Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

My Source of Architecture

A structural impossibility impels Colorado architect ml Robles to deconstruct her design and rethink the source of architecture. Surrendering to the house’s revelation ignites a deeper means to practice her métier.

Our finite world evaporates every single day as the dusk we have learned to overlook withdraws the light and dissolves form, transforming the day to night. The infinity that is our universe begins to appear, one star at a time, until the lid of our blue atmosphere evaporates and we enter the continuum within which everything exists. In this big picture, the earth holds its finite position for only a blink. In that blink, we build, but it is in the infinite continuum that architecture is sourced; from there a vibrating intelligence strikes our ideas with intuition and inspires our thinking.

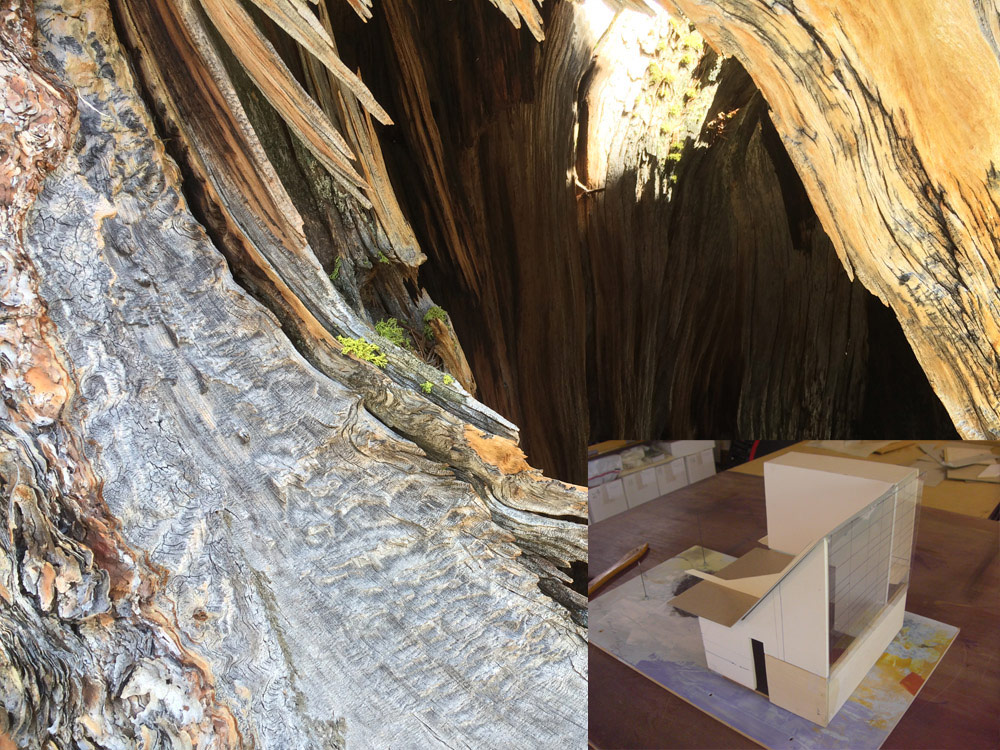

This is why some places make us feel so profoundly alive. I seek those places, I want to stand in spaces that make me fall to my emotional knees, I want to feel light pulsing through my veins, I want to be so profoundly anchored in place that time stops and space expands. I want that here, now. To get that, as an architect, I must look directly into the source and accept those unnamable vibrations that ignite intuition and spark inspiration. I must be willing to step into the unexplainable and know it is undeniable.

The power of constructing

My exploration into the source of architecture begins with a small group of deer, three, maybe four, that stood puzzling at the edge of the upturned earth where the craggy foothills’ belly lay gouged open under the pure blue Colorado sky. Violent excavation into the land is the first in a chain of aggressions made when we build. I was stunned silent when I came upon that small herd of deer staring into the gaping hole where waving grass had clung just hours before. The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning. Watching those deer reconsider that site was burned deeply into my architectural thinking, for that is what we architects do: We alter what was. This realization was one of my first steps into the source of architecture: Respect what exists.

