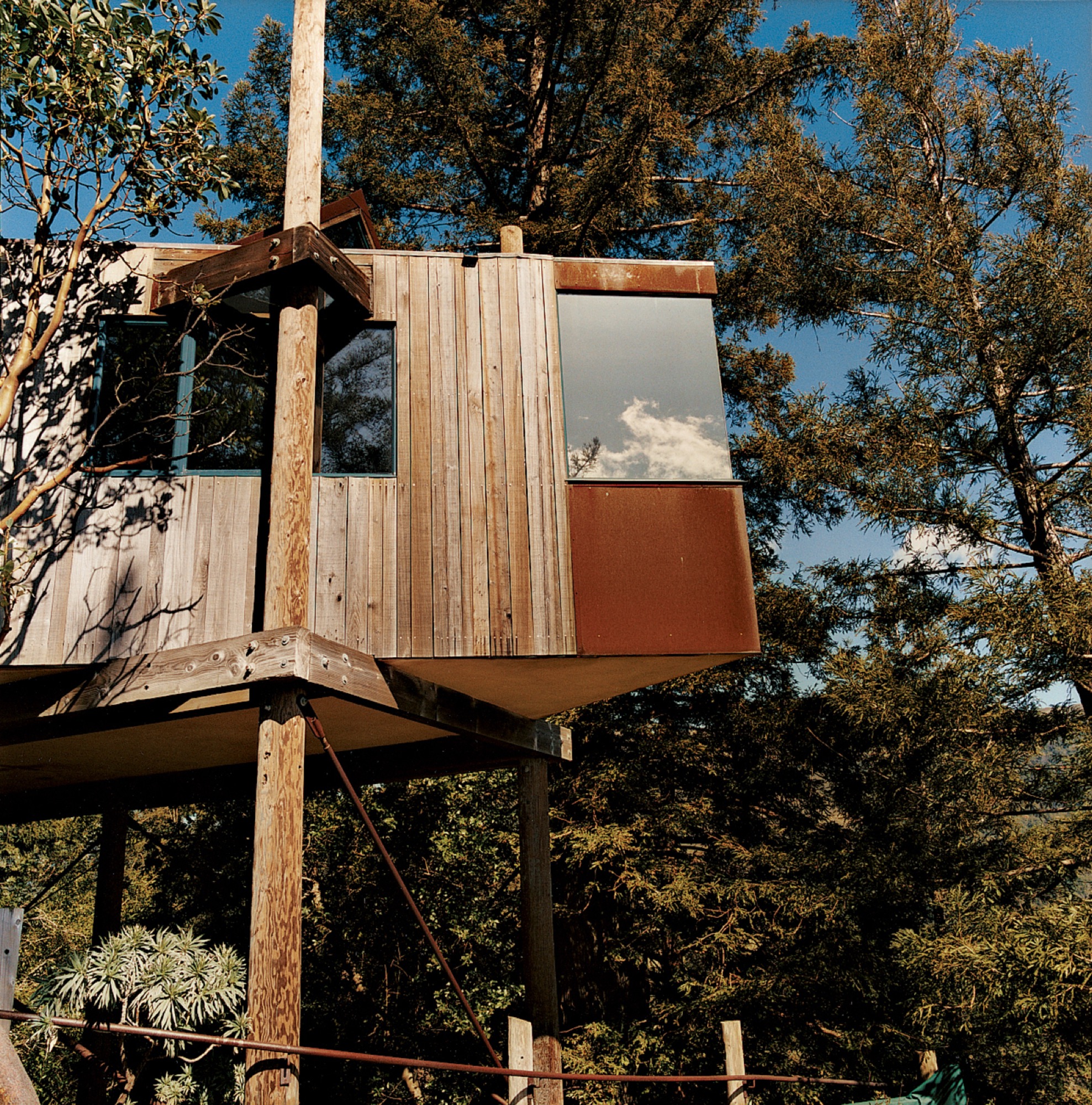

Designed by acclaimed Big Sur architect Mickey Muennig, The Post Ranch Inn consists of a series of freestanding units that showcase Muennig's contemporary organic vision. The tree houses feature Corten panels.

Dedon’s Hanging Lounger, designed by Daniel Pouzet and Fred Frety, can be an instant mini-tree house escape. All you need is the right tree to hang it from.

Treehotel’s 7th room in Sweden is a cabin that’s propped up in a pine canopy where guests can book a stay. To reduce the load of the trees and minimize the building's impact on the forest, 12 columns support the cabin. One tree stretches up through the net, emphasizing the connection to the outdoors.

Japanese architect Takashi Kobayashi of the Tree House People has been declared a "tree house master" by Design Made in Japan. Seamlessly integrating nature and design, this tiny tree house is certainly not just for children.

Inspired by the principle of biomimicry, Free Spirit Spheres’ goal is to "create new ways of living that are well-adapted to life on earth over the long haul." Based outside of Vancouver, the company specializes in tiny spherical tree houses that are works of art. You can even book an escape to spend the night in one at their forest hotels!

With the view from the Estate Bungalow in Matugama, Sri Lanka—designed by Narein Perara—you might just climb in and never want to leave.

"I had to let the trees decide how the tree house would be," explains Lukasz Kos, a Toronto-based designer and cofounder of the architecture firm Testroom. The low-impact 4Treehouse is a lattice-frame structure that respects and responds to the nature surrounding it, appearing to levitate above the forest floor of Lake Muskoka, Ontario.

At only 172 square feet, this tiny tree house in the hills of Brentwood, California, was designed by Rockefeller Partners Architects and serves as a refuge, gallery, and guest cottage.

A little more on the traditional side, this tiny backyard tree house by Sticks and Bricks makes you want to disappear for a few hours with a pot of tea and a good book.

This 128-square-foot tree house outside Baltimore was designed by architects Laurie Stubb and her husband Peter. "The outdoors here are a big playground," she says. "We had always wanted to build something for the girls that looked natural." So, in the summer of 2008, they designed this structure both for the children and for themselves. "We wanted it to have a use after they're gone—a place we can sit in and read or have a drink and entertain company." △

Sense of Place: Clean as in Whistler

Chad Falkenberg of Vancouver-based Falken Reynolds talks about modern interiors in Whistler's mountain homes and cabins

In the fourth and last installment of our "Sense of Place" series, we are talking with interior designer Chad Falkenberg of the Vancouver-based interior design studio Falken Reynolds about brining Whistler style home, no matter where you live. Whistler is rich in cedar and granite. So its natural that traditional mountain homes use a lot of both. While the wood in older homes may have a raw finish, you won’t see many log cabins in the mountains of British Columbia. The trees here are simply too massive. The granite boulders are enormous, too. People incorporate them into the structure of the house. Natural stones, in fact, are a classic element of both traditional and modern homes in the Canadian resort town.

“We try to use a lot of natural materials when we are working in Whistler,” says Chad Falkenberg, one half of Falken Reynolds, a Vancouver-based interior design studio. “It feels more authentic, closer to the earth and to the outside, which is why people go up there, to get away from the city.”

Some of his projects involve sand-blasted Douglas fir to achieve very clean lines but give the wood extra texture. “The idea with all of this is that it patinas well,” says Falkenberg. “If the wood gets hit by a tree or by skis, it’s OK.”

The studio’s work in Whistler is particularly minimalistic and sophisticated yet still achieves the cozy feel of a mountain retreat. Hard textures are mixed with softer, textile surfaces. “In the bedroom of the Aspen Drive house, we used wood furniture, but we also used wool carpet, so the whole floor feels like a sweater,” Falkenberg tells about a recent project. “When you get out of bed, you shouldn’t have to put socks on.”

The designer, who draws inspiration from years of working and traveling in Scandinavia and Southern Europe, often relies on the visual warmth of the materials. “One of the easiest tricks is to mix grays and warm colors,” to achieve the clean-lined yet warm look and feel of some of the Whistler homes he has designed. Combine a warm natural wood with a gray countertop or fabric, for example. “The two things are almost juxtaposing each other,” Falkenberg says. “It’s almost like a wood next to the cool gray looks even warmer.”

To accessorize your Whistler-inspired winter interior, go for copper and terra-cotta pots. The designer’s favorite textures are anything that feels like a sweater—the loop of a rug, wool blankets, pillows covered in chunky knits. A rougher texture, even on a hard surface like a co ee cup, also feels warmer. Leather is another great material that feels warm to the touch. It has a history to it. “Anything that evokes the natural world,” says Falkenberg.

He likes to keep things casual in a mountain retreat, as he expresses by using a wire taxidermy sculpture or resin moose heads on the wall. “I love anything that reminds me, OK I’m in a cabin, and I’m not supposed to take everything so serious.” △

Naked Naust

A dramatic cabin by Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch on Norway's wild Vega Island

Inspired by Norway’s traditional boathouses, Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch plants a cottage into Vega Island’s barren landscape—its design so minimal, it becomes dramatic.

