Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

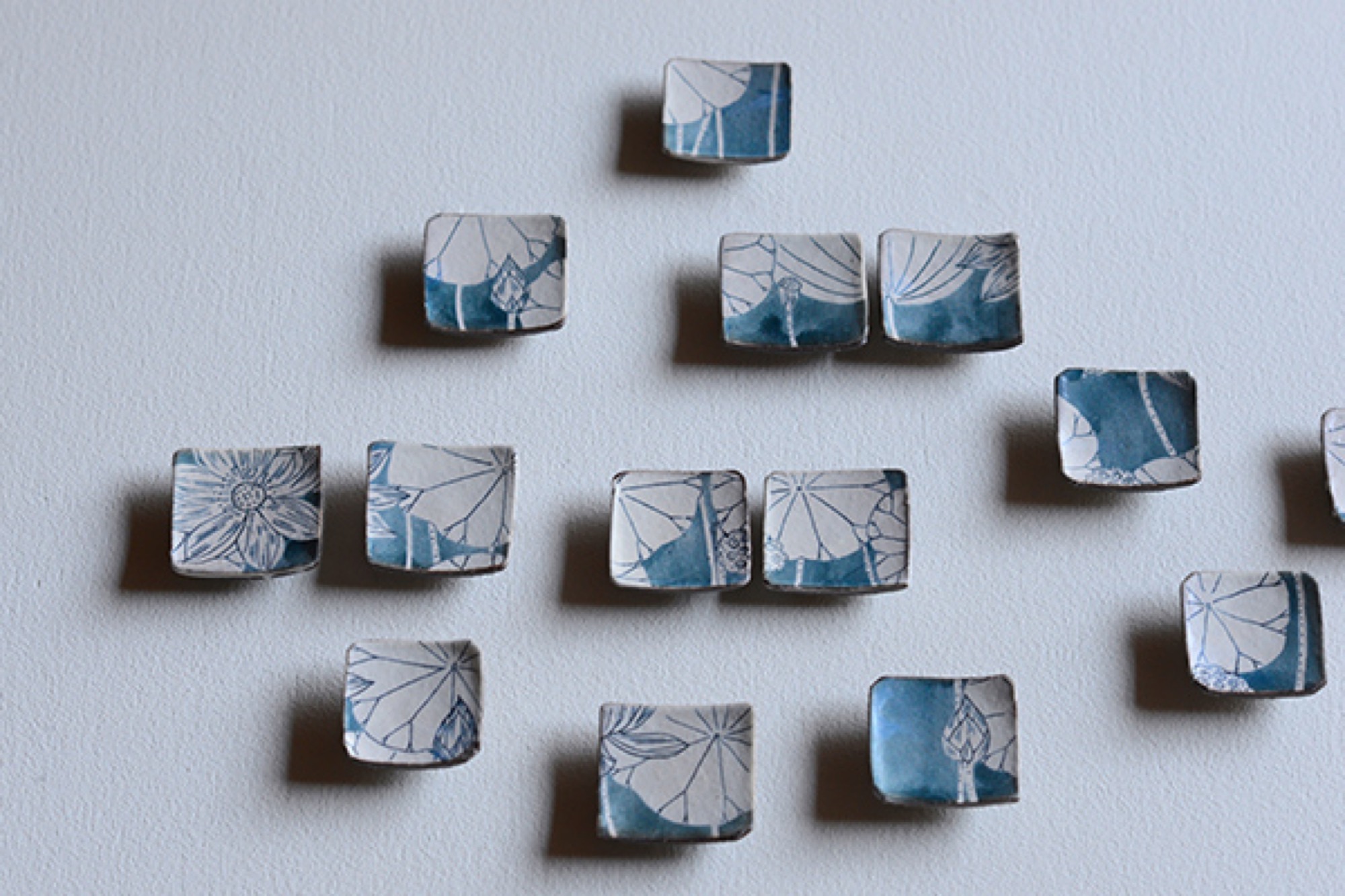

Minimalist Pottery in the Kyoto Mountains

An intimate visit with husband-and-wife pottery artists Momoko and Tetsuya Otani at their home and studio in Japan

The Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto departs not one minute late, travels almost 200 miles an hour, passes Mount Fuji on the way, and pulls into Kyoto’s vaulting modern station not one minute early. From there it’s 40 kilometers by car to Shigaraki, an industrial mountain town, where I’ve come to visit a ceramic artist whose work has transfixed me on Instagram for the past ten months.

Shigaraki is home to one of Japan’s “six old kilns.” The most admired pottery here—tea bowls and sake cups made from local iron-rich clay—is often misshapen and haphazardly glazed. Much is left to the felicitous violence of earth and fire in wood-fueled kilns. These clay items, used in the exquisitely calibrated tea ceremony, are prized for their imperfections, reflecting the wabi-sabi philosophy in which earthiness, transience, roughness and decay reveal the essential nature of the world.

Such is Japan: hyper-curated, thrillingly modern, clockwork precise—then offering you a tea bowl that seems primeval.

The ceramic artist I’ve come to see, however, is Tetsuya Otani, whose work departs so thoroughly from the Shigaraki style as to seem from another world. Otani’s hand-thrown porcelain chases the precision of machine manufacture. Its skin is smooth and naked, like that of a baby. I wanted to know why he was making such beautiful but plain stuff.

Right now, though, I have a few hours to kill, so I drive into the mountains to find the I.M. Pei-designed Miho Museum. The Miho is a kind of Japanese Getty, opened in 1997. It’s perched on a thick-forested mountain top like something a hermit might build if the hermit had several hundred million dollars. To reach it you walk through a hill via a gleaming, curving science-fiction-y pedestrian tunnel and emerge on a bridge that’s supported by a harp-string array of steel cables. The Miho was commissioned by an industrial-fortune heiress who also made time to found a sect in the 1970s, variously described as an art-centric religion and a sinister cult.

As traveler’s luck would have it, the museum is showing an astounding collection of ceramics by the 18th-century artist Ogata Kenzan, whose name means “northwest mountains.” His painted cups, bowls, and trays leave the viewer giddy, so varied and playful are they in style and form.

At home with Momoko and Tetsuya Otani

Five or so kilometers from the Miho is the home that Tetsuya Otani shares with his wife Momoko—also a gifted ceramic artist—and their three girls and a dog. It’s beautiful, with farmhouse mud walls and high wood beams that employ traditional temple joinery. Everything on the main floor revolves around the kitchen, which is far larger than usual in a Japanese house, reflecting the Otanis’ passion for communal cooking and eating with friends, many of whom also make pottery. The shelves, in the dining area and kitchen, are filled with both Tetsuya’s and Momoko’s pieces.

The work of Tetsuya Otani

Lately attracting attention among collectors in Beijing, Shanghai, and Taiwan, Tetsuya shuns both wabi-sabi imperfection and Kenzan decorative exuberance. Everything he makes is to be used, mostly in the kitchen or at the table: tiny matcha urns with clinking lids, curved-belly flower vases, delicately spouted teapots, tiny soy dispensers, little round boxes. The pieces are finely lipped and polished to a supple smoothness; their creamy matte glaze begs to be caressed.

Tetsuya’s pottery has thrown off all temptation toward decoration. The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because “things that work give pleasure.”

"The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because 'things that work give pleasure.' ”

He studied in Kyoto, hoping to design cars, but when the economy skidded in the nineties, he shifted to graphics and ended up teaching product design (“how to make molds”) at the Ceramic Institute in Shigaraki, where he met Momoko and, on the side, learned throwing and glazing clay. By 2008, their house was built and he embarked on a ceramic career. He’s now in his late thirties.

I watch him work in the studio, which has wheels for him and Momoko, as he forms and pokes a bit of clay that will become a tiny strainer inside a teapot. A few feet away, a large machine mixes clay while sucking air from it, then extrudes large, irresistibly smooth noodles of the stuff. The machine is close to the same color as the clay. Tetsuya grins and admits he had it custom-painted to obliterate the standard industrial green. A clue to his fastidious brain.

The pure cup and the pure bowl

Later, we sit at the long kitchen table and look at bowls and cups and teapots and plates and discuss this idea of removing information from one’s work.

“The pure cup,” Tetsuya says, through Momoko’s translating, “and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

“The pure cup and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

One may begin with the form of a traditional Japanese offering bowl. Decorative motifs are removed until it approaches neutrality. Eventually you “come down to the point where we can use it on our table, not for the gods’ offerings.”

Momoko adds: “Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.” He produces smooth dinner plates as blank canvasses for food—altars, really. They’re used in fancy Osaka and Kyoto restaurants to showcase chef art. His works are unsigned, unmarked.

“Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.”