"The power we assume in constructing is never more apparent than in the destruction that marks the beginning."

Working with what is

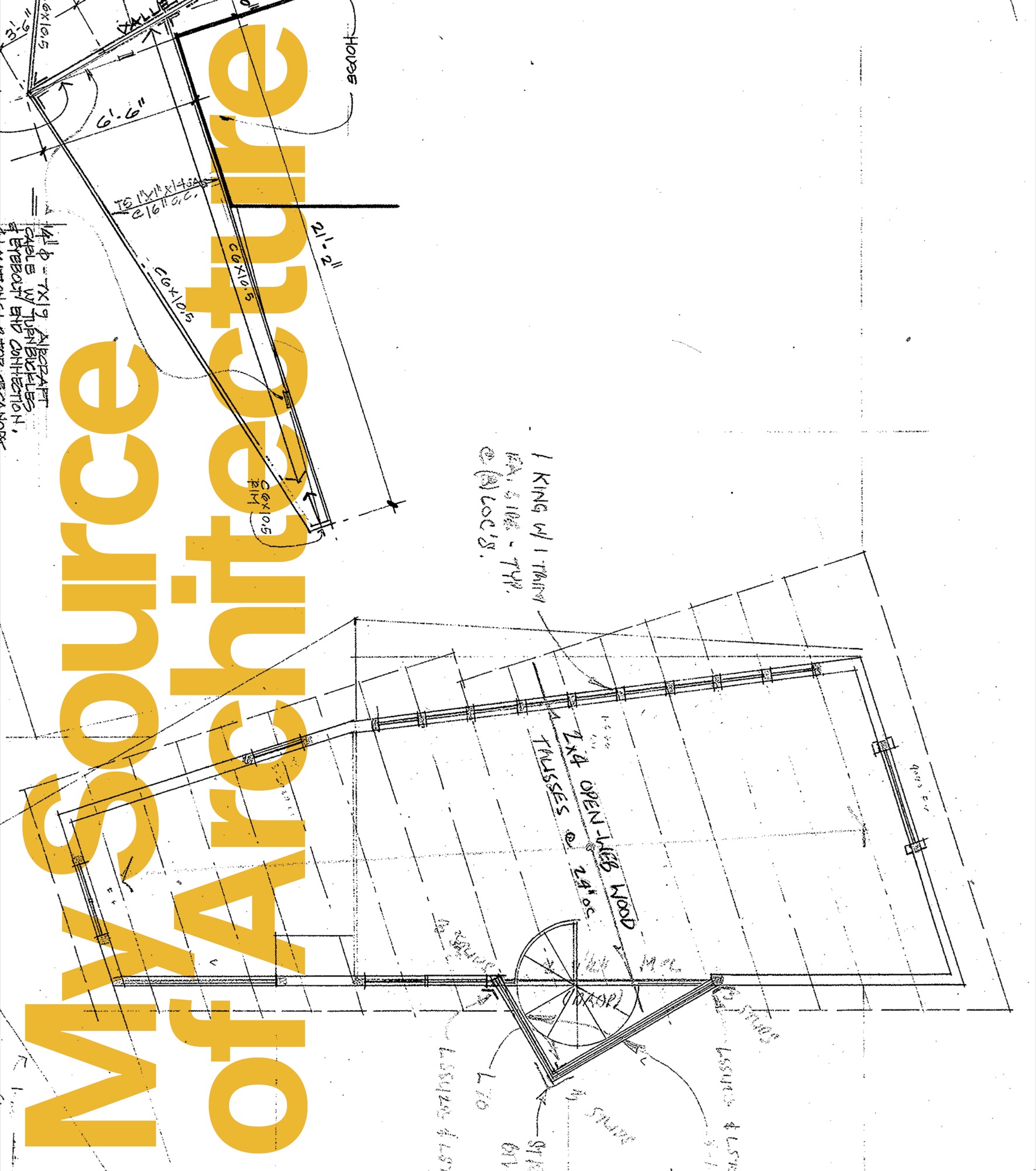

The small ranch house would have been a scrape-off to most sensible people. The builder and I, however, decided to work with the house and its detached garage, more from a perspective of “There is nothing wrong with its structure; let’s reuse it,” than any nod to its intrinsic qualities. The site was one of those hidden jewels in a nondescript part of Boulder, Colorado, that backed up to a parkway where the deep drainage ditch in front of the house made its way into a local watershed. Beyond that open area was a spectacularly clear view of the foothills curving along the horizon. I proceeded with designing a two-story, 3,500-square-foot (325-square-meter) house around, on top of, and including the existing ranch. It was all perfectly usual until the soils test, required to verify the capacity of the earth to carry the structural loads, said otherwise. The existing foundation would be unable to carry a second floor. The soils test is usually a nonevent, done for confirmation of what is already suspected rather than to dispute anything; this one, however, told us we needed a new foundation. We may as well have demolished the existing house since the newly recognized structural requirements were going to severely deconstruct the house.

