Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Peace Industry

Peace Industry began with a gift. In 1999, Dodd Raissnia bought his friend Melina, a painter and graphic designer fresh out of Chicago Art Institute, a little felt rug that he found in a craft shop in Tehran. When the pair became a couple, they wanted to build a business together. Melina, completely charmed and intrigued by this ancient craft, encouraged Dodd to take her to Iran to find more rugs. Their original idea was to import and sell them. But when they traveled to Tehran in 2001, they discovered there was not an ample supply of felt rugs available. The felting tradition, practiced by nomads for thousands of years, had almost entirely died out. Dodd and Melina decided to try to make their own rugs using Melina’s designs.

Dodd, a native of Tehran, found a local artisan who was able to produce Melina’s rug. This first piece was so well received that the couple was encouraged to go forward with their venture. Ultimately, Melina and Dodd outfitted a factory in Iran. They wanted to both expand and control the quality of the rug production. They began training local workers in the nearly lost art of producing felt rugs.

Through trial and error, constant research and innovation, Melina and Dodd arrived at a process that generated a durable, hard felt of high quality. Peace Industry rugs are made from carpet-grade lamb’s wool, which is plentiful in Iran. Dodd and Melina use a wool that is both tactilely appealing and wears well.

I spoke with Melina and Dodd in their Peace Industry showroom in San Francisco’s Mission District. Walking in, I was completely taken by the warm, engaging rugs with simple, modern designs. Melina’s shapes feel organic and natural, but also very clean. I was also taken with Melina and Dodd. Melina has wavy, dark brown hair and a big, magnetic smile. She frequently let out a deep, kind, outrageous laugh while sharing the story of Peace Industry with me. Dodd, tall and elegant, interjected and clarified periodically. They have been working and creating together for nearly twenty years and the comfort and ease between them is apparent.

AM Can you explain the felt making process?

MR In order to make a felt rug, you need a big floor with a drain and a large woven mat called the mother cloth. You arrange carded wool on top of the cloth and press it down with big, wooden forks. Then you sprinkle it with hot water. The rug keeps getting pressed down and walked on until you place another layer on top.

DR The pattern is made upside down. These women (showing me photos of felt makers from a century ago) are felting in the Turkoman region of Iran. They are rolling the rug and using the pressure of their arms to press it down.

MR That’s felting. And it’s still the same process - it’s the weight of people’s bodies.

DR The rug starts out almost twice as large and it is shrunk into the final size. But it doesn’t shrink perfectly. In order to keep the design you want, you have to constantly manipulate it, pull it, beat it, and sculpt it, so you are straightening the edge as it’s shrinking.

MR The edges of our rugs are all hand-rolled.

AM Can you talk about how the rugs are eco-friendly?

MR We don’t use any chemicals in the manufacturing process. We don’t put a backing on the rugs so you don’t need a rug pad. You just lay the rugs right on the floor. The only by-product of the process is dirty, sheepy water.

DR The sheep are raised the way they have been for thousands of years. They are mountain grazed and grass fed. We buy local wool directly from the shepherds.

MR It is all from neighboring villages within a 100-mile radius from the workshop.

AM How do you create the colors?

MR We use all the natural wool colors and we also blend them to create new colors. The fog (colorway) is white wool with a little bit of black. For the non-neutral colors, we dye the white wool.

AM Where do you get your design inspiration?

MR From my own work as a painter. I also draw inspiration from other textile designers and multidisciplinary artists. Ray Eames is a really big influence on me.

AM Can you tell me about the name Peace Industry?

MR Before we got into rugs, I had a business called Peace Flags out in Point Reyes. I was making screen printed T-shirts and peace flags with the same logo that we have now. The peace flags were a response to the Iraq war. It was a lot of fun. We also made really cute baby T-shirts and peace panties and it was paying the bills. Then we got into the rug side of our business and it just exploded. We had to change the name because we decided it’s not just peace flags anymore… it’s more than that. It’s an INDUSTRY. (Melina lets out one of her big, warm laughs.) AM Are you still working towards peace through your business?

MR Our business is normalizing the relationship between the U.S. and Iran in a very small, grassroots way. We run a workshop in Iran employing 30 people. We definitely intend to expand on that by doing collaborations with artists in Iran. That’s the best way for us to use our talents. I believe that developing personal relationships and friendships builds resilience and understanding that we all share one planet.

Rugs and Furniture in Felt

A warm and fuzzy curation by Boulder interior designer Jennifer Rhode

Felt has a longer history than people may know. It is considered to be the oldest known woolen textile. The Sumerians have myths about its origins, and several felt shops were discovered in ancient Pompeii. Today, felt is being revived as a construction material for modern furniture and accessories that are inherently warm.

