Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Minimalist Pottery in the Kyoto Mountains

An intimate visit with husband-and-wife pottery artists Momoko and Tetsuya Otani at their home and studio in Japan

The Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto departs not one minute late, travels almost 200 miles an hour, passes Mount Fuji on the way, and pulls into Kyoto’s vaulting modern station not one minute early. From there it’s 40 kilometers by car to Shigaraki, an industrial mountain town, where I’ve come to visit a ceramic artist whose work has transfixed me on Instagram for the past ten months.

Shigaraki is home to one of Japan’s “six old kilns.” The most admired pottery here—tea bowls and sake cups made from local iron-rich clay—is often misshapen and haphazardly glazed. Much is left to the felicitous violence of earth and fire in wood-fueled kilns. These clay items, used in the exquisitely calibrated tea ceremony, are prized for their imperfections, reflecting the wabi-sabi philosophy in which earthiness, transience, roughness and decay reveal the essential nature of the world.

Such is Japan: hyper-curated, thrillingly modern, clockwork precise—then offering you a tea bowl that seems primeval.

The ceramic artist I’ve come to see, however, is Tetsuya Otani, whose work departs so thoroughly from the Shigaraki style as to seem from another world. Otani’s hand-thrown porcelain chases the precision of machine manufacture. Its skin is smooth and naked, like that of a baby. I wanted to know why he was making such beautiful but plain stuff.

Right now, though, I have a few hours to kill, so I drive into the mountains to find the I.M. Pei-designed Miho Museum. The Miho is a kind of Japanese Getty, opened in 1997. It’s perched on a thick-forested mountain top like something a hermit might build if the hermit had several hundred million dollars. To reach it you walk through a hill via a gleaming, curving science-fiction-y pedestrian tunnel and emerge on a bridge that’s supported by a harp-string array of steel cables. The Miho was commissioned by an industrial-fortune heiress who also made time to found a sect in the 1970s, variously described as an art-centric religion and a sinister cult.

As traveler’s luck would have it, the museum is showing an astounding collection of ceramics by the 18th-century artist Ogata Kenzan, whose name means “northwest mountains.” His painted cups, bowls, and trays leave the viewer giddy, so varied and playful are they in style and form.

At home with Momoko and Tetsuya Otani

Five or so kilometers from the Miho is the home that Tetsuya Otani shares with his wife Momoko—also a gifted ceramic artist—and their three girls and a dog. It’s beautiful, with farmhouse mud walls and high wood beams that employ traditional temple joinery. Everything on the main floor revolves around the kitchen, which is far larger than usual in a Japanese house, reflecting the Otanis’ passion for communal cooking and eating with friends, many of whom also make pottery. The shelves, in the dining area and kitchen, are filled with both Tetsuya’s and Momoko’s pieces.

The work of Tetsuya Otani

Lately attracting attention among collectors in Beijing, Shanghai, and Taiwan, Tetsuya shuns both wabi-sabi imperfection and Kenzan decorative exuberance. Everything he makes is to be used, mostly in the kitchen or at the table: tiny matcha urns with clinking lids, curved-belly flower vases, delicately spouted teapots, tiny soy dispensers, little round boxes. The pieces are finely lipped and polished to a supple smoothness; their creamy matte glaze begs to be caressed.

Tetsuya’s pottery has thrown off all temptation toward decoration. The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because “things that work give pleasure.”

"The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because 'things that work give pleasure.' ”

He studied in Kyoto, hoping to design cars, but when the economy skidded in the nineties, he shifted to graphics and ended up teaching product design (“how to make molds”) at the Ceramic Institute in Shigaraki, where he met Momoko and, on the side, learned throwing and glazing clay. By 2008, their house was built and he embarked on a ceramic career. He’s now in his late thirties.

I watch him work in the studio, which has wheels for him and Momoko, as he forms and pokes a bit of clay that will become a tiny strainer inside a teapot. A few feet away, a large machine mixes clay while sucking air from it, then extrudes large, irresistibly smooth noodles of the stuff. The machine is close to the same color as the clay. Tetsuya grins and admits he had it custom-painted to obliterate the standard industrial green. A clue to his fastidious brain.

The pure cup and the pure bowl

Later, we sit at the long kitchen table and look at bowls and cups and teapots and plates and discuss this idea of removing information from one’s work.

“The pure cup,” Tetsuya says, through Momoko’s translating, “and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

“The pure cup and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

One may begin with the form of a traditional Japanese offering bowl. Decorative motifs are removed until it approaches neutrality. Eventually you “come down to the point where we can use it on our table, not for the gods’ offerings.”

Momoko adds: “Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.” He produces smooth dinner plates as blank canvasses for food—altars, really. They’re used in fancy Osaka and Kyoto restaurants to showcase chef art. His works are unsigned, unmarked.

“Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.”

But cultural negation negates a specific culture, and Tetsuya says he has lately realized, when showing his works in China, that they are in some way indelibly, irreducibly Japanese. “I now feel that,” he says, “but I don’t have the answer yet about why I feel that way.”

The potter approaches, but never finds, ideal functionality. Tetsuya tweaks the ancient teacup form a wee bit from batch to batch, always seeking the right feel of cup in hand, the right curve of handle against thumb and finger. This lonely, incremental search for ideal form, endlessly repeated, is itself very Japanese.

The motivation is pleasure, however, not denial. Tetsuya and Momoko are exuberant foodies, and have found that their table-centric philosophy resonates globally through their gorgeous Instagram feeds, @otntty and @otnmmk, with more than 20,000 followers between the two for their pictures of utensils and food.

Tetsuya is also funny. He calls the clay mixing machine Mr. Hiroshira, “my only employee.” What about the beautiful industrial kiln in the next room, I ask? “No,” he says, “I work for it.”

Return to Kyoto

A few nights later, in Kyoto, my wife and I visit a little chocolatier and bakery called Assemblages Kakimoto, near the Imperial Palace. In the minimalist showroom up front I buy a box of orange biscuits enrobed in dark chocolate, each biscuit not much bigger than a postage stamp. Beyond the front space is a narrow, pretty room with a half-dozen seats or so against a counter, facing a tiny kitchen. We order chocolates and cakes and glasses of thirty-year-old palo cortado sherry. Two women to our right—the only other customers in the café—have come for the chef’s omakase dinner. With each course they look gobsmacked, enraptured by the treats placed in front of them. It’s beautiful food, for that is the Kyoto style. Each composition sits on the pale canvass of an Otani plate.

The entanglement of much fuss and no fuss that lies at the heart of many things Japanese is hard to describe, but when I palm one of the Otani pieces that we brought back from Japan, it seems to embody that contradiction. My favorite is a little round vase, the size of a tennis ball, whose satin smooth sides curve up to a sharp-lipped hole that’s big enough to accommodate the stem of a single bud. In weight and delicacy and touch and every other aspect the vase seems, to me, as close to perfect as it can get. It holds a lot of information about Japan. △

Solid Form

Shaping a clump of thought: A visual portrait of ceramicist Kelli Cain

We fell in love with Kelli Cain's pure and honest ceramics at first sight when writer Winifred Bird and photographer Torkil Stavdal visited the artist for us at her studio in the Catskill mountains. Revisit her through an artful video...

earth - air + water + force / rotation x fire = solid form

This is the formula of ceramics artist Kelli Cain's creative work. In "Breakable Minimalism," Alpine Modern discovered the many-talented maker and her earthy, minimalist tableware.

Now, filmmaker James Jenkins has created a visual portrait to showcase Kelli Cain's process through a meditative stream of consciousness. The process of thinking is taking a malleable substance—a clump of thought—and shaping it. It solidifies mid-process into a shape, perfect and imperfect, unique and personal. Cain's style is simple, beautiful, and speaks for itself.

(In)complete thoughts in response...

Solid Form - Kelli Cain from James Jenkins on Vimeo.

"The process of thinking is taking a malleable substance—a clump of thought—and shaping it."

Love and Loam

An Austrian artist family makes rammed-earth architecture, stoves and raku tiles

Earthen materials bond an Austrian family of artists: The applied-artist father builds with rammed earth and the ceramicist mother and graphic-designer son create tiles using an ancient Japanese pottery firing process. All their work is deeply rooted in ancient techniques, yet their designs are expressively modern.

“Never.”

Trotting behind his father around countless construction sites, a teenage Sebastian Rauch convinced himself he would never follow in his artist parents’ footsteps.

Born this way

Now thirty and his hormone levels long balanced, Sebastian has succumbed to the truth: The love for elemental design, form, and earthen materials is in his DNA. His parents are ceramic artist Marta Rauch-Debevec and artist-builder Martin Rauch. She runs the tile label Karak; he heads Lehm Ton Erde (Loam Clay Earth). Together, they share a studio space in Schlins in western Austria’s Vorarlberg region, tucked between the German and Swiss borders and known for supreme skiing.

“Both my parents have art degrees and chose art as their livelihood,” Sebastian tells. “Somehow, it rubbed off on the children.” Today, he works as a graphic designer in Vienna. His sister, Anna Pia, is currently taking a maternity break from earning her degree in art pedagogy.

The son of two artisans admits that neither the material loam nor his father’s building sites interested him as a child. “I was all thumbs in construction, which led to a lot of tension between my father and me during puberty.” To his parents’ chagrin, young Sebastian preferred to spend his days in front of the computer. “I was engrossed in anything to do with science fiction and Japan, whereas my parents are much more down to earth, literally.”

