Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Minimalist Pottery in the Kyoto Mountains

An intimate visit with husband-and-wife pottery artists Momoko and Tetsuya Otani at their home and studio in Japan

The Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto departs not one minute late, travels almost 200 miles an hour, passes Mount Fuji on the way, and pulls into Kyoto’s vaulting modern station not one minute early. From there it’s 40 kilometers by car to Shigaraki, an industrial mountain town, where I’ve come to visit a ceramic artist whose work has transfixed me on Instagram for the past ten months.

Shigaraki is home to one of Japan’s “six old kilns.” The most admired pottery here—tea bowls and sake cups made from local iron-rich clay—is often misshapen and haphazardly glazed. Much is left to the felicitous violence of earth and fire in wood-fueled kilns. These clay items, used in the exquisitely calibrated tea ceremony, are prized for their imperfections, reflecting the wabi-sabi philosophy in which earthiness, transience, roughness and decay reveal the essential nature of the world.

Such is Japan: hyper-curated, thrillingly modern, clockwork precise—then offering you a tea bowl that seems primeval.

The ceramic artist I’ve come to see, however, is Tetsuya Otani, whose work departs so thoroughly from the Shigaraki style as to seem from another world. Otani’s hand-thrown porcelain chases the precision of machine manufacture. Its skin is smooth and naked, like that of a baby. I wanted to know why he was making such beautiful but plain stuff.

Right now, though, I have a few hours to kill, so I drive into the mountains to find the I.M. Pei-designed Miho Museum. The Miho is a kind of Japanese Getty, opened in 1997. It’s perched on a thick-forested mountain top like something a hermit might build if the hermit had several hundred million dollars. To reach it you walk through a hill via a gleaming, curving science-fiction-y pedestrian tunnel and emerge on a bridge that’s supported by a harp-string array of steel cables. The Miho was commissioned by an industrial-fortune heiress who also made time to found a sect in the 1970s, variously described as an art-centric religion and a sinister cult.

As traveler’s luck would have it, the museum is showing an astounding collection of ceramics by the 18th-century artist Ogata Kenzan, whose name means “northwest mountains.” His painted cups, bowls, and trays leave the viewer giddy, so varied and playful are they in style and form.

At home with Momoko and Tetsuya Otani

Five or so kilometers from the Miho is the home that Tetsuya Otani shares with his wife Momoko—also a gifted ceramic artist—and their three girls and a dog. It’s beautiful, with farmhouse mud walls and high wood beams that employ traditional temple joinery. Everything on the main floor revolves around the kitchen, which is far larger than usual in a Japanese house, reflecting the Otanis’ passion for communal cooking and eating with friends, many of whom also make pottery. The shelves, in the dining area and kitchen, are filled with both Tetsuya’s and Momoko’s pieces.

The work of Tetsuya Otani

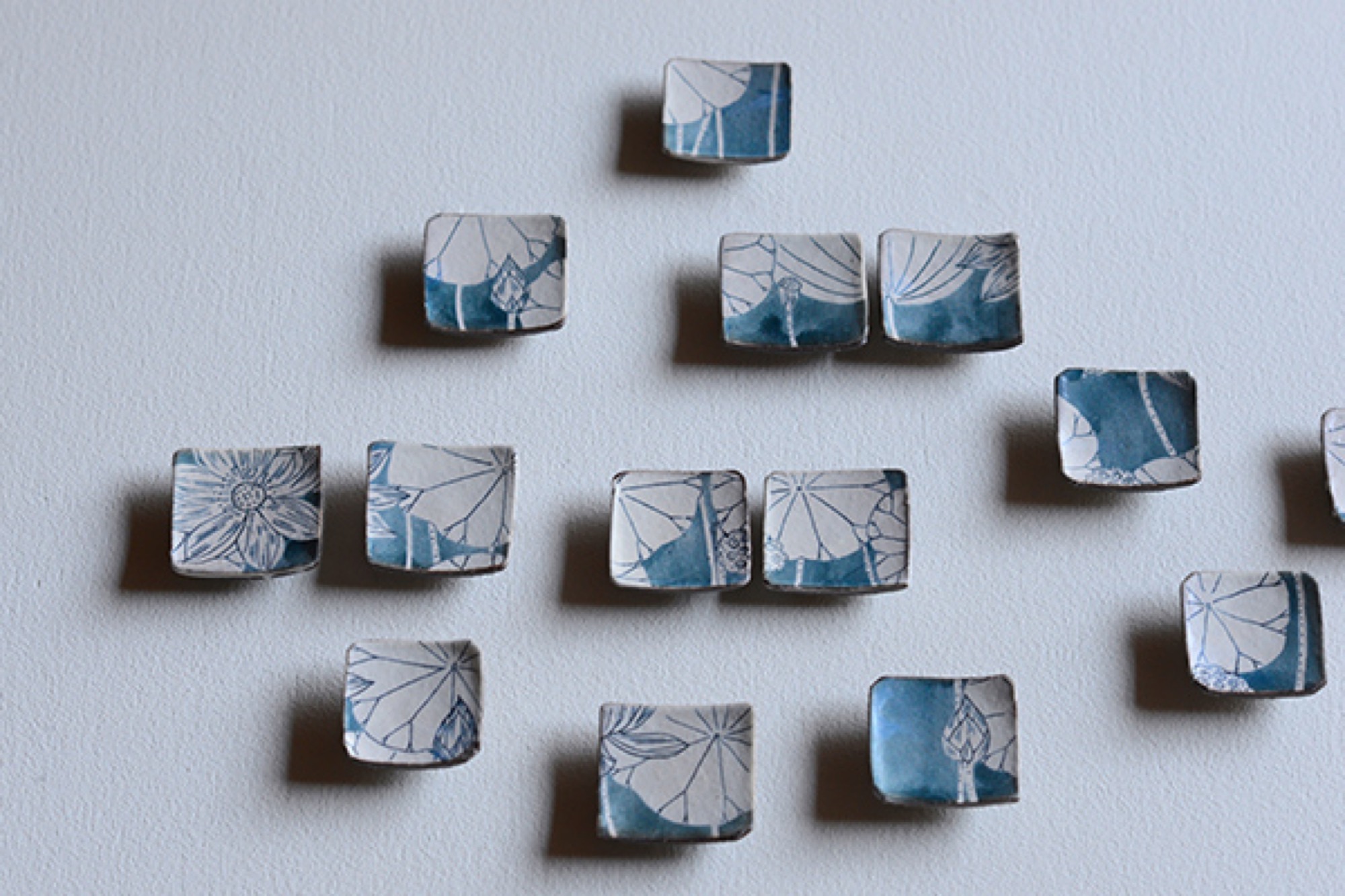

Lately attracting attention among collectors in Beijing, Shanghai, and Taiwan, Tetsuya shuns both wabi-sabi imperfection and Kenzan decorative exuberance. Everything he makes is to be used, mostly in the kitchen or at the table: tiny matcha urns with clinking lids, curved-belly flower vases, delicately spouted teapots, tiny soy dispensers, little round boxes. The pieces are finely lipped and polished to a supple smoothness; their creamy matte glaze begs to be caressed.

