Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

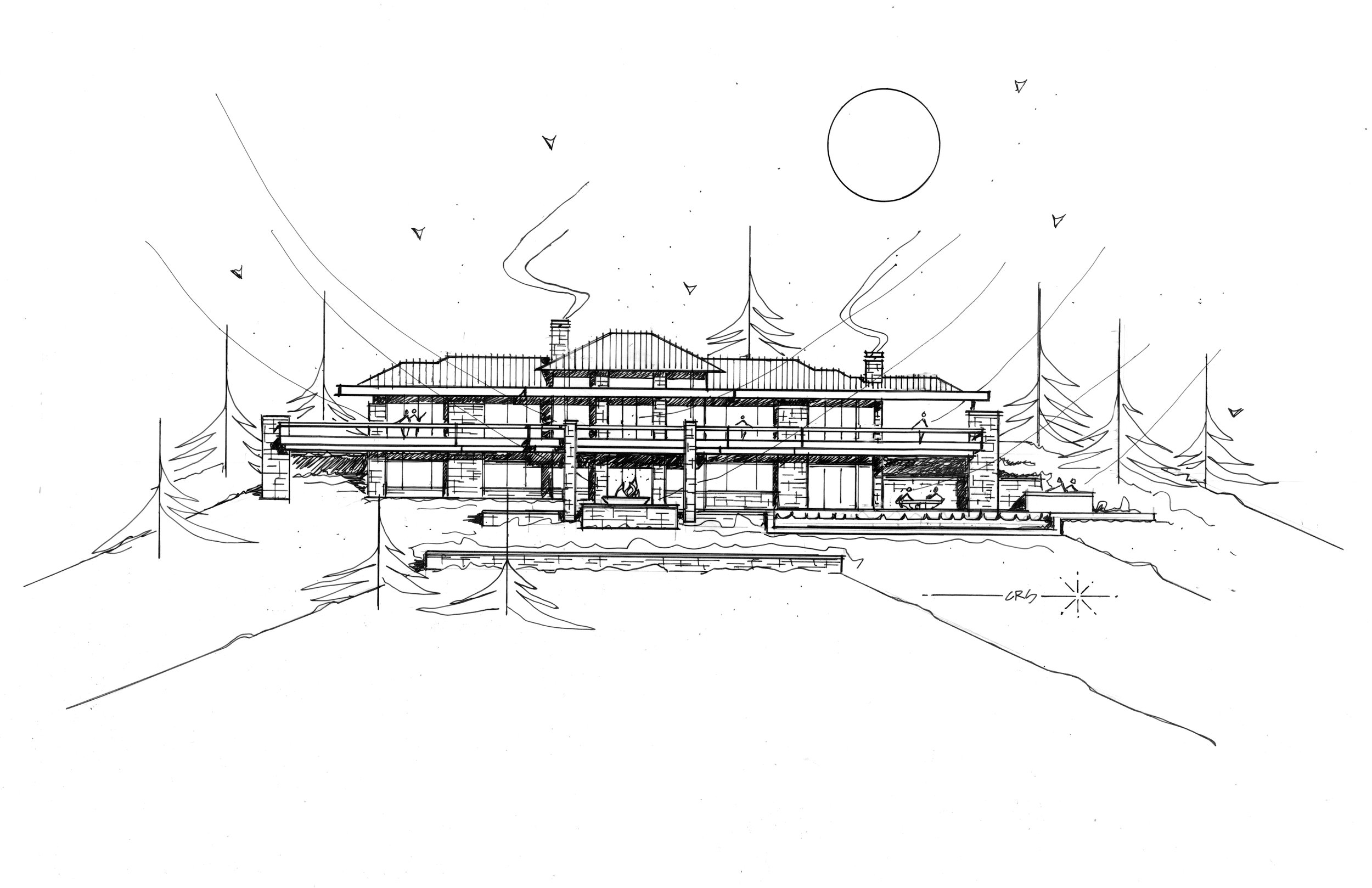

A Dream in Detail

Sharing a deep admiration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work and a devotion to detail, a retired couple builds the mountain home each envisioned before they even married. An intimate look at a dream come true.

Bob and Judy met on a blind date . . . What sounds like the beginning of a romantic love story—which it is—also leads into the inspiring story of two people who, on that first night discovered they shared a passion for architecture, the work of Frank Lloyd Wright in particular, and a lifelong dream of someday living in the Vail Valley, in a warm, modern house overlooking the ski runs of Colorado’s famous winter resorts.

