Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Landscape, the Architect

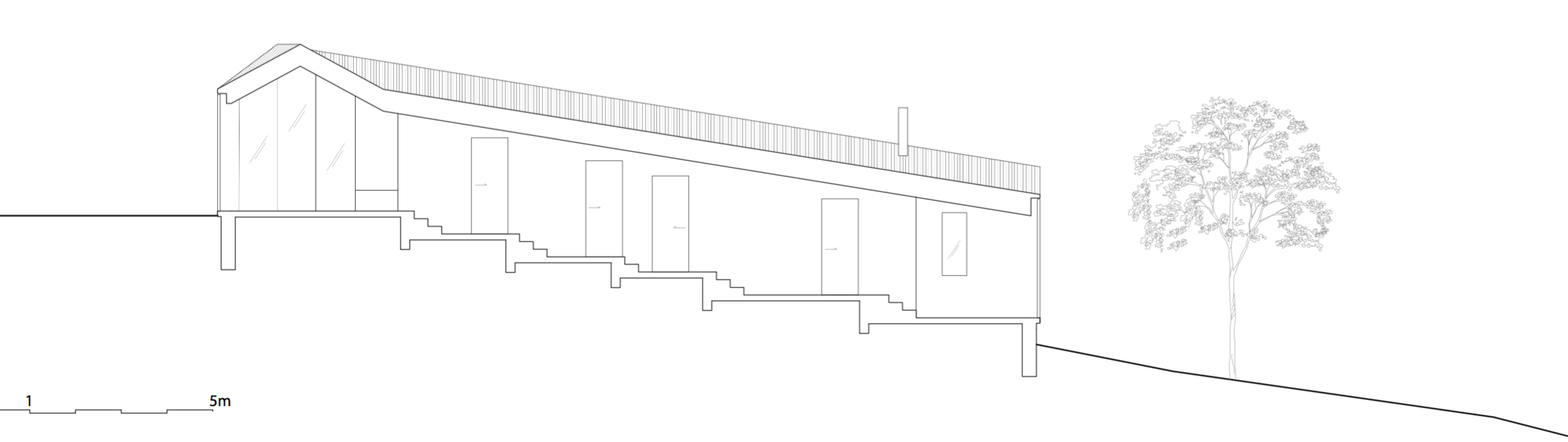

The calm design of the V-Lodge in Norway responds to the down-sloping terrain

High up in the mountains of Norway, the V-Lodge's simplicity in design and choice of materials speak to its wild surroundings. “The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal,” Oslo architect Reiulf Ramstad says about the minimalist mountain house he designed for a family of six. “Its form is a dialog between the landscape and the client.”

"The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal."

Ramstad’s architecture speaks to the people and the place he creates it for. The self-described generalist, who designs modern homes as well as hotels, churches, and civic projects, says today’s one-size-fits-all designs may be rational, but, “Architecture is more than an economic business; it’s a humanistic business. The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals.”

Creating only what is essential, never more than necessary, particularly interests Ramstad. The V-Lodge a prime example: His clients, who enjoy nature and simply being together, away from their busy lives in the city, had originally commissioned a much larger house to be built on their land 200 kilometers (124 miles) northwest of Oslo. Discussing the project with the architect, however, they understood that a smaller, more sustainable cabin would better suit their needs and accommodate a change in family composition and a mix of generations in years to come.

"The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals."

The Right Man for Wild Territory

“We had found the most beautiful site on the outskirts of the Norwegian mountain area called Skarveheimen, a wild territory between the better-known and -visited Hardangervidda and Jotunheimen,” says Lene, who shares the remote retreat with husband Espen, their three grown children (twenty-two, twenty, and eighteen years old), and their eleven-year-old daughter (“our afterthought”). Plus, not to forget, labrador Vilma. (The family prefers we do not print their surname).

The couple had searched for the right architect for quite a long time. “Someone who could gently transform the landscape and, at the same time, preserve and strengthen the qualities of the site,” Lene says.

