Inspirations

Explore the elevated life in the mountains. This content debuted in 2015 with Alpine Modern’s printed quarterly magazine project.

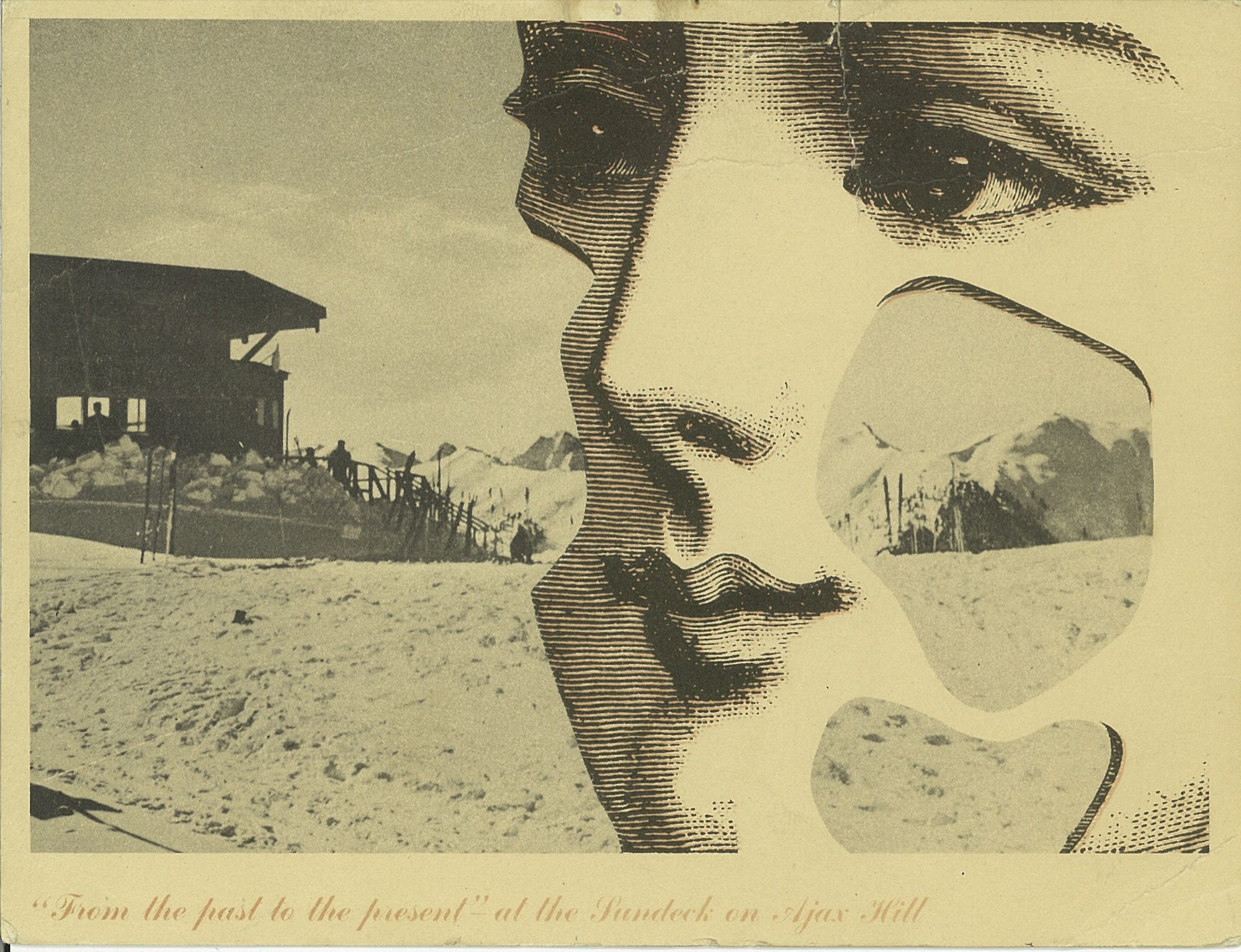

How American Modernism Came to the Mountains

A daughter of America's midcentury-modern movement remembers how Chicago’s design elite settled in Aspen, giving rise to modernism in the mountains of the West.

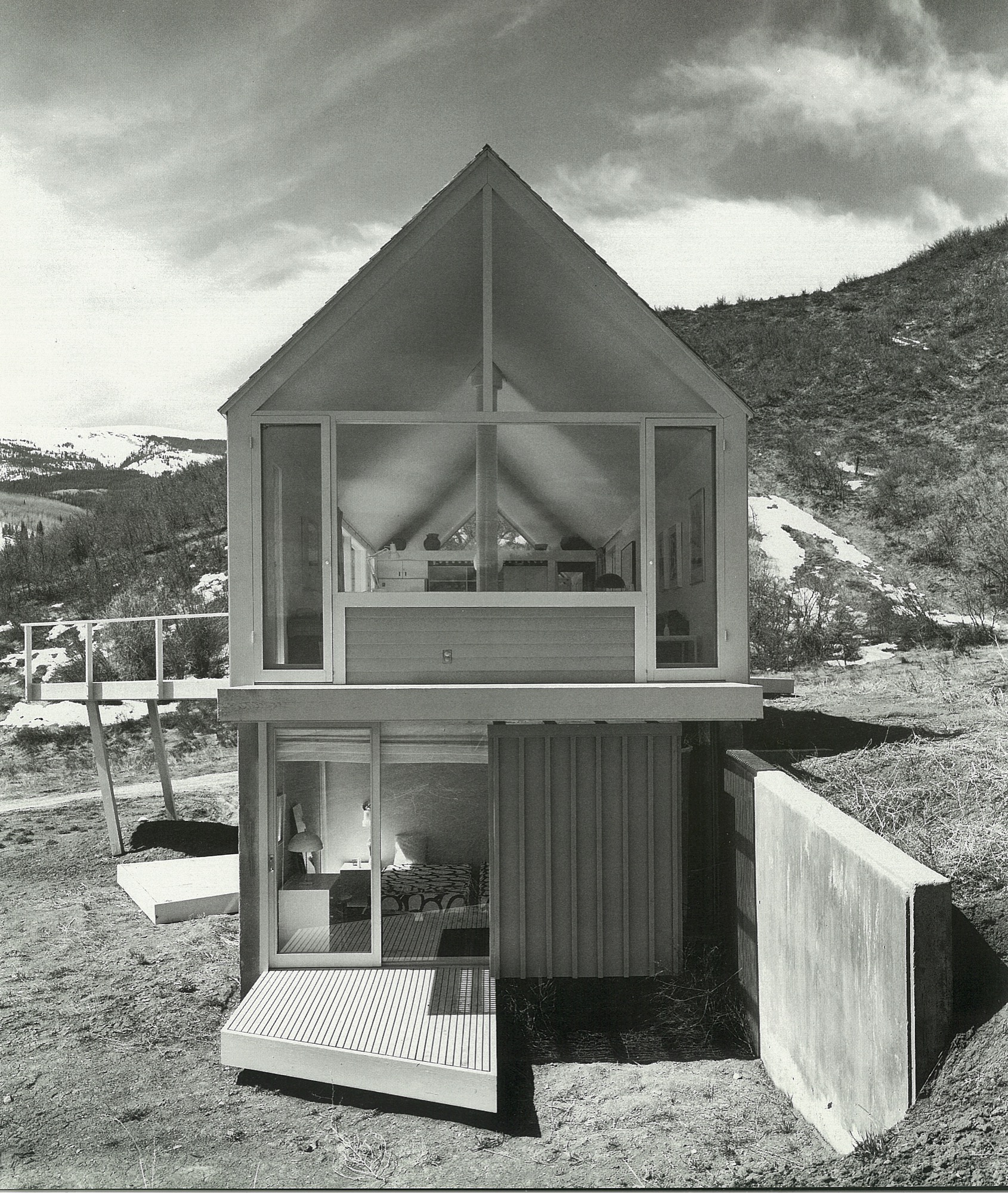

After World War II, Chicago’s design elite flocked to Aspen for ski and summer holidays, galvanizing the then-sleepy alpine village with modern mountain chalets and avant-garde public buildings that helped transform Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley into the glamorous destination it is today. A memoir by artist Marcia Weese, daughter of Harry Weese, a central figure in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern.

