Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

Mountain Minimalism—The Next Level

Emerging Boulder artist and graphic designer Adam Sinda contemplates what’s next in Colorado’s art and design scene

Emerging Boulder artist and graphic designer Adam Sinda spends his days working at Made Movement, an ad agency in town. But the Colorado native also loves to paint in his free time and has created original art for two Alpine Modern t-shirts—which he personally modeled for us during a photoshoot set in our own alpine backyard. When he’s not designing or painting, the twenty-four year old loves to get out on the trails and run, alone.

We caught up with Sinda at the Alpine Modern Café to talk about Denver and Boulder’s art and design scene and how Alpine Modern is pushing the envelope on what defines Colorado.

A conversation with trail-running designer Adam Sinda

AM What’s your creative process?

AS Typically, I photograph outdoors; landscapes or anything I am inspired by. Then I bring it back to my room and try to simplify the form as much as possible—and add color. I’ve been working with color, lately.

AM What was your path to becoming a graphic designer?

AS I got a graphic design degree from Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, but I loved to take oil painting classes. That was probably my favorite art class. Design to me is so restricting, sometimes. And walking into an oil painting studio, you can just be yourself and experiment and play and get dirty. Most of my world is making stuff that’s going to be sold, and when I am painting, it’s for me.

AM Meanwhile, you are a graphic designer at Made Movement...

AS Yes, it’s an agency, and we work with brands like Lyft. Typically, we do everything from apps to web banners to illustration.

AM But you also do your own designs, and you have created art for Alpine Modern...

AS When I find a brand I can relate to and I want to be a part of, I jump in, anytime. I really feel Alpine Modern meets my ethics and aesthetics. I was working with photographer Garrett King, and we were just getting out there and going for hikes, just living in the moment.

AM You have designed two t-shirts for Alpine Modern. What makes that medium interesting to you?

AS The fact that other people are going to be wearing it and expressing themselves with it. Though they may never know who made that t-shirt.

AM What inspired those two particular designs?

AS For the Circular tee, what was inspiring me at the time was Alpine Modern’s Instagram. The motif is an abstract pulled from a photograph, and I started sketching and minimizing what I saw, just keeping it clean, simple, modern.

The second tee was the Typography t-shirt. It’s always fun to organize type in a particular way. I traded a mood board with the Alpine Modern team, and that shirt evolved from there.

AM What does it feel like to now see your shirts at the Alpine Modern Shop on Pearl Street?

AS It makes me feel good, happy. Mainly, it makes me feel like I am part of a culture that’s growing right now. A shirt is a simple thing. People build buildings, and people build houses. But sometimes it takes t-shirts and art to make you feel part of a culture. When you’re a developing artist, what you strive for every day is just to be heard, whatever medium it is.

“A shirt is a simple thing. People build buildings, and people build houses. But sometimes it takes t-shirts and art to make you feel part of a culture.”

AM What’s your message you want to be heard?

AS Wherever you are, when you are in a very attractive scenery in the mountains or in a landscape, you’re backpacking somewhere in the woods, take advantage of that moment and remember it because when times get rough, it is nice to pull from those images, and that’s what I would like to say, live in the moment when you feel it’s right. Take a mental photograph.

AM You say your Alpine Modern t-shirts makes you feel you are part of an emerging culture...

AS Right now you can see Denver developing this art culture. But to be honest, I think it is still refining what it wants to be. And Boulder has a huge opportunity to be a part of what downtown Denver is doing right now. And I think Alpine Modern can play into that world and really push the envelope on what Colorado is seen as. It’s cool to see Alpine Modern developing that image right now and really altering what artists are doing today.

AM Describe the Colorado art and design scene for someone from perhaps Berlin or Japan, who has never been here.

AS Art and design here is currently very minimal, very clean, but there are sparks of an identity evolving, and I think we are going to see a shift here. Clean and simple is fun, but what is the next level? What’s after that? Do we start developing some play with color or abstract forms? What’s that next shift? Because if everyone starts doing minimalism in Colorado, you will start seeing it get stale. I think in Colorado in general, we want to create a better culture, we need to spark something a little bit stronger, but I think we are still figuring out what that is.

AM Where will your next spark come from, building on that clean mountain minimalism?