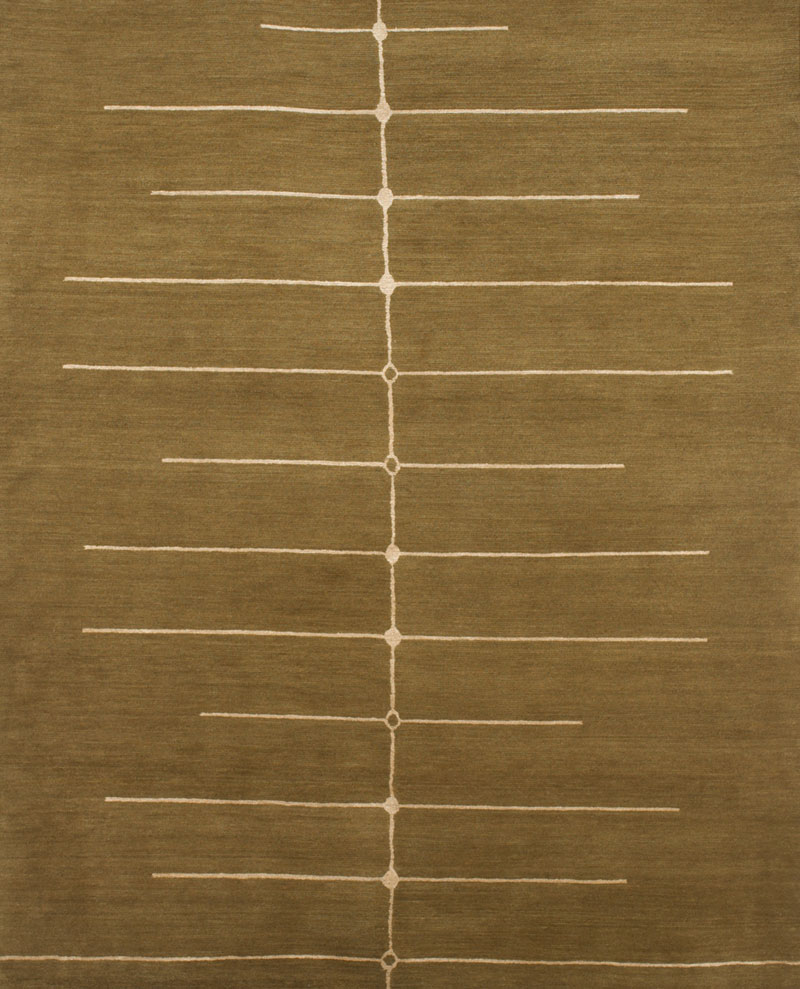

Rugs handmade in Iran

The felt of ancient Pompeii was created by matting and compressing wool fibers, and today’s felted rugs are produced in much the same way. The area rugs of Peace Industry are handmade in a workshop in Iran. The rugs are traditional in their time-honored production process, but the simple, geometric designs are thoroughly modern.

Braid pattern rug

The braided felt rugs of Angelo Rugs’ Highland Collection also celebrate heritage with the classical braid design, but the square, die-cut strand execution is crisp and fresh.

Colorful felt ball rugs

The felt ball rugs of Nepal resemble woolly marbles in a kaleidoscope of colors, stitched together. These whimsical rugs invite you to remove your shoes and engage.

Industrial felt rugs

Jim Zivic puts an industrial twist on both of his felt wool rug collections. For one, he attaches multiple colored felt panels with steel hinges, melding soft and mechanical. Zivic’s newest line features rugs created with felt strips linked together in random color ways, making each leather bound rug unique.

Die-cut bench

Felt is also being used to construct seating. The die-cut felt Joseph bench by Chris Ferebee is elegant in its simplicity, but exudes earnestness and warmth with its stacked, striped, woolen texture.

Felted chairs

The Felt Chairs by Ligne Roset are campy and sweet in their bright bubble gum colors, complemented by the clean, pared lines of the chair frame.

Coiled felt pouf

South African designer Ronel Jordaan’s Ndebele Chair is a circular, flexible seat created by stitching together a long felted wool coil. The serpentine design entices you to relax right into the center.

Felt stones

Stephanie Marin’s Living Stones are an unexpected contrast of soft, appealing textile and shape, depicting a natural element that is typically cold and hard. The stones beckon you to cuddle up and participate.