Tetsuya’s pottery has thrown off all temptation toward decoration. The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because “things that work give pleasure.”

"The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because 'things that work give pleasure.' ”

He studied in Kyoto, hoping to design cars, but when the economy skidded in the nineties, he shifted to graphics and ended up teaching product design (“how to make molds”) at the Ceramic Institute in Shigaraki, where he met Momoko and, on the side, learned throwing and glazing clay. By 2008, their house was built and he embarked on a ceramic career. He’s now in his late thirties.

I watch him work in the studio, which has wheels for him and Momoko, as he forms and pokes a bit of clay that will become a tiny strainer inside a teapot. A few feet away, a large machine mixes clay while sucking air from it, then extrudes large, irresistibly smooth noodles of the stuff. The machine is close to the same color as the clay. Tetsuya grins and admits he had it custom-painted to obliterate the standard industrial green. A clue to his fastidious brain.

The pure cup and the pure bowl

Later, we sit at the long kitchen table and look at bowls and cups and teapots and plates and discuss this idea of removing information from one’s work.

“The pure cup,” Tetsuya says, through Momoko’s translating, “and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

“The pure cup and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

One may begin with the form of a traditional Japanese offering bowl. Decorative motifs are removed until it approaches neutrality. Eventually you “come down to the point where we can use it on our table, not for the gods’ offerings.”

Momoko adds: “Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.” He produces smooth dinner plates as blank canvasses for food—altars, really. They’re used in fancy Osaka and Kyoto restaurants to showcase chef art. His works are unsigned, unmarked.

“Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.”

But cultural negation negates a specific culture, and Tetsuya says he has lately realized, when showing his works in China, that they are in some way indelibly, irreducibly Japanese. “I now feel that,” he says, “but I don’t have the answer yet about why I feel that way.”

The potter approaches, but never finds, ideal functionality. Tetsuya tweaks the ancient teacup form a wee bit from batch to batch, always seeking the right feel of cup in hand, the right curve of handle against thumb and finger. This lonely, incremental search for ideal form, endlessly repeated, is itself very Japanese.

The motivation is pleasure, however, not denial. Tetsuya and Momoko are exuberant foodies, and have found that their table-centric philosophy resonates globally through their gorgeous Instagram feeds, @otntty and @otnmmk, with more than 20,000 followers between the two for their pictures of utensils and food.

Tetsuya is also funny. He calls the clay mixing machine Mr. Hiroshira, “my only employee.” What about the beautiful industrial kiln in the next room, I ask? “No,” he says, “I work for it.”

Return to Kyoto

A few nights later, in Kyoto, my wife and I visit a little chocolatier and bakery called Assemblages Kakimoto, near the Imperial Palace. In the minimalist showroom up front I buy a box of orange biscuits enrobed in dark chocolate, each biscuit not much bigger than a postage stamp. Beyond the front space is a narrow, pretty room with a half-dozen seats or so against a counter, facing a tiny kitchen. We order chocolates and cakes and glasses of thirty-year-old palo cortado sherry. Two women to our right—the only other customers in the café—have come for the chef’s omakase dinner. With each course they look gobsmacked, enraptured by the treats placed in front of them. It’s beautiful food, for that is the Kyoto style. Each composition sits on the pale canvass of an Otani plate.

The entanglement of much fuss and no fuss that lies at the heart of many things Japanese is hard to describe, but when I palm one of the Otani pieces that we brought back from Japan, it seems to embody that contradiction. My favorite is a little round vase, the size of a tennis ball, whose satin smooth sides curve up to a sharp-lipped hole that’s big enough to accommodate the stem of a single bud. In weight and delicacy and touch and every other aspect the vase seems, to me, as close to perfect as it can get. It holds a lot of information about Japan. △

The Weavers of Lapua

More than a hundred years ago, the great-grandfather of Jaana Hjelt’s husband, Esko, opened a wool and felt boot factory in Lankilankoski, Finland, where the Ostrobothnian winters are freezing cold.

More than a hundred years ago, the great-grandfather of Jaana Hjelt’s husband, Esko, opened a wool and felt boot factory in Lankilankoski, Finland, where the Ostrobothnian winters are freezing cold.

Still in family hands, Lapuan Kankurit today values responsible and environment-friendly processes and pure natural materials. Multifunctionality of their products is important to owners and forth-generation weavers Jaana and Esko Hjelt. In their book, blankets can also be tablecloths or space dividers. Their high-quality textiles are made to bring beauty and happiness into a family's everyday life for generations.

Lapuan Kankurit's fine wool products weave together the story of Finnish handicraft traditions, innovative techniques, and the artwork of top Scandinavian designers. And so the legend continues.

A Conversation with Jaana Hjelt

Born: 1968 in Lapua, Finland.

Lives: After studying and working in other cities for ten years, I came back to Lapua.

Work: I do what I love. I run a weaving mill—Lapuan Kankurit (“Weavers of Lapua”)—with my husband, Esko.

Fun: I love to just stay at home with the children, to spend time without any timetables. But we all also love to travel and meet new people. That’s what I do for fun and for work!

Working on right now: Now it’s the “exhibition season,” which means traveling around Europe and attending fairs. It’s great to show our latest collection and hear the feedback.

Favorite place in the world: Home. This may sound boring, but because of my busy life as an entrepreneur, weekends at home are the best. Saturday evenings at home with family: good food, sauna, sitting, and talking with the kids about all the joys and sorrows of the past week.

Motto: Now it’s a perfect moment.

Inspiration: My husband, Esko. It’s great to have someone next to you who is seeking innovations. He always gets ideas for textiles, and we share the same passion to create something new and beautiful for homes. Together with our designers, we make a great team.

Treasured possession: My grandmother’s handcrafted textiles.

Never leaves the house without: A smile. What else do you need?

What’s next for Lapuan Kankurit: We also would like to expand a bit more from home textiles towards apparel . . . Our designers have already made some great bags. I just love them and can’t wait for production to start.

See the beautiful products Jaana and Esko Hjelt are weaving at lapuankankurit.fi. We also sell select Lapuan Kankurit products online and at the Alpine Modern Shop on Pearl Street in Boulder. △

The Building Friendship

Friends since preschool and sharing a love for design and the mountains, the founders of MTN Lab, an experimental furniture and art studio in Colorado, have always been building things together

Harris Hine and Rudy Unrau have been best friends since preschool. Now both 27 years old, they have founded MTN Lab, an experimental furniture and art studio in Colorado. Growing up in Boulder, Colorado, the lifelong friends have been building things together since they can remember—skis, bikes, random projects. But it wasn’t until spring 2015 that the idea for MTN Lab was born. Both back in Boulder, Hine and Unrau began showing sculptures at Studio Como in Denver’s RiNo art district at the time. “Getting in there is what really materialized the company,” Unrau recalls. “That’s when we came up with our name and went from just building stuff to actually focusing on a business.”

