Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

My Source of Architecture

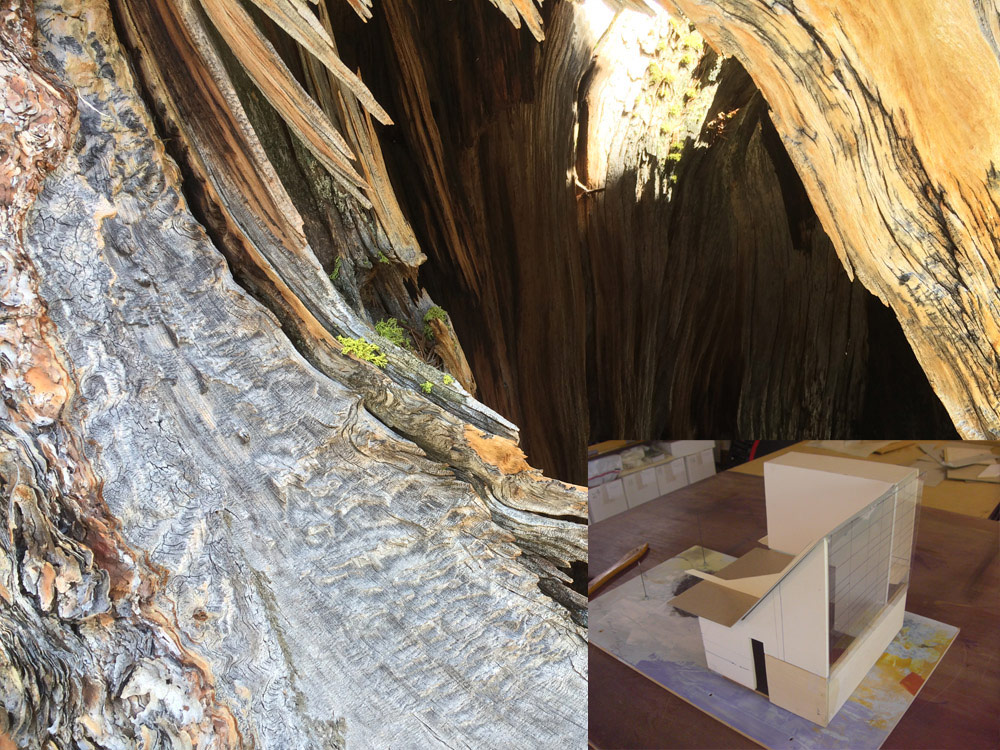

A structural impossibility impels Colorado architect ml Robles to deconstruct her design and rethink the source of architecture. Surrendering to the house’s revelation ignites a deeper means to practice her métier.

Our finite world evaporates every single day as the dusk we have learned to overlook withdraws the light and dissolves form, transforming the day to night. The infinity that is our universe begins to appear, one star at a time, until the lid of our blue atmosphere evaporates and we enter the continuum within which everything exists. In this big picture, the earth holds its finite position for only a blink. In that blink, we build, but it is in the infinite continuum that architecture is sourced; from there a vibrating intelligence strikes our ideas with intuition and inspires our thinking.

This is why some places make us feel so profoundly alive. I seek those places, I want to stand in spaces that make me fall to my emotional knees, I want to feel light pulsing through my veins, I want to be so profoundly anchored in place that time stops and space expands. I want that here, now. To get that, as an architect, I must look directly into the source and accept those unnamable vibrations that ignite intuition and spark inspiration. I must be willing to step into the unexplainable and know it is undeniable.

The power of constructing

My exploration into the source of architecture begins with a small group of deer, three, maybe four, that stood puzzling at the edge of the upturned earth where the craggy foothills’ belly lay gouged open under the pure blue Colorado sky. Violent excavation into the land is the first in a chain of aggressions made when we build. I was stunned silent when I came upon that small herd of deer staring into the gaping hole where waving grass had clung just hours before. The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning. Watching those deer reconsider that site was burned deeply into my architectural thinking, for that is what we architects do: We alter what was. This realization was one of my first steps into the source of architecture: Respect what exists.

"The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning."