“We wake up every morning and can’t believe we get to live up here,” Bob says today. The Michigan native visited Colorado for the first time when he was seventeen, on a ski trip with his buddies. “I remember thinking, ‘Someday, I want to live out here. Not in a ski-in/ski-out place, where you are up close to the mountain, but in a house with great vistas of snowcapped mountains.”

Forty years later, the man, who spent a career traveling the world as an executive for global brands, stands behind his marble kitchen counter, looking out over Beaver Creek and some of the country’s highest peaks soaring more than 14,000 feet (4,267 meters) above sea level. The dream house he built with his wife of eleven years was carefully sited so the windows of the great room frame the ski runs across the valley perfectly. “We wanted this feeling of a life-size trail map.”

“We wanted this feeling of a life-size trail map.”

Judy, for her part, grew up in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Her mother and father, too, shared a love of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture. “Every month, my father took my brother, my sister, and me to see a different Frank Lloyd Wright house. That had a profound effect on me, and is something we continue to like to do,” she says. “It’s also one of the strong bonds that Bob and I have, because he used to ride around Michigan and go to Frank Lloyd Wright houses, knocking at the doors and asking if he could meet the people.”

“Every month, my father took my brother, my sister, and me to see a different Frank Lloyd Wright house. That had a profound effect on me.”

The perfect plot and a modern master

It took one year to find the perfect lot, 9,125 feet (2781 meters) above sea level, at the end of a winding, aspen-lined road above Avon, Colorado. For an entire ski season after they bought the lot, the two came up from Denver on weekends. “Instead of skiing, we’d sit on the site and envision what our life would be like up here, and how we wanted to live in the house,” Judy thinks back.

“Instead of skiing, we’d sit on the site and envision what our life would be like up here, and how we wanted to live in the house.”

Then the new landowners needed to find an architect who could put their dream on paper. They hit the bookstores. “We were going through architecture magazines, pulling out pictures of homes that looked interesting to us,” says Judy. “And then we realized, it’s all the same architect.” The modern master whose work jumped out at them time again was Charles Stinson of Charles R. Stinson Archi-tecture + Design in Minnesota.

The internationally acclaimed architect had never designed a mountain home before; but having seen his previous work, Bob and Judy were confident he was capable of helping them achieve their dream. “Rare clients I know of who are such students of architecture,” Stinson says about the pair. “We hiked their site together, and we all had a harmony in the way we saw the world and the potentiality of architecture.”

Good design takes time

The couple as well as their architect appreciate Wright’s clean, horizontal lines, his strong sense of flow between indoors and outdoors, and the use of warm materials. Nonetheless, the design was not to be an imitation of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. “Bob and Judy’s house both integrates the materials and the geometry of Wright, but it also brings in a more modern aesthetic and materials and technology,” Stinson says. “We integrated the history of Wright’s contribution with a current, modern architecture.”

The two key design objectives were to maximize the views, and for the house not to pretend to be something it was not. The creative collaboration with Stinson took another four years before the clients felt the design was right. “Good design really does take time,” says Bob. “You get something laid out, and then it takes time to react to it.”

"Good design really does take time. You get something laid out, and then it takes time to react to it."

“I try not to think of it as obsessive compulsive,” says Bob, “but everything makes a difference in architecture.” He believes that paying attention to detail creates warmth and “zen-ness.” Good design is not for everyone to notice, but to recede behind form and function. Yet, a space that feels good and evokes an emotional reaction isn’t happenstance. “Attention to detail makes those details go away, and there is a calming feeling in that space,” says Bob.

Stone on stone

Stone is the protagonist among the house’s natural materials, both on the interior and the exterior. Devoted to detail, Bob and Judy wanted every stone on the interior to match the color and lines of its counterpart outside the glass panel to create unity between the outdoors and the indoors.

Every day for two years, up to ten stone masons worked onsite, hand-cutting and fitting hundreds of tons of stone brought in from Arkansas. “It really was a labor of love,” says Judy. “Three or four of them had been here the whole time, and they ended up being like family members.”

Adds Stinson: “All of us had such respect for each other, and for the site and materials, and a gratitude for the builders and artisans and their great workmanship.”

Of the hill

Constructed by Mark Fox of Fox Hunt & Partners, the 7,200 square-foot (669 square-meter) home sits on seven acres adjacent to thirty acres of open space to the south and east and borders the White River National Forest. Frank Lloyd Wright often spoke about building on the edge of the forest to achieve a sense of shelter.