AS Im really inspired by the 3D world right now. It’s fun to take these minimal objects and shapes and use 3D software programs to see behind them and see around them. A lot of designers these days just use Illustrator and very flat design. If you can design and know what’s behind objects, you start to see different light and that’s really interesting to me right now, so I’ve been experimenting with those programs.

AM What is the connection here to being in real landscapes and real nature? Hiking in the mountains is this quintessential three-dimensional experience because you do go behind the trees and behind the mountains and behind the next bend...

AS You’re spot on. When you’re out there with your friends, you’re moving towards an object and you’re reaching a goal. You are achieving something while you are hiking, going from A to B. And it’s fun to see how our designs are going to change with time. We have these VR headsets come out, and it’s gonna be fun to see how 3D plays into Colorado’s art culture. Colorado is such a good place to be right now as a graphic designer and an artist in general, and it’s just going to be even better.

AM What do you do when you are in the mountains?

AS I’m a huge runner. I used to compete in college, in the steeplechase. It has always been my escape. You just put on your running shoes and short shorts and get out the door and run. I love hiking, don’t get me wrong, but there is something cool about just going out and going for a jog by yourself for an hour and then come back and feel refreshed and ready to go. The cool thing about Boulder is you are really never that far away from a really sweet trail.

AM How has your love for the mountains influenced your design work?

AS Greatly. Growing up here and having lived here my whole life, seeing the mountains is comforting. And I think the they say a lot. △

