Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

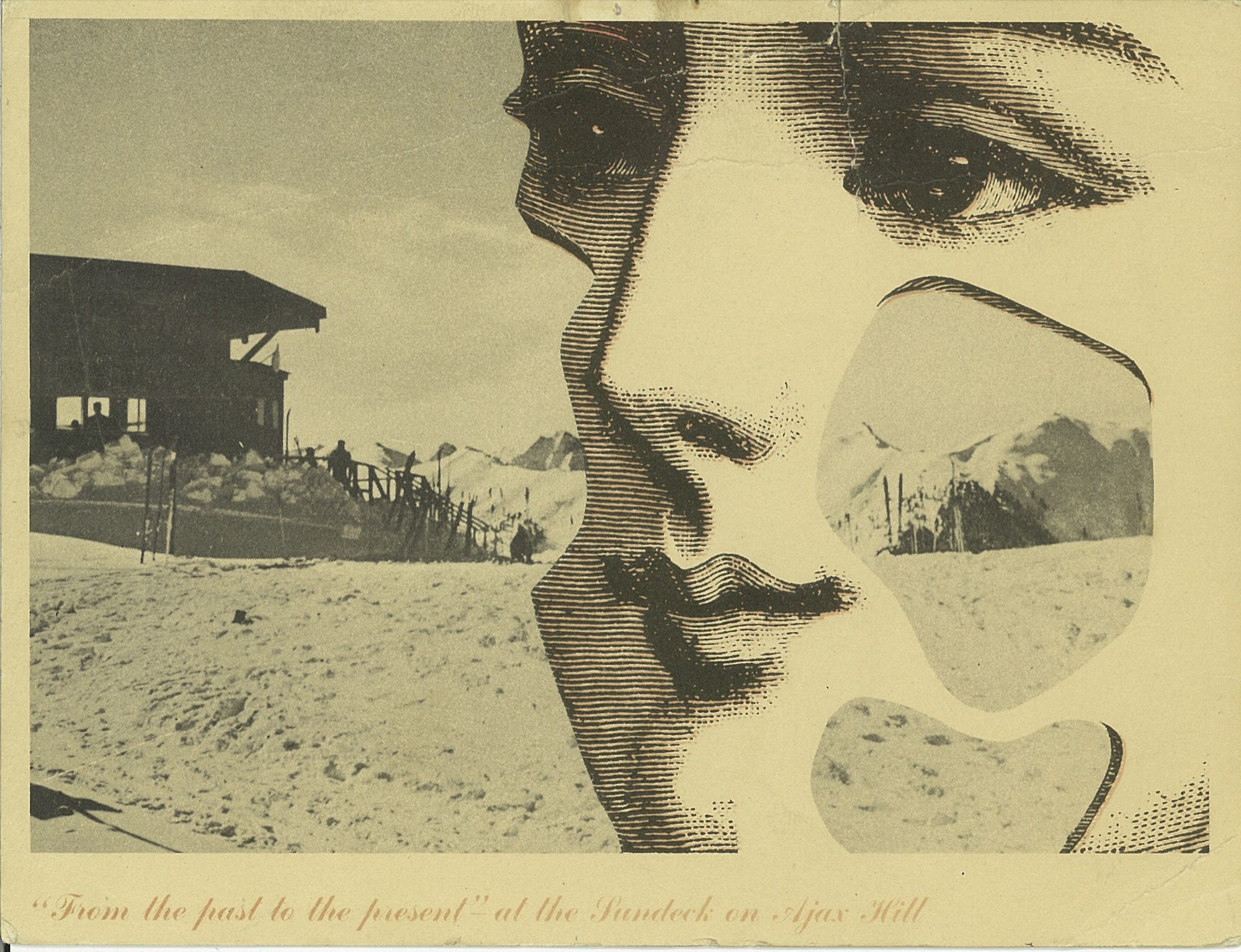

How American Modernism Came to the Mountains

A daughter of America's midcentury-modern movement remembers how Chicago’s design elite settled in Aspen, giving rise to modernism in the mountains of the West.

After World War II, Chicago’s design elite flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, galvanizing the then-sleepy alpine village with modern mountain chalets and avant-garde public buildings that helped transform Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley into the glamorous destination it is today. A memoir by artist Marcia Weese, daughter of Harry Weese, a central figure in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern.

Someone recently remarked to me that I was “born to design.” Over the years, I have come to appreciate this birthright, as I realize I have tenaciously and (mostly) joyously cleaved to the creative life, and still do. I have my parents, Harry Mohr Weese and Kitty Baldwin Weese, to thank for this. The creative life is not for the faint of heart, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Childhood in Chicago

It was the early 1950s in Chicago. As my mother told it,

“The war was over. No one had any money. No one had any furniture. Apartments to rent were scarce. We made do.”

When I was very young, we lived in a dim railroad flat in downtown Chicago. This was a typical inner-city apartment with a linear floor plan. The only natural light filtered through windows in the front and back. Chicago was a coal-burning city, and you could write your name on the window sills in the soot. I remember running down the dark hall that connected front to back, with crayon in hand. My parents encouraged my sisters and me to draw on the walls in that nondescript hall. What a great idea they had to spruce up the crepuscular gloom of the hallway, and how fun it was for us to break the rules.

