Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Villas in the Trees

Thailand's enchanted Keemala Resort — architecture hidden in the woodlands

Keemala Resort on Thailand's mountainous island of Phuket features four different villa styles, pods, and pool houses by Bangkok-based Space Architects, with interior design by Pisud Design Company.

Overlooking and the Andaman Sea, Keemala harnesses the history of fictitious ancient Phuket settlers and incorporates the story of four different clans within the resort. The architecture of the four different villa types reflects the skills and way of life of each of the groups. Keemala and its grounds are designed as an expansion of the surrounding landscape, making use of natural features such as mature trees, streams and waterfalls and integrating these into the overall design.

Peaceful Panopticon

Hikers throughout the American Northwest find solace in restored historical observation towers like the Park Butte fire lookout on Mount Baker

A hike to the Park Butte fire lookout on Mount Baker, Washington, tracks the forgotten history of the sparse observation towers that were once manned year round. Throughout the American Northwest, some are now restored as overnight shelters for solace seekers.

Walk-up getaway

It’s a torrid summer day. My husband, Andrew, and I are halfway up a trail in Mount Baker’s backyard in Washington. The heather flowers show signs of mortality, their normally bright, fuchsia-colored blossoms dried up into a brown, crusty shell. The open meadows are less vibrant than normal for this time of year.

The flowers came and are almost gone, signs pointing toward the end of summer. We are on a mission to spend the night in the historic Park Butte Lookout.

The hike is a steady uphill climb to the top, where we can see Mount Baker sprawling before us with emaciated pools of shallow water and red dirt staining the meadows in the foreground. The bright reds, oranges, and coppers are signs of mineral-rich soil and the fingerprints of the receded glacier on a slowly transforming landscape. We pass small groups of hikers, many with dogs, and come across a few larger Boy Scout and summer-camp parties. It seems the lookout towers fascinate young and old, serious thrill junkies, but also solace seekers.

“ It seems the lookout towers fascinate young and old, serious thrill junkies, but also solace seekers.”

Fire lookouts — a tradition of the Northwest

Two years ago, I had no idea fire lookouts even existed. After moving to Seattle, I became obsessed with them when a friend mentioned there were numerous towers across the Northwest. Built as early detection and suppression stations for forest fires, the lookouts housed fire-lookout workers, who lived in them full-time. Usually set on the highest pinnacle, with a 360-degree view of its surroundings, the lookout tower provided a prime viewing platform with sight lines as far as the eye can see. Being an architect, I was fascinated by their iconic design, beautiful in its functionality and frugality, and a new typology for me.

"Usually set on the highest pinnacle, with a 360-degree view of its surroundings, the lookout tower provided a prime viewing platform with sight lines as far as the eye can see."

Most lookouts are made of wood and must withstand very harsh climate conditions, being located so high and exposed to the elements. So I respect the simple, straightforward design engineered for easy duplication and constructability. Thick layers of paint have been applied to the wood, protecting its wear from the weather and, hopefully, extending durability. The wooden windows no longer open, since they’ve been permanently sealed to halt the snow and rain damage, but the shutters still function with some old-fashioned elbow grease. Contrasting today’s cheap construction and design gimmicks, the towers reflect an authentic practicality that I can aspire to communicate with my architecture, and they are a humbling reminder of how we should be building our homes and cities, reclaiming a simpler time, when objects and things did not rule our lives.

"They are a humbling reminder of how we should be building our homes and cities, reclaiming a simpler time where objects and things did not rule our lives."

The lookout towers in the United States were first erected after the Great Fire of 1910, which burned three million acres of forest in Washington, Montana, and Idaho. The fire resulted in more regulations and protocols from the U.S. Forest Service, implemented to prevent this tragedy from happening again. The Civil Conservation Corps (CCC) constructed towers all across the nation in the decade following the Depression. During World War II, human lookouts also served as enemy aircraft spotters, especially on the West Coast. After about 1960, more advanced technology made most of the towers obsolete. Fires were no longer fought via human observation, but instead with radios, aircraft, and finally global positioning systems (GPS) with satellite technology. As a result, the lookout towers were no longer of use, and many fell into disrepair.

Park Butte Lookout

Our Park Butte Lookout was built in 1932 and was in service until 1961. Its style is known as an L-4, a square fourteen by fourteen-foot (about 4.27 by 4.27-meter) wood cab atop heavy timber posts with a cedar-shingled gable roof and operable shutters protecting a full width of ribbon windows at each side. It was the most popular live-in lookout design and one that was replicated across the Northwest. It perches majestically on the peak of boulders, like Foucault’s perfect panopticon, watching all of nature from its roost. What’s fun about lookout hikes is that the towers come into view not long after you set out on the trail up the mountain, hinting at the reward that awaits, though there is still much elevation to be gained before reaching the summit. I look upward to seek a vantage point, stealing glimpses of the perfectly square object perched and waiting for my arrival, and I know it will be well worth the sweat.

"It perches majestically on the peak of boulders, like Foucault’s perfect panopticon, watching all of nature from its roost."

Many of these lookouts are kept in working order by local volunteer groups or organizations dedicated to preserving them. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Park Butte Lookout is maintained by the Skagit Alpine Club, a group of mountaineers who service the exterior, occasionally clean inside, and stock it with the bare necessities for emergencies—or even forgotten matches. I appreciate the remaining lookouts even more for this reason; they have that element of home to them because knowledgeable caretakers conserve their special historical and spiritual ambience. It’s an inspiration to us all to treat other people and things with just as much tender care.

Once ascended, my usual concerns are a memory: The bustling urban life I live in Seattle is far away, and I slip into nature’s meditative rhythm. There are no deadlines, only observations and reflections. There are no agendas, only submitting to the mountain’s siren song. Layers are peeled back, noise stops, nonessentials dissipate. Time becomes the passing sky, clouds, and breeze, not numbers on a clock or phone. I replenish myself with water and food not because it is noon, but because I listened to the thirst and to hunger rumbling in my stomach. The question of what to do next is replaced with almost no thoughts at all as I easily succumb to nature’s nonexistent curriculum.

“Once ascended, my usual concerns are a memory: The bustling urban life I live in Seattle is far away, and I slip into nature's meditative rhythm.”

These lookout towers are remote. However, some have cell phone reception at the top, which makes for interesting observations as we relax on the deck reading, writing, and reflecting. Hikers come up huffing and puffing because the last stretch of the trail is perhaps the hardest. The gravel trail gives way to larger boulders that require a scramble, and the climb is steeper than the average grade on most of the hike. The lookout is perched on these boulders, lifted with stubby wooden posts so it oats slightly above. After taking in the awe-inspiring view, many visitors to the lookout immediately pull out their cell phone and snap photos; a few even have selfie sticks to capture their group with the stunning mountain backdrop.

Our most pleasant encounter happens in the hottest hour of the afternoon. We had just come back from a mountain lake swim and climbed back up to the porch. It takes us a while to notice someone sitting at the shaded side of the balcony. We manage to sneak around the corner to find a man with binoculars, no cell phone or selfie stick. We begin talking, and before long we exchange contact information and look forward to meeting again. It amazes me what happens when we put our cell phones away and embrace the existence around us. Beautiful and inspiring moments are always presented to us. Will we stop and pay attention or move too fast and miss them? Perched on a fire lookout, you see more than the view. △

Oh La La, Très Chic: Chalet Les Gentianes

A very private ski-in/ski-out chalet in the French Alps

Courchevel / Saint-Bon-Tarentaise / France Les Gentianes is truly a ski-in/ski-out chalet amid a winter wonderland in the French Alps. The chalet is located right on Courchevel’s Bellecôte piste in the prestigious and quiet Residence de Bellecôte. The splendid vacation rental with seven bedrooms and seven bathrooms is one of three exclusive chalets at this residence. The catered chalet has a swimming pool, Jacuzzi, massage room, and gym.

The centre of Courchevel is a less than five minute’s walk away.

Retreat and Return

An essay on escaping to anywhere but here, getting messy in nature, and connecting to what is real

If you stand in the middle of an empty Downing Street, around 30th Avenue, in Denver and look straight ahead, you will see a light-rail station jettisoned beside the street and some low level buildings that litter the periphery as a long stretch of asphalt leads the eye to the horizon. Miles away, two grayish, 1980s skyscrapers frame a view of the foothills. You can make out the patches of snow and tree lines along the ridge and grasp for them. This glimpse of the mountains through the frame of the city, surrounded by civilization and commodity, creates the desire to run from the banal into the still, quiet reserves of solitude. Civilization and solitude, city and wilderness, the balance and distinctions can often be so tenuous and vague. Where does one start and one begin?