Rammed earth

Sharing a studio compels the elder Rauchs to amalgamate their crafts. “Marta and I have been working in the same space together for more than thirty years,” Martin says. “In terms of materials and processing techniques, there are many synergies between ceramics and building with loam, which help us both realize our work.”

To the family, loam, clay, and earth symbolize the holistic philosophy inherent in their art: Loam represents craftsmanship and technology, clay stands for art and design, and earth embodies the sustainability of building with loam.

Martin, who sees himself as an applied artist rather than an architect or designer, is known beyond the Vorarlberg region for practicing the ancient technique of compressing loam into a distinctive building material as sturdy as concrete. His desire to architecturally design with earth grew from his early work as a ceramicist, oven builder, and sculptor. Today, he focuses on the aboriginal rammed-earth technique, which he approaches with innovation. He builds entire buildings from loam as well as indoor components, such as wood-burning stoves, flooring, and interior walls.

The process of compressing soil is time tested. Parts of the Great Wall of China were constructed from rammed earth. “Being able to create solid, bearing walls from such elemental materials fascinates me,” Martin says. “It requires careful study of the material but also courage. For example, one has to be able to allow the erosion.” External rammed-earth walls facing the elements will lose some surface, exposing stones and leaving a pebbled pattern. “Once we can accept the erosion, we can recognize its many benefits,” Martin explains. “We must recognize that its water solubility is really the most valuable virtue of loam as a building material.” His structures are 100 percent recyclable, often using ground dug up during a building’s own construction phase.

“Being able to create solid, bearing walls from such elemental materials fascinates me.”

His building materials and techniques are deeply rooted in tradition, yet Martin’s designs are expressively modern. “This very juxtaposition inspires me,” he says. “With the emergence of modern building methods in the last two centuries, building with loam was rarely considered, downright superseded, and degraded to the poor man’s building material.”

The Austrian artisan, who is currently cladding Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in rammed loam, is confident that quality modern rammed-earth architecture with progressive, adapted techniques can once again valorize the image of building with loam.

Climate control

Breaking new ground in sustainable building spurs Martin’s creativity as artist and craftsman. “I love developing new ways of contributing to an anthroposphere that is more conscious of the environment and mankind,” he says. “Loam as building material is pure inspiration.”

Loam is available as local material almost anywhere in the world, meaning short, to no, hauling. “About 80 percent of our own home’s building material, for instance, came from its excavation pit,” Martin says. High efficiency and low primary energy are further benefits inherent in rammed-earth buildings. Locals identify with his work for these sensibilities. “It’s not unusual for our projects that the principal or the villagers join in building.”

Bringing the rammed-earth technique into the twenty-first century is a challenge the builder approaches from a business standpoint. “In Europe, it is important to react to the rationalized and industrialized building sector,” he explains. “For us, the prefabrication of rammed-earth components plays an integral role. It allows us to build much more efficiently and according to today’s construction timelines.”

Rammed-earth interior walls promote a well-tempered indoor climate. The enormous mass abates temperature extremes and superbly regulates humidity. If you have eaten a Ricola herbal cough drop, you have a connection to Martin’s work. He collaborated with Pritzker prizewinners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, founders of the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron Basel, on the Ricola Herb Center near Basel. Martin’s loam walls promote ideal humidity levels for storing and processing the herbs.

Haus Rauch

Though Martin has been working with rammed earth for more than three decades, the home he built for his own family was a test bed for further adapting and refining his technique.

The 200-square-meter (2,150-square-foot) home built into a steep southern hillside above Martin’s native town of Schlins was completed in 2008. The design was a collaboration with Zürich architect Roger Boltshauser.

In its orientation and form, the house directly speaks to the topographic flow of the site and the context of the landscape: A monolithic structure like a sculptural block is literally pushed out of the earth. The use of solid rammed-earth walls combines this architectural intention with the desire to construct an ecological building exclusively made of natural materials.

The mother of creativity

Marta, who was born in Ljubljana, Slovenien, and studied ceramics and product design at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, never urged her son or her daughter to work with her. “Simply following in your parents’ footsteps doesn’t bring you happiness. I wanted them to cultivate their own dreams and visions, so I never thought that one of my children would one day work with me.”

Having been an independent artist working on theme-based projects for exhibitions and sculptural ceramic objects, Marta herself hadn’t planned on specializing in tiles. But she knew she wanted to incorporate ceramic art in the new house.

After working with a low-fired technique known as raku, a traditional Japanese pottery process, for twenty years, Marta wanted to explore tiles as medium. “I was looking for a tile design for the house when I discovered the beautiful patterns Sebastian was creating on his computer,” she remembers. He says he created the designs “just for fun.” Marta wondered how she could transfer her son’s digital doodling to her tiles and began experimenting with screen printing. “When I created the first samples, we were all surprised how stunning the combination of the raku tiles and Sebastian’s patterns truly was.”

