Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Quietly Swiss

A chalet shaped after the surrounding mountains of Les Jeurs

Local building nostalgia and the majestic surrounding mountains guide Geneva architect Simon Chessex in designing a young couple’s modern dream house, built on family land. Olivier Unternaehrer, a Geneva-based attorney, and Céline Gay des Combes Unternaehrer, a professional harpist, had long dreamed of a mountain retreat where they could spend weekends and holidays, someday raise a family, and eventually retire. So when the young couple had the opportunity to own a plot in the mountains of Les Jeurs—land that had been in Céline’s family since the 1800s—the decision to build there was obvious. A hamlet above the road to the Col de la Forclaz mountain pass in the Swiss Alps, Les Jeurs was the perfect place.

Adventures in architecture with Lacroix Chessex

Longtime friend Simon Chessex, a founding partner of the Geneva architecture firm Lacroix Chessex, was the natural choice as Olivier and Céline’s architect. The couple shared their requirements, nice-to-haves, and wildest dreams with Chessex and his team, and the collaborative design process was “a beautiful adventure,” Olivier says. “We believe—and we think they do, too—that we brought the best out of each other throughout.”

Simon Chessex founded Lacroix Chessex with fellow Swiss architect Hiéronyme Lacroix in 2005, based on their shared belief that good architecture is inspired by two factors: “a thorough analysis of the site, in which micro and macro scales are directly related, and a careful and critical reading of the brief that is given to us,” Chessex says. Both partners strive to approach design and construction without preconceived ideas of what a project should become. The role of the architect, says Chessex, “is that of a tailor who designs and realizes a client’s vision with care, passion, and accuracy.”

Roots on family land

The home’s spectacular location near Trient was destined. Céline’s ancestors were native to the region. As a child, her own father spent many holidays camping on the very land where Céline and Olivier would later build their chalet. Sharing the same dream of raising a family in these majestic mountains a generation earlier, Céline’s parents relocated from Geneva to Les Jeurs in the 1970s. And decades later, as a couple, Oliver and Céline spent weeks at a time, even one entire summer, vacationing in the mountains. When Céline’s father offered them a plot of the family land, their decision to build there was a simple one.

Like generations before them, committing to the family land for a lifetime felt timely. They pictured a mountain retreat where Céline could play the harp, where they could soon raise a family, and where they would eventually retire. “Our vision was to build a house that would be a place to welcome friends and family, that would fit well in the local and mountain landscape, yet that would be modern,” Olivier says. Chessex absorbed their hopes and dreams and presented plans for his reinterpretation of a traditional Swiss chalet.