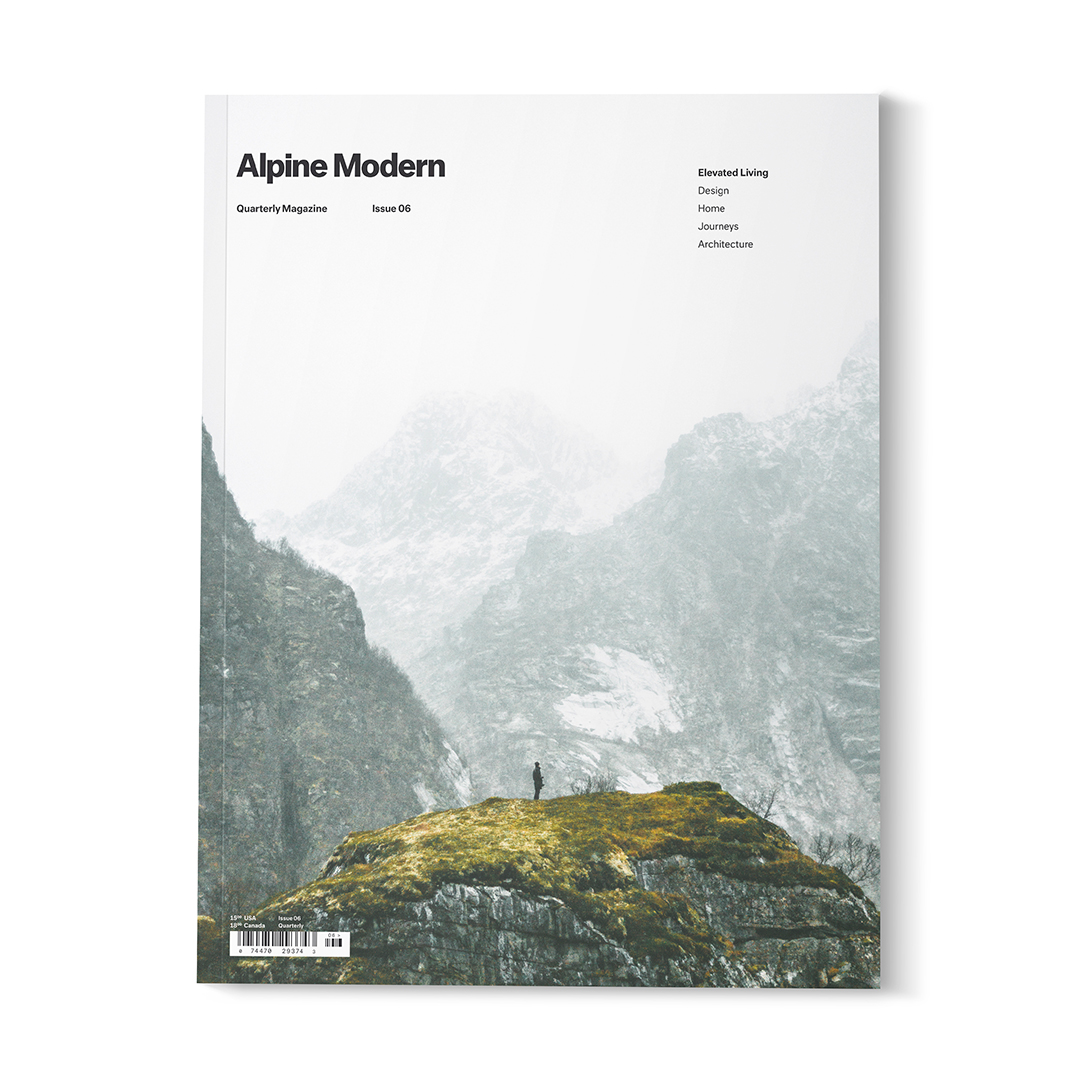

The Nomad Behind the Lens

A conversation with photographer Garrett King, @shortstache on Instagram

Garrett King, a Colorado transplant from Texas, goes by the moniker “@shortstache” on Instagram. The name originates from a company he and a friend started after college, and while the company is no longer a part of King’s life, the tongue-in-cheek name remains and leads 119,000 followers to King’s photography.

King, more comfortable with anonymity than self-promotion or marketing, worked his way from a “weekend warrior” to a full-time photographer and shares his thoughts on the longevity of the field, as well as the community he’s creating through his work in collaboration with others. King’s work emphasizes perspective and playfulness of natural landscapes, while not sacrificing composition and contrast.

A conversation with Garrett King

What got you into photography?

I was born in Amarillo, Texas, and studied design and fine arts at Texas Tech and West Texas A&M. I mainly focused on videography, though, not photography. My friend and I started a company called “Shortstache” where we made short films about people in Texas who inspired us, like the oldest letter-presser in the state and a woman who made bicycles out of recycled materials.

Hence the name: @shortstache?

Right. At the time, we were competing in a mustache-growing contest, and it kind of stuck. Now it’s just me.

And then Instagram came along…

I joined Instagram about two years ago and never had the intention of using it as a platform to turn my photography into my career. I never intended to “make a name” for myself on Instagram. I would just respond back to everyone. They would respond; I would respond. It just kept going.

So it became a platform for community for you?

Exactly. I’ve met some of my best friends in the world through Instagram because we connected over a common goal or interest. I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram. It’s great because you can ask a question about a new place and get feedback almost immediately. Once, a few friends and I went to Portland, Oregon, and I posted that we didn’t have a car but would love to go around the city. Quickly, I got a message from a guy saying that he could be there in an hour, and I’ve been close friends with him ever since.

"I love that I can travel almost anywhere in the world and link up with someone through Instagram."

Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier. I’ve found a mutual respect pervades the community, and it’s been fun to see that come into fruition in my life and work.

"Instagram has this great way of building up trust between people, making the world smaller and traveling much easier."

How did you find yourself transitioning from videography and design to photography?

I’ve spent most of my working life designing. Photography was always an offshoot, a side hobby. It was interesting how things shifted: When I moved to Colorado two years ago, I quickly became a weekend warrior. I was leaving work at 5 p.m. on a Friday, driving until 2 a.m., camping and exploring and shooting wherever I could. I started posting my photos from these trips on Instagram, and, I guess, it sparked people’s interest.

Why camping and natural spaces in particular and not classic city shots or portraits?

I could only do the city thing for so long. You can get nightlife and restaurants in a lot of places, but, when I moved to Colorado, the mountains were in my backyard, and there was just so much to see and do. I found myself always escaping to the mountains to build stories or create memories. I will say, though, some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work.

"Some of the photographers I respect the most are those who can be in the mountains, city, or middle of nowhere and produce beautiful and engaging work."

What has your focus been in developing your work?

For me, it’s always been about storytelling. You could consider me an adventure photographer, but the goal is always about capturing a moment. I want to continually get to the bare essentials and strip things down to the core. When I look at the bigger picture, I hope my work is inspiring and propelling me to see more and do more, while growing as a person. It is an extension of myself, after all. As it gets better, I want to get better. People are always asking me about what gear I use but it’s not really about gear; it’s about a developed style and whether you’re producing consistent and engaging work. I think you have to have the eyes and passion to discover good shots and you have to practice, practice, practice.