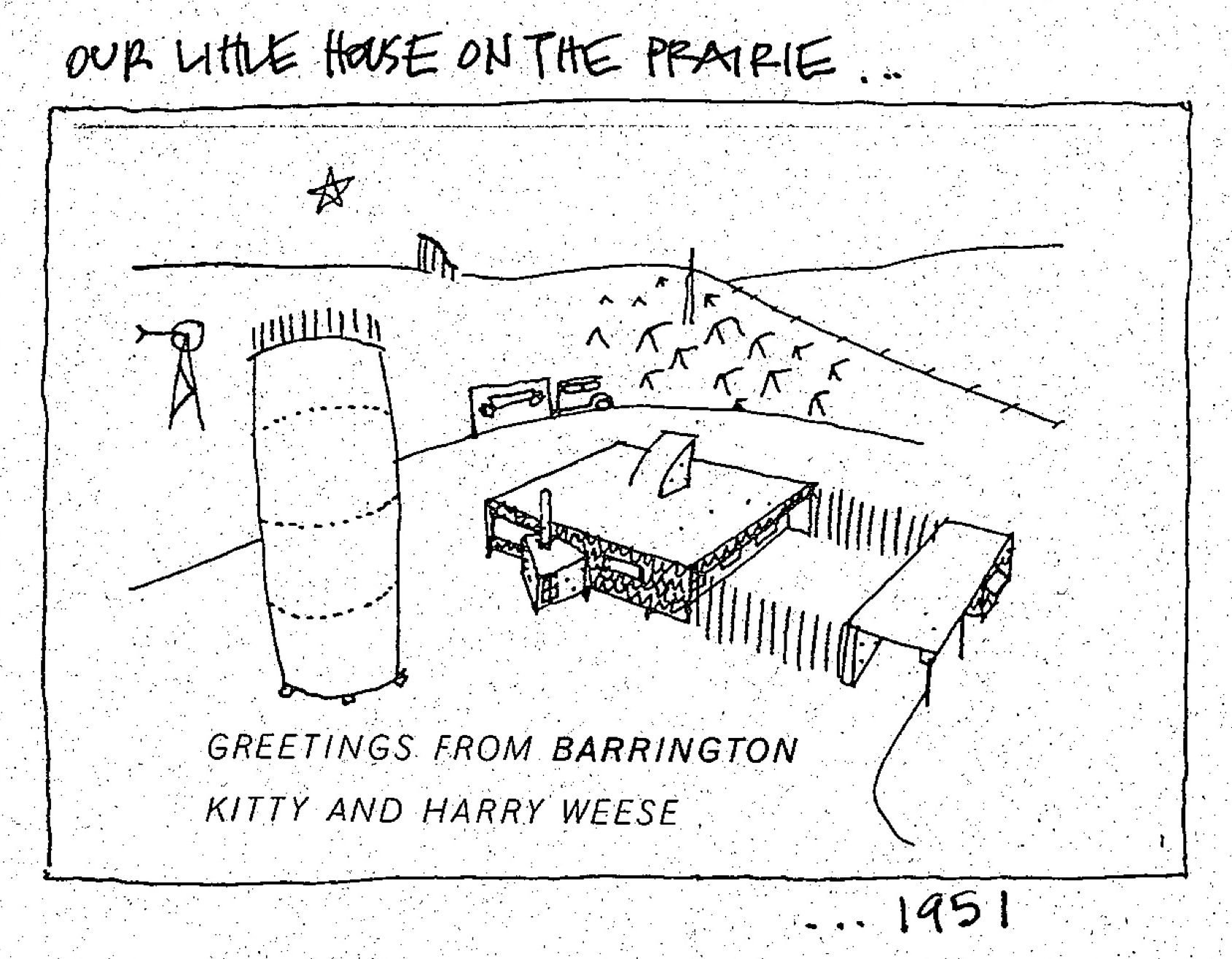

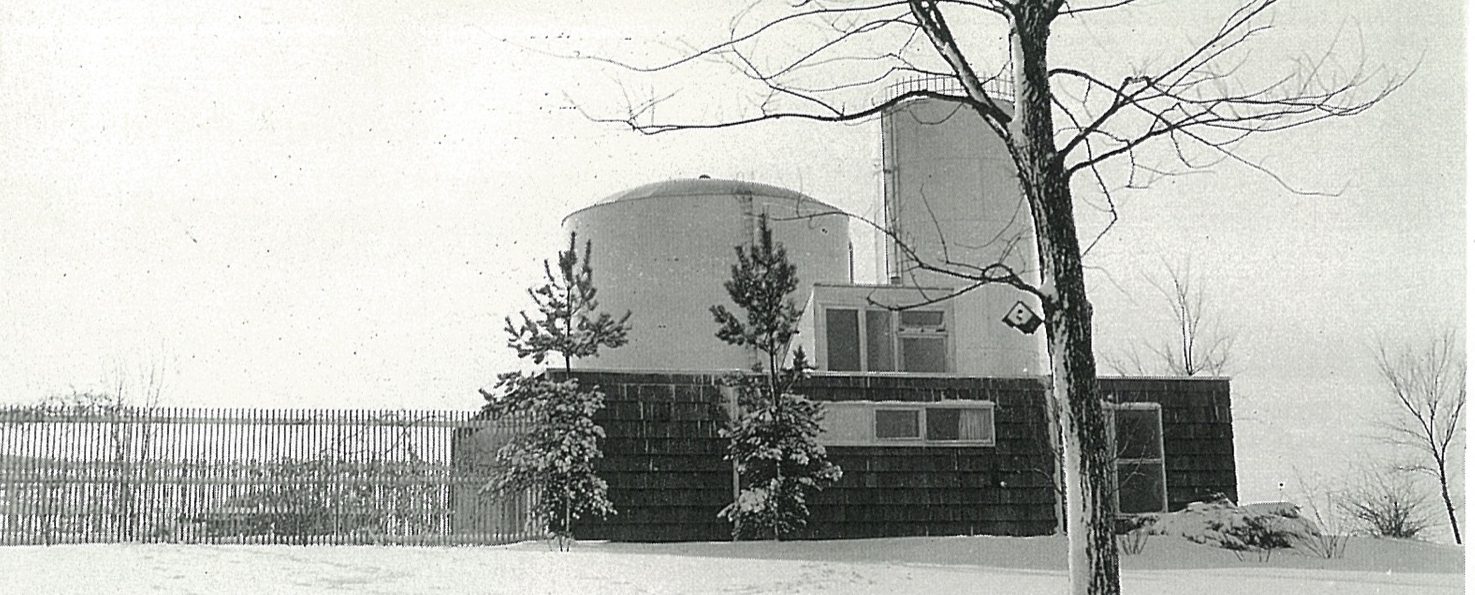

We spent weekends and summers in the country forty miles northeast of Chicago. Now it is wall-to-wall suburbia, but back then, we bundled our five-person family, one cat, two turtles, and several guinea pigs into the car and drove (pre-Kennedy expressway) through many stoplights to the little town of Barrington, Illinois. There, we lived in one of my architect father’s early houses. Built on a lot adjacent to two immense water towers belonging to the town, the house was modern and modest; a one-story house with a flat roof, carport, gravel driveway and a fenced-in garden the three bedrooms emptied into. It was sparsely furnished, and I will always remember the black-and-white linoleum floor. Mom found some dinner-plate-sized checkers pieces and we played checkers on that floor to our endless delight.

Some years later, my grandfather gave my father a nearby five-acre (two-hectare) plot of land, which consisted of a hill, many large oak and hickory trees, poison ivy everywhere, and a hand-dug lake topped off with a pet alligator. Here, my father built a wonderful and quirky house (prebuilding code) he named “The Studio.” We spent many years toggling between city and country. This was a refuge from the city for my parents, and for me, a secret garden of woodland flora and fauna.

Studying with the Eamses & Co.