The two men, both quiet and reflective, share an ardent love for design and the mountains. Yet, they come together at MTN Lab—at the intersection of art and adventure—from opposite directions: Hine a trained designer and woodworker, Unrau a former professional mountain biker turned woodsman fighting wildfires for the Forest Service.

Harris Hine

Harris Hine grew up profoundly influenced by his father, Vienna-born modernist architect Harvey Hine, who founded HMH Architecture + Interiors in Boulder.

“I’ve always been torn between the design side of my personality and just wanting to be in the woods,” Hine shares. He went to school for design at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn before moving from New York City to Portland, Oregon, where he worked as industrial designer. “I didn’t find any fulfillment doing other people’s projects, and I didn’t really like the mass production side of product design,” he admits.

All those years, Hine pined for the woods, where his old friend was.

Rudy Unrau

Unrau, while attending college in Western Colorado, signed on with the United States Forest Service. “I was on track to becoming a smoke jumper, working for a helicopter crew down in Durango,” the long and lanky woodworker recounts. “It was a great setup because you work a ton in the summer, and then you get winter free to do whatever you want, like ski and move to Canada.”

Throughout those years, Unrau had been harboring the desire to return to making art. “Seeing the things you see when you get to fly around and travel the US and go to all of the mountain ranges... I had ideas emerge to work with the trees that had been burnt or partially burnt in fires because they get so twisted and cool.”

"I had ideas emerge to work with the trees that had been burnt or partially burnt in fires because they get so twisted and cool.”

Joint adventure up north

At last, one pivotal winter Hine and Unrau moved to British Columbia together to ski. Their close friendship and mutual influence would impact each man’s path. “Rudy was all in the woods,” Hine remembers, “Living together pulled him back into the design world and brought me back into the woods.”

Unrau agrees: “I’ve always been at home in the woods. Growing up, I really wanted to pursue mountain biking, so I raced mountain bikes professionally for quite a few years.” After the athlete got “a little bit tired” of mountain bike racing in world cups, he focused on skiing.

Skiing in Canada was good fun. Winter gone, however, Unrau planned to work another fire season. The outdoorsman envisioned himself carrying on that seasonal rhythm of demanding service and wild adventures in the snow for years until he had and his friend had their fill of youth and independence. “And... I crashed paragliding,” he tells, falling solemn all of a sudden. “I broke my back and almost died and spent half a year recovering.”

His loyal friend by his side, Unrau needed to reevaluate his future. “I realized, I wouldn’t be able to do fire again,” he says. “And then it was pretty natural the way MTN Lab came together—us getting our shop set up to where we could build.”

The MTN Lab process

Starting with sculptures, the duo soon began venturing into furniture. Their vision is to grow the Conifer studio into an art collective, with more creatives joining them. They are even planning to build a tiny house to accommodate visiting artists and designers.

MTN Lab is as much a concept as it is a company. “Our process is the most indicative of what we make,” Hine explains. The founders source all of their materials themselves in the Colorado mountains. “We quarry our own stones to carve and collect our own wood.” Like it was for generations of makers in the mountains before them, MTN Lab’s workflow follows nature’s rhythmic swing. “Right now it’s the season for us to go get river stones because the flow just came down,” Hine tells me, when I sit down with him and his partner on that warm day in early September. “And we are doing antler stuff because we found a bunch of Elk sheds. That’s this flow that we follow.” Adds Unrau: “Our company is trying to do the whole process from sourcing, getting our materials, designing it, building it ourselves, photographing it ourselves.”

The friend believes having grown up in the mountains is what motivates them to see the entire process through, from beginning to end. “Spending all of your free time in the backcountry—you’re just so inspired by what you’re surrounded by,” Unrau says. “Initially, we were out there to ski, climbing to ski. We were dirt-biking. But when you spend that much time out there, it altered our perception of why we were there. And now it’s awesome because we get to ski, but that’s not the whole part of the process. The ski is the vessel for finding the materials—as well as the inspiration.”

“The ski is the vessel for finding the materials—as well as the inspiration.”

Connecting nature and art

“I’ve always liked minimalist design, and I rarely see that done with natural materials,” Hine says. “You look at Bauhaus stuff, and it’s very industrialized. My dad being the modernist he is, half of me is always striving for that simplicity. But then there is the other part of me... the Colorado guy. And I see these cool pieces of wood and antlers and it naturally merged. In college, I was more on the industrial, clean-cut metal side of things, and my style has evolved more and more into a hybrid of rustic and modern.”

Unrau, for his part, never earned an art or design degree, nor does the lack of academic study in the field limit him in his current work. “We really do our designing when we’re out in the woods. We don’t sit down in an office to draw. We see the material, and the material almost dictates its design.”

They usually know right away, if a piece of wood they come upon in the forest will transform into an art sculpture, a table, or something else entirely. Back at the studio, they combine found pieces of wood or elk shed with marble and often with contrasting metal. The final artwork or furniture piece comes together like a collage. While the sculptures are never drawn out, the furniture generally is. “We design our table bases, draw them by hand. Sometimes, we bring it into CAD.”

The day I met up with Unrau and Hine, they had come down from their studio above 8000 feet to deliver a piece of art they made for the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. “We had this mobile,” Hine begins, chuckling, “And then Rudy dropped it on the staircase, and we were like ‘Oh, no, we’re so crushed. And we had to quickly build it a second time yesterday, and it came out eight times better than the first. That process isn’t always easy to rely on, but sometimes when you make it again, it’s better. This is how we continuously design.”

Speaking about the synergy between Colorado’s magnificent nature, rich history and tradition, and progressive modern art, Hine notes that he is profoundly influenced by the stone carvings of American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. “It’s that blend of leaving these big natural boulders and polishing one face of it.”

Rustic designs with wood and stone are ubiquitous. “But it’s hard to find someone who has done them simple enough so that these materials individually speak for themselves,” hine says. “Antler furniture is really something we have been experimenting with, because it’s hard to find a simple antler-anything. All the chandeliers are the same hunter antler cluster. And all of a sudden, you are appreciating the simplicity of the singular antler as a sculptural element. That’s what makes it alpine modern, and not just alpine.”

“And all of a sudden, you are appreciating the simplicity of the singular antler as a sculptural element. That’s what makes it alpine modern, and not just alpine.”