"It’s always been about storytelling."

Now that you’re a full time photographer, there must be a necessary separation between Instagram and work for you…

There definitely has to be. Anyone who asks me about their photography and how to make it big on the platform, I try to remind them that it’s a launching pad and business tool. I’ve had companies see my work through Instagram and invite me to shoot for them. It always goes back to the work. Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity. If you’re good and passionate, people will find you.

"Instagram will die at some point, as much as I love it, and you can’t let it make or break your creativity."

Any current projects?

Something I’ve been really excited about is a collaborative effort with other photographers I know, called @collectivenomads. We wanted to take creative people in different mediums and build each other up.

What do you want people to think when they stumble across your photography?

I hope they ultimately see that I’m a real person. Yeah, I want to have a consistent and built-up style, but I want people to see who I am, as a person who does the same stuff as them, and engage.

I never want my work to be dependent on a platform. I’m all about being on Instagram for the right reason: to know people and build relationships. It was never about free gear or “blowing up.” The dream was always to make my lifestyle I love into a paid job. I love design and want to continue to do that while also exploring my work as a photographer. △

Alpine Modern in Its Natural Habitat

Behind the scenes at the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 lookbook photoshoot

We packed up the entire Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Collection and headed up Flagstaff Mountain in Boulder, Colorado.

We stopped halfway up the gorgeous, winding road to the summit. The secluded spot overlooking the city was the perfect place to set up for the shoot. Our good friend Garrett King (@shortstache) behind the lens, and another good friend, talented designer and illustrator Adam Sinda, modeling.

We wanted to capture our Alpine Modern Summer 2016 collection in the most natural and minimal form in which the products were designed and intended to be used. We didn't need a fancy backdrop or expensive studio. We "worked" in Boulder's beautiful backyard.

The goods we design and craft are all about elevating your life. Our mission is to bring modernism to mountain style. From our organic tees and versatile hats to our leather bags coated in an oil finish to repel the elements — our goods are crafted for the mountains but also for daily use and wear. △

More from the Alpine Modern Summer 2016 Lookbook...

In Praise of Walks and Wilderness

To be human in the mountains is to be fragile

Writer and poet Haley Littleton seeks out fragile moments of being that exist in nature—on trails, summits, and cliffs. Climbing mountains and wandering forests, we feel intoxicatingly happy and at once meek in our undefended bodies provoked toward the verge of physical capacity. The alpenglow illuminates the tips of the adjacent ridge as we crest the saddle of the trail. We have settled into our gait and into silence, elongating our steps to reach a lookout point from the gray, shifting scree field. A moun- tain goat follows our path up the rocky steps, and we pause at the top for a breath, a view, and water. This is a moment when I feel extraordinary happiness. It doesn't matter that in our ascent of Mount Sherman, we missed the peak three times, ascending three different 13,000-foot (ca. 3962-meter) peaks instead, or that our planned three-hour hike turned into six hours. I was content to crouch down and stare at the mauve and olive-colored succulent plants that lined the ascent to the peak and wonder what species they were. I was not concerned when or how we would reach the eventual summit.

When critic and poet Charles Olson spoke of poetry, he spoke of walking and of breathing. He spoke of measuring the line of the poem to the rhythm of breath. This “projective verse” called the whole body of the poet into measure. This is a form of “frolic architecture,” as Olson calls it, which one might consider artful kinesiology: to trace out lyric and language with body and space and mountain. By being a participant in nature, one is able to listen and then create from this space. We’ve all had those moments when we step out into the fresh mountain air: breathe in, breathe out, recenter.

It’s like Moab this past March: While back home was filled with uncertainties, rifts, and unpleasant memories, to stand upon the plateau and look across at the deep tannish reds, browns, and yellowish greens of Upheaval Dome—cuts made thousands of years ago—even in the sweltering heat and the sweat of the hike, I felt a peace I have not found elsewhere. I stood and thought of Edward Abbey’s words in the preface of his book Desert Solitaire:

Benedicto: May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end, meandering through pastoral valleys tinkling with bells, past temples and castles and poets’ towers into a dark primeval forest where tigers belch and monkeys howl, through miasmal and mysterious swamps and down into a desert of red rock, blue mesas, domes and pinnacles and grottos of endless stone, and down again into a deep vast ancient unknown chasm where bars of sunlight blaze on profiled cliffs, where deer walk across the white sand beaches, where storms come and go as lightning clangs upon the high crags, where something strange and more beautiful and more full of wonder than your deepest dreams waits for you beyond that next turning of the canyon walls.