Filter of escape

When I think of escape, it’s about an ethereal atmosphere: where the light sending shafts across your face is just right, words fall with a satisfying poignancy; it’s very poetic and meaningful. It is the sort of moment where you imagine that you could probably write a play, or a memoir. It is often meticulously calculated and captured on social media. It’s this dream I sometimes have: his face clear amongst a hazy backdrop, and there is a golden glowing that moves warmly across his lips as they move. It is late summertime. I do not know what he is saying, but I feel the meaning of the words. There is a way that our photographs make things much softer, much more beautiful, much more inhabitable than they really are.

“It is the sort of moment where you imagine that you could probably write a play, or a memoir.”

How do we value the observing and interacting within landscapes without resulting in the dreamy nostalgia of escapism? What is the danger of over-romanticizing our nature, our hideaways?

Historically, “escape” denoted fleeing towards liberty, freed from an irksome or controlling reality. It was only in the 1930s that escape began to be used etymologically as a method for retreating from reality. To “escape” became “escapism”: the tendency to seek distraction and relief from unpleasant realities, especially by seeking entertainment or engaging in fantasy, modeled by escapist literature that provided a refuge for those harried by the changes in modernism.

Similarly, in the 1800s, the noun “hideaway” denoted a person running away or a fugitive but shifted in the 1900s to primarily be used to describe a place of concealment or retreat.

Modern escapism

Research on “escapism” began in the 40s and 50s, a post-war mentality in which escape was a necessity, and researchers examined the connections between media consumption and life satisfaction. In 1996, Peter Vorderer described escapism as the desire most people have, in unsatisfying circumstances, to flee reality in a cognitive, physical, or emotional way.

Geographer-cum-philosopher Yi-Fu Tuan’s book Escapism is a dazzling exploration on cultural manifestations of this desire. In Neolithic times, our ancestors may have built shelters and plated crops to escape nature’s harshness, but now we escape the urban for the suburban lawns and parks. Tuan speaks of Disneyland, glass-towers, ivory towers, and malls—all tenuous monuments to the dream, away from the uncertainties of life, often imposed by a nature we still cannot yet control. At what point, Tuan argues, is escape inescapable? How is escapism hardwired into our human makeup? If to escape reality is to create a malleable nature, then what aspect of culture is not escape?

“If to escape reality is to create a malleable nature, then what aspect of culture is not escape?”

Away, away

“The grass is greener on the other side,” runs the clichéd motto. I often search for discounted plane tickets the night before a large deadline or after a particularly nasty fight. I could move somewhere else; I could start over. I would not need to worry about these things if I ran. A sudden urge to sprint until I’m panting, until all the air has dispelled from my chest, to use my body, overcomes me. It reminds me of an Avett Brothers refrain:

The weight of lies will bring you down And follow you to every town 'cause Nothing happens here that doesn't happen there So, when you run make sure you run To something and not away from 'cause Lies don't need an aeroplane to chase you anywhere

Plainly, People want to “get away,” and I fully understand the desire. Ecotourism has exploded. We put rails along the edges of cliffs and commercialize Yosemite, all the while promoting an Airbnb in the middle of nowhere. Advertisements show us quiet beaches, toes in the sand, and shimmering waters devoid of noise and other tourists. We would be much better people, we are sure, if it were not for the distractions. A friend once told me, “Iceland is the one place on earth that looks the least like earth.” Beautiful, stark waterfalls and geysers against a backdrop of light yellows and green, an unearthly landscape, an utterly foreign nature. A place that seems to scream clarity from its minimalist landscapes. We escape to a place least like Earth; we want to stay there and soak in this alien feeling forever. We want to easily escape to places that are difficult to reach.

The desire to escape to simple and easy landscapes stems from a “milk and honey” mentality of the Promised Land that came to fruition in the literary genre of the pastoral. We’ve all heard the lines in our high school English courses from Marvell:

“Come lay with me and be my love and we will all the pleasures prove.”

Pastoral paradise

Scholars have condemned the pastoral for its flights of fancy and its tendency to oversimplify complex societal situations for a romanticized and reductionist nature. A genre predicated upon escapism, the pastoral offered a comfortable landscape to run to when society grew too weary or complex. Centered upon the notion of “Arcadia,” there was a landscape and realm of nature that remained untouched, primitive, and pure from the ravages of civilization where utopian harmony and balance reigned supreme. The shepherd sang of a “Garden,” a lost Edenic form of existence in nature. Raymond Williams, a key pastoral critic, argued that the pastoral rests upon the notion that the industrialized city has removed us from the peaceful existence we once had in the country. For him, this is “myth functioning as memory,” remembering a false past that our ideals have created, where the present looks back toward a decline of simple life in the past. We have all heard it, thought it, felt it: “Life was so much simpler back then.”

We want to escape back to the simple, when we were carefree and life had no troubles. When all we had to do during the day was watch a river lazily float by us. My friend and I plan trips to Moab, plan trips to Zion, plan trips to Yosemite. We think of the tiny homes we could purchase, the vans we could remodel, and slowly tweak our plans to escape from the grid.

“We think of the tiny homes we could purchase, the vans we could remodel, and slowly tweak our plans to escape from the grid.”

Which world is blasé?

At its core, escapism hinges on the question of the “real.” What is reality and what is fantasy? The critics tell us to blur the lines and mix them up; virtual reality asserts that these questions are passé.

But, rather, might they be blasé? Blasé came into linguistic fashion 1913 to denote when the ability to tell the distinction between particular things is lost. A haziness of atmosphere descends and mixes it all up. I often find that my escapist fantasies are dreamy: edges are blurry and details are vague, what I am reaching for isn’t concrete but an atmosphere, a feeling, that my memory has recreated for me. I am always confusing myself with my real life and the life I live in my head, the lives I could live and the person that I could be. It is easy to escape to the mind space where I have it all together; where I am writing my next work from the porch of my secluded mountain cabin.

“It is easy to escape to the mind space where I have it all together; where I am writing my next work from the porch of my secluded mountain cabin.”

Experiencing within context

When scientists speak of one’s ability to perceive, they talk about “enframing.” As we view a site or landscape, we are compelled to frame and categorize it. Our site defines our reality—we may know that other things exist because we have seen them before, but, at every moment, we are only capable of perceiving and understanding what the widths of our eyes allow us. Yi-Fu Tuan argues that modern men and women, living amongst aspiration and pretension, suffer from Milan Kundera’s “unbearable lightness of being.” Life up so high doesn’t seem so real. We want something material, something to come into contact with.

“Life up so high doesn’t seem so real.”

For Tuan, the “real” is the impact, sensation, and felt pressure of nature: callouses on feet at the end of a long, arduous hike; sweat lining our brows; dirt under our finger nails. The real exerts a feeling of “aliveness,” where habits are shaken up. It’s to come close to the ground. The Greek origin of the word humiliation stems from hummus and in its literal terminology meant “to come close to the earth,” mirroring the story of Anteaus, a Herculean type man whose strength only persisted as long as he was touching the ground. Bring Anteaus to the heights and he was helpless.

If, as Tuan argues, human restlessness looks for relief in geographical mobility, our desire to move closer to nature is a natural one. We search to escape to a place of lucidity that comes from simplification. For Tuan, if an experience brings clarity rather than just simplification, one can arguably say that they have encountered the real. This is the difference between appreciating moments, atmospheres, and landscapes, and escaping from the pressures to a “blank page.” What one needs is not escapism, but rather a middle landscape that stays in touch with the raw reality of the natural world that remembers the connection to civilization as well. False divides have never helped us. When we retreat to nature, we are never going to blank spaces, but places with a palpable, experiential essence—ecosystems with existence long before we imposed our imagination upon theses places.

What moves escapism toward the notion of retreat and return? Action, honest encounters with nature. Escapism rarely translates into action. It is usually a state of mind we hide in. Retreat, however, requires movement and action, relying on a balance between wilderness and civilization. When we only dream of escapism or see landscapes like National Parks as the locale of our get-aways, we create an abstraction that makes it easy to exploit other landscapes.

“Retreat, however, requires movement and action, relying on a balance between wilderness and civilization.”

Return with clarification

Thoreau may have secluded himself to retreat to Walden, but he returned with an answer, a prophecy for a complex and frazzled society, teetering on the uncertain brink of industrialism. George Puttenham, one of the first pastoral theorists, did not see the form as merely recording the escape to a more rustic form of life, but as a serious guise for societal discourse. It had a didactic duty to return with clarification for modern life. It was about bringing back balance between the wild and the human.