Going up

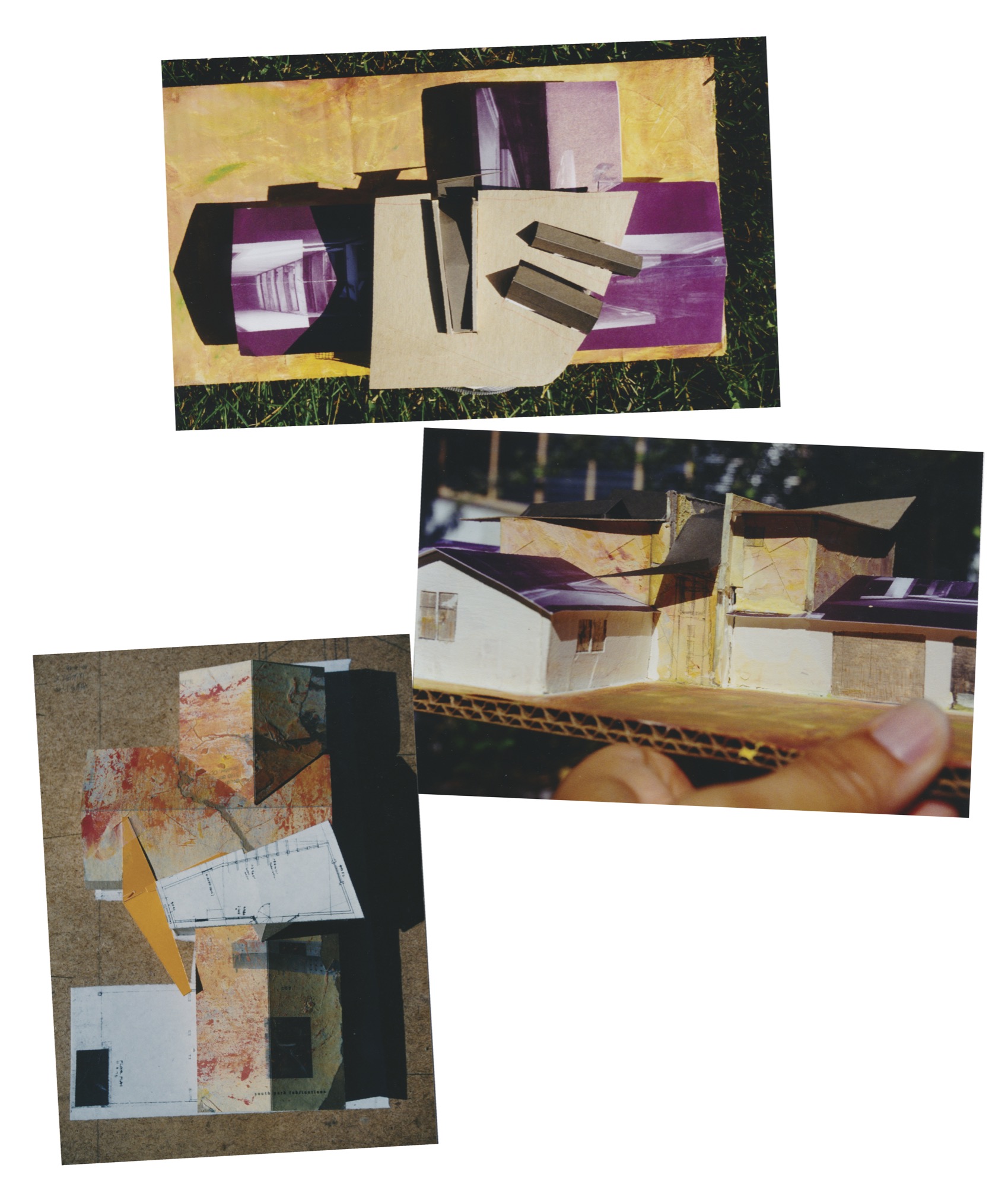

I sat with the cardboard model I had made of the house and garage. I had taped a collage of photos showing the magnificent view of the Flatirons—Boulder’s dramatic vertical rock-slab backdrop—onto the west edge of the model and was overcome by an insistence to build a second floor on that site to capture the view. Short of demolishing the existing house to build a proper foundation, I had to find another solution to going up. After wrangling with structural concepts, I sat down with my engineer and, using the model to illustrate, reasoned that if a tree could go up and out, why not a building? We would solve the problem by placing two piers between the house and garage to avoid disturbing the existing foundations, and then span back and front with steel beams to new foundation walls away from the existing structures. The framing spread over to the existing buildings, maintaining all the structural loads from the new construction to bear onto the two piers and new foundation walls. Like a gopher poking his head above the ground, the new two-story tower shot up from between the house and its garage structure with a spectacular 360-degree view.

We expanded the existing structure—both house and garage—to accommodate the new house with its tower shooting from the center. The only glitch was that the existing roof drained directly into the side of the new tower—a complete construction no-no, since the snow and rain draining off that roof into the side of the wall would eventually corrupt it. The standard way to deal with this is to build what is called a “cricket,” or hip roof, which is overframed on top of the existing roof at the wall intersection and stretches across it to lead water off to either side. This is what happens when construction creates a messy situation: The problem area is spirited away by trim false ceilings, overframing, and any number of other standard methods.

As I fiddled with that cricket roof on my model, imagining the tide of floodwaters raging against the tower wall, I became mesmerized by the idea of flowing water with its dancing light. What if we could experience that dancing light inside the house rather than scuttle it off the roof in obscurity? I was washed away with the inspired notion that we might be able to see this display of water.

What I resolved was to build a glass gutter—basically a slender inverted fold along that roof-wall intersection, furthermore sloping the whole thing to shed the water to the front of the house, right to the front door. I would capture the water in a big inverted wing that was anchored to the house roof on one side and flew into the sky on the other, creating a sheltering entry canopy. At the center seam, the low point of the inverted wing catching the water from the glass gutter, I sliced a gap and inserted a perforated sheet of weathering steel whose rust is managed in its composition. The rush of flowing water would fall through the perforations and drain into a gravel bed leading to the deep ditch along the front of the house. Mimicking nature, the water’s instinctive rush to the low point would be magnified, as in a waterfall with all its sparkling, glistening effect as it shoots to its destination. “You cannot build that,” they would say about the glass gutter. The big entry wing was less mystifying, and the weathering steel apparently not an issue at all as it was seen to be decoration.