“It’s basically just two ordinary pitched roofs,” architect Erik Kolman Janouch describes the Vega Cottage on the namesake Norwegian island. But the simple elegance of this small wooden cottage that blends so perfectly with its wild and forbidding landscape is, in itself, spectacular—not to mention the boldness and care in siting it there. What’s more, it is exactly what could be expected in this coastal region of Norway.

Not far from the house, by the seashore, stand a few of the colorful traditional boathouses—naust—found throughout Norway’s long Atlantic coast. With origins in the Viking era, this building type has withstood the test of time and weather with the island’s extremely rough climate. So, looking for another architectural typology for the Vega Cottage seemed like a futile enterprise for its Swedish architect of Kolman Boye Architects in Stockholm.

Casual observers might also miss the second most striking architectural feature of the Vega Cottage—its windows. At first, the house’s windows might appear like ordinary rectangular openings in a wall, covered with glass. But that’s just scale and perspective playing tricks, since the barren landscape of Vega Island offers little else of human scale for comparison. Standing directly in front of the house—where one’s cheeks quickly turn rosy from the cold Atlantic wind—an adult visitor can stand head to toe in the huge windows and absorb the majestic landscape. Buffeted by the wind and swept away with the dramatic views, one realizes that the windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island.

"The windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island."

A Place Apart

Vega is home to 1,200 people and lies roughly an hour by ferry out in the Atlantic from the tiny city of Brøn- nøysund on the west coast of Norway, just south of the Arctic Circle. The cottage’s site is not much more than a farmstead, marked on the map as Eidem.

This is where the man who commissioned this house, Norwegian theatre director Alexander Mørk-Eidem, has his roots. Born on the island, he has lived most of his life on the mainland, and for the past ten years in Stockholm, Sweden. That is also where he met the architect. He approached Kolman with his idea for a country house or a cottage, commonly known in Norway as a hytte. A small and simple residence in the countryside where you go on weekends and during vacations to relax and enjoy nature... something with which Norwegians, blessed with a country of stunningly beautiful mountains and fjords, seem to be obsessed.

The end of the world, as Vega feels, seems like the obvious place for a director of the stage to seek peace and quiet and to find inspiration. Mørk-Eidem jointly owns the house with his siblings, a brother and a sister who now live in London and Oslo. The house is intended as a place for solitary retreats, but also for family gatherings, since an uncle and cousins still live on Vega.

“Inside, the house is neutrally furnished to allow for nature to...” Mørk-Eidem starts to explain when I visited the house, only to get interrupted by his architect: “It’s like three paintings. There is no need to adorn the walls.”

The Cast of Characters

What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape. It doesn’t take a stage director to reach that conclusion. Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless. On the other side of the windows of the combined living and dining room lies the mighty Trollvasstind mountain, 800 meters (2,625 feet) high with a ridge that’s hidden behind milky white clouds. In the other direction the Atlantic Ocean and open sea stretch all the way to Labrador in Canada.

“What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape... Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless.”

Kolman recalls the first time he came to the island and the site, after having accepted the challenge of designing the house: “I went there in January, which is the worst time of year, weatherwise. It was pitch dark and freezing. Shockingly freezing, really. I wasn’t prepared for how harsh the climate would be.”

But nature can be kind on Vega, too. At milder times of the year, when the tide comes in during the day, the sand at the shoreline that had previously been heated by the sun warms the shallow water, allowing for some appreciated beach life. But the weather changes quickly here: from calm to a wind you can lean against in a matter of minutes. It is wise never to leave the house without the proper attire: mittens, Wellingtons, and a decent raincoat.

In contrast to the adventurous landscape and weather of Vega, the cottage interior is serene with a neutral color palette to enhance the tranquil atmosphere. Practically everything inside the house, from the walls to the bed linen, is white. The architect thinks it gives the house a hotel-like quality.

The Right Stuff

Kolman met his client through a mutual acquaintance in Stockholm. Mørk-Eidem had been looking for someone to build the house for quite some time. Realizing what a challenge it would be on this particular site, he pictured someone young, eager to take on the assignment for the experience, and Kolman fit the bill.

In addition to being one of the partners of Kolman Boye Architects, Kolman also runs a construction firm. A lucky combination since all the contractors Mørk-Eidem approached for a tender had simply refused to answer. “There was nobody who could see any joy in trying to do the impossible,” Mørk-Eidem explains.

Kolman proved to be different. In the Vega Cottage he saw nothing but an enticing challenge. Building the house on Vega was possible, but it took five years and twenty-three Stockholm-Vega round-trips by car for the architect. A total distance, he figures, that roughly equals a trip around the equator. True or not, one trip by car from Stockholm to Vega is long, time-consuming, and not very pleasant.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house had always stood on this site,” Kolman says. “What fascinates most people who come here is that you get the feeling that it’s grown out of the bedrock.”

Building on the bedrock and being gentle with the landscape also made the construction difficult. A road had to be built to the site, and building material laboriously towed over the bedrock the house stands on—not to mention the efforts to transport and install the windows. The panes are 40 millimeters (1.57 inches) thick to withstand the storms and high winds that would shake and shatter thinner glass. Residents can enjoy the spectacle outside from a quiet, warm, and cozy house, cheered by the hearth that is the heart of the lower-level’s social area. “They’re not something you can break easily,” Kolman says about the windows. “In fact, you can jump on them and nothing will happen.” Staying at the Vega Cottage, I was glad the project was graced with such a persistent architect-builder—the landscape is beautiful, but I was happy to keep the elements of nature where they belong—on the other side of the glass.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house has always stood on this site.”

Other than the pitched roof, this is a rather minimalistic house—or as Kolman says, “There is nothing that juts out, so there is nothing for the wind to grab on to.”

There is not even a railing around the terrace outside the lower level’s two bedrooms. “My sister wondered when they would be put in place,” Mørk-Eidem says. “They never will be,” he declares, adding, “This is a childproof house in the sense that nothing can be broken.”

If nothing can get broken, theoretically nothing will need to be fixed. To keep maintenance on the house to a minimum during holidays and vacations, Mørk-Eidem and his architect opted for weatherproof solutions for the house. At one stage in the project they considered black facades. But when I visited, a year after completion, the unpainted facades, which were only treated, already had their gray patina. Houses age fast on Vega.

“Houses age fast on Vega.”

The cottage owes much to vernacular architecture, but the local building tradition has always emphasized protection from the elements of nature. The island’s old buildings, placed wherever there is shelter from the storms, all turn their backs to nature and to the extreme weather. “You get very unsentimental living out here,” Mørk-Eidem tells me. “You get used to this nature, and you look at it as a kind of antagonist.”

“You get very unsentimental living out here.”

He proceeds to tell how his father reacted when he first came to the house. As an adult, Mørk-Eidem senior moved to Oslo and hadn’t lived on the island for decades. “At first, he was suspicious,” Mørk-Eidem recalls, “because he’s never been used to sitting inside and just admiring the view. For him it was a really different experience to come to a place he knows so well but to see it from an entirely new perspective.”

Hearing that this outpost can give even natives new perspectives is a testament to the qualities of this house that makes the architect say, without the slightest hesitation, that he would gladly take on the logistical and psychological challenges of an assignment like this again. △

A Platform for Living

A weekend refuge in Japan's Chichibu mountain range consists of a simple larch wood structure and two North Face tents for bedrooms

A collaboration with Dwell.com

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi’s weekend retreat, two and a half hours northwest of Tokyo, is “an arresting concept,” photographer Dean Kaufman says, who documented the singular refuge in the Chichibu mountain range. “It’s finely balanced between rustic camping and feeling like the Farnsworth House.”

“It’s finely balanced between rustic camping and feeling like the Farnsworth House.”

Designed by Shin Ohori of General Design, the structure—Setsumasa bristles at the word “house,” since his desire was for something that “was not a residence”—and its wooded surroundings serve as a testing ground for the Kobayashis, who design outdoor clothing and gear (as well as many other products) for their company, …….Research. The shelter is constructed from locally harvested larch wood and removable fiberplastic walls and is crowned with two yellow dome tents used as year-round bedrooms.

"His desire was for something that 'was not a residence.' "

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi / Photo by Dean Kaufman

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi / Photo by Dean Kaufman

Still, this is no primitive lean-to. There’s electricity, hot water, and a kitchen—not to mention iPads, Internet, and a clawfoot tub. By day, the couple trims trees and chops firewood. At night, they sit around a campfire and eat Japanese curry, listen to Phish, and balance their laptops on their knees. This is what a modern back-to-the-land effort looks like.

One North Face tent sits atop a deck; another caps the main building, which contains a kitchen and dining area.

The long, lean Kobayashi complex includes a bathroom and storage room in the structure on the far right.

Setsumasa and Hideaki toss on the rain fly. The solar panel in the foreground supplies daytime electricity.

A stockpile of wood sheltered from the elements.

