Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Editor's Choice: Journey to Japan

The Beauty of Use

Hidden in the Japan Alps, a Czech-born artist makes woodstoves that match the simplicity of Japanese interiors. Read more »

The Skyward House

Japanese architect Kazuhiko Kishimoto designs a human-scale house for a retired teacher. Read more »

Repair With Gold

The Japanese tradition of wabi-sabi. Read more »

A Platform for Living

A weekend refuge in Japan’s Chichibu mountain range consists of a simple larch wood structure and two North Face tents for bedrooms. Read more »

Zen and the Art of Knife-Making

Using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, a blacksmith in the Japan Alps makes knives so delicate and dangerous they turn chopping into an artful act of passion. Read more »

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. Read more » △

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel

Upon returning from Japan, my mind was filled with the mountain culture of tenkara, a traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. I had to share my discovery with the people at home. My next journey was founding Tenkara USA.

Clinging to mossy rock with half my body under a waterfall, I watched the torrent crash into a small basin fifty feet below, sending mist into the air and soaking my companions. Mr. Futamura observed apprehensively. Next to him, Mr. Kumazaki preferred to stare at the pool in front of him for any signs of iwana, the wild char found in the mountains of Japan. A fishing rod, small box of flies, and spools of line and tippet were stowed away in my backpack. No reel required.

As tends to happen with shing, we lost track of time somewhere along the way and now faced the crux of the trip. It was seven o’clock in the evening and would soon turn dark inside this lush forest. After a full day of rappelling, swimming through pools in impassable canyons, climbing rocks and waterfalls, and, of course, shing, we were all tired. The route ahead looked straightforward and within my comfort zone, the only caveat being a very wet climb.

My task was to climb to the top, set up an anchor, and belay my partners up. Twenty feet from the top, features on the rock face disappeared on the drier left side and forced me closer to the waterfall, where thick moss oozed like a wet sponge. I was long past the point of no return. I pushed past the fear and focused: hands and feet, hands and feet, hands and feet. The banter between Futamura and Kumazaki suddenly stopped. All sounds, including the roaring of the waterfall, seemed to vanish.

Getting there

My trip to Japan was a journey of discovery. For two months, I stayed in a small mountain village, learning everything I could about the one thing prompting my journey: tenkara.

In reality, I already knew a lot about tenkara. Three years earlier, on my first trip to Japan, I introduced myself to this traditional Japanese method of fly-fishing that uses only a long rod, line, and fly—no reel. After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love. I imagined how great it would be for backpacking and introducing people to fly- fishing in a simple, fun way. There were just so many possibilities.

"After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love."

With little information and no gear available stateside, I took on the task of introducing tenkara to the United States. Over several long months, I created Tenkara USA and since 2009 have been introducing tenkara to anglers outside of Japan. However, despite the knowledge I gained in the last three years, particularly under the tutelage of Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, Japan’s leading authority on tenkara, I knew there was much more. Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers.

"Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers."

History of tenkara

Just as the practice of metalworking appeared independently in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East and among the Incas in South America, evidence suggests that fly-fishing emerged in Europe and Japan independently of one another. Tenkara is similar to the original mechanics of fly-fishing practiced by the likes of Dame Juliana Berners and Charles Cotton, the best-known historical practitioners of fly-fishing in the West. Anglers have practiced similar fixed-line methods in many other parts of Europe, including Spain, France, Italy, and Poland. Yet, unlike the original Western fly-fishing methods, tenkara still lives in Japan.