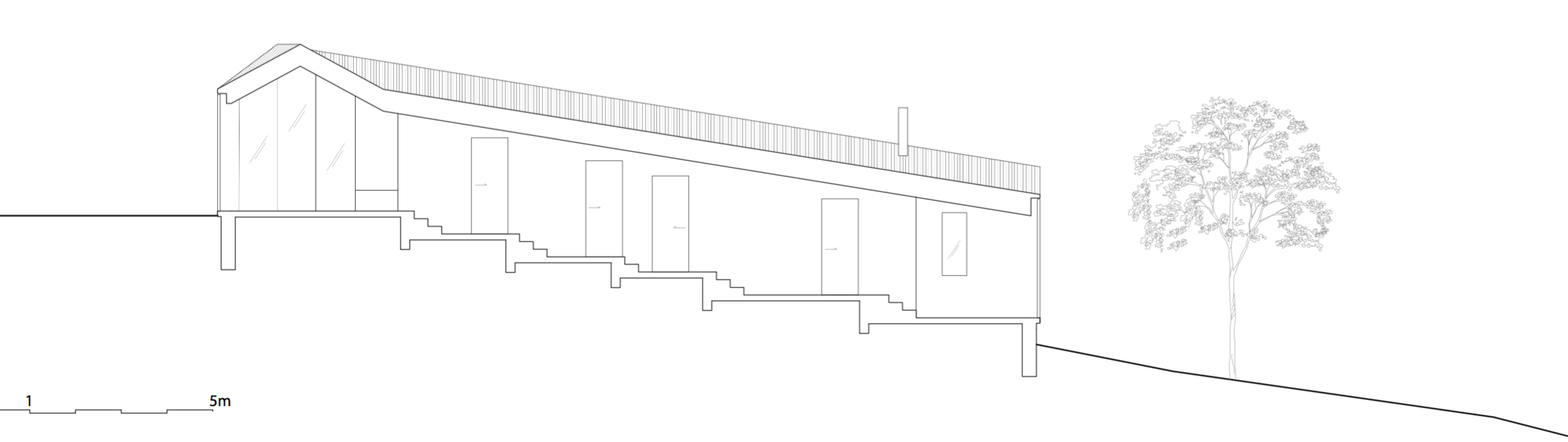

The architect drew upon the region’s historical stone and wooden mountain homes for inspiration and let the alpine landscape guide his design. “It’s clearly a site-specific project,” Chessex notes. “The shape of the building comes from the profile of the surrounding mountains.” It was important to Olivier and Céline that the house was modern yet also fit into its “quite wild” setting. And Chessex’ design beautifully harmonized with the local village homes and the spectacular scenery. Aware that a closed, large volume would disturb the harmony of scale, the architect designed the structure as two parts forming a “V.” They are connected by the entrance on the mountainside and are separated by a forty-five-degree angle that opens toward the valley. “The numerous windows give many opportunities to just look outside and bring the outside to you, just as if you were looking at a painting,” says Olivier.

"The numerous windows give many opportunities to just look outside and bring the outside to you, just as if you were looking at a painting."

The landscape and the design are in “smooth and direct relationship,” he continues—inside the “cozy chalet atmosphere” and outside views of the “playground.” Reinterpreting the functional design of historical Swiss barns that were elevated from the ground to preclude mice from entering, Chessex situated the home on a cantilevered concrete plinth. He chose grey fir wood for the home’s exterior and natural fir for the inside because the material is both naturally weather-resistant and economical.

Bridging cultural integrity and modernity with stone and wood

Chessex used the same wood for the walls, ceilings, and floors so that the interior uniformly appears as a single unit of space. This element of the composition is unsurprisingly one of Olivier and Céline’s favorites. Olivier believes the house bridges cultural integrity and modernity by keeping things as simple as possible. The natural quality of the wood reminds him of older mountain dwellings marked by the years, wind, and snow.

At the same time, Chessex took the liberty to put an updated twist on traditional Swiss mountain architecture by designing the home as two connected wings: The main entryway is “folded where the two buildings unite,” creating a V-shaped front door and window. Olivier shares that abandoning tradition to incorporate modern eaves “clearly surprised some people at first,” but was ultimately very well received. The owners particularly enjoy the the roof’s geometry and the living room window that reaches down to the floor.

The rugged mountain location complicated the construction process. Inaccessible by truck, the site required helicopters to fly in prefabricated wooden pieces. Additionally, Chessex initially worried that the authorities and local population might find the house too radical for the village and feared he may be denied a building permit.

Despite the challenges, Olivier and Céline were able to move in exactly two years after hiring Chessex to design and build their home. Olivier describes the experience: “Quite simply, one day we could walk in, and the house was no longer the worksite it had been for the last year, but a complete house in which we could stay. It was quite an intense and beautiful moment.”

"Quite simply, one day we could walk in, and the house was no longer the worksite it had been for the last year, but a complete house in which we could stay. It was quite an intense and beautiful moment."

Olivier and Céline quickly fell in love with the mountain house and now spend their weekends there after a week’s work in Geneva, where they have been renting the same apartment for more than ten years. Olivier contemplates how the modern chalet is “majestic, like a quiet force, as the mountains can be.” From the exterior, “The house appears to be changing shape depending on the viewing angle,” he remarks. Inside, the home feels “peaceful, relaxing, and quiet” with direct views of nature and mountain wildlife.

Visiting friends often refer to the couple’s hideaway as their “nest,” given it’s high mountain perch—a dual meaning, since the couple hopes to raise a family in their “lifetime house,” as Olivier calls it. “We intend for our house to become a family home and at all times to remain a place where friends and guests can come and share good times with us.” What started as their self-admittedly “crazy” dream materialized into a beautiful sanctuary on the mountainside, a home daringly designed to mirror the innate artistry of the surrounding landscape and to nourish creativity and community.