Setsumasa's desire was for something that “was not a residence”

Scenes from a weekend in the woods feature many .......Research products, including camping cookware and striped wool blankets.

Translucent fiberglass panel walls form a permeable, fiber-reinforced plastic membrane between indoors and out.

Mami and Ishii Hideaki (a friend and .......Research employee) prepare lunch in the cozy main building. The room is rustic and utilitarian, with a double-decker wood-burning stove, tons of open storage, and a sink fashioned from galvanized buckets. But there’s an underlying high-design ethos: The wire baskets are handmade classics from Korbo, a Swedish company, and what looks like a paper-wrapped box in front of the stove is actually a leather cushion by Japanese artist Nakano.

Food is served in traditional camping cookware.

A view of the surrounding tree canopy.

Inside one of the Kobayashis' North Face tents.

The couple stockpiles wood under the deck.

The rooftop tent can be accessed from the interior via a wooden ladder or—for the more athletic—via a series of wall-mounted climbing holds, made by Vock and carved from persimmon-tinted hardwood.

A view of the mountains from the village of Kawakami, en route to the Kobayashis’ property. △

Window to South Tyrol

An artist and sculptor returns home to South Tyrol to converts an old farmhouse

Artist and sculptor Othmar Prenner converts an old farmhouse in the mountains of his native South Tyrol and realizes his vision of an alpine dream home—between craftsman tradition and modern art.

Othmar Prenner lounges by the spectacular panorama window, looking out into the pristine nature of South Tyrol. Modern fiberglass lines allow him to work up here, straight across from the massive, snow-capped peaks of Italy’s Vinschgau.

Technology and nature don’t contradict one another, if you ask the artist and sculptor. On the contrary. The Internet enables him to be in nature while developing new art projects and designing furniture and objects made of wood.

It is here, in his native South Tyrol, that Prenner found his way back to his craft and rediscovered the joy of creating something new with his own hands.

Every corner of his remodeled farmhouse, completed in 2011 and internationally published more than twenty times, is filled with tools, paintings, finished and unfinished pieces of furniture, and all sorts of arts and crafts. The home is vivid, and it’s cozy in front of the black steel fireplace—a focal point—suspended from the ceiling. Othmar Prenner loves the open flames, the feeling of sitting by a campfire in his living room. He dismisses ovens with glass doors and generally has his own and very clear ideas about architecture and interior design.

He helped build an atelier and gallery near Zurich, Switzerland. “I only do things I like 100 percent,” Prenner says. “That’s why I’m not interested in collaborating on big projects, where you have to make 1000 compromises.”

This was far from the case with his very personal project, the mountain retreat at home in South Tyrol. Here, the almost fifty year old was able to realize his design vision one to one and create a refuge that meanwhile has become his primary residence and studio. Rarely does he drive back to his apartment in Munich these days. “I never thought I would leave the city. I’ve lived there for twenty-two years,” he says. “My focus is here now. I love living in nature and don’t need the city.”

“My focus is here now. I love living in nature and don’t need the city.”

Art in the city, craft in the country

Prenner bought the old house in his native region near Mals twenty-five years ago. The property is part of a small hamlet that is still being farmed in a steep valley on the Reschen Pass near where Prenner grew up. In his stube, which is nontraditionally located on the second floor and combines the kitchen and dining room, he tells me he spent many childhood hours carving wood and that he has always wanted to become a sculptor since he was a young boy. His parents had little understanding for his artistic ambitions but agreed to a cabinetmaker apprenticeship. Prenner strived for more and afterward studied in Innsbruck and later in Munich. Today, his calling has become his profession, a mix of sculpture and designing furniture and objects for the home. “During my Munich years, it was definitely the arts, now I’m balancing both,” says Prenner, who recently returned from Salone Internazionale del Mobile, the furniture show in Milan where he introduced the lathed containers and boxes he sells under the brand Like a Box. The response to the boxes made from Swiss pine, the turned salt and pepper mills, and the forged knifes was incredibly positive, he reports. Even Vitra showed interest. Traditional craftsmanship is back in demand, and Milan showed it.

The dream of paradise

In his own alpine domicile, Prenner takes his love for wood to the extreme. The large window reflecting the mountain peaks pops out against the buildings homogenous, light exterior. The words “Der Traum vom Paradies” (the dream of paradise) are stamped into the minimalist fine wood facade. In the back of the small house, the roof was cut open to add a floor for the new living room. The house’s exterior as well as the interior of the grand stube are almost entirely clad in wood. A total of 250 square meters (2692 square feet) of finest parquet were installed. The larch wood came from the valley here and was specially cut so the pattern of annual rings would run ever so calmly and evenly. The wood was processed by Prenner’s brother, who still owned a carpentry shop at the time and was capable of delivering on Prenner’s discerning specifications: “Many craftsmen merely do custom Ikea nowadays, craft and industry become more and more intermingled. Unfortunately, the sense of artisanship gets lost.”

Wood as the central element was an obvious choice for Prenner. Many other details developed over the course of the building process, he tells. “It’s like working on a sculpture. Many people want to plan everything in advance and then execute one to one. That’s why I don’t like collaborating on other architecture projects.” Prenner likes to be inspired as his work unfolds. The entryway, for example, was so dark you could hardly find the doorknob. So Prenner, without hesitation, tore open the ceiling to create light, which now floods the hallway from the stube and living room above. The white marble floor brightens up the foyer still more. The stone was quarried 30 kilometers (ca. 19 miles) from here, in Laas, and counts among the hardest and whitest marble stones. “It should be self-evident to use materials from the region, and not stone from India,” Prenner notes. “There’s a new aspiration. People want to know where things come from, where materials are sourced. Things of permanence provide comfort in uncertain times.”

“There’s a new aspiration. People want to know where things come from, where materials are sourced. Things of permanence provide comfort in uncertain times.”

The former stube, where the original, 200-year-old wood paneling has been completely preserved, was converted to the master bedroom. After all, the house’s central theme is the view to the outside—and the ground floor affords prime views. Thus, the classic arrangement of stube downstairs and bedroom upstairs was simply flipped on its head. The master bedroom’s ensuite bathroom marvelously harmonizes the white marble and the larch wood. The freestanding wooden bathtub is the focal point.

Prenner preserved the old stone staircase—or its remnants—as decorative element and a nod to the old structure of the farmhouse. The modern, floating wooden stairs and the bridge—or wooden walkway—to the living room on the second floor create the contrast. “During construction, a wood plank led across there, and I found the open crossing over the hallway interesting,” Prenner reveals.

The old roof joists were preserved and support the pitch of the roof, where the living room is. Five steps lead to a narrow loft Prenner installed along the gable wall with a long panorama window, again providing spectacular views to the outside. From his desk, the artist can see the cows grazing on the lush meadow.

And the light. Prenner often missed the light when he was in Munich, particularly during the long, gray winters, he remembers. Blue skies and the special light only snow can create—here, in his house in South Tyrol, he integrates it, plays with it, lives with it.

Work and art live together

Paintings and other art objects are piled up in the living room. “This is intentional,” Prenner says. “I wanted work and art to mix. I cannot separate them anyway.” Still, he is currently building an atelier on the premises. Before, when he lived in the city, he primarily created prototypes. But now, he likes to be more hands-on in the production, together with his partner, Ingrid Seebacher. The wood for each container, which is blackened in the fire, comes from a particular tree Prenner photographed beforehand and numbered the wood sections. The photo of the marked spot from where the wood was cut is sold together with the respective object—one of the artist’s many ingenious ideas. You can discover them all over the house. Art objects made from wood waste. Leftovers from a series of chairs you assemble yourself from four pieces of wood, and which Prenner became known for. These clever chairs don’t require glue or screws. In Prenner’s home, they are part of a group of miss-matched chairs around the large dining table and around the cozy stube. “In the old days, there was no ugly furniture because it was all made from solid wood,” Prenner contemplates. “But a lot is happening now. People are sick of cheap stuff made in China.” Prenner regards sustainable and organic as standard, which shouldn’t need to be pitched on a label. Sitting by the fire, he talk about the region here around Mals, soon to be the largest community in South Tyrol that is completely pesticide free. He tells about a baker who has re-sown old spelt ears from the eighteenth century and is now selling spelt bread. Stories like this are fitting for the stube and the beautiful, pristine landscape. Looking out the window and at the mountains, I can appreciate that one man's dream of paradise has come true here. △

“In the old days, there was no ugly furniture because it was all made from solid wood.”

Othmar Prenner was born in 1966 in Schlanders, South Tyrol, Italy. After an apprenticeship in carpentry, he studied sculpture at the HTL Innsbruck, Austria, and later at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany. The website Dinge und Ursachen lists Prenner’s many projects and exhibitions. You can purchase his Swiss pine boxes and containers from the online shop Like a Box.