But cultural negation negates a specific culture, and Tetsuya says he has lately realized, when showing his works in China, that they are in some way indelibly, irreducibly Japanese. “I now feel that,” he says, “but I don’t have the answer yet about why I feel that way.”

The potter approaches, but never finds, ideal functionality. Tetsuya tweaks the ancient teacup form a wee bit from batch to batch, always seeking the right feel of cup in hand, the right curve of handle against thumb and finger. This lonely, incremental search for ideal form, endlessly repeated, is itself very Japanese.

The motivation is pleasure, however, not denial. Tetsuya and Momoko are exuberant foodies, and have found that their table-centric philosophy resonates globally through their gorgeous Instagram feeds, @otntty and @otnmmk, with more than 20,000 followers between the two for their pictures of utensils and food.

Tetsuya is also funny. He calls the clay mixing machine Mr. Hiroshira, “my only employee.” What about the beautiful industrial kiln in the next room, I ask? “No,” he says, “I work for it.”

Return to Kyoto

A few nights later, in Kyoto, my wife and I visit a little chocolatier and bakery called Assemblages Kakimoto, near the Imperial Palace. In the minimalist showroom up front I buy a box of orange biscuits enrobed in dark chocolate, each biscuit not much bigger than a postage stamp. Beyond the front space is a narrow, pretty room with a half-dozen seats or so against a counter, facing a tiny kitchen. We order chocolates and cakes and glasses of thirty-year-old palo cortado sherry. Two women to our right—the only other customers in the café—have come for the chef’s omakase dinner. With each course they look gobsmacked, enraptured by the treats placed in front of them. It’s beautiful food, for that is the Kyoto style. Each composition sits on the pale canvass of an Otani plate.

The entanglement of much fuss and no fuss that lies at the heart of many things Japanese is hard to describe, but when I palm one of the Otani pieces that we brought back from Japan, it seems to embody that contradiction. My favorite is a little round vase, the size of a tennis ball, whose satin smooth sides curve up to a sharp-lipped hole that’s big enough to accommodate the stem of a single bud. In weight and delicacy and touch and every other aspect the vase seems, to me, as close to perfect as it can get. It holds a lot of information about Japan. △

Editor's Choice: Journey to Japan

The Beauty of Use

Hidden in the Japan Alps, a Czech-born artist makes woodstoves that match the simplicity of Japanese interiors. Read more »

The Skyward House

Japanese architect Kazuhiko Kishimoto designs a human-scale house for a retired teacher. Read more »

Repair With Gold

The Japanese tradition of wabi-sabi. Read more »

A Platform for Living

A weekend refuge in Japan’s Chichibu mountain range consists of a simple larch wood structure and two North Face tents for bedrooms. Read more »

Zen and the Art of Knife-Making

Using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, a blacksmith in the Japan Alps makes knives so delicate and dangerous they turn chopping into an artful act of passion. Read more »

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. Read more » △

Zen and the Art of Knife-Making

Using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, a blacksmith in the Japan Alps makes knives so delicate and dangerous they turn chopping into an artful act of passion.

A blacksmith in the mountains of Japan uses skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword- making to forge knives from a steel that is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art.

Cutting, slicing, mincing, dicing, boning, peeling: Over time, these mundane jobs have become, for me, the most satisfying tasks in the kitchen. Now, I experience knife-work as a meditation on all that will unfold after food leaves the chopping block. With each cut, I’m trying to shape ingredients to their ideal form, whether it’s a fine mince of onion designed to melt in a pan as a base for a sauce or fifty wedges of apple that need to keep succulence while retaining their shape in an autumn pie. The key to this repetitive-motion, Zenish state is a sublime knife: balanced in the hand, dangerous, delicate, an obedient lover and assassin.

I found my sublime knife after a lot of looking. It has a blade of Aogami Super carbon steel and was hand forged in a mountain town called Niimi, 150 kilometers (93 miles) northeast of Hiroshima, at the shop of a fifty-seven-year-old blacksmith named Shosui Takeda.

My Takeda

If you lay my Takeda 180-millimeter Super Sasanoha Gyutou chef’s knife beside my shiny stainless Shuns and Globals and Henckels, it looks weathered, almost preindustrial. The thin blade has a mottled black finish called kurouchi. The blade tapers sweetly to a gunmetal gray edge whose sharpness approaches that of a razor. You can see the resin used to affix the tang as it was slid into a hole in the Indian rosewood handle during construction. The handle is octagonal, to answer the shape of enfolding fingers and palm. Near the upper rear of the blade’s spine, roughly stamped into the metal, are Japanese characters, plus a heart and the Western letters AS. The characters mean “Niimi. Shosui. Aogami Super.” The heart is something Takeda-san’s blacksmith father started to put on his blades many years ago. Takeda-san says he has never been quite sure what the heart means.

Finding the perfect blade

I have not been to Niimi. I met my Takeda—and, later, two more of them—through Google’s search power and the matchmaking tastes of an American in Tokyo named Jeremy Watson. Watson is a thirty-nine-year-old American of UK and Hong Kong ancestry who moved to Tokyo after a period teaching English in Japan (where he met his wife) and a period learning about, and selling, Japanese knives in Manhattan. In 2012, he founded Chuboknives.com, selling products he found by scouting artisan blacksmiths around Japan. Initially, he hand-wrapped each order, inserting a thank-you note into slim boxes covered in Japa- nese stamps, and sent them on their way to Australia, Europe, and the UK, where chefs and foodies were beginning to notice his trade in rare beauty. Now his business is such that he has automated the shipping. But the boxes remain lovely and intricate, befitting jewelry, and to receive a Takeda in the mail feels like a gift, even if you’ve paid for it.

“We wanted to be a small family business that was connecting small-scale artisans to chefs and home cooks,” Watson says. Big Japanese knife-makers, like Shun and Global, were taking up more and more display space in stores like Williams-Sonoma (where once German companies like Henckels had ruled), but “I realized that the smaller artisans and blacksmiths were really underrepresented. Shibata, Takeda, or Tanaka—the craftsman that we’re currently working with—weren’t really out there.”

The absence of these knives from the major retailers can be explained by the minuscule production of operations such as Takeda Hamono, as the company is called.

Takeda's workshop

“There are three blacksmiths, including me, at the shop,” says Shosui Takeda (whose answers were translated for me by Watson). “We spend eight hours a day forging, twenty-five days a month. In total, we produce 250 knives a month. If we calculate the number of hours all of us work, essentially each person is producing about three knives per day.”

The quality of a handmade knife derives from the strange mutability of steel when it’s repeatedly heated and hammered to alter its molecular structure. The blacksmith, using skills derived from the ancient craft of samurai sword-making, is always chasing an ideal: a blade strong yet somewhat exible, thin but not brittle, able to take an edge and hold it for a long time. A molecular map of a knife would reveal a variety of attributes across its form, determined by cycles of quenching (to harden the steel) and tempering (to selectively soften it). The spine may be softer than the edge. The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it. Takeda has been using AS for twenty-five years, after discovering it in a steel-maker’s catalogue, and after realizing that customers would pay a premium for the uncanny thinness and edge retention that AS offers. “As far as what I’ve seen,” Watson says, “I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as he does.”

“As far as what I’ve seen, I don’t think anyone makes knives as well as [Shosui Takeda] does.”

"The steel that Takeda uses, Aogami Super (AS), is considered the finest base material of the knife-making art, but it’s also known to be temperamental in the forge, and few blacksmiths bother with it."

Watch the YouTube videos of Japanese knife-makers at work: heating steel and iron to narrow temperature tolerances in coal-fired furnaces, then beating away at the metals—using both power hammers and tools wielded by hand—until they begin to fuse and morph like slow-motion Plasticine. The shape of the knife is judged by eye—as is the temperature of the hot steel, judged by the color of its glow in the fire. Heat, hammer, cool, and repeat. Sparks fly. The blades curl out of shape, then return to form under the blacksmith’s art. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding.

"I’ve never seen anything so beautiful and fine that is produced by such fierce whacking and grinding."

That said, Takeda’s approach benefits from modern insights. “I’ve learned a great deal by collaborating with the steel-makers. Through trial and error and using high-resolution microscope photography to see how the steel looks after it’s forged, I’ve been able to eliminate problems with the forging processes.” He quenches his blades in successive baths of hot oil, whose temperature is closely regulated, then sharpens the edge with wheels and stones of increasingly fine grit. His wife and two daughters fix the tangs in the handles at the end, and handle other shop duties.

Dangerous business

The work looks dangerous because it is: “When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves,” Takeda says, “we get burns on our hands and arms every day. This is just part of the job and no big deal.

“What’s more serious are the repetitive strain injuries to my back, shoulder, elbow, and knees. Eight years ago, I had back surgery, and earlier this year, I had surgery on my right knee. I’m currently doing monthly injections so I can keep working. My grip strength is also significantly weaker than it used to be.