Felt Wall Art

The anodized, acoustic felt wall sculptures of Submaterial are creative collections of felt pieces arranged in colorful striped or geometric compositions—warm and modern.

Felted lamp shades

Outofstock’s pendant Stamp lamp and Tom Dixon’s Felt Floor Lamp surprise by using a thin layer of felt on their shades, providing both light and cozy comfort. Surely, the Sumerians would have appreciated such illumination when stamping out cuneiform on their clay tablets in the evening. △

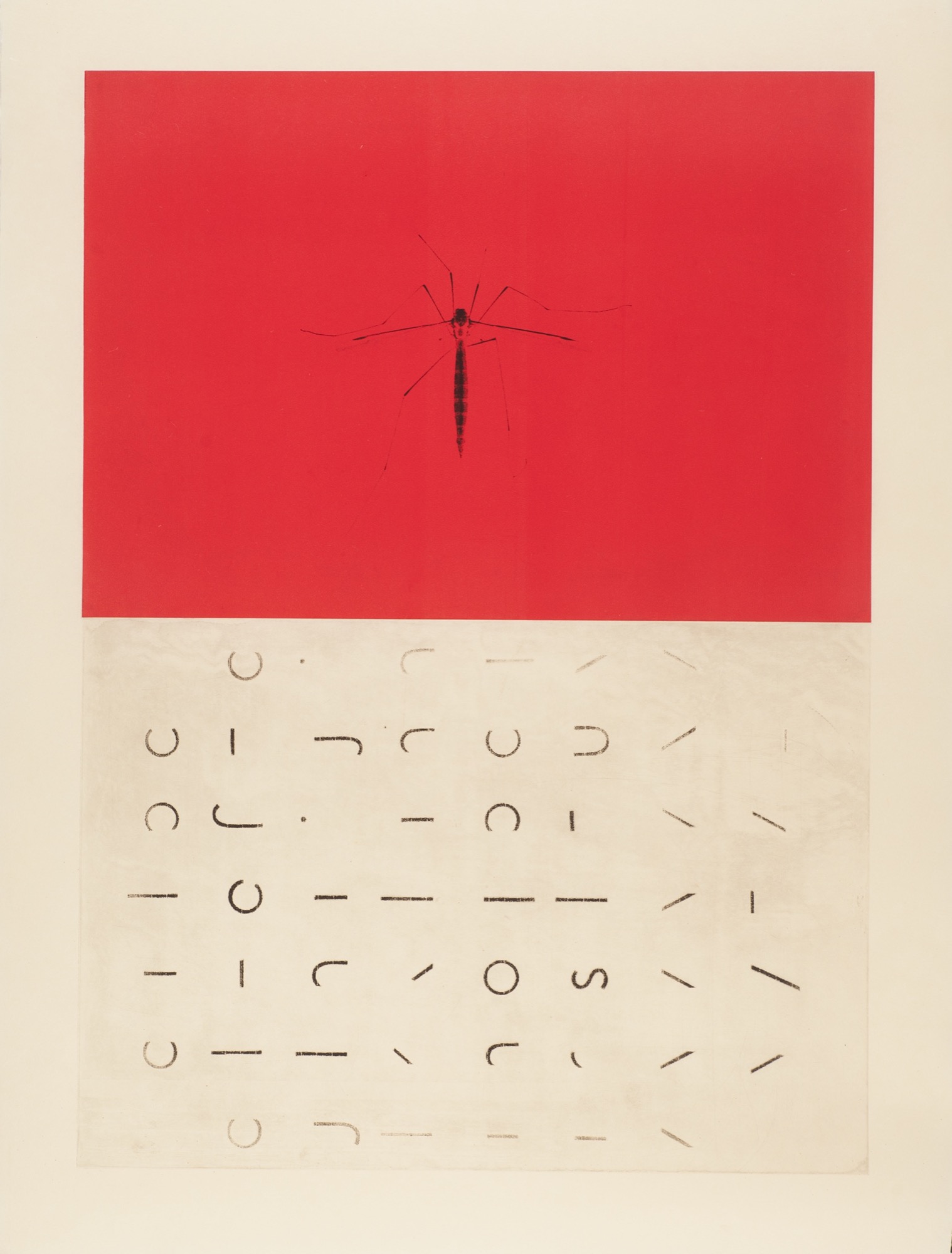

Growing Up Weese

The daughter a power couple of American modernism, artist Marcia Weese was born to design

Her parents are architect Harry Weese and pioneering design shop founder Kitty Baldwin. Born into a coterie of mid-century modern architecture and design icons—Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, and Charles and Ray Eames among them—artist and interior designer Marcia Weese carries on family tradition by designing modern rugs and creating fine art prints in her studio in the Colorado mountains.