Othmar Prenner was born in 1966 in Schlanders, South Tyrol, Italy. After an apprenticeship in carpentry, he studied sculpture at the HTL Innsbruck, Austria, and later at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany. The website Dinge und Ursachen lists Prenner’s many projects and exhibitions. You can purchase his Swiss pine boxes and containers from the online shop Like a Box.

Utahan Utopia

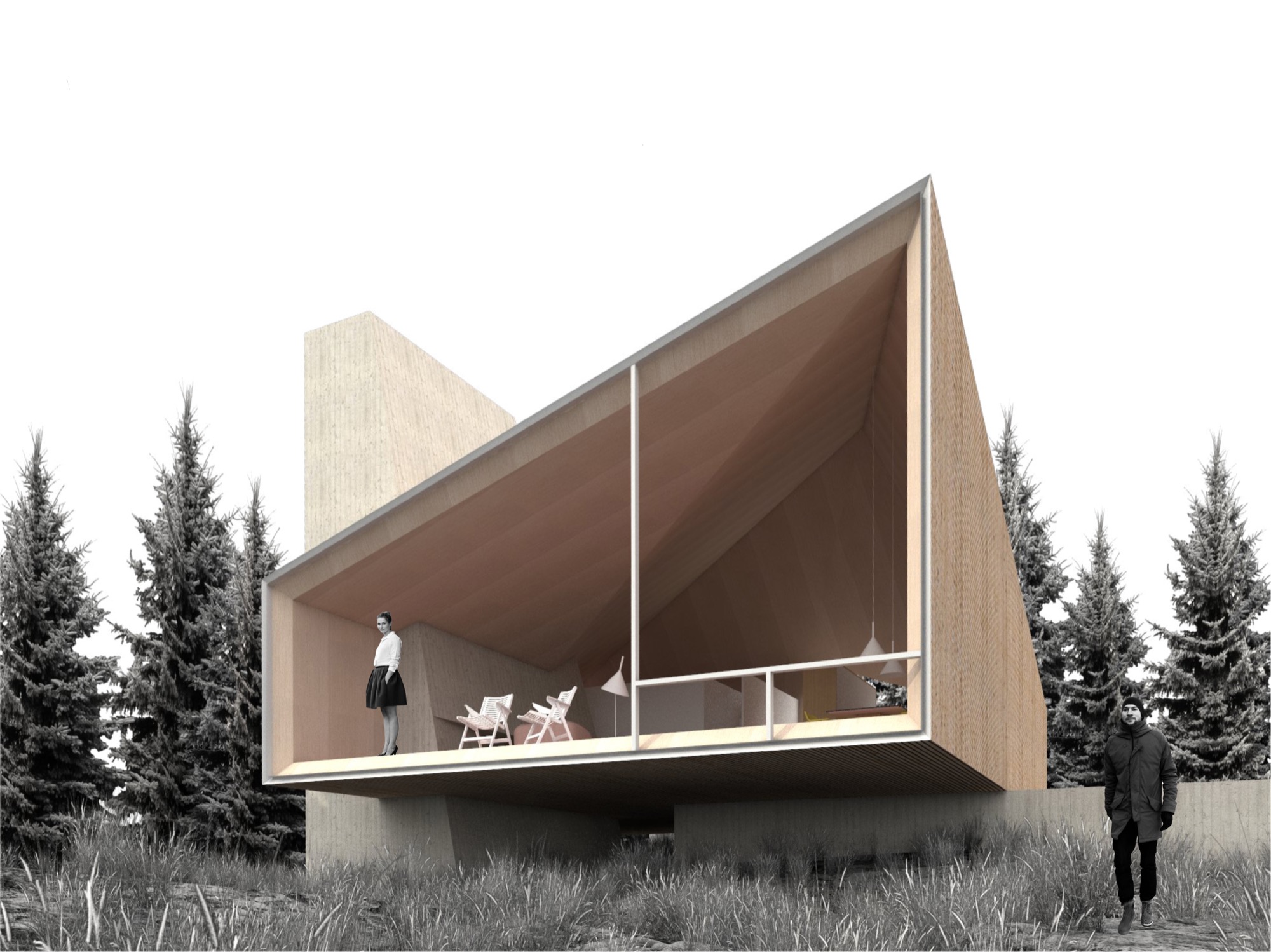

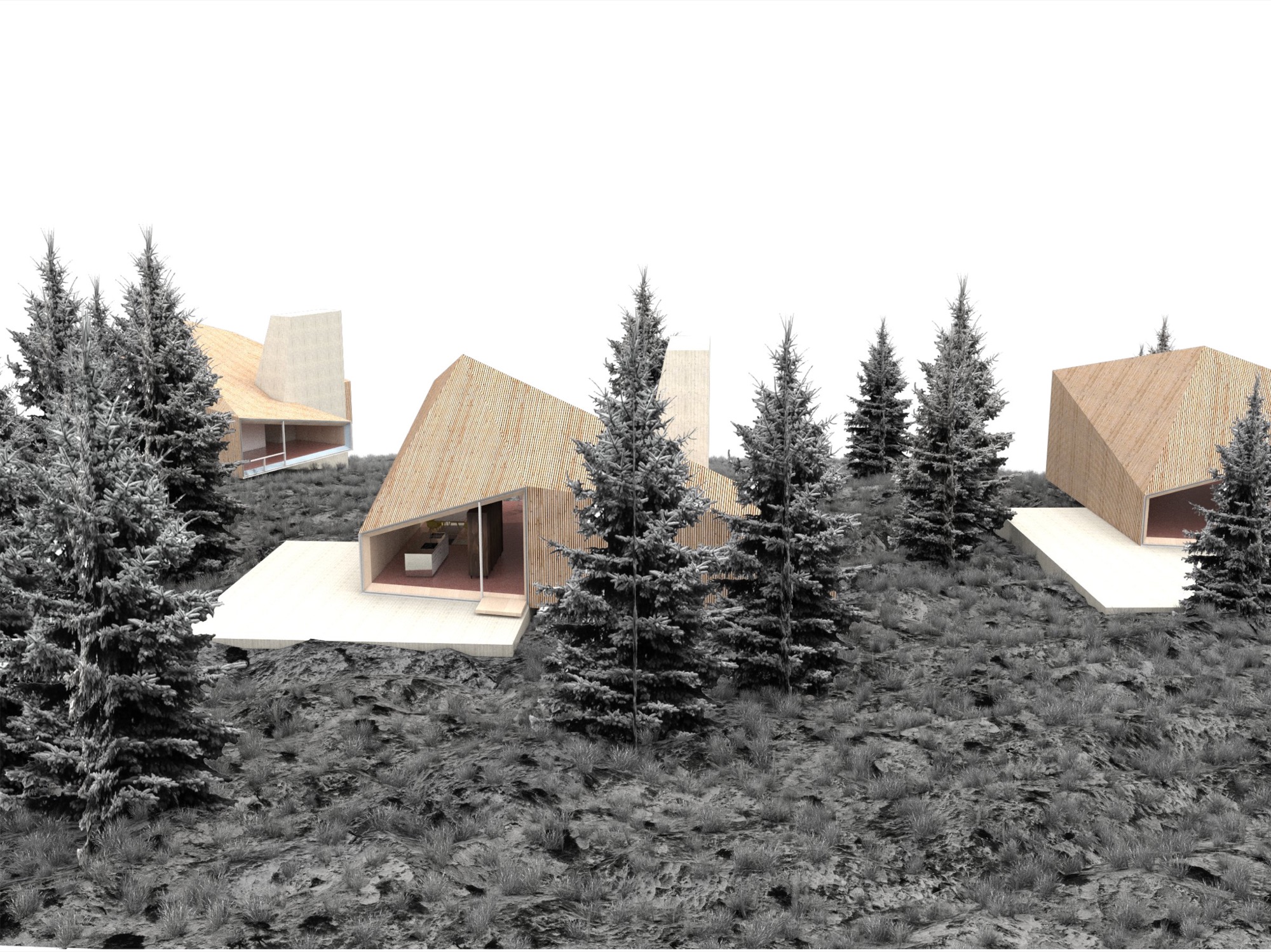

Summit Powder Mountain in Utah is a visionary colony of cabins designed by emerging Slovenian architect Srđan Nađ

A Slovenian architect’s “wooden tent” design pushes the conversation on nature-respecting modern mountain architecture and communal living on Powder Mountain, where an enigmatic group of entrepreneurs, creatives, and altruists is building a pioneering alpine village. “We bought a mountain.”

So begins the backstory of Summit Powder Mountain, a visionary colony of cabins and an alpine village being dreamed up in Utah's Wasatch Mountains.

Elliott Bisnow and the Summit Series

Behind the idea is Summit, an event business started by Elliott Bisnow, a founding board member of the United Nations Foundation’s Global Entrepreneurs Council. What began as a small gathering of a few dozen investors, business whiz kids, and creatives over a short few years grew into the Summit Series: traveling invitational events that summon hundreds of thought leaders and different-thinkers from around the world. "What would it look like if Davos and Burning Man had a baby?" The Guardian rhetorically wondered in a recent article about the Summit Series. For its latest flagship event, Summit at Sea, 2,500 chosen attendees boarded a cruise ship in Miami for a four-day conference in international waters.