"We intend for our house to become a family home and at all times to remain a place where friends and guests can come and share good times with us."

Scandinavian Inspiration in the Canadian Woods

Villa Boréale by CARGO Architecture

Villa Boréale by CARGO Architecture is set in the heart of Québec's Boreal forest and near the ski area Le Massif de Charlevoix. The simplicity of Scandinavian design, the vision of a contemporary interpretation of a Québec cottage and a modern barn, and the materials in their raw appearance influenced the concept for Villa Boréale by CARGO Architecture. The matte black metal cladding contrasts the pale tones of the Eastern white cedar, the concrete and the white interiors.

Landscape, the Architect

The calm design of the V-Lodge in Norway responds to the down-sloping terrain

High up in the mountains of Norway, the V-Lodge's simplicity in design and choice of materials speak to its wild surroundings. “The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal,” Oslo architect Reiulf Ramstad says about the minimalist mountain house he designed for a family of six. “Its form is a dialog between the landscape and the client.”

"The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal."

Ramstad’s architecture speaks to the people and the place he creates it for. The self-described generalist, who designs modern homes as well as hotels, churches, and civic projects, says today’s one-size-fits-all designs may be rational, but, “Architecture is more than an economic business; it’s a humanistic business. The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals.”

Creating only what is essential, never more than necessary, particularly interests Ramstad. The V-Lodge a prime example: His clients, who enjoy nature and simply being together, away from their busy lives in the city, had originally commissioned a much larger house to be built on their land 200 kilometers (124 miles) northwest of Oslo. Discussing the project with the architect, however, they understood that a smaller, more sustainable cabin would better suit their needs and accommodate a change in family composition and a mix of generations in years to come.

"The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals."

The Right Man for Wild Territory

“We had found the most beautiful site on the outskirts of the Norwegian mountain area called Skarveheimen, a wild territory between the better-known and -visited Hardangervidda and Jotunheimen,” says Lene, who shares the remote retreat with husband Espen, their three grown children (twenty-two, twenty, and eighteen years old), and their eleven-year-old daughter (“our afterthought”). Plus, not to forget, labrador Vilma. (The family prefers we do not print their surname).

The couple had searched for the right architect for quite a long time. “Someone who could gently transform the landscape and, at the same time, preserve and strengthen the qualities of the site,” Lene says.

Influenced by two very different cultural contexts—Scandinavian and Latin—the Nordic architect’s business and design philosophies made him the right man. Born in Oslo, Ramstad, who received his Dottore in Architettura from the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, deliberately chose to study in Venice, Italy, to experience life without cars. He founded Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter in 1995, without previous experience. He has never worked for another firm. “It may not be the most rational way, but it’s a very interesting experience in that you have to invent most things,” reflects the credo of the now internationally recognized architect.

Lene, a graphic designer, and Espen, an executive in the gas and pipeline industry, handed Ramstad a long list of functional needs and aesthetic preferences along with a budget, but otherwise, they gave him free hand. “We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking,” Lene says.

"We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking."

Walking the Landscape Inside

The remote retreat sits near timberline at 960 meters (3,150 feet) above sea level, high above spread-out villages down in the valley. The architect took his own site survey, obtaining more precise data than the public maps revealed. “We needed finer measurements so we could create a better dialog between the building and the landscape,” Ramstad illustrates. “The building itself can follow the topography, instead of peaking and ruining the place.”

Guided by unspoiled mountain views and the directions of the wind and the sun, the V-shaped house design is Ramstad’s response to the landscape. While one side of the V sits on a horizontal level, the other side steps down with the terrain, resting close to the ground. “You can walk the landscape inside the house,” says Ramstad. The small scale of the rooms in this private wing reflects nature’s small scale right outside the windows there — small plants and trees, the snow lying close to the ground. “It’s a very simple way of responding to different scales and intimacy, to public and private spaces.”

"You can walk the landscape inside the house."

