Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Scandinavia Trip Itinerary

When fall comes each year we find ourselves cleaning house, organizing, downsizing, and taking stock of the beautiful sunny memories of summer. As the kids nap peacefully this afternoon, we're snuggled on the couch watching the last of the orange and yellow leaves of cottonwoods drift quietly in the backyard. We're taking this window of opportunity to send a special inspirations email today about our summer vacation to Scandinavia. Along with our two kids, we explored Denmark, Sweden, and Norway for three full weeks in July. There are plenty of luxury-focused travel guides like Monocle, CITYX, and the Michelin Nordic Guide that are excellent resources, but we wanted to share with you some of our favorite places from the trip. Many of these links will go to our website where we have included pictures and more details about our experiences:

Denmark

When we began our trip we planned a few days of doing nothing so that we could adjust to the time zone and enter vacation-mode. We rented an Airbnb home in Hellerup (just North of Copenhagen). The home is located in a quiet neighborhood which was a perfect setting to help us get settled. Bonus, the house had a trampoline. We cooked meals, explored the town, and let the kids run loose at the most amazing children's museum, the Experimentarium.

Arne Jacobsen's iconic Station Wall Clock seemed to be everywhere we went in Denmark, including hanging in the Airbnb house. We purchased one for our home in Boulder to remind us of our trip and the importance of timeless design.

You must go to the Louisiana Art Museum. The art is very good but the architecture of the building is what really stands out.

When in Copenhagen, eat lunch at Copenhagen Street Food, specifically try Tacos Chucho. Get afternoon coffee and cake at 108 Restaurant and also go there for dinner. Stay at the D'Angleterre hotel and make sure to experience the spa and pool. You'll certainly see Tivoli Gardens and when you do, eat at Gemyse and try to get a seat inside the greenhouse. Great coffee at the four locations of Coffee Collective.

Sweden

When in Stockholm, have lunch at Oaxen Slip. Go to the Vasa Museum. Stay at the Grand Hotel and eat at chef Mathia Dahlgren's Rutabaga. Take a day boat to Vaxholmarchipelago and have lunch. Visit the old town of Stockholm, Gamla Stan, and make sure to buy candy at Polkagris Kokeri. Eat pizza dinner at Tutto Bello. For a quick lunch go to Kalf & Hansen and then get a coffee at nearby Drop Coffee.

In the unassuming town of Växjö, Sweden there is a beautiful hotel and restaurant, PM & Vänner. If you're traveling with children, you'll also want to spend an afternoon at the local park and playground, Linnéparken.

We had the opportunity to meet with the renowned designer, Pia Wallen, in her magnificent Stockholm design studio/home. Pia is the designer of the iconic, Cross Blanket, which we sell at our Shop in Boulder and that is part of the Swedish design museum. We wrote a more in-depth piece about Pia, here.

We discovered a Swedish architect worth noting, Jonas Lindvall, while staying at the PM & Vänner hotel, which he designed. His body of work is incredibly beautiful, modern, and considered. We especially like his furniture collections such as the Miss Holly Chair and Table.

Norway

We stayed at a nice and centrally located Airbnb in Oslo, Norway.

When in Oslo visit the Oslo Opera House to experience the architectural marvel that it is. This might seem odd, but there is a very good Chinese restaurant in Oslo that's worth eating, it's called Dinner. Go to the Vigeland sculpture park. Best coffee we had on our entire trip was at Tim Wendelboe. Eat at Smalhans.

If you make your way to Norway you'll undoubtedly explore the fjords. We stayed in a picturesque modern cottage in Aurland called 2|92 Aurland. Yes, that is a real a waterfall in the background...it was one of a dozen that surrounds you in the Aurland valley. Absolutely magnificent. Get to Aurland by train from Oslo to Flåm then take the breathtaking one-hour, Flåm Railway to the start of the fjord. From Aurland, take the five-hour Norled boat ride through the fjords to the ocean and end up in Bergen.

When in Bergen we couldn't find anywhere remarkable to stay but so long as you're near the town center, you'll be fine. Eat at Lyscerket and also at Bare Vestland.

Scandinavia is a remarkable part of the world. The people are kind, beautiful, progressive, and reserved. These values inspire us in our endeavors with Alpine Modern and in raising our family. It was a transformative trip for us and we hope that you get the opportunity to travel to that magical North. And if you do, please share with us your experiences.

The Vindheim Cabin: Snowbound in Norway

The Vindheim cabin in Lillehammer, Norway, is inspired by the classic motif of snowbound cabins, with only the roof protruding through the snow.

Architect Håkon Matre Aasarød, partner at Oslo-based studio Vardehaugen Architects, led the design of Cabin Vindheim, situated deep in the forest in the alpine landscape near Lillehammer, Norway. The cabin’s concept was simple: To create a cabin that is small and sparse yet spatially rich. The 55-quare-meter (592-square-foot) cabin, commissioned by a private client and completed in 2016, comprises a large living room, bedroom, ski room, and small annex with a utility room. It functions off the water and electricity grids.

Håkon, who earned his master of architecture degree from the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, where he is also teaching today, has been telling us about this project from its very beginning, keeping us abreast of the building progress in emails and photos. What’s more, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation followed the design and construction of the cabin and documented it in a one-hour episode of the program “Grand Designs”. Thus, we are excited to finally show you the result and introduce you to its lead designer, who lives in Oslo, with his wife, Sigrid, and with his two boys, Syver and August.

A conversation with architect Håkon Matre Aasarød

AM When and how did you know you wanted to become an architect?

HMA I’ve always been passionate about drawing. I can easily recall the wonderful and almost hypnotic feeling I had while drawing Star Wars space ships for hours in my childhood. As soon as I got older and realized that drawing houses and objects was a real job, and not just a hobby, I knew I wanted to be an architect. Today, from time to time, I can still get that wonderful, almost meditative feeling while drawing.

“As soon as I got older and realized that drawing houses and objects was a real job, and not just a hobby, I knew I wanted to be an architect.”

AM What professional path led you to where you are today?

HMA Immediately after finishing architecture school, I started my first office, Fantastic Norway, together with my good friend Erlend Blakstad Haffner. Our studio was a red caravan. We drove from town to town for more than three years, giving architectural aid and inviting the locals to participate in creating new strategies and projects for their hometowns. We had a wonderful adventure and got a lot of attention and won many prices for our method of working. But life on the road was also a bit tiring, so in the end, we had to park our ambulant architectural office.

Then we were invited to make a TV series about architecture for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) and worked as television hosts for a couple of years.

After spending so much time on the participation processes and communication, I felt the need to focus on the building part of our profession and, as a response to this, started Vardehaugen Architects.

AM What’s your design style?

HMA When starting a new project, I try hard not to have preconceived ideas about the style or looks of it. I try to focus on the client’s need and on creating interesting spaces and let the style evolve through this.

AM Where do you draw inspiration for your designs?

HMA Our greatest source of inspiration is our clients and the sites we work on. Every client is different; every place is in some way peculiar and unique. We aim to embrace this in all of our projects.

AM What does “home” mean to you?

HMA Home is the feeling of belonging somewhere. The feeling could be connected to a house, a specific landscape, a mountain, or even a group of people. Places where your story lives.

AM What makes you a mountain man?

HMA Growing up in Norway it’s hard not to have a close relationship to the mountains. Throughout my childhood, we spent a lot of our holidays hiking or skiing. Every Easter, my family still goes hiking in the mountains, and every autumn, we collect sheep for my parents-in-law in the mountains of Norway’s West Coast.

AM When are you the happiest?

HMA Nothing beats spending a day with my two kids at our small summerhouse on the West Coast of Norway.

AM What’s on your drawing board right now?