“The most serious is the hearing and vision damage. I use earplugs, but I still have hearing damage. Also, constantly looking at the coal-burning oven while forging has damaged my sight.”

"When we’re working in the summer with short sleeves, we get burns on our hands and arms everyday. This is just part of the job and no big deal."

All that pain may explain the paradox of the knife market in Japan. The rise of the global food and chef culture has created unprecedented demand for fine knives, and Watson says artisan shops have more orders than they can fill. The Internet makes new connections between cooks and artisans possible. It would seem to be a perfect time to grow a blacksmith’s business.

“The American solution to this would be to hire more people and build a larger facility,” Watson notes, “but that’s not necessarily the mentality here. A blacksmith team consists of three or four people, and it takes years to train.” Nor are young Japanese lining up for the work. This does not surprise Takeda. He did not intend to be a blacksmith himself; he helped around his father’s shop for bowling money, and didn’t take up the work properly until he was twenty-eight. Were his father not in the trade, he would never have pursued it.

Takeda describes the paradox this way: The knife business is good, the forging business is not.

“During my father’s time,” Takeda says, “there were forty-seven blacksmiths in Niimi—most making agricultural implements [as Takeda’s shop still does]. Now, there are just a handful. The small knife-forging business is literally going extinct. There are very few blacksmiths left.”

Care and maintenance

In my knife drawer are Japanese stones that I use to keep my Takeda knives sharp. The stones, soaked in water, give up a creamy slurry as the carbon steel of the knife is drawn across it. When the knives are done, I use a special little stone to smooth the water stones for the next session. Sharpening is a calming ritual that with a little practice leads to a gleaming thin line of razor sharpness along the gray edge of the blade.

When the knives are sharp, and again after every use, I carefully dry them, because Aogami Super is extremely prone to oxidation. It rusts in minutes. The rust is removed with a light scrub, should I fail to completely dry the knife; this is another little ritual that I enjoy. Takeda is now making an AS line with stainless cladding, which he calls NAS, to prevent rust, but I shall stay old school on further orders as long as he continues to produce them. And there will be further orders, even though his knives run from $120 for a beautiful little paring knife called a “petty” to $380 for an absurdly long, wondrously light Kiritsuke slicing knife that is my favorite cooking tool in the world.

Takeda’s blades have a gentle fifty-fifty bevel, meaning that each side of the blade tapers equally to the cutting edge. This is easier to sharpen for an amateur than the single-side bevels common on many Japanese knives. Beveling and blade shape, like everything else to do with Japanese knives, are complex and relate to the food to be cut: vegetables versus meat versus fish. Some blades are designed for species of fish, others according to what the fish is going to be used for. Everything is about form: of the blade, of the food.

These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief. One gets a glimpse of it at a very good sushi bar, while a multicourse kaiseki meal in Kyoto is like a doctoral dissertation.

"These sublime blades support a Japanese kitchen culture of sublime knife-work, precise almost beyond belief."

Wielding my Takedas, I know that I shall never have such skills. But I do have knives that allow me to meditate on the ideal every day. △

A Platform for Living

A weekend refuge in Japan's Chichibu mountain range consists of a simple larch wood structure and two North Face tents for bedrooms

A collaboration with Dwell.com

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi’s weekend retreat, two and a half hours northwest of Tokyo, is “an arresting concept,” photographer Dean Kaufman says, who documented the singular refuge in the Chichibu mountain range. “It’s finely balanced between rustic camping and feeling like the Farnsworth House.”

“It’s finely balanced between rustic camping and feeling like the Farnsworth House.”

Designed by Shin Ohori of General Design, the structure—Setsumasa bristles at the word “house,” since his desire was for something that “was not a residence”—and its wooded surroundings serve as a testing ground for the Kobayashis, who design outdoor clothing and gear (as well as many other products) for their company, …….Research. The shelter is constructed from locally harvested larch wood and removable fiberplastic walls and is crowned with two yellow dome tents used as year-round bedrooms.

"His desire was for something that 'was not a residence.' "

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi / Photo by Dean Kaufman

Setsumasa and Mami Kobayashi / Photo by Dean Kaufman

Still, this is no primitive lean-to. There’s electricity, hot water, and a kitchen—not to mention iPads, Internet, and a clawfoot tub. By day, the couple trims trees and chops firewood. At night, they sit around a campfire and eat Japanese curry, listen to Phish, and balance their laptops on their knees. This is what a modern back-to-the-land effort looks like.

One North Face tent sits atop a deck; another caps the main building, which contains a kitchen and dining area.

The long, lean Kobayashi complex includes a bathroom and storage room in the structure on the far right.

Setsumasa and Hideaki toss on the rain fly. The solar panel in the foreground supplies daytime electricity.

A stockpile of wood sheltered from the elements.

Setsumasa's desire was for something that “was not a residence”

Scenes from a weekend in the woods feature many .......Research products, including camping cookware and striped wool blankets.

Translucent fiberglass panel walls form a permeable, fiber-reinforced plastic membrane between indoors and out.

Mami and Ishii Hideaki (a friend and .......Research employee) prepare lunch in the cozy main building. The room is rustic and utilitarian, with a double-decker wood-burning stove, tons of open storage, and a sink fashioned from galvanized buckets. But there’s an underlying high-design ethos: The wire baskets are handmade classics from Korbo, a Swedish company, and what looks like a paper-wrapped box in front of the stove is actually a leather cushion by Japanese artist Nakano.

Food is served in traditional camping cookware.

A view of the surrounding tree canopy.

Inside one of the Kobayashis' North Face tents.

The couple stockpiles wood under the deck.

The rooftop tent can be accessed from the interior via a wooden ladder or—for the more athletic—via a series of wall-mounted climbing holds, made by Vock and carved from persimmon-tinted hardwood.

A view of the mountains from the village of Kawakami, en route to the Kobayashis’ property. △