A modernists at heart, Hine still looks to the arts and crafts movement for inspiration. “Not stylistically but the whole concept of it is huge, especially since my education is in mass production and industrial design and product development. And going back to actually hand-building one-off pieces from the found materials we use, you can’t really build the same piece twice. It’s almost like we’re in an arts and crafts revival, which is weird for me because that’s the antithesis of the Bauhaus influence, of going from craft to industrial production.”

Our conversation later on reveals that the two 27 year olds are somewhat of an antithesis, too—to their fellow millennials. The Internet, they admit tittering, is their shortcoming. “Neither of us really enjoys social media, self promotion, or even doing the sales part,” Hine says. “It’s the cliché artist who doesn’t sell his stuff. We just are either in the woods or in the shop. It never feels like were working.”

MTN Lab projects

Each MTN Lab piece embodies a story of adventure and friendship.

For example, Unrau says seventy years ago, many trees were cut down to make room for high-voltage lines to Fairplay, south of Breckenridge, Colorado. “The company just left them, so these big old-growth rounds have been drying up there all these years,” he says. MTN Lab milled the pine rounds into table tops. “That’s our next big design push, designing bases for those tables,” he says. “Or the motorcycle, which is a lifelong dream we’ve shared since we were little kids.”

Indeed, Hine and Unrau want to build a motorcycle entirely from scratch, the back end made hand-carved in wood. Before winter, they even want to experiment with producing their our own steel, from mining the rock to crushing and melting it. Whether the resulting material will in fact be usable won’t matter as much: “At least we will be able to appreciate the process when we go to the store and buy steel.”

“The motorcycle is going to be very much like our furniture and our sculptures,” Unrau says. “I would describe it as an art bike. It’s going to be functional. It’s going to ride very well, but it’s not going to look like a conventional motorcycle. I don’t know if we’re going to be willing to sell it.” The business partners are also debating whether they will ever have the heart to sell the 1960s Airstream that once belonged to Unrau’s grandfather and they just finished restoring. “I never want to sell any of our stuff,” Unrau admits, laughing. “It’s hopeless.” △

Louis Joseph on Alpine Authenticity and an Old Sweater

An uplifting conversation with the founder of the Boston-based outdoor garment label Alps & Meters

Nostalgic and progressively technical at once, the rare outerwear garments of Boston-based Alps & Meters reflect an appreciation for the authentic alpine adventures founder Louis Joseph has experienced in mountain villages around the world.

AM Your idea to start a performance outerwear brand was inspired by a trip to Sweden and a vintage ski sweater. What’s the birth story of Alps & Meters?

LJ I’ve always been an alpine sports enthusiast, primarily skiing, and I’ve traveled the world to places near and far for it. I was on a trip to Sweden—could be as many as fifteen years ago now—and I bought a vintage knit ski sweater with very interesting technical attributes. Ever since that time, the garment traveled with me wherever I went. It became a significant conversation starter in places like New Zealand, the Rocky Mountains, Europe. I let a lot of these conversations wash over me and started to think more deeply about what was so interesting and appealing about that particular piece. That was probably the springboard for Alps & Meters, trying to understand what people responded to, from the romantic nature of that piece to its technical attributes, these beautiful, rich knitted fibers, which is a bit of an art now that is lost and forgotten. That sweater transports you to a different time and place, perhaps a little simpler. There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand.

"There is a truth woven into that garment I felt might give life to a brand."

AM Years of research and travel went into your product creation, until you finally found the right materials and manufacturers...

LJ Yes, I am probably five years into Alps & Meters now, since it was a spark of an idea in my mind. I took many trips to a lot of different destinations, here in the United States and in Asia, to find a factory that would work with a new brand, not only a small brand, but also try to innovate and create a different expression of performance outerwear. We came up with a product-creation philosophy that we call “forged performance.” It’s a marriage of classic garment construction techniques with natural materials, like whole-grain, water-repellent leathers and nano-coated yarns, and bundling that together with contemporary technology. Many factories found the complexity too difficult to digest. I ultimately found a family-owned company in Taiwan that has been knitting garments in a very sophisticated way for decades.

I was global director of strategy and innovation at Puma and actually moved to its headquarters in Germany. I left that job a couple of years ago, turned our website on to gauge a demand for the concept, and here we are.

AM What does your brand name—Alps & Meters—represent?

LJ We wanted to convey a sense of tradition and a classic appreciation for authentic alpine sports. Obviously, the Alps came to mind in terms of all their transportational values, and this very traditional, true atmosphere. The word meters has a double meaning within the context of our brand: meters not only in terms of height and the expansiveness of mountains and ranges, but meters is also the unit of measurement for tailors. We wanted to have that underlying meaning closely connected to the brand, because we are really trying to refine our garments and express a form of outerwear that’s very meticulous in terms of attention to detail and the materials we are using. This unit of measure helps us to think very creatively of tailoring the pieces in a manner that is not only differentiated but still provides first-class, on-mountain fit and protection. I always think of the old tailors’ measuring tape, that really rich, yellowed meter tape. And we love the ampersand in the brand name. “Alps & Meters” has a bit of an old-world family feeling to it that I think is nice and sturdy.

AM What makes you a mountain man at heart?

LJ I grew up skiing, primarily in the United States, and I fell in love with the sport— not only the sport’s individual aspect of being on your own in the mountains and having that quiet and connection to nature, but there was always a camaraderie and a friendliness about the places that I traveled to, where people can affiliate and relate, whether they are in Japan, Europe, South America. It always struck me that that same sensibility was shared and crossed generations. Before I got married, I spent a lot of my money on a couple of interesting ski adventures. I’ve skied in the summer, too. I’ve been to Argentina, and I’ve made my way to Chile. I always appreciated connecting with new cultures, primarily in mountain settings, and those simple double-chairlift rides, meeting somebody new, from a different background, a different place, speaking a different language.

It actually has always been a rite of passage and a tradition for the Alps & Meters team to ski a glacier at the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range. It’s about a four-hour hike with full pack, boots, skis. You start below the tree line, and all of a sudden you are in a snowy environment.

AM You have a deep connection to Vermont. Why did you open your office in Boston?

LJ My wife and I got married two years ago at a beautiful inn in Vermont. Much of the concept for Alps & Meters was born from ski trips to Vermont, sitting outside around a fire, snow falling, talking with staff who are avid skiers and alpine enthusiasts. We’ve tried a virtual headquarters in Vermont for some time, but the logistics were really challenging. Alps & Meters has deep roots here, but our team is now settling down in Boston, which is wonderful for logistical purposes, travel to Europe, shipping is very easy.

AM You strive for authenticity. How does this intent translate into your brand?

LJ There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else. That is something I love about European skiing, a timelessness and authenticity that crosses generations. It’s wonderful to hike the same trail, ski the same routes, or ride the same lift somebody had done fifty years ago.

At Alps & Meters, we are trying to express a very deep appreciation for classic alpine tradition, and that expression is obviously manifested in the products we are creating. The materials we are exploring are authentic. They are tried and true.