Rooting down in Utah

Now Summit is building a permanent base camp for its forums—a high-alpine town for its growing tribe to come home to. Summit purchased Powder Mountain, including the ski resort that has been operating there since the 1970s, with the vision to fundamentally reimagine and experiment with how people live together, shelter themselves, and converge for the greater good. “I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world,” says Summit design director Sam Arthur, who moved to Utah to see the project through. Since buying the mountain in 2013, Summit has called on sundry architecture and design gurus, even sacred geometry to conceive this test bed for communal living. But the group still needed a cohesive cabin concept, a trademark design that considers the demands of living at 8,400 feet (2,560 meters) altitude, of building sensibly on historically mostly undeveloped, pristine mountain land that includes an elk reserve, natural waterways, and thriving wildlife. A sheep ranch was the only settlement on the mountain for the longest time.

“I’m very interested in what new mountain architecture looks like, acts like, feels like—how it responds to all the different stimuli in the world.”

Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition

Thus, Summit’s Mountain Architecture Prototype (MAP) design competition challenged the global guild of architects, engineers, artists—masters and students alike—to design sustainable cabins that embody the leadership’s ideals of sustainability, use of natural materials, and humble expression. The winning concept would guide the architectural ethos for more than 500 single-family homes, limited to 2,500 square feet (232 square meters) on half- to two-acre lots. Arthur says they capped the size of the homes so Summit Powder Mountain could become a democratized, harmonious environment for the community at large rather than “this über-wealthy place that is about showing off how big and bad you are.” Larger lots of up to thirty acres, however, could potentially accommodate a compound design.

Choosing a winner

The winner: Srđan Nađ, a young architect from Slovenia. His prized design was inspired by a Summit event photo he had seen—a green meadow dotted with simple white tents, pure architecture integrated within thin cloth, pitched to create shelter from weather and wilderness. His other muse was the frontier cabin of America’s past, a simple wooden structure with a great stone chimney on the outside. “Combining both was my design concept for Summit Powder Mountain—a true connection with nature,” says Nađ, who believes “95 percent luck” won him the competition. More likely, though, he convinced the international jury panel, led by Todd Saunders of Saunders Architecture (Norway) and Jenny Wu from the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles, California), with his design’s adaptability and transformational potential. Arthur says, “Srđan did a beautiful job of meeting the criteria and applying a certain amount of aesthetic to it that really eloquently resolved that future/nostalgia-heritage/modern friction, which is at the core of what people respond to here, how they want to live in the modern age.” With its indoor/outdoor quality and what Arthur describes as “an obsession with light and views,” Nađ’s design captures the raison d’être for living on a mountain. “It’s a place to find refuge, to be inspired, to take in the natural primary source of beauty, and recreate with friends. It’s often very difficult to turn that into architecture, but Srđan took that and wrapped a building around it.”

Who is Srđan Nađ

Born to two architects in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1983, Nađ’s career choice was perhaps destined by birth. He attended a special building and engineering high school and spent his senior year abroad in upstate New York. He returned to Europe to study architecture at the University of Ljubljana, which he describes as a “boutique school” in the center of the city. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of architectural competitions and really test my ideas—and, of course, learn from my mistakes.” After practicing the craft with other studios for several years, Nađ founded Grupo H with his wife, a landscape architect. Based in Slovenia and surrounded by mountains and the outdoors, the company is dedicated equally to architecture and interdisciplinary aspects of planning and building.

“I grew up in Dubrovnik, Croatia, a great historic town by the Adriatic Sea, so I didn't have any understanding of the alpine world until my fantastic wife, a local Slovenian girl, introduced me to the alpine world of Slovenia and its natural environment,” Nađ says. “What’s special about Slovenia is that the mountains here are relatively inaccessible, and to get to know them, you need to hike a lot. Hiking is a local obsession here.”

Living in the small European country known for its mountains, outdoor recreation, and ski resorts—much like Utah—has transformed the man from the seaside. “When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective,” says Nađ. “It teaches you to admire and respect the wild nature of the alpine world. In the end, when you are put into the position to design a building for such a surrounding, all your knowledge and memories come together to create this unique combination of simplicity and elegance that a building high in the mountains demands.“

“When you have to hike for two, three hours through untamed nature to reach a summit, you start looking at nature from a different perspective.”

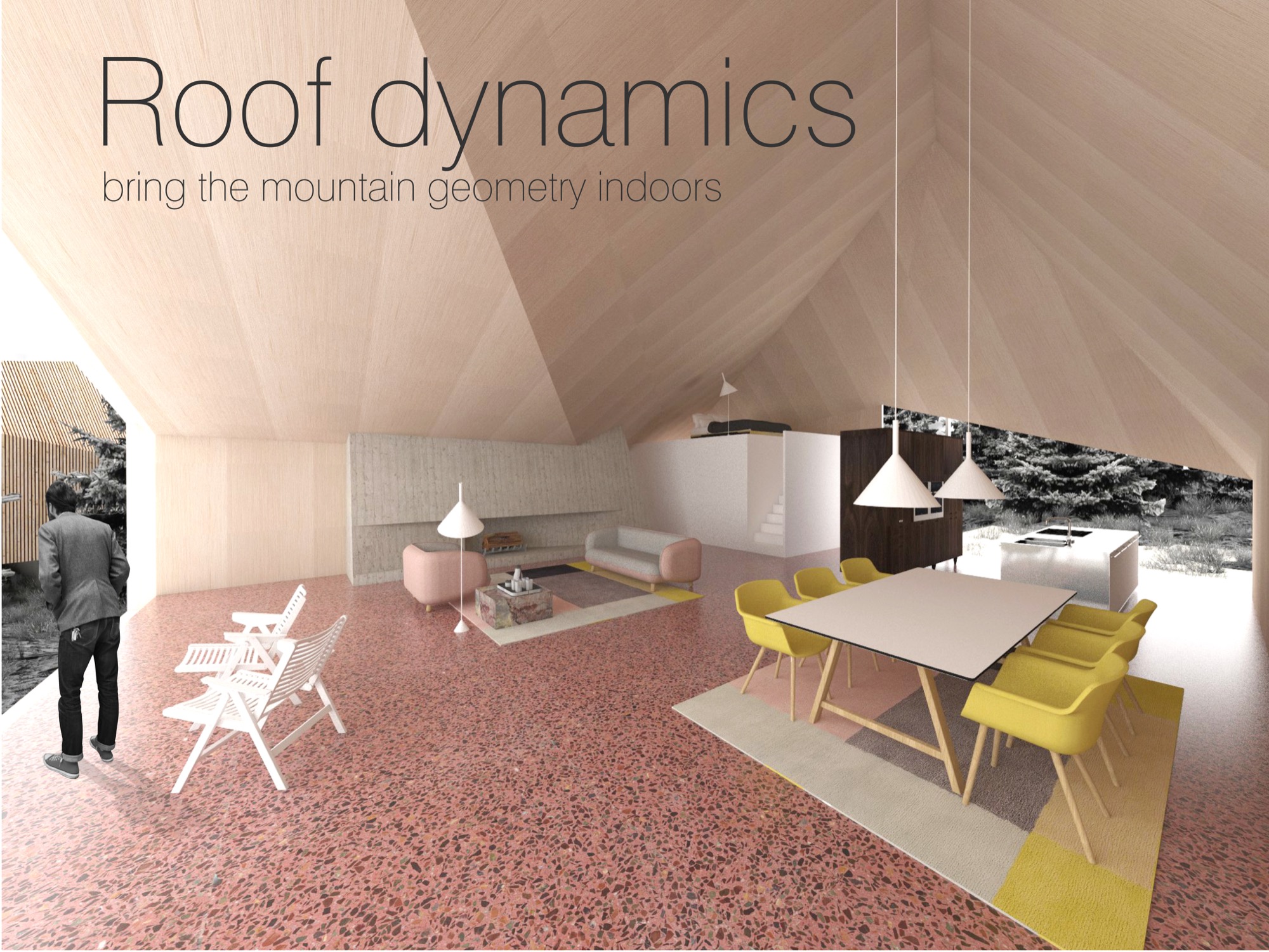

Nađ's "Wooden Tents"

His proposed cabin design preserves that tentlike lightness and unmistakable functionality that inspired him and manifests it in a permanent, habitable structure. The architect expresses this lightness through a 1.5-inch (3.80-cm) thin “skin” made from cross-laminated prefabricated wood panels, folded to create the interior space of the cabin. This folding process leaves open the sides, which are then covered in glass. Juxtaposing the transient openness of the folded skin, a monolithic stone chimney stakes the raised cabin, grounding it into the mountainside to create the permanence a tent lacks. The chimney’s body also houses the mechanicals. On the opposite side, the cabin leans on a deck that touches down to the ground. With only the chimney and the deck as supporting elements, the cabin’s footprint is small, making large earth excavations unnecessary. The triple-glazed glass walls let the sun heat the highly insulated interior. Rainwater from the sloping roof collects into storage tanks under the deck. The goal is for the cabins to be certified according to the European passive house standard and the American LEED standard.