Influenced by two very different cultural contexts—Scandinavian and Latin—the Nordic architect’s business and design philosophies made him the right man. Born in Oslo, Ramstad, who received his Dottore in Architettura from the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, deliberately chose to study in Venice, Italy, to experience life without cars. He founded Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter in 1995, without previous experience. He has never worked for another firm. “It may not be the most rational way, but it’s a very interesting experience in that you have to invent most things,” reflects the credo of the now internationally recognized architect.

Lene, a graphic designer, and Espen, an executive in the gas and pipeline industry, handed Ramstad a long list of functional needs and aesthetic preferences along with a budget, but otherwise, they gave him free hand. “We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking,” Lene says.

"We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking."

Walking the Landscape Inside

The remote retreat sits near timberline at 960 meters (3,150 feet) above sea level, high above spread-out villages down in the valley. The architect took his own site survey, obtaining more precise data than the public maps revealed. “We needed finer measurements so we could create a better dialog between the building and the landscape,” Ramstad illustrates. “The building itself can follow the topography, instead of peaking and ruining the place.”

Guided by unspoiled mountain views and the directions of the wind and the sun, the V-shaped house design is Ramstad’s response to the landscape. While one side of the V sits on a horizontal level, the other side steps down with the terrain, resting close to the ground. “You can walk the landscape inside the house,” says Ramstad. The small scale of the rooms in this private wing reflects nature’s small scale right outside the windows there — small plants and trees, the snow lying close to the ground. “It’s a very simple way of responding to different scales and intimacy, to public and private spaces.”

"You can walk the landscape inside the house."

The horizontal wing of the 120-square-meter (ca. 1,300-square-foot) house accommodates the entrance and the main living area with the kitchen and the dining room. The other part, which follows the downward slope, houses the bathroom, three bedrooms and a lounge area at the far end. The V culminates with the glazed wall at the confluence of the two sections.

A Spatial Kaleidoscope

Ramstad’s design uses only about a tenth of the land, letting the rest be nature. “Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature,” Lene says. “We are carefully taking the terrain close to the cabin walls back to what it was, as if the cabin is growing out of the ground. Working with soil, stone, and vegetation is part of our life at the cabin.”

Ramstad perceptively oriented different elements of the structure toward distinct sights, offering views of different kinds of landscape. “The architecture is a spatial kaleidoscope,” he says. The floor-to-ceiling walls of glass create immediacy with the outdoors. “The glass cancels the barrier between inside and outside,” the architect continues. “Sitting in the living room is like having these huge landscape paintings that are actually views towards the mountains. So working with very subtle and slim glass details and without frames, the window becomes just a transparent layer, and not a window in itself.”

"Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature."

The exterior is entirely clad in untreated, short-hauled pine; inside, walls and ceilings are paneled in pine plywood. “Using one material gives wholeness,” Ramstad says about the lodge’s minimalist appearance, which is also void of extra decorations. “When the wood oxidizes, it will have this patina that blends into the landscape, into the colors of the surroundings. The design and carpentry of fixed furniture and other features, including lamps, kitchen, bathroom, wardrobe, tables, and beds, was done by the owners themselves. Says Lene: “We like to design and build things together, and that is an important part of our leisure time.”

100 Days of Solitude

“Going to the cabin for weekends and holidays is definitely different from our life in Asker by the Oslofjord. A three-hour drive from home, and we are at the cabin, where we have everything we need for recreation — but not more than that,” Lene says. “However, the most important thing is being together, and at the same time having the freedom to be on your own.”

In winter, the family cross-country skis right out of the cabin’s door. In summer, they hike in the surrounding mountains. On warm days, they go for a swim in the nearby mountain lake or a dip in the River Lya. “This has definitely become the all-year cabin we wanted,” Lene raves. “We used it exactly 100 days the first year.”