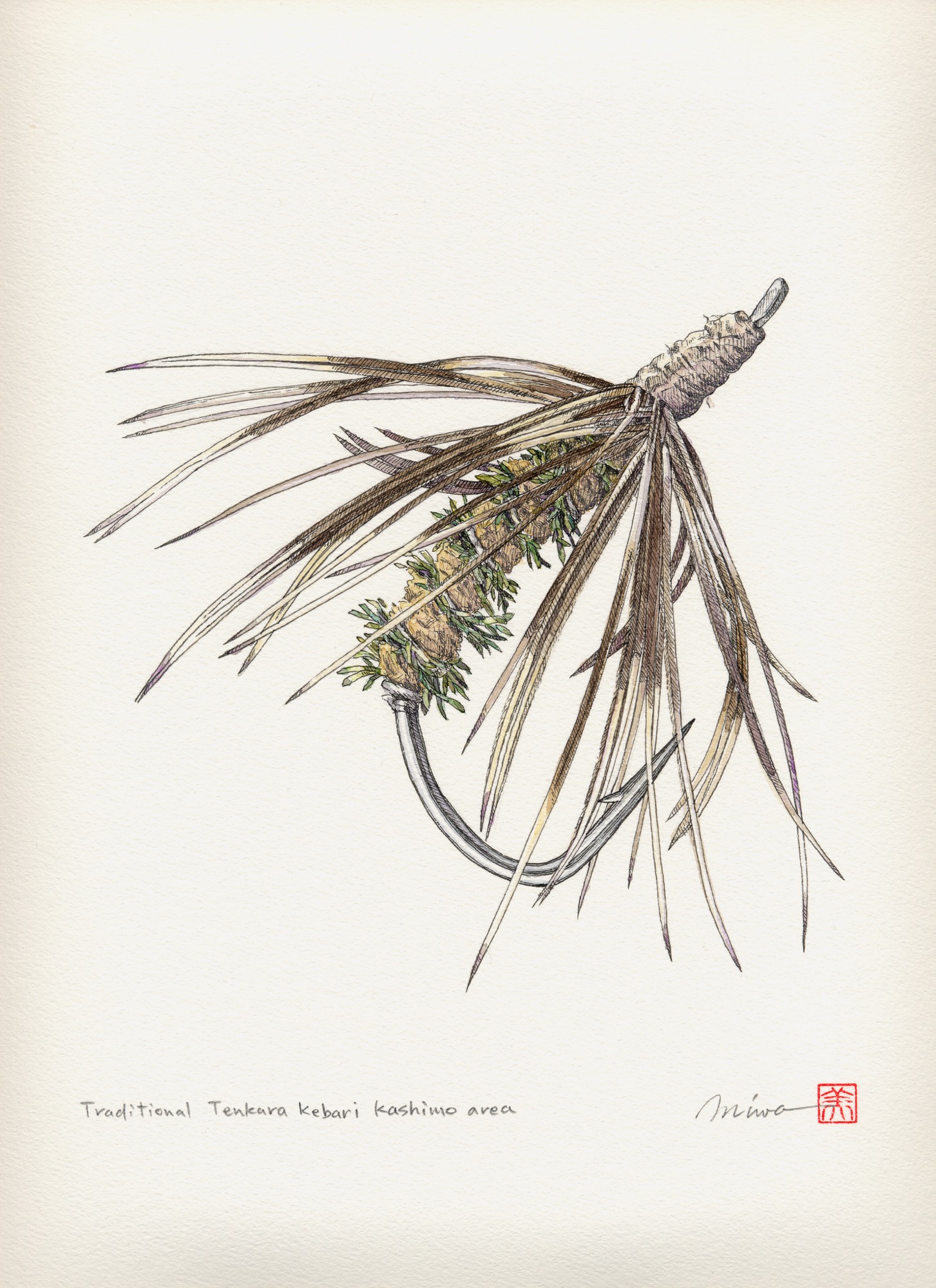

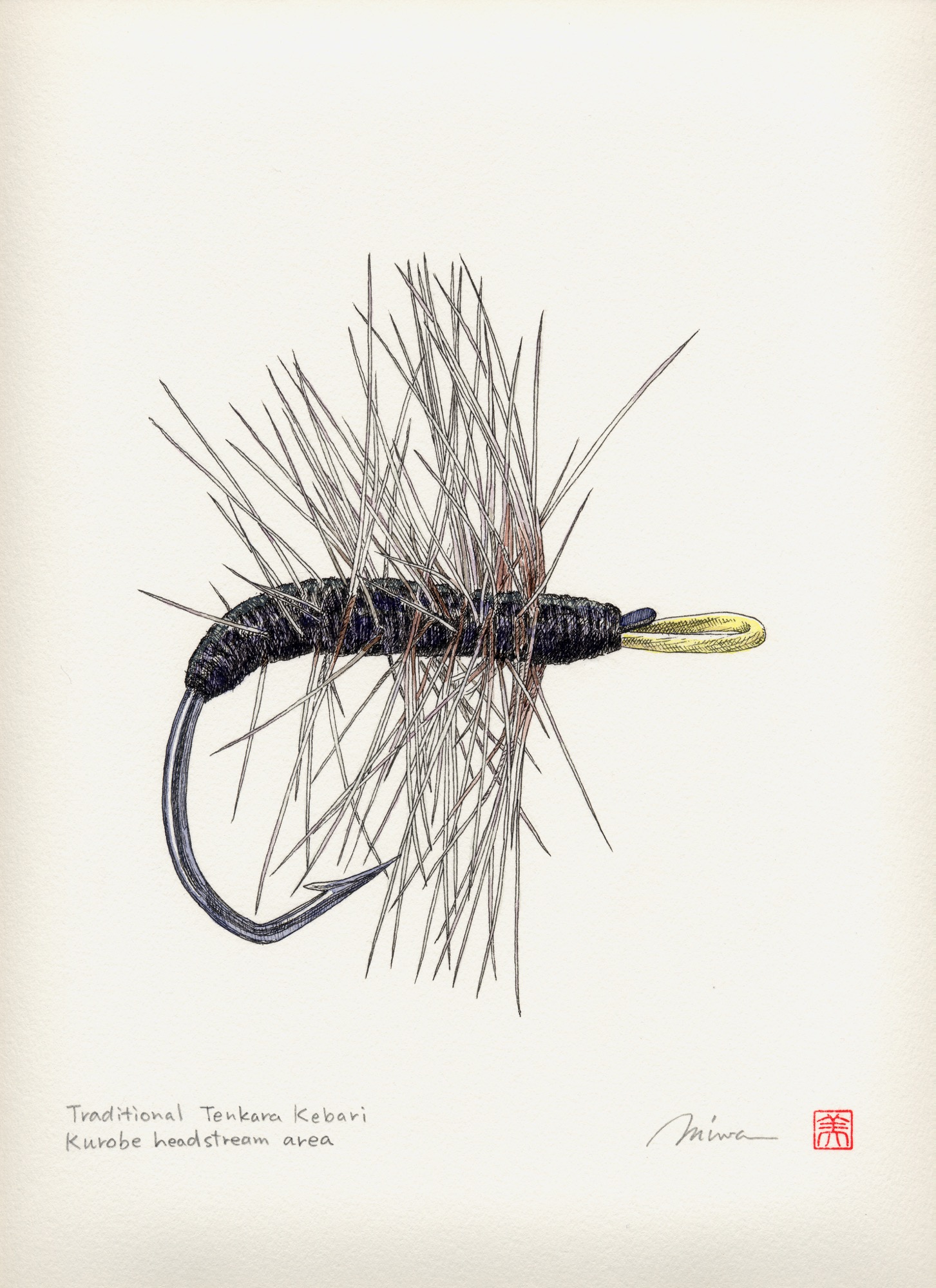

One main distinction separating tenkara from Western fly-fishing is its origin—tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes. While the West went to work designing fly patterns, weights, strike indicators, and other gadgets to control the reach of a fly or make the activity “easier,” the typical tenkara fishermen of today adhere to the original practitioners’ thrift and reliance on skill. At the risk of seeming irrational to a Western fly angler, most tenkara anglers rely on only one fly pattern, no matter where they fish or what is hatching. As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice.

"Tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes."

"As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice."

Ancient and mysterious origins

Tenkara felt like my own personal Machu Picchu. Here was a rich but hidden mountain culture relatively unknown to the West, so unpublicized that the coastal Japanese themselves only became more aware of it in the second half of the twentieth century. Although researchers can find numerous Western fly-fishing references going back as far as AD 200 or beyond, in Japan, records of the sport only travel back a few generations before disappearing into the forest along with the original, albeit illiterate, practitioners of tenkara.

Even the origin of the name, tenkara, is unknown. The phonetic reading of ten kara could give it the meaning of “from heaven.” However, the name is written in katakana characters, a Japanese syllabary mostly used for words of foreign or unknown origin. This leaves few clues but opens several theories on the original meaning of the word. The most common stems from the way a fly lands from a fish’s perspective, as if it were coming “from heaven.”