Working with what is

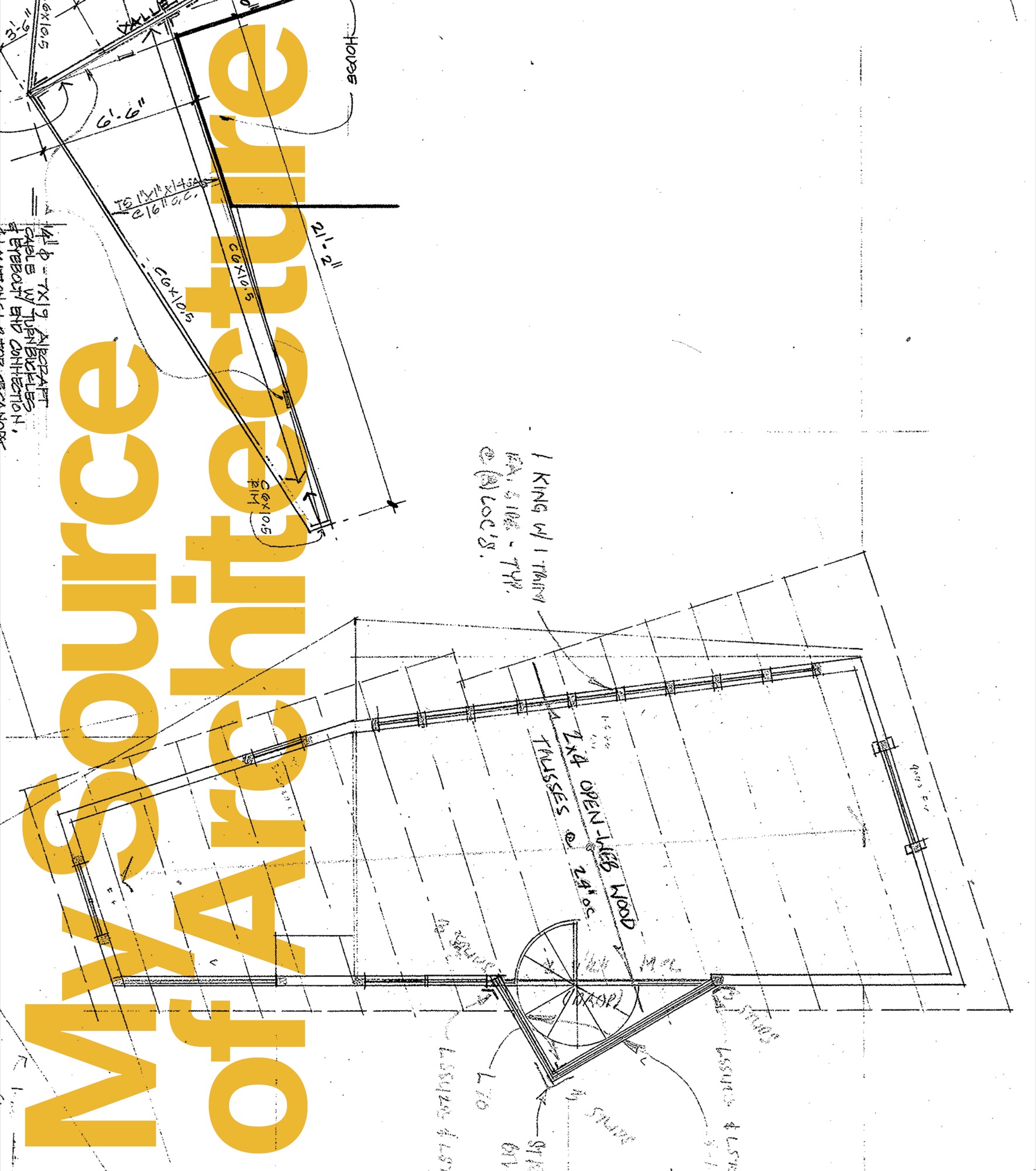

The small ranch house would have been a scrape-off to most sensible people. The builder and I, however, decided to work with the house and its detached garage, more from a perspective of “There is nothing wrong with its structure; let’s reuse it,” than any nod to its intrinsic qualities. The site was one of those hidden jewels in a nondescript part of Boulder, Colorado, that backed up to a parkway where the deep drainage ditch in front of the house made its way into a local watershed. Beyond that open area was a spectacularly clear view of the foothills curving along the horizon. I proceeded with designing a two-story, 3,500-square-foot (325-square-meter) house around, on top of, and including the existing ranch. It was all perfectly usual until the soils test, required to verify the capacity of the earth to carry the structural loads, said otherwise. The existing foundation would be unable to carry a second floor. The soils test is usually a nonevent, done for confirmation of what is already suspected rather than to dispute anything; this one, however, told us we needed a new foundation. We may as well have demolished the existing house since the newly recognized structural requirements were going to severely deconstruct the house.