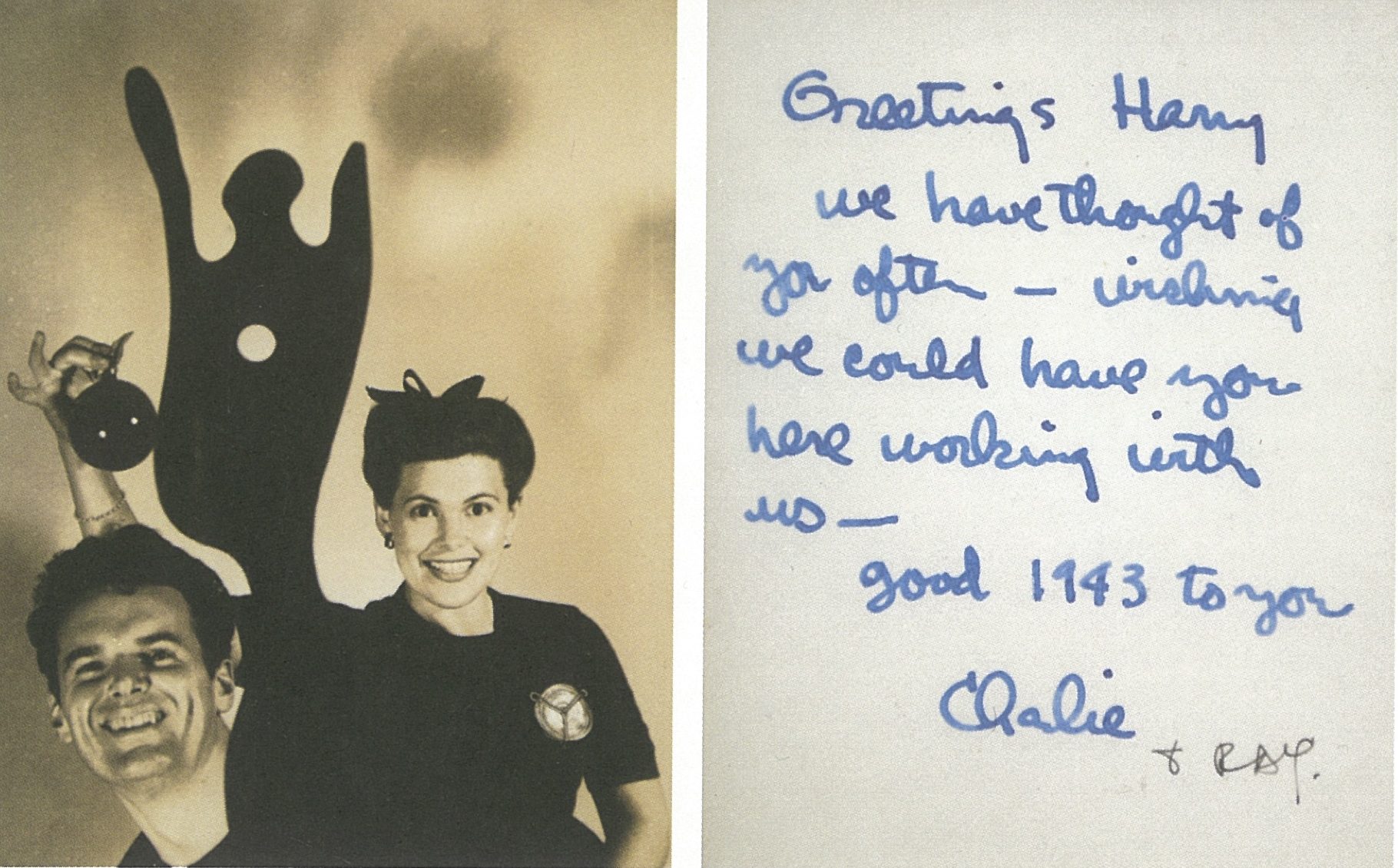

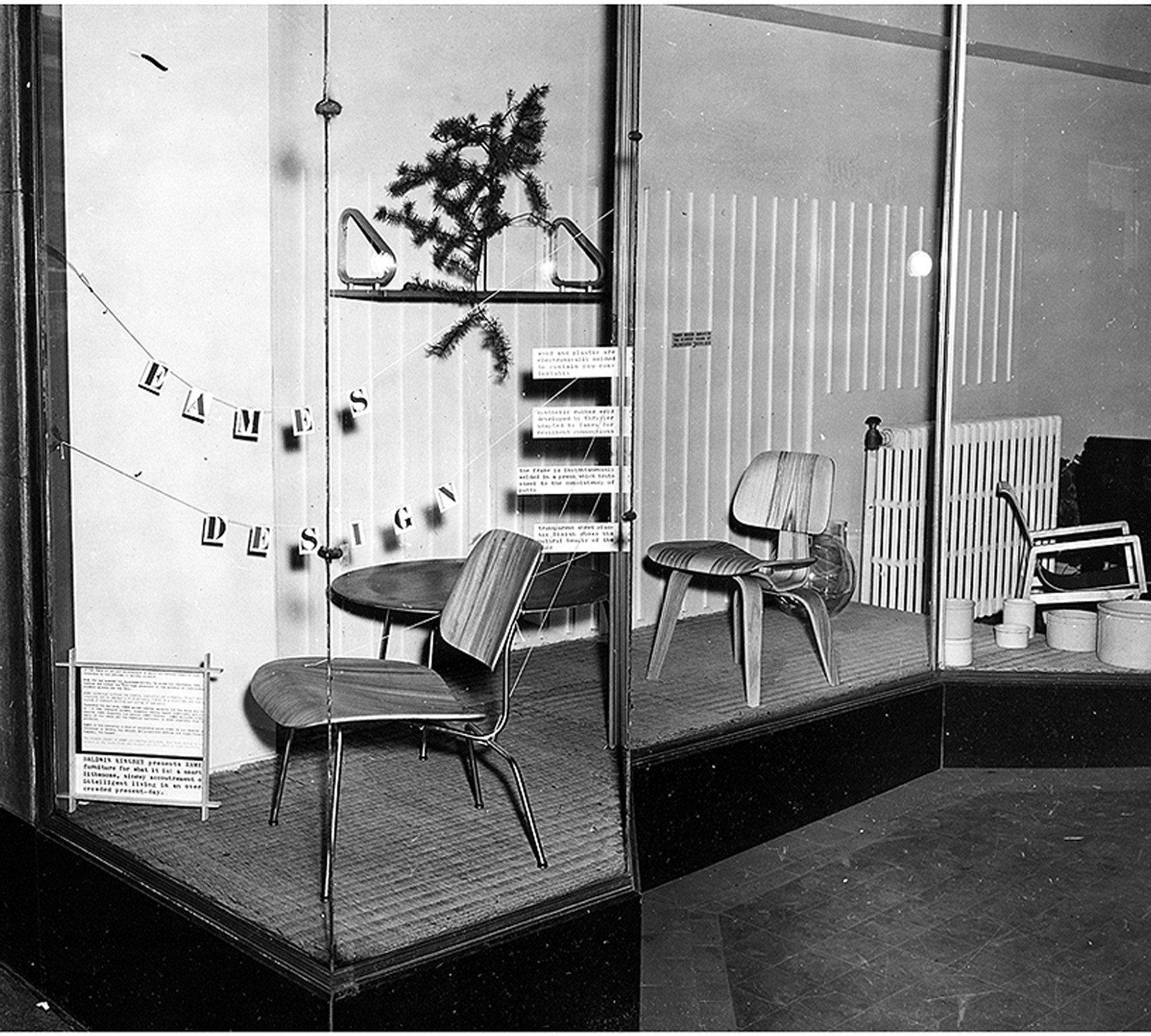

After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in architecture and engineering, Dad studied in Michigan at the Cranbrook Academy of Art with Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ben Baldwin, and a host of others who were living and creating modern design at a time when the atmosphere was ripe for it.

As history has revealed, many became household names, even demigods, in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern. These people were some of my parents’ closest friends.

My father and Ben Baldwin had won a few industrial design awards from the Museum of Modern Art while at Cranbrook, so they decided after graduation to “hang a shingle”—Baldwin Weese—to practice architecture in New York City. They worked together for a year but decided to convivially go their separate ways; Ben stayed in New York, and Dad returned to his birthplace, Chicago. But first, Ben introduced my father to his sister Kitty.

When Harry met Kitty

As my father approached the house to meet Kitty for the first time, she watched him jump over the fence rather than use the gate. That did it for her. He was a nonconformist, an inventor, a man who loved to use the path less traveled. He had no use for convention as it was, in the post WWII era. The overriding spirit was “rebuild,” therefore “build anew.” This was the perfect time for him to launch his architectural career in Chicago. He founded the architecture firm Harry Weese & Associates, which lasted for fifty illustrious years. My mother, who was southern, elegant, and graceful, was over the moon for this artistic, restless spirit. Not a typical match, but it worked; he needed her organized calm and “good eye for design” to manage his ambitions.