Someone recently remarked to me that I was “born to design.” Over the years, I have come to appreciate this birthright, as I realize I have tenaciously and (mostly) joyously cleaved to the creative life, and still do. I have my parents, Harry Mohr Weese and Kitty Baldwin Weese, to thank for this. The creative life is not for the faint of heart, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Childhood in Chicago

It was the early 1950s in Chicago. As my mother told it,

“The war was over. No one had any money. No one had any furniture. Apartments to rent were scarce. We made do.”

When I was very young, we lived in a dim railroad flat in downtown Chicago. This was a typical inner-city apartment with a linear floor plan. The only natural light filtered through windows in the front and back. Chicago was a coal-burning city, and you could write your name on the window sills in the soot. I remember running down the dark hall that connected front to back, with crayon in hand. My parents encouraged my sisters and me to draw on the walls in that nondescript hall. What a great idea they had to spruce up the crepuscular gloom of the hallway, and how fun it was for us to break the rules.

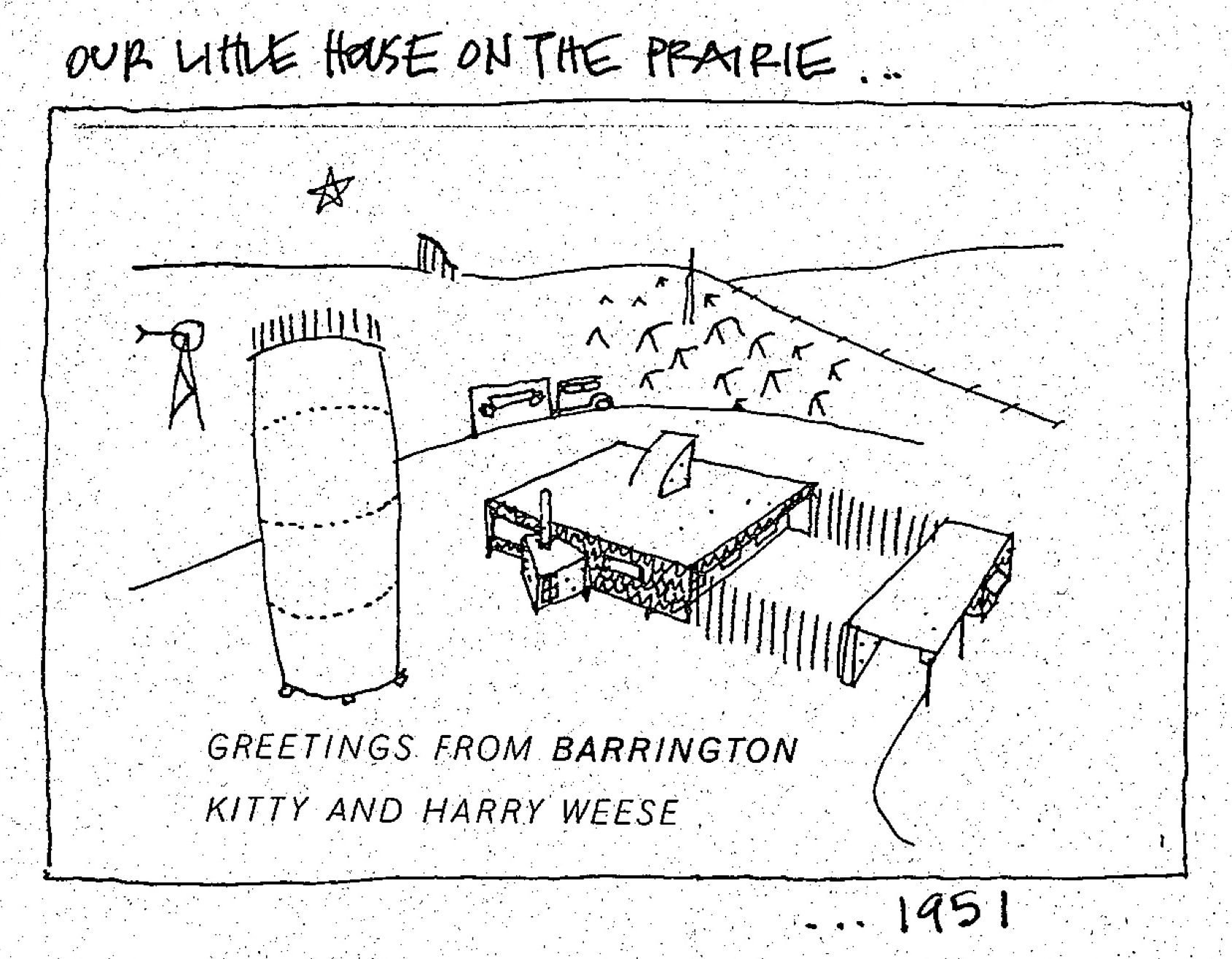

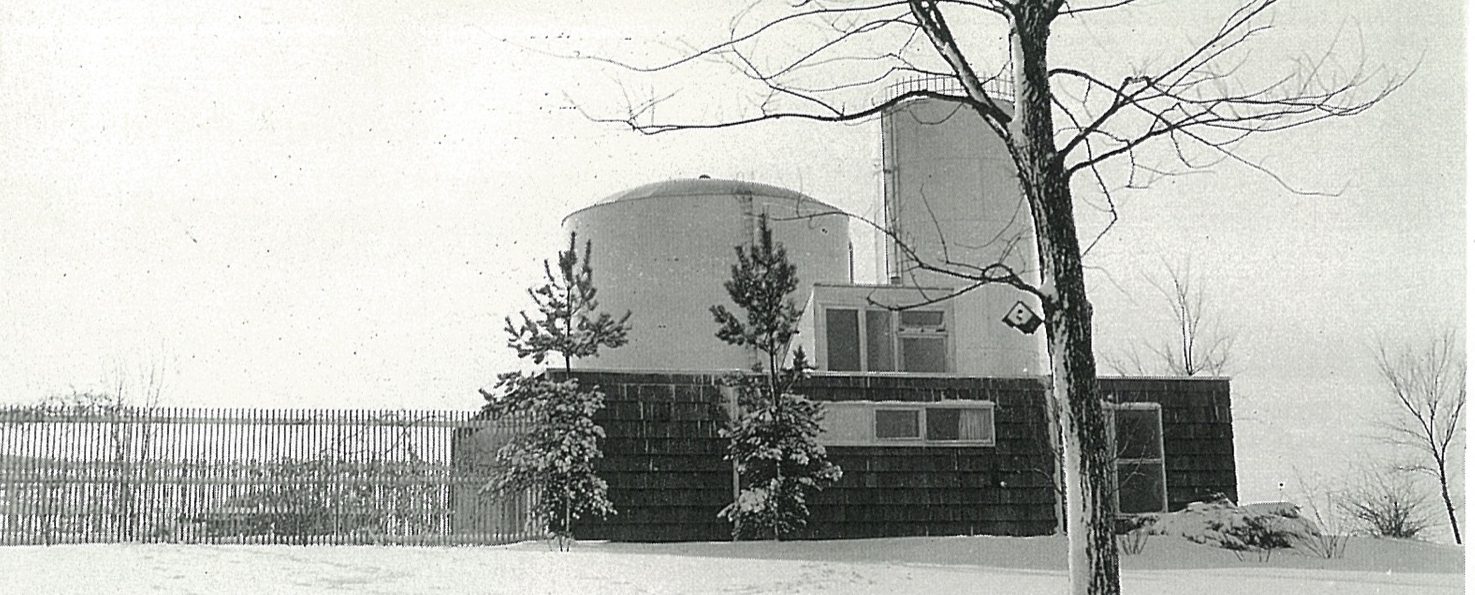

We spent weekends and summers in the country forty miles northeast of Chicago. Now it is wall-to-wall suburbia, but back then, we bundled our five-person family, one cat, two turtles, and several guinea pigs into the car and drove (pre-Kennedy expressway) through many stoplights to the little town of Barrington, Illinois. There, we lived in one of my architect father’s early houses. Built on a lot adjacent to two immense water towers belonging to the town, the house was modern and modest; a one-story house with a flat roof, carport, gravel driveway and a fenced-in garden the three bedrooms emptied into. It was sparsely furnished, and I will always remember the black-and-white linoleum floor. Mom found some dinner-plate-sized checkers pieces and we played checkers on that floor to our endless delight.