The house is tucked into the steep mountainside to block the cold winds from the north. The south-facing indoor and outdoor living spaces reap warmth from the sun year round. Wrapping around the back of the house, the 125-foot upper deck over- looks the pool patio down below, providing covered and uncovered gathering spots. The resulting microclimates provide a comfortable place to sit outside, here or there, upstairs or downstairs, snow or shine.

Following Frank Lloyd Wright’s credo of not building on the hill but of the hill, the house is sited to descend down from an expansive flagstone auto court. “You literally feel more grounded with your environment,” Bob says. “The house would have felt completely different sitting up there.” Now, the home’s horizontal lines follow the horizontal ridge above.

“No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together, each happier for the other.” — Frank Lloyd Wright

Mature aspen trees surrounding the house provide the Wrightian sense of protection and privacy at the forest’s edge.

The welcoming native Midwesterners share their land with Colorado wildlife. Mornings and evenings, deer trot along their natural path, which traverses the property. A pair of foxes likes to hang out by the pool. Because of the down-sloping landscape, birds of prey hover at eye level. “We look out and there will be this huge red-tailed hawk, just stationary, with his landing gear out,” Bob describes. “It’s amazing to watch them at eye level. Usually you only get to see these birds high up in the sky.”

Building into the side of the mountain made figuring out the approach to the house “very challenging,” according to Stinson. “We studied the grades from both directions, and Bob said, ‘Let’s flip the house around.’ It actually worked out better.” The transition from the driveway to the house, which descends down the mountain, now provides an intentional experience. The architect and his clients even climbed on a ladder before siting the house to see the views from where the main level would be. “We wanted to take advantage of a sequence of experiences, so when you are coming into the site up above, you have a glimpse of what the view is going to be,” Stinson says. “The view disappears when you are in the auto court, which is surrounded with nature—so the uphill side is a grounding experience. Then you walk into the house, and boom, the big views let the spirit soar. You see so far and down the valley that you needed that balance of shelter and release.”

Elevated living from the inside to the outside

Inside, the house offers a different experience and view corridor from nearly every room and angle. The elevated interior design reflects the warm colors and materials of the Rocky Mountains throughout.

The main level’s great room and hearth room truly maximize the expansive ski-slope views the owners hoped for. “I can’t tell you how much time we spent with the surveyor on the siting,” Bob says. “He had mapped out all the peaks and we’d literally stand with the footprint of the house, and we moved it three times before they dug the foundation.” The luxury of time and attention to detail once again paid off. “We’ll get ready to go skiing and put the local news on to see about the conditions, and I sit here and have my coffee and say, ‘Well, I can just look at the actual slopes.”

The overhangs of the roof above the main level’s south-facing windows provide architectural drama but are also part of the house’s passive solar design. “In winter, when the sun is low in the sky, the warming sunlight goes all the way to the back wall, whereas in the summer, when the sun is higher, you get a little bit of morning sun, but then it’s blocked,” Bob says. “We didn’t turn on the air conditioning at all last summer.” Roof solar panels already provided one-third of the electricity, and with the recent purchase of 100 more panels on a solar farm sixty-five miles away in Carbondale, Colorado, all the house’s electricity now comes from solar power.

Entertaining dinner guests and hosting out-of-town friends and family are an essential part of Bob and Judy’s new mountain lifestyle, now that they no longer work “crazy hours” in the city. Thus, Stinson designed the main level for the couple to live and entertain dinner guests. A floating buffet visually separates the dining room and breakfast room while maintaining an open flow so guests at both tables feel connected.

Overnight visitors are known to call the lower level “Bob and Judy’s retreat and spa.” Indeed, guests have their private quarters downstairs, with intimate suites named after the respective resort in view and decorated with vintage ski posters mirroring the very scenery outside the window.

The window seats in the downstairs living room, in fact, are Judy’s favorite spot in the house, as she says the ski slopes look even closer from down here. The communal space with an open kitchen opens up to the sweeping pool patio with an outdoor dining area in the center, a hot tub on one side, and another outdoor fire pit off to the other side, where the family loves to roast s’mores at night.

Integrated into the guest wing are also a massage room, an exercise room, and an exquisitely curated wine cellar. The opposite side of the lower level has a bunk room, where Bob and Judy’s nieces and nephews like to hang out when they come on vacation and occasionally bring along friends.