Inspiration down the gutter (in a good way)

This would not be the first or last time I would hear those words, you cannot build that, but I could so clearly see the effect of the glass gutter on the inside of the house that there would be no turning back. Lucky for the house, the builder was also the owner, and he trusted the inspired gutter to deliver what was proposed. The house was built out with the kitchen spilling over into a dining area and outdoor patio and a living room with a face of windows articulating views of the Front Range—the eastern view of the Rockies. A see-through fireplace connected the living and dining rooms. Two bedrooms, a bathroom, and play area made the house family friendly. In the master suite, ceiling slots caught the glass-gutter reflections. A winding staircase led up to the tower room, which featured a sloping roof that jutted out to create shading overhangs for the wall of windows. We hosted an open house to celebrate the project and activated the glass gutter with a hose pouring onto the roof. Our “ship” launched with a cascade of water sheeting down the steel panel as the guests squealed with delight.

Over a decade later, I received an email from the latest owner of that house who had traced me through another house I had designed. This was the best house he had ever lived in, he wrote, and after living there, they discovered “wonderful, wonderful details,” such as the moonlight falling through the series of skylights.

When I read that note, I realized that I had never even considered the possibility of the moonlight casting onto that glass gutter and delivering itself through the ceiling slots. Astounding what shows up when unhindered inspiration leads to such unimaginable largesse. Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence.

"Making architecture is never a linear journey, less so a totally rational one, as the journey traverses land that always has a unique story and an atmosphere filled with a vibrating intelligence."

Listen to what shows up

I have learned to embrace the marvelously unpredictable environment of design by working with physical models that take me out of my rational, calculating mind and drop me into an intuitive, three-dimensional state. Thanks to this project I got my second step into the source of architecture: Listen to what shows up. In this case the failed soils test and cricket roof changed what would have been an unremarkable construction into one that is able to lift the lid of our blue atmosphere and connect us to something so much bigger, something we might never have imagined, like the moonlight casting through the slots, awakening our senses and imaginations even more.

It is said that the dream is realized where the dream is sourced. If we do not dare to dream, to touch something within ourselves that ignites our passion, we will never see that dream realized. This certainly seems to be the case with places that make us feel fabulously alive—they touch something within us that we may have only known in dreams. And that is why, above all else, in the little blink we have on our finite earth, I am an architect. △

* * *

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently completing her first book in which she tells the story of how she came to be Under the Influence of Architecture.

Nature Is Architecture without Enclosure

Why Alpine Modern has a brief cameo in ml Robles' upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"

From my upcoming book "Under the Influence of Architecture"...

So much of architecture is about replacing what exits. We remove buildings or parts of them, we scrape off land. We like new.

Then we get immensely attached to the buildings that have weathered throughout centuries. Think, Venice or historic buildings like Monticello or Westminster Cathedral. And we want to preserve them, not change a thing.

This is the discussion design enters into when we begin the critical examination of a project’s circumstances: What actually exists? Although the direction that is uncovered in the partí—the basic concept of an architectural design—holds both the physical and ephemeral, it is innumerate. Design, therefore, is a process of uncovering and illuminating the exact constructs necessary to meet the partí. And this is where the eye of the beholders produces the endless solutions to any given design problem. (Put another way, this is also where all hell breaks loose, for who is to say when a partí has been met?)

If architecture begins at the beginning of everything, and it is guided forth by secrets that cannot be told within the mind alone but are revealed by light, then it would seem that in order to uncover and illuminate the exact constructs necessary, design would have to continuously trace back to origin, to tapping the feeling that instantaneously shoots into the infinite.