Going up

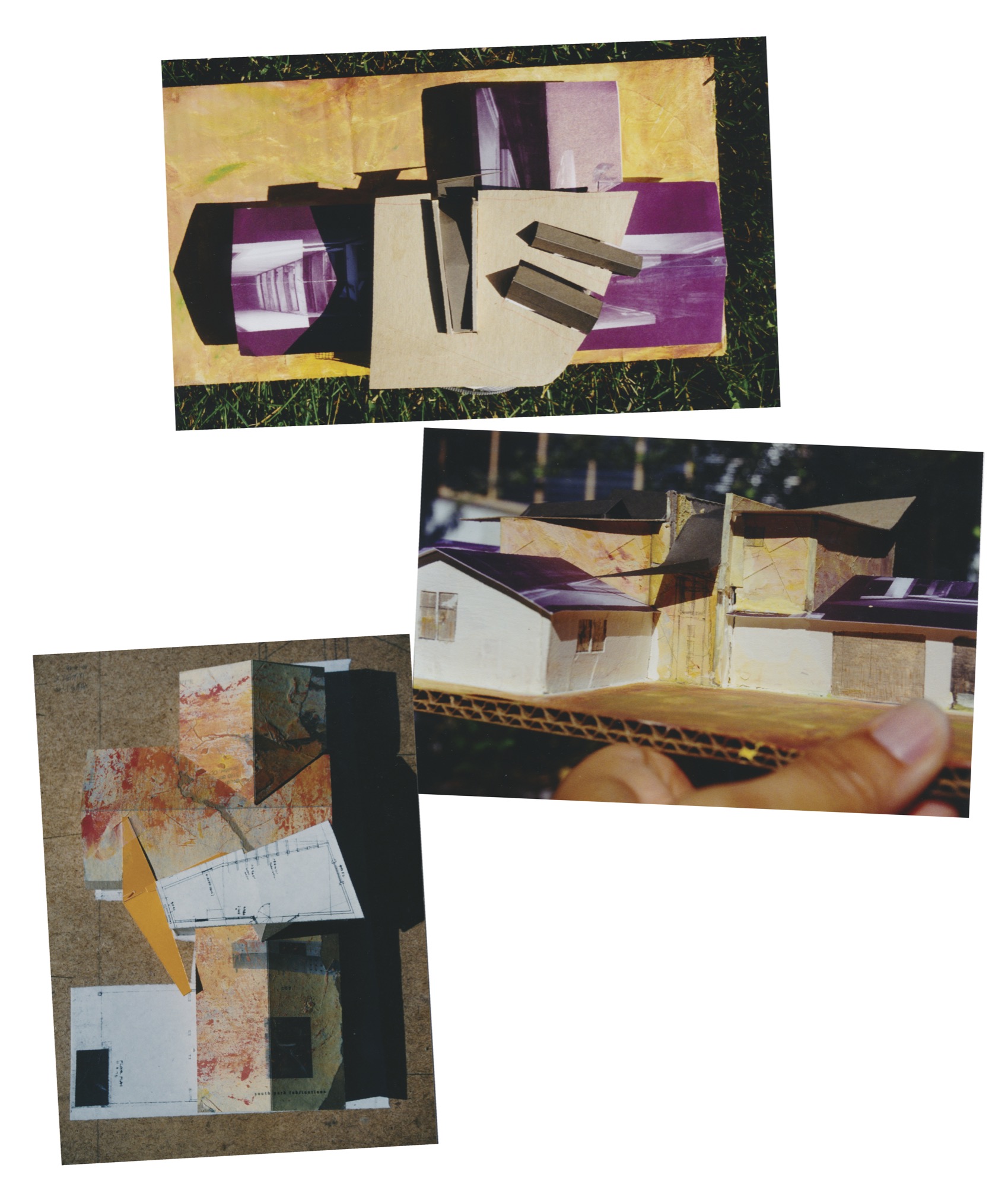

I sat with the cardboard model I had made of the house and garage. I had taped a collage of photos showing the magnificent view of the Flatirons—Boulder’s dramatic vertical rock-slab backdrop—onto the west edge of the model and was overcome by an insistence to build a second floor on that site to capture the view. Short of demolishing the existing house to build a proper foundation, I had to find another solution to going up. After wrangling with structural concepts, I sat down with my engineer and, using the model to illustrate, reasoned that if a tree could go up and out, why not a building? We would solve the problem by placing two piers between the house and garage to avoid disturbing the existing foundations, and then span back and front with steel beams to new foundation walls away from the existing structures. The framing spread over to the existing buildings, maintaining all the structural loads from the new construction to bear onto the two piers and new foundation walls. Like a gopher poking his head above the ground, the new two-story tower shot up from between the house and its garage structure with a spectacular 360-degree view.

We expanded the existing structure—both house and garage—to accommodate the new house with its tower shooting from the center. The only glitch was that the existing roof drained directly into the side of the new tower—a complete construction no-no, since the snow and rain draining off that roof into the side of the wall would eventually corrupt it. The standard way to deal with this is to build what is called a “cricket,” or hip roof, which is overframed on top of the existing roof at the wall intersection and stretches across it to lead water off to either side. This is what happens when construction creates a messy situation: The problem area is spirited away by trim false ceilings, overframing, and any number of other standard methods.

As I fiddled with that cricket roof on my model, imagining the tide of floodwaters raging against the tower wall, I became mesmerized by the idea of flowing water with its dancing light. What if we could experience that dancing light inside the house rather than scuttle it off the roof in obscurity? I was washed away with the inspired notion that we might be able to see this display of water.