“I was looking for a tile design for the house when I discovered the beautiful patterns Sebastian was creating on his computer.”

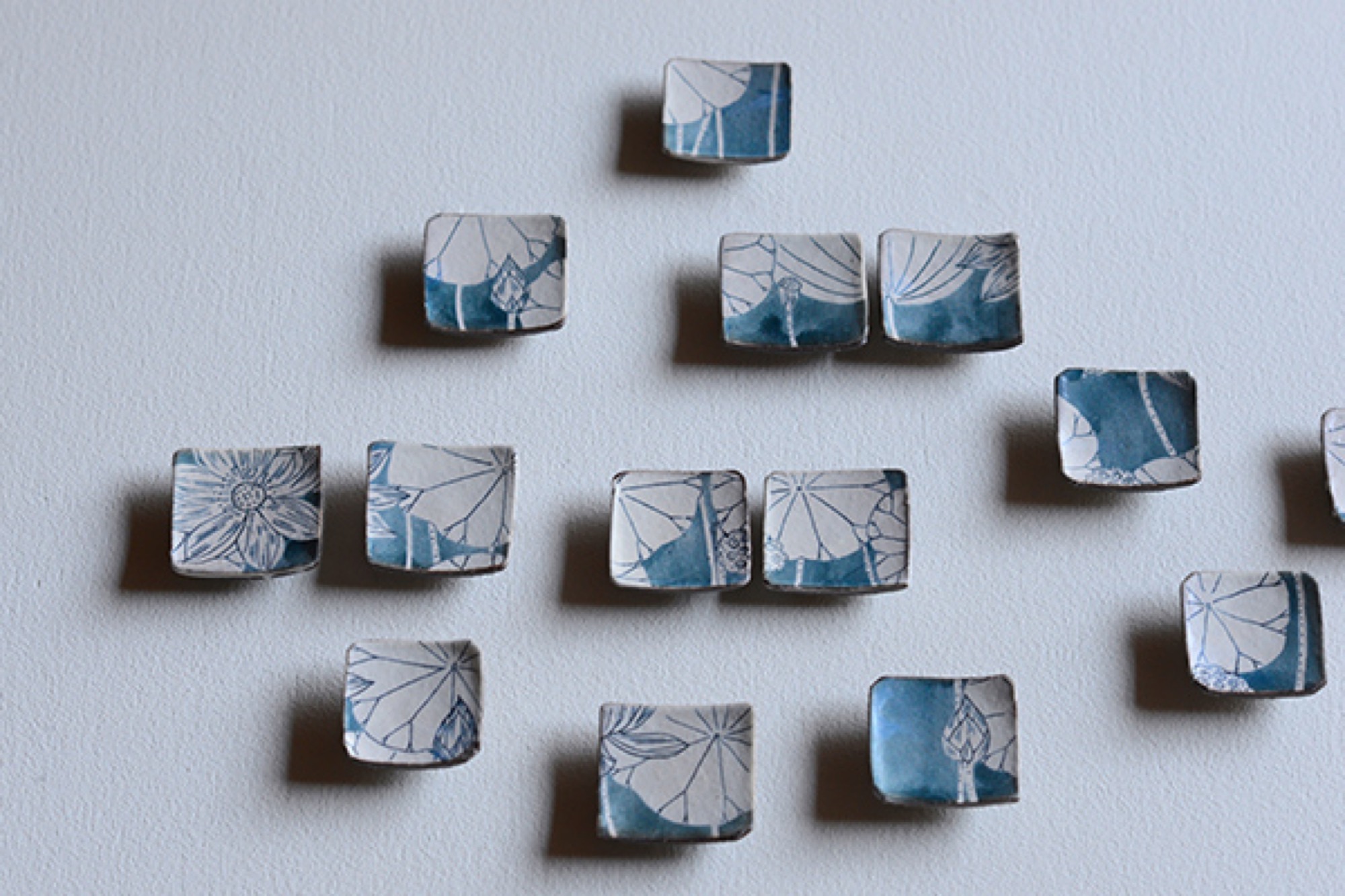

Karak tiles

The Karak brand was born. Marta and Sebastian’s Karak tiles—each a unicum—embody the elementary relationship between the Eastern and the Western world. Captivating geometric ornaments, the result of repeating, digitally created design patterns, are married with the century-old Japanese raku technique that gives the tiles an inimitable air of chance.

The tile material is a combination of different kinds of clay and loam mixed with quartz sand and fireclay. Pressed into shape, each tile is retouched by hand, the designs applied by silk-screening.