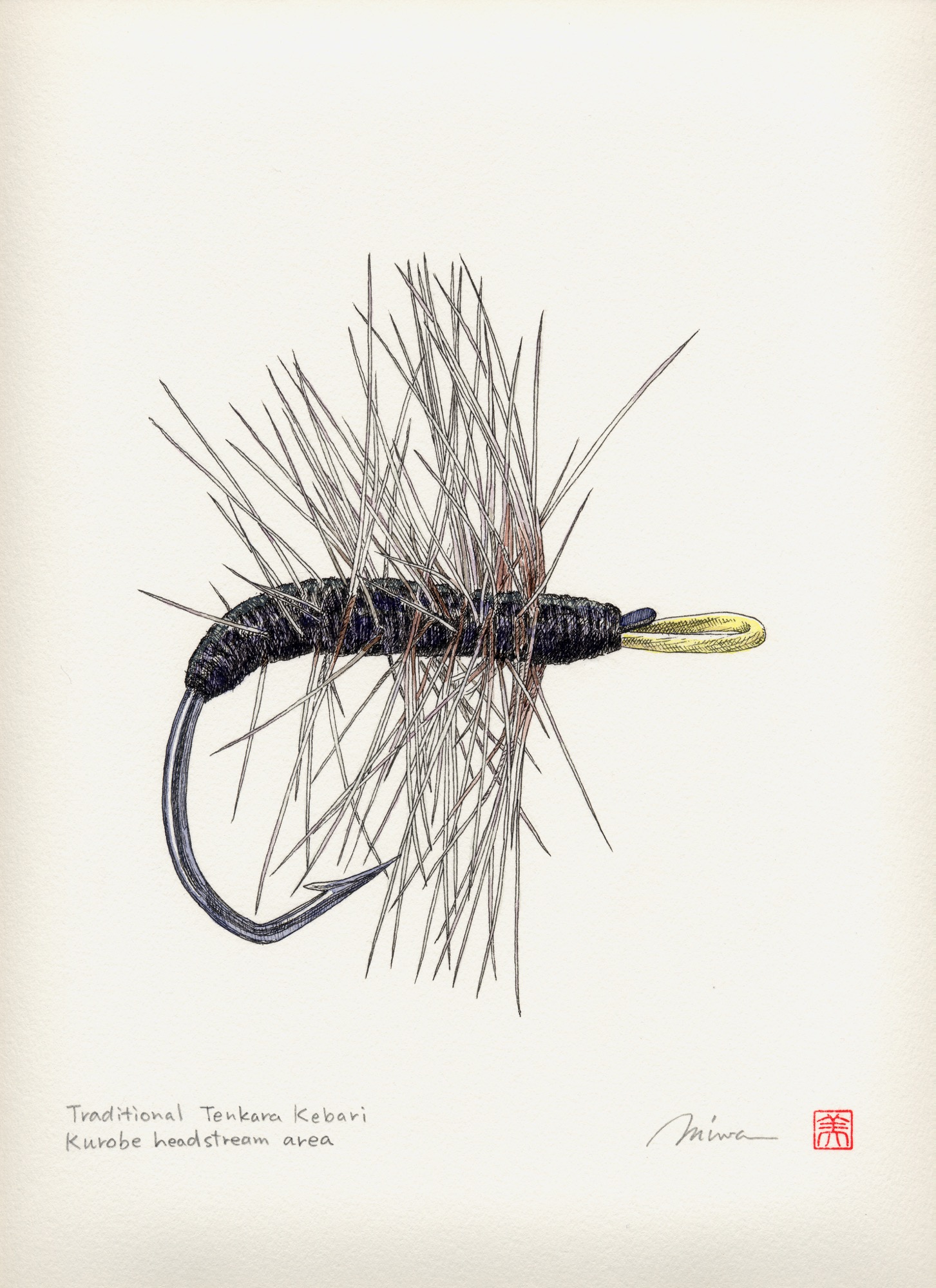

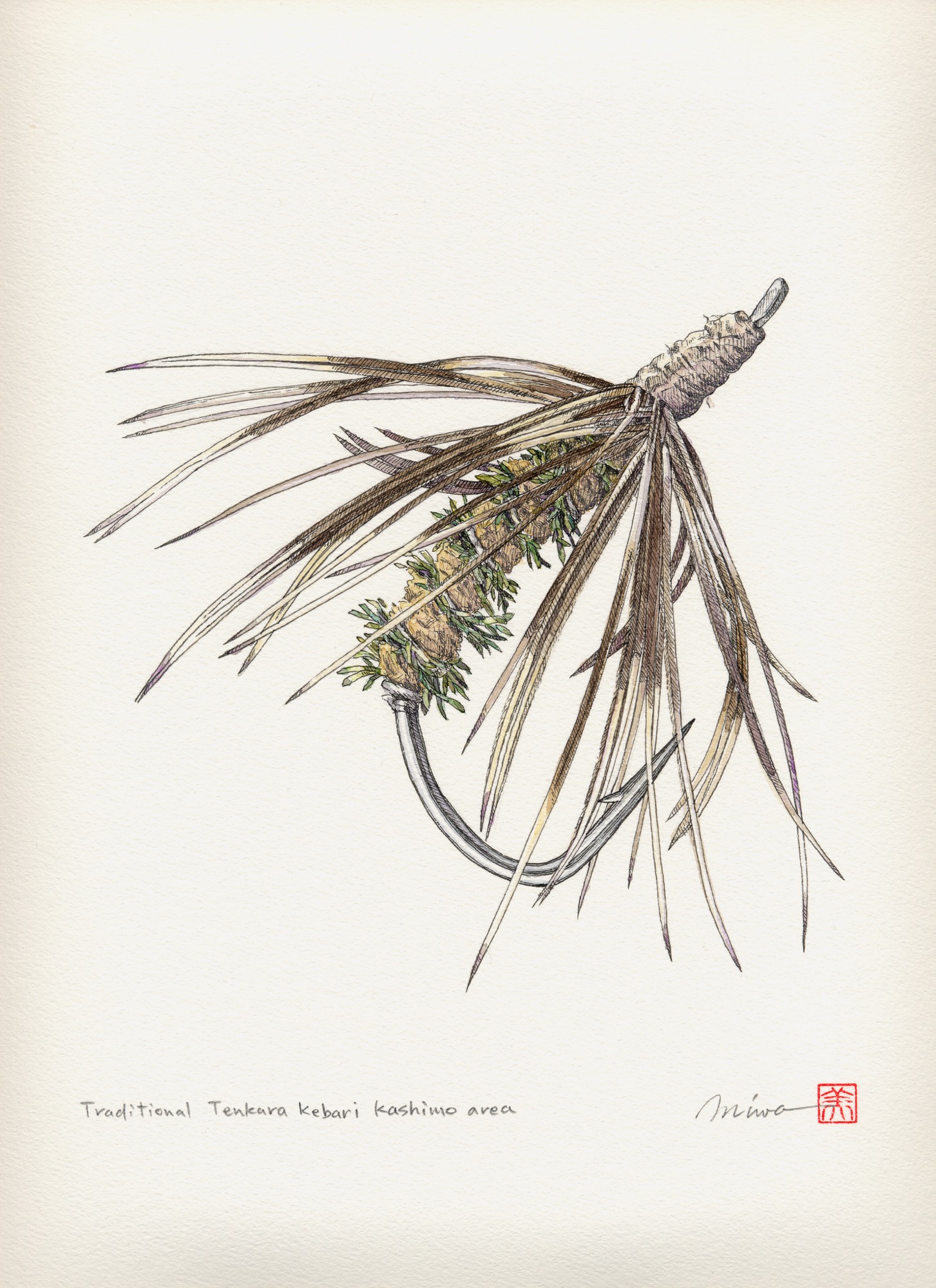

In Search of Tenkara

The founder of Tenkara USA travels to Japan and brings back the traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel

Upon returning from Japan, my mind was filled with the mountain culture of tenkara, a traditional method of fly-fishing with a long rod and without a reel. I had to share my discovery with the people at home. My next journey was founding Tenkara USA.

Clinging to mossy rock with half my body under a waterfall, I watched the torrent crash into a small basin fifty feet below, sending mist into the air and soaking my companions. Mr. Futamura observed apprehensively. Next to him, Mr. Kumazaki preferred to stare at the pool in front of him for any signs of iwana, the wild char found in the mountains of Japan. A fishing rod, small box of flies, and spools of line and tippet were stowed away in my backpack. No reel required.

As tends to happen with shing, we lost track of time somewhere along the way and now faced the crux of the trip. It was seven o’clock in the evening and would soon turn dark inside this lush forest. After a full day of rappelling, swimming through pools in impassable canyons, climbing rocks and waterfalls, and, of course, shing, we were all tired. The route ahead looked straightforward and within my comfort zone, the only caveat being a very wet climb.

My task was to climb to the top, set up an anchor, and belay my partners up. Twenty feet from the top, features on the rock face disappeared on the drier left side and forced me closer to the waterfall, where thick moss oozed like a wet sponge. I was long past the point of no return. I pushed past the fear and focused: hands and feet, hands and feet, hands and feet. The banter between Futamura and Kumazaki suddenly stopped. All sounds, including the roaring of the waterfall, seemed to vanish.

Getting there

My trip to Japan was a journey of discovery. For two months, I stayed in a small mountain village, learning everything I could about the one thing prompting my journey: tenkara.

In reality, I already knew a lot about tenkara. Three years earlier, on my first trip to Japan, I introduced myself to this traditional Japanese method of fly-fishing that uses only a long rod, line, and fly—no reel. After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love. I imagined how great it would be for backpacking and introducing people to fly- fishing in a simple, fun way. There were just so many possibilities.

"After returning home, all I could think about was tenkara. It offered a new way for me to challenge those mountain streams I love."

With little information and no gear available stateside, I took on the task of introducing tenkara to the United States. Over several long months, I created Tenkara USA and since 2009 have been introducing tenkara to anglers outside of Japan. However, despite the knowledge I gained in the last three years, particularly under the tutelage of Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, Japan’s leading authority on tenkara, I knew there was much more. Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers.

"Tenkara is a deceivingly simple form of fly-fishing that holds deep historical, cultural, and technical layers."

History of tenkara

Just as the practice of metalworking appeared independently in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East and among the Incas in South America, evidence suggests that fly-fishing emerged in Europe and Japan independently of one another. Tenkara is similar to the original mechanics of fly-fishing practiced by the likes of Dame Juliana Berners and Charles Cotton, the best-known historical practitioners of fly-fishing in the West. Anglers have practiced similar fixed-line methods in many other parts of Europe, including Spain, France, Italy, and Poland. Yet, unlike the original Western fly-fishing methods, tenkara still lives in Japan.

One main distinction separating tenkara from Western fly-fishing is its origin—tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes. While the West went to work designing fly patterns, weights, strike indicators, and other gadgets to control the reach of a fly or make the activity “easier,” the typical tenkara fishermen of today adhere to the original practitioners’ thrift and reliance on skill. At the risk of seeming irrational to a Western fly angler, most tenkara anglers rely on only one fly pattern, no matter where they fish or what is hatching. As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice.

"Tenkara was an art of necessity for peasants, not a sport for the idle classes."

"As the tenkara philosophy goes, attaining a mastery of skills and technique is more important and efficient than second-guessing fly choice."