Until recently, in most parts of Japan, the method was referred to as kebari tsuri. Kebari means “haired hook” (artificially), and tsuri means “fishing.” In the late 1970s, as the Japanese rediscovered traditions such as tenkara that had flirted with extinction during periods of dramatic economic dislocation, a handful of tenkara enthusiasts began using the term tenkara exclusively to clearly differentiate the practice from other types of fly-fishing. Nowadays, in the appropriate context, it’s used to describe fly-fishing sans reel.

The adventure

I wasted no time getting to the mountains of Gifu prefecture, the region of Japan where tenkara possibly originated. Two friends from Tokyo met me at the airport, we loaded into a rented Nissan and immediately headed for the mountains. The suburbs of Tokyo sprawled endlessly on both ends of the city, a sea of lights with tiny rice paddies in lieu of backyards. Mountains on the horizon appeared impenetrable, abruptly bordering the suburbs as though the country were too small for foothills.

The seven-hour drive southwest was a bridge between two worlds, betraying how a mountain culture could have remained unexplored within a country the size of California. Traveling at sixty miles per hour I imagined how, just a hundred years ago, it would take a full day to cover what I did in ten minutes. I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years.

"I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years."

We arrived in Maze, a small mountain village of approximately 1,400 souls in the prefecture of Gifu. Kazuhiro Osaki, who goes by the name Rocky, and his wife, Ikumi, would host me during my stay. For several years, Rocky and his wife have managed the Mazegawa Fishing Center, a tourist center established on the banks of the Maze River to promote angling tourism and other activities in the area. Their home was quaint, my lodging a traditional tatami room with its typical grassy fragrance. A seat at the kitchen table provided a clear view of the mountains to the south. Being the monsoon season, sparse clouds frequently enveloped the mountains. I couldn’t have asked for a more scenic location or for better hosts—it felt like a dream.

Most mornings evolved into a pleasant routine of writing and taking care of the business side of Tenkara USA while drinking a cup of coffee and enjoying the mountain views. In the afternoons I visited the fishing center and tried to uncover the different layers of tenkara through fascinating interviews and encounters with individuals who made (and continue to make) its history. In the evenings, I’d try to fish the yumazume, loosely translated as the “evening activity period,” until it got too dark to see.

A living tradition

Perhaps the mountain culture of tenkara has always been too rich to ever really be at risk of true extinction. Talking to some early Japanese explorers of the tradition, I wonder how close Japan came to losing tenkara.

Eighty-nine-year-old Mr. Ishimaru Shotaro heard about my curiosities through the region’s social network. He came to the fishing center to meet this gaijin (foreigner) who was so interested in his tenkara. He guessed it was 1934 when he began watching a tenkara angler near his hometown of Hagiwara. He explained that approaching a stranger to ask about his techniques simply wasn’t done at the time. Keeping a subtle distance, Shotaro-san followed the angler for an entire summer, periodically going off on his own to try out the techniques he observed. This is how he learned tenkara, then taught others in the area, and is now often referred to as a tenkara meiji, or “tenkara master.” Without any records to prove otherwise, Shotaro-san may have been the rst tenkara teacher in the country.

I asked him why today’s young people think that fishing is difficult—despite the availability of books, magazines, and videos—even though Shotaro-san taught himself the practice simply through observation. He responded simply, “There were a lot more fish back then.” Mr. Shotaro described how at that time, when the damming of the rivers that accompanied Japan’s industrialization was far from complete, he often caught 100 fish a day, with a personal record of 150, numbers common and somehow sustainable among the professional tenkara anglers of the time.

“There were a lot more fish back then.”

When I met him, Shotaro-san couldn’t trust his body the way he did a decade earlier. His legs started giving out three years ago, and since that time, he had not visited the water. Nonetheless, one hour of talking about tenkara was just too much for him to bear. As he had done a hundred times in our conversation, every time he remembered a story about fishing and his youth, he smiled. But this smile was different. I could tell he wanted to fish again. In a very soft voice he turned to his nearby student and said, “Tsuri o shimashoo!”—“Let’s go shing!”