What we need is a return to dirt, to the messy physicality of nature experiences. Not the coziness that we seek to escape to, but places of deep meaning that we return to for the quiet balance we desire. As William Cronnon argues about wilderness theory: If we imagine that our true “home” is a wilderness we can escape to, we often forgive ourselves for exploiting the land that we actually live on. Instead, a quality of “wildness” might be instilled in all the landscapes we inhabit, not just the sublime we want to run away to. Escapism, in this way, can be a dangerous nostalgia: despising the real in favor for the imagined. Escapism operates off a dissatisfaction and false dualism that can actually subtly encourage environmental exploitation: instead of seeing nature, wildness, as something that continually surrounds us, we escape to “wild” places, while leaving the urban to continue to die. We forget to gently tend our gardens, when the goal of our relationship with landscape is the task of making a fulfilling home within it.

“What we need is a return to dirt, to the messy physicality of nature experiences.”

“If we imagine that our true ‘home’ is a wilderness we can escape to, we often forgive ourselves for exploiting the land that we actually live on.”

It’s the difference between a dreamy pasture and the dirt. In the dirt, there is a beauty that has forgiven its sense of idealism. It is not about the ease, though this can be a benefit. While the reconstruction of the event can be nostalgic, often the journey in the wilderness is not: one sweats, scrapes their knees, huddles under a tree from a thunderstorm, or comes into contact with an animal much larger and more powerful. What we reclaim in a retreat and return is real action and the sense of our bodies—the sense of touch, of reconnecting with the environs that surround us. The retreat into nature can remind us to be consciously aware that we are not separate from nature but a part of and subject to it. We are wrapped up, intertwined within it—where then can we escape from ourselves?

“In the dirt, there is a beauty that has forgiven its sense of idealism.”

Wilderness therapy

There are countless organizations today that rely on this sort of wilderness therapy—bringing people out into nature as an opportunity to disconnect from the virtual and remember the real. While not all of us are ready to live in a van or fend for ourselves in the wild, retreating and returning gives us the pros of a connection with landscape without falling back onto distraction, selfishness, and a misconstruction of nature. Retreating away for solace, meditation, and a clean slate, remembering the environment and mountains that sustain us, and returning to tend for others in a harried society is the beauty of the soil.

In Norway, Arne Naess, the father of the Deep Ecology movement, pioneered the “Friluftsliv” movement—a conviction that an outdoor life can provide an antidote to the stresses of urban conditions. It’s not about an either/or but a both/and. A hideaway, a landscape, an escape that connects you to the “real” can never be escapism. It is an experience that connects you to materiality, a grounding that comes closer to the earth, an eye that recognizes beauty in the particular.

So here’s to the weekend warrior, the backcountry skier, the Chautauqua walker, and the Rocky Mountain National Park junky. Here’s to the gardener, the climber-conservationist, and the trail runner. Here’s to the people who aren’t afraid to shove their hands in the dirt, who aren’t desperate for a chance to run away but longing for a connection to the still, quiet moments of reality. Here’s to the mountains that are always beckoning us to come closer, get humiliated, and find contentment. △

Dirt

Antaeus reveled in the materiality

of his strength

which became humiliation

like its root hummus

like to come close

to the level of the ridge

and feel the terra.

To know that aspens

are rhizomes,

interconnected,

roots woven through soil,

nothing left out.

To hideaway from

the dirt is to

drift toward the sun,

risking a heavy pitch

downward, mutually assured destruction.

I am trying to get close to the reality of taxonomy,

the soil, the naming, the root.

Here is best I can say,

far from despair:

From dirt we came

and dirt we shall return.

Poem by Haley Littleton / Illustration by Ben O'Brien

The Nomad Behind the Lens

A conversation with photographer Garrett King, @shortstache on Instagram

Garrett King, a Colorado transplant from Texas, goes by the moniker “@shortstache” on Instagram. The name originates from a company he and a friend started after college, and while the company is no longer a part of King’s life, the tongue-in-cheek name remains and leads 119,000 followers to King’s photography.

King, more comfortable with anonymity than self-promotion or marketing, worked his way from a “weekend warrior” to a full-time photographer and shares his thoughts on the longevity of the field, as well as the community he’s creating through his work in collaboration with others. King’s work emphasizes perspective and playfulness of natural landscapes, while not sacrificing composition and contrast.

A conversation with Garrett King

What got you into photography?

I was born in Amarillo, Texas, and studied design and fine arts at Texas Tech and West Texas A&M. I mainly focused on videography, though, not photography. My friend and I started a company called “Shortstache” where we made short films about people in Texas who inspired us, like the oldest letter-presser in the state and a woman who made bicycles out of recycled materials.

Hence the name: @shortstache?

Right. At the time, we were competing in a mustache-growing contest, and it kind of stuck. Now it’s just me.

And then Instagram came along…

I joined Instagram about two years ago and never had the intention of using it as a platform to turn my photography into my career. I never intended to “make a name” for myself on Instagram. I would just respond back to everyone. They would respond; I would respond. It just kept going.

So it became a platform for community for you?

Exactly. I’ve met some of my best friends in the world through Instagram because we connected over a common goal or interest. I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram. It’s great because you can ask a question about a new place and get feedback almost immediately. Once, a few friends and I went to Portland, Oregon, and I posted that we didn’t have a car but would love to go around the city. Quickly, I got a message from a guy saying that he could be there in an hour, and I’ve been close friends with him ever since.

"I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram."

Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier. I’ve found a mutual respect pervades the community, and it’s been fun to see that come into fruition in my life and work.

"Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier."

How did you find yourself transitioning from videography and design to photography?

I’ve spent most of my working life designing. Photography was always an offshoot, a side hobby. It was interesting how things shifted: When I moved to Colorado two years ago, I quickly became a weekend warrior. I was leaving work at 5 p.m. on a Friday, driving until 2 a.m., camping and exploring and shooting wherever I could. I started posting my photos from these trips on Instagram, and, I guess, it sparked people’s interest.

Why camping and natural spaces in particular and not classic city shots or portraits?

I could only do the city thing for so long. You can get nightlife and restaurants in a lot of places, but, when I moved to Colorado, the mountains were in my backyard, and there was just so much to see and do. I found myself always escaping to the mountains to build stories or create memories. I will say, though, some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work.

"Some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work."

What has your focus been in developing your work?

For me, it’s always been about storytelling. You could consider me an adventure photographer, but the goal is always about capturing a moment. I want to continually get to the bare essentials and strip things down to the core. When I look at the bigger picture, I hope my work is inspiring and propelling me to see more and do more, while growing as a person. It is an extension of myself, after all. As it gets better, I want to get better. People are always asking me about what gear I use but it’s not really about gear; it’s about a developed style and whether you’re producing consistent and engaging work. I think you have to have the eyes and passion to discover good shots and you have to practice, practice, practice.

"It’s always been about storytelling."

Now that you’re a full time photographer, there must be a necessary separation between Instagram and work for you…

There definitely has to be. Anyone who asks me about their photography and how to make it big on the platform, I try to remind them that it’s a launching pad and business tool. I’ve had companies see my work through Instagram and invite me to shoot for them. It always goes back to the work. Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity. If you’re good and passionate, people will find you.

"Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity."

Any current projects?

Something I’ve been really excited about is a collaborative effort with other photographers I know, called @collectivenomads. We wanted to take creative people in different mediums and build each other up.

What do you want people to think when they stumble across your photography?

I hope they ultimately see that I’m a real person. Yeah, I want to have a consistent and built-up style, but I want people to see who I am, as a person who does the same stuff as them, and engage.

I never want my work to be dependent on a platform. I’m all about being on Instagram for the right reason: to know people and build relationships. It was never about free gear or “blowing up.” The dream was always to make my lifestyle I love into a paid job. I love design and want to continue to do that while also exploring my work as a photographer. △

Over the Edge

French filmmaker Sébastien Montaz-Rosset goes to vertiginous hights to tell extreme athletes' heart-stopping adventure stories

French filmmaker Sébastien Montaz-Rosset dangles off cliffs and races across mountaintops to capture his swashbuckling subjects’ daring stunts but also to convey an intimate look at their fears, failures, and triumphs.

Watching the spellbinding work of French filmmaker Sébastien Montaz-Rosset, you want to cover your eyes but can’t look away all the same. The majestic mountaintop views immediately draw you in. But what mercilessly demands your soul and every fiber of your body is the heart-pounding terror that comes from witnessing death-taunting stunts; his subjects flirt with doom at every turn. This action-adventure-extreme-sports filmmaker captures shots from breathtaking angles most other filmmakers would never even dream of—say, dangling off a cliff or running along steep alpine ridges at full tilt. An athlete himself, Montaz-Rosset climbs—alongside his daredevil subjects—to virtually inaccessible locations thought to be beyond the realms of possibility.