Beneath the garage and a concrete ceiling are Bob’s pride and joy: a movie theater with Whisper Walls and a high-end listening room that boasts a pair of enormous Genesis 1 speakers. Still, the window-less über-impressive “cool area for the loud things” (as Stinson calls the two rooms) are not where Bob spends most of his time. He likes to sit on the lower deck, looking out over the large saline pool and the ski slopes just beyond. This is, after all, his dream come true. △

At the request of Bob and Judy, we are not publishing their last name or identifiable details about their mountain home's location.

Narrow Escape

Falling in love with an impossibly narrow lot on a mountain village's main street, A Denver architects builds a 15-foot-wide weekend home for his adventurous family

Incited by a seemingly impossible building site in an old railroad town above Vail Valley, Colorado, a Denver architect designs a 15-foot-wide sustainable mountain getaway as a speculative investment for sale. Then his adventurous family falls in love with the home. It was an eyesore. Passersby merely saw a ramshackle trailer overstuffing the 25-by-100-foot (7.5-by-30-m) lot on Main Street in Minturn, Colorado. Yet, André Vite spotted an opportunity.

The campus architect at the University of Colorado Denver and his wife, Ginger Borges, an oncologist at the University’s medical school, have a weakness for obscure properties. That evening three winters ago, however, they maintain they were not scoping out a new venture at all. The couple and their preteen sons, René and Niko, were headed to the old railroad town up Eagle River for dinner after a day of skiing in Vail. “We drove through Main Street Minturn, which is a town we go to all the time, and there was a mobile home for sale that was just totally wedged in and awkward looking,” Vite remembers.

Even though he didn’t know what to do with it at the time, the architect wanted that piece of land. And he got it without difficulty because the city planners had been eager to get that blot off Main Street.

The draftsman went home and started sketching.

S(e)izing the Opportunity

The lot’s appeal was twofold: It was located right on the town’s main stretch and it was zoned for mixed use. “From a planning and zoning standpoint, it was a fantastic opportunity,” says the architect and urban designer, who also heads his own practice, the Vite Collaborative. (Or, as he describes it, “A bunch of friends working on unique projects together.”) If for nothing else, Vite purchased the property at a propitious time. The shops along Main Street had been expanding in that southern direction in recent years. Thus, Vite had originally designed the project as a residential spec home with the option for retail or commercial space on the ground floor.

While the sliver of land overlooks the principal artery of town life on the Main Street side, the opposing end couldn’t have more different surroundings — a quiet residential street with community gardens across the way. “From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building,” Vite recalls. “Both facades relate to the context of the side they are on.”

“From an architectural design proposition, that was very exciting to see how you could work this with two faces of the building.”

Yet another challenge the building site posed was the 10-foot grade change between the two frontages — an entire story difference, front to back. That was not all. The town’s zoning laws required a 5-foot setback from the property line. The house could be only 15 feet wide.

Fortunately, the neighbor’s garden to the south and a driveway next door to the north give the narrow site extra breathing room. “It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light,” Vite says.

"It’s true, it’s a very constricted site, and the response was a very long, narrow building, but it’s still flooded with light."

Unconstrained creativity on 15 feet across

The building constraints — the narrowness, the contrasting major facades, the steep slope — only spurred Vite’s imagination and inspired innovative solutions. How did he create a modern living space — an entire three-story house — with 15 feet (4.6 m) across to work with? The architect’s answer was a structural steel frame, an element adopted from commercial construction, which gave him the structural freedom to engineer large open spaces on the inside. “It’s a steel moment frame structure with three beams that go all the way down the building. Then there is a steel beam across the top.”

The steel beams manifested what would become part of the narrow house’s legacy, and with it, a close relationship between Vite and the local builder, Brian Beckett. “When he was erecting the moment frames, Brian called me and said we can’t put the roof on tomorrow,” Vite says. One of the moment frames had been a quarter-inch off plum, which was still well within building tolerances. As might be expected from the sanguine architect, the holdup was anything but a point of contention; on the contrary. “To have a guy who takes this that seriously was just really important to me. I knew I was going to get a great building from him,” says Vite. “The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

“The main draw to this project was the relationship I developed with the builder. It became evident early on that he cared about craft. We’ve become great friends.”

Actually, there was one moment during construction that did stop the architect in his tracks. After Beckett put the roof on the now-perfect steel frame, he took a picture and sent it to his client in Denver. “It looked like a tube; like you wouldn’t ever want to live in anything like it,” Vite remembers his initial reaction. “It wasn’t until we started finishing it out that it turned into what we’ve got. But that was a scary point, because it was so narrow.”