Some years later, my grandfather gave my father a nearby five-acre (two-hectare) plot of land, which consisted of a hill, many large oak and hickory trees, poison ivy everywhere, and a hand-dug lake topped off with a pet alligator. Here, my father built a wonderful and quirky house (prebuilding code) he named “The Studio.” We spent many years toggling between city and country. This was a refuge from the city for my parents, and for me, a secret garden of woodland flora and fauna.

Studying with the Eamses & Co.

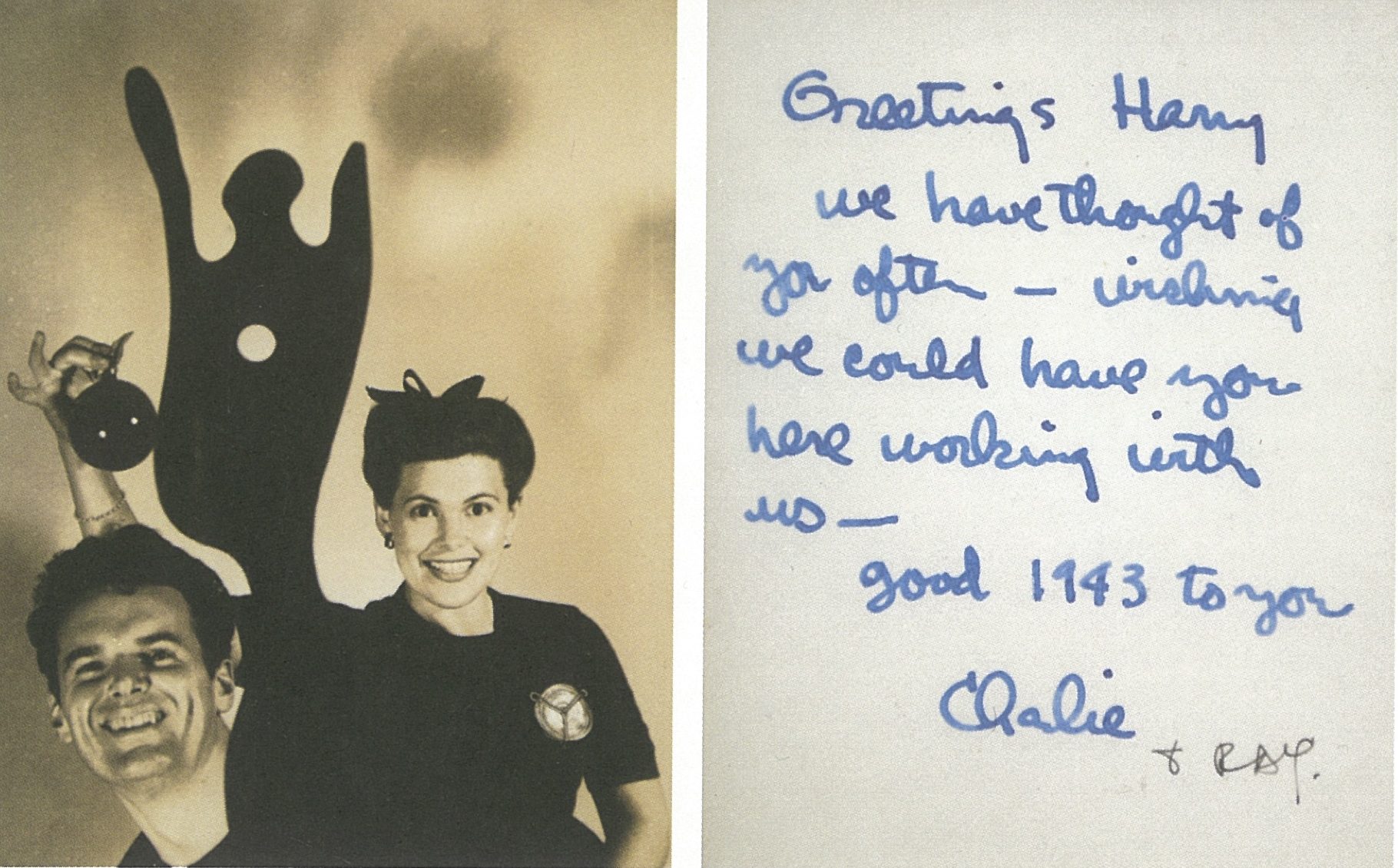

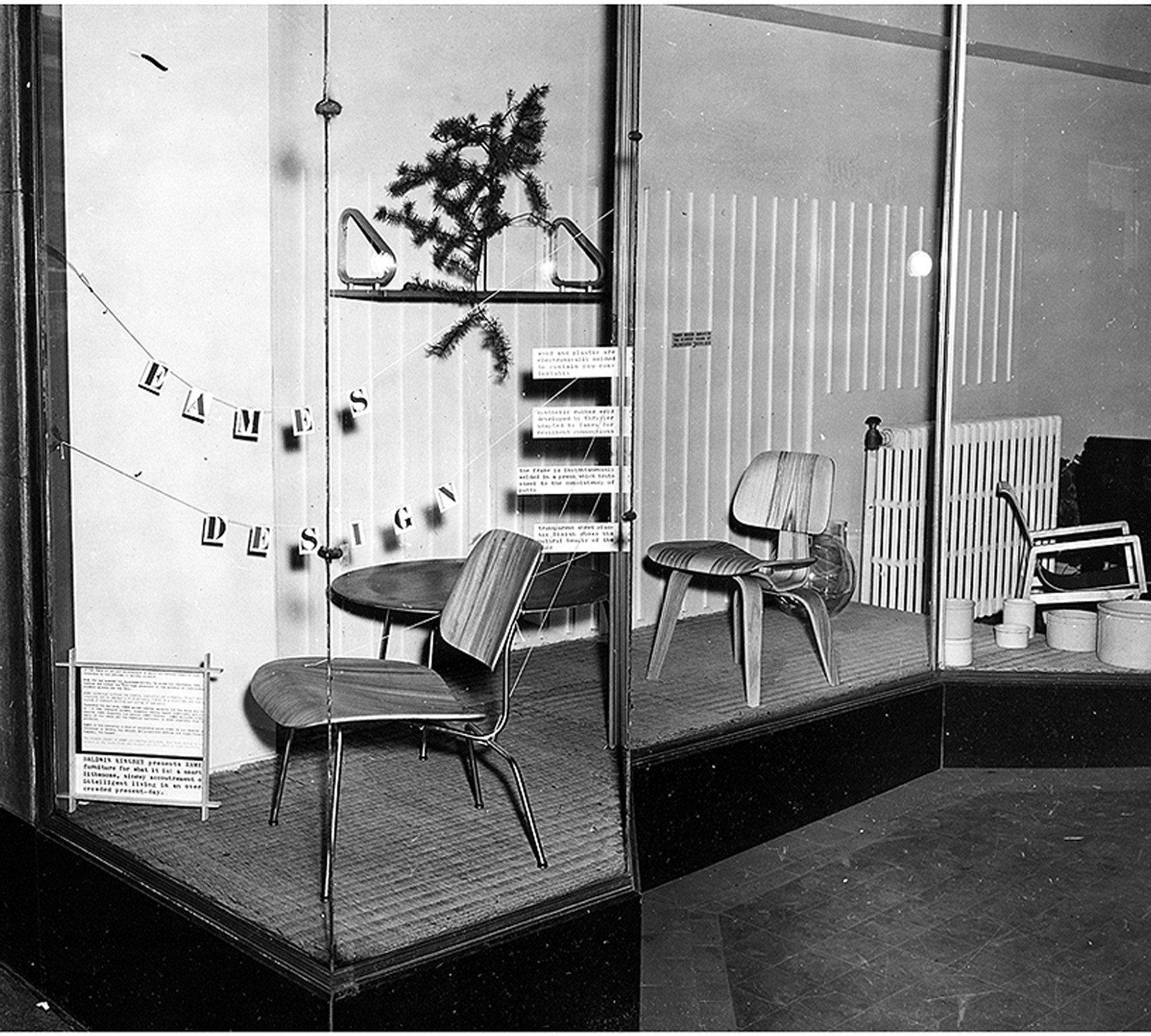

After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in architecture and engineering, Dad studied in Michigan at the Cranbrook Academy of Art with Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ben Baldwin, and a host of others who were living and creating modern design at a time when the atmosphere was ripe for it.