They have always stood the test of time. There are performance characteristics, but their aesthetic is very authentic, and they are a recall to that authentic experience. There is a great confidence in entities that are authentic, and they have a real gravity that can be felt. I’ve been to Chamonix, for example, and it just resonates with authenticity—the people, their respect for the mountains, how they treat one another. It’s one of those very difficult feelings to describe, but you know it when you see it.

“There is a truth: Authentic places, brands, and people are very comfortable in their own skin. They are not trying to be something else.”

AM You launched Alps & Meters with a small collection of three pieces. Talk about your flagship product, the men’s shawl-collar jacket.

LJ We are really trying to make a statement with this shawl-collar jacket and keep our exposure low in terms of the breadth of the product collection. The shawl-collar jacket is a very nostalgic piece from the perspective that it is actually a properly knitted garment. In today’s menswear world, there aren’t many factories or brands that are actually knitting goods. We wanted to revisit proper knitwear that’s protective, warm, has great range of motion and ergonomics, and apply that to an outerwear garment that has a contemporary stance. That type of classic garment construction technique was actually the first wind stopper. You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today. Leather is another material we feel has a very timeless nature. What’s special about that versus synthetics is that leather has always been used for maximum durability. It’s still probably one of the most durable materials you can find and apply if you are looking for garment reinforcement and protection. But what we find really intriguing is leather will wear in; it will take on patina in color, and nicks and scratches will become a memory keeper. You remember when the garment was marked a certain way, on a certain adventure.

“You turn the collar up, protect yourself from the wind. It surprises me that that isn’t utilized more within performance pieces manufactured today.”

We have since evolved, and we have six or seven pieces, including a beautiful alpine winter trouser this coming winter. In our next collection, we are also modeling an alpine anorak, a pullover, on a piece that was used by the 10th Mountain Division as a protective snow garment. We are making that from a British-milled impregnated, waxed cotton. It’s windproof, it’s water repellent, and it intrigued us from a performance point of view. Again, I’m surprised that such a highly durable, tactile, beautiful material that will also have interesting wear characteristics wasn’t being used in performance outerwear.

AM Your outerwear may evoke nostalgia in the older generation while appealing to younger winter sport enthusiasts for its performance aspects. Who is your target audience?

LJ When I was traveling in my old Swedish knitwear piece, the age range of individuals who felt my sleeve in the lift line or asked me about that piece was very diverse. We are still trying to learn where the intersection is of our forged-performance differentiation and the interest level, whether it is rational or emotional or a combination therein. We are feeling our way through the dark but are really trying to stay true to what we believe, which is a respect and appreciation for simple, timeless alpine tradition.

Personal Brief: Louis Joseph

Born

1973 in Santa Monica, California

Then What?

After a stint in California, my family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, then settled in Boston, Massachusetts— fittingly, during the Blizzard of 1978. I began skiing in the mountains of New England from a very young age. My earliest years on the slopes were spent in North Conway, New Hampshire, at mountains such as Cannon, Attitash, Cranmore, and Wildcat.

In my post-university years, I gravitated toward telemark skiing after having been intimately introduced to the tradition by a close Italian friend from the Dolomites of Italy.

Now Lives

Boston, Massachusetts, in a quaint area called the South End, a walkable, friendly neighborhood of side- walk restaurants, pubs, and coffee shops.

Lives With

I live with my wife, Vinita. She is my best friend and an adventurous spirit who shares my passion for the mountains and any sort of outdoor recreation.

Favorite Place in the World

My favorite place is to be fireside in an après-ski setting. I find no greater joy than exhausting myself skiing with friends and family and then reliving that shared experience through storytelling, a crackling fire, and the satisfaction that comes with a day well spent on the mountain.

Next Big Journey

My wife is Indian, and we hope to visit India together sometime over the course of the next eighteen months. One of our dreams for this trip is to extend the adventure to Nepal and visit the base camp of Mount Everest.

Life Philosophy

Philosophically, I’m hopeful that I am leading a life in which I have my eyes open to new experiences, a sense of adventure, stay firmly grounded with humble perspective, and express a constant thankfulness for the opportunities afforded me while being kind, considerate, and helpful to those less fortunate.

Favorite Piece of Clothing

I appreciate clothes and equipment that are timeless in their utility and presentation. Therefore, my favorite piece of clothing is my father’s official U.S.-issued peacoat, which he wore while serving in the Coast Guard in the 1950s. Made from heavy boiled wool with a uniquely high collar, this jacket’s cut and sewn simplicity belies a warmth, durability, and protective nature that rivals contemporary outerwear of today. It’s also a powerful memory keeper as my father’s name, military company, initials, and year of issue are scratched on the interior in indelible chalk. When I’m not wearing my Alps & Meters shawl collar jacket, my father’s peacoat keeps me timelessly stylish and warm because of its deep family connection.

Inspired By

My mother and father have been my greatest influence and have been a well of inspiration to me throughout my life. My father is a first-generation American who instilled in me a strong work ethic and a “can-do” mentality. My mother is full of humor, mischief, and adventure, and I thank her every day for teaching me to ski. Their combination of values, imagination, and powerful encouragement have inspired me to follow my passions and, without a doubt, set me on a trajectory to explore, create, and launch Alps & Meters. △

Title photo by Torkil Stavdal

Makers on Board

Born out of passion for the ride, handcrafted snowboards, splitboards, and skis by Vancouver Island's Kindred Snowboards feature marquetry artwork.

Kindred Snowboards was born out of passion for the ride and the opportunity to grab a snowboard press off Craigslist. Meet the spirited couple who handcrafts custom snowboards, splitboards, and skis featuring marquetry artwork on Vancouver Island.

Evan Fair and Angie Farquharson have been designing and making custom snowboards and skis together in their backyard woodshop on Vancouver Island since 2010. We squeeze in a weekend visit just before the busy winter season to get a glimpse into their craft, their art, and their humble lifestyle in a rural community on the island’s east side. The couple built the Kindred Snowboards brand from scratch. They cultivated the low-impact operation out of nothing more than a passion for the ride and the desire to make a higher-quality product—yet without any background in fabrication.

Beautiful Comox Valley and Mount Washington straddle this area fifteen miles (twenty-four kilometers) north of Courtenay, British Columbia, where their home and shop are located. Weather on the east side of the island is mild and temperate year-round, a surprise given the substantial annual snowfall in the nearby mountains. The couple’s home sits at sea level in a forest, the mountains hidden from view. Land plots are large here, spreading neighbors apart. Industry in this area is a miscellany, though mostly milling timber and small-batch farming. Neighborhood homesteading makes the community largely self-sufficient—the local crops and dairy products go directly to the local population.