High skill

That Montaz-Rosset is a passionate mountaineer, rock climber, runner, and skier goes along with the territory. It takes a high level of outdoor expertise and mountaineering skills coupled with innovative equipment to allow him to accompany people on their enthralling journeys. His work has been steadily gaining worldwide attention, most notably in the category of highlining, a combination of rock climbing, slacklining, and tightrope walking at treacherous heights, such as between two skyscrapers or mountain peaks. To slackliners, this is the pinnacle of the sport and something that’s attempted only after years of experience. Any small shift in weight or wind can easily send the cord into trampoline-like motion. Swift falls happen often, and while some use a fall leash to tether them to the main line, others pack only a small parachute as protection. The filmmaker and his athletes can’t plan ahead too much as the troupe pioneers this new evolution of the sport. Montaz-Rosset’s work requires quick thinking, improvising, and a remarkable amount of knowledge and training in wilderness safety.

The mountain guide turned adventure filmmaker got his start shooting clients during mountain excursions in France. “I was born in Les Arcs in the French Alps and have always lived in the mountains. Skiing and climbing was what we all did growing up, and I became a mountain guide and ski instructor, like a lot of people who grow up in these areas,” says Montaz-Rosset.

Telling stories of triumph, fear, and failure

In addition to shooting commercials, Montaz-Rosset also recently filmed the first-ever attempt at suspending a highline between two hot-air balloons high above the Pyrenees. He strives to tell extraordinary stories about real people performing acts that trigger an avalanche of emotions in the athletes and their spectators. His work is aesthetically breathtaking, but it runs much deeper than thrilling action shots. It’s about letting the viewer behind the curtain to see the laughter, fear, triumphs, and failures. It’s about finding the strength to pursue aspirations. The filmmaker’s trick is to show the athletes’ point of view—the passion—so the viewer has an emotional connection while watching their gut-wrenching maneuvers; and sheer, raw vivaciousness bleeds into every frame of his films.

While high anxiety is a natural element of any extreme sport, Montaz-Rosset’s films show how the athletes react to and embrace it. “The people I film are so expert at what they do, fear isn’t really a big factor. It’s always present, but it helps you to concentrate on what you’re doing...it brings focus.”

“The people I film are so expert at what they do, fear isn’t really a big factor. It’s always present, but it helps you to concentrate on what you’re doing...it brings focus.”

The twist is that the athletes themselves don’t know if their stunt will be successful or not. The films are about the attempt and all the internal and external obstacles that go along with the journey. “I love telling stories, and I get inspired wherever there’s an interesting and different story to tell. It doesn’t have to be adventure sports, but that’s the environment I’ve grown up and live in, so the stories I tell are about the people in this environment,” he says.

The Flying Frenchies

So who are the subjects who fuel this high-octane artwork? Enter The Flying Frenchies, a wild and gregarious bunch of twenty or so lively, flamboyant characters. All are entertainers in their own right; each is equipped with her or his own skill and zeal. Performance art marries adventure sport in Montaz-Rosset’s film The Flying Frenchies: Back to the Fjords, where this gang of extreme athletes and performers bands together to create an outdoor alpine extravaganza like no other.

“These guys are always thinking up new ideas for stunts and things to push themselves in what they do. Several of them are circus performers, or they’re climbers and mountaineers, essentially. So what I’ve filmed is just a small part of what they do.”

Engineers, along with BASE jumpers, wingsuiters, and musicians, make up the colorful pack. In Montaz-Rosset’s film, he follows the group as they travel through the fjords of Norway on a monthlong trip, embarking on various new extreme-sport-style adventures. Although at first glance it all feels very whimsical and impulsive—perhaps because they intermittently don clown costumes and props—months of painstaking preparation have gone into planning the journey, including intricate mathematical calculations and rigorous testing phases.

The Flying Frenchies travel across the country in a vintage red circus bus that has been renovated and packed to the gills with enough food for roughly a month. They also strongly value leaving zero waste as they go along, which takes additional planning. At night, the crew sleeps in tents, battling wind and rain and sometimes unexpectedly harsh elements. Montaz-Rosset captures outbursts of laughter and impromptu dancing, juxtaposing those scenes against hushed moments of stomach-knotting stunts in progress. On one rough night, gusting winds hurled a tent filled with camera equipment off the top of the mountain. “It was more of a setback timewise...we lost some things, but there was enough gear to be able to replace what was lost,” he says.

Artistry and athleticism

The worlds of performance and mountain sports collide when filming visually stunning footage of athletes running and cartwheeling off the mountain’s edge before parachuting down into the valley. Beautifully blending artistry and athleticism, the film embodies—and embraces—doing the impossible. Clowns and acrobats climb peaks; other performers BASE jump off slacklines. It’s about watching people push themselves to the brink of their physical and mental abilities—to witness what unleashes a landslide of emotion from within their souls and sets their spirits free—that we feel an incredible, intangible connection to them. “I just let them do their thing and try and be as unobtrusive as possible. You never know what you’re going to get filming them, so it’s always fun,” says Montaz-Rosset.

The summit of the adventure in Back to the Fjords occurs when The Flying Frenchies assemble and test an enormous human catapult they’ve dreamed up and meticulously engineered to launch each other off the mountain. It’s carried piece by piece up to the peak and assembled near the edge, a colossal experiment. The vision was to shoot performers skyward—all the while hoping they wouldn’t pass out from bearing up against 10 Gs—so they’d still be able to safely deploy their parachutes to float down to the valley below.

The filmmaker says, “Most of the people I film are people I know as friends, or have gotten to know from working and living in the mountains. The extreme sports are what they do, but it isn’t who they are...so filming the sports is a way of telling their stories. And, of course, these sports have a big visual impact.” There is intimacy in watching someone embark on the unknown. The viewer feels the sensation of being set free along with the performer and can experience, in tandem, a refreshing jolt of the liberation that comes from propelling at breakneck speed through the air, arms and legs flailing about.

“The extreme sports are what they do, but it isn’t who they are...so filming the sports is a way of telling their stories.”

Seeing The Frenchies feed off and inspire one another, their sense of camaraderie and friendship is palpable. Montaz-Rosset shows how these friends test the boundaries of their bodies and their relationships. The filmmaker and his subjects together push the confines of their sport and their personal lives. Pioneers in adventure-filmmaking and new sports, they transform viewers by manifesting that the impossible is possible. △

In Memoriam Tancrède Melet

With the heaviest of hearts, we are sharing with you that shortly after this story was written, we learned Flying Frenchie Tancrède Melet died while preparing for a hot-air balloon stunt in Drôme, France, in January. The 32-year-old expert slackliner, BASE jumper, and wingsuiter accidentally fell approximately 100 feet (ca. 30 meters) when the bal- loon abruptly sprang off the ground. Melet leaves behind a life companion and a young daughter. His death is a stark reminder of how all too fragile life truly is and that no matter how trained we are, how meticulous, how dynamic, how invaluable to others—the unthinkable still happens.

Concrete Perspectives

Australian photographer Jake Weisz discovers the minimalist Amangiri Resort in Southern Utah

Through his lense and all his senses, Australian photographer Jake Weisz (@jakeling) experiences the calm luxe and the raw surrounding nature of Southern Utah’s Amangiri Resort, where minimalist architecture in monochromatic concrete lies below the buttes and mesas of Canyon Point.

After an unforgettable, slow drive along a private, paved road between colossal ridges and across vast landscapes, we arrived at what I can only describe as a concrete castle hiding in the rocks of Southern Utah. Amangiri was and remains the greatest architectural experience of my life as a photographer. Minimalism, texture, silhouette... all unassuming until I wandered through this artistic haven of concrete walls.

A collaborative design by architects Rick Joy (Tucson, Arizona), Marwan Al-Sayed (Hollywood, California) and Wendell Burnette (Phoenix, Arizona), Amangiri spreads over 600 acres (243 hectares), with 34 suites and a four-bedroom mesa home, a lounge, several swimming pools, spa, fitness center and a central pavilion that includes a library, art gallery, and both private and public dining areas. The architects were commissioned by legendary hotelier Adrian Zecha, whose Aman Resorts have redefined luxury travel in epic proportions.

Arriving at the resort

We wandered across the dramatic entrance, past the protruding canyon on the right and stepped into the first breezeway, one of numerous voluminous concrete corridors that connect each pavilion to the next, framing the valleys in the distance and creating different moments of awe every time you step inside. Throughout the day, the sun hits each breezeway at different angles, giving light and shadow new meaning, in a continuous cycle from dawn until dusk. Impressions of grandeur aside, with each stride deeper into these grand hallways, I felt closer to sublime serenity; this indescribable feeling of peace.

We were shown to our room, a one-bedroom suite on the edge of the property, backing to what at first glance reminded me of a set built for a spaghetti Western: rolling tumbleweeds, the squeaks of desert mice, expeditious hares scurrying about, the scene set against luminous canyons and a distant view of Broken Arrow Cave, an indigenous, spiritual sanctuary. Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.