As history has revealed, many became household names, even demigods, in the movement we now refer to as mid-century modern. These people were some of my parents’ closest friends.

My father and Ben Baldwin had won a few industrial design awards from the Museum of Modern Art while at Cranbrook, so they decided after graduation to “hang a shingle”—Baldwin Weese—to practice architecture in New York City. They worked together for a year but decided to convivially go their separate ways; Ben stayed in New York, and Dad returned to his birthplace, Chicago. But first, Ben introduced my father to his sister Kitty.

When Harry met Kitty

As my father approached the house to meet Kitty for the first time, she watched him jump over the fence rather than use the gate. That did it for her. He was a nonconformist, an inventor, a man who loved to use the path less traveled. He had no use for convention as it was, in the post WWII era. The overriding spirit was “rebuild,” therefore “build anew.” This was the perfect time for him to launch his architectural career in Chicago. He founded the architecture firm Harry Weese & Associates, which lasted for fifty illustrious years. My mother, who was southern, elegant, and graceful, was over the moon for this artistic, restless spirit. Not a typical match, but it worked; he needed her organized calm and “good eye for design” to manage his ambitions.

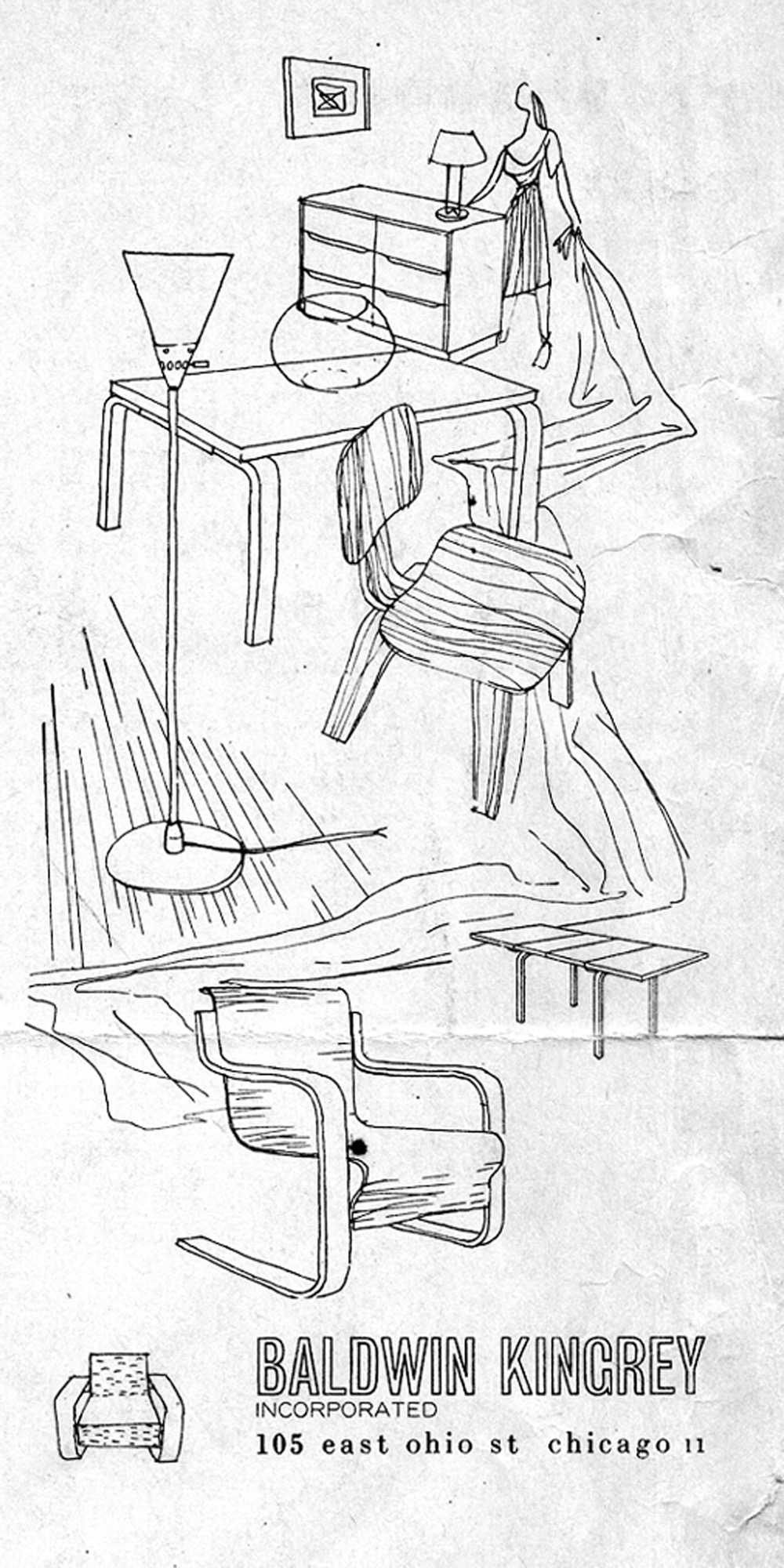

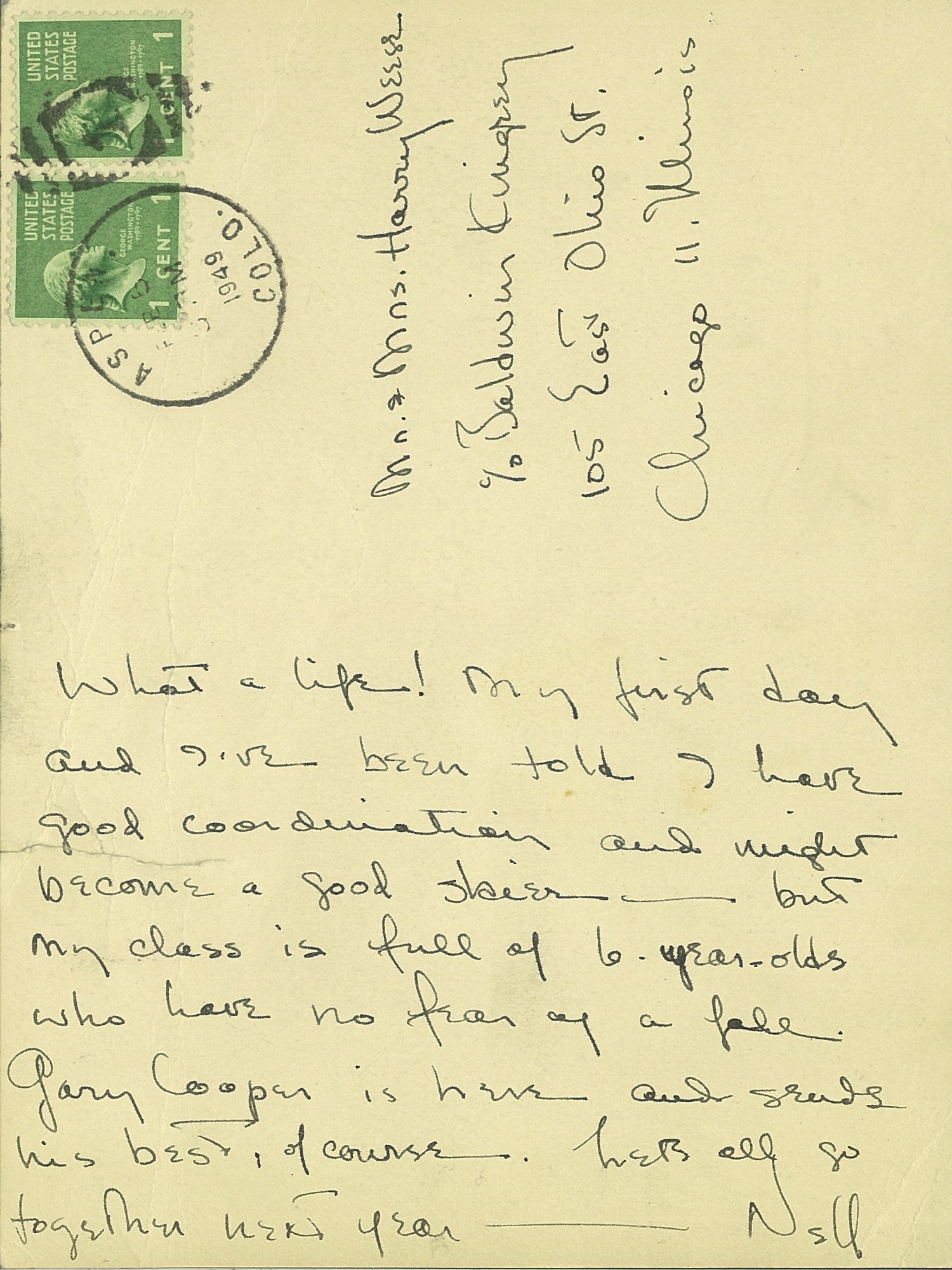

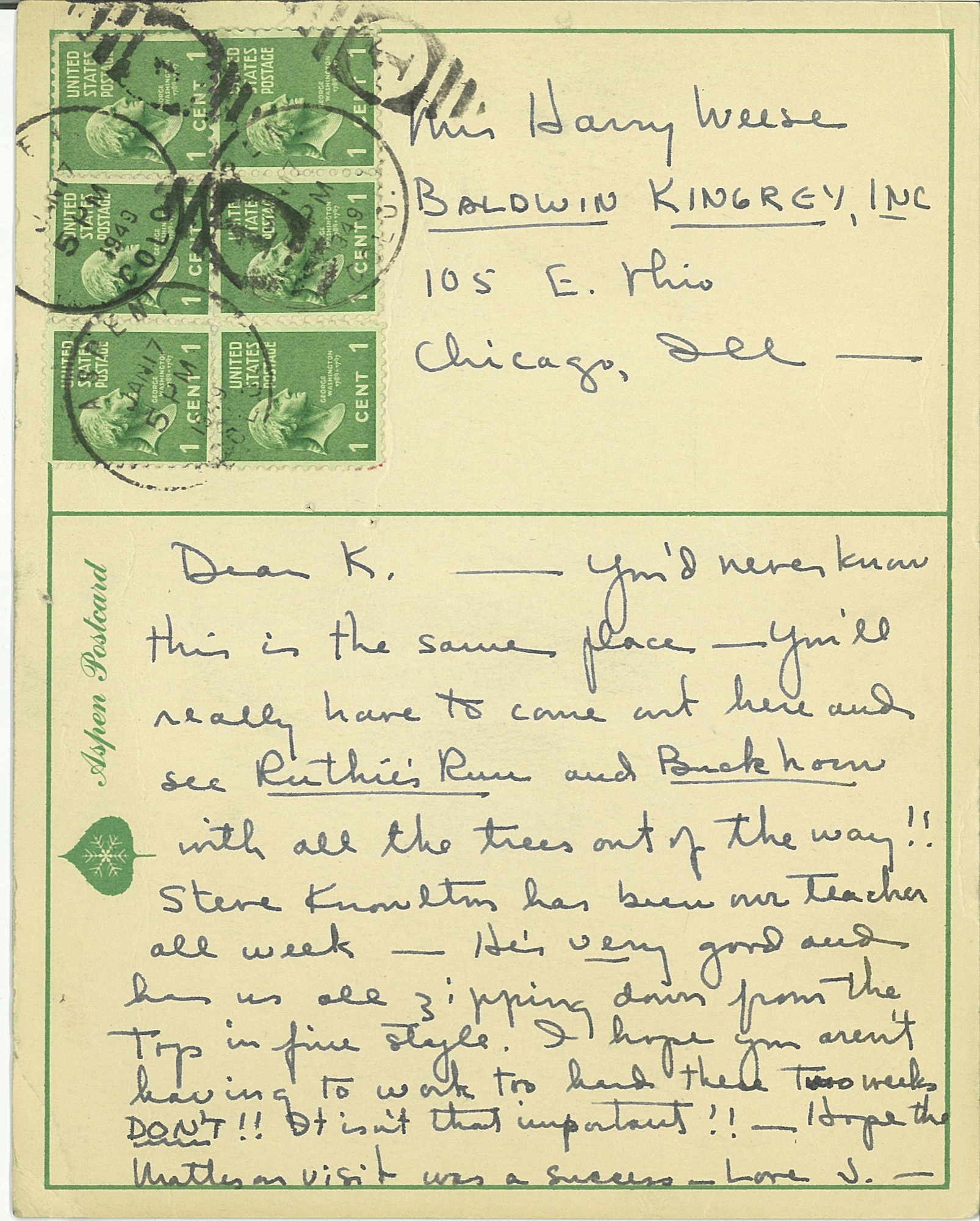

Baldwin Kingrey store in Chicago

In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father. While in the navy for three long years he kept a journal that he scratched in during calmer moments at sea. Here is an excerpt describing his vision for a retail store, entered on May 26, 1943,

“Thought of the (retail furnishings salon) shop for gathering together all beautiful and useful modern objects, which could be termed ‘furnishings’... Anonymous discoveries and subcontracted and assembled pieces of my design: foam and webbed couch in church pew form, telescoping coffee tables of magnesium or plastic, ... fabrics ... grass matting to a special design ... restaurant adjacent, movies, bar, a small haven for those interested ... a trip abroad to buy imports first thing after peace.” “In the early fifties, there was no modern anything to be found in the Midwest. So my mother with her partner Jody Kingrey opened a furniture store, prompted by my father.”