Pressed to jump

“How is a snowboard made?” the couple, both in their late twenties, asked each other one day before it all began. Not long after they pondered the process it may take to create the boards their life revolves around, a snowboard press came for sale on Craigslist. Fair and Farquharson, as adventurous as they are curious, grasped the opportunity. At the time, they were living out of a camper van and chasing the best snow to ride. But they made the purchase, hoping the investment would be the impetus to launch them into a more serious endeavor.

They were committed. Being avid riders themselves, they knew exactly what they wanted in a board, what their ideal board would look like, feel like. So they learned and improved upon the techniques to make a better product. Their goal was to create high-performance boards and skis that enhance, not hamper, the user’s skill, style, and fun on the snow.

“Some experienced riders know exactly what they want, down to the numbers,” Farquharson says. With others, the Canadian gear artisans spend significant time getting to know the customer’s riding style and preferences. “For the topsheet artwork the questions are a bit more ephemeral,” she says. People have asked for anything from the silhouettes of their favorite mountain to portraits of their pets or pop-culture idol, and even memorials to lost loved ones. Kindred’s Limited Edition Series, on the other hand, features artwork infused with an alpine or coastal sensibility. “I draw from my own personal experiences in nature, as it is common ground for people who spend their recreation time outdoors,” Farquharson says.

“For most people the way their gear looks is a very close second to how it rides,” she knows from experience. “People who go for a custom build impact the end product directly, which can be empowering. The ride becomes a distilled reflection of the rider and what they want out of their alpine experiences. In the end, Evan and I hope our work inspires people to be themselves and to be better riders.”

“People who go for a custom build impact the end product directly, which can be empowering.”

Shop talk

That mission to make a superior board hasn’t shifted or been compromised in the five years since Kindred began. Each board is treated with the same intense amount of care and precision. Personal connection with each customer and hands-on craftsmanship that goes into every board leave the couple remembering almost every individual product. The number of orders Kindred fulfills has been growing every year. By the end of this season, they are projecting to have made approximately 150 boards, splits, and skis.

Their search for the right place for Kindred led the couple to a tree-lined rural spot with a woodshop, old smokehouse, and former boathouse turned into a woodshed. They purchased the property with the intent to grow their business and live in the same place. “At first, we considered commercial property around the area, but it made more sense to have a shop very close to home,” says Fair. “The former owner was a cabinetmaker, so the shop already existed and was set up for woodworking.”

"Personal connection with each customer and hands-on craftsmanship with every board they make leave Fair and Farquharson remembering almost every individual product."

Sunlight filters into the shop through the grapevines that walk along the top of the awnings and the edge of the roof. As the gentle breeze blows, the leaves dance in the wind, making the patches of light dance on the floor. The view from the workshop doors is still lush and green this time of year; an occasional chicken races by or stops to graze for bugs in the grass. Inside, the walls are neatly laced with deliberately arranged hand tools and jars of screws and nails hanging from lids nailed to the shelves, organized according to the makers’ workflow. Fair’s homemade shelves display boards and skis in progress. It’s obvious the two designed this workshop with careful thought.

Fair puts on an album by Little Feat as the machines are slowly starting up. All of us pull on protective face masks before he begins sanding the core of a board he prepped the night before.

Meanwhile, at the giant table in the back of the shop, Farquharson sets up the topsheet, the piece that is most visibly “Kindred” to those familiar with the distinctive snowboards. The topsheet, a thin wood veneer, is intricately designed. The decorative patterns and graphics are meticulously cut from different woods and inlaid using a technique called marquetry. Defined by the grain and color of the woods, the outline of a fir tree begins to show light and definition in its branches, and a moon shows its craters. This detailed, time-intensive process makes Kindred boards one-of-a-kind art pieces.

Farquharson cuts the wood with her penknife. We talk about Kindred’s customer base as she carves out a moon from a delicate sheet of gorgeous black walnut.

“We’ve had incredibly strong local support from shops and individuals, but we are fortunate to ship all around the world,” she says. “We even had a Japanese fellow arrive unannounced from the other side of the world who had planned his whole vacation around watching our build process...He is now a friend of ours.”

Return to the Valley

Fair sets up a bottom sheet to be cut with a drag knife mounted to a CNC machine (computer numerical control machine, or automated milling machine used to make industrial components). He tinkers with the calibration on a laptop next to it. Satisfied, he hits “start” and the knife begins to cut out the Kindred logo from the sheet. When I ask him about their initial business ideas and how things have developed through the years, he pauses. “Humble beginnings for sure,” he replies.

“The concept was founded while we were living in a truck and camper. We had left the island to travel throughout Alberta and BC looking for the next ski resort. When we decided to embark upon the snowboard-building adventure, we returned to the Comox Valley, where we already had a network of support. We initially saw a potential niche in building high-quality North American skis and snowboards, and quality and beauty remain central to every step of the process—no cutting corners.”

A complex custom build can take the two up to thirty work hours to design and build a board or a pair of skis, not counting drying and curing time. The Limited Edition Series builds, where Kindred makes a small number of products with similar designs, still take up to fifteen hours each.

The day goes by quickly, and before we know it, the afternoon sun starts to set. The board is ready for the nal press, and all the layers are assembled with a chemical-free epoxy slathered on between each layer as the machine applies a healthy dose of heat and pressure. It’s fascinating to watch the steel tube stock apply pressure, making the epoxy ooze out the sides, slowly creating mountains on the floor. The snowboard press that started the whole operation is beautiful in its frugality—a testament to Kindred’s mindset.

"We initially saw a potential niche in building high-quality North American skis and snowboards, and quality and beauty remain central to every step of the process—no cutting corners.”

Community board

A couple of miles from the workshop, a local mill saws logs into lumber for the core pieces, the main foundation and center of each board, sandwiched between layers of fiberglass and carbon fiber. Farquharson and Fair know the owners of the mill well, and the family’s son is out working when we visit. With a population this small there is a strong reliance on others and an understanding that you are a connected member of the island community. Your actions greatly impact the local environment and its residents. Thus, good relationships with neighbors are important for businesses like Kindred to thrive.

As we observe the milling, Fair steps in to help move the last few logs on the run. “Many people are here for recreation—not specifically to ski or snowboard—they come to enjoy a work-life balance and the mild climate, fostering a slower pace overall,” he tells us.

What’s in a name?

How did the name “Kindred” originate? “We wanted to recognize how constantly blown away we are by the support of our community, friends, and family,” says Farquharson. “On another level, we give homage to the incredible relationships that are forged through alpine winter sports and lifestyle. Nothing quite compares to charging through fresh snow engulfed by the euphoric hoots and hollers of your friends. Those snowy moments, when we’re living a shared experience, feel like pure magic. When you are surrounded by people who embody that joy on and off the snow, you can’t help but feel like family. Those are our people. Kindred felt genuine and accessible, as we were sure that other skiers and snowboarders could relate.” △

Window to South Tyrol

An artist and sculptor returns home to South Tyrol to converts an old farmhouse

Artist and sculptor Othmar Prenner converts an old farmhouse in the mountains of his native South Tyrol and realizes his vision of an alpine dream home—between craftsman tradition and modern art.