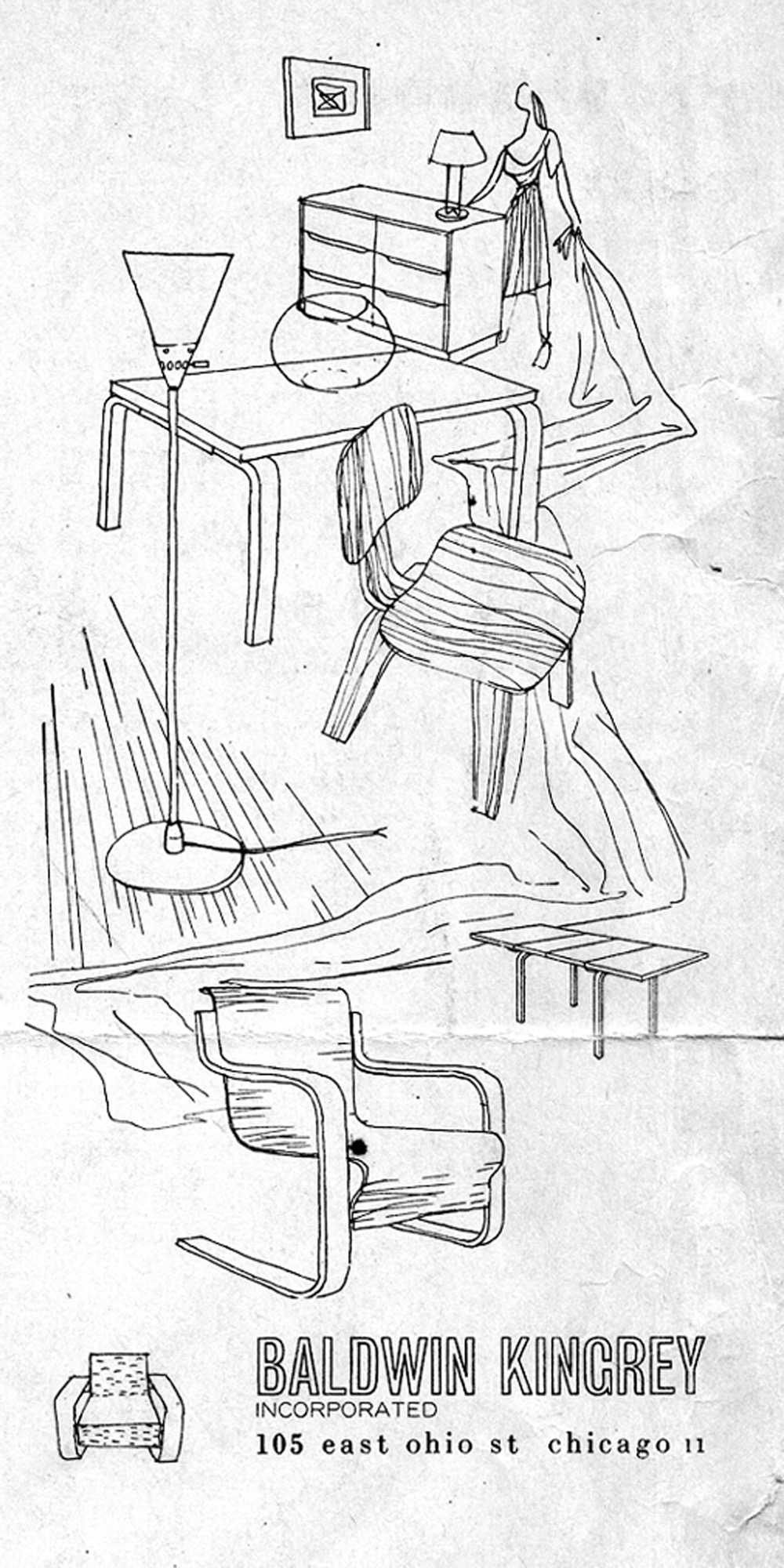

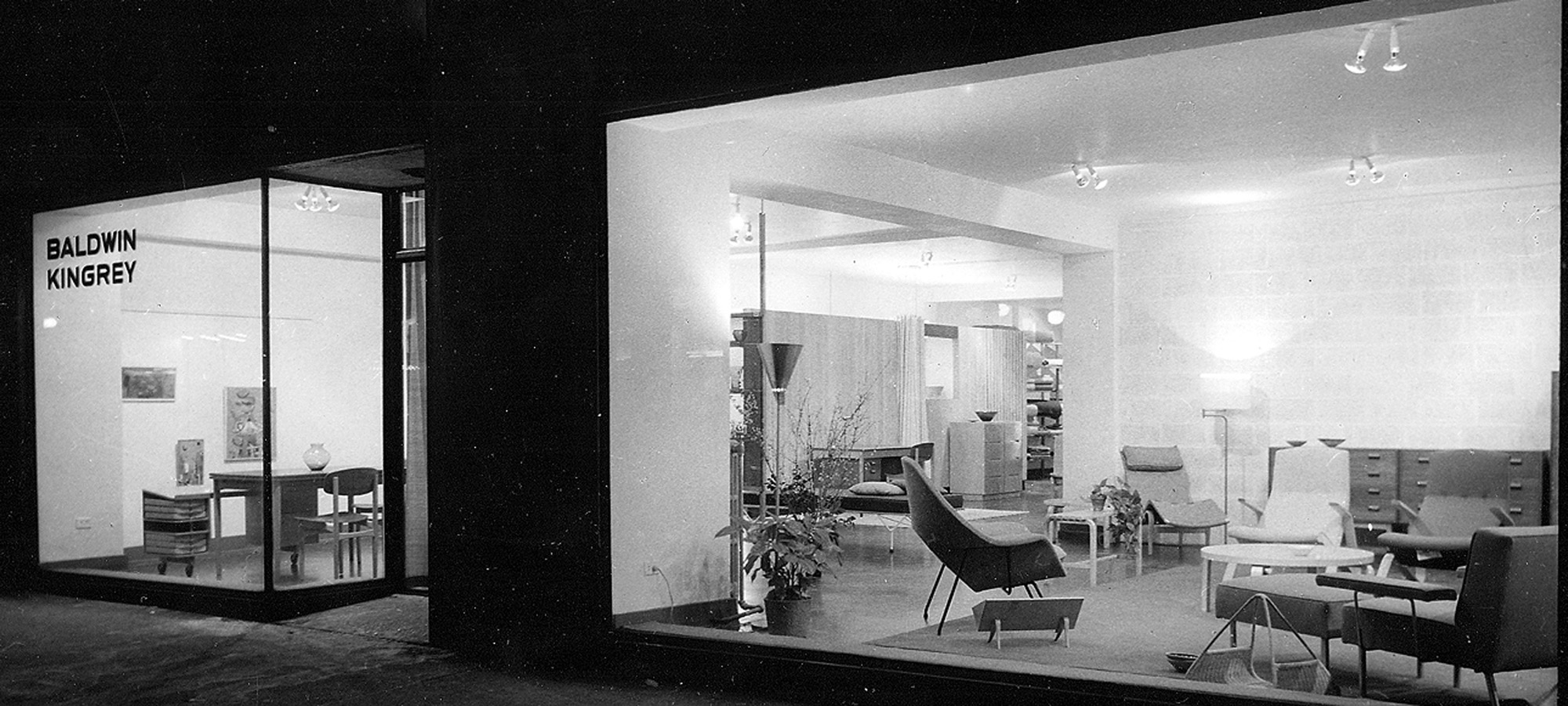

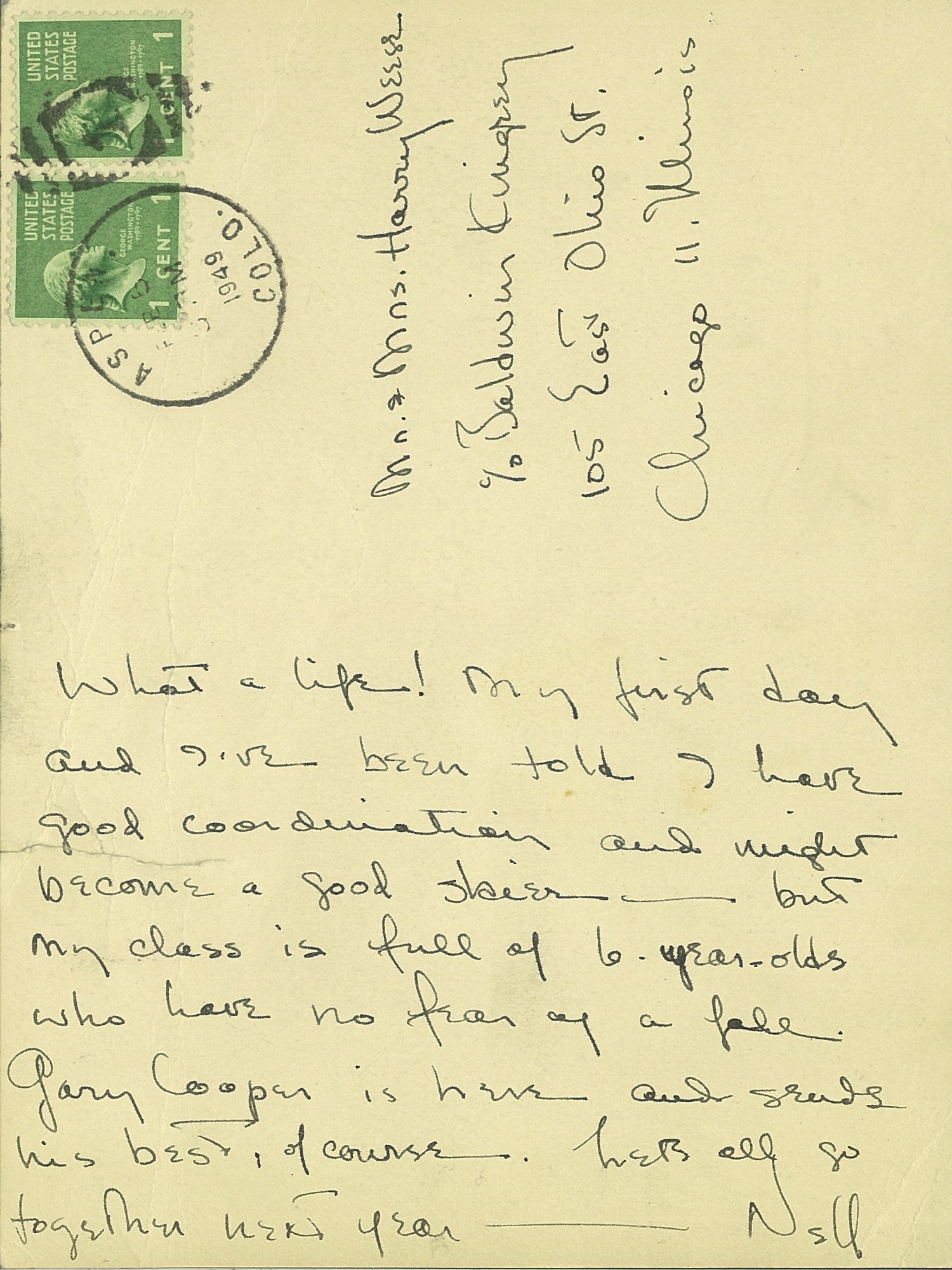

Baldwin Kingrey store in Chicago

In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father. While in the navy for three long years he kept a journal that he scratched in during calmer moments at sea. Here is an excerpt describing his vision for a retail store, entered on May 26, 1943,

“Thought of the (retail furnishings salon) shop for gathering together all beautiful and useful modern objects, which could be termed ‘furnishings’... Anonymous discoveries and subcontracted and assembled pieces of my design: foam and webbed couch in church pew form, telescoping coffee tables of magnesium or plastic, ... fabrics ... grass matting to a special design ... restaurant adjacent, movies, bar, a small haven for those interested ... a trip abroad to buy imports first thing after peace.” “In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father.”