The horizontal wing of the 120-square-meter (ca. 1,300-square-foot) house accommodates the entrance and the main living area with the kitchen and the dining room. The other part, which follows the downward slope, houses the bathroom, three bedrooms and a lounge area at the far end. The V culminates with the glazed wall at the confluence of the two sections.

A Spatial Kaleidoscope

Ramstad’s design uses only about a tenth of the land, letting the rest be nature. “Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature,” Lene says. “We are carefully taking the terrain close to the cabin walls back to what it was, as if the cabin is growing out of the ground. Working with soil, stone, and vegetation is part of our life at the cabin.”

Ramstad perceptively oriented different elements of the structure toward distinct sights, offering views of different kinds of landscape. “The architecture is a spatial kaleidoscope,” he says. The floor-to-ceiling walls of glass create immediacy with the outdoors. “The glass cancels the barrier between inside and outside,” the architect continues. “Sitting in the living room is like having these huge landscape paintings that are actually views towards the mountains. So working with very subtle and slim glass details and without frames, the window becomes just a transparent layer, and not a window in itself.”

"Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature."

The exterior is entirely clad in untreated, short-hauled pine; inside, walls and ceilings are paneled in pine plywood. “Using one material gives wholeness,” Ramstad says about the lodge’s minimalist appearance, which is also void of extra decorations. “When the wood oxidizes, it will have this patina that blends into the landscape, into the colors of the surroundings. The design and carpentry of fixed furniture and other features, including lamps, kitchen, bathroom, wardrobe, tables, and beds, was done by the owners themselves. Says Lene: “We like to design and build things together, and that is an important part of our leisure time.”

100 Days of Solitude

“Going to the cabin for weekends and holidays is definitely different from our life in Asker by the Oslofjord. A three-hour drive from home, and we are at the cabin, where we have everything we need for recreation — but not more than that,” Lene says. “However, the most important thing is being together, and at the same time having the freedom to be on your own.”

In winter, the family cross-country skis right out of the cabin’s door. In summer, they hike in the surrounding mountains. On warm days, they go for a swim in the nearby mountain lake or a dip in the River Lya. “This has definitely become the all-year cabin we wanted,” Lene raves. “We used it exactly 100 days the first year.”

The architect is equally pleased. “Spatially, this is not a very fancy project. It is very calm, yet at the same time, has very clear, distinct design solutions,” Ramstad says. “I’m very happy with it.”

V-Lodge Photo Gallery

Extreme Shelter

Living ecological alpine pods in the Italian Alps

Test laboratory mountains: The Italian architect duo behind LEAP (living ecological alpine pods) design-builds modular solutions for harsh high-altitudes. Luca Gentilcore and Stefano Testa, founders of LEAPfactory, Turin, Italy, share a strong passion for alpine adventure and avant-garde architecture. “We love exploring the limits in both fields,” says Testa. “LEAP, to us, represents quality of life and a love for nature, particularly pure nature, and the devices humans build to survive — may these be sweaters, camping tents, or high-tech buildings. We do not limit ourselves or our activities.”

"LEAP, to us, represents quality of life and a love for nature, particularly pure nature, and the devices humans build to survive — may these be sweaters, camping tents, or high-tech buildings."

The mountains are their test lab. “The extreme conditions, the essential dialogue with a marvelous and strong nature, the loosening of human rules and customs — all this makes mountains the best setting for focusing our goals.”

Both men are avid mountaineers. “The mountains are where I feel free, and nature is the vehicle to look for the deepest sense of life. I spent thirty years of my life rock climbing around the world. I climb less often now; it’s still the best way for me to have time to breathe deeply and to find my balance,” tells Testa. A perfect day? “Climbing a perfect sequence of beautiful holds on a sunny rock wall and, at the end of the day, a dinner around the fire with my family and friends in a clearing, the scent of tree sap in the air.”

Continues the architect, “After many years of studying, practicing, and teaching architecture, LEAP is a way of bringing together my two souls — nature and artifice, technology and beauty. This is the path of LEAP design research.” Testa studied the masters of modernity, the Italian tradition of the fifties, and the radicals' tenets of the seventies. He also worked with contemporary artists. “All these things influence my work today,” says Testa, yet he adds, “I love to think there is not one design style in my work. Instead, there is a continuous search for the right answer to specific questions and places.”