The cabin design allows for different versions of the prototype, varying from a simple one-bedroom hut to a luxurious four-bedroom chalet. The blueprint foresees an open living/dining/kitchen area with a large fireplace. The high ceiling follows the geometry of the exterior roof, mimicking the surrounding mountain silhouette. “In all, it will be a fantastic place to come back to after a full day of skiing or a long summer hike,” the architect hopes.

Nađ’s minimalistic “wooden tents” are designed to serve as fully functional habitable structures without creating the feel of urban settlement on Powder Mountain, and they preserve the essence of the natural surroundings. Nađ strove to convey the notion of living in nature rather than intruding upon the alpine landscape to stake out your private piece of paradise.

His sensible solution was, no doubt, spawned by his home country and culture. “We are really humble, hardworking, and resourceful people. So that guides me to find simple, functional, and long-lasting designs for my projects,” he says, adding that the alpine cabins and shelters of the Slovenian mountains influenced his “wooden tents” for Summit Powder Mountain. “They are simple, rugged, but still graceful in unforgiving nature.”

Nađ didn’t plan to enter an architecture contest at the time he learned about the MAP design competition on an architecture blog. But the subject—a cabin—intrigued him since he thought it rather uncommon for an international contest. “You usually have a competition to design a museum, library, memorials...but houses are rare.” The premise of Summit Powder Mountain eventually compelled the young architect to enter his design. “You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.” However, he didn’t grasp the expanse of the project until he spoke with the Summit team. “I didn’t realize how important this is for the global community, as it shows a new way of planning large developments,” he says in retrospect. Nađ understood that no matter how good his cabin design was going to be, simply copying it 500 times would only create the type of cookie-cutter development that already characterizes too many mountain resort towns. “My design goal was to create a house that can be transformed—enlarged, scaled down, rearranged, have a different facade—and still preserve the overall design idea,” he explains. The “wooden tent” concept is a suggestion, one Arthur says is “a loose design that’s poetic and evocative.”

“You could see that they are not planning to do a typical commercial development, but start with a clean slate and do things right.”

Building community

Summit is breaking ground this summer to build the first cabins on Powder Mountain. Furthermore, the company is planning the new alpine village, with shops and galleries, coffeehouses and restaurants, gathering venues, condos, and new headquarters for the ski resort they acquired. Arthur thinks seasonal skiers and hikers may visit the mountain and never know about Summit’s quest for settling an art, culture, and tech elite here, though it seems hard to imagine tourists coming to this creation of an idyll and doing their own thing. “We’re based on gathering,” Arthur emphasizes. “People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

“People gather in creativity to change the world. People don’t come up here for solitude, but for increased interaction.”

What does new mountain architecture look like, act like, feel like? Only after winning did the architect from Slovenia realize how important his design was for the global community. In fact, Arthur argues that the encouraged culture of sharing is just another expression of Summit’s tacit broader understanding of sustainable living. “This isn’t ostentatious.” He points out that most members of the Summit Powder Mountain community would actually prefer to minimize their footprint by operating in a shared social space. “Rather than building large bathrooms and kitchens in their own house, people go home to sleep and to entertain a smaller group of people. Then they go out into the larger community spaces and venues to gather together. This is about collectivism and collaboration.”

But how do you curate a genial commune where strangers “gather in creativity” to become kindred spirits, collaborators, neighbors? You don’t. “We had a blunt policy for a while, a ‘no-asshole policy,’ ” Arthur reveals. In reality, they quickly came to understand that the Summit community fosters a quite self-selecting environment. “Basically, if you were obviously egocentric or self-centered, then you probably don’t belong here. People who want to participate and are ‘others-orientated’ and have the heart to expand goodness, usually work out pretty well,” he says. To the rest, it just doesn’t feel right to be there. The Summit leadership strives to strike a balance between public atmosphere and private, curated events. In the end, Arthur says, “It’s not an exclusive membership thing—it’s an overall public realm of creating a new mountain town.” △

Architecture, Made On Site

The husband-and-wife founders of Scott and Scott Architects design-built their own off-grid cabin with the adventurous spirit of the powder boarders they both are.

Built by husband-and-wife architects for themselves, an off-grid cabin in the mountains of Vancouver Island captures the adventure and freedom of powder boarding, free of rigid ideas.

David and Susan Scott wanted to make architecture. But not in the way one imagines married architects making architecture for themselves — drawings of their dream mountain retreat, years in the drawer, just waiting for the right building site. No. Building their own alpine cabin, the Vancouver-based architects wanted to design and build in a singular act.

In 2006, a longtime friend led them to a piece of land he’d come upon when planting trees at 4,265 feet (1,300 m) above sea level, on the northern end of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. “We had never been on the snow in the area until acquiring the building site,” says David Scott, speaking for the adventurous couple. “We fell in love with it at first sight, and the people and terrain are really special.” With almost 50 feet (15 m) of annual snow accumulation, the remote community-operated alpine recreation area of Cain is known for legendary powder.

At the time, the couple, who met in architecture school in Halifax, Nova Scotia, worked for established firms and spent long hours in offices, drawing. “We have a love for building and being outdoors,” says Scott, who appreciates drawing as an important part of design. Now building their own off-grid cabin, however, they wanted to channel the freedom they feel when powder boarding into an immediate design process centered in adventure and not heavily in rigid plans. “We began the project with a desire to work with a greater level of freedom, where the specifics of the site and available materials would inform the work in a direct and unfiltered manner.”

Scott and his wife knew they had a narrow window in life, before having children, to complete construction on their own on long weekends and holidays, and with help from friends.

“We began the project with a desire to work with a greater level of freedom, where the specifics of the site and available materials would inform the work in a direct and unfiltered manner.”

Hand in hand: Design and construction

Inspired by the materials available around the site and the environmental conditions, construction was planned to avoid machine excavation, to withstand the very deep annual snowfall, and to resist dominant winds. Accordingly, the structure was elevated above the height of the accumulated snow on the ground. “The use of full-length, unsawn logs provided us with the ability to get height in a manner that used the wood’s strength the same way Douglas fir spar poles are used as sail masts,” Scott explains.

The cabin, primarily constructed from Douglas fir, gets more refined from the outside in. The columns are unworked logs, the beams and joists are rough, bandsaw-milled, and the walls, floors, and ceilings are clad in planed boards. The cabinetry is made from construction-grade fir plywood. The exterior is clad in cedar that has weathered to the tone of the surrounding forest. Both woods are harvested in the area.

The roof form began with a simple gable, rotated to direct the snow off the back of the cabin. A half-dormer was then introduced over the entrance to direct snow away from it, funneling the snow into the prevailing winds.

Family life at the cabin

Today, childhood memories are already being made at the cabin. The Scott family now includes two young daughters, who Scott says are both on skis and love the snow.

Much of the approximate 1,075-square-foot (100-sq-m) cabin’s interior is designed and made by Scott and his wife. The main living space is small, and the family spends much of the time on the long, cushioned bench eating, playing games, and relaxing from a day on the snow. “Our favorite spot is by the large window,” says Scott. “Both for the ever-changing view of the forest, but also in appreciation of the effort that went into its installation.” He drove the glass overnight on a rented flatbed and hand-positioned it with a group of friends the next day — “an incredibly smooth effort, given its size and weight.”

The remote site is directly accessible by gravel road five months of the year. During the other months, equipment and materials are brought up by toboggan. There is no electricity, and a wood stove provides the heat. Water is collected from a local source and carried in. The Scott family cherishes the simple lifestyle the mountain hideaway affords. “We enjoy the solitude of not having cell phones and gadgets around to distract us,” says the architect, who finds “a wonderful freedom” in seeing no bars of coverage on his phone. “This is an incredible place for our daughters to love being in the mountains as much as we do.”

“This is an incredible place for our daughters to love being in the mountains as much as we do.”

The powder hounds come up here as many weekends as possible during the winter, but they also love the warmer temperatures in spring when snow is still plentiful. “It’s incredibly peaceful,” Scott says. “The fall is fantastic when the blueberries are ripe, and we try to spend Thanksgivings on the mountain, splitting wood and enjoying dinners with friends.”

Adventure by design

The off-grid cabin was David and Susan Scott’s foundation project and formative in their desire to start their own architecture practice, Scott and Scott Architects, with the goal of spending more time in the mountains. To both, making architecture on site is ultimately the most direct, enjoyable way of working, and one that provides the greatest opportunity to understand materials and detail resolution and evolution. Today, the firm is working on projects in Whistler and Squamish, and in their province’s interior high country. “We love working in these challenging locations where adventure is the reward,” says Scott.