What I resolved was to build a glass gutter—basically a slender inverted fold along that roof-wall intersection, furthermore sloping the whole thing to shed the water to the front of the house, right to the front door. I would capture the water in a big inverted wing that was anchored to the house roof on one side and flew into the sky on the other, creating a sheltering entry canopy. At the center seam, the low point of the inverted wing catching the water from the glass gutter, I sliced a gap and inserted a perforated sheet of weathering steel whose rust is managed in its composition. The rush of flowing water would fall through the perforations and drain into a gravel bed leading to the deep ditch along the front of the house. Mimicking nature, the water’s instinctive rush to the low point would be magnified, as in a waterfall with all its sparkling, glistening effect as it shoots to its destination. “You cannot build that,” they would say about the glass gutter. The big entry wing was less mystifying, and the weathering steel apparently not an issue at all as it was seen to be decoration.

Inspiration down the gutter (in a good way)

This would not be the first or last time I would hear those words, you cannot build that, but I could so clearly see the effect of the glass gutter on the inside of the house that there would be no turning back. Lucky for the house, the builder was also the owner, and he trusted the inspired gutter to deliver what was proposed. The house was built out with the kitchen spilling over into a dining area and outdoor patio and a living room with a face of windows articulating views of the Front Range—the eastern view of the Rockies. A see-through fireplace connected the living and dining rooms. Two bedrooms, a bathroom, and play area made the house family friendly. In the master suite, ceiling slots caught the glass-gutter reflections. A winding staircase led up to the tower room, which featured a sloping roof that jutted out to create shading overhangs for the wall of windows. We hosted an open house to celebrate the project and activated the glass gutter with a hose pouring onto the roof. Our “ship” launched with a cascade of water sheeting down the steel panel as the guests squealed with delight.