“Certainly the right place for a creative’s maniacal mind to softly seep into a slumber.”

Exploring perspectives

After some rest in our noble lodgings, the photographer in me yearned to roam the grounds, Canon in hand, and to capture the tranquil austerity surrounding us. Being here, each of the architects’ decisions made sense. Moments of monotony broken by jagged slices of deep, sweeping pastel views. The polished concrete’s organic texture caressed by soft waterfalls cascading down the walls. Brief Edenic allusions in fruitful apple trees, ripe for the picking. To grasp we were only a couple hours’ drive from Las Vegas, Nevada, was almost impossible.

Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls. Rather than being clinical or cold, as unknowing observers might reckon from afar, the stark concrete structure’s monochromatic elegance creates harmonious balance between the arid landscape in a desolate summer climate and shadowed walkways affording gentle breezes of desert wind.

“Perspective became an intriguing exploration. The architecture condenses expansive canyons into splinters of light and landscape between these grand, polished concrete walls.”

Fortress of luxe

Stepping inside Amangiri superseded any notions I had of comfort and luxe. The main pavilion is a multipurpose common area scented by burning fresh sage and sunburned grain. On the walls, copious Ulrike Arnold artworks implement abstraction from the concrete’s silky texture. The interior seamlessly merges textures as if designed by rhythmic dictation. Soft leathers and animal hides, smooth oak and cement surfaces all amalgamate with the rough, rambling terrain that surrounds the resort.

I experienced color in this place like never before—the perfectly blended gradient changes from earth tones to milky hues. The architects of Amangiri also designed all interior features; furnishings, lighting, signage… all the elements reflect the Southwestern landscape and culture with subtle, emblematic references to the Native American tribes that once inhabited Canyon Point.

Dining at dusk

The Amangiri invited us to take our first meal alfresco in the Desert Lounge, a rather humbling setting for our dinner at dusk. Sitting across from my friend, charging our glasses of wine and looking out at the immense horizon, overcome with divine silence and calm, we couldn’t speak but simply look and listen. Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food. Amangiri presents a rather auspicious combination of locally sourced, farm-fresh produce and materials with modern interpretations of Southwestern traditions. Plate for plate, the decadent courses filled us, until we turned in for the night. First day, well spent.

“Within this celestial space, I discovered an understated romance in the combination of architecture, nature, and food.”

An early adventure

From the crack of dawn, Amangiri had been already awake and buzzing. We were informed to wear shoes suitable for an adventure and were later met by a car. Amangiri sits among some of the continent’s most grandiose, well-protected natural phenomena, and we were booked to experience one the resort is very proud to have on its land. At the foot of the largest of the canyons, they put us in climbing harnesses before we set off on a Via Ferrata, Italian for “Iron road.” This modern style of climbing journey involved steel cables and staples already in place for a more protected climb. The concept is to give inexperienced climbers the ability to enjoy rather dramatic and difficult peaks. And now, with my feet firmly back on the ground, I can say, the peak was indeed spectacular. Nerves aside, climbing to the top allowed me to truly experience the vastness of this beautiful place and the fragility of this natural ecosystem. I do, however, recommend taking an extra few breaths before crossing Amangiri’s signature suspension bridge between two peaks. Walking across with my camera was a rather nerve-racking experience.

After that intense climb and exploring more of the resort’s outdoor adventures, the best decision was to spend our afternoon at the Amangiri Spa. The minimalist design of this serene adults-only oasis manifested the very concepts of relief. Instead of receiving a massage treatment, I spent most of my time self-reflecting in the floating cave’s Persian salt pool. 30 minutes of pure and simple bliss, resting on the surface of tepid water, scored by meditation melodies has become my new idea of elegant content.

Departing to return

Our departure was suitingly emblematic of our entire experience at Amangiri. As we unhurriedly drove past the minimalist concrete marvel, through the resort’s expansive acreage and past a private plane landing nearby, I began to appreciate the sheer magnitude of my weeklong stay here. The space has inspired a newfound understanding of lines and light, and a greater comprehension of the relationship between nature and man-made creations. As I left, I already longed to return. △

Dwell × Alpine Modern

We are incredibly excited to announce our partnership with Dwell

From the very beginning, as we imagined Alpine Modern to be a publication about modern architecture, design and elevated living in the mountains around the world, telling people about our vision has usually included something like "You know, like if Dwell and Cereal magazine had a lovechild in the mountains..." Dwell's authority in showcasing international modern architecture and design has inspired us in our own work. This is why we are incredibly proud to announce that today marks the beginning of our partnership with Dwell.

This means, you will see some of our editorial stories on the new (launched today!) Dwell.com, published under the banner of Alpine Modern. What's more, we will present Alpine Modern "Curations" — a new element of the redesigned Dwell.com. This can be anything from a product roundup from the Alpine Modern Shop to a themed collection of stories about cabins, art and journeys in Norway.

In return, you will read cherry-picked Dwell content on Alpine Modern Editorial.

Follow @alpine_modern along on Dwell.com as Dwell and Alpine Modern together kindle a longing for elevated living, through slow storytelling, amazing photography and tightly curated alpine-modern objects. △