Family first

By the time construction was completed, the next ski season was approaching. Vite and his family had frequently driven up from Denver to ski in the Vail Valley during previous winters. “We decided we would use the house for that ski season,” Vite says about the investment property he had just finished. “We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

“We spent that ski season there. After that, we didn’t want to lose it.”

The unique house itself wasn’t the only reason the family never wanted to move out. “We absolutely fell in love with Minturn. It’s the real authentic mountain community between Beaver Creek and Vail, where you have all these people who are transient and vacationing. The people in Minturn are really the ones who keep that valley going,” says Vite about the mountain town’s thousand or so residents.

What’s more, Borges not once considered her husband crazy for building this improbable house. “We’ve been married for twenty years,” Vite laughs. “She is used to that.” And attuned to narrow dwellings she was. The first home the couple restored and lived in together was a townhouse in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood that was only 14 feet wide. “She’s getting an extra foot,” Vite exclaims, insisting his wife was thrilled about the idea to keep the Minturn house. Now the four escape up here nearly every weekend, year-round, to fish, drive their go-kart, hike — or ski in winter.

Open space to monkey around

Since completion, the house has evolved into a fun destination in its own right for the adventurous family. “The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open,” Vite says. Scarcely any interior walls partition intimate bedrooms and private bathrooms from the open, free-flowing floor plan. At the bottom, the concrete foundation encases a below-grade guest bedroom and bathroom on the dwelling’s Boulder Street side. Because of the steep slope, the opposite end is above ground, where the garage faces Main and can be extended out to the street for a future retail space.

“The narrowness drove the whole architectural design in choosing a steel frame so that the interior could be completely open.”

The ceiling of the modern living room on the second floor rises two stories with an overlooking loft, the parents’ open bedroom. The boys’ west-facing bedroom is tucked behind the “master” (or in front of it, depending on which frontage you interpret as the face of the house).

The family spends most of their time together in the open living space with the curved white couch. “We take this big picture off the wall and project movies onto the wall.” The cork-floored main living area flows outside through a folding glass and steel wall that opens up to the deck. A minimal dining area in the middle transitions into the kitchen, Vite’s favorite spot in the house.

“But what the kids love is this 26-foot space here,” says Vite, pointing at the high living room ceiling, where he mounted a climbing rope. “They get to climb up this wall that’s all blocked with wood, ready to put in finger holes for a climbing wall.” Climbing is indeed the boys’ favorite indoor pastime. “They climb everything they can get to,” their father reveals, pointing to a trolley that runs down the steel beam under the roof above the master loft. “You can strap yourself onto here and then push off.”

In addition to providing a place for the family to escape the city on weekends and holidays, Vite wanted to set the stage in the house for a few cherished vintage pieces he inherited from his late parents. “The interior design was all about finding a home for my father’s old furniture he had bought in the early sixties in New York. It’s all authentic midcentury-modern furniture, and I designed the interior around it.”

Sustainability as style

The LEED-accredited architect is reluctant to categorize the architectural style of his idiosyncratic house. “What they call it up here is a contemporary mountain home, because it very much has the feel of a timber frame, although it is done in steel,” he says. “But rather than talking about a style, the sustainability feature is more important to me.”

From the construction standpoint, the house is based on a standard wood module to limit material waste, which actually got Vite in trouble with one particular Minturn resident. “There is a guy up here who goes around the construction sites, picking up wood waste for his wood-burning stove at home. He would complain that we didn’t have enough wood waste and gave us a hard time.”

The carefully calculated use of exterior wood is to protect the building from driving rain in support of the actual weather barrier behind the wood. “All these gaps are open,” Vite shows. “It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.” Air exchange is critical for a highly insulated house at this altitude, where the air is extremely dry. “You are living and cooking and doing all these things that increase the humidity inside the house,” he explains. Instead of trapping the warm, very moist air inside, the house can breathe it out. Vite also installed a heat recovery air exchanger that pushes warm, inside-air to heat colder air coming in to ventilate the house, without using the heating system.

“It’s like the house is wearing this jacket. The wood is there for added protection, and the jacket breathes.”

Vite received the 2013 Award of Citation from the American Institute of Architects for this project.

Tight house, tight Community

Being awarded such a significant professional accolade from AIA is nice, sure, but what truly warms the architect’s heart is how the locals perceive the standout structure they’ve come to call the “skinny house.” “We get compliments on it all the time. People are stopping by, saying they’ve watched it go up and want to look at the inside,” he says. “I love that the town loves the house.” △

“I love that the town loves the house.”