The architect is equally pleased. “Spatially, this is not a very fancy project. It is very calm, yet at the same time, has very clear, distinct design solutions,” Ramstad says. “I’m very happy with it.”

V-Lodge Photo Gallery

Extreme Shelter

Living ecological alpine pods in the Italian Alps

Test laboratory mountains: The Italian architect duo behind LEAP (living ecological alpine pods) design-builds modular solutions for harsh high-altitudes. Luca Gentilcore and Stefano Testa, founders of LEAPfactory, Turin, Italy, share a strong passion for alpine adventure and avant-garde architecture. “We love exploring the limits in both fields,” says Testa. “LEAP, to us, represents quality of life and a love for nature, particularly pure nature, and the devices humans build to survive — may these be sweaters, camping tents, or high-tech buildings. We do not limit ourselves or our activities.”

"LEAP, to us, represents quality of life and a love for nature, particularly pure nature, and the devices humans build to survive — may these be sweaters, camping tents, or high-tech buildings."

The mountains are their test lab. “The extreme conditions, the essential dialogue with a marvelous and strong nature, the loosening of human rules and customs — all this makes mountains the best setting for focusing our goals.”

Both men are avid mountaineers. “The mountains are where I feel free, and nature is the vehicle to look for the deepest sense of life. I spent thirty years of my life rock climbing around the world. I climb less often now; it’s still the best way for me to have time to breathe deeply and to find my balance,” tells Testa. A perfect day? “Climbing a perfect sequence of beautiful holds on a sunny rock wall and, at the end of the day, a dinner around the fire with my family and friends in a clearing, the scent of tree sap in the air.”

Continues the architect, “After many years of studying, practicing, and teaching architecture, LEAP is a way of bringing together my two souls — nature and artifice, technology and beauty. This is the path of LEAP design research.” Testa studied the masters of modernity, the Italian tradition of the fifties, and the radicals' tenets of the seventies. He also worked with contemporary artists. “All these things influence my work today,” says Testa, yet he adds, “I love to think there is not one design style in my work. Instead, there is a continuous search for the right answer to specific questions and places.”

"After many years of studying, practicing, and teaching architecture, LEAP is a way of bringing together my two souls — nature and artifice, technology and beauty. This is the path of LEAP design research."

To Gentilcore, the mountains have meant different things throughout different periods of his life — fun, exploration, culture, relationships with the force of nature and with other people. “The mountains for me evoke these emotions that have the power to remove the filters contemporary society imposes on us. In that sense, the mountains have become a fundamental component of life for me that I can't do without.” Last summer, Gentilcore hiked with his wife, their two children, and a donkey through the wild landscapes of the Massif Central in France for fifteen days. There, I felt really happy.

"The mountains for me evoke these emotions that have the power to remove the filters contemporary society imposes on us. In that sense, the mountains have become a fundamental component of life for me that I can't do without."

Respect for the mountains is innate for Gentilcore. “It's respect for nature itself and the culture that the mountains represent. I think this sentiment is originally part of all of us, but it is often clouded and hidden.” It has helped him discover how efficiently humans and nature respond to extreme, hostile environment. “To design for the mountains, we need to study successful sustainable solutions we can adapt to urban and ordinary contexts in the future.” He’s inspired by fields other than architecture that offer alternatives to the traditional way of building. “For the Gervasutti project, for example, we looked at aeronautics and boating; other times we have turned to the world of high-end furniture. For this reason, our projects are almost always new construction systems or new building types.”

Nuonuova Cappana Gervasutti, Mont Blanc, Courmayeur, Italy

Gentilcore and Testa relish untouched alpine nature. But if they do put a dwelling on a pristine peak, blending in isn’t the program. Above preservation, the designers aim to enrich the diversity and quality of an inhabited, inherited landscape.

Hence, when the Turin Alpine Club commissioned the new Gervasutti hut under the east face of the Grandes Jorasses in the Mont Blanc massif, the architects proposed what they now call “an ambitious solution.” It worked. “The site is very complex: a very small terrace on a rock buttress, in the middle of Freboudze glacier,” Gentilcore describes.