Over a decade later, I received an email from the latest owner of that house who had traced me through another house I had designed. This was the best house he had ever lived in, he wrote, and after living there, they discovered “wonderful, wonderful details,” such as the moonlight falling through the series of skylights.

When I read that note, I realized that I had never even considered the possibility of the moonlight casting onto that glass gutter and delivering itself through the ceiling slots. Astounding what shows up when unhindered inspiration leads to such unimaginable largesse. Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence.

"Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence."

Listen to what shows up

I have learned to embrace the marvelously unpredictable environment of design by working with physical models that take me out of my rational, calculating mind and drop me into an intuitive, three-dimensional state. Thanks to this project I got my second step into the source of architecture: Listen to what shows up. In this case the failed soils test and cricket roof changed what would have been an unremarkable construction into one that is able to lift the lid of our blue atmosphere and connect us to something so much bigger, something we might never have imagined, like the moonlight casting through the slots, awakening our senses and imaginations even more.

It is said that the dream is realized where the dream is sourced. If we do not dare to dream, to touch something within ourselves that ignites our passion, we will never see that dream realized. This certainly seems to be the case with places that make us feel fabulously alive—they touch something within us that we may have only known in dreams. And that is why, above all else, in the little blink we have on our finite earth, I am an architect. △

* * *

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently completing her first book in which she tells the story of how she came to be Under the Influence of Architecture.

Slow Architecture

Spawned by the slow food movement, slow architecture reflects a return to the roots of the master architect tradition

When Italy’s first McDonald’s poised to open in 1986—a stone’s throw from the fabled Spanish Steps in Rome, no less—it ignited not only a protest but a counter-revolution. Italians, so proud and protective of their exquisite centuries-old cuisine and culinary traditions, rebelled against not only the first McDonald’s in their iconic city but the decades of culinary collapse spawned by the “fast-food revolution” of the 1950s—that reduced food, along with its preparation and consumption, to its lowest common denominator. Political activist and journalist Carlo Petrini took part in the initial protest and is credited with the creation of the slow food movement. Three years later, in 1989, the manifesto of the International Slow Food Organization was signed in Paris by delegates from fifteen countries with the goal of promoting local foods and time-honored traditions of gastronomy and food production. It opposed fast food, industrial food production, and globalization, with the goal of preserving traditional and regional cuisine, and encouraging farming of plants, seeds, and livestock characteristic of the local ecosystem.

From slow food came the whole “slow” movement, with slow cities, slow living, slow travel, slow design, and slow architecture—a label credited to the Japanese.

“It is a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better. The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed. Savoring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them. Doing everything as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible. It’s about quality over quantity in everything from work to food to parenting,” writes Carl Honoré in his 2004 book In Praise of Slowness, which has become the new-millennium bible of the movement.

"The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed."

Environmental roots and “deep ecology”

So what is slow architecture? The Tvergastein Hut in the Hallingskarvet massif in Norway epitomizes the concept. It’s a simple wooden mountain cabin in harmony with its surroundings that took several years to build with appropriate, readily available local materials—think small carbon footprint. The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics.

A lifelong mountain climber and Norway’s most famous philosopher and a professor of philosophy at the University of Oslo, Arne Næss was influenced by the writings of seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher Spinoza and twentieth-century ecologist Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, the ground-breaking environmental science book published in 1960. Silent Spring documented pollution from the chemical industry and its detrimental effects on the environment, particularly birds, along with other negative human-caused environmental impacts. The book cartwheeled into scripture for the environmental movement of the 1960s.

Næss was convinced of the impending ecological disaster for planet Earth, and in 1969, he retired from his university position and built his Tvergastein Hut, where he lived and developed the philosophy of “deep ecology,” which sees the complex interconnection and web of all life-forms, objects, and events. Shallow ecology seeks solutions to economic problems through technological fixes; deep ecology demands fundamental economic, political, cultural—and spiritual—changes.

“It’s a whole different perspective of our place on Earth,” says Carolyn Strauss, a California-born, Columbia-educated architect who created the Amsterdam-based slowLab, a research platform for slow knowledge in design thinking and practice. “We work with individuals, architectural firms, architects, and students,” she says. “Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment. And understanding himself as one small part, and not a native of that ecosystem.