Othmar Prenner lounges by the spectacular panorama window, looking out into the pristine nature of South Tyrol. Modern fiberglass lines allow him to work up here, straight across from the massive, snow-capped peaks of Italy’s Vinschgau.

Technology and nature don’t contradict one another, if you ask the artist and sculptor. On the contrary. The Internet enables him to be in nature while developing new art projects and designing furniture and objects made of wood.

It is here, in his native South Tyrol, that Prenner found his way back to his craft and rediscovered the joy of creating something new with his own hands.

Every corner of his remodeled farmhouse, completed in 2011 and internationally published more than twenty times, is filled with tools, paintings, finished and unfinished pieces of furniture, and all sorts of arts and crafts. The home is vivid, and it’s cozy in front of the black steel fireplace—a focal point—suspended from the ceiling. Othmar Prenner loves the open flames, the feeling of sitting by a campfire in his living room. He dismisses ovens with glass doors and generally has his own and very clear ideas about architecture and interior design.

He helped build an atelier and gallery near Zurich, Switzerland. “I only do things I like 100 percent,” Prenner says. “That’s why I’m not interested in collaborating on big projects, where you have to make 1000 compromises.”

This was far from the case with his very personal project, the mountain retreat at home in South Tyrol. Here, the almost fifty year old was able to realize his design vision one to one and create a refuge that meanwhile has become his primary residence and studio. Rarely does he drive back to his apartment in Munich these days. “I never thought I would leave the city. I’ve lived there for twenty-two years,” he says. “My focus is here now. I love living in nature and don’t need the city.”

“My focus is here now. I love living in nature and don’t need the city.”

Art in the city, craft in the country

Prenner bought the old house in his native region near Mals twenty-five years ago. The property is part of a small hamlet that is still being farmed in a steep valley on the Reschen Pass near where Prenner grew up. In his stube, which is nontraditionally located on the second floor and combines the kitchen and dining room, he tells me he spent many childhood hours carving wood and that he has always wanted to become a sculptor since he was a young boy. His parents had little understanding for his artistic ambitions but agreed to a cabinetmaker apprenticeship. Prenner strived for more and afterward studied in Innsbruck and later in Munich. Today, his calling has become his profession, a mix of sculpture and designing furniture and objects for the home. “During my Munich years, it was definitely the arts, now I’m balancing both,” says Prenner, who recently returned from Salone Internazionale del Mobile, the furniture show in Milan where he introduced the lathed containers and boxes he sells under the brand Like a Box. The response to the boxes made from Swiss pine, the turned salt and pepper mills, and the forged knifes was incredibly positive, he reports. Even Vitra showed interest. Traditional craftsmanship is back in demand, and Milan showed it.

The dream of paradise

In his own alpine domicile, Prenner takes his love for wood to the extreme. The large window reflecting the mountain peaks pops out against the buildings homogenous, light exterior. The words “Der Traum vom Paradies” (the dream of paradise) are stamped into the minimalist fine wood facade. In the back of the small house, the roof was cut open to add a floor for the new living room. The house’s exterior as well as the interior of the grand stube are almost entirely clad in wood. A total of 250 square meters (2692 square feet) of finest parquet were installed. The larch wood came from the valley here and was specially cut so the pattern of annual rings would run ever so calmly and evenly. The wood was processed by Prenner’s brother, who still owned a carpentry shop at the time and was capable of delivering on Prenner’s discerning specifications: “Many craftsmen merely do custom Ikea nowadays, craft and industry become more and more intermingled. Unfortunately, the sense of artisanship gets lost.”

Wood as the central element was an obvious choice for Prenner. Many other details developed over the course of the building process, he tells. “It’s like working on a sculpture. Many people want to plan everything in advance and then execute one to one. That’s why I don’t like collaborating on other architecture projects.” Prenner likes to be inspired as his work unfolds. The entryway, for example, was so dark you could hardly find the doorknob. So Prenner, without hesitation, tore open the ceiling to create light, which now floods the hallway from the stube and living room above. The white marble floor brightens up the foyer still more. The stone was quarried 30 kilometers (ca. 19 miles) from here, in Laas, and counts among the hardest and whitest marble stones. “It should be self-evident to use materials from the region, and not stone from India,” Prenner notes. “There’s a new aspiration. People want to know where things come from, where materials are sourced. Things of permanence provide comfort in uncertain times.”

“There’s a new aspiration. People want to know where things come from, where materials are sourced. Things of permanence provide comfort in uncertain times.”

The former stube, where the original, 200-year-old wood paneling has been completely preserved, was converted to the master bedroom. After all, the house’s central theme is the view to the outside—and the ground floor affords prime views. Thus, the classic arrangement of stube downstairs and bedroom upstairs was simply flipped on its head. The master bedroom’s ensuite bathroom marvelously harmonizes the white marble and the larch wood. The freestanding wooden bathtub is the focal point.

Prenner preserved the old stone staircase—or its remnants—as decorative element and a nod to the old structure of the farmhouse. The modern, floating wooden stairs and the bridge—or wooden walkway—to the living room on the second floor create the contrast. “During construction, a wood plank led across there, and I found the open crossing over the hallway interesting,” Prenner reveals.

The old roof joists were preserved and support the pitch of the roof, where the living room is. Five steps lead to a narrow loft Prenner installed along the gable wall with a long panorama window, again providing spectacular views to the outside. From his desk, the artist can see the cows grazing on the lush meadow.

And the light. Prenner often missed the light when he was in Munich, particularly during the long, gray winters, he remembers. Blue skies and the special light only snow can create—here, in his house in South Tyrol, he integrates it, plays with it, lives with it.

Work and art live together

Paintings and other art objects are piled up in the living room. “This is intentional,” Prenner says. “I wanted work and art to mix. I cannot separate them anyway.” Still, he is currently building an atelier on the premises. Before, when he lived in the city, he primarily created prototypes. But now, he likes to be more hands-on in the production, together with his partner, Ingrid Seebacher. The wood for each container, which is blackened in the fire, comes from a particular tree Prenner photographed beforehand and numbered the wood sections. The photo of the marked spot from where the wood was cut is sold together with the respective object—one of the artist’s many ingenious ideas. You can discover them all over the house. Art objects made from wood waste. Leftovers from a series of chairs you assemble yourself from four pieces of wood, and which Prenner became known for. These clever chairs don’t require glue or screws. In Prenner’s home, they are part of a group of miss-matched chairs around the large dining table and around the cozy stube. “In the old days, there was no ugly furniture because it was all made from solid wood,” Prenner contemplates. “But a lot is happening now. People are sick of cheap stuff made in China.” Prenner regards sustainable and organic as standard, which shouldn’t need to be pitched on a label. Sitting by the fire, he talk about the region here around Mals, soon to be the largest community in South Tyrol that is completely pesticide free. He tells about a baker who has re-sown old spelt ears from the eighteenth century and is now selling spelt bread. Stories like this are fitting for the stube and the beautiful, pristine landscape. Looking out the window and at the mountains, I can appreciate that one man's dream of paradise has come true here. △

“In the old days, there was no ugly furniture because it was all made from solid wood.”