More full of wonder than your deepest dreams, indeed. I kept looking over to my friend, continually proclaiming: “I can’t believe how happy I am here.” I understood Abbey’s fierce ecological devotion to the place. Preservation begins with appreciation; it begins with experiential love. “Earn your turns,” a friend always calls out, strapping his skins to his skis and hoisting his body up the incline. Another pal takes off to the mountains when big life decisions loom in front of him: “It’s the only place quiet and still enough to think.” One hikes fourteeners to prove to himself that his body is capable of more than he believes and that what others say about him is not the whole story. One of my best friends may have hated the peak I dragged her up during our climb, but afterward she turned to me and sighed, “I’ve never felt more alive or more in love with my body.” Once, on a backpacking trip with high school senior girls, one turned excitedly to me and said, “I haven’t thought badly about my body this whole trip!” I think of my skis hanging over the ledge of Blue Sky Basin, my toes hurting like hell, my legs are tingling and frozen, and my flight-or-fight mode tells me that the drop in isn’t worth the potential outcome of pain. But when I look up at the snow-crested ridges against the deepest blue backdrop I’ve ever seen, I push on and fire up my legs, reminding myself that this view is worth the discomfort it takes to reach it.

In an age that saw the rise of print reproduction, philosopher Walter Benjamin spoke of original art as containing an “aura” that reflects its presence in time and space: the sentiment contained within and the value connected to an experience with art. It's a sense that mirrors the way we sometimes want to touch a piece of artwork on the walls to simply feel it, as if to be a part of it. This same aura exists in nature: “If, while resting on a summer afternoon, you follow with your eyes a mountain range on the horizon or a branch which casts its shadow over you, you experience the aura of those mountains, of that branch,” says Benjamin. Sculptor Andrew Goldsworthy embodies this idea of “nature aura” in his entirely nature-derived pieces made from branches carefully arranged, leaves woven together, stacks of rocks or ice melted and refashioned, all of which rest entirely upon impermanence. Happen upon his works before they are gone.

If human sense perception changes with historical circumstance, what does the recent technological boom and rise of virtual realities do to our perception of nature? Why does climbing a mountain matter if we can see the same view on Instagram? Why does visiting a location matter if Google Earth offers us the same view from the sofa? It seems this sense of feeling is disappearing as the search for experience is constantly digitized and commercialized. We pry a thing from its shell and market the hell out of it. We want things to be more accessible, to be easy to get to, so we pave roads on the tops of fourteeners and take all risk out of our outdoor adventures. Or, we consistently see pictures on social media of beautiful scenes and stay content to remain inside. But there’s something about the body that matters. There’s something about being there that we miss.

Ecologists speak now of a need for “deep ecology,” not just an understanding of ecological issues and piecemeal scientific responses, but an overhaul of our philosophical understanding of nature. Instead of viewing mankind as the overlord of nature, it’s about revisiting the idea that a give-and-take relationship exists between the human and the nonhuman, a relationship that thrives on mutual respect and appreciation. To develop this sort of appreciation for nature and the nonhuman, it matters that we actually experience it. For many ecological thinkers, walking among mountains can be the first step in healing a false split between body and mind. The grief at the destruction of a beautiful building, the ecstatic joy of a sunrise in the mountains—these moments stem from this unification of the two.

“For many ecological thinkers, walking among mountains can be the first step in healing a false split between body and mind.”

Fragile moments of being that exist in nature

It’s a question of place versus nonplace. In The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities, Richard Sennett points to the peculiarity of the American sense of place: “that you are nowhere when you are alone with yourself.” Sennett speaks of cities as nonplaces, in which the person among the crowd slips into oblivion, only existing inside him- or herself. Other nonplaces look like the drudgery of terminals or waiting lines or places where all eyes are glued to phones. The buildings are uniform, and the faces blur together to create a boring conglomerate of civilization. If to be alone in a city is to be nowhere, the antithesis must be that to be alone in nature is to be everywhere. Nature is a place characterized by its “thisness,” as Gerard Manley Hopkins describes it—a place to enter into that is palpable with its own essence and feeling.