“It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things. We’re part of a much larger, complex system, which we can never fully understand. We tend to ignore that fact. And this leads to our fragmentation of the world, versus gestalt thinking—perception of the whole and interdependence. This type of human-centered thinking and fragmentation has generated a lot of the problems in the world,” Strauss says.

“[Arne] Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment....It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things.”

— Carolyn Strauss

Næss’s hut was built from 1937 to 1943, the pieces carried by horse and sled in sixty-two trips up the mountain. He also built a smaller climbing hut on the very edge of a cliff that required one to enter by climbing up through a trapdoor in the floor. Næss and his mountaineer companions climbed and dragged the planks and other materials up the mountain wall to build it. Næss died in 2009 at the age of 96. He lived at his cabin full time—this was no second home.

"The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics."

Spas and churches

On the opposite end of the slow-architecture spectrum is Therme Vals, a hotel/spa complex in Vals, Switzerland, built over the only thermal springs in the Graubünden canton. The architect was Peter Zumthor, who received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2009. Completed from 1993 to 1996, the building is made from stone taken from the mountain, plus concrete and glass. Designed to look like a cave or quarry-like structure, it has a turf roof and resembles the foundations of an archeological site, half buried into the hillside.

The locally quarried Valser quartzite was the driving inspiration for the design, and the building’s cladding is made from 60,000 one-meter-long thin slabs of the greenish-gray stone. Zumthor was fascinated by the mystic qualities of a world of stone within the mountain. He wanted to capture the light and darkness, the light reflections on the water and steam-saturated air, the unique acoustics of the bubbling water in a world of stone, the feeling of warm stones and naked skin—all to enhance the ritual of bathing. So that time would be suspended for those enjoying the baths, Zumthor wanted no clocks in the spa, but three months after the opening, he was pressured to install two small clocks. Zumthor carefully designed a path of circulation to lead bathers to certain predetermined points with areas and views to enjoy along the way. “The meander, as we call it, is a designed negative space between the blocks, a space that connects everything as it flows throughout the entire building, creating a peacefully pulsating rhythm. Moving around this space means making discoveries. You are walking as if in the woods. Everyone there is looking for a path of their own,” Zumthor explains.

A Spanish icon and UNESCO World Heritage Site, Barcelona’s extraterrestrial-looking Sagrada Familia basilica and Roman Catholic church is a classic and very literal example of slow architecture—still under construction 120 years after architect Antoni Gaudi first began it.

Urban and third-world slow architecture

Japan is among the leaders in slow architecture, and a renowned, award-winning example is Hillside Terrace in Tokyo’s trendy Daikanyama neighborhood. This internationally famous residential-commercial complex spanned three decades in its construction and evolution. Its creator, Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, was awarded the Prince of Wales Prize in Urban Design for reflecting the changes of time and giving life to the urban scenery. He also received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1993—a year after completion of Hillside Terrace.

“The flow of time can be measured against its diverse buildings and their relationship to the city of Tokyo as it grew to envelop them,” writes Maki. “The singular sense of place that people strolling among the various buildings and outdoor spaces of Hillside Terrace feel is no accident. It is the result of a deliberate design approach that has created continuous unfolding sequences of spaces and views, taking advantage of the site’s natural topography and, indeed, enhancing it with subtle shifts in the architectural ground plane.”

Butterfly houses

From the Norwegian Alps to the rainy highlands of northern Thailand, the architectural firm TYIN tegnestue, based in Trondheim, Norway, performs humanitarian aid through architecture. Their slogan is “architecture of necessity,” but that still embodies aesthetics. Started by five architect students from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, the firm’s third-world projects are financed by more than sixty Norwegian companies, as well as private contributions. TYIN has worked with planning and constructing small-scale projects in Thailand. “We aim to build strategic projects that can improve the lives for people in difficult situations. Through extensive collaboration with locals, and mutual learning, we hope that our projects can have an impact beyond the physical structures.” The architects use such readily available materials as old tires and locally grown bamboo.