Othmar Prenner was born in 1966 in Schlanders, South Tyrol, Italy. After an apprenticeship in carpentry, he studied sculpture at the HTL Innsbruck, Austria, and later at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany. The website Dinge und Ursachen lists Prenner’s many projects and exhibitions. You can purchase his Swiss pine boxes and containers from the online shop Like a Box.

Othmar Prenner was born in 1966 in Schlanders, South Tyrol, Italy. After an apprenticeship in carpentry, he studied sculpture at the HTL Innsbruck, Austria, and later at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany. The website Dinge und Ursachen lists Prenner’s many projects and exhibitions. You can purchase his Swiss pine boxes and containers from the online shop Like a Box.

The Tree-Hugging Woodworker

A portrait of California furniture-maker Sean Woolsey

Sean Woolsey loves trees. He celebrates the perfect imperfection of the trees' inner beauty by making wood furniture by hand in California.

Woolsey, now in his early thirties, has always made things. From sewing clothes to building skateboard ramps to baking bread. In 2010, he began making furniture, out of curiosity more than anything else. He deconstructed old furniture to learn how things are made. The first real piece of furniture he built himself was a writing desk for his then-girlfriend. She liked the gift, evidently. She married him.

Woolsey’s work and life is strongly influenced by the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which recognizes the beauty of imperfection as imprint of time. To the wood artist, wabi-sabi is embodied in the naturalness of the uneven, asymetrical touches to remind us of our own and the trees' perfect imperfections. In contrast to mass-producing furniture, which can take away these imperfections, Woolsey chooses to show the truth and rawness of wood, worked by hand.

The California native, who admits to obsessing over the quality of every piece that leaves his atelier, has always been captivated by the beauty of nature’s artistry and gains inspiration from the grandeur of a mature tree and the elegance contained in its wood. In his work, he has stayed true to the same simple ideal over the years: He designs and makes things he wants in his own home. And today, that's the place the entrepreneur shares with his wife, Sara, in Costa Mesa, California.

We caught up with the designer, furniture-maker, and fine artist only a short time after the birth of his daughter, Ondine, to talk about what home means to him, what traditions make his his modern products timeless, what inspires his designs, and more.

A conversation with Sean Woolsey

Who are you, in a nutshell?

A husband, father, artist, woodworker, tinkerer, artist, businessman, creative, friend, surfer, ping pong enthusiast, amateur knife-maker, bread-maker, pizza-creator, dreamer, risk-taker, traveler, tree-lover, ever curious human.

How did you grow curious about designing and making furniture?

It started very naturally and slowly. I was burnt out on making clothing and running my own clothing line. I was drawn to creating things with my own hands and to being more connected with what I was making, instead of just designing it and having someone else make it. I have a real obsession with creating, whether it be a pizza oven in my yard, furniture, a knife, or my own house.

"I have a real obsession with creating, whether it be a pizza oven in my yard, furniture, a knife, or my own house."

What inspires your designs?

So many things and people, but mostly the inspiration is rooted in making furniture that I would like in my own house and like to own for years, not just what is on trend. Much of the inspiration comes from the act of designing and tinkering around. Designs evolve, ideas feed other ideas, and things move with movement.

"Designs evolve, ideas feed other ideas, and things move with movement."

Your modern products appear rooted in tradition. What timeless merit drives your practice?

Functionality, with an utter respect and appreciation of materials and craft.

Is there a continuous theme to your designs?

I don't think so. I think, the only theme is making the best quality products that we can. The theme of materials and design is always changing and progressing.

How do you choose and source your materials?

The wood we use is predominantly American hardwood, such as walnut, white oak, or maple. We purchase most of it locally and occasionally purchase directly from mills, usually on the East Coast. We feel honored to work with wood, and we love trees. We plant a tree for every piece of wood furniture we sell, in honor of the customer, in partnership with the Arbor Day Foundation. It is our way of giving back to nature what it has loaned to us. We also work with steel, brass, glass, leather, et cetera. And we are always looking for new and fun ways to incorporate mixed materials and creating a story with the materials. We are fortunate to have many other talented crafts people locally, who help us with these other materials.

"We feel honored to work with wood, and we love trees."

What makes you a modernist?

The way of thinking about clean, good design that is functional, beautiful, and accessible — and designing to that.

What does quiet design mean to you?

Quiet design to me means designing slowly and enjoying the process. I often enjoy the process more than the end result, as many artists would.

"Quiet design to me means designing slowly and enjoying the process."

Talk about the immensely beautiful fine art pieces in your Copper Series and their synergy with your furniture-making.

The art is a release for me. It always has been. It is the complete opposite of furniture-making, which is very accurate, wrong or right, and precise. The artwork on copper is fluid, free-flowing, expressive, and experimental. Mistakes often make it better or more interesting. The Copper Series was inspired by the ocean, and its meaning to me. The series is ongoing and ever-evolving but always the same size and always inspired by the ocean, whether it be the color, movements, or captivating calm or power it holds.

Describe your dream home...

A home that is comfortable, in a beautiful location in the mountains or desert, with treasures that we have collected all over the world, and open to sharing meals with friends and family.

What does “home” mean to you?

A refuge where we can relax, recharge, make memories, share stories, laugh, cry, and feel good about it all.

What’s your favorite place in the world?

Oh, so many. I have been fortunate to travel a lot internationally. I am really drawn to Japan, and their culture and way of life. To me, Japan is simple, humble in its design yet meticulously thought out, timeless in its approach to craft. And the Japanese are the most focused people I have ever met. The mixture of it all is super intoxicating and inspiring.

What’s most important to you in life?

God. My family. Friends. Creative pursuits. Having fun.

Who is your design icon?

There are so many. The short list is Wharton Esherick, Dieter Rams, Robert Rauscheberg, Lloyd Kahn, Sunray Kelly, Jay Nelson, and Jean Prouve.

Who inspires you to be the person you are?

My wife and my friends largely inspire me to be who I am. As iron sharpens iron, they are constantly encouraging me, whether they know it or not.

What is your life philosophy?

This quote by Mark Twain sums up a lot of my life approach: "Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover."

What are you working on these days?

We are constantly working on new designs; right now, some chairs. I am also working on some copper art, as well as a new art series that is going to be really fun. Also, we just had a beautiful baby girl three weeks ago, so... working on that right now (laughs). △