"After many years of studying, practicing, and teaching architecture, LEAP is a way of bringing together my two souls — nature and artifice, technology and beauty. This is the path of LEAP design research."

To Gentilcore, the mountains have meant different things throughout different periods of his life — fun, exploration, culture, relationships with the force of nature and with other people. “The mountains for me evoke these emotions that have the power to remove the filters contemporary society imposes on us. In that sense, the mountains have become a fundamental component of life for me that I can't do without.” Last summer, Gentilcore hiked with his wife, their two children, and a donkey through the wild landscapes of the Massif Central in France for fifteen days. There, I felt really happy.

"The mountains for me evoke these emotions that have the power to remove the filters contemporary society imposes on us. In that sense, the mountains have become a fundamental component of life for me that I can't do without."

Respect for the mountains is innate for Gentilcore. “It's respect for nature itself and the culture that the mountains represent. I think this sentiment is originally part of all of us, but it is often clouded and hidden.” It has helped him discover how efficiently humans and nature respond to extreme, hostile environment. “To design for the mountains, we need to study successful sustainable solutions we can adapt to urban and ordinary contexts in the future.” He’s inspired by fields other than architecture that offer alternatives to the traditional way of building. “For the Gervasutti project, for example, we looked at aeronautics and boating; other times we have turned to the world of high-end furniture. For this reason, our projects are almost always new construction systems or new building types.”

Nuonuova Cappana Gervasutti, Mont Blanc, Courmayeur, Italy

Gentilcore and Testa relish untouched alpine nature. But if they do put a dwelling on a pristine peak, blending in isn’t the program. Above preservation, the designers aim to enrich the diversity and quality of an inhabited, inherited landscape.

Hence, when the Turin Alpine Club commissioned the new Gervasutti hut under the east face of the Grandes Jorasses in the Mont Blanc massif, the architects proposed what they now call “an ambitious solution.” It worked. “The site is very complex: a very small terrace on a rock buttress, in the middle of Freboudze glacier,” Gentilcore describes.

Rethinking the relationship between humankind, nature, and artifact, the two gave rise to a new generation of alpine bivouacs: an entirely prefabricated modular shelter that is airlifted by helicopter to its remote location and installed in only a few days, with minimized endeavor and without permanently altering the sensitive hosting place. “Modular design is a technical strategy to minimize the necessity of construction work on site. This is fundamental in fragile environments — and for our approach of ‘living in nature on tiptoes,’ ” says Testa, who has a PhD in interior design and has taught interior design and architecture and urban design at the School of Architecture of the Politecnico di Milano and industrial design at the New Academy of Fine Arts, also in Milan.

Transporting the new Gervasutti refuge by small helicopter to its installation site, high up between Haute-Savoie in France and Aosta Valley in Italy, was a lofty feat. “The typical aircraft used in mountain regions can load around 800 kilograms (1,764 pounds) up to 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) above sea level, so we realized four modules, entirely equipped, within that weight limit,” Gentilcore says. “At the same time, we had to guarantee very high mechanical resistance, due to the extreme environmental conditions. After several tries, we got to the final solution with an innovative prototype of a fiberglass shell.”

The high-tech tube thoroughly redefines the model of the traditional alpine bivouac built for survival, not comfort. “With the Gervasutti project, we aimed for something between a bivouac and a refuge,” Gentilcore says. “The comfort comes from cutting-edge technology, much like with contemporary mountain gear and clothes. But its environmental footprint is way lower than that of a refuge.”

"Modular design is a technical strategy to minimize the necessity of construction work on site. This is fundamental in fragile environments — and for our approach of ‘living in nature on tiptoes."

Stand-out Design

Gentilcore, who graduated cum laude in architecture from Politecnico di Torino in 2004, says much has been said about the aesthetic impact of the Gervasutti. “We thought, in the glacier landscape, there is no building tradition. And we didn't follow a mimetic approach relating to the strong natural environment. We designed a technical shape, and the shelter became an extraneous presence in the landscape.” The visual statement was purposive, beginning with the colors — white like the snow and the ice and red for visibility. The pattern is an homage to the traditional mountain sweater and, not least, part of LEAP’s corporate design.