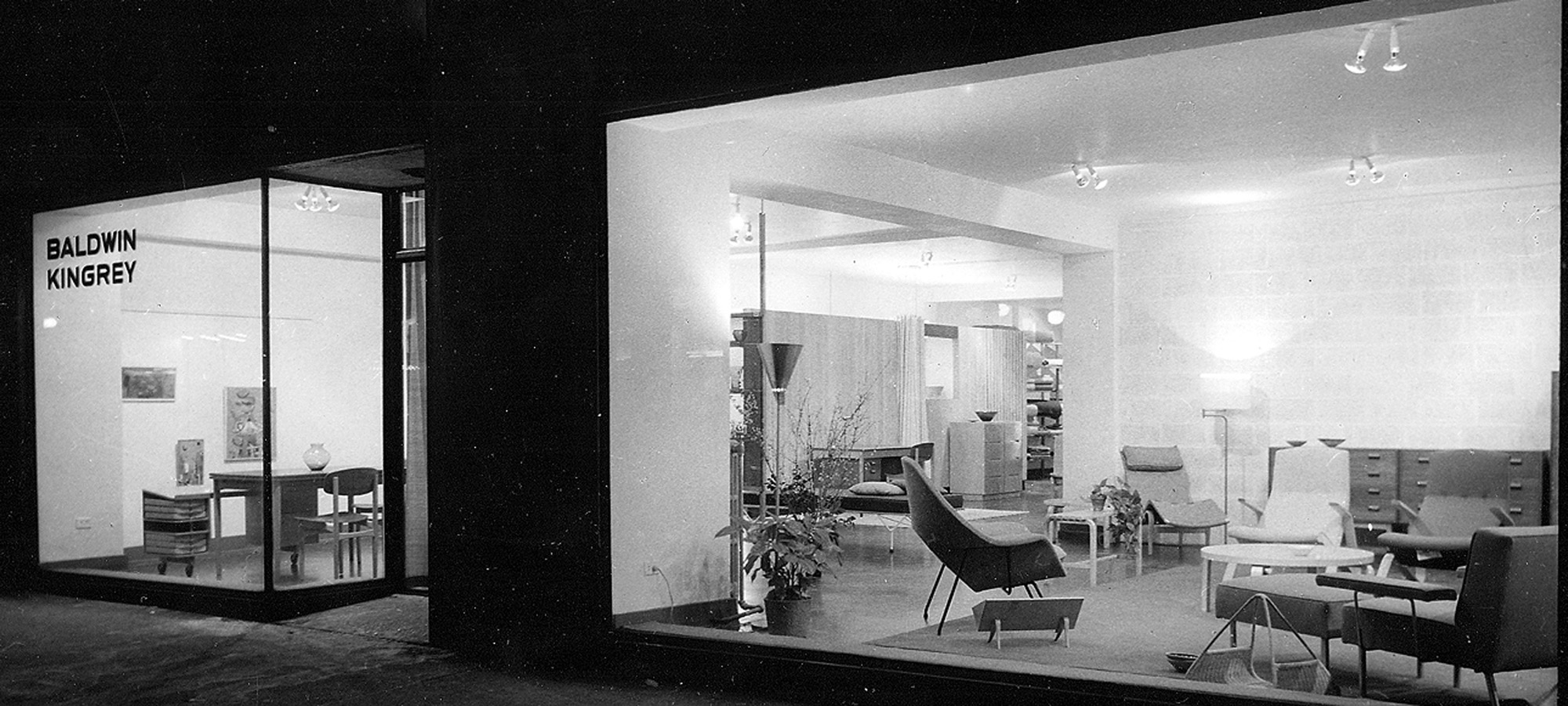

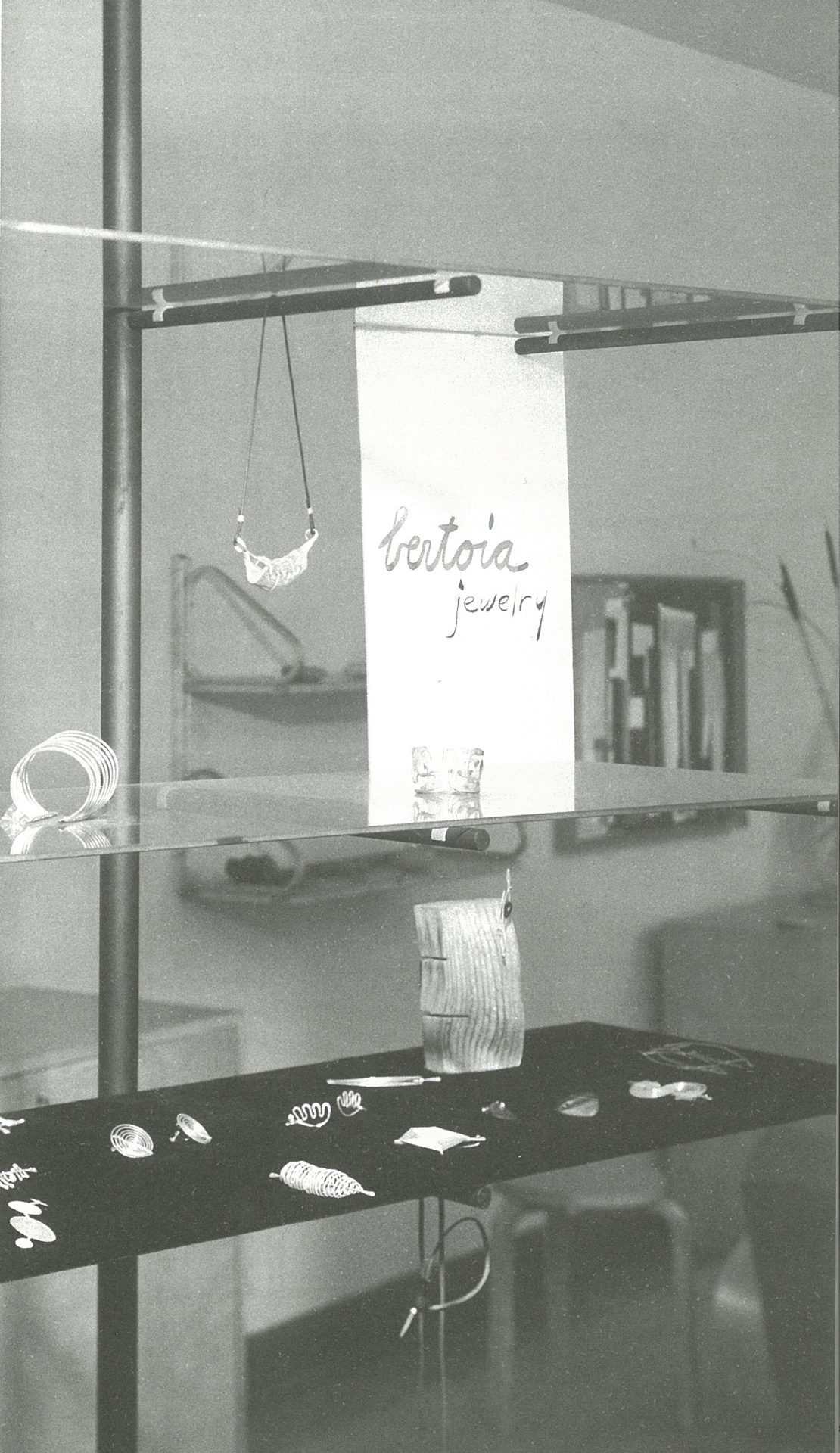

Wasting no time postwar, Dad got permission to handle the Midwestern franchise for Artek furniture from Scandinavia. Ben Baldwin designed fabrics and window displays. Harry Bertoia showed his jewelry, James Prestini sold his turned wooden bowls, artists queued up to exhibit in the space, and Baldwin Kingrey opened its doors to an eager audience hungry for modern design.

In words from John Brunetti, author of Baldwin Kingrey, Midcentury Modern in Chicago, 1947–1957,

“Baldwin Kingrey was more than a retail enterprise. It served as an informal gathering place for students and faculty from Chicago’s influential Institute of Design (ID) as well as the city’s architects and interior designers, who looked for inspiration from the store’s inventory of furniture by leading modernist designers such as Alvar Aalto, Bruno Mathsson, Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen.”

My father started his architectural practice at a drafting table in the back of the Baldwin Kingrey store. He did all the graphics for the store, designed a line of furniture and lighting he called BALDRY, designed open shelving of floating glass and steel poles to display Bertoia jewelry, Venini vases and “Chem Ware”—beakers and Petri dishes in simple, beautiful forms, that they found in the industrial section of the city. There was resourcefulness, an informality, and a frugality at play. In my mother’s words,

“Harry and I stopped at a place that sold Cadillacs on LaSalle Street. They were selling out their leather for automobiles, so we bought the whole batch. A lot of our furniture was covered in Cadillac leather! We were in a sense the precursor to Crate and Barrel. They came down to study us a lot. Carole Segal (founder of Crate and Barrel) was a friend of mine, and I gave her help. I gave her a lot of source material.”

As I was growing up, there was a steady stream of visitors, all immersed in modern design. My mother reminisced,

“You couldn’t travel across the country without changing planes or trains in Chicago. Everyone would stop in Chicago. The people that rushed into Baldwin Kingrey were mostly from the city and they didn’t have much money. Instead, they had some sort of new outlook—a vision. They loved the simplicity of our ‘plain’ furniture.”

The road was unpaved, the waters uncharted, the possibilities endless. Many would visit our house to exchange ideas, talk about projects, drink a cocktail or two, even draw at the dinner table. One of these more salient meetings I remember clearly:

I must have been ten or eleven when a distinguished elderly gentleman came to visit us in Barrington. My father was notably excited to share our modern house with him. When it was time to leave, he escorted him down the walkway under the grape arbor to his car with me trailing behind. As he drove off, my father turned to me with tears streaming and whispered, “There goes my mentor. There goes the most important man in my life.” This was none other than Alvar Aalto, who had been Dad’s professor and was a great influence on his architecture and design philosophy.