Rethinking the relationship between humankind, nature, and artifact, the two gave rise to a new generation of alpine bivouacs: an entirely prefabricated modular shelter that is airlifted by helicopter to its remote location and installed in only a few days, with minimized endeavor and without permanently altering the sensitive hosting place. “Modular design is a technical strategy to minimize the necessity of construction work on site. This is fundamental in fragile environments — and for our approach of ‘living in nature on tiptoes,’ ” says Testa, who has a PhD in interior design and has taught interior design and architecture and urban design at the School of Architecture of the Politecnico di Milano and industrial design at the New Academy of Fine Arts, also in Milan.

Transporting the new Gervasutti refuge by small helicopter to its installation site, high up between Haute-Savoie in France and Aosta Valley in Italy, was a lofty feat. “The typical aircraft used in mountain regions can load around 800 kilograms (1,764 pounds) up to 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) above sea level, so we realized four modules, entirely equipped, within that weight limit,” Gentilcore says. “At the same time, we had to guarantee very high mechanical resistance, due to the extreme environmental conditions. After several tries, we got to the final solution with an innovative prototype of a fiberglass shell.”

The high-tech tube thoroughly redefines the model of the traditional alpine bivouac built for survival, not comfort. “With the Gervasutti project, we aimed for something between a bivouac and a refuge,” Gentilcore says. “The comfort comes from cutting-edge technology, much like with contemporary mountain gear and clothes. But its environmental footprint is way lower than that of a refuge.”

"Modular design is a technical strategy to minimize the necessity of construction work on site. This is fundamental in fragile environments — and for our approach of ‘living in nature on tiptoes."

Stand-out Design

Gentilcore, who graduated cum laude in architecture from Politecnico di Torino in 2004, says much has been said about the aesthetic impact of the Gervasutti. “We thought, in the glacier landscape, there is no building tradition. And we didn't follow a mimetic approach relating to the strong natural environment. We designed a technical shape, and the shelter became an extraneous presence in the landscape.” The visual statement was purposive, beginning with the colors — white like the snow and the ice and red for visibility. The pattern is an homage to the traditional mountain sweater and, not least, part of LEAP’s corporate design.

Gentilcore interposes, “We also have to say that the circulated photographic portraits of the Gervasutti are completely different from the tiny, diminishing presence of the building when observed in person in the surroundings of this majestic landscape.”

The new Gervasutti shelter has become a hiking destination. “Last year, more than 600 people signed the hut book,” says Gentilcore. “Before our installation, the Freboudze valley, one of the most beautiful valleys on the Italian side of the Mont Blanc massif, had just twenty visitors per year.”

Founding Leapfactory

The partners reveal that the research and resources they invested in the Gervasutti project were utterly disproportionate to the realization of a single building. “We decided to found LEAPfactory and to develop a special building system, the LEAPs1, to commercialize it,” Gentilcore looks back. The year was 2013. The s1 was the first LEAP product.

The living ecological alpine pods are completely reversible by design, an essential ecological benefit of the s1 system. No concrete foundation. No ground alterations. “It leans on legs anchored to the rock with bolts,” Gentilcore explains. “Working at 3,000 meters of altitude is really hard — for the people and the ecosystem — so every activity on site needs to be minimized.” What’s more, by virtue of the extreme lightness of s1’s components, the number of required “heli rotations” (flights up the mountain and back) equals the number of modules. An individual module that sustains damage can be flown off site for repairs.

The modular structural sandwich–constructed shell, the quintessence of the s1 system, is made of a sophisticated synthetic composite compound, similar to materials used in manufacturing competition speedboats. An additional thermo-reflective insulation layer provides an advantageous microclimate inside the pod, even without a heating system. Warmth comes from thermal sources such as a cooking stove and even the inhabitants’ body heat.