Ancient and mysterious origins

Tenkara felt like my own personal Machu Picchu. Here was a rich but hidden mountain culture relatively unknown to the West, so unpublicized that the coastal Japanese themselves only became more aware of it in the second half of the twentieth century. Although researchers can find numerous Western fly-fishing references going back as far as AD 200 or beyond, in Japan, records of the sport only travel back a few generations before disappearing into the forest along with the original, albeit illiterate, practitioners of tenkara.

Even the origin of the name, tenkara, is unknown. The phonetic reading of ten kara could give it the meaning of “from heaven.” However, the name is written in katakana characters, a Japanese syllabary mostly used for words of foreign or unknown origin. This leaves few clues but opens several theories on the original meaning of the word. The most common stems from the way a fly lands from a fish’s perspective, as if it were coming “from heaven.”

Until recently, in most parts of Japan, the method was referred to as kebari tsuri. Kebari means “haired hook” (artificially), and tsuri means “fishing.” In the late 1970s, as the Japanese rediscovered traditions such as tenkara that had flirted with extinction during periods of dramatic economic dislocation, a handful of tenkara enthusiasts began using the term tenkara exclusively to clearly differentiate the practice from other types of fly-fishing. Nowadays, in the appropriate context, it’s used to describe fly-fishing sans reel.

The adventure

I wasted no time getting to the mountains of Gifu prefecture, the region of Japan where tenkara possibly originated. Two friends from Tokyo met me at the airport, we loaded into a rented Nissan and immediately headed for the mountains. The suburbs of Tokyo sprawled endlessly on both ends of the city, a sea of lights with tiny rice paddies in lieu of backyards. Mountains on the horizon appeared impenetrable, abruptly bordering the suburbs as though the country were too small for foothills.

The seven-hour drive southwest was a bridge between two worlds, betraying how a mountain culture could have remained unexplored within a country the size of California. Traveling at sixty miles per hour I imagined how, just a hundred years ago, it would take a full day to cover what I did in ten minutes. I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years.

"I could easily envision how a mountain fishing technique could survive here, unknown to the population centers on the coast and the world beyond, for so many years."

We arrived in Maze, a small mountain village of approximately 1,400 souls in the prefecture of Gifu. Kazuhiro Osaki, who goes by the name Rocky, and his wife, Ikumi, would host me during my stay. For several years, Rocky and his wife have managed the Mazegawa Fishing Center, a tourist center established on the banks of the Maze River to promote angling tourism and other activities in the area. Their home was quaint, my lodging a traditional tatami room with its typical grassy fragrance. A seat at the kitchen table provided a clear view of the mountains to the south. Being the monsoon season, sparse clouds frequently enveloped the mountains. I couldn’t have asked for a more scenic location or for better hosts—it felt like a dream.

Most mornings evolved into a pleasant routine of writing and taking care of the business side of Tenkara USA while drinking a cup of coffee and enjoying the mountain views. In the afternoons I visited the fishing center and tried to uncover the different layers of tenkara through fascinating interviews and encounters with individuals who made (and continue to make) its history. In the evenings, I’d try to fish the yumazume, loosely translated as the “evening activity period,” until it got too dark to see.

A living tradition

Perhaps the mountain culture of tenkara has always been too rich to ever really be at risk of true extinction. Talking to some early Japanese explorers of the tradition, I wonder how close Japan came to losing tenkara.

Eighty-nine-year-old Mr. Ishimaru Shotaro heard about my curiosities through the region’s social network. He came to the fishing center to meet this gaijin (foreigner) who was so interested in his tenkara. He guessed it was 1934 when he began watching a tenkara angler near his hometown of Hagiwara. He explained that approaching a stranger to ask about his techniques simply wasn’t done at the time. Keeping a subtle distance, Shotaro-san followed the angler for an entire summer, periodically going off on his own to try out the techniques he observed. This is how he learned tenkara, then taught others in the area, and is now often referred to as a tenkara meiji, or “tenkara master.” Without any records to prove otherwise, Shotaro-san may have been the rst tenkara teacher in the country.

I asked him why today’s young people think that fishing is difficult—despite the availability of books, magazines, and videos—even though Shotaro-san taught himself the practice simply through observation. He responded simply, “There were a lot more fish back then.” Mr. Shotaro described how at that time, when the damming of the rivers that accompanied Japan’s industrialization was far from complete, he often caught 100 fish a day, with a personal record of 150, numbers common and somehow sustainable among the professional tenkara anglers of the time.

“There were a lot more fish back then.”

When I met him, Shotaro-san couldn’t trust his body the way he did a decade earlier. His legs started giving out three years ago, and since that time, he had not visited the water. Nonetheless, one hour of talking about tenkara was just too much for him to bear. As he had done a hundred times in our conversation, every time he remembered a story about fishing and his youth, he smiled. But this smile was different. I could tell he wanted to fish again. In a very soft voice he turned to his nearby student and said, “Tsuri o shimashoo!”—“Let’s go shing!”

After helping him put on waders, his student and I assisted Mr. Shotaro into the waters of the Maze River. Mr. Shotaro said he wanted to fish with me, since he didn’t know if he’d ever have another chance. With a new vigor, his casting was fluid and precise, the manipulation of the fly enticing. In a stretch of river that had yielded few fish in the two months I was there, Shotaro-san got a fish to rise on his third cast.

Stolen technique

In the early 1960s, the practice of tenkara was as mysterious as it had been in the prewar period. Katsutoshi Amano, a name known to all Japanese tenkara practitioners, had to learn the sport exactly the same way Shotaro-san did before him. As Amano-san said, “Asking a man about his technique just wasn’t done at the time; I had to ‘steal’ the technique from him.” Ironically, given their age difference and the fact that both are from Hagiwara, there is a good chance the man Amano-san followed and mimicked was Shotaro-san himself.

Dr. Hisao Ishigaki, my principal tenkara teacher, and Mr. Amano were instrumental in popularizing tenkara among the Japanese starting in the late 1970s when Japan, at the height of its economic boom, began to rediscover itself and its traditions. In 1985, Japan’s largest TV network produced a segment on the sport, giving people throughout Japan an idea of what tenkara was about. Nowadays, newcomers can look it up online, watch videos, and choose from a collection of books and magazines that offer lessons on knots, flies, and techniques. A once-secretive practice that provided employment to landless peasants is now a source of fascination to urbanized Japanese and a growing number of participants in the United States and other countries.

Tenkara with a twist

Two months went by faster than the glimpse of a rising trout. But I was happy I had found the time to fish a little on a daily basis. My worst fear was that I’d end the journey wasting a lot of time and not “finding tenkara.” I feared my relatively reclusive nature would send me deep into the mountain streams searching for the soul of tenkara anglers from centuries ago, rather than seeking people who are alive and carrying on the tradition.

My fear of wasting time didn’t come true. I enjoyed incredible encounters with old masters, meetings with craftsmen, a very enjoyable time with my hosts and their friends, and a lot of fishing, too. But I also craved adventure.

The same isolation early tenkara fisherman enjoyed was a little more difficult to achieve in modern Japan. So we took to the challenge with canyoneering shoes, neoprene wetsuits, ropes, and harnesses, and our tenkara kit, mixing fishing with what is known as “shower-climbing,” a mix of canyoneering with climbing waterfalls. It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. Our portable gear didn’t add weight to our packs, and the telescopic rods could quickly be stowed away as we prepared to climb a waterfall. By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there.

"It seemed tenkara and shower-climbing were made for each other. ... By conquering wild, pristine, and remote waters, we would earn our right to practice tenkara there."

We set off on an expedition that took us to rugged tenkara-perfect mountain streams, far from the masses that leave many streams ravaged and devoid of fish. Out here, I finally felt the spirit of tenkara fishermen from eras gone by: They disappeared into the forests for weeks at a time, camping and fishing the streams, drying caught fish, and finally, when the catch threatened to be too heavy to carry out, headed back to the village markets.

We planned to build a fire by the river, where we would cook a trout “shioyaki-style”—only sea salt coating the skin, a firm branch serving as a skewer. And we would drink kotsuzake, a drink that, as I have come to appreciate, is underpinned with ceremonial and philosophical significance—though one shouldn’t picture a neat Japanese tea ceremony.

Kotsuzake is primitive and raw. Preparing and drinking it is an act of homage to the principle of not wasting the resources nature provides. After separating the bones from the meat, we placed them over the coals of the re to lightly roast and bring out oils and flavor, then immersed them into the warm sake. The result is sake with subtle and tantalizing fish flavors—all part of the Japanese mountain culture, and now a personal practice if I must eat a trout that I catch.