Gentilcore interposes, “We also have to say that the circulated photographic portraits of the Gervasutti are completely different from the tiny, diminishing presence of the building when observed in person in the surroundings of this majestic landscape.”

The new Gervasutti shelter has become a hiking destination. “Last year, more than 600 people signed the hut book,” says Gentilcore. “Before our installation, the Freboudze valley, one of the most beautiful valleys on the Italian side of the Mont Blanc massif, had just twenty visitors per year.”

Founding Leapfactory

The partners reveal that the research and resources they invested in the Gervasutti project were utterly disproportionate to the realization of a single building. “We decided to found LEAPfactory and to develop a special building system, the LEAPs1, to commercialize it,” Gentilcore looks back. The year was 2013. The s1 was the first LEAP product.

The living ecological alpine pods are completely reversible by design, an essential ecological benefit of the s1 system. No concrete foundation. No ground alterations. “It leans on legs anchored to the rock with bolts,” Gentilcore explains. “Working at 3,000 meters of altitude is really hard — for the people and the ecosystem — so every activity on site needs to be minimized.” What’s more, by virtue of the extreme lightness of s1’s components, the number of required “heli rotations” (flights up the mountain and back) equals the number of modules. An individual module that sustains damage can be flown off site for repairs.

The modular structural sandwich–constructed shell, the quintessence of the s1 system, is made of a sophisticated synthetic composite compound, similar to materials used in manufacturing competition speedboats. An additional thermo-reflective insulation layer provides an advantageous microclimate inside the pod, even without a heating system. Warmth comes from thermal sources such as a cooking stove and even the inhabitants’ body heat.

A photovoltaic film integrated into the pod’s shell powers electrical devices. There is an Internet and a radio connection. A remotely controllable digital system monitors various functions of the s1, for example, energy autonomy, and provides information about internal and external weather conditions.

The configurable single-function modules (entrance; living module with kitchen, dining area, and pantry; sleeping quarters; bathroom) allow for flexible functional programs. “The big window at the extremity, ‘the eyelid,’ as we call it, transforms the building into a landscape-watching machine,” Gentilcore says.

Eco Hotel Leaprus 3912, Mount Elbrus, Caucasus, Russia

In September 2013, LEAPfactory installed an eco hotel for the North Caucasus Mountain Club as the first in a series of projects intended to encourage tourism in the region. LEAPrus 3912 comprises four tubes, built from prefab s1 modules, on the south side of Mount Elbrus, Russia. The refuge sits almost 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) above sea level along the standard route to the summit.

“The LEAPrus project was even more ambitious compared with Gervasutti,” Gentilcore says. “Fifty beds, a restaurant with kitchen, bathrooms with warm showers, heating in every room, a system to melt the snow to get water.” The hotel today operates year-round, hosting skiers in winter. “The off-grid functionality was demanding. We built a plant that produces energy from the sun and wind.”

Like the bivouac pod in Italy, the entire LEAPrus structure was installed in a few days, once again using helicopters. “We had less time than originally scheduled because all the operative helicopters in the region were in Sochi, busy with building the Olympic facilities. We remember the thirty-eight heli rotations over three mornings very well . . . and the evening of the third day, when our staff rested in our buildings that were just assembled and outfitted with electrical light, heating, and the operative kitchen,” says Gentilcore. “A super spaghetti party was organized, after many Russian soups in the construction barracks the days before.”

That night, Gentilcore slept right in front of the eyelid. “I will never forget this experience, the main Caucasian mountain range beneath me, in the sunrise . . . ”

Pod Lifestyle: LEAPS1 as Private Residence

Aside from the extreme conditions of Gervasutti and LEAPrus, Gentilcore says his company’s goal for the s1 system was to apply today’s best building practices, with particular focus on the ecological process. LEAPfactory has received many inquiries about the s1 as residential dwelling, although no one has realized it as tiny house or weekend cabin yet. “The LEAPs1 is a really sophisticated product, and it's quite expensive,” says the architect. “We can imagine s1 as an efficient off-grid house in a beautiful forest . . . with the ease of moving it to a new place.” △

Photos by Francesco Mattuzzi