As the tile is red at about 1,000 degrees Celsius (ca. 1,830 degrees Fahrenheit), the material’s transforma- tion becomes palpable—the low-fired technique makes it porous and gives the final product a deep, organic sound at the touch and a warm haptic.

Still glowing, the tiles are removed from the kiln one at a time and immediately hermetically buried in sawdust. The void of oxygen and the smoke have an intense effect on the surface that varies for every piece. The color changes with the glaze; hair-thin cracks are blackened.

Finally, dunking each tile in water reveals its finished character. Transformed by the temperature shock, the glazed surface is brushed off, evincing a craquelure—like a fine net tying everything together.

Starting Karak wasn’t a conscious decision but rather a mother-son collaboration that grew organically. At first, the two intended to create the tiles only for the family’s villa. Then a book was published about the unique house. “On occasion, people began talking not about the Rauch house but about that house with the beautiful tiles,” Sebastian remembers. “People were asking us where we got those tiles...that’s when orders began coming in.”

“When we created the tiles for the house, I suddenly knew the charm of these tiles,” Marta says. “After all these years, I am still excited every time I walk in the door.”

Futuristic fantasy meets ancient technique

Sebastian’s passion for science fiction inspires the patterns he designs for the tiles. “I love to connect antipodes, things that seemingly don’t go together, the interplay between contrasts...that tipping effect.” His KuQua design, for instance, combines spheres (Kugeln in German) and squares (Quadrate). “When you deconstruct these two shapes and recombine them, they become almost unrecognizable in an entirely new shape. However, there is an underlying geometrical clarity and calmness that makes me feel like I didn’t design this shape; rather, I found it. At the same time, there is constant movement as the eye meets the pattern, like a deep mantra lancing the universe, like yin and yang.”

His mother is no less fascinated by the repetitive geometric patterns’ tipping effect. “Depending on how the eye focuses in, the design can suddenly appear three-dimensional,” she says. “In fact, we created a three-dimensional tile, the TaOk tile, a tantalizing combination of modern geometrical design and something Oriental. Then, the ancient technique adds something very primordial...a beautiful enrichment.”

The raku process gives a brand-new tile the patina of a long life. “I am intrigued by something that looks so archaic, yet you can’t really assign the object to an epoch,” Sebastian says. “I like to envision an archeological excavation site where they dig out a temple and find patterns and artifacts that don’t have a place in our past, in the human past...so you may have discovered an alien temple.” The precise patterns, the exact geometry combined with the serendipitous process make Sebastian optimistic for the future. “In science fiction the future is often depicted as extremely slick and clinical, as measured and constructed. I rather like the thought of a future that is still sensual and vivid.”

The geometric patterns are calculated and carefully designed, with precise lines. But the firing process, the smoke passing through the tile, and finally the quenching in water is so incalculable that what was once smooth becomes structured, what was once superficial gains depths. “It is a movement between order and happenstance, between repetition and uniqueness,” Marta adds.

“It is a movement between order and happenstance, between repetition and uniqueness.”

Both Marta and Sebastian appreciate the synergies and new opportunities that come with sharing the workshop and resources with Lehm Ton Erde, particularly Martin’s tinkerer skills and powerful imagination.

“Growing up, I was pretty sure I wanted nothing to do with loam,” Sebastian admits. “Funny how I found my way back to the material.” In the end, he’s grateful his parents laid the groundwork. “I couldn’t imagine working like this if it weren’t for being a family.” △

“I couldn't imagine working like this if it weren't for being a family.”

Beauty from the Lab

Minimalistic ceramic labware matches the simple beauty of designer pottery

Minimalistic in form and manufactured with exquisite precision, classic laboratory ceramics, such as the tactual porcelain crucibles and skinny alumina trays by CoorsTek in Colorado, can be as strikingly decorative in a modern home as designer potteryware.

The area around the town of Golden, Colorado, feels ancient, with flat-topped mesas crowning tumble-down hills at the foot of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. Ridges heave up from the tilting plain like the backs of dinosaurs. Prospectors and scientists have uncovered Triceratops tracks hereabouts, petrified wood, and the fossilized bits of more than 200 plant species. The place is a beautiful old mess, its geology famous for minerals but also for clay, which is particularly fine and well suited to the making of ceramics.

Human-made

As reality is transmuted more and more into the virtual, I like to remember that everything made by humans is made from stuff pulled from earth or air. Silicon has a valley named after it, after all. Less well known is ceramic, deployed all over the high-tech landscape for its ability to insulate, resist, conduct, shield, and do other yeoman work. Ceramic traces a direct path between the most ancient manufacturing—humans were firing clay figures 24,000 years ago—and the Great iPhone Era.