A photovoltaic film integrated into the pod’s shell powers electrical devices. There is an Internet and a radio connection. A remotely controllable digital system monitors various functions of the s1, for example, energy autonomy, and provides information about internal and external weather conditions.

The configurable single-function modules (entrance; living module with kitchen, dining area, and pantry; sleeping quarters; bathroom) allow for flexible functional programs. “The big window at the extremity, ‘the eyelid,’ as we call it, transforms the building into a landscape-watching machine,” Gentilcore says.

Eco Hotel Leaprus 3912, Mount Elbrus, Caucasus, Russia

In September 2013, LEAPfactory installed an eco hotel for the North Caucasus Mountain Club as the first in a series of projects intended to encourage tourism in the region. LEAPrus 3912 comprises four tubes, built from prefab s1 modules, on the south side of Mount Elbrus, Russia. The refuge sits almost 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) above sea level along the standard route to the summit.

“The LEAPrus project was even more ambitious compared with Gervasutti,” Gentilcore says. “Fifty beds, a restaurant with kitchen, bathrooms with warm showers, heating in every room, a system to melt the snow to get water.” The hotel today operates year-round, hosting skiers in winter. “The off-grid functionality was demanding. We built a plant that produces energy from the sun and wind.”

Like the bivouac pod in Italy, the entire LEAPrus structure was installed in a few days, once again using helicopters. “We had less time than originally scheduled because all the operative helicopters in the region were in Sochi, busy with building the Olympic facilities. We remember the thirty-eight heli rotations over three mornings very well . . . and the evening of the third day, when our staff rested in our buildings that were just assembled and outfitted with electrical light, heating, and the operative kitchen,” says Gentilcore. “A super spaghetti party was organized, after many Russian soups in the construction barracks the days before.”

That night, Gentilcore slept right in front of the eyelid. “I will never forget this experience, the main Caucasian mountain range beneath me, in the sunrise . . . ”

Pod Lifestyle: LEAPS1 as Private Residence

Aside from the extreme conditions of Gervasutti and LEAPrus, Gentilcore says his company’s goal for the s1 system was to apply today’s best building practices, with particular focus on the ecological process. LEAPfactory has received many inquiries about the s1 as residential dwelling, although no one has realized it as tiny house or weekend cabin yet. “The LEAPs1 is a really sophisticated product, and it's quite expensive,” says the architect. “We can imagine s1 as an efficient off-grid house in a beautiful forest . . . with the ease of moving it to a new place.” △

Photos by Francesco Mattuzzi

Art ± Geology

A studio visit with modern painter Sarah Winkler

Contemporary artist Sarah Winkler’s experimental painting technique mimics the addition and subtraction of geological processes in nature. Iceland’s geological drama and Alpine-Nordic design ethos inspired her current winter series of fantastical alpine landscapes. It was a cupboard drawer full of Mars bars that lured Sarah Winkler into the world of art. She was five years old and lived in Manchester, England. The cache of hiking treats belonged to an impassioned artist living next door. Sarah and her brother liked to visit him and eat his chocolate. Eventually, the little girl became fascinated with the neighbor and his lifeway. The man had worked at a bank his entire life. But on the weekends, he would ramble across England and over mountains. In his seventies, even, he climbed in the Himalayas. “He was an incredible adventurer,” Winkler recalls about the former neighbor, who had most of his house converted into a studio. “He would sketch all his travels and come back and translate the sketches into detailed drawings.”

And that’s what Winkler does today. The British-born painter remembers being “absolutely captivated” by her childhood idol’s way of traveling and then documenting the things he saw along the way, his journey. “That’s who this guy was, and being around him was enough to start that bug in me, the love of travel and adventure and painting.”

The Travel Painter

Much like a travel writer brings back stories from afar, this wanderlust-bitten painter must travel to make art at home. “Experiencing new things, seeing things for the first time...you’re really open and raw, so you are absorbing a lot easier. I travel and then come back and work, based on the memory of that place,” she says. “I take vacations in search of solar eclipses, exploding volcanoes, or the northern lights.”