But as we lose our connection to place, as virtual reality turns here into nowhere, we lose our ability to narrate our experiences of nature. Recently, nature writer Robert Macfarlane pointed out that in the Oxford Junior Dictionary, the virtual and indoor are replacing the outdoor and natural, making them blasé. When we lose the language to describe our connection to landscape and place, we lose the actual connection to these things and the value decreases, separating us from the natural. According to Macfarlane, we have always been “name-callers, christeners,” always seeking language that registers the dramas of landscape, and the environmental movement must begin with a reawakening of natural wonder–inspired language.

Perhaps the point of all of this is to work to develop more refined attention, an ability to seek out and perceive fragile moments of being that exist in nature. We must pay attention to our breath and our bodies. Wendell Berry, a prophet of the natural, writes that to pay attention is to “stretch toward” a subject in aspiration, to come into its presence. To pay attention to mountains, we must come beneath them and reach out toward them.

To walk is to perceive

How do we begin? By wandering within the wilderness. Rebecca Solnit’s book on walking comes to mind: “Walking is one way of maintaining a bulwark against this erosion of the mind, the body, the landscape, and the city, and every walker is a guard on patrol to protect the ineffable.” While people today live in disconnected interiors, on foot in wilderness the whole world is connected to the individual. This form of investing in a place gives back; memories become seeded into places, giving them meaning and associations both in the body and the mind. Walking may take much longer, but this slowing down opens one up to new details, new possibilities.

Brian Teare is one of my favorite modern poets because his poetry is centered upon Charles Olson’s projective verse and on walking. All his works contain physical coordinates, anchoring each work of art to the place that inspired it. The land becomes the location, subject, and meaning to the thoughts and feelings that Teare wants to convey. As we enter into a field or crest the ridge of a mountain, we perceive the sight of the landscape and experience our bodies within it. We feel the wind and touch the dirt; we see the edges and diversity of the landscape. Perhaps we have hiked a far distance to reach this place and feel the journey within the body. Teare says in one of my favorite poems, “Atlas Peak”:

we have to hold it instead

in our heads & hands

which would seem impossible

except for how we remember

the trail in our feet, calves,

& thighs, our lungs’ thrust

upward; our eyes, which scan

trailside bracken for flowers;

& our minds, which recall

their names as best they can

Sitting on the side of Mount Massive, on the verge of tears, I felt utterly defeated. Our group took the shorter route, which had resulted in thousands of feet of incline in just a few miles, and my lungs, riddled with occasional asthma, were rejecting the task before them. It felt as if all the rocks in the boulder field had been placed upon my chest. My mind went to the thought of wilderness: Was it freedom or a curse? What would happen to me if something went wrong up here? Risk and freedom hold hands with each other in the mountains. After a long break, a few puffs of albuterol, water, and grit, I pulled myself up the final ascent and false summits along the ridge. I have been most thankful for my body when I have realized how beautifully fragile and simultaneously capable it is. On the summit, as we watched thin wispy waves of clouds weave into each other and rise around us, the mountain gently reminded me that I am not in control. I am not all-powerful, and nature’s lesson to me that morning was to respect its wildness.

"Risk and freedom hold hands with each other in the mountains."

As in all things, essentialism should be avoided. We live in a world that tends toward black-and-white perspectives, and when one praises the wilderness, those remarks can devolve into Luddite sentiments that are antipeople, antitechnological, and antihistorical. This solves nothing. Advancements in civilization are welcome and beautiful; technology has connected us in unprecedented ways. But as with anything, balance is key. We need the possibility of escape from civilization, even if we never indulge it. We need it to exist as an antithesis to the stresses of modern society. We need wilderness to serve as a place to realize that we exist in a tenuous balance with the world around us. All the political and societal struggles matter little if we have no environment to live in. In a world of utilitarian decision-making, a walk in the woods may be considered frivolous and useless, but it is necessary. The choice to preserve or to dominate is ours. But before deciding, perhaps one should first wander among the mountains. △

This essay is accompanied by the poem "Post Tenebras Lux" by Haley Littleton.