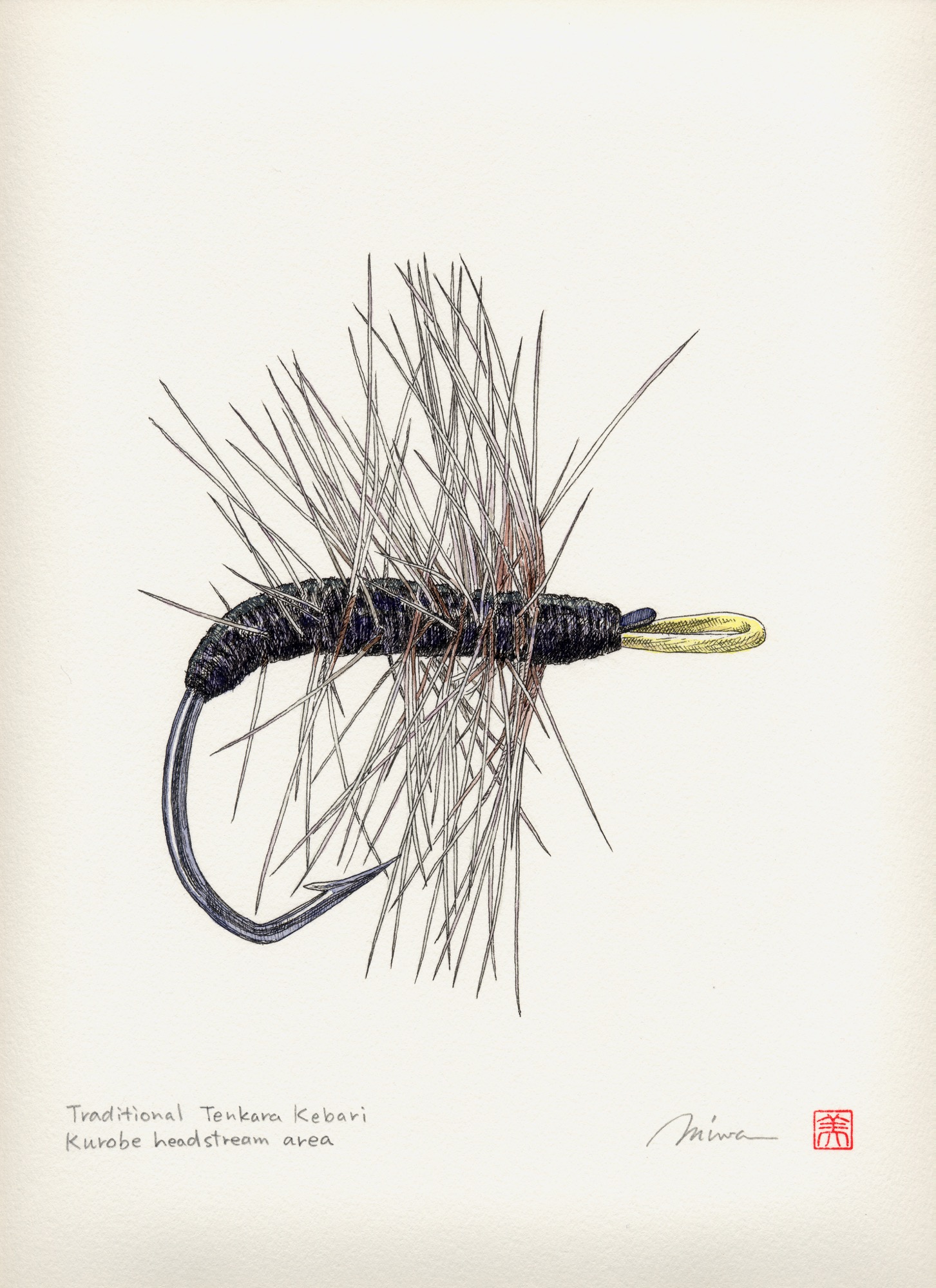

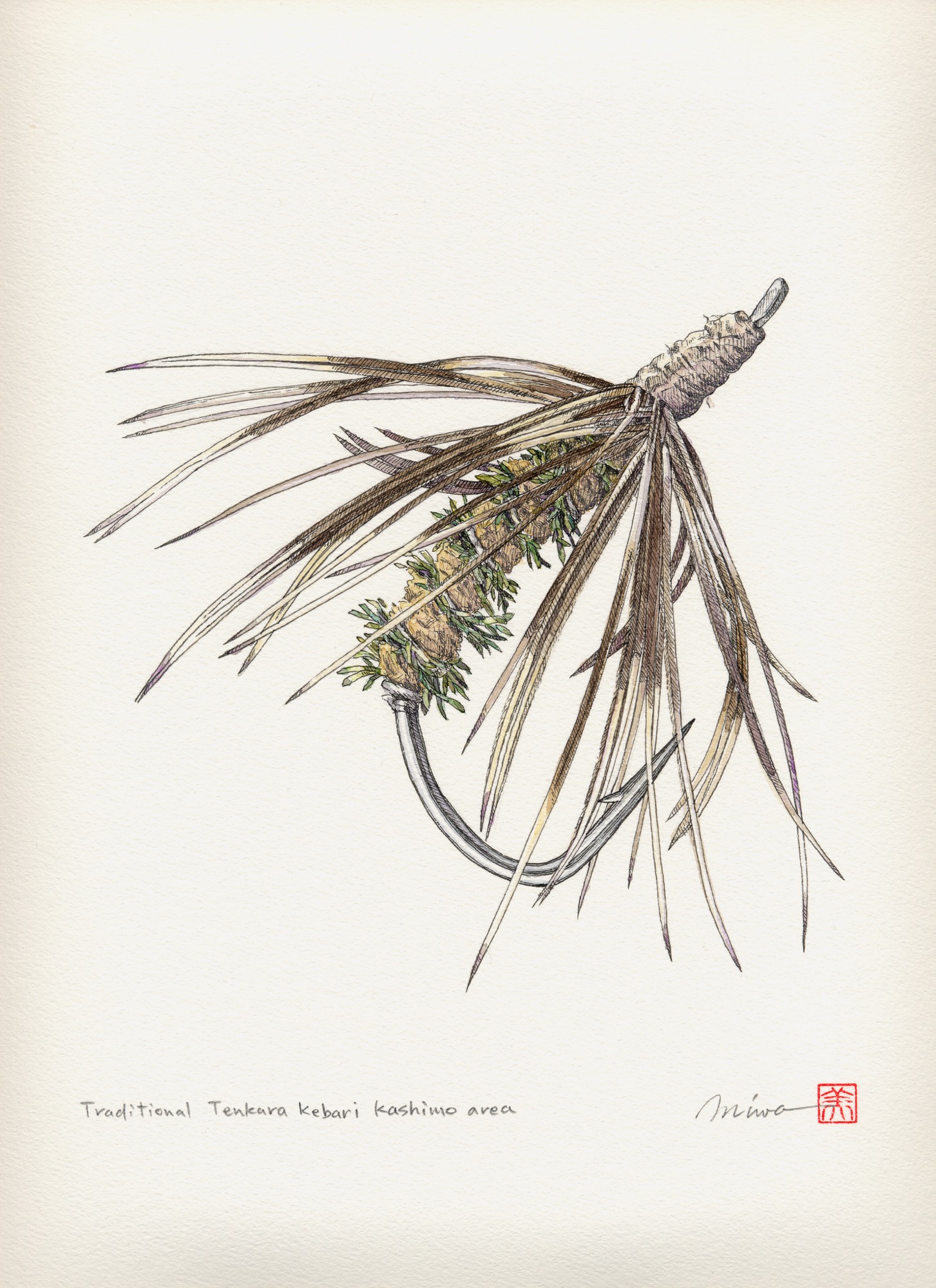

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel

Upon returning from Japan, my mind was filled with the mountain culture of tenkara, a traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. I had to share my discovery with the people at home. My next journey was founding Tenkara USA.

Clinging to mossy rock with half my body under a waterfall, I watched the torrent crash into a small basin fifty feet below, sending mist into the air and soaking my companions. Mr. Futamura observed apprehensively. Next to him, Mr. Kumazaki preferred to stare at the pool in front of him for any signs of iwana, the wild char found in the mountains of Japan. A fishing rod, small box of flies, and spools of line and tippet were stowed away in my backpack. No reel required.

As tends to happen with shing, we lost track of time somewhere along the way and now faced the crux of the trip. It was seven o’clock in the evening and would soon turn dark inside this lush forest. After a full day of rappelling, swimming through pools in impassable canyons, climbing rocks and waterfalls, and, of course, shing, we were all tired. The route ahead looked straightforward and within my comfort zone, the only caveat being a very wet climb.

My task was to climb to the top, set up an anchor, and belay my partners up. Twenty feet from the top, features on the rock face disappeared on the drier left side and forced me closer to the waterfall, where thick moss oozed like a wet sponge. I was long past the point of no return. I pushed past the fear and focused: hands and feet, hands and feet, hands and feet. The banter between Futamura and Kumazaki suddenly stopped. All sounds, including the roaring of the waterfall, seemed to vanish.

Getting there

My trip to Japan was a journey of discovery. For two months, I stayed in a small mountain village, learning everything I could about the one thing prompting my journey: tenkara.

In reality, I already knew a lot about tenkara. Three years earlier, on my first trip to Japan, I introduced myself to this traditional Japanese method of fly-fishing that uses only a long rod, line, and fly—no reel. After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love. I imagined how great it would be for backpacking and introducing people to fly- fishing in a simple, fun way. There were just so many possibilities.

"After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love."

With little information and no gear available stateside, I took on the task of introducing tenkara to the United States. Over several long months, I created Tenkara USA and since 2009 have been introducing tenkara to anglers outside of Japan. However, despite the knowledge I gained in the last three years, particularly under the tutelage of Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, Japan’s leading authority on tenkara, I knew there was much more. Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers.

"Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers."

History of tenkara

Just as the practice of metalworking appeared independently in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East and among the Incas in South America, evidence suggests that fly-fishing emerged in Europe and Japan independently of one another. Tenkara is similar to the original mechanics of fly-fishing practiced by the likes of Dame Juliana Berners and Charles Cotton, the best-known historical practitioners of fly-fishing in the West. Anglers have practiced similar fixed-line methods in many other parts of Europe, including Spain, France, Italy, and Poland. Yet, unlike the original Western fly-fishing methods, tenkara still lives in Japan.

One main distinction separating tenkara from Western fly-fishing is its origin—tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes. While the West went to work designing fly patterns, weights, strike indicators, and other gadgets to control the reach of a fly or make the activity “easier,” the typical tenkara fishermen of today adhere to the original practitioners’ thrift and reliance on skill. At the risk of seeming irrational to a Western fly angler, most tenkara anglers rely on only one fly pattern, no matter where they fish or what is hatching. As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice.

"Tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes."

"As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice."

Ancient and mysterious origins

Tenkara felt like my own personal Machu Picchu. Here was a rich but hidden mountain culture relatively unknown to the West, so unpublicized that the coastal Japanese themselves only became more aware of it in the second half of the twentieth century. Although researchers can find numerous Western fly-fishing references going back as far as AD 200 or beyond, in Japan, records of the sport only travel back a few generations before disappearing into the forest along with the original, albeit illiterate, practitioners of tenkara.

Even the origin of the name, tenkara, is unknown. The phonetic reading of ten kara could give it the meaning of “from heaven.” However, the name is written in katakana characters, a Japanese syllabary mostly used for words of foreign or unknown origin. This leaves few clues but opens several theories on the original meaning of the word. The most common stems from the way a fly lands from a fish’s perspective, as if it were coming “from heaven.”

Until recently, in most parts of Japan, the method was referred to as kebari tsuri. Kebari means “haired hook” (artificially), and tsuri means “fishing.” In the late 1970s, as the Japanese rediscovered traditions such as tenkara that had flirted with extinction during periods of dramatic economic dislocation, a handful of tenkara enthusiasts began using the term tenkara exclusively to clearly differentiate the practice from other types of fly-fishing. Nowadays, in the appropriate context, it’s used to describe fly-fishing sans reel.