Just don’t call her a landscape painter. “I don’t want people to think I do nice little landscapes...of places that actually exist.” Her invented vistas disregard human imprint on landscape. They do, however, consider what landscape does to us humans. “These are wild, untouched spaces. They almost become psychological spaces.” Her scenes interpret the human relationship with the outdoors. Why do we go to the forest? Why do we climb mountains? Why do we hike trails? Why do we still go into wilderness this far into our evolutionary progress? “Sometimes, you have to go into the darkness of nature to really know yourself,” the spirited artist says.

Wild, untrodden landscapes mesmerize her. “The horizon line is this boundary between what you know, your reality as it is, and what you don’t know...what’s coming,” she philosophizes. “A strong horizon line signifies this moment when you’re going off the deep end, into an abyss. It’s that wanderlust kind of feeling of a journey, of traveling, of submitting to something challenging that you have to go towards and overcome.” Her art tells of survival in wilderness, accented by peaceful moments of pure consciousness in nature. “You forget all the humdrum of life, but at the same time, there is a fear factor. You have to be brave, Zen-like, and really present.”

A strong horizon line is the common characteristic in Winkler’s landscapes. That giant glaciers and rugged peaks, which inspired her current winter series, don’t typically make for an obvious horizon line doesn’t deter this willful woman. “Because the horizon line is very important to me, I decided I’m going to force a horizon line in these paintings, even though it doesn’t exist,” she says, eyes twinkling. What’s more, the ebullient blonde places the horizon line dead center. “That’s such a no-no in painting, I love it,” she laughs. “In abstract painting, the joke, the idea is that you don’t know which way is up.” Realistic landscape paintings, on the other hand, always have a definite top and bottom, a rule Winkler bends. “You can actually flip these paintings one way or the other and they will still read correctly as a landscape painting.”

"I don’t want people to think I do nice little landscapes...of places that actually exist."

Her make-believe horizon lines become a divide of above and below—the alpine reality we see above, all formed by a geology below that we can’t see. “It ties in with the Continental Divide here in Colorado. It’s very dramatic, two plates crushing together and mountains are growing,” she says. “It’s about landscape that’s growing, that’s forming, that’s eroding, that’s expanding.”

A Place to Paint

With a father whose jobs in aviation moved the family around the globe, the artist lived an adventurous childhood in Africa, where her mother first encouraged her to draw her unfamiliar surroundings, and later in different places across Southeast Asia. In 1989, the world-wandering family immigrated to the United States, where the expat graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in studio art, creative writing, and earth science from William Paterson University, New Jersey, in 1994.

The environment the transplant lives in is very indicative of her art’s colors and moods. Today, the forty-two-year-old lives and works in a three-story mountain home perched in an aspen grove at the summit of an 8,500-foot (2,591-meter) peak above Denver, in the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies. Husband Jason and their pooch also live in the matte black house with white trim.

In Winkler’s current body of work, the influence of her new mountain domicile converges with memories of a pivotal journey to Iceland. “A very geologically dramatic island...the colors, black and cobalt blues, and these very stark, surreal, empty landscapes,” she reminisces about the volcanically active country. The artist’s painted Nordic landscapes use neutrals and calming spots, an aesthetic she discerned during design week in Iceland. “They usually have pops of color or strong moments of interest, and then everything is quite calm and minimal around it.”

The worldly-wise Brit and her travel companions drove in Jeeps over glaciers, watching the northern lights. She photographed nature’s night spectacle with long exposure. Afterwards, the pictures revealed what happened between the aurora borealis displays. “I saw these very dark, cobalt skies, and then this amazing landscape in the middle was popping out, because the bright snow and the glacial moraines and the ice were overexposed, of course. So working from that imagery was how I came up with this winter series.”