I’ve loved ceramic ever since the time my mother was given a small collection of chipped and crazed Ming Dynasty bowls that had been dug up in Indonesia by Jesuit priests—friends of hers. I was ten. By their delicate feel and obvious durability, it was apparent that they were made of the same stuff—porcelain—as my mother’s English Spode china.

Ideal design from the cusp of modern

Decades later, while editing a science magazine, I started to collect laboratory ceramics. Vintage labware had begun to turn up on eBay: crucibles, funnels, casseroles, spoons, spatulas, and combustion boats. Basically: cookware for chemists. There were tiny dollhouse-scale crucibles as well as huge mortars that could hold 272 dry ounces of material. These pieces were utterly functional in shape, creamy gray or ivory in color, modern. But their modernity had a retro feel, echoing the apothecary. They had reached their ideal form and then ceased evolving: It was hard to tell a brand-new piece from one produced almost eighty years before. Modern, then, but from the cusp of modern.

“These pieces were utterly functional in shape, creamy gray or ivory in color, modern.”

My lab ceramic pieces usually sported a simple mark, “Coors U.S.A.” I didn’t think much about that until I moved to Colorado, drove through downtown Golden on the way to Vail, and passed an old brick building attached to a much newer one. A sign announced the CoorsTek advanced ceramics company, and I finally put two and two together.

Coors—a Colorado family company

Early this year, after signing documents affirming that I was not a spy and understood I was entering a facility governed by federal security laws, I got a look inside the CoorsTek plant where the labware is now made. It’s one of several CoorsTek factories in Golden, and the only one to which I was likely to gain entry: The rest of the operations, here and in Europe and Japan, are devoted to a myriad of high-tech products such as body-contouring ceramic armor plates for soldiers (also beautiful objects, by the way). It’s a billion-dollar private company, owned by the Coors family, that long ago leveraged its labware skills to make ceramic parts of exquisite precision, used in rocket nose cones and hip-replacement devices and highly specialized one-off bespoke projects like the high-intensity lights that memorialized the Twin Towers after 9/11. But it’s the labware that I was interested in anyway, the seed of the whole ceramic enterprise.

My guide around the factory was Rob Spurrier, who has been at the company for thirty-six years and is now plant operations manager. A formidable, matter-of-fact journeyman tool-and-die man, Spurrier seems to like that he works for a bleeding-edge technology company whose roots lie in methods you could learn at the community center.

“Making this product follows your fifth-grade pottery class that you might have taken at school.”

It’s true that despite the oversize scale of the kilns, casts, racks, and presses in the huge plant, there’s a handmade vibe. Pieces are generally pressed by machine, not thrown, but if two parts have to be joined together, the slip technique would be familiar to any potter. I spotted one fellow working on ceramic “furniture” (which is the name for pieces that other ceramics rest on during manufacture). A piece cracked apart in his hands; he chucked the shards into a bin and started on another. Everywhere were racks of unfired “green” labware, looking as fragile as any raw clay things, awaiting the kiln. “Pugs” of refined clay, known as body, made in a nearby Coors plant and shipped here in metal tubes, looked like enormous strands of Plasticine.

Porcelain from ancient China to 1940s America

Classic labware is made of porcelain, invented by the Chinese more than two thousand years ago and improved in the thirteenth century. It is made by pulverizing and mixing a white clay called kaolin with other materials into a paste, forming the paste into shapes, then firing it at very high temperatures until the minerals liquefy in a glasslike way and bond with the rest of the material. Not until the 1700s did the Europeans crack the formula and technique. One who succeeded was Johann Böttger, a German pharmacist-turned-alchemist. Soon, there were porcelain factories all over Europe producing housewares and decorative goods. Porcelain, improved again, proved ideal for chemistry. It resisted chemical attack. It was minimally porous. It retained its mass. It could be subjected to thermal shock. The Germans dominated its manufacture.

That last fact meant trouble for American labs when the blockade of World War I ended the importation of German goods. The US government asked local industry to fill the labware gap. One firm that responded was Herold China and Pottery, in Golden. It had been installed in a defunct bottling plant owned by Adolph Coors, founder of Coors beer, by a clay expert named John Herold. Its purpose was to make ovenproof kitchenware. The pottery did not prosper, though it had early success producing crucibles for lab use at the Colorado School of Mines, also located in Golden. Herold left, then returned in 1915 to tackle the problem of producing labware for the national market. Coors soon bought the company outright and installed his son, Adolph Jr., to run it.

Alumina brings advanced ceramics

The Coors company went on to produce much of the country’s lab ceramics. Not much changed until the 1940s, when Coors acquired technology for forming clay into shapes that were far more complex and precise than conventional porcelain techniques could achieve. Then alumina launched the era of advanced ceramics. With alumina, purified aluminum oxide powder is swapped for clay. The powder turns into a ceramic under tremendous pressure. Over the decades, the process was advanced to make ceramics from boron, silicon, tungsten, and more. The range of modern ceramics is now fantastic. They can be hard as metal yet melt at much higher temperatures than metal. They can conduct electricity, or not. They can transfer heat easily, or resist it. They have names like Y2 O3, yttria-stabilized zirconia. But one property they share is beauty. Ceramics beg to be touched.