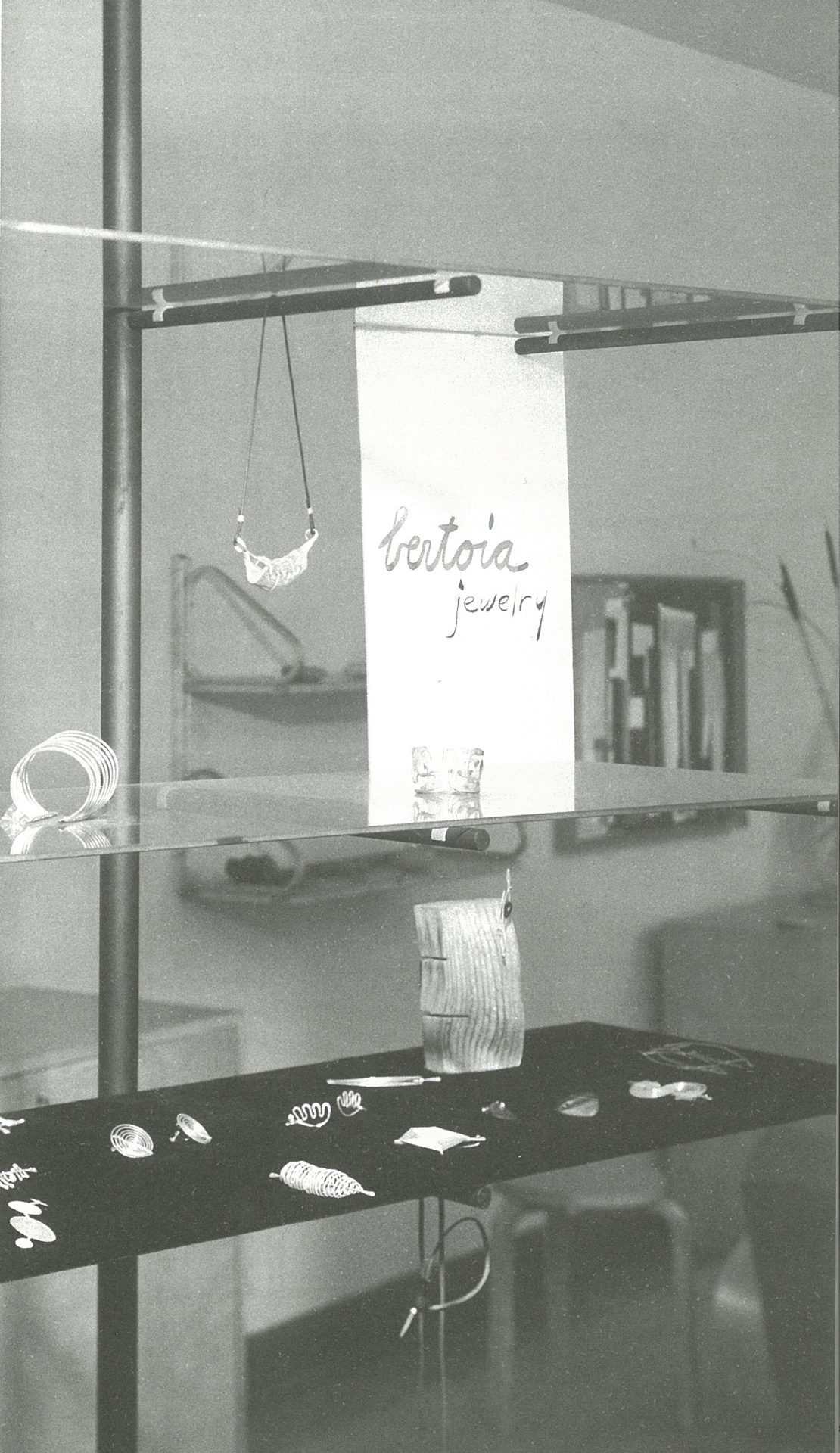

Wasting no time postwar, Dad got permission to handle the Midwestern franchise for Artek furniture from Scandinavia. Ben Baldwin designed fabrics and window displays. Harry Bertoia showed his jewelry, James Prestini sold his turned wooden bowls, artists queued up to exhibit in the space, and Baldwin Kingrey opened its doors to an eager audience hungry for modern design.

In words from John Brunetti, author of Baldwin Kingrey, Midcentury Modern in Chicago, 1947–1957,

“Baldwin Kingrey was more than a retail enterprise. It served as an informal gathering place for students and faculty from Chicago’s influential Institute of Design (ID) as well as the city’s architects and interior designers, who looked for inspiration from the store’s inventory of furniture by leading modernist designers such as Alvar Aalto, Bruno Mathsson, Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen.”

My father started his architectural practice at a drafting table in the back of the Baldwin Kingrey store. He did all the graphics for the store, designed a line of furniture and lighting he called BALDRY, designed open shelving of floating glass and steel poles to display Bertoia jewelry, Venini vases and “Chem Ware”—beakers and Petri dishes in simple, beautiful forms, that they found in the industrial section of the city. There was resourcefulness, an informality, and a frugality at play. In my mother’s words,

“Harry and I stopped at a place that sold Cadillacs on LaSalle Street. They were selling out their leather for automobiles, so we bought the whole batch. A lot of our furniture was covered in Cadillac leather! We were in a sense the precursor to Crate and Barrel. They came down to study us a lot. Carole Segal (founder of Crate and Barrel) was a friend of mine, and I gave her help. I gave her a lot of source material.”

As I was growing up, there was a steady stream of visitors, all immersed in modern design. My mother reminisced,

“You couldn’t travel across the country without changing planes or trains in Chicago. Everyone would stop in Chicago. The people that rushed into Baldwin Kingrey were mostly from the city and they didn’t have much money. Instead, they had some sort of new outlook—a vision. They loved the simplicity of our ‘plain’ furniture.”

The road was unpaved, the waters uncharted, the possibilities endless. Many would visit our house to exchange ideas, talk about projects, drink a cocktail or two, even draw at the dinner table. One of these more salient meetings I remember clearly:

I must have been ten or eleven when a distinguished elderly gentleman came to visit us in Barrington. My father was notably excited to share our modern house with him. When it was time to leave, he escorted him down the walkway under the grape arbor to his car with me trailing behind. As he drove off, my father turned to me with tears streaming and whispered, “There goes my mentor. There goes the most important man in my life.” This was none other than Alvar Aalto, who had been Dad’s professor and was a great influence on his architecture and design philosophy.

First pitstop in Aspen

When peace came in 1945, Dad stepped off his ship in San Francisco and he and Mom drove eastward. On their way back to Chicago, they stopped in Aspen and took some black-and-white photographs of downtown. The town consisted of several stone and brick buildings—the Courthouse, the Wheeler Opera House, the church and Hotel Jerome. All other structures were small Victorians, a few storefronts, dirt roads, and occasional wooden lean-tos that sheltered a few dozing horses. Many of the houses had been plunked on rubble walls to speed construction for miners and their families in the boom of the late 1800s. Builders often used pattern books with a 12/12 pitch for snow load, imparting a human scale that has long since been lost.

Dad—an avid skier—fell in love with Aspen and began a tradition of visiting each winter and summer that lasted throughout his life. Luckily, he included us in this adventure, and, thus, I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as “the town Chicago built.”

“I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as ‘the town Chicago built.’ ”

In the 1940s in Chicago, my parents were friends with Walter Paepcke, a successful industrialist, philanthropist, and president of the Container Corporation of America. It was Walter’s remarkable wife Elizabeth, a notable influence on Chicago’s cultural life and one of Mom’s favorite people, who exposed Walter to modern design and artistic sensibilities. In this spirit, Paepcke consulted with Walter Gropius, brought Laszlo Maholy-Nagy to the Institute of Design, befriended Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer, and photographer Ferenc (Franz) Berko, also at ID at the time. Mom and Dad intersected with ID, as the campus was a hub for young and ambitious modernists.

In a memoir, Elizabeth Paepcke describes her first impression of Aspen after skinning up the mountain in 1939,

“At the top, we halted in frozen admiration. In all that landscape of rock, snow and ice, there was neither print of animal nor track of man. We were alone as though the world had just been created and we its first inhabitants.”

Walter Paepcke first visited Aspen in the spring of 1945 urged by Elizabeth. To him, this seemed the idyllic place to implement a new Chautauqua. The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, “for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.” Thus the Aspen Institute of Humanistic Studies was born. Herbert Bayer was brought in to oversee the design of the campus, and Franz Berko became the Institute’s in-house photographer. The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.

“The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, ‘for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.’ ”

“The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.”