First pitstop in Aspen

When peace came in 1945, Dad stepped off his ship in San Francisco and he and Mom drove eastward. On their way back to Chicago, they stopped in Aspen and took some black-and-white photographs of downtown. The town consisted of several stone and brick buildings—the Courthouse, the Wheeler Opera House, the church and Hotel Jerome. All other structures were small Victorians, a few storefronts, dirt roads, and occasional wooden lean-tos that sheltered a few dozing horses. Many of the houses had been plunked on rubble walls to speed construction for miners and their families in the boom of the late 1800s. Builders often used pattern books with a 12/12 pitch for snow load, imparting a human scale that has long since been lost.

Dad—an avid skier—fell in love with Aspen and began a tradition of visiting each winter and summer that lasted throughout his life. Luckily, he included us in this adventure, and, thus, I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as “the town Chicago built.”

“I have precious memories of Aspen in those early days. It has been described as ‘the town Chicago built.’ ”

In the 1940s in Chicago, my parents were friends with Walter Paepcke, a successful industrialist, philanthropist, and president of the Container Corporation of America. It was Walter’s remarkable wife Elizabeth, a notable influence on Chicago’s cultural life and one of Mom’s favorite people, who exposed Walter to modern design and artistic sensibilities. In this spirit, Paepcke consulted with Walter Gropius, brought Laszlo Maholy-Nagy to the Institute of Design, befriended Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer, and photographer Ferenc (Franz) Berko, also at ID at the time. Mom and Dad intersected with ID, as the campus was a hub for young and ambitious modernists.

In a memoir, Elizabeth Paepcke describes her first impression of Aspen after skinning up the mountain in 1939,

“At the top, we halted in frozen admiration. In all that landscape of rock, snow and ice, there was neither print of animal nor track of man. We were alone as though the world had just been created and we its first inhabitants.”

Walter Paepcke first visited Aspen in the spring of 1945 urged by Elizabeth. To him, this seemed the idyllic place to implement a new Chautauqua. The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, “for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.” Thus the Aspen Institute of Humanistic Studies was born. Herbert Bayer was brought in to oversee the design of the campus, and Franz Berko became the Institute’s in-house photographer. The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.

“The Aspen idea was to create a place, in Walter’s words, ‘for man’s complete life ... where he can profit by healthy, physical recreation, with facilities at hand for his enjoyment of art, music, and education.’ ”

“The pull to Aspen was magnetic, and as many of Chicago’s design elite began to relocate and vacation there, my parents were among them.”

There was a palpable charm to Aspen in the fifties and sixties, which I feel so fortunate to have experienced first hand. Many Europeans returned to the town to settle after serving in the famed 10th Mountain Division during the war. Their training camp, Camp Hale, was nearby and enlisted men would often ski Aspen on the weekends. Friedl Pfeifer was one who started the Aspen Ski School; Fritz Benedict set up an architectural practice. After the war, many of these veterans taught skiing in winter and worked as carpenters in summer. Their wives typically ran the shops, bakeries, and clothing stores in town. Franz Berko stayed, continued his photographic career, and raised his family. His wife Mirte ran a toy shop that sold wooden toys from Europe. Herbert Bayer designed the early buildings at the Aspen Institute and settled in town with his wife Joella. Fritz Benedict, the noted local architect, married Joella’s sister Fabi, and he began developing Aspen. Joella and Fabi shared a famous mother—the poet Mina Loy. This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its “quiet years.” My parents were in the midst of the action.

“This was an illustrious and hearty group of early modernist settlers who loved the mountains and skiing and who brought Aspen out of its ‘quiet years.’ ”

Christmases at the Hotel Jerome

Nora Berko, daughter of Franz and Mirte, remembers visiting us at the Hotel Jerome every Christmas. We always stayed in the southeast corner with full view through the Victorian lace curtains of Main Street and Ajax Mountain. As our collective parents went out to dinner and dancing, usually at the Red Onion, we had full run of the rickety hotel, much like Eloise at the Plaza. With its worn and dusty velvet furniture, Victorian floral wallpaper, and black-and-white photos of skiers sporting the reverse shoulder stance and the latest style of stretch pants, it was a far cry from our modern and minimal environment at home. We ran up and down the creaking stairs and played in the elevator—a novelty—as it was the only one in town. The rooms cost ten dollars per night, radiators clanked, and in some seasons ropes were ceremoniously draped across the room sinks warning of giardia in the water. But we loved the Jerome. It felt like an old comfortable shoe. The Paepckes leased the hotel as well as the Opera House so Elizabeth had license to paint the exterior white with light blue arches over the windows. The hotel looked like a grand Bavarian wedding cake in a perpetual wink; an impressive structure always easy to spot for a youngster finding her way home after ski school. It stayed this way for several decades.

Every Christmas we walked through snowy streets to the Berko’s for Christmas dinner. Their house was a modestly scaled and cozy Victorian in Aspen’s west end. Real candles burned on the Christmas tree, which was festooned with wooden ornaments from Mirte’s toy shop. Marzipan treats imported from Europe were served. There was no central heat. Brrrr. But for a young girl, I was sure that I was encompassed within a magical snow globe.

Aspen became our second home

In the late sixties, my mother bought a small Victorian in Aspen's west end for a mere pittance. We began to spend summers in the mountains, which was a blessed relief from the mugginess of the Midwest. My father worked on projects in and around Aspen. Many went unbuilt but some were realized, including the Given Institute. He had a plan for a new airport, and he wanted to bring light rail from Glenwood to Aspen to alleviate vehicular traffic. Always drawing, usually at the kitchen table, I rarely saw him without a pencil in hand. In 1969 Charles Moore (who taught at Yale), and Fritz Benedict lured a class of Yale architectural grad students to spend a summer in the nearby mountains and build experimental projects. When these young, handsome students appeared, they were eager to rub shoulders with my father at his kitchen table. (A few rubbed shoulders with his daughters as well!) One of these architects, Harry Teague, arrived and never left. Over four decades, he has made a significant imprint on the town, designing notable residences and many of Aspen’s most prestigious cultural buildings, including Harris Hall, the Aspen Music School campus, and the Aspen Center For Physics. He has become one of Aspen’s “own” by championing a humanist aesthetic that continues to raise the bar of modern architecture in the Roaring Fork Valley.

Aspen today

Though old Aspen is rapidly fading, thank goodness there are offspring. I am currently collaborating with Teague on a family compound for Nora Berko and her family that incorporates her father’s studio, now designated historic. Her daughter Mirte has dedicated much time and effort organizing her grandfather’s impressive archives of photographs for us to appreciate into perpetuity. The Aspen Institute carries on robustly while continuing to pay homage to its early founders and players. △

Read "Growing Up Weese" to find out what artist and designer Marcia Weese is up to today.

Seduction Design

Former Eames art director and CommArts co-founder Richard Foy muses on the bowerbird’s incredible construction and composition skills and human design

Design is everywhere. People have always valued design expertise, even dating back millions of years to the first tools ever used and now recently unearthed. From the harnessing of fire, clubbing of opponents, carrying water in vessels, throwing spears, and using fur blankets, to riding around in Teslas, we like and rely on design.

Daily design

Today, most everything we have, use, want, and need is designed. We have even designed robotics and programs that design things for us. Every time we dress ourselves, email, make a meal, buy things, plant gardens, do a spreadsheet, we become designers. We are making functional decisions based on what we need, what it says, and how it feels. We are reflecting ourselves and how we want to be perceived through our choices. We are designing. We do this daily for work, pleasure, and living, without pause or conscious thought.

Design is intrinsic to art, invention, and creativity. Design is different from art because it tends to focus on underlying structure, function, or purpose more than personal expression—although the best designs have or tell a story that expresses a point of view. We rely on design for practical solutions to everyday problems or issues. A lot of design is offered as a service to help people, businesses, and institutions.