(Alpine Modern has covered the A-frame cabin Scott and Scott built in Whistler for a young family of skiers and snowboarders.)

What’s Inside?

Architect David Scott opens the door to the off-grid snowboard cabin he built with his wife on Vancouver Island to show his three most treasured artifacts hidden inside.

The cast-iron pot

“We have a Björn Dahlström-designed cast-iron pot we slow-cook many meals in on the wood stove, which is essential to how we live when we are [at the cabin].”

Get your own: Björn Dahlström designs pots and casseroles for the Finnish company Iittala. Dahlström’s current line is stainless steel, but cast-iron pots and Dutch ovens similar to the one in the picture are available from brands like Le Creuset, Sur La Table, and Lodge.

The splitting maul

“I have a love for Swedish axes. Of my collection of over 100, the most used and loved is the Gränsfors Bruk splitting maul, which powers through the yellow cedar rounds. It is a beautiful object from a company we greatly admire. Whenever cutting wood, I look at the stamped initials of the smith that made it, with appreciation for his work and respect for a very old company which values and celebrates the workmanship of the individuals within it.”

The Gränsfors Bruk splitting maul’s head is heavier than the head of splitting axes, and the poll is designed for pounding on a splitting wedge.

The blanket

“We love our Hudson’s Bay blanket, which was a wedding gift from the architect I worked for for a number of years, before we began our own practice. I’ve often thought that a Bay blanket should never be bought for oneself and is something that carries meaning as a gift.”

Buy it for someone: Woolrich offers Hudson’s Bay Point Blankets under the offcial license of the historic Hudson’s Bay Company. The legendary blankets have kept generations of trappers, hunters, fur traders, and Native Americans warm and comfortable. 100-percent wool, loomed in England. △

One Hundred Years of Swissness

A renovation of a 1912 chalet so beautiful it spawns an interior design company

In 2012, Virginie Confino, a photo editor, and her science journalist husband Bastien fall in love with a 100-year-old chalet in Val-d’Illiez, near the Portes du Soleil ski resort in the Swiss Alps. Without any prior knowledge in building or renovation, the couple abolishes their resolution not to entrap themselves in any kind of serious remodeling project and deconstructs the faded chalet. The result was so beautiful, it propelled Virginie into the new adventure of launching her own interior design business, Gris Souris.

The story in her own words...

We were looking for a holiday home for our family of four. We visited some chalets, but none of them felt right for us. Until we found this one. We fell in love with the balcony at first sight; its whimsical railing looks like lace.

Inside, the chalet was old and untouched since the 1960s. The walls lacked any sort of insulation, the house had no heat and a ladder in the living room was the only way to reach the upstairs, no stairs.

Intention out the window

Right away, we had a vision for how we would transform this chalet. Although, when we first began searching for a property, we had no intention to throw ourselves head-first into a renovation project. Our limited budget meant that we had to do almost all of the work ourselves. What’s more, neither of us had any experience even close to remodeling or construction — me a freelance photo editor for the press and my husband a science journalist. But Bastien has always believed, “Anything is possible.” And we did it!

My husband learned a lot from books, the Internet and YouTube videos, and I joined him at the chalet two days a week for a year and a half. We required professional help with the masonry in the entrance, because the rain was coming in, with the terrace outside, and with the heating and plumbing.

We virtually gutted the inside of the house. We just wanted to keep some of the old elements, such as the old wood floors, stairs and doors. Once we finished insulating the house from the bottom to the roof, we put the old wood back on the walls. We used a lot of wood on the inside, old wood, and slate for the bathroom floors.

1912 on the outside, Swiss modern on the inside

The chalet is a mix of old and modern. Because we have a big entrance, I wanted to do something special there. We chose a transparent door that gives view to the log wall, which is a decoy we created by cutting about 4000 logs of wood into five-centimeter pieces, 15 centimeters at the top. We dried the logs and fixed them together. The wall alone took ten days of work.

We remodeled the kitchen simply by changing the cabinet doors and painting the walls. Almost all of the furniture is from IKEA. We didn’t want to furnish the chalet with special pieces because we are renting it out when we are not using it.

Bastien built the dining room table himself, because we couldn’t find one that was three meters long and not too expensive. We painted the table top with chalkboard paint so we can write on it when we play games.

The dining chairs are old Tolix chairs that sat outside for a long time, which gave them the perfect rust-like patina for the chalet. Two Butterfly chairs and Tolomeo Artemide lights on the walls, not much else. We incorporated old sleds we found in the cellar into the decor.

Outside, we have a nice terrace with amazing mountain views of the Dents du Midi. We enjoy looking at this mountain range while we take a Swedish bath outside, even when it’s snowing.

Gris Souris

Chalet Le 1912 became my “business card.” Once the renovation was finished, friends started asking me for interior design advice and even wanted me to renovate their chalet. Soon, my new adventure began, and I created Gris Souris, my interior design company in Lausanne. △

Photos by Myriam Ramel Baechler / Lumière du jour

Haus Z2 in Bayrischzell

The modern vacation home by Beer Bembé Dellinger reinterprets traditional Bavarian-alpine forms and materials

The large glass façade in the front and glass oriels on both sides of the house ensure a scenic view from the foot of the Wendelstein down to the valley from almost every room. The house's oblongness is inspired by the Alps and represents a reinterpretation of the characteristic traditional Bavarian barn. At the same time, the design concept addresses the site's narrow proportions.

The house's materials are also influenced by Bavarian-alpine traditions — mainly larchwood in form of tongue-and-groove boards for the façade and as shingles on the roof.

Lead architects were Felix Bembé (conception) and Michael Wondre (project leader and construction supervisor). △

Hideaway Cabin

Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta in Norway

Seemingly growing from the mountain, the impossibly small Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta shelters up to 21 people. The Norwegian firm Snøhetta creates architecture, landscapes, interiors and brand design. And in this case, incredibly small architecture with a big task.

Family shelter

The project was commissioned on family farmland by Osvald Bjelland, who is chairman and CEO of the global business advisory Xyntéo and founder of The Performance Theatre, a leadership think tank.

The challenge in designing the Åkrafjorden hunting lodge on a fjord, high in the mountains above the village of Etne in Hordaland, Norway, was indeed its small size in the face of its intended use: The mountain hut was to be maximum 35 square meters (ca. 377 square feet), with the capacity to shelter up to 21 people (the same number of beds as at the family's farmhouse down in the village). Plus, the off-grid structure with no running water needed to look like it had always been there.

Only accessible by foot or on horseback, the remote lodge’s setting is beautiful, isolated, beside a lake in the untouched Nordic wilderness of West Norway.

One important part of the design concept was to integrate the hut into the landscape. Thus, the small hut’s shape, orientation and materials are influenced by the terrain’s characteristic composition of grass, heather and glacial rocks. In winter, the cabin becomes another brown fleck — like the rocks — in mounds of snow.

Modern expression of ancient traditions

The structure consists of two curved steel beams, covered with a continuous layer of hand-cut logs of timber — a fusion of modern architectural expression and the style of traditional Norwegian mountain cabins. The roof, with its organic form, “grows” out of the landscape and is overgrown with grass. The materials of the facades are local stone, tar treated wood and glass.

To make room for a surprisingly large number of guests in such a tiny space, the architects found inspiration in ancient lodging traditions: The space in the center serves as gathering place, and the beds along the walls provide a spot to sit comfortably around the middle of the room in the evening — one piece of furniture for socializing, eating and sleeping. A narrow nook by the entrance accommodates cooking equipment and storage. △

Narrow Escape

Falling in love with an impossibly narrow lot on a mountain village's main street, A Denver architects builds a 15-foot-wide weekend home for his adventurous family

Incited by a seemingly impossible building site in an old railroad town above Vail Valley, Colorado, a Denver architect designs a 15-foot-wide sustainable mountain getaway as a speculative investment for sale. Then his adventurous family falls in love with the home. It was an eyesore. Passersby merely saw a ramshackle trailer overstuffing the 25-by-100-foot (7.5-by-30-m) lot on Main Street in Minturn, Colorado. Yet, André Vite spotted an opportunity.

The campus architect at the University of Colorado Denver and his wife, Ginger Borges, an oncologist at the University’s medical school, have a weakness for obscure properties. That evening three winters ago, however, they maintain they were not scoping out a new venture at all. The couple and their preteen sons, René and Niko, were headed to the old railroad town up Eagle River for dinner after a day of skiing in Vail. “We drove through Main Street Minturn, which is a town we go to all the time, and there was a mobile home for sale that was just totally wedged in and awkward looking,” Vite remembers.

Even though he didn’t know what to do with it at the time, the architect wanted that piece of land. And he got it without difficulty because the city planners had been eager to get that blot off Main Street.

The draftsman went home and started sketching.