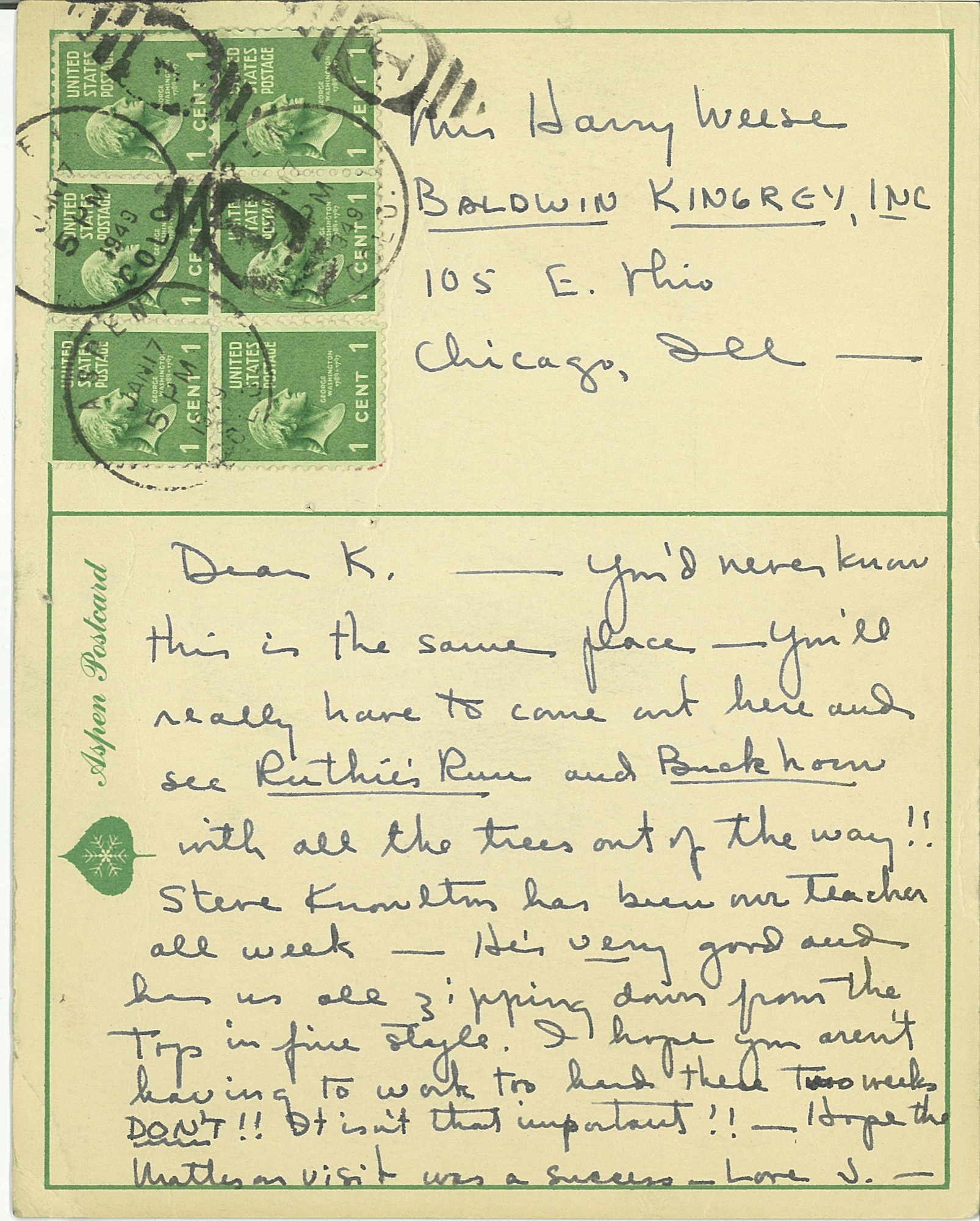

There was a palpable charm to Aspen in the fifties and sixties, which I feel so fortunate to have experienced first hand. Many Europeans returned to the town to settle after serving in the famed 10th Mountain Division during the war. Their training camp, Camp Hale, was nearby and enlisted men would often ski Aspen on the weekends. Friedl Pfeifer was one who started the Aspen Ski School; Fritz Benedict set up an architectural practice. After the war, many of these veterans taught skiing in winter and worked as carpenters in summer. Their wives typically ran the shops, bakeries, and clothing stores in town. Franz Berko stayed, continued his photographic career, and raised his family. His wife Mirte ran a toy shop that sold wooden toys from Europe. Herbert Bayer designed the early buildings at the Aspen Institute and settled in town with his wife Joella. Fritz Benedict, the noted local architect, married Joella’s sister Fabi, and he began developing Aspen. Joella and Fabi shared a famous mother—the poet Mina Loy. This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its “quiet years.” My parents were in the midst of the action.

“This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its ‘quiet years.’ ”

Christmases at the Hotel Jerome

Nora Berko, daughter of Franz and Mirte, remembers visiting us at the Hotel Jerome every Christmas. We always stayed in the southeast corner with full view through the Victorian lace curtains of Main Street and Ajax Mountain. As our collective parents went out to dinner and dancing, usually at the Red Onion, we had full run of the rickety hotel, much like Eloise at the Plaza. With its worn and dusty velvet furniture, Victorian floral wallpaper, and black-and-white photos of skiers sporting the reverse shoulder stance and the latest style of stretch pants, it was a far cry from our modern and minimal environment at home. We ran up and down the creaking stairs and played in the elevator—a novelty—as it was the only one in town. The rooms cost ten dollars per night, radiators clanked, and in some seasons ropes were ceremoniously draped across the room sinks warning of giardia in the water. But we loved the Jerome. It felt like an old comfortable shoe. The Paepckes leased the hotel as well as the Opera House so Elizabeth had license to paint the exterior white with light blue arches over the windows. The hotel looked like a grand Bavarian wedding cake in a perpetual wink; an impressive structure always easy to spot for a youngster finding her way home after ski school. It stayed this way for several decades.

Every Christmas we walked through snowy streets to the Berko’s for Christmas dinner. Their house was a modestly scaled and cozy Victorian in Aspen’s west end. Real candles burned on the Christmas tree, which was festooned with wooden ornaments from Mirte’s toy shop. Marzipan treats imported from Europe were served. There was no central heat. Brrrr. But for a young girl, I was sure that I was encompassed within a magical snow globe.

Aspen became our second home

In the late sixties, my mother bought a small Victorian in Aspen's west end for a mere pittance. We began to spend summers in the mountains, which was a blessed relief from the mugginess of the Midwest. My father worked on projects in and around Aspen. Many went unbuilt but some were realized, including the Given Institute. He had a plan for a new airport, and he wanted to bring light rail from Glenwood to Aspen to alleviate vehicular traffic. Always drawing, usually at the kitchen table, I rarely saw him without a pencil in hand. In 1969 Charles Moore (who taught at Yale), and Fritz Benedict lured a class of Yale architectural grad students to spend a summer in the nearby mountains and build experimental projects. When these young, handsome students appeared, they were eager to rub shoulders with my father at his kitchen table. (A few rubbed shoulders with his daughters as well!) One of these architects, Harry Teague, arrived and never left. Over four decades, he has made a significant imprint on the town, designing notable residences and many of Aspen’s most prestigious cultural buildings, including Harris Hall, the Aspen Music School campus, and the Aspen Center For Physics. He has become one of Aspen’s “own” by championing a humanist aesthetic that continues to raise the bar of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley.