The adventure

I wasted no time getting to the mountains of Gifu prefecture, the region of Japan where tenkara possibly originated. Two friends from Tokyo met me at the airport, we loaded into a rented Nissan and immediately headed for the mountains. The suburbs of Tokyo sprawled endlessly on both ends of the city, a sea of lights with tiny rice paddies in lieu of backyards. Mountains on the horizon appeared impenetrable, abruptly bordering the suburbs as though the country were too small for foothills.

The seven-hour drive southwest was a bridge between two worlds, betraying how a mountain culture could have remained unexplored within a country the size of California. Traveling at sixty miles per hour I imagined how, just a hundred years ago, it would take a full day to cover what I did in ten minutes. I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years.

"I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years."

We arrived in Maze, a small mountain village of approximately 1,400 souls in the prefecture of Gifu. Kazuhiro Osaki, who goes by the name Rocky, and his wife, Ikumi, would host me during my stay. For several years, Rocky and his wife have managed the Mazegawa Fishing Center, a tourist center established on the banks of the Maze River to promote angling tourism and other activities in the area. Their home was quaint, my lodging a traditional tatami room with its typical grassy fragrance. A seat at the kitchen table provided a clear view of the mountains to the south. Being the monsoon season, sparse clouds frequently enveloped the mountains. I couldn’t have asked for a more scenic location or for better hosts—it felt like a dream.

Most mornings evolved into a pleasant routine of writing and taking care of the business side of Tenkara USA while drinking a cup of coffee and enjoying the mountain views. In the afternoons I visited the fishing center and tried to uncover the different layers of tenkara through fascinating interviews and encounters with individuals who made (and continue to make) its history. In the evenings, I’d try to fish the yumazume, loosely translated as the “evening activity period,” until it got too dark to see.

A living tradition

Perhaps the mountain culture of tenkara has always been too rich to ever really be at risk of true extinction. Talking to some early Japanese explorers of the tradition, I wonder how close Japan came to losing tenkara.

Eighty-nine-year-old Mr. Ishimaru Shotaro heard about my curiosities through the region’s social network. He came to the fishing center to meet this gaijin (foreigner) who was so interested in his tenkara. He guessed it was 1934 when he began watching a tenkara angler near his hometown of Hagiwara. He explained that approaching a stranger to ask about his techniques simply wasn’t done at the time. Keeping a subtle distance, Shotaro-san followed the angler for an entire summer, periodically going off on his own to try out the techniques he observed. This is how he learned tenkara, then taught others in the area, and is now often referred to as a tenkara meiji, or “tenkara master.” Without any records to prove otherwise, Shotaro-san may have been the rst tenkara teacher in the country.

I asked him why today’s young people think that fishing is difficult—despite the availability of books, magazines, and videos—even though Shotaro-san taught himself the practice simply through observation. He responded simply, “There were a lot more fish back then.” Mr. Shotaro described how at that time, when the damming of the rivers that accompanied Japan’s industrialization was far from complete, he often caught 100 fish a day, with a personal record of 150, numbers common and somehow sustainable among the professional tenkara anglers of the time.

“There were a lot more fish back then.”

When I met him, Shotaro-san couldn’t trust his body the way he did a decade earlier. His legs started giving out three years ago, and since that time, he had not visited the water. Nonetheless, one hour of talking about tenkara was just too much for him to bear. As he had done a hundred times in our conversation, every time he remembered a story about fishing and his youth, he smiled. But this smile was different. I could tell he wanted to fish again. In a very soft voice he turned to his nearby student and said, “Tsuri o shimashoo!”—“Let’s go shing!”

After helping him put on waders, his student and I assisted Mr. Shotaro into the waters of the Maze River. Mr. Shotaro said he wanted to fish with me, since he didn’t know if he’d ever have another chance. With a new vigor, his casting was fluid and precise, the manipulation of the fly enticing. In a stretch of river that had yielded few fish in the two months I was there, Shotaro-san got a fish to rise on his third cast.

Stolen technique

In the early 1960s, the practice of tenkara was as mysterious as it had been in the prewar period. Katsutoshi Amano, a name known to all Japanese tenkara practitioners, had to learn the sport exactly the same way Shotaro-san did before him. As Amano-san said, “Asking a man about his technique just wasn’t done at the time; I had to ‘steal’ the technique from him.” Ironically, given their age difference and the fact that both are from Hagiwara, there is a good chance the man Amano-san followed and mimicked was Shotaro-san himself.

Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, my principal tenkara teacher, and Mr. Amano were instrumental in popularizing tenkara among the Japanese starting in the late 1970s when Japan, at the height of its economic boom, began to rediscover itself and its traditions. In 1985, Japan’s largest TV network produced a segment on the sport, giving people throughout Japan an idea of what tenkara was about. Nowadays, newcomers can look it up online, watch videos, and choose from a collection of books and magazines that offer lessons on knots, flies, and techniques. A once-secretive practice that provided employment to landless peasants is now a source of fascination to urbanized Japanese and a growing number of participants in the United States and other countries.

Tenkara with a twist

Two months went by faster than the glimpse of a rising trout. But I was happy I had found the time to fish a little on a daily basis. My worst fear was that I’d end the journey wasting a lot of time and not “finding tenkara.” I feared my relatively reclusive nature would send me deep into the mountain streams searching for the soul of tenkara anglers from centuries ago, rather than seeking people who are alive and carrying on the tradition.

My fear of wasting time didn’t come true. I enjoyed incredible encounters with old masters, meetings with craftsmen, a very enjoyable time with my hosts and their friends, and a lot of fishing, too. But I also craved adventure.

The same isolation early tenkara fisherman enjoyed was a little more difficult to achieve in modern Japan. So we took to the challenge with canyoneering shoes, neoprene wetsuits, ropes, and harnesses, and our tenkara kit, mixing fishing with what is known as “shower-climbing,” a mix of canyoneering with climbing waterfalls. It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. Our portable gear didn’t add weight to our packs, and the telescopic rods could quickly be stowed away as we prepared to climb a waterfall. By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there.

"It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. ... By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there."

We set off on an expedition that took us to rugged tenkara-perfect mountain streams, far from the masses that leave many streams ravaged and devoid of fish. Out here, I finally felt the spirit of tenkara fishermen from eras gone by: They disappeared into the forests for weeks at a time, camping and fishing the streams, drying caught fish, and finally, when the catch threatened to be too heavy to carry out, headed back to the village markets.

We planned to build a fire by the river, where we would cook a trout “shioyaki-style”—only sea salt coating the skin, a firm branch serving as a skewer. And we would drink kotsuzake, a drink that, as I have come to appreciate, is underpinned with ceremonial and philosophical significance—though one shouldn’t picture a neat Japanese tea ceremony.

Kotsuzake is primitive and raw. Preparing and drinking it is an act of homage to the principle of not wasting the resources nature provides. After separating the bones from the meat, we placed them over the coals of the re to lightly roast and bring out oils and flavor, then immersed them into the warm sake. The result is sake with subtle and tantalizing fish flavors—all part of the Japanese mountain culture, and now a personal practice if I must eat a trout that I catch.

The cliff-hanger

Back on the treacherous, wet rock face, a small overhanging cluster of bamboo far to the left started to seem more reasonable the longer I clung immobilized by the waterfall. I normally would never trust plants to hold my weight over a fall that could potentially kill me, but at this point, adrenaline dictated my actions. I grabbed a bamboo stalk and slowly shifted the weight off my feet. I placed my trust in a root system that was out of sight under a thin veneer of soil. Through the patch of bamboo and other vines, I finally topped the cliff, beaming in relief. Under heavy rain, I wrapped an anchor rope around an ancient tree lying across the stream. When Futamura-san reached the top, he looked down at the pool below with a nervous smile and said, “Good job; difficult climb.” △

The Height of Hip: Kristallhütte

A slope-side hotel and hipster après-ski hangout in Austria's Hochzillertal

Hochzillertal / Tyrol / Austria

The Kristallhütte’s slogan — “Lifestyle on the mountain” — comes to life when locals and guests from around the world chill to hip DJ acts on the tremendous sun terrace with 360-degree views. The hotel and hipster après-ski hangout sits above 7,000 feet (2,147 m), slope-side, and offers eight Panorama guest rooms and four Alpine Lodge Suites.

“Cool like a hotspot for the in-crowd, cozy like a ski lodge, and posh like a luxury hotel,” owner Stefan Eder describes the Kristallhütte.

Sleep Responsibly: Feldmilla Design Hotel

The hotel in South Tyrol runs on clean energy from its own hydro-power plant

Campo Tures / Valle Aurina / South Tyrol / Italy The family-run Feldmilla Design Hotel is the first climate-neutral hotel in South Tyrol. The thirty-five light-flooded rooms, suites, and apartments offer panoramic views of the Dolomite mountains and the local castle. The hotel has a spa area, beauty farm, and restaurant. A wooden bridge connects the Feldmilla to the close-by village center.