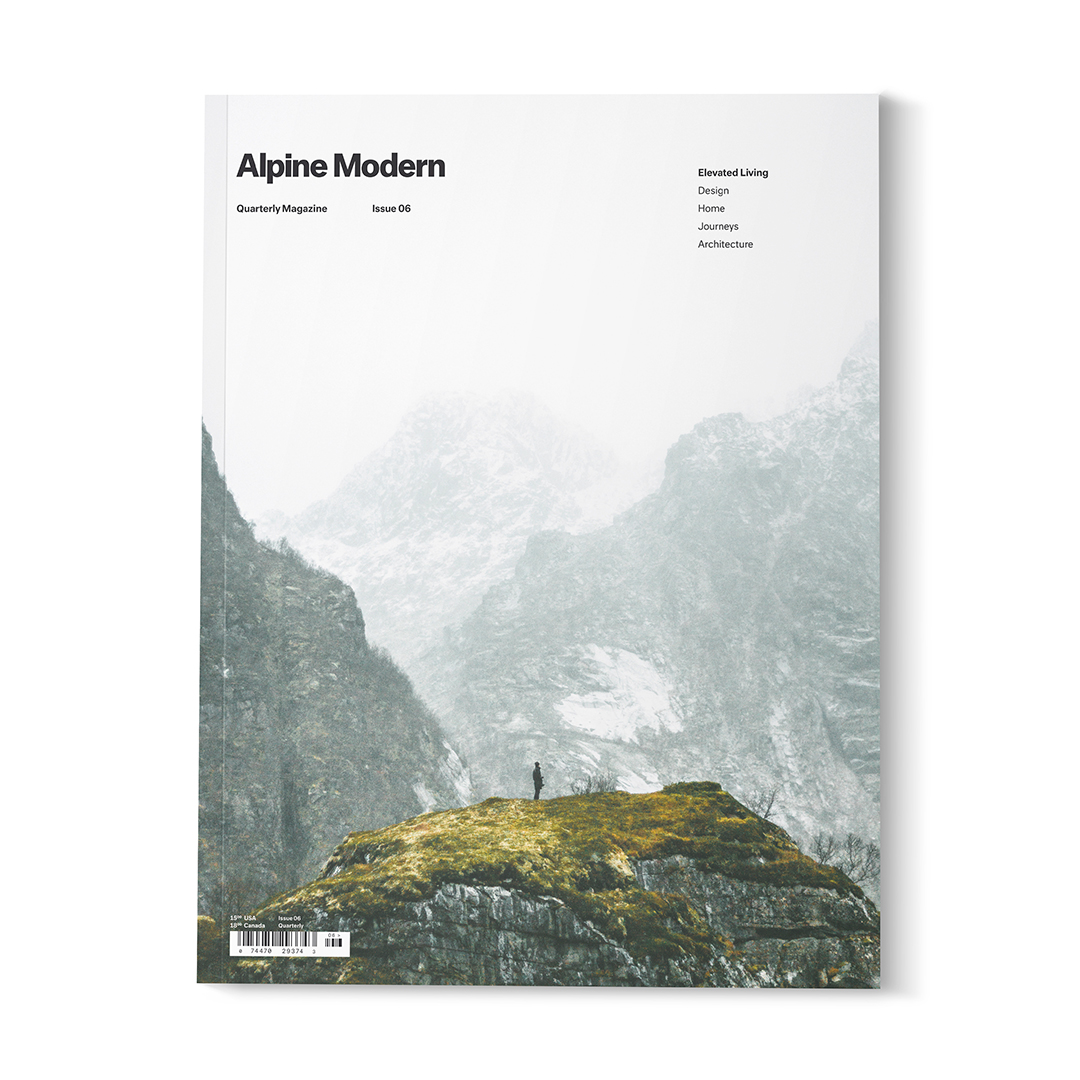

There is an image on the farewell cover of Alpine Modern’s print magazine. It is an image that fades from a near-white mountain backdrop to a dark silhouette of a lone person in profile standing on a mossy green capped rock. I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure. △

"I stare at that cover often because it describes everything architecture is, without a shred of enclosure."

When not practicing architecture or creating singular built environments at her research-based firm Studio Points in Boulder, Colorado, ml Robles explores the source of architecture in her writings. She is currently writing her book "Under the Influence of Architecture."