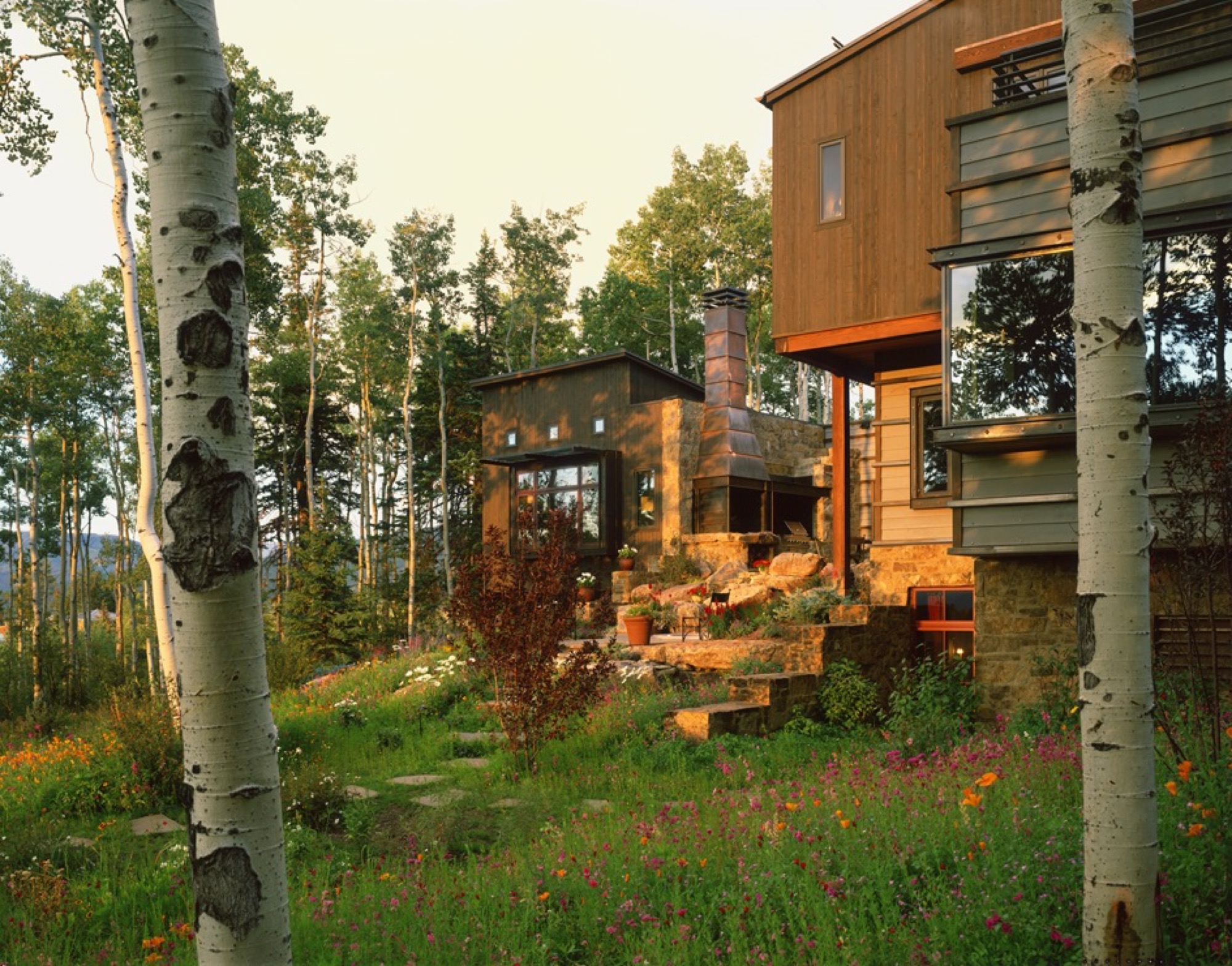

Aspen today

Though old Aspen is rapidly fading, thank goodness there are offspring. I am currently collaborating with Teague on a family compound for Nora Berko and her family that incorporates her father’s studio, now designated historic. Her daughter Mirte has dedicated much time and effort organizing her grandfather’s impressive archives of photographs for us to appreciate into perpetuity. The Aspen Institute carries on robustly while continuing to pay homage to its early founders and players. △

Read "Growing Up Weese" to find out what artist and designer Marcia Weese is up to today.

The Architect Explorer

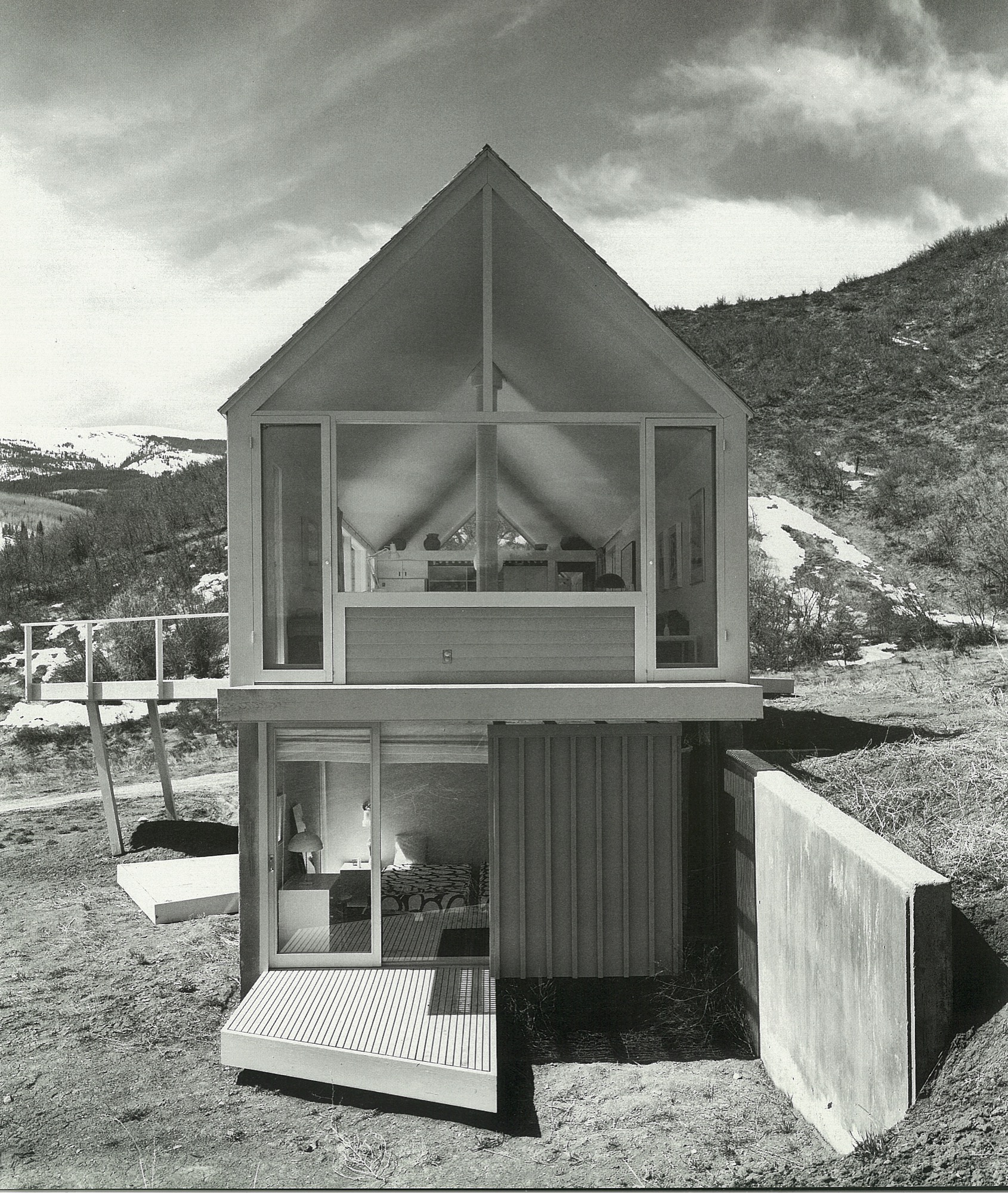

Colorado architect Larry Yaw interviewed by his journalist daughter

Colorado architect Larry Yaw, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, has nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond. An intimate conversation with his journalist daughter...

Sitting on a mossy rock in a tall stand of aspens next to my dad, a couple of hours into trying to find our way from Willow Lake back to the Maroon Bells parking lot, I started gnawing on my mom’s teriyaki beef jerky from my backpack. We had left the trail long ago, and I was convinced we were lost. I must have been about eight years old at the time.

“We’re not lost, we’re exploring,” is probably how my dad, architect Larry Yaw, responded—a claim that would echo through my young years as I followed him through the backcountry of the Elk Mountains in Colorado, across Kashmir in India, and through The Wind Rivers, The French Alps, New Zealand, and beyond, along with my mom and three siblings.

We got lost a lot, sort of on purpose, in the mountains. Yet never once did I see my dad flinch in these moments. Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul. I’d watch as he’d get this shrewd sparkle of excitement in his voice as he strategized on which ridge to follow, or which drainage would lead us back to the tent, all the while managing his family on the verge of the fearful discovery that our dad, really, had no idea where we were. Yet, now, as I bring my own young family into the woods to play and discover, I realize that my dad’s resourceful and poetic confidence that has intrigued me over the years has penetrated my own psyche deeply, and I strive to encourage that sensibility to seep into my kids’ sense of adventure. And, just as he did for our family, my dad has left an indelible impression on the contemporary design ethos of the Roaring Fork Valley, as well as countless alpine communities across the Mountain West.

“Getting lost in the woods, in the place he calls his chapel, was merely another form of sublime and creative adventurism for him—much like his career as an architect and artist—and it fed his cowboy-style soul.”

Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond, with an exceptional roster of clients and creative business partners as his co-conspirators; and he propelled them towards the outer edges of what’s possible. If I were to guess, his clients might sum up his character with a story similar to mine, yet the chapel would be his drafting table, and the map would be the radical ideas he has hand-sketched on camel-colored paper for the artfully crafted architecture he has envisioned. Sure, during his forty-six years creating innovative designs in the mountains, his aesthetic has shifted and grown, but his passion for the rawness of the backcountry, and for the purity of connecting people to place and to nature has remained firmly in tact.