“The Soe Ker Tie House is a blend between local skills and TYIN’s architectural knowledge. Because of their appearance, the buildings were named ‘The Butterfly Houses’ by the Karen workers [an ethnic group from southeast Myanmar]. The most prominent feature is the bamboo weaving technique, which was used on the side and back facades of the houses. The same technique can be found within the construction of the local houses and crafts. All of the bamboo was harvested within a few kilometres of the site,” write the architects on their website, tyinarchitects.com. “The majority of the inhabitants are Karen refugees, many of them children. These were the people we wanted to work for.” The architects hoped to foster a more sustainable building tradition for the Karen people in the future.

Form follows function

“Anybody who is practicing architecture right now, and has been practicing the last thirty years, has seen the profession become so much about style, form-making,” says Colorado architect ml Robles of Studio Points Architecture + Research in Boulder. “Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

“Form follows function,” was the mantra of twentieth-century “starchitect” Louis Sullivan, who admired Henry David Thoreau and Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80–70 BC), who said a structure must be solid, useful, and beautiful. Sullivan’s assistant was Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

— ml Robles

“You don’t start with the box and stuff everything in it,” says Robles, who explains that the three-dimensional modeling computer program SketchUp has become the fast food of architectural design for too many versus careful, thoughtful design.

“So much of what’s happened in the last thirty to forty years was about consumption,” says Robles. “What’s happened is that architecture has become a commodity. So you’ve got, sort of built in, this turnaround—anything that’s a style is going to be out of style...and that’s why we have the crazy environments that we have, and most people are so dissatisfied with their built environments. It’s because they have been designed for a little tiny space in time, with little regard for the past, or really, a long-term future. They’ve been designed for the moment.”

Given all that, Robles says, “Slow architecture, I think, was a pushback to architecture that was about a trend, a pushback to architecture or urban development that was about erasure, and it was a pushback to the commodification of interior finishes and furniture.”

Sustainability and sensibility

The other thing that happened, says Robles, was the sustainability movement, “which was trying to reground the built environment—to be responsible.” So there are LEED buildings, green buildings, and gold buildings. “I think what is happening—and slow architecture is illuminating this—the thoughtfulness of doing what architecture has always been doing is becoming important again. It’s kind of sad that that’s the way the profession has gone.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period. That those things now show up under a label is an interesting reflection of our time, in that we need to be reminded of what architecture is. Those of us who practice architecture in this way have always known.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period."

— ml Robles

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building; you’re in wonder, awe, you’re pulled through the space, usually by light, and you’re changed,” Robles says. “This happens to people when they go into cathedrals. Amazing places where people just, ‘Whoa.’ It happens when you go into a museum, or Union Station downtown in L.A., or Grand Central Station in New York. That’s the essence of slow architecture. What it does to the world. That’s what great architecture does. It causes you to pause and be present.” △

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building...that’s the essence of slow architecture.”

— ml Robles

Nature Is Architecture without Enclosure

Why Alpine Modern has a brief cameo in ml Robles' upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"

From my upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"...

So much of architecture is about replacing what exits. We remove buildings or parts of them, we scrape off land. We like new.

Then we get immensely attached to the buildings that have weathered throughout centuries. Think, Venice or historic buildings like Monticello or Westminster Cathedral. And we want to preserve them, not change a thing.

This is the discussion design enters into when we begin the critical examination of a project’s circumstances: What actually exists? Although the direction that is uncovered in the partí—the basic concept of an architectural design—holds both the physical and ephemeral, it is innumerate. Design, therefore, is a process of uncovering and illuminating the exact constructs necessary to meet the partí. And this is where the eye of the beholders produces the endless solutions to any given design problem. (Put another way, this is also where all hell breaks loose, for who is to say when a partí has been met?)

If architecture begins at the beginning of everything, and it is guided forth by secrets that cannot be told within the mind alone but are revealed by light, then it would seem that in order to uncover and illuminate the exact constructs necessary, design would have to continuously trace back to origin, to tapping the feeling that instantaneously shoots into the infinite.