S(e)izing the Opportunity

The lot’s appeal was twofold: It was located right on the town’s main stretch and it was zoned for mixed use. “From a planning and zoning standpoint, it was a fantastic opportunity,” says the architect and urban designer, who also heads his own practice, the Vite Collaborative. (Or, as he describes it, “A bunch of friends working on unique projects together.”) If for nothing else, Vite purchased the property at a propitious time. The shops along Main Street had been expanding in that southern direction in recent years. Thus, Vite had originally designed the project as a residential spec home with the option for retail or commercial space on the ground floor.

While the sliver of land overlooks the principal artery of town life on the Main Street side, the opposing end couldn’t have more different surroundings — a quiet residential street with community gardens across the way. “From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building,” Vite recalls. “Both facades relate to the context of the side they are on.”

“From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building.”

Yet another challenge the building site posed was the 10-foot grade change between the two frontages — an entire story difference, front to back. That was not all. The town’s zoning laws required a 5-foot setback from the property line. The house could be only 15 feet wide.

Fortunately, the neighbor’s garden to the south and a driveway next door to the north give the narrow site extra breathing room. “It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light,” Vite says.

"It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light."

Unconstrained creativity on 15 feet across

The building constraints — the narrowness, the contrasting major facades, the steep slope — only spurred Vite’s imagination and inspired innovative solutions. How did he create a modern living space — an entire three-story house — with 15 feet (4.6 m) across to work with? The architect’s answer was a structural steel frame, an element adopted from commercial construction, which gave him the structural freedom to engineer large open spaces on the inside. “It’s a steel moment frame structure with three beams that go all the way down the building. Then there is a steel beam across the top.”

The steel beams manifested what would become part of the narrow house’s legacy, and with it, a close relationship between Vite and the local builder, Brian Beckett. “When he was erecting the moment frames, Brian called me and said we can’t put the roof on tomorrow,” Vite says. One of the moment frames had been a quarter-inch off plum, which was still well within building tolerances. As might be expected from the sanguine architect, the holdup was anything but a point of contention; on the contrary. “To have a guy who takes this that seriously was just really important to me. I knew I was going to get a great building from him,” says Vite. “The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

“The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

Actually, there was one moment during construction that did stop the architect in his tracks. After Beckett put the roof on the now-perfect steel frame, he took a picture and sent it to his client in Denver. “It looked like a tube; like you wouldn’t ever want to live in anything like it,” Vite remembers his initial reaction. “It wasn’t until we started finishing it out that it turned into what we’ve got. But that was a scary point, because it was so narrow.”

Family first

By the time construction was completed, the next ski season was approaching. Vite and his family had frequently driven up from Denver to ski in the Vail Valley during previous winters. “We decided we would use the house for that ski season,” Vite says about the investment property he had just finished. “We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

“We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

The unique house itself wasn’t the only reason the family never wanted to move out. “We absolutely fell in love with Minturn. It’s the real authentic mountain community between Beaver Creek and Vail, where you have all these people who are transient and vacationing. The people in Minturn are really the ones who keep that valley going,” says Vite about the mountain town’s thousand or so residents.

What’s more, Borges not once considered her husband crazy for building this improbable house. “We’ve been married for twenty years,” Vite laughs. “She is used to that.” And attuned to narrow dwellings she was. The first home the couple restored and lived in together was a townhouse in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood that was only 14 feet wide. “She’s getting an extra foot,” Vite exclaims, insisting his wife was thrilled about the idea to keep the Minturn house. Now the four escape up here nearly every weekend, year-round, to fish, drive their go-kart, hike — or ski in winter.

Open space to monkey around

Since completion, the house has evolved into a fun destination in its own right for the adventurous family. “The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open,” Vite says. Scarcely any interior walls partition intimate bedrooms and private bathrooms from the open, free-flowing floor plan. At the bottom, the concrete foundation encases a below-grade guest bedroom and bathroom on the dwelling’s Boulder Street side. Because of the steep slope, the opposite end is above ground, where the garage faces Main and can be extended out to the street for a future retail space.

“The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open.”

The ceiling of the modern living room on the second floor rises two stories with an overlooking loft, the parents’ open bedroom. The boys’ west-facing bedroom is tucked behind the “master” (or in front of it, depending on which frontage you interpret as the face of the house).

The family spends most of their time together in the open living space with the curved white couch. “We take this big picture off the wall and project movies onto the wall.” The cork-floored main living area flows outside through a folding glass and steel wall that opens up to the deck. A minimal dining area in the middle transitions into the kitchen, Vite’s favorite spot in the house.

“But what the kids love is this 26-foot space here,” says Vite, pointing at the high living room ceiling, where he mounted a climbing rope. “They get to climb up this wall that’s all blocked with wood, ready to put in finger holes for a climbing wall.” Climbing is indeed the boys’ favorite indoor pastime. “They climb everything they can get to,” their father reveals, pointing to a trolley that runs down the steel beam under the roof above the master loft. “You can strap yourself onto here and then push off.”

In addition to providing a place for the family to escape the city on weekends and holidays, Vite wanted to set the stage in the house for a few cherished vintage pieces he inherited from his late parents. “The interior design was all about finding a home for my father’s old furniture he had bought in the early sixties in New York. It’s all authentic midcentury-modern furniture, and I designed the interior around it.”

Sustainability as style

The LEED-accredited architect is reluctant to categorize the architectural style of his idiosyncratic house. “What they call it up here is a contemporary mountain home, because it very much has the feel of a timber frame, although it is done in steel,” he says. “But rather than talking about a style, the sustainability feature is more important to me.”

From the construction standpoint, the house is based on a standard wood module to limit material waste, which actually got Vite in trouble with one particular Minturn resident. “There is a guy up here who goes around the construction sites, picking up wood waste for his wood-burning stove at home. He would complain that we didn’t have enough wood waste and gave us a hard time.”

The carefully calculated use of exterior wood is to protect the building from driving rain in support of the actual weather barrier behind the wood. “All these gaps are open,” Vite shows. “It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.” Air exchange is critical for a highly insulated house at this altitude, where the air is extremely dry. “You are living and cooking and doing all these things that increase the humidity inside the house,” he explains. Instead of trapping the warm, very moist air inside, the house can breathe it out. Vite also installed a heat recovery air exchanger that pushes warm, inside-air to heat colder air coming in to ventilate the house, without using the heating system.

“It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.”

Vite received the 2013 Award of Citation from the American Institute of Architects for this project.

Tight house, tight Community

Being awarded such a significant professional accolade from AIA is nice, sure, but what truly warms the architect’s heart is how the locals perceive the standout structure they’ve come to call the “skinny house.” “We get compliments on it all the time. People are stopping by, saying they’ve watched it go up and want to look at the inside,” he says. “I love that the town loves the house.” △

“I love that the town loves the house.”

Sense of Place: Designed for legacy in Aspen

Mountain homes in Aspen, Colorado, are built to stay in the family for generations

Aspen is steeped in tradition. Generation after generation, families vacation at the posh resort to ski in winter and to celebrate the town's famous festivals in summer. Slope-side chalets and opulent second homes alike are built for legacy, as venues for extended family to gather and carry on traditions, season to season. A continuity that translates into architecture and decors of great depth and layering.

Nevertheless, even mountain folks for a fortnight must have functionality alongside style, beginning at the entry. “There is that sense of arrival at a mountain home,” says Sarah Broughton, co-owner of Rowland and Broughton (R+B), an architecture and interior design firm in Aspen and Denver. Aspen homes are planned with the understanding that one comes in from the elements. “People need to be able to knock snow off their boots.”

"Aspen homes are planned with the understanding that one comes in from the elements."

Style without borders

Many of R+B’s clients have primary homes on the beach or in big cities, all over the world. “One thing that is important to them is that they really feel they are in Aspen,” says Broughton, a modernist at heart. To achieve this sense of place, she relies on natural materials such as wood, grasscloth, and natural stone — “things you see when you look out the window.” What’s more, treating woods in surprising ways, such as planking or wire-brushing, brings out something special in a natural material.

Broughton complements mountain settings and modern, clean lines with cashmeres and wools in the furniture and textiles. She loves to add ample pillows and throws on beds and couches. “Hemp, wool, and cashmere textures and patterns can speak to a natural environment without being literal,” the award-winning architect says. The beauty of sunlight falling through an aspen forest’s canopies, for instance, can translate into a pattern. Twinkling lights become reminiscent of a starry winter night in the Rocky Mountains.

“Hemp, wool, and cashmere textures and patterns can speak to a natural environment without being literal.”

Black Birch Modern

With its clean-lined, minimal design, Black Birch Modern in Aspen is an example of a mountain retreat that not only boasts stunning alpine-modern architecture, but is warm and welcoming to boot. R+B achieved this balancing act by bringing outdoor materials inside. That, Broughton believes, is something anyone can do at home. “Carrying a material found around the outside of the house into the flooring, for example, is an effective way to blur that indoor-outdoor line, which is such a quintessential element of Aspen style.”

Bringing Aspen home