“Since 1970, his iconic passion has manifested in his projects as he nudged modernism forward in Aspen and beyond.”

As his youngest daughter, I knew all of this, sort of, but it wasn’t until we had this conversation that I truly understood the gravity of how particular vignettes throughout his life have justified, and even come to imprint themselves, on his design, his spirituality, and his personal approach of getting lost—before finding a path.

Herein lies our recent sit-down at the kitchen table, an intimate chat between an architect and his daughter:

LYR How has living in the mountains influenced your design?

LY I’m the guy who can’t stop myself from climbing up and looking to see what’s on the other side of the ridge, or from going up to the end of a valley to see what’s there. If there’s some association with exploring, and innovating beyond the expected, I’m in. Therefore, my lifestyle has been defined by, and inspired by, active outdoor living, and attached to that is the adventure of it. Adventure is a part of everything I love to do—physical, intellectual, and spiritual adventure. And, therefore, I’ve begun to regard the artform of architecture as a basecamp for this; a basecamp that is sustainable, economic in scale, but very much connected to nature as that is so much a part of the adventure of being alive and in the now, wherever here is.

“Adventure is a part of everything I love to do ... I’ve begun to regard architecture, or habitation anyway, as a basecamp for this.”

LYR Who influenced you as an architect?

LY First, the biggest influencers have been great clients of a contemporary persuasion, who relish the process of exploration and testing. There are other architects also, such as Romaldo Giurgola (“Aldo”), The Dean of Columbia School of Architecture, where I completed my Master’s studies. He would sit down and talk in these simplistic terms about the choreography that you create architecture through; the path you take and how that enriches you, and enriches the purposes of design. Louis Kahn—his work and writings inspired me.

And, the firm Morphosis Architects creates fabulous, courageous, contemporary, sculptural, and adventuresome architecture. As you traverse their spaces, you’re taken through them with this marvelous, layered, spatial experience that therefore inspires the choreography of getting from here to there.

LYR What’s your experience of being a modern architect in the Roaring Fork Valley, where opulent traditional mountain architecture is so dominant?

LY There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things. Even though I’ve been involved with opulence, I design around the expectation that you don’t let the house own you. And, now, there is a cultural shift toward an awareness that we have to be stewards of the land, and be mindful of not writing out a big order for the resources. That shift has brought clients who want thoughtfully crafted, understated, simple in form, and more directly responsive design.

"There’s opulence of thought and opulence of material—and those are two different things."

Also, a townscape is really a library of cultural expressions over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time. Hopefully, what I do is an expression of my times and this culture, and doesn’t grab a crutch out of architecture’s past. Because the work of my firm significantly influenced the evolving character of architecture in the New West, I was elevated to the prestigious College of Fellows (FAIA) by the American Institute of Architecture. Our working mantra of design is that of “place-making” where architecture and nature are seamlessly integrated to the betterment of both.

“A townscape is really a library of culture preferences over time. Given that historic perspective, a log cabin is part of the miner’s time.”

LYR You were raised in rural Montana. What did that upbringing impart to you?

LY Growing up in Montana, I really experienced these rural ranch and farm compounds that were formed over generations. They were always designed by the simplest means, in simple forms, and they seemed to sit respectfully on the earth. When I started studying these things, I discovered that they were really forms that described contemporary architecture in their simplicity. They were formed in protective surrounds, and were organized around working proximities, yet there was always a place for enrichment, like a little garden near the front porch. Then, these compounds grew organically—out of inelegant purpose, and rural rationality. I didn’t appreciate it then, but as I studied architecture, I started pulling out of my experiential self, and those things all matched up—that is contemporary architecture. It did not tread heavily on the land; it embodied economy of means; it had simple forms and echoed its context—all things that are generationally taught or experientially taught. They solved problems there, out of their own devices and their own means.

LYR How has design carried into, and impacted, other areas of your life?

LY It has opened my eyes. When I travel, I see different things; I wonder about them; I take them in. And, what I’ve learned is that I like evocative things. Evocative means you hate it or you love it but it nevertheless stirs emotion in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind. And, that’s true in architecture. The creative process and everything associated with it; the people you work with and the collaborations—they fuel my worthwhileness and my sense of adventure.

“I like evocative things…. You hate it or you love it but it stirs something in you, and takes the lethargy out of your mind.”

LYR Tell me about the Blackfeet Indians, a tribe you became close to when you were young, and their impact on you, your design, and your art.

LY When I was twelve years old, I went to Browning, Montana, in the middle of the Blackfeet reservation, and there sat this gorgeous little Indian girl. She was about my age, dressed in a traditional beaded, white doeskin dress, and I was enchanted. Her name was Virginia Home Gun. That enchantment turned into a friendship with her. It turns out that her father was the chief of the Blackfeet Tribal Council. Over time, through traditional ancient ceremony, they made me an honorary member. That really stirred me. It continued beyond that, and I started reading and studying about the rituals and legends that were the spiritual glue of their life. The Blackfeet regarded themselves as a creature of the earth, and they understood the balance of their needs with earth phenomena. They would give thanks to the buffalo, and honor a slain enemy for valor. For me, it went from the idealistic warrior image when I was young, to understanding their spiritual nourishment that kept them who they are. That translated to me later on into a series of paintings that I call “Once Proud.” That’s my way at this point in life of telling the story of westward movement and how it maimed the spirit and freedoms of our native inhabitants of this place. This made us feel sort of culturally guilty and I was inspired to tell that story.

LYR What is the status of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley, and what role did you play in getting modern design where it is today?

LY Aspen has always been a place that embraced aesthetic adventurism, or tolerated it anyway, and has always fostered intellectual and artistic courage. My firm, my partners, a highly talented thirty-some staff, and our clients have allowed us to be one of the forerunners of the movement here. Personally, I haven’t pushed modernism [in the valley] for recognition; we have had clients and circumstances that permitted that kind of solution and character. But within my firm, I’m known for pushing beyond the expected, and going to a higher level of art form and different level of expression; questioning, pushing, improvising, and going beyond even what clients want. Straight competency in architecture is a mid-level solution—I advocate for artfully courageous and innovative solutions that are bigger than the problem.

LYR Who are the people who want modern architecture in the mountains? What makes them different from the “typical” client who wants that enormous heavy log mansion that says, “I have a lot of money, and I live in Aspen?”

LY Some people are here because it is a new bar on their reputation epaulette. The people who I gravitate towards, or who gravitate towards our firm, are here for reasons I’ve sorted out—for the adventure, the backcountry, and things that support our minds, bodies, and spirits. These are all truly good characterizations of our lives, and our personal culture. To put it into context, I’m not going to design three little sitting areas around the master bedroom so you can sit inside all day. You get out of bed, you have breakfast, and you go ski; you get out there.

In that, a question I always ask is: Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context? The answer is both depending on where you are, but it's a question I ask of it because its one of the beginning points that I use to align my sensibilities with those of a client or a place.

“Is architecture derived of context, or does architecture create context?”

LYR You get lost on purpose, in a way, right? How has this personal quality informed your design sensibility?

LY Freud said that problems couldn’t be solved by a consciousness that created them. In other words, you cannot solve problems where there are too many givens; otherwise you just spin inside the givens. Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost, I just feel like I entered another chapel as it engages another form of creativity, curiosity, and adventure in me. Being lost is inspiring too—when I was really young, out hiking and going to crazy places I’d never been, I marveled at earth forms, the magic to them, what got them there. As I went on, I studied geomorphology, and it all boiled down to tectonics of eruption, erosion, accumulation, weather, and all of nature’s will upon those things. It’s really compelling, and asks compelling questions, and I found some answers that I’ve portrayed in my painting.

“Part of the creative process is being lost, disoriented; you are seeking an answer in a way. Therefore, I never feel lost.”

Nature can also help you appreciate your existence, be a stimulus for enlightenment, and fuel lifelong curiosities. As architects, we must embrace that kind of creativity and spirituality, the kind that enhances who we are, so as to create well being.

And, Lindsay, I can find my way back from anywhere.

A founding partner of Cottle Carr Yaw Architects, Larry Yaw has designed many of the firm’s award-winning projects—from resort and community design to corporate buildings and private mountain homes. In 1993, Yaw was named to the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows, the highest award given to the profession’s most respected architects. His projects are regularly published in architectural books and national design magazines.

Yaw received his Master’s Degrees in both Architecture and Urban Design from Columbia University and has since been a lecturer and design critic at several western universities. Believing in the importance of civic involvement, Yaw is also a founding board member of the Aspen Art Museum.