“Design and sustainability are the two pillars of our philosophy,” says owner Ruth Leimegger. “Clean electricity from our own hydro-power plant and purchasing local, organic products allow us to keep carbon emissions very low.” Moreover, the Leimeggers compensate for unavoidable emissions by investing in an environmental project in Guatemala.

Nature Lovers

A photographer takes couples into the wild and shoots "Adventure Love Stories"

Marrying his love for the outdoors with his gift for putting people at ease, Seattle-based wedding and adventure photographer Greg Balkin shoots couples in the wild. The self-proclaimed professional third-wheeler takes his subjects backcountry camping and wakes them at sunrise to capture “Adventure Love Stories,” set in alpenglow.

What does a dollar still buy you today? Ask Greg Balkin and he might tell you, a future built on your passions. That’s what the soft-spoken outdoorsman bought himself when he purchased Brightwood Photography from a friend for this symbolic amount.

The happiest day — forever captured

Prior to launching his photography business, Balkin worked full time in the film industry for six months before realizing his career got off in the wrong direction. Fascinated by the fabric of relationships, he started shooting weddings in 2013, many of them outdoors. “The outdoors has been a huge part of my inspiration,” says the keen backpacker. “It’s where I find peace and love.” Nevertheless, the young man is anything but a lone wolf. His pursuit of happiness in the wilderness is fueled by a desire to mesh with fellow nature lovers. “It’s about connecting with people when they’re happy,” Balkin says. “That’s why I love shooting weddings. It’s their happiest day, and that’s awesome to experience.”

Yet he soon began to ponder how to combine his love of nature and comradeship with his passion for photography—all while making a living. “The whole idea just pieced together and made sense,” he says, looking back at how he created the photographic genre he now calls “Adventure Love Stories.” After shooting dozens of weddings over the past three years, Balkin knows the big day’s pressures and expectations can obscure a couple’s natural mien and candid moments. “Sometimes, I can get them to chill out and focus on each other,” he says. “Most times, they’re trying the best they can to hold on to the day.” So Balkin thought of a better way to help the couples be at ease with each other—and their photographer—and remember why they came together in the first place: He takes them into the wild. “When they’re outside, they get to goof off, and it pulls the stress away from them. It gives them a chance to not worry about what’s back home.”

I got you, babe

The shoots, Balkin says, sometimes feel like a relationship-building boot camp, testing a couple’s trust as he asks them to climb on top of a boulder or stand on the edge of a cliff. “I’ve definitely heard couples say, ‘I got you. I’m not letting go. We’re in this together. I’m standing right next to you, and we’re just going to hold on tight.’ ”

It doesn’t escape Balkin that there is plenty of potential for things to get awkward. “My job is watching people kiss and taking pictures,” he says, laughing. “I’m a professional third-wheeler.” From behind the lens, the photographer gets an intimate glimpse into a romantic relationship. For a short time, he joins two people on their very personal journey. Moreover, he shoots his Adventure Love Stories in remote locations, deep in the national forests or high among mountain peaks. To be there in time for the best light at dusk or alpenglow at sunrise, Balkin and his subjects typically camp together in the backcountry. Still, he knows when to retreat and give the couple space and time to be alone.

“My job is watching people kiss and taking pictures. I’m a professional third-wheeler.”

Veronica and Craig

One pictorial Adventure Love Story—set among the trails and peaks of Deer Park in Washington's Olympic National Park—tells of Veronica Vanderbeek and Craig Torgerson’s deep connection. Balkin met Vanderbeek through a mutual friend at the time she was planning her upcoming wedding. Although he wasn’t available to shoot the actual wedding, the bride-to-be was quickly enthusiastic about his idea for an engagement photo shoot in the wilderness.

When the time came to take Vanderbeek and Torgerson camping for the shoot, a flat tire set Balkin back on the eight-mile dirt road. They finally arrived at the peak just as the sun was setting. “We ran out to the big rock with the blanket and just had fun with it for twenty minutes while we still had light,” Balkin remembers. “Greg spent the whole weekend with us,” says Vanderbeek. “He set up our campsite, and he cooked us a gourmet dinner and breakfast. He was a friend hanging out with us, rather than a professional we hired.” The group sat around the campfire at night before Balkin retreated to his car for a few hours of sleep.

It rained the next morning. But Vanderbeek defied the drizzle with grace, wearing the white, flowy dress she had packed for the photo shoot. “The place was freaking gorgeous,” remembers Balkin. “For the next couple of hours, we just ran around, and I called out to them, ‘Turn around and look where we are, because it’s super pretty.’ ” With a deeper understanding of his subjects as a couple, the photographer captured something outside of visual representation. “Veronica and Craig are both quiet people, but you can tell they are willing to sacrifice a lot of themselves for the betterment of the other,” Balkin reveals. “Their love is so apparent.”

A love story set in nature

Disarming wilderness, breathtaking landscapes, and the couples’ unconcealed intimacy are protagonists in the Adventure Love Stories, too. Often, Balkin’s clients already know what place they want to explore together, and frequently choose a backdrop that perfectly reflects who they are as a couple. “I love watching people become awestruck by the places we shoot in or watching them play on rocks or run around the ocean,” he says.

The photographer wants to shoot more Adventure Love Stories, holding on to what he cherishes about wedding photography: spending a day with people and capturing their memories—minus the nuptial stress. “I love getting to celebrate them in a place that means a lot to both them and myself,” Balkin says. “I find it important to be outside. How cool is it that I get to connect with people and take their pictures and make memories in beautiful places, such as Big Sur, Joshua Tree, Deer Park? I love it.” His natural empathy and connection with others—a powerful part of humanness rendered in conscious awareness—is a landscape in itself. The camera is only a tool for the photographer’s outward expression of how he understands others.

"I love watching people become awestruck by the places we shoot in or watching them play on rocks or run around the ocean.”

The leads in Balkin’s Adventure Love Stories will forever have a special place to revisit, an adventure to relive. Looking at the framed photos in their Oregon home today, months after they tied the knot, the Torgersons revel in Balkin’s pictorial storytelling, hoping the scenes are indicative of the future they will share: a life filled with exploration—new ideas, new people, new adventures. Their favorite picture is one that shows them looking out over the mountain edge, because it reminds them about the terrain they’ve conquered to get to where they stand, while envisioning the expanse of their future lives together.

“It’s a picture that shows us supporting each other,” says Torgerson. His wife also cherishes the photos of the two of them looking at each other: “Seeing the beauty in each other and the beauty around us is really special to capture,” she says. Hungry for perpetual change, the newlyweds, who fittingly met on a hiking trip to Colorado, are anchored only in knowing they want to be together. They are each other’s idea of home, security found in a person rather than a place. As she puts it simply, “You have your sense of home going with you when you travel with the one who you love.” △

“You have your sense of home going with you when you travel with the one who you love.”

Behold

Through eyes and lens: A travel photographer hikes the Banaue Rice Terraces

To photographer Chimera Rene Singer, seeing the world from a mountaintop is a lot like studying an image—geometric shapes shift, nature becomes imaginary, real objects turn into mythical whatsits. When we look at an image, the image is not the subject it depicts, just as surrealist artist Rene Magritte’s “pipe” is not a pipe. What we see creates an entirely new sensation. Examining an image can be like tracing dragons and ships in the clouds. The experience of climbing a mountain can be like studying a picture. From up there, we read the world as visual poetry created by the lines and shapes of unidentified objects. Our focus is redirected. As we face significant altitude, we also rediscover our acquaintance with the earth and air that feeds us. The heightened perspective awakens a grounding humbleness we rarely feel elsewhere.

"The experience of climbing a mountain can be like studying a picture."

A few months ago, I visited the Banaue Rice Terraces in the Philippines with a group of other photographers. Rain clouds hugged the mountains as sweat clung to our faces. We lingered to snap images and paused to gaze toward the miles of green, before our guide ushered us on until we reached Tappiya Falls.

“From up there, we read the world as visual poetry created by the lines and shapes of unidentified objects. Our focus is redirected.”

The mountains that stretched before us were make-believe. We were in a children’s adventure story. We were like birds, looking down at our prey, watching our young, and searching for food. The mountains, the gleaners, and the specks of rooftops were splashes of yellow, green, and red. The land became geometry and color. Rocks transformed into fascinating objects as we saw them in the grander scheme of a mountainside, and distant gleaners became silent mobile shapes that we observed without hindrance.

“The mountains that stretched before us were make-believe. We were in a children’s adventure story.”