“The range of modern ceramics is now fantastic…. But one property they share is beauty. Ceramics beg to be touched.”

“I love the surface finishes we can achieve, and the feel of ceramic,” says Harrison Hartman, who runs marketing at CoorTek headquarters and keeps a foot-long, wood-handled CoorsTek pestle in his office. “Ceramics can be heavier than metal, and more dense.”

Jessica Nall, one of the company’s de facto historians, has an IT background but after joining CoorsTek became obsessed with clay and took a pottery class to learn to throw it. She got permission to hand-throw some scrap CoorsTek lab clay outside the factory. “You can throw it,” she found, “but it’s really difficult. I had to bring it back here to get fired and glazed because a traditional hobby kiln is much lower temperature.”

As the factory tour came to a close, I found myself wanting to cut a slice of clay and take it home as a piece of advanced Play-Doh. I sensed that Rob Spurrier would rule this not only verboten—the formula is proprietary—but silly. As a man who had overseen the production of millions of pieces of labware for scientists, he seemed to find my interest in crucibles and combustion boats as objects of beauty somewhat odd.

In 2011, Darrin Alfred, Curator of architecture, design, and graphics at The Denver Art Museum, gathered sixty-four pieces of CoorsTek for a small show called Potters of Precision. Alfred was attracted to the “simple, clean, straightforward, unadorned quality of the product,” and told me that Edgar Kauffman Junior, famous director of the Industrial Design Department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, had connected the dots between labware and the aesthetic of modern home ceramics almost seventy years ago. On page twenty of Kauffman’s small 1950 book, What is Modern Design?, there’s a photo of porcelain dinnerware by the great Eva Zeisel, next to several pieces of CoorsTek ware. The latter, Kauffman wrote, was “used widely in modern homes because of elegance, usefulness, durability and low cost. In a laboratory, beauty is not required, but [it] appeared spontaneously in vessels that serve the scientists’ precisely stated needs.” I own vintage Zeisel dinnerware, swoopy, thin and minimalist, which I keep in my kitchen. I also have a stack of sixteen little CoorsTek alumina lab trays, each about the length and width of an old matchbox, on my desk. Unglazed, with a lovely matte finish, they have a pale ivory color that indicates 99.5 percent pure alumina. I pick them up, rub them, clank them together; they give off a modern sound, somewhere between that of metal and glass. They’re not something Ming Dynasty porcelain potters could make, or Johann Friedrich Böttger, or for that matter Adolph Coors, but they are something they would all recognize and admire. Something real, and of this earth, ancient and new at once. △

Breakable Minimalism

Maker in the Catskill Mountains: Ceramics artist Kelli Cain creates earthy, minimalist tableware

As she creates earthy, minimalist tableware, Kelli Cain often muses on the people who will sip from her cups and slurp from her bowls. A visit with the many-talented maker in the Catskill Mountains, New York. What is a cup? Is it simply a container for our morning coffee or afternoon tea? Or is it a vessel for more ethereal brews as well—memories of hot chocolates past, aesthetic preferences, even our imagined ties to the person who shaped the cup and the patch of ground where its clay was dug?

These are questions that potter Kelli Cain ponders often as she sits in a sun-filled corner of her farmhouse in the Catskills, throwing cups and plates, coffee pour-overs, and lemon juicers. Cain is thirty-six and—though her earthy, comfortingly simple tableware belies it—just two-and-a-half years into a career as a commercial potter. Before that, she was (and still is) a video artist, composer, and industrial designer. With her husband, Brian Crabtree, she developed a highly successful line of electronic instruments, which the two manufacture under the name Monome from their eighty-year-old refurbished dairy barn. Pottery is one form of creation among many for Cain, and she probes it with the same intense inquiry she applies to them all.

Utilitarian beauty

“I do believe in utilitarian beauty,” she said on a recent afternoon, leaning her red-brown curls against the bank of windows behind her dining table and fixing her clear gray eyes on me. Beyond her, willows, apple trees, and meadow grass formed layer upon layer of green, ensconcing us in a private, summery world that felt much more than its three hours from New York City. “I think it’s really important that we have a respect for everyday objects, and I think the more energy put into a thing, generally the more we have respect for it.”

“I think it’s really important that we have a respect for everyday objects, and I think the more energy put into a thing, generally the more we have respect for it.”