The cliff-hanger

Back on the treacherous, wet rock face, a small overhanging cluster of bamboo far to the left started to seem more reasonable the longer I clung immobilized by the waterfall. I normally would never trust plants to hold my weight over a fall that could potentially kill me, but at this point, adrenaline dictated my actions. I grabbed a bamboo stalk and slowly shifted the weight off my feet. I placed my trust in a root system that was out of sight under a thin veneer of soil. Through the patch of bamboo and other vines, I finally topped the cliff, beaming in relief. Under heavy rain, I wrapped an anchor rope around an ancient tree lying across the stream. When Futamura-san reached the top, he looked down at the pool below with a nervous smile and said, “Good job; difficult climb.” △

The Beauty of Use

Hidden in the Japan Alps, a Czech-born artist makes woodstoves that match the simplicity ofJapanese interiors.

Secluded in the Japanese Alps, a Czech oven-maker and his Japanese artist wife find creativity in daily life as she weaves rugs from goat hair and he smiths minimalist woodstoves that are as much modern steel sculptures as they are functioning furnaces.

“In November, the mountain puts on her autumn kimono, and it is lovely around a burning stove...”

The first time I saw one of Jirka Wein’s stoves, I was visiting friends in Matsumoto, a city in the valley that stretches along the eastern flank of the Japan Alps a few hours west of Tokyo. It was March, and I had arrived from California braced for the icy floors and bone-chilling drafts typical of Japanese houses built in the traditional style, which is to say without insulation or central heating. Instead, I stepped into a deliciously warm and cozy enclave. There in the entryway sat a fat black stove unlike any I had seen before. Woodstoves are not unusual in heavily forested rural Japan—I had owned one myself when I lived there, as had a number of my more rustic friends—but this one was glossy and sleek, stripped of any frill that might obstruct its absolute simplicity. It looked as much like a sculpture as a functioning furnace. A lively fire flickered against the round glass door, and above that, behind a second door, a pan of pasta baked in a brick-lined oven.

"It looked as much like a sculpture as a functioning furnace."

My friends were quite taken with their stove. It was like a pet, they told me, or a fifth family member with a knack for bringing together visitors and residents alike in toasty communion. Its origin was equally interesting: It came from a remote valley in the mountains south of Matsumoto where Jirka Wein, a seventy-three-year-old Prague-born artist, shaped steel while his wife, Etsuko Seki, wove rugs from goat hair. My friends had driven out to pick up their new acquisition and ended up staying to talk about poetry and pottery and wine—all, of course, while gathered around the inviting flames of a woodstove.

Visiting the oven-maker

I was so intrigued by this story that on returning home I called Wein to ask if I could visit the next time I was in Japan. He agreed, and six months later I found myself sitting beside him as he drove east toward his house from the small train station where I’d arrived. By then it was early November. It had rained the previous night, and as we climbed into the hills, the damp tree trunks stood out like black fault lines against the brilliant foliage. Wein, a grandfatherly man in suspenders and a plaid shirt, seemed as overwhelmed by the beauty of the landscape as I was. “We see the color descending from the top of the mountain, and one day it swallows the place where we are,” he said. His parents had been avid mountaineers, he told me, and the family spent summers in the mountains of Bohemia, instilling in him a lifelong love for alpine wilderness.

A life journey from Bohemia to the Japan Alps

His path from those mountains to these was far from direct. Wein grew up in the suburbs of Prague and studied stage design there before moving to southern France to pursue a master’s degree in art history and archaeology. By the time he graduated in 1973, the political situation in Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia had made returning home impossible. He spent the subsequent decade as a wandering scholar, artist, and spiritual seeker. At a Gandhian ashram in India he learned to spin, and in Santa Cruz, California, he taught weaving. By the early 1980s, he was living at a commune in New Mexico. It was there that he met the itinerant poet and environmentalist Nanao Sakaki, who eventually led him to Japan.

“Nanao was living up in the mountains in an abandoned bear den, writing a play,” Wein recounted as he turned onto a narrower branch of the winding road. “He would come down to the commune to restock. We’d spend all night drinking and singing, and then he would go back up the mountain.” The two became friends and eventually traveled the western United States together, staying with the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. When Sakaki returned to Japan, he wrote to Wein, inviting him to follow. “So I came. It was winter. Then spring came and the mountain was so beautiful I couldn’t believe it,” he said. Thirty years later, he hadn’t left.

At home with Seki

Wein rounded a final curve and pulled up in front of a large old-fashioned house hemmed in by wooded slopes. It was a perfect mild morning, the sky clear, the smell of smoke mixing with the sunlight. From somewhere far below, I could hear an invisible creek rushing past. Wein led me inside a cavernous entryway. The 140-year-old house had belonged to a powerful landowning family, he explained, but by the time he and Seki arrived with their daughter in the mid-1990s, it had been abandoned for decades. A flood had washed away all of the other homes in the hamlet, leaving only monkeys, deer, and wild boar for neighbors. Now, restored, the house was spare and majestic, composed of age-darkened wood and dusty plaster pierced by shafts of light. Gazing out at the wall of trees that pressed in from every window, I asked him if he ever tired of the mountain. “No, never,” he replied, deep smile lines radiating from the corners of his eyes. “I hope it doesn’t get tired of me.”

In the kitchen, Seki, a small, reserved woman in indigo farmer’s pantaloons and a blocky top, was arranging slices of cheese and tomato on top of pizza dough for our lunch. She nodded hello, then carried the pan over to the large stove in the center of the room, opened a side door, and slid it in. Wein donned a pair of black-rimmed glasses and joined her beside the stove.

“You see these two holes on the top?” he asked, pointing to pipes embedded on either side of the chimney. “These suck in warm air from above so that it creates turbulence.” He struck a wooden match and held it above one of the holes; the flame was instantly pulled straight down by the draft. He walked around to the front and told me to look in through the glass window. Behind the crackling flames, I could just glimpse rows of yellow firebricks similar to those used in ceramic kilns. “Wood flames at 600 degrees Celsius. Firebricks accumulate heat, and after they reach 600 it’s hard for things not to burn,” Wein explained. Together with the air system, the brick lining ensures that his striking stoves burn well, which is why they are as popular with his elderly neighbors as they are with design-conscious urban architects.

Wein has been refining this design nearly as long as he has been in Japan. Not long after he accepted Sakaki’s invitation to cross the Pacific, he met Seki, who at the time was weaving rugs in Tokyo (she has exhibited them nationwide). The pair soon moved to a small village not far from their current home. They grew most of their own food and made what they could by hand, learning from their self-sufficient neighbors. “We wove rugs and grew wheat and rye, and when we wanted to make bread, I thought about making a stove,” Wein said.

“We wove rugs and grew wheat and rye, and when we wanted to make bread, I thought about making a stove.”

He found himself fascinated by both the engineering challenges and the aesthetic ones. Older stoves were made of cast-iron parts assembled with screws. Newer ones had heat-resistant sealing materials between the parts and other additions such as catalytic converters that needed periodic maintenance. Wein imagined something completely different. “I wanted to make one without many technical tricks, that was simple, efficient—and for me this is very important—it had to be beautiful and fit well with the simplicity of Japanese interiors,” he said.

“It had to be beautiful and fit well with the simplicity of Japanese interiors.”

His solution was to weld rolled steel into simple forms assembled with the absolute minimum of fixtures (rolled-steel stoves are now available from many companies in Europe and the United States). The steel sheets are made by compressing hot metal between rollers and cooling it in an oil bath, which produces a rust-resistant surface that does not require paint. Since there are no small passages to become blocked by soot, his stoves can burn soft woods such as cedar that are plentiful in Japan. They are also durable and easy to maintain. He patterns their forms on the asymmetries of the natural world, because “if they were perfect circles or rectangles, you would get tired of them.” Each model is named after a plant or animal: peach, wolf, acorn, Japanese plum.

At first Wein did nearly all of the manufacturing himself while continuing to weave alongside Seki. By the early 2000s, however, he was making stoves full time in order to meet demand. Today he splits production between his home and several small family-owned factories in the prefecture: One laser-cuts the steel based on his designs, another rolls it, and a third handles the welding, with his help. The wooden handles come from a craftsman in the Tohoku region of northern Honshu. Wein cuts the firebricks and finishes the stoves himself, at the rate of about one per week, in an open workspace tucked against a lush hillside behind his house. He told me he likes this division of labor.

“When I’m here, I’m like a wild monkey. When I go there [to the welding factory], a bell rings at 10:00 and it’s teatime,” he said, settling into a bench beside the large slab of wood that serves as a kitchen table. Seki opened the door on the side of the stove and pulled out the pizza, releasing a gust of garlic and seared dough into the warm kitchen. She set the pan on the table next to a large bowl of salad greens and sat down across from Wein. As we ate, she talked about her work as a weaver, and I realized that although she is the quieter of the two, her clarity and strength of vision easily match his.