I grew up on the near north side of Chicago near the lake. The endless horizon line, burning coal, bus fumes, beach sand, roller skates, sirens, frozen waves, thunderstorms, pigeons, dandelions ... Life in the inner city was complemented by summers in the country forty miles west. Crickets, lighting bugs, oaks, jays, owls, leaves, slugs, snake grass, otters, bluegills, cabbage butterflies, algae, sumacs, worms, Queen Anne’s lace, garter snakes, rabbits, clover, flies, bullfrogs ... I was lucky to dwell in both worlds. And each winter we spent the Christmas holiday in Aspen, and I fell in love with the Rocky Mountains, too. Streams, Indian paintbrush, marmots, boulders, puffballs, eagles, gentians, boiled wool, marzipan, scree fields, cumulus clouds, ravens, purple snow shadows, ermine, the smell of wet dirt...

The natural world has always been an oasis for me—a sanctuary, a place in which to marvel and explore. I borrow imagery from natural forms, weather patterns, textures, to bring a sense of balance to my world. My content often comes from the mystery and magnificence of nature—the perfect designer.

“My content often comes from the mystery and magnificence of nature—the perfect designer.”

Trained as a sculptor, I was attracted to site-specific work that often incorporated architectural elements. Printmaking was a natural antithesis to the rigor of planning and making sculpture, and as I look back, I have devoted most of my artistic life to works on paper. The ephemeral quality and the spontaneity speak to me. I am enchanted by the casual impermanence of a work on paper. And I am attracted to the minimal aesthetic, where I feel most comfortable. Less is more in my world.

“I am enchanted by the casual impermanence of a work on paper.”

As children, we would get the nod from mother that our father was coming home and it was time to "clear the decks.” All toys would be scooped up and hidden away so he could walk into a clean and serene environment. To this day, clutter confuses me and divesting is actually something I enjoy.

I moved to New York after art school to become the famous artist that is expected of all Bennington graduates. That was a nine-year lesson in humility and how to survive amid intense turmoil and fierce competition. I learned how to discern the excellent from the mediocre in art and design. I danced, made sculpture, painted, and longed for the horizon line. I found myself walking down the streets in Manhattan looking up at the rooftops. There, the sky silhouetted another cityscape of water turrets, parapets, and fire escapes. After nine years in New York, “Manhattanism” (i.e., "New York is the only place to live”), had gotten a problematic stronghold on me, so I escaped and returned to Chicago where I could breathe again. I loved walking along the lakeshore with the density of the city to the west and open water to the east.

I continued making art but asked my mother to teach me the ins and outs of the interior design profession so I could more readily support myself. She taught me well, and I have worked collaboratively with architects and clients across the country over a number of decades. As an interior designer with a classical modern bent, I was always searching for the quintessential modern rug to harmonize the room. I only found beige, beige, and beige or super graphic patterns that looked like bad paintings. Serendipitously, I was introduced to a family of Tibetan sisters, who knew the rug trade and had cousins in the business in Asia. This was a happy union, and for the past fifteen years I have worked directly with Tibetans who weave rug collections to my design in Nepal. Recalling visuals of growing up on the edge of Lake Michigan and the Midwestern prairie, to hiking the crags of the Rocky Mountains, my designs stem directly from my intersections with the natural world. The patterns and color palettes present an assemblage of modern but timeless rugs.

“As an interior designer with a classical modern bent, I was always searching for the quintessential modern rug to harmonize the room.”

When I eventually grew tired of Chicago’s pink skies at night and ached to see the milky way, I moved west to the Rockies.

Decades have passed, and the early modernists are still in vogue. Thankfully, this is beyond fickle fashion, which warms my heart as I feel I am surrounded by old friends and family. These days, when I encounter “everyday simple,” I pause and give thanks to my parents for teaching me that less is more. And I appreciate the efforts that are being made by those who are committed to good design and who are carrying on that noble tradition.

And I am ever grateful to have been handed the baton of creativity. It is an ongoing quest, one that continues to nourish, atop the peaks and in the valleys. △

“Decades have passed, and the early modernists are still in vogue. Thankfully, this is beyond fickle fashion, which warms my heart as I feel I am surrounded by old friends and family.”

Read "How American Modernism Came to the Mountains"—a memoir by Marcia Weese as the daughter to a power couple of early American modernism. Together with fellow members of Chicago’s design elite, Harry Weese and his wife, Kitty Baldwin, flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, bringing modern design and architecture to the Mountain West with them.