I had driven up to the farm earlier that day, winding into the mountains on Highway 10 past the little town of Delhi with its peeling Victorians and weekend vacationers, and finally down a gravel drive into a valley where a man with buzzed hair and a long red beard stood knee-deep in garlic stalks, clipping off their spiraled tops (this turned out to be Crabtree). Cain was inside, boiling udon noodles and ladling broth into handmade bowls for our lunch.

“These are such magical little nuggets of flavor,” she announced, spooning a sweet-and-sour pickled shiitake from a Ball jar and slicing it into one of the bowls. She and Crabtree grew the mushrooms themselves in a stack of sugar-maple logs below the house. They also cultivate an apple and pear orchard for cider, grow vegetables, raise chickens, hold concerts, make music and art, and run their ceramics and electronic instrument businesses. On the wall of Crabtree’s workshop hangs a beach-towel-sized print by the Minneapolis-based artist Piotr Szyhalski that exclaims, “We are working all the time!” When I asked Cain if the slogan reflected her life with Crabtree, she replied, “If by work you mean doing things we enjoy, then yes.”

That life of shared creation stretches back almost to the day they met, in their first week of graduate school at the California Institute of the Arts. Cain was studying film and experimental animation, Crabtree, musical composition; they met at the library, where Cain was checking out a book on papier-mâché puppets. Very soon, she said, they became “everything”— friends, co-creators, romantic partners. Their first project together was a mechanical installation involving microsculptures and videos. Years later, a similar joint project led Cain to ceramics.

Finding ceramics

For that project, she and Crabtree wanted to make a group of tiny robots tap on clay sculptures inspired by bee and wasp architecture. Despite Cain’s complete lack of ceramic experience, she decided to make the sculptures herself—which, she noted as we slurped our noodles, “was a hilariously naïve thing to do.” Her three-month crash course in ceramics went forward, however, and it turned out Cain was a natural. An elderly classmate even commented that she should do it for a living. Cain brushed the comment off: She was just starting to build up Monome with Crabtree, and couldn’t imagine a life making cups.

Six years later, she reconsidered. By then she and Crabtree had fallen in love with the Catskills, bought their farm, and started to renovate its dilapidated buildings and plant its fallow fields. Around that time Cain fell seriously ill and was forced to spend an extended period in the hospital.

“When I came out,” she recalled, “I had a little bit of an epiphany that I needed to do something physical, to make things out of physical materials.” Encouraged by the comment from her former classmate, she decided to buy a wheel, kiln, and other equipment to set up a pottery studio.

“I had a little bit of an epiphany that I needed to do something physical, to make things out of physical materials.”

The first project she set for herself was throwing a series of bells. To get the tone right, she had to learn how to create continuous shapes with handles and walls of even thickness. From those she progressed to objects she wanted to use herself: deep, cone-shaped bowls to ladle her beloved udon noodles into, squat coffee pour-overs for her morning brew, glossy bottles to hold the milk from the goats she and Crabtree raised for several years.

The day I visited, her orderly studio was filled with projects at various stages of completion. On a large worktable sat two custom-order bowls (commissions from studio visitors account for the bulk of sales, she said), an assortment of juicers, cups, and bowls to restock inventory, and several prototypes for a line of candleholders. Finished tableware glazed mostly in whites and earth tones lined two large shelves.

Cain mixes her own glazes and combines them in her work with raw surfaces that rub pleasantly against the hand. Often, the farm’s landscape inspires her palettes. Cool whites evoke sky reflected off snow, and browns recall patches of bare earth (snow covers the farm for five months of the year). She told me she had recently tested sixty different shades of white, and had plans to try out more.

“I’m going back to white,” Cain said, taking a small corked vessel into her hands and rotating it to show me the gentle play of textures and tints. “I like minimalism. The variation of one color is such a beautiful thing.”

“I like minimalism. The variation of one color is such a beautiful thing.”

The ghost

Despite her current absorption in utilitarian beauty, Cain sees tableware production primarily as a way to acquire the skills she needs in order to incorporate ceramics more fully into her art. She has already begun to do so. Over the past two years she has created a series of ceramic spheres for use by the Stockholm-based master juggler Jay Gilligan. In performances filmed against the gorgeous frozen landscapes of Iceland and set to music by Cain, Gilligan lets the spheres drop and shatter, toying with the audience’s nervous hope that he will preserve the fragile objects. “My whole point was to inadvertently be in the room with him and almost choreograph his movement, because fear is now an element,” Cain said.

In a way, the concept echoes her fascination with ceramics as a secret bridge between herself and the people who use her cups and bowls in their daily lives. When I mentioned the parallel, she laughed. “Maybe it’s my obsession with being the invisible force in the room. I really think I might have a problem with needing to be the ghost,” she said. She was half joking, but as I said goodbye and drove away into the hills, I wondered: Perhaps the ghost was precisely what gave her objects their quiet, distinct beauty. △