HMA We work with a fairly wide range of projects. In addition to some cabins and villas, we are currently designing a small chapel next to Norway’s second largest glacier, the Black Glacier, a coastal museum on the island of Frøya, and an observation deck at Norway’s most spectacular waterfall, the 280-meter-tall (ca. 920 ft.) Vettisfossen.

The Project: Cabin Vindheim

AM Who are the clients?

HMA A couple in their mid 50s, both of them passionately interested in architecture and design—in addition to skiing and hiking in the mountains.

AM Describe the design in your own words...

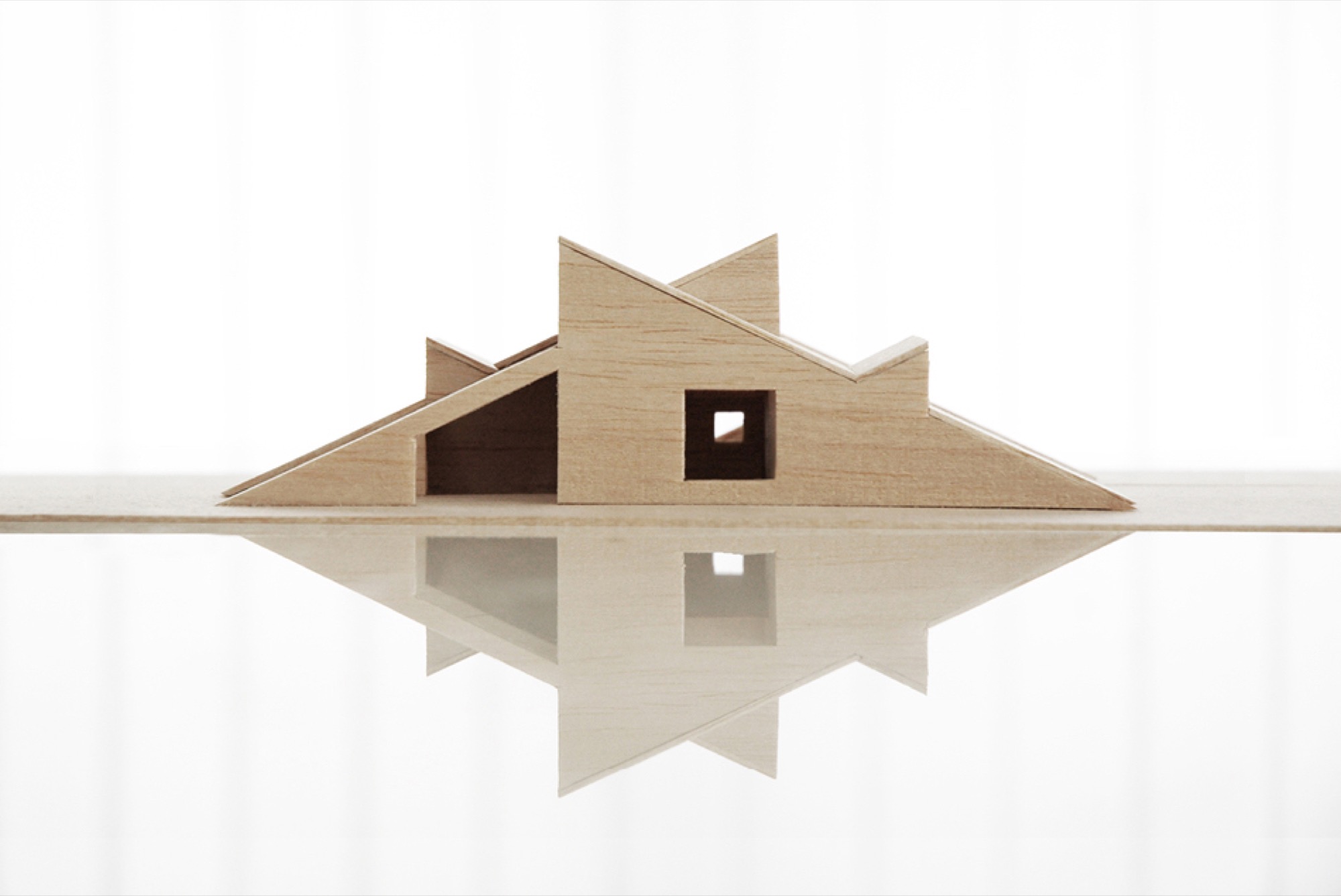

HMA The cabin is a basically a gabled roof where the edges of the roof stretch all the way down to the ground. The ceiling runs uninterrupted through the cabin and connects the different rooms. A series of uplifts creates a rich variety of spatial qualities underneath it.

AM What was the client’s premise at the beginning of the project?

HMA They wanted a small cabin that was sparse and compact but at the same time spatially rich and generous.

AM How did you translate the client’s vision into this design?

HMA With the ambition of creating a compact cabin that at the same time had exceptional spatial qualities, we focused a lot on the physical sensation of scale and space. When is a space too tight? When is it too big? We did this by creating real-scale mock-ups of our design solutions in our backyard to ensure a greater understanding of size and proportions in our project. This enabled us to simply take a stroll through our project and get a sense of dimensions and spatial sequences–even before the cabin was built.

AM What was your inspiration for this particular design?

HMA The external shape of the cabin is inspired by the classic motif of snowbound cabins that have only the roof protruding through the snow. When snow covers the structure, the contrast between architecture and nature becomes blurred.

AM What makes this cabin truly special?

HMA During winter, the roof becomes a man-made slope for ski jumping, toboggan runs, and other snow-based activities.

AM Take us there...

HMA The site is deep in the forest in the alpine landscape close to Lillehammer in Norway. The cabin sits between some tall spruce trees, with a nice view toward a lake. During winter, it’s extremely cold there and hard to get to by car, so you have to cross-country ski for a few kilometers to get there.

AM How did the setting and the site influence your design?

HMA The frosty forests in the region are both beautiful and mysterious, and they’re closely connected to traditional folklore and stories about trolls and other strange creatures. When snow covers the trees and stones, they morph into something new. They become characters, sometimes trolls, sometimes just a beautiful and unique sculpture. I find this notion truly inspirational.

“When snow covers the trees and stones, they morph into something new. They become characters, sometimes trolls, sometimes just a beautiful and unique sculpture.”

AM What are the main materials you used, and why?

HMA The classic Norwegian mountain lodges are covered in dark wood, making them seem both solid and grounded. Inspired by this, the cabin is clad in black-stained ore pine. The interior is lighter, fully covered in waxed poplar veneer.

AM Take us inside...

HMA The sloping roof connects the different spaces, making the entire cabin feel more like one large room.

From the main bedroom and the mezzanine, you can even gaze up at the stars and enjoy the northern light, while lying in bed. When resting in the cabin's bedroom, a large 4-m-long (ca. 13 feet) window creates the impression of sleeping above the treetops and underneath the stars. The main living room is also small but has a ceiling height of 4.7 (ca. 15.4 feet) meters under the roof.

AM What was your biggest challenge with this project, and how did you overcome it?

HMA The site is very far off the grid, and simply getting the materials to the site was quite a challenge. But we managed by always planning with close consideration of the local weather forecast.

AM What is your favorite thing about the cabin, now that it is finished?

HMA Lying in bed watching the northern lights above the snowy spruce trees is a really nice experience.

AM What do the clients tell you, now that they have been living in your architecture for a while?

HMA They enjoy the cabin and spend time there every weekend. The only issue is that they’ve had problems with sheep climbing up the roof. However, I’m sure the sheep enjoy it.

AM Final impressions of the cabin?

HMA We designed a couple of birdhouses for the birds living next to the cabin. Local sparrows and starlings enter the nesting box from a small opening underneath the flexible top hatch. △

Monochromatic Reminiscion

Belgian travel and wildlife photographer Martin Dellicour comes eye to eye with the history of Earth embodied in a herd of muskoxen on the high plateaus of Dovrefjell, Norway.