“We make functional things. When people use them, they create the beauty. In Japanese we say yo-no-bi,” she told me. Wein nodded: The expression, which literally means “the beauty of use,” is essential to him as well. It describes the tracks of rust that bloom from scratches on his stoves, the resonance of her earth-toned rugs against the wooden floors, the way their handmade dishes come to life when piled with food.

“We make functional things. When people use them, they create the beauty.”

“Daily life is quite a creative thing,” Seki continued. “Beauty is very important for our heart and spirit, so how we live is important. When I was thirty-nine, I came to live in the mountains. At first I was so shocked. It was too different, and Jirka was quite strict.” He interrupted: “In the beginning I didn’t want to have a fridge, because when you have one you don’t eat fresh things.” Seki continued. “Those ten years made me very strong, and they changed me. After ten years, nature became very close. Lately, Jirka goes to sleep early, and I’m up late. I hear deer crying, and I feel like we belong to the same community of living things in nature. I feel deep joy.”

Lunch had ended, and our conversation was winding down. “Jirka, should we make coffee?” Seki asked. “I’ll grind some,” he replied. They moved together to the kitchen counter, where Wein pulled out a hand grinder. Seki filled a pot with water and placed it on top of the woodstove. Imperceptibly, the beauty of use settled another layer onto its smooth black surface. △

The Skyward House

Japanese architect Kazuhiko Kishimoto designs a human-scale house for a retired teacher

Dwelling in a tiny Tokyo apartment for decades, the school teacher had dreamed of a vegetable and flower garden with a little house—but never of the inspiring minimalist home she eventually built in the woods of her native hamlet. Architect Kazuhiko Kishimoto designed for her a white, womblike core with skylight and outward-focused spaces affording views of her passionately cultivated paradise, plus Mount Fuji and the Japan Alps at a distance. Yoko Fushimi adores her house. It is a small wooden cube set on a slope overlooking a rippling expanse of mountains rising west of Tokyo toward the crescendo of the Japan Alps. The modest exterior belies an unusual and conceptually exciting interior, composed of what architect Kazuhiko Kishimoto calls “inner and outer spaces.” Aside from a skylight at the apex of its peaked ceiling, a pure white, womblike inner space offers few glimpses of the outside world. Conversely, the low, wood-paneled outer spaces focus almost entirely on the surrounding environment. After three years, Fushimi still delights in a house full of interesting contrasts and surprising shapes.

When she first set out to build a house, however, she wanted none of these things—or at least she didn’t know she wanted them. “I never dreamed I’d have a house as wonderful as this. The way the light changes on the white walls, the views at night…I didn’t request any of it,” she said on a recent afternoon. She was sitting in one of the outer spaces, a pentagon-shaped living area dominated by a large window that overlooks the mountains and creates a sense of floating in the sky. A hibiscus plant bloomed vibrantly in one corner. Across from it, on a low sofa, sat Kishimoto; the architect and his client have maintained a cordial relationship since the house was completed.

What she had initially wanted, Fushimi explained, was a garden. She grew up in a large traditional house a five-minute walk from her current home, on the eastern edge of Yamanashi prefecture. The back of the house peered down on a maze of mist-filled valleys, while the front faced a lofty stretch of the Koshu Kaido, one of the five great roads of the Edo period (1603-1868). Many of Fushimi’s neighbors grew vegetables or raised cows to supplement the occasional visit of traveling merchants. Her father, too, would rise early to tend his garden before heading to work at city hall. Mostly he grew flowers, which bloomed in succession throughout the warmer seasons. Fushimi had dreamed about having her own garden ever since. But after high school she had moved away to study education, and then settled in Tokyo, where she remained for forty years, teaching elementary school and living alone in a small apartment.

She dreamed of a garden with a house

As retirement neared, Fushimi decided to return to the hamlet where she had grown up and build herself a house with a garden (or rather, a garden with a house). “The problem was, I didn’t know how to get a house,” she admitted. When she came across an advertisement for a free seminar in downtown Tokyo about “serious home construction,” she decided to attend. Kishimoto was one of the speakers. “It was like love at first sight,” she joked. “I wanted him to design my house. I liked what he had to say.”

“It was like love at first sight. I wanted him to design my house. I liked what he had to say.”

A very human-sized home

“What all my houses have in common is their human scale,” he explained as he sat in Fushimi’s very human-sized home. “The height of the ceilings and the size of the rooms are small and compact, and as a result, the houses themselves are small. But I don’t design individual rooms. I design places that are connected with each other so that you can always sense the whole. They’re very comfortable to be in.”

“What all my houses have in common is their human scale...I design places that are connected with each other so that you can always sense the whole.”

Tiny houses abound in urban Japan, where firms such as Atelier Bow-Wow and Schemata Architects have found mind-bending uses for any chink in the crowded landscape. Most of these, however, are responses to site limitations. Kishimoto was after something different. He wanted to revive a Japanese design tradition that had always made more sense to him than conventional Western architecture, regardless of site size.

“If you enclose a room with walls, no matter how big it is, it feels small,” he said. However, this Westernized approach to home design had become increasingly common in Japan since the 1950s. Kishimoto wanted to do the opposite: make small spaces feel big through creative design. When he set up his own firm in 1998, he turned to traditional architecture for inspiration.

Japanese building tradition — on the mat

Since at least the 1500s, Japanese builders have been using a standardized set of architectural dimensions derived from the size of the human body and the inherent structural limitations of wood. For example, one key unit sets the size of a tatami mat at just under six feet by three feet, around the size of a reclining adult male; as an old proverb points out, all the space you really needs is “one mat when you’re asleep and half a mat when you’re awake.” Three of these mats might make up a tearoom, and five might make a family sleeping area.

The houses comprising these units were often small, but they contained a number of techniques for creating the sensation of spaciousness. “There was a unique way of connecting rooms, a secret hidden in the design,” Kishimoto said. By and large a house constituted a roof, a floor, some posts, and some sliding screens. Spaces were interlinked, solid walls were scant, and inside led fluidly to outside. Kishimoto wanted to translate these concepts of connectivity and human scale into the aesthetic language of modern design.

“There was a unique way of connecting rooms, a secret hidden in the design."

Fushimi hadn’t thought much about architecture until she heard Kishimoto talk about these ideas at the seminar, but what he said appealed to her instinctively. Plus, she liked the look of his houses. After the talk she decided to send him a letter. “I assumed he’d turn down such a small, low-budget project,” she said. Instead he invited her to discuss the project in person, and ultimately took it on.

The design process spanned two years, partly because of the town’s very slow-paced permitting procedure. Kishimoto began by helping Fushimi select a building site from amongst several owned by her family. The lot they settled on had very few technical limitations: there were tree-filled views on all sides, no visible neighbors, and plenty of space. They also discussed her requests. These included wheelchair accessibility so her aging father could visit, a skylight so that light would pour in like it had in a church she once saw on a trip to Europe, and in her words, “three pages crammed with detailed requests, but not a single one that got to the heart of what I wanted.”

Fortunately, this gap between what clients say and the fullness of what they truly want is something Kishimoto devotes considerable thought to in his practice. “Words apply to objects, like the size of the rooms, and any contractor can meet those requests. My role is to respond to the desires people can’t express,” he said. He engages his clients in chitchat, watches their expressions, and replays conversations again and again in his head, trying to grasp what they mean by vague terms such as “beautiful” or “site-appropriate.” “You don’t draw closer to happiness or beauty in a mechanistic way, like climbing a staircase or adding one plus one,” he said.

“Words apply to objects, like the size of the rooms, and any contractor can meet those requests. My role is to respond to the desires people can’t express.”

In Fushimi’s case, Kishimoto thought about how her long years in Tokyo and her request for a churchlike skylight—“a very urban desire”—contrasted with her rural upbringing and her wish to be surrounded by greenery and gardens. Internal contradictions of this sort are common, but how to deal with them? “Modernism wants to clean things up, make them easy to understand. This is city, this is country,” he said. His response was messier: he wanted the visual and spatial contrasts of the house to reflect Fushimi’s own complexity.

A modern take on the little cabin in the woods

What emerged was a very modern take on the little cabin in the woods. The outside of the simple form is clad in unpainted red cedar planks separated by gaps of approximately four-tenths of an inch (one centimeter), which are intended to lighten the building’s visual impact on the landscape. “I thought it would melt into its surroundings as the trees in the garden grew up around it,” Kishimoto said. A wooden ramp leads up the left side of the lot, past a lush garden, and around back to the entryway. The back corner of the house has been sliced off so that the door sits at a diagonal, and the excised space serves as a small porch, now tangled with potted passion-fruit vines and avocado trees.

“I thought it would melt into its surroundings as the trees in the garden grew up around it.”