After helping him put on waders, his student and I assisted Mr. Shotaro into the waters of the Maze River. Mr. Shotaro said he wanted to fish with me, since he didn’t know if he’d ever have another chance. With a new vigor, his casting was fluid and precise, the manipulation of the fly enticing. In a stretch of river that had yielded few fish in the two months I was there, Shotaro-san got a fish to rise on his third cast.

Stolen technique

In the early 1960s, the practice of tenkara was as mysterious as it had been in the prewar period. Katsutoshi Amano, a name known to all Japanese tenkara practitioners, had to learn the sport exactly the same way Shotaro-san did before him. As Amano-san said, “Asking a man about his technique just wasn’t done at the time; I had to ‘steal’ the technique from him.” Ironically, given their age difference and the fact that both are from Hagiwara, there is a good chance the man Amano-san followed and mimicked was Shotaro-san himself.

Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, my principal tenkara teacher, and Mr. Amano were instrumental in popularizing tenkara among the Japanese starting in the late 1970s when Japan, at the height of its economic boom, began to rediscover itself and its traditions. In 1985, Japan’s largest TV network produced a segment on the sport, giving people throughout Japan an idea of what tenkara was about. Nowadays, newcomers can look it up online, watch videos, and choose from a collection of books and magazines that offer lessons on knots, flies, and techniques. A once-secretive practice that provided employment to landless peasants is now a source of fascination to urbanized Japanese and a growing number of participants in the United States and other countries.

Tenkara with a twist

Two months went by faster than the glimpse of a rising trout. But I was happy I had found the time to fish a little on a daily basis. My worst fear was that I’d end the journey wasting a lot of time and not “finding tenkara.” I feared my relatively reclusive nature would send me deep into the mountain streams searching for the soul of tenkara anglers from centuries ago, rather than seeking people who are alive and carrying on the tradition.

My fear of wasting time didn’t come true. I enjoyed incredible encounters with old masters, meetings with craftsmen, a very enjoyable time with my hosts and their friends, and a lot of fishing, too. But I also craved adventure.

The same isolation early tenkara fisherman enjoyed was a little more difficult to achieve in modern Japan. So we took to the challenge with canyoneering shoes, neoprene wetsuits, ropes, and harnesses, and our tenkara kit, mixing fishing with what is known as “shower-climbing,” a mix of canyoneering with climbing waterfalls. It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. Our portable gear didn’t add weight to our packs, and the telescopic rods could quickly be stowed away as we prepared to climb a waterfall. By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there.

"It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. ... By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there."

We set off on an expedition that took us to rugged tenkara-perfect mountain streams, far from the masses that leave many streams ravaged and devoid of fish. Out here, I finally felt the spirit of tenkara fishermen from eras gone by: They disappeared into the forests for weeks at a time, camping and fishing the streams, drying caught fish, and finally, when the catch threatened to be too heavy to carry out, headed back to the village markets.

We planned to build a fire by the river, where we would cook a trout “shioyaki-style”—only sea salt coating the skin, a firm branch serving as a skewer. And we would drink kotsuzake, a drink that, as I have come to appreciate, is underpinned with ceremonial and philosophical significance—though one shouldn’t picture a neat Japanese tea ceremony.

Kotsuzake is primitive and raw. Preparing and drinking it is an act of homage to the principle of not wasting the resources nature provides. After separating the bones from the meat, we placed them over the coals of the re to lightly roast and bring out oils and flavor, then immersed them into the warm sake. The result is sake with subtle and tantalizing fish flavors—all part of the Japanese mountain culture, and now a personal practice if I must eat a trout that I catch.

The cliff-hanger

Back on the treacherous, wet rock face, a small overhanging cluster of bamboo far to the left started to seem more reasonable the longer I clung immobilized by the waterfall. I normally would never trust plants to hold my weight over a fall that could potentially kill me, but at this point, adrenaline dictated my actions. I grabbed a bamboo stalk and slowly shifted the weight off my feet. I placed my trust in a root system that was out of sight under a thin veneer of soil. Through the patch of bamboo and other vines, I finally topped the cliff, beaming in relief. Under heavy rain, I wrapped an anchor rope around an ancient tree lying across the stream. When Futamura-san reached the top, he looked down at the pool below with a nervous smile and said, “Good job; difficult climb.” △