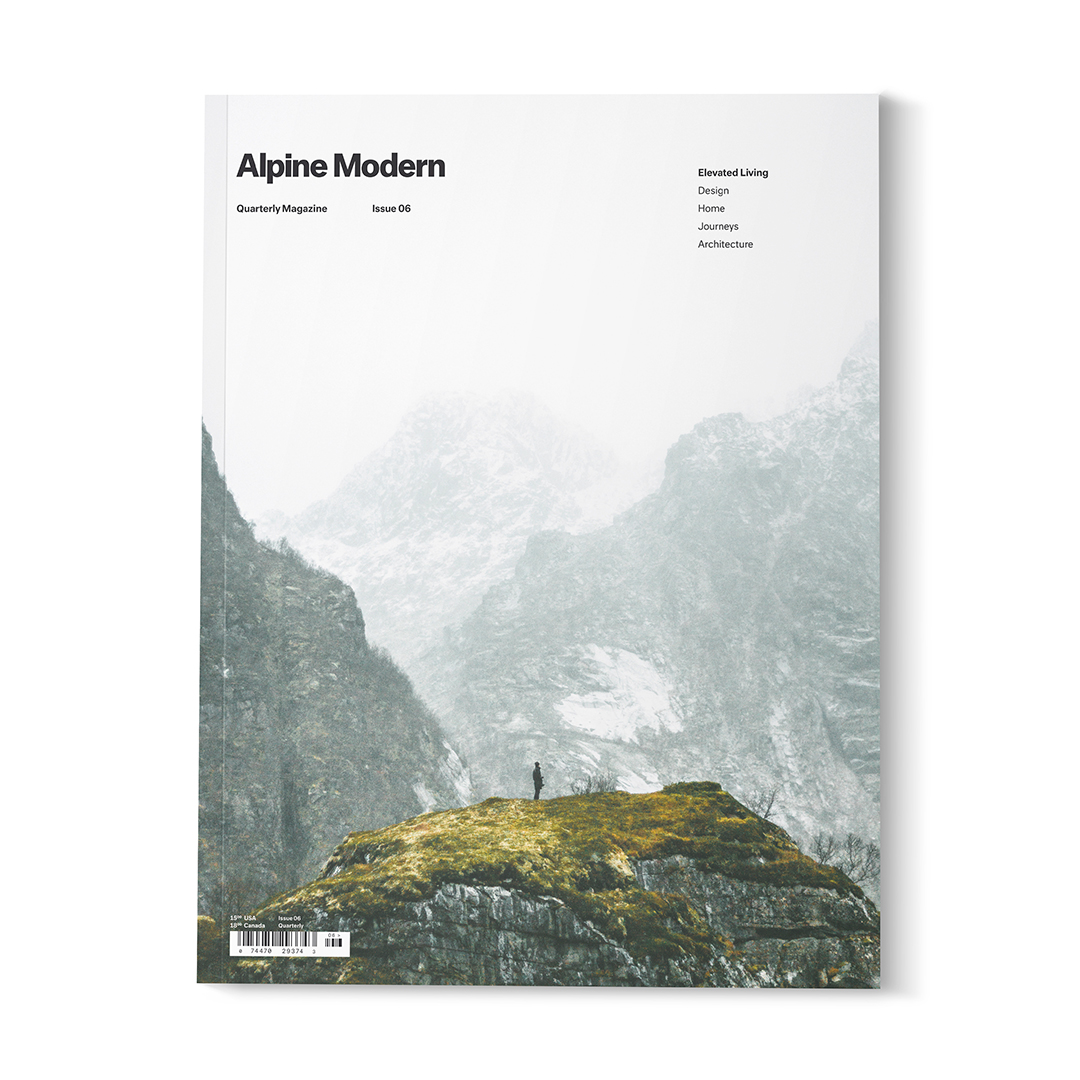

There is an image on the farewell cover of Alpine Modern’s print magazine. It is an image that fades from a near-white mountain backdrop to a dark silhouette of a lone person in profile standing on a mossy green capped rock. I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure. △

"I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure."

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently writing her book "Under the Influence of Architecture."