This wild, leafy space opens onto an entirely different world: the white, light-filled core of the house. Kishimoto intended this inner area to serve as a comforting cocoon where Fushimi could retreat when storms or darkness swept over the mountains. It contains the kitchen, computer area, toilet, and sleeping niche. The walls are white plaster, the floors shiny white ceramic tile, and the custom-made table and kitchen-island are white, as well. Light enters from an opening at the peak of the pyramid-shaped ceiling. Kishimoto encircled this skylight with a steel ring for structural support; the ceiling beams rest on the ring instead of on one another when they converge at the top of the pyramid.

Four “outer spaces” adjoin the inner core. One, reached by hunching through a rectangular opening of Alice-in-Wonderland proportions, is a cube-shaped tea room whose glass outer wall reveals a diagonal line of grass and cherry-blossom trees. Fushimi often uses this room to arrange flowers. Another contains a fragrant pinewood bathtub and a wood-framed window that lets in birdsong and cricket chatter. A tiny porch sits adjacent to the bath. Finally, there is the five-sided sitting area with its sweeping view across the mountains. All four of these outer spaces have much lower ceilings than the inner core, and all are finished in the same cedar panels used on the exterior; the interconnecting lines of the panels strongly accentuate the architectural geometry.

Altogether, inner and outer spaces measure only 640 square feet (ca. 59 square meters). To Fushimi that feels large: she spent decades in a 260-square-foot (ca. 24-square-meter) apartment. She continues to find surprises in her new home. “One splendid thing I recently discovered is that if I stand at the exact midpoint between the kitchen and the bed and sing, my voice echoes so beautifully I sound almost like a professional soprano,” she wrote to me in a letter.

“One splendid thing I recently discovered is that if I stand at the exact midpoint between the kitchen and the bed and sing, my voice echoes so beautifully I sound almost like a professional soprano.”

The most remarkable part of the house, however, is that which Fushimi has created herself. In three years the bare slope of the lot has become a profusion of trees, flowers, and bushes. Kiwi vines, morning glories, honeysuckle, and wild roses twine around moss-covered tree trunks and arbors. Lilies, ferns, and violet sage crowd the pathways. The garden has a wild feeling that is rare in Japan, but perfectly suited to its surroundings (while weeding, Fushimi has spotted foxes, deer, wild boars, monkeys, badgers, and three black bears). She tends to her garden most days that weather permits, and thinks of it as a present to the birds and butterflies and people who wander past. But most of all, it is a long-awaited gift to herself. “Right now,” she said, “I’m completely caught up in playing in the dirt.” △

Repair With Gold

The Japanese tradition of wabi-sabi

The Japanese savoir vivre has a name, yet is almost impossible to define. What does it feel like? Does it live in old objects or is it intangible? Wabi-sabi is the mindful balance between treasuring simply beautiful things and relishing freedom from things. When a piece of pottery breaks in Japan, the traditional practice is to fuse the pieces back together with gold lacquer. The Japanese word for this practice—kintsukuroi—doesn’t just refer to the method of repair, it also suggests that the tea bowl is more beautiful because of the crack. The gold is a bright line of the pottery’s imperfection. In the West, we tend to judge a repair by whether it is noticeable—the less evidence of a rip, scratch, or stain, the better. The traditional Japanese practice is the opposite. In a Japanese tea ceremony, guests are served with the most cracked and different side of the tea bowl facing toward them. The imperfections are emphasized and appreciated.

The sense that imperfection makes the tea bowl more beautiful, or at least more interesting, is known as “wabi-sabi.” Wabi-sabi is very difficult to define. Considered by many to be the aesthetic of Japan, it is a know-it-when-you-see-it kind of thing. And like most aesthetics, wabi-sabi is about more than how things look. It suggests a way to live.

“Things wabi-sabi are appreciated only during direct contact and use; they are never locked away in a museum. Things wabi-sabi have no need for the reassurance of status or the validation of market culture.” — Leonard Koren, author of Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets, and Philosophers

I missed breakfast the morning of my first tea ceremony. Only four months into my stay in Japan, I had not yet adjusted to the Japanese concept of time. When my friend said she’d pick me up at seven, she meant six forty-five: a fifteen-minute sign of respect.

My stomach growled as we drove along the Sai River toward downtown Kanazawa. Japan’s famous cherry blossoms had just reached this small city nestled between the Japanese Alps and the Sea of Japan, on their bloom north from Okinawa to Hokkaido.

To celebrate the season, the small treats, wagashi, served with tea at our ceremony that morning were pink cherry-blossom-flavored macaroonesque pastries. Unfortunately for my empty stomach, we were each given a single, tiny wagashi before our tea was served. Everyone fell silent as they focused fully on eating their treat. A tea ceremony is a cross between performance art and meditation. Each action is intentional and slow; it is a kind of spiritual exercise. The simple act of making and then drinking tea is elevated through total attention to the people and objects involved.

Once we finished our wagashi, an elderly tea master served us ceramic tea bowls full of frothy matcha that required two hands to hold. Splotches of green and black interspersed with faint gold lines covered the surface of each bowl. The rim was uneven, and small nicks lined the bottom. The tea master showed us how to examine our bowl before our first sip. This amounted to a lesson in applied wabi-sabi. We paused to find and create beauty from the simple, humble, and nonobvious—the cracks in our ceramic tea bowls. Cultivating a wabi-sabi mindset requires overriding our default responses to what qualifies as beautiful and what qualifies as ugly, what is worth paying attention to, and what is not. A tea ceremony is one way to practice this, and it is equally important (and useful) in day-to-day life.

Transforming the ordinary

For me, the most important moment of the morning happened once the tea ceremony concluded. We were directed into a drafty back room and told to wait there for lunch. A few minutes later, a teenage boy showed up and placed a stack of seven bento boxes on a table near the door. We passed the boxes around and then began to eat, still wearing the kimonos we had put on for the ceremony, seated atop overturned foam seafood crates.

One of the many sections of the bento box held kaki no ha zushi, a specialty of Kanazawa’s prefecture. Kaki no ha zushi is a square of rice topped with thin slices of fish or vegetables and then wrapped in a persimmon leaf. I eagerly tore open my leaf as I would the paper wrapping of a burger, ready to finally fill my stomach. Seated right beside me was a sixteen-year-old girl named Sui who had taken me under her wing during the ceremony. When one of the tea masters said something my limited Japanese could not decode, she would discreetly slip her iPhone from the sleeve of her kimono and type into a translator. “When you have to stir the tea, more calm”... “Bow before the step back”... I read on a screen the girl shyly turned towards me.

Sui eyed the crumpled leaf of my kaki no ha zushi with concern. Then she reached over, took it from my hands, and folded the leaf neatly around the rice, gently smoothing each corner down with her fingertips so that it matched her own. She handed it back to me, and I felt moved.

Feelings and folding

“It’s a feeling.” That’s as close as I have come to a definition of wabi-sabi from a Japanese person. It came from a thirty-something man named Kei, whom I worked beside as a line cook in a kitchen in Niseko. At the time, I had just been trying to make conversation while we chopped daikon. I didn’t know quite what he meant. “It’s a feeling.”

But months after Kei’s definition, and weeks after the tea ceremony, I kept thinking about Sui’s simple action: folding my leaf. And each time I did, I felt a particular way. I started to understand what Kei meant when he told me that wabi-sabi is a feeling.

It’s the feeling you get when you look at an old kitchen table, not the feeling you get when you look at pristine china in a cabinet. It’s a strange mix of nostalgia for an object’s past and gratitude for its present functionality—and something else, harder to define. It’s the feeling you get when you see a dead flower, or the last traces of a sunset. It is a recognition of the cycles of life and death, use and disuse. It is the feeling you get when you see the natural world reflected in material objects—a rusty patch of metal, a worn piece of wood. Asymmetry is the toll the elements take.

"Asymmetry is the toll the elements take."

Wabi-sabi is looking at the imperfections of the world and transforming them into a kind of beauty—not by changing them, but by changing how we relate to them. Instead of trying to get away from boredom, endings, and loneliness, the feeling of wabi-sabi is what happens when you work to make those things beautiful. It is the philosophical analog of the gold line to emphasize the pottery’s crack.

The leaf that Sui folded for me was nothing if not impermanent—I’d be throwing it away in mere minutes. It was an everyday object—just a little leaf around my lunch. And nothing about our surroundings suggested that the lunch was important—we were in a tiny little room, not even sitting at real tables. But Sui slowed me down, she recognized that the leaf and moment, while imperfect, were still a site of possible beauty. She was not trying to make a point. The ceremony was over. She was just living. And that is what wabi-sabi is: the beauty of the everyday, the small, the inconspicuous. The beauty of life as it is lived.△