Design and cultural creativity advance humanity

The professional practice of design creates solutions and makes the places, products, and market of the future. We value communities where there is a high level of design and cultural creativity that responsibly advances society. Florence emerged during the Renaissance because of its design and art contributions, which we still value 500-plus years later. Humanity, backed by theology claims dominion over all species. From the human (not particularly Biblical) view it’s based on our historically unmatched and singular ability to design, make, and use tools.

Amorous architecture

A newly recognized and different breed of designer is practicing in Australia and New Guinea. They have gained notoriety by becoming experts on the art of seduction. Their primary design passion is the field of amorous architecture, interiors, landscaping, and the courtship arts of song and dance. The places they build attract, entertain, charm, and seduce females. They are among the best in that business and are studied and respected worldwide for their thorough design approach, execution, and resulting social benefits. They have perfected their skills over thousands of years, which further attests to their expertise and effectiveness.

"Their primary design passion is the field of amorous architecture, interiors, landscaping..."

Attraction by design

Creative human designers like to wear black clothing. These designers prefer feathers, as all are members of the bowerbird family. Their closest kin on this continent are ravens and crows. Some bowerbirds are a bit larger and live a little longer, up to twenty-seven years.

Another consideration before comparing bird designers to human designers is the possibility that their design creativity may emanate from the same source. Design as a noun identifies something intentionally made or resulting from an idea or plan. Design as a verb is an act or the process of making, visualizing, creating, or turning an idea into a new reality.

The design process, whether painstakingly thoughtful or impulsively spontaneous follows a pattern. Stasis, curiosity, imagination, question, attempt, failure, learning, success, change. Change as a causal dynamic is as present in the space, time, matter, and energy of the cosmos as it is in the buzzing subatomic and atomic particles of our biological cells. The question is what or where is the intention responsible for the nonhuman-made, natural world?

Source and cause of design

There is a Zen koan that says, “Learn to listen to the wisdom inside of a rock.” Are humans and other biological creatures all part of the same dynamic forces responsible for change? Are we all variants of the same energy that cannot be created (designed) or destroyed but only transformed? Is change the cause not just the result of creative design? Does the bowerbird follow the same design impulse as do humans? Our link may be that we were all designed by the same cauldron of the cosmos 13.8 billion years ago. We are the same stardust particles that were floating around then but reconstituted by evolution, physics, gravity, thermodynamics, and chemistry. Maybe bowerbirds, rocks, and everything is caused by constant flux of creative change, at one with the universe.

"Maybe bowerbirds, rocks, and everything is caused by constant flux of creative change, at one with the universe."

Male bowerbirds are renowned for designing painstakingly ornate, complex, and personalized bachelor pads and performance routines to attract females for amorous encounters. A female bowerbird requires and insists on unlimited choice and opportunity to select her mate based solely on her assessment of how well the male earns her trust and displays his creative intelligence. The stakes are high. Seventy-five percent of females in one study area visited only the one same bower out of dozens of offerings before mating.

Older, more experienced males will succeed with dozens of females in a single breeding season while younger males will seduce only a single one of his dozens of visitors. A lot rides on the design quality of the bower; its form, color, and execution, followed by a concert and dance performance. Providing a sense of comfort in combination with self control, respect, and restraint gains reproduction rights that help determine the survival of their species. Everything is designed for the pleasure of the female and winning her mate-selection preference.

Bower architecture

A bower is defined as a secluded place, often in a garden, enclosed by foliage or an arbor. It can also be a summer house or garden cottage, an inner room, or a boudoir. Lovely.

Males build three types of bowers: “maypoles,” “mats,” and “avenues.” “Maypoles” can be single- or double-masted towers. Some are built around a young sapling that becomes its centerpiece. Others have curved walls that frame and showcase the awaiting male. They are dotted with colors that help their visibility and location of the bower below. Sometimes a roof is designed immediately below the tower, which provides shade or privacy in the bower. Towers stand out from the brush and call attention through their distinctive forms.

“Mats” are landing pads made from collected plant materials such a fresh green moss that has been carefully laid and ringed with individually selected and arranged ornaments; making, if you like, the equivalent of an oriental rug. It may contain fresh leaves, petals, owers, snail shells, bits of foil, candy wrappers, pebbles, glass shards, fruit, colored plastic utensils, bottle caps, can pull-tabs, all of the same color or predetermined mix of colors. One researcher found a glass eye in a bower, undoubtedly a very distinctive and intentional treasure piece ripe with symbolism.

“Avenues” are longer and narrower mats that seem to function as landing strips; again, they are ornately marked with color-coordinated found objects. Airport towers, landing pads, and runways would be the human architectural equivalents.

All three schemes sport specific colors that may be a single dominant color or an arrangement composed of multiple colors. Blue seems popular as evident when searching Google images. All are designed to be spotted from the air by mate-seeking females. These are not unlike the bright signs at Saturday night social gathering places and night clubs.

The colors of decorative elements that males choose for their bowers match the preferences of females. Male bowerbirds play to their audience and design for their market segment and demographics. Bowerbird species that build the most elaborate bowers are dull in color, whereas the males of species with less elaborate bowers have brighter plumage.

"The colors of decorative elements that males choose for their bowers match the preferences of females."

The design critics

Males are assessed based on the quality of their bower construction. Males with quality displays achieve mating success, suggesting that females gain important benefits from mate choice. Bowerbird ornamentation is perceived as a sexual indicator of general health, intelligence, and disease-resistant heritage.

The various twig fences, arching walls, roofs, and decorations get painted or stained by colors made by chewing plants and adding charcoal with saliva. Lastly, objects are sometimes arranged by size, large to small, that create a false perspective to hold attention and gain the advantage of more time spent. Perspective also makes the awaiting male appear to be a bigger and better mate.

Females search for mates by visiting multiple bowers, returning multiple times, watching his elaborate courtship displays, inspecting the quality, and tasting the paint the male has made and placed on the bower walls. Many females choose the same male, and many underwhelming males go without mates. Females choosing top-mating males tend to return next year and search less.

Bowers take weeks to design and build, are constantly refreshed, and their color elements are rearranged with bright, shiny ones. Males will also do recon flights to inspect their competition and steal whatever bauble would make their bower more attractive.

Showtime

Once the stage has been set and a visitor lands nearby, it's showtime. These Justin Timberlake males must know how to dance and sing in order to seal the deal. Male bowerbirds are superb vocal mimes. They have been known to imitate pigs, waterfalls, and human chatter. Some bowerbirds mimic other local bird species as part of their own concert. Then the male has to strut his stuff, and strike outlandish poses while dancing and singing to lure his guest into the bower.

A female chooses to visit only bowers that appeal to her. She will land close but far enough to avoid feeling threatened. When she comes closer and stops she may allow the male to approach and mate. A too-eager male will fail. Males only succeed when the visiting female feels comfortable and protected from more aggressive males.

Imagine if every human male had to individually design his architecture, build it alone, lay out a garden, design the interiors, furnish it, paint it, maintain it, sing, dance, and strike poses, or he wouldn’t even get a date!

The social implications of the bowerbird species have always been based on consideration of the female societal role. Only in the last few decades have some western societies realized the importance and significance of women to civilization. Today, there are more women on the planet, more women in the workforce, and in the educational system attaining higher academics than men. CEOs estimate that 80 to 95 percent of all consumer spending is determined by women—homes and their locations, insurance, appliances, furnishing, food, clothing, schools, and even tools.

Bowerbirds seem to have long designed for a sociology that has always given females due respect, something that has taken far longer in human societies.

“Bowerbirds seem to have long designed for a sociology that has always given females due respect, something that has taken far longer in human societies.”

The bowerbird model is a classic lesson on how successful design is doing the best you can, with what you’ve got, in terms of what social values you encourage through design.

Richard Foy, former art director for Charles and Ray Eames and founding partner of CommArts design firm, has designed many brand identities and places worldwide, including Madison Square Garden (New York City), O2 Dome (London, UK), Pearl Street Mall (Boulder, Colorado), LA Live (Los Angeles, California), and the branding for Spyder Sportswear, and Star Trek — The Motion Picture.