Belgian travel and wildlife photographer Martin Dellicour comes eye to eye with the history of Earth embodied in a herd of muskoxen on the high plateaus of Dovrefjell, Norway.

Growing up in Ardennes, Belgium, visual artist and photographer Martin Dellicour developed an appreciation for the aesthetics of nature early on. Dellicour remembers childhood as taking place outdoors, simply observing. At age fifteen, Dellicour’s parents gave him his first camera, a Nikon F–501, which he regards as “a revelation where the decision of being a photographer was secretly made.”

After studying at the school of art in Liège, Belgium, Dellicour worked independently, producing travel photography, graphic design, and videography. Four-teen years ago, he opened his own creative agency, Studio Breakfast, and later the graphic design atelier C'est Beau.

Pictured is Dellicour’s heedful dance with a herd of majestic muskoxen in Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Norway—a winter landscape he describes as “an amazing and wild place.” The snow has a power of its own to Dellicour, one that can “change our perception to focus on the simple, essential things, and see the many questions of everyday futility.”

These muskoxen have a similar effect on Dellicour. “When you are in front of them, you feel like you’re facing the history of Earth. Out of time.” Paired with the white, minimalistic landscape, Dellicour demonstrates the transient experience of observation.

“When you are in front of them, you feel like you’re facing the history of Earth. Out of time.”

Dellicour desires to be close with nature, questioning the eyes and minds with which we observe. “It is an inner journey as much as an outdoor experience,” he says about his purpose in capturing natural settings.

“My main subjects are wildlife, nature, landscapes. But behind the subject, I am moreover fascinated by the light, the way light always surprises me in outdoor conditions.” Places visited hundreds of times appear different to the lensman every time. “Nature photography has this quality of keeping an element of unpredictability,” he says. “It’s exciting.”

“My main subjects are wildlife, nature, landscapes. But behind the subject, I am moreover fascinated by the light, the way light always surprises me in outdoor conditions.”

Monochromatic atmospheres characterize Dellicour’s artwork. “The subject is not always recognizable but more of a suggestion.” The indistinct interplay between the wild animals and the still landscape becomes the crux of his work, the essence of what makes him a unique artist. It’s the unpredictability and rawness that draws the viewer to question what visual experience we’re having and why.

Dellicour evaluates his own work through the eyes of others. “It’s quite difficult to know if I’ve got talent or not,” he says. When he finishes one project, he’s off to the next in order to keep the creative mindset moving. Artwork then becomes a mode of transport between ideas, in hopes that others will be able to identify something inside of themselves that reacts to the visual aesthetic presented. In this way Dellicour main- tains freedom of expression, which allows viewers to write their own stories and empathize with his work.

His life, seemingly complex—ever engaging with a new subject in front of the lens, perpetually on the road—Dellicour nevertheless remains simple in lifestyle. “I try to get the best of all the little and big things that happen in my life”...walking in forests, making bread, sharing time with his wife and son. “Sometimes we can’t see the evidence,” he says, “we focus on the bad things or don’t even take the time to focus on anything.” So keeping an element of play is essential to Dellicour’s life, the balance of contemplating, creating, yet liberating via the visual arts. △

Slow Architecture

Spawned by the slow food movement, slow architecture reflects a return to the roots of the master architect tradition

When Italy’s first McDonald’s poised to open in 1986—a stone’s throw from the fabled Spanish Steps in Rome, no less—it ignited not only a protest but a counter-revolution. Italians, so proud and protective of their exquisite centuries-old cuisine and culinary traditions, rebelled against not only the first McDonald’s in their iconic city but the decades of culinary collapse spawned by the “fast-food revolution” of the 1950s—that reduced food, along with its preparation and consumption, to its lowest common denominator. Political activist and journalist Carlo Petrini took part in the initial protest and is credited with the creation of the slow food movement. Three years later, in 1989, the manifesto of the International Slow Food Organization was signed in Paris by delegates from fifteen countries with the goal of promoting local foods and time-honored traditions of gastronomy and food production. It opposed fast food, industrial food production, and globalization, with the goal of preserving traditional and regional cuisine, and encouraging farming of plants, seeds, and livestock characteristic of the local ecosystem.

From slow food came the whole “slow” movement, with slow cities, slow living, slow travel, slow design, and slow architecture—a label credited to the Japanese.

“It is a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better. The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed. Savoring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them. Doing everything as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible. It’s about quality over quantity in everything from work to food to parenting,” writes Carl Honoré in his 2004 book In Praise of Slowness, which has become the new-millennium bible of the movement.

"The Slow philosophy is not about doing everything at a snail’s pace. It’s about seeking to do everything at the right speed."

Environmental roots and “deep ecology”

So what is slow architecture? The Tvergastein Hut in the Hallingskarvet massif in Norway epitomizes the concept. It’s a simple wooden mountain cabin in harmony with its surroundings that took several years to build with appropriate, readily available local materials—think small carbon footprint. The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics.

A lifelong mountain climber and Norway’s most famous philosopher and a professor of philosophy at the University of Oslo, Arne Næss was influenced by the writings of seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher Spinoza and twentieth-century ecologist Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, the ground-breaking environmental science book published in 1960. Silent Spring documented pollution from the chemical industry and its detrimental effects on the environment, particularly birds, along with other negative human-caused environmental impacts. The book cartwheeled into scripture for the environmental movement of the 1960s.

Næss was convinced of the impending ecological disaster for planet Earth, and in 1969, he retired from his university position and built his Tvergastein Hut, where he lived and developed the philosophy of “deep ecology,” which sees the complex interconnection and web of all life-forms, objects, and events. Shallow ecology seeks solutions to economic problems through technological fixes; deep ecology demands fundamental economic, political, cultural—and spiritual—changes.

“It’s a whole different perspective of our place on Earth,” says Carolyn Strauss, a California-born, Columbia-educated architect who created the Amsterdam-based slowLab, a research platform for slow knowledge in design thinking and practice. “We work with individuals, architectural firms, architects, and students,” she says. “Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment. And understanding himself as one small part, and not a native of that ecosystem.

“It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things. We’re part of a much larger, complex system, which we can never fully understand. We tend to ignore that fact. And this leads to our fragmentation of the world, versus gestalt thinking—perception of the whole and interdependence. This type of human-centered thinking and fragmentation has generated a lot of the problems in the world,” Strauss says.

“[Arne] Næss’s hut isn’t an aestheticized version of anything. For him the beauty and quality comes from the environment....It’s about understanding ourselves as part of larger systems and moving humans out of the center of things.”

— Carolyn Strauss

Næss’s hut was built from 1937 to 1943, the pieces carried by horse and sled in sixty-two trips up the mountain. He also built a smaller climbing hut on the very edge of a cliff that required one to enter by climbing up through a trapdoor in the floor. Næss and his mountaineer companions climbed and dragged the planks and other materials up the mountain wall to build it. Næss died in 2009 at the age of 96. He lived at his cabin full time—this was no second home.

"The idea of slow architecture includes proper context, materials, sustainability, and affordability while still retaining aesthetics."

Spas and churches

On the opposite end of the slow-architecture spectrum is Therme Vals, a hotel/spa complex in Vals, Switzerland, built over the only thermal springs in the Graubünden canton. The architect was Peter Zumthor, who received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2009. Completed from 1993 to 1996, the building is made from stone taken from the mountain, plus concrete and glass. Designed to look like a cave or quarry-like structure, it has a turf roof and resembles the foundations of an archeological site, half buried into the hillside.

The locally quarried Valser quartzite was the driving inspiration for the design, and the building’s cladding is made from 60,000 one-meter-long thin slabs of the greenish-gray stone. Zumthor was fascinated by the mystic qualities of a world of stone within the mountain. He wanted to capture the light and darkness, the light reflections on the water and steam-saturated air, the unique acoustics of the bubbling water in a world of stone, the feeling of warm stones and naked skin—all to enhance the ritual of bathing. So that time would be suspended for those enjoying the baths, Zumthor wanted no clocks in the spa, but three months after the opening, he was pressured to install two small clocks. Zumthor carefully designed a path of circulation to lead bathers to certain predetermined points with areas and views to enjoy along the way. “The meander, as we call it, is a designed negative space between the blocks, a space that connects everything as it flows throughout the entire building, creating a peacefully pulsating rhythm. Moving around this space means making discoveries. You are walking as if in the woods. Everyone there is looking for a path of their own,” Zumthor explains.

A Spanish icon and UNESCO World Heritage Site, Barcelona’s extraterrestrial-looking Sagrada Familia basilica and Roman Catholic church is a classic and very literal example of slow architecture—still under construction 120 years after architect Antoni Gaudi first began it.

Urban and third-world slow architecture

Japan is among the leaders in slow architecture, and a renowned, award-winning example is Hillside Terrace in Tokyo’s trendy Daikanyama neighborhood. This internationally famous residential-commercial complex spanned three decades in its construction and evolution. Its creator, Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, was awarded the Prince of Wales Prize in Urban Design for reflecting the changes of time and giving life to the urban scenery. He also received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1993—a year after completion of Hillside Terrace.

“The flow of time can be measured against its diverse buildings and their relationship to the city of Tokyo as it grew to envelop them,” writes Maki. “The singular sense of place that people strolling among the various buildings and outdoor spaces of Hillside Terrace feel is no accident. It is the result of a deliberate design approach that has created continuous unfolding sequences of spaces and views, taking advantage of the site’s natural topography and, indeed, enhancing it with subtle shifts in the architectural ground plane.”

Butterfly houses

From the Norwegian Alps to the rainy highlands of northern Thailand, the architectural firm TYIN tegnestue, based in Trondheim, Norway, performs humanitarian aid through architecture. Their slogan is “architecture of necessity,” but that still embodies aesthetics. Started by five architect students from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, the firm’s third-world projects are financed by more than sixty Norwegian companies, as well as private contributions. TYIN has worked with planning and constructing small-scale projects in Thailand. “We aim to build strategic projects that can improve the lives for people in difficult situations. Through extensive collaboration with locals, and mutual learning, we hope that our projects can have an impact beyond the physical structures.” The architects use such readily available materials as old tires and locally grown bamboo.

“The Soe Ker Tie House is a blend between local skills and TYIN’s architectural knowledge. Because of their appearance, the buildings were named ‘The Butterfly Houses’ by the Karen workers [an ethnic group from southeast Myanmar]. The most prominent feature is the bamboo weaving technique, which was used on the side and back facades of the houses. The same technique can be found within the construction of the local houses and crafts. All of the bamboo was harvested within a few kilometres of the site,” write the architects on their website, tyinarchitects.com. “The majority of the inhabitants are Karen refugees, many of them children. These were the people we wanted to work for.” The architects hoped to foster a more sustainable building tradition for the Karen people in the future.

Form follows function

“Anybody who is practicing architecture right now, and has been practicing the last thirty years, has seen the profession become so much about style, form-making,” says Colorado architect ml Robles of Studio Points Architecture + Research in Boulder. “Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

“Form follows function,” was the mantra of twentieth-century “starchitect” Louis Sullivan, who admired Henry David Thoreau and Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80–70 BC), who said a structure must be solid, useful, and beautiful. Sullivan’s assistant was Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Form is the result of special interactions of space. If you start with form, it’s very limited.”

— ml Robles

“You don’t start with the box and stuff everything in it,” says Robles, who explains that the three-dimensional modeling computer program SketchUp has become the fast food of architectural design for too many versus careful, thoughtful design.

“So much of what’s happened in the last thirty to forty years was about consumption,” says Robles. “What’s happened is that architecture has become a commodity. So you’ve got, sort of built in, this turnaround—anything that’s a style is going to be out of style...and that’s why we have the crazy environments that we have, and most people are so dissatisfied with their built environments. It’s because they have been designed for a little tiny space in time, with little regard for the past, or really, a long-term future. They’ve been designed for the moment.”

Given all that, Robles says, “Slow architecture, I think, was a pushback to architecture that was about a trend, a pushback to architecture or urban development that was about erasure, and it was a pushback to the commodification of interior finishes and furniture.”

Sustainability and sensibility

The other thing that happened, says Robles, was the sustainability movement, “which was trying to reground the built environment—to be responsible.” So there are LEED buildings, green buildings, and gold buildings. “I think what is happening—and slow architecture is illuminating this—the thoughtfulness of doing what architecture has always been doing is becoming important again. It’s kind of sad that that’s the way the profession has gone.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period. That those things now show up under a label is an interesting reflection of our time, in that we need to be reminded of what architecture is. Those of us who practice architecture in this way have always known.

“The idea of thoughtful, responsible, meaningful—that’s what architecture is. That is the definition of architecture in the master tradition, period."

— ml Robles

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building; you’re in wonder, awe, you’re pulled through the space, usually by light, and you’re changed,” Robles says. “This happens to people when they go into cathedrals. Amazing places where people just, ‘Whoa.’ It happens when you go into a museum, or Union Station downtown in L.A., or Grand Central Station in New York. That’s the essence of slow architecture. What it does to the world. That’s what great architecture does. It causes you to pause and be present.” △

“If you’ve ever entered a building and you catch yourself and realize you have slowed down just to be in that building...that’s the essence of slow architecture.”

— ml Robles

Geometric Cabins on the Steep

Reiulf Ramstad Architects' Røldal Cabin design preserves as much of the surrounding Norwegian landscape as possible

Anytime an email from Reiulf Ramstad Architects (RRA) shows up in our inbox that mentions the Oslo-based architect and "cabin" in the same sentence, we are all ears. He had us as "preserving the surrounding landscape"... again.

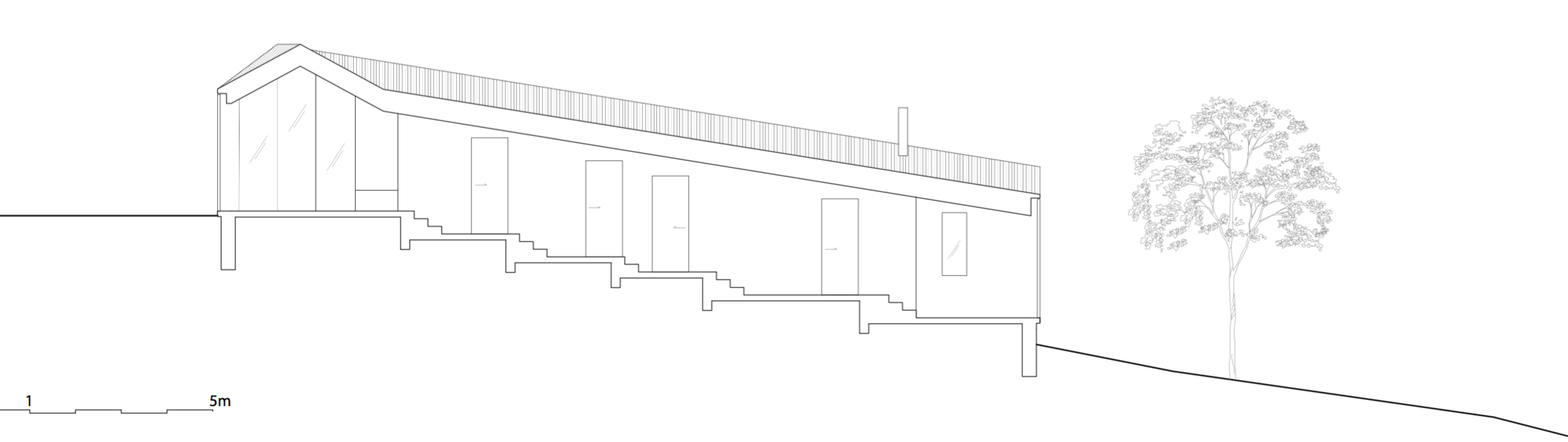

This time, RRA has designed a set of two cabins in Røldal, Norway. Once again, Ramstad's architecture stands simple yet bold. The Røldal family vacation home is recognizable for its compact, defined, and geometric shape. The objective of preserving as much of the surrounding landscape as possible resulted in the design of two volumes: a main cabin (63 square meters; 678 square feet) and a much smaller annex (11 square meters; 118 square feet) that keep a dialogue with the encompassing nature.

Dividing the structures also answers the need for the flexibility of being able to accommodate different family compositions in separate spaces. The articulated section is adapted to the steep terrain and is assigned to create interconnected floors and capture the views of both the forest and the hillside. △

Naked Naust

A dramatic cabin by Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch on Norway's wild Vega Island

Inspired by Norway’s traditional boathouses, Swedish architect Erik Kolman Janouch plants a cottage into Vega Island’s barren landscape—its design so minimal, it becomes dramatic.

“It’s basically just two ordinary pitched roofs,” architect Erik Kolman Janouch describes the Vega Cottage on the namesake Norwegian island. But the simple elegance of this small wooden cottage that blends so perfectly with its wild and forbidding landscape is, in itself, spectacular—not to mention the boldness and care in siting it there. What’s more, it is exactly what could be expected in this coastal region of Norway.

Not far from the house, by the seashore, stand a few of the colorful traditional boathouses—naust—found throughout Norway’s long Atlantic coast. With origins in the Viking era, this building type has withstood the test of time and weather with the island’s extremely rough climate. So, looking for another architectural typology for the Vega Cottage seemed like a futile enterprise for its Swedish architect of Kolman Boye Architects in Stockholm.

Casual observers might also miss the second most striking architectural feature of the Vega Cottage—its windows. At first, the house’s windows might appear like ordinary rectangular openings in a wall, covered with glass. But that’s just scale and perspective playing tricks, since the barren landscape of Vega Island offers little else of human scale for comparison. Standing directly in front of the house—where one’s cheeks quickly turn rosy from the cold Atlantic wind—an adult visitor can stand head to toe in the huge windows and absorb the majestic landscape. Buffeted by the wind and swept away with the dramatic views, one realizes that the windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island.

"The windows are what this house is all about. They showcase the grandeur of the island."

A Place Apart

Vega is home to 1,200 people and lies roughly an hour by ferry out in the Atlantic from the tiny city of Brøn- nøysund on the west coast of Norway, just south of the Arctic Circle. The cottage’s site is not much more than a farmstead, marked on the map as Eidem.

This is where the man who commissioned this house, Norwegian theatre director Alexander Mørk-Eidem, has his roots. Born on the island, he has lived most of his life on the mainland, and for the past ten years in Stockholm, Sweden. That is also where he met the architect. He approached Kolman with his idea for a country house or a cottage, commonly known in Norway as a hytte. A small and simple residence in the countryside where you go on weekends and during vacations to relax and enjoy nature... something with which Norwegians, blessed with a country of stunningly beautiful mountains and fjords, seem to be obsessed.

The end of the world, as Vega feels, seems like the obvious place for a director of the stage to seek peace and quiet and to find inspiration. Mørk-Eidem jointly owns the house with his siblings, a brother and a sister who now live in London and Oslo. The house is intended as a place for solitary retreats, but also for family gatherings, since an uncle and cousins still live on Vega.

“Inside, the house is neutrally furnished to allow for nature to...” Mørk-Eidem starts to explain when I visited the house, only to get interrupted by his architect: “It’s like three paintings. There is no need to adorn the walls.”

The Cast of Characters

What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape. It doesn’t take a stage director to reach that conclusion. Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless. On the other side of the windows of the combined living and dining room lies the mighty Trollvasstind mountain, 800 meters (2,625 feet) high with a ridge that’s hidden behind milky white clouds. In the other direction the Atlantic Ocean and open sea stretch all the way to Labrador in Canada.

“What they mean is that the house is built to be a minor character—the lead is reserved for the surrounding landscape... Trying to cast this drama in any other way would have been pointless.”

Kolman recalls the first time he came to the island and the site, after having accepted the challenge of designing the house: “I went there in January, which is the worst time of year, weatherwise. It was pitch dark and freezing. Shockingly freezing, really. I wasn’t prepared for how harsh the climate would be.”

But nature can be kind on Vega, too. At milder times of the year, when the tide comes in during the day, the sand at the shoreline that had previously been heated by the sun warms the shallow water, allowing for some appreciated beach life. But the weather changes quickly here: from calm to a wind you can lean against in a matter of minutes. It is wise never to leave the house without the proper attire: mittens, Wellingtons, and a decent raincoat.

In contrast to the adventurous landscape and weather of Vega, the cottage interior is serene with a neutral color palette to enhance the tranquil atmosphere. Practically everything inside the house, from the walls to the bed linen, is white. The architect thinks it gives the house a hotel-like quality.

The Right Stuff

Kolman met his client through a mutual acquaintance in Stockholm. Mørk-Eidem had been looking for someone to build the house for quite some time. Realizing what a challenge it would be on this particular site, he pictured someone young, eager to take on the assignment for the experience, and Kolman fit the bill.

In addition to being one of the partners of Kolman Boye Architects, Kolman also runs a construction firm. A lucky combination since all the contractors Mørk-Eidem approached for a tender had simply refused to answer. “There was nobody who could see any joy in trying to do the impossible,” Mørk-Eidem explains.

Kolman proved to be different. In the Vega Cottage he saw nothing but an enticing challenge. Building the house on Vega was possible, but it took five years and twenty-three Stockholm-Vega round-trips by car for the architect. A total distance, he figures, that roughly equals a trip around the equator. True or not, one trip by car from Stockholm to Vega is long, time-consuming, and not very pleasant.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house had always stood on this site,” Kolman says. “What fascinates most people who come here is that you get the feeling that it’s grown out of the bedrock.”

Building on the bedrock and being gentle with the landscape also made the construction difficult. A road had to be built to the site, and building material laboriously towed over the bedrock the house stands on—not to mention the efforts to transport and install the windows. The panes are 40 millimeters (1.57 inches) thick to withstand the storms and high winds that would shake and shatter thinner glass. Residents can enjoy the spectacle outside from a quiet, warm, and cozy house, cheered by the hearth that is the heart of the lower-level’s social area. “They’re not something you can break easily,” Kolman says about the windows. “In fact, you can jump on them and nothing will happen.” Staying at the Vega Cottage, I was glad the project was graced with such a persistent architect-builder—the landscape is beautiful, but I was happy to keep the elements of nature where they belong—on the other side of the glass.

“It was really important to build the house without doing any damage to the landscape and to make it appear as if the house has always stood on this site.”

Other than the pitched roof, this is a rather minimalistic house—or as Kolman says, “There is nothing that juts out, so there is nothing for the wind to grab on to.”

There is not even a railing around the terrace outside the lower level’s two bedrooms. “My sister wondered when they would be put in place,” Mørk-Eidem says. “They never will be,” he declares, adding, “This is a childproof house in the sense that nothing can be broken.”

If nothing can get broken, theoretically nothing will need to be fixed. To keep maintenance on the house to a minimum during holidays and vacations, Mørk-Eidem and his architect opted for weatherproof solutions for the house. At one stage in the project they considered black facades. But when I visited, a year after completion, the unpainted facades, which were only treated, already had their gray patina. Houses age fast on Vega.

“Houses age fast on Vega.”

The cottage owes much to vernacular architecture, but the local building tradition has always emphasized protection from the elements of nature. The island’s old buildings, placed wherever there is shelter from the storms, all turn their backs to nature and to the extreme weather. “You get very unsentimental living out here,” Mørk-Eidem tells me. “You get used to this nature, and you look at it as a kind of antagonist.”

“You get very unsentimental living out here.”

He proceeds to tell how his father reacted when he first came to the house. As an adult, Mørk-Eidem senior moved to Oslo and hadn’t lived on the island for decades. “At first, he was suspicious,” Mørk-Eidem recalls, “because he’s never been used to sitting inside and just admiring the view. For him it was a really different experience to come to a place he knows so well but to see it from an entirely new perspective.”

Hearing that this outpost can give even natives new perspectives is a testament to the qualities of this house that makes the architect say, without the slightest hesitation, that he would gladly take on the logistical and psychological challenges of an assignment like this again. △

Hideaway Cabin

Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta in Norway

Seemingly growing from the mountain, the impossibly small Åkrafjorden Hunting Lodge by Snøhetta shelters up to 21 people. The Norwegian firm Snøhetta creates architecture, landscapes, interiors and brand design. And in this case, incredibly small architecture with a big task.

Family shelter

The project was commissioned on family farmland by Osvald Bjelland, who is chairman and CEO of the global business advisory Xyntéo and founder of The Performance Theatre, a leadership think tank.

The challenge in designing the Åkrafjorden hunting lodge on a fjord, high in the mountains above the village of Etne in Hordaland, Norway, was indeed its small size in the face of its intended use: The mountain hut was to be maximum 35 square meters (ca. 377 square feet), with the capacity to shelter up to 21 people (the same number of beds as at the family's farmhouse down in the village). Plus, the off-grid structure with no running water needed to look like it had always been there.

Only accessible by foot or on horseback, the remote lodge’s setting is beautiful, isolated, beside a lake in the untouched Nordic wilderness of West Norway.

One important part of the design concept was to integrate the hut into the landscape. Thus, the small hut’s shape, orientation and materials are influenced by the terrain’s characteristic composition of grass, heather and glacial rocks. In winter, the cabin becomes another brown fleck — like the rocks — in mounds of snow.

Modern expression of ancient traditions

The structure consists of two curved steel beams, covered with a continuous layer of hand-cut logs of timber — a fusion of modern architectural expression and the style of traditional Norwegian mountain cabins. The roof, with its organic form, “grows” out of the landscape and is overgrown with grass. The materials of the facades are local stone, tar treated wood and glass.

To make room for a surprisingly large number of guests in such a tiny space, the architects found inspiration in ancient lodging traditions: The space in the center serves as gathering place, and the beds along the walls provide a spot to sit comfortably around the middle of the room in the evening — one piece of furniture for socializing, eating and sleeping. A narrow nook by the entrance accommodates cooking equipment and storage. △

Trollstigen Visitor Center Norway

Designed by Reiulf Ramstad Architekter, the visitor center and viewing platform dramatically enhance the experience of Norway's wild nature and landscape.

Oslo-based Reiulf Ramstad Architekter (RRA) has a reputation for bold, beautifully simple Scandinavian architecture — from groundbreaking civil buildings to private Nordic holiday lodges — all bold and unhesitating in form yet free of pretense in their assertion in the landscape.

Alpine Modern has previously covered one of Ramstad's residential designs, the V-Lodge.

Now, German photographer Lars Schneider of Outdoor Visions shot one of RRA's public works for us, the Trollstigen Road Visitor Center. Opened in 1936, the Trollstigen National Tourist Route stretches 106 kilometers (66 miles) through West Norway's mighty nature. Ramstad's firm designed the visitor center to enhance the experience of rugged mountains, waterfalls and deep fjords.

Lars Schneider's report from the road

"I was on assignment in Norway, shooting for an outdoor clothing brand. The night I captured these images, after the client and the models had left for the hotel at one o'clock in the morning, my assistant and I decided to spend the rest of the night in the mountains. The sky looked promising, and the sun rose at 3:30 am that time of year.

"We lingered around the visitor center for a very long time. Besides taking in the spectacular views and the sensational light, we quite enjoyed the fact that we had all this to ourselves. During the day, droves of tourists swarm Trollstigen, eager to take tight hairpin turns winding up and down the steep mountainsides and to take in the untamed Nordic vistas. Not having to share all this with anyone was immensely gratifying.

"The architecture is grandiose. Everything very sophisticated, rectilinear, pure, considered... yet beautifully assimilated into the scenery." △

Out of Town

The modern country escape a New York City couple builds in the Catskill Mountains quickly becomes home base

When a New York City couple builds a Scandinavian-modern weekend retreat in Bovina, New York, the center of their work and social lives unexpectedly shifts to the small community in the Catskill Mountains. These days, the native Nordics use their Brooklyn apartment for short getaways to the city.

After both of her parents died of cancer, Jeanette Bronée, an interior designer in New York City, completely turned her life around. She became a health coach and founded the Path for Life Self-Nourishment Center to teach people about their own power to heal the body. Being mindful of self-nourishment and tending to your soul is never easy when living with habitual stress, especially in a metropolis of millions. For Bronée, who grew up in Denmark, reawakening that sense of taking care of oneself and the remembrance of what being outside feels like was pivotal. “Nature has always been a big part of my life, even as a child,” she says. She needed to get out of town, at least on weekends.

Two Nordics in New York

Then, six years ago, Bronée met Torkil Stavdal at a design event. The Norwegian photographer, who travels the world for advertising clients and magazines, had recently moved to New York City. “We started talking about kitchens because we both love food and cooking.” She giggles at this memory of their first encounter. The two spent the evening talking about how important the world we create around us is to feeling nourished. “So not long after we met, I told Torkil about my desire to get out of town for a weekend getaway.” Having just arrived, the newcomer to the Big Apple was reluctant at first. He craved the urban experience. But the photographer soon caught up to Bronée in needing periodic time-outs from New York City.

Their search for a country escape narrowed to the western Catskill Mountains, approximately three hours north-north-west of New York City by car. “We wanted to get far enough out of the city—not just Woodstock, which is a weekend destination—but far enough to get a sense of the area while fitting it into our budget,” Stavdal says. He admits to burning through “a lot of weird realtors” before finally connecting with an agent who smartly sent them on a drive around Bovina, New York. “We fell in love with the picturesque little town before even seeing the first property,” he remembers. “Then she showed us a place called the ‘Secret Meadow.’ When we walked in, it was like a little jewel in the middle of nature. It’s very beautiful land.” The Stavdal-Bronées were allured at first sight by the tree-rimmed rural acreage at the end of a 500-foot-long (152-meter) private driveway.

“Then she showed us a place called the ‘Secret Meadow.’ When we walked in, it was like a little jewel in the middle of nature. It’s very beautiful land.”

Creating something new

Stavdal and Bronée knew from the start that they wanted to design and build a new home rather than buying and restoring one. Bronée substantiates that decision with her European heritage: “We build stuff!” She laughs, then continues more contemplatively, “My dad always built our houses in Denmark, so I was used to creating something based on what we needed and what we wanted in our lives.”

“My dad always built our houses in Denmark, so I was used to creating something based on what we needed and what we wanted in our lives.”

To help them realize those needs and wants, the European expats enlisted New York City architect Kimberly Peck, who worked for Bronée when she had a design studio in the city. “Kimberly was sensitive to what we wanted to create because we already knew each other from the past,” Bronée says. “Part of coming up here was the distinct vision of wanting to implement design ideas I’ve had over the years for others, and now I finally had the space to create something for myself.”

The couple, who share a deep appreciation for midcentury-modern design, needed to decide on an architectural style for the Bovina house-to-be. “I’m inspired by monolithic Japanese concrete buildings,” Bronée says. “I love that very severe design.” Her husband, on the other hand, dreamed of a cozy Scandinavian cabin, modern and flooded with light. After considering (and dismissing) the idea to build a modern prefab, the two compromised on a house that Bronée says “feels like a loft and a barn, so this was the perfect combination.” On the outside, the Nordics both wanted the dramatic, modern aesthetic of a black facade that would remind them of their common Scandinavian roots. “Back home, the cabins and houses are black,” says Stavdal, referring to the traditional dark exteriors of Scandinavian homes typically brought about by a mixture of linseed oil and tar.

Building for light

Keeping the house low maintenance was not the only reason they chose a steel exterior. “Aesthetically, mixing this style of building with that material was fascinating,” Bronée notes. “It created this monolithic feel to it, and in certain light the house almost looks velveteen. It doesn’t look like corrugated metal—it looks strangely soft.” The former interior designer, who back in the day created contemporary spaces for fashion boutiques, showrooms, and in-store shop concepts, was also inspired by the many Dutch architects currently using corrugated metal on modern houses. But merging the Nordic-inspired modern exterior with conventionally sized American sliding windows would not have worked. “In Scandinavia, we have longer slit windows, so we were taking elements of our heritage and mixing it in. We also wanted that European idea of pushing the windows out in autumn.” After a pensive pause, Bronée adds, “I think our architect thought we were half nuts with some of the things we wanted, but she was up for it.” And Stavdal adds, “I’m Scandinavian; I’m light-dependent. Having three huge sliding doors letting nature in is a huge thing for me. I need light. Part of our living up here is that we as Scandinavians come alive as the sun comes out, so we spend most of our time outside.” Much of their everyday life happens on the spacious deck. Stavdal even installed an outdoor shower and bathtub. “As soon as the frost is gone in the spring, we don’t shower inside anymore. We have a little tub out there.”

“Part of our living up here is that we as Scandinavians come alive as the sun comes out, so we spend most of our time outside.”

The light junkies, however, elected to have no windows at all on the driveway-approach side of the house. The windowless front added further to the monolithic impression of the house. And they liked the idea of a hideout. It’s not until visitors walk into the house that they get to see the magnificent view of the secret meadow, with the Catskills beyond. “It illustrates the idea of bringing the outside in,” says Stavdal. “The land opens when you get into the house.”

Building efficiency

Above all, the Stavdal-Bronées wanted to build an energy-efficient house from materials that were both economical and sustainable. The winters can get extremely cold in the Catskills, so insulating the house well was critical. Throughout the design and building process, Stavdal gained a tremendous amount of knowledge about building materials and their different properties, which he believes ultimately determined many choices and decisions during the construction.

A timber frame salvaged from a nineteenth-century barn, restored and transported in pieces to the building site, forms the main structure of the house. The barn frame was raised first—“the good old way,” Stavdal says. “They put it together on the ground, and then five guys raised it up with ropes. That was so cool.” The barn frame erected, they installed structurally insulated panels—or SIPs—that were prefabricated and delivered in sections. The vertical pieces, which are six inches (ca. fifteen centimeters) thick and four feet (ca. one and one-fifth meters) wide, rest on a sill around the exterior perimeter. Toward the top, the panels were cut to accommodate the shape of the gable.

“We stacked the SIPs around the house...like Legos. It’s a simple way of raising a house. The exterior of the house was completed in only three days.” Making all joints between the SIPs and around windows and door openings extremely airtight paid off: “Our house is so warm in the winter, and our heating cost is a fifth of the usual cost up here,” Stavdal says.

The 1,945-square-foot (181-square-meter) house sits on a concrete slab with integrated radiant heating. Polished and left exposed, the top of the slab serves as the interior flooring surface. Once the contractors had finished the exterior of the house, Stavdal completed all the interior work himself. He built the second story’s floors and ceiling and the stairs from reclaimed barn wood. Furnishings are sparse but comfortable. A sleek black woodstove centers the living room. On the opposite side of the wide-open great room lies the dream kitchen Stavdal and Bronée started to plan that night they met in New York City.

Space and time for creativity

“Being up here, I feel more creative with the things I do,” the nutritionist says. “I get ideas for articles and things I want to teach and communicate because I have more thinking time but also because I have a big kitchen—a crucial part of the house—for having people over and for sharing a meal.” Bronée, who develops recipes in her Bovina kitchen, grows her own vegetables and frequents the area’s organic and free-range farms. “It’s become a very food-oriented place,” she says. “We also built a yoga platform in the woods. The whole thing feels like it supports that nourishing lifestyle of reflection and touching base with myself when I’m here and being able to create space for thinking and not so much doing but...being”

The locals are peers

At the time they bought the land, the Scandinavian couple didn’t know anything about the local community—a huge bonus, it turned out. “Our social life has just transferred to Bovina,” Stavdal says about their unexpected sea change in lifestyle. “We work from Bovina. Jeanette writes a lot here. She wrote her book up here. Literally, New York has become the getaway, and this has become our home.” The Nordic transplants quickly felt like locals in Bovina.

“I have a lot of peers here. Photographers are a dime a dozen—we are littering the place,” he quips. “This seems to be a playground for the creative community. We have a lot of friends living in the Catskills who are cinematographers, directors, photographers...we find like-minded people.” He doesn’t sorrow over losing the city folks who are unwilling to make the long drive. In Bovina, a small community of 600 or so that is still a relatively poor area compared with the rest of New York State, he doesn’t notice a big divide between weekenders and locals, and weekenders don’t expect to be catered to by the locals. “The Catskill Mountains are undeniably becoming a destination for New Yorkers. Instead of going to the Hamptons, they’re going to the Catskills,” Bronée says about the “New York expats” who flock to the area to create businesses in the hospitality industry or to take up farming. “Some of these dairy farms up here have now become artisan dairy producers who make good cheeses, all that good stuff.” She remembers worrying initially that options for buying fresh, quality food were limited, but upon discovering a small co-op, the healthy-living sage knew she could stay here. Meanwhile, the couple has cultivated a food orchard on their own property, with a 1,000-square-foot (ninety-three-square- meter) kitchen garden.

“The Catskill Mountains are undeniably becoming a destination for New Yorkers.”

Urban life, by contrast, feels more “hour to hour,” Bronée contemplates. The couple now drive to New York City for external inspiration. “We work in both places, but the city has a different energy and pace,” her husband adds. “We ended up using the Brooklyn apartment more to go to sleep and work. While here, we work and live. So this feels more like a home.” △

“We ended up using the Brooklyn apartment more to go to sleep and work. While here, we work and live. So this feels more like a home.”

Ice Wide Open

Photographer Chris Burkard finds joy in near-freezing waters just inside the Arctic Circle

When surf photographer Chris Burkard wearied of shooting at tropical beaches and extravagant tourist destinations, he sought out the world’s most remote, stormiest coasts—and found ultimate gratification in Arctic waves. Chris Burkard wouldn’t blame you if you called him crazy for finding absolute joy in surfing just inside the Arctic Circle.

In his talk at TED2015, the renowned photographer shares a story that finds him in the near-freezing waters of Norway’s Lofoten Islands. Chasing perfect waves in the icy ocean with a group of surfers, he could feel the blood leaving his extremities, rushing to protect his organs. “Pain is a kind of shortcut to mindfulness,” he quotes the social psychologist Brock Bastian. The TED session is fittingly titled “Passion and Consequence.”

“Pain is a kind of shortcut to mindfulness.”

His parents didn’t think “surf photographer” was a real job title when Burkard told them at age nineteen that he was going to quit his job to follow his dream of working (and playing) at the world’s most exotic tropical beaches. The self-taught photographer set off in search of excitement but found only routine. A seemingly glamorous career of shooting in dream tourist destinations soon left him ungratified. Constant Internet connection and crowded ocean waves slowly suffocated his spirit for adventure.

Perfect waves in intoxicatingly unforgiving places

“I began craving wild open spaces,” Burkard tells his TED audience. Once he grasped that only about a third of the Earth’s oceans are warm—a thin band around the equator—he began to look for perfect waves in places that are cold, where the seas are notoriously rough. Places others had written off as too cold, too remote, and too dangerous to surf. Places like Iceland.

"I began craving wild open spaces.”

“I was blown away by the natural beauty of the landscape, but most importantly, I couldn’t believe we were finding perfect waves in such a remote and rugged part of the world,” he says. Massive chunks of ice had piled on the shoreline, creating a barrier between the surf and the surfers. “I felt like I stumbled onto one of the last quiet places, somewhere that I found a clarity and a connection with the world I knew I would never nd on a crowded beach.” The icy ocean his new muse, the artist was again intrigued by his subject.

Cold water always on his mind now, Burkard’s newly invigorated career took him to such intoxicatingly unforgiving environments as the frozen wilderness of Russia, Norway, Alaska, Chile, and the Faroe Islands. He spent weeks on Google Earth trying to pinpoint any remote stretch of beach or reef and then figuring out how to actually get to it.

Hypothermic yet happy

In a tiny, remote fjord in Norway, just inside the Arctic Circle, Burkard and his crew encountered a place where some of the largest, most violent storms on Earth send huge waves smashing into the coastline. He was in near-freezing water taking pictures of the surfers (who knows how he managed to push the camera shutter-release button), and it started to snow. He was determined to stay in the water and finish the job, despite the dropping temperature. He had traveled all this way, after all, and found exactly what he’d been waiting for. Wind gushed through the valley. Steady snowfall escalated into a full-on blizzard. Burkard lost perception of where he was. Was he drifting out to sea or toward the shore? Borderline hypothermic, his companions had to pull him out of the water. They told him later he had a smile on his face the entire time.

From that point on, the photographer knew every image was precious, something he says he now was forced to earn. The anguish out there on the icy water had taught him something: “In life, there are no shortcuts to joy.” △

“In life, there are no shortcuts to joy.”

Landscape, the Architect

The calm design of the V-Lodge in Norway responds to the down-sloping terrain

High up in the mountains of Norway, the V-Lodge's simplicity in design and choice of materials speak to its wild surroundings. “The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal,” Oslo architect Reiulf Ramstad says about the minimalist mountain house he designed for a family of six. “Its form is a dialog between the landscape and the client.”

"The building is lying on the terrain like a sleeping animal."

Ramstad’s architecture speaks to the people and the place he creates it for. The self-described generalist, who designs modern homes as well as hotels, churches, and civic projects, says today’s one-size-fits-all designs may be rational, but, “Architecture is more than an economic business; it’s a humanistic business. The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals.”

Creating only what is essential, never more than necessary, particularly interests Ramstad. The V-Lodge a prime example: His clients, who enjoy nature and simply being together, away from their busy lives in the city, had originally commissioned a much larger house to be built on their land 200 kilometers (124 miles) northwest of Oslo. Discussing the project with the architect, however, they understood that a smaller, more sustainable cabin would better suit their needs and accommodate a change in family composition and a mix of generations in years to come.

"The new luxury is not a materialistic luxury, but a luxury of how we want to live life and respect places, people, and animals."

The Right Man for Wild Territory

“We had found the most beautiful site on the outskirts of the Norwegian mountain area called Skarveheimen, a wild territory between the better-known and -visited Hardangervidda and Jotunheimen,” says Lene, who shares the remote retreat with husband Espen, their three grown children (twenty-two, twenty, and eighteen years old), and their eleven-year-old daughter (“our afterthought”). Plus, not to forget, labrador Vilma. (The family prefers we do not print their surname).

The couple had searched for the right architect for quite a long time. “Someone who could gently transform the landscape and, at the same time, preserve and strengthen the qualities of the site,” Lene says.

Influenced by two very different cultural contexts—Scandinavian and Latin—the Nordic architect’s business and design philosophies made him the right man. Born in Oslo, Ramstad, who received his Dottore in Architettura from the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, deliberately chose to study in Venice, Italy, to experience life without cars. He founded Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter in 1995, without previous experience. He has never worked for another firm. “It may not be the most rational way, but it’s a very interesting experience in that you have to invent most things,” reflects the credo of the now internationally recognized architect.

Lene, a graphic designer, and Espen, an executive in the gas and pipeline industry, handed Ramstad a long list of functional needs and aesthetic preferences along with a budget, but otherwise, they gave him free hand. “We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking,” Lene says.

"We wanted simple, ‘spartan’ architecture but with the luxury of running water and electricity for light, heating, and cooking."

Walking the Landscape Inside

The remote retreat sits near timberline at 960 meters (3,150 feet) above sea level, high above spread-out villages down in the valley. The architect took his own site survey, obtaining more precise data than the public maps revealed. “We needed finer measurements so we could create a better dialog between the building and the landscape,” Ramstad illustrates. “The building itself can follow the topography, instead of peaking and ruining the place.”

Guided by unspoiled mountain views and the directions of the wind and the sun, the V-shaped house design is Ramstad’s response to the landscape. While one side of the V sits on a horizontal level, the other side steps down with the terrain, resting close to the ground. “You can walk the landscape inside the house,” says Ramstad. The small scale of the rooms in this private wing reflects nature’s small scale right outside the windows there — small plants and trees, the snow lying close to the ground. “It’s a very simple way of responding to different scales and intimacy, to public and private spaces.”

"You can walk the landscape inside the house."

The horizontal wing of the 120-square-meter (ca. 1,300-square-foot) house accommodates the entrance and the main living area with the kitchen and the dining room. The other part, which follows the downward slope, houses the bathroom, three bedrooms and a lounge area at the far end. The V culminates with the glazed wall at the confluence of the two sections.

A Spatial Kaleidoscope

Ramstad’s design uses only about a tenth of the land, letting the rest be nature. “Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature,” Lene says. “We are carefully taking the terrain close to the cabin walls back to what it was, as if the cabin is growing out of the ground. Working with soil, stone, and vegetation is part of our life at the cabin.”

Ramstad perceptively oriented different elements of the structure toward distinct sights, offering views of different kinds of landscape. “The architecture is a spatial kaleidoscope,” he says. The floor-to-ceiling walls of glass create immediacy with the outdoors. “The glass cancels the barrier between inside and outside,” the architect continues. “Sitting in the living room is like having these huge landscape paintings that are actually views towards the mountains. So working with very subtle and slim glass details and without frames, the window becomes just a transparent layer, and not a window in itself.”

"Whether we are inside or outside the cabin, we are in close contact with nature."

The exterior is entirely clad in untreated, short-hauled pine; inside, walls and ceilings are paneled in pine plywood. “Using one material gives wholeness,” Ramstad says about the lodge’s minimalist appearance, which is also void of extra decorations. “When the wood oxidizes, it will have this patina that blends into the landscape, into the colors of the surroundings. The design and carpentry of fixed furniture and other features, including lamps, kitchen, bathroom, wardrobe, tables, and beds, was done by the owners themselves. Says Lene: “We like to design and build things together, and that is an important part of our leisure time.”

100 Days of Solitude

“Going to the cabin for weekends and holidays is definitely different from our life in Asker by the Oslofjord. A three-hour drive from home, and we are at the cabin, where we have everything we need for recreation — but not more than that,” Lene says. “However, the most important thing is being together, and at the same time having the freedom to be on your own.”

In winter, the family cross-country skis right out of the cabin’s door. In summer, they hike in the surrounding mountains. On warm days, they go for a swim in the nearby mountain lake or a dip in the River Lya. “This has definitely become the all-year cabin we wanted,” Lene raves. “We used it exactly 100 days the first year.”

The architect is equally pleased. “Spatially, this is not a very fancy project. It is very calm, yet at the same time, has very clear, distinct design solutions,” Ramstad says. “I’m very happy with it.”