Winkler’s landscapes, fantastical and abstract, don’t depict real places. The outlines of mountains aren’t existing ranges or peaks one could pinpoint on a map. Yet Instagram followers from Iceland instinctively recognize their own country when the artist posts snaps of her latest works on the site.

Rather than the likeness of real-life scenery she surveyed, Winkler wants to render the emotion a landscape evoked in her. “Working from the memory of those forms and colors and textures is how I came up with the sketches, and now I am translating them into really abstract paintings,” she says. The winter series draws on Winkler’s memory of Iceland’s Blue Lagoon in particular, where the artist bathed in the warm, otherworldly milky-blue water. “You have the black lava fields and the bright turquoise tide pools, and the ground is covered in the white silica minerals from the water.”

"This whole painting process is about adding and subtracting, like the erosion process in nature."

Each scene takes time to ferment in her mind. “Because I am not painting realistic scenes, nostalgia is always a little bit more interesting than what’s fresh in your mind, when you know all the details,” she says, admitting that forgetting a few details helps her get down to the essence of an experience. “Remembering only the most interesting part makes it this haiku moment in the landscape. Boom.”

Winkler’s creativity is fueled by a sense of place within her surroundings. At the time of her Iceland travels, she still resided in California—and painting icy Nordic landscapes in such an agreeable one-season environment felt incongruous. “Iceland was such an extremely different experience, a very Nordic, alpine, Arctic Circle kind of place,” she says. “When I came back to California, I couldn’t get my head into it. It was the wrong place to work on it.” She shelved the Iceland-inspired series. But when she and her husband relocated to Colorado in early 2015, the artist absorbed a wintry experience, and the alpine wilderness there that reminded her of Iceland’s rugged terrain. “That’s how these colors started coming back to me. It made sense now, and now it just owed out.”

"Remembering only the most interesting part makes it this haiku moment in the landscape. Boom."

Emulating Geology

Winkler at first experiments in ink on transparent foil, using the same solvents and resists she later uses with the paint media. When “something interesting” happens, she scans the plastic swatch, magnifies it, and prints it in archival inks on acid-free coated papers she then rips to pieces. Each landscape begins as a small collage made from those paper scraps. When I comment that these collages she calls her “sketches” are beautiful small works of art in their own right, the creative says this was indeed what she sold as her final pieces for many years. Only this year she began translating the collages into large-scale paintings. But could she simply paint a landscape that’s not copied from a paper-assemblage sketch? “I’ve actually tried a painting without any collage references, without any sketch reference at all, and it was a total disaster,” she admits. “The collage creates the look of a painting. This hard-edged torn-paper effect gives a very graphic feel to the painting. It’s very painterly, but it’s very graphic at the same time.”

"The collage creates the look of a painting, this hard-edged torn-paper effect gives a very graphic feel to the painting. It’s very painterly, but it’s very graphic at the same time."

Winkler’s final paintings are acrylics on wood panel. Each large wood board is first treated with a sealant and several layers of the artist’s own mix of ground marble dust gesso, and then wet-sanded between applications to attain a polished, ice-like finish. She works in stages, using different techniques in different sections, which she masks off. Her experimental approach involves solvents, resists, and carving tools to mimic geological effects in nature, such as abrasion, corrosion, sediments, wind ripples, pooling water. It’s yet another layer in her abstract interpretation of landscape. “It’s not just that I am painting geological textures. It’s digging deeper into the process of the landscape, because the minerals I use in my paint mixes, the marble, the mica, the iron oxide, all come from the rocks.”

"This whole painting process is about adding and subtracting, like the erosion process in nature."

Winkler immersed herself in the study of geology and quickly discovered that the colored pigments in her paints also come from crushed rock and the earth. “What if the pigments in the paint would do the same thing as rocks and dirt and landscapes do in nature?” The artist manipulates textured paint media with water, oil, salt, wind, heat, and sanding tools. “You apply a layer of paint, and then you take some of it away,” she explains. “This whole painting process is about adding and subtracting, like the erosion process in nature.